Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Food and Personal Care Products—What Do We Know about Their Safety?

Abstract

1. Introduction

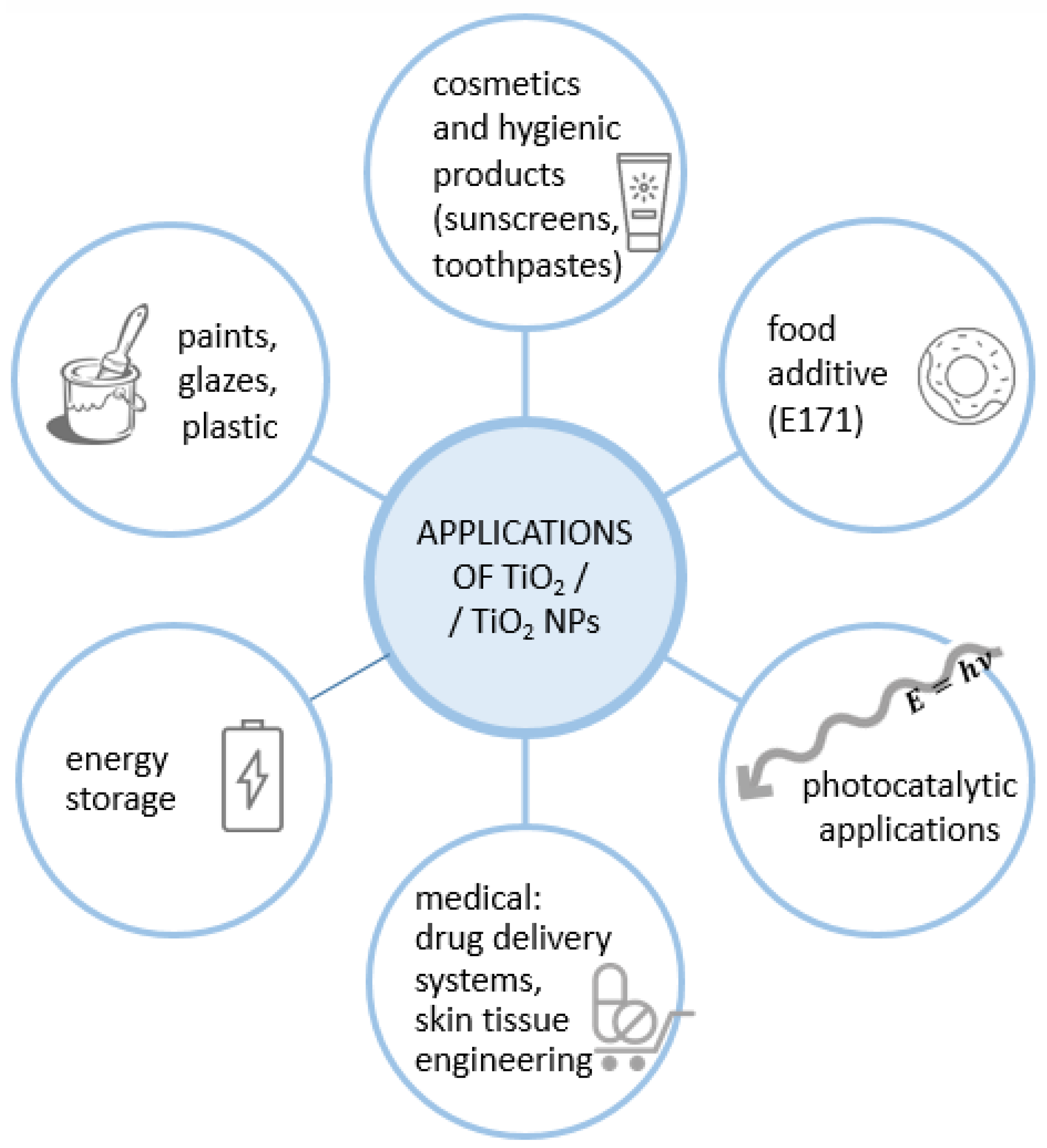

1.1. Properties and Applications of Titanium Dioxide

1.2. Effect of TiO2 NPs Shape on Their Toxicity

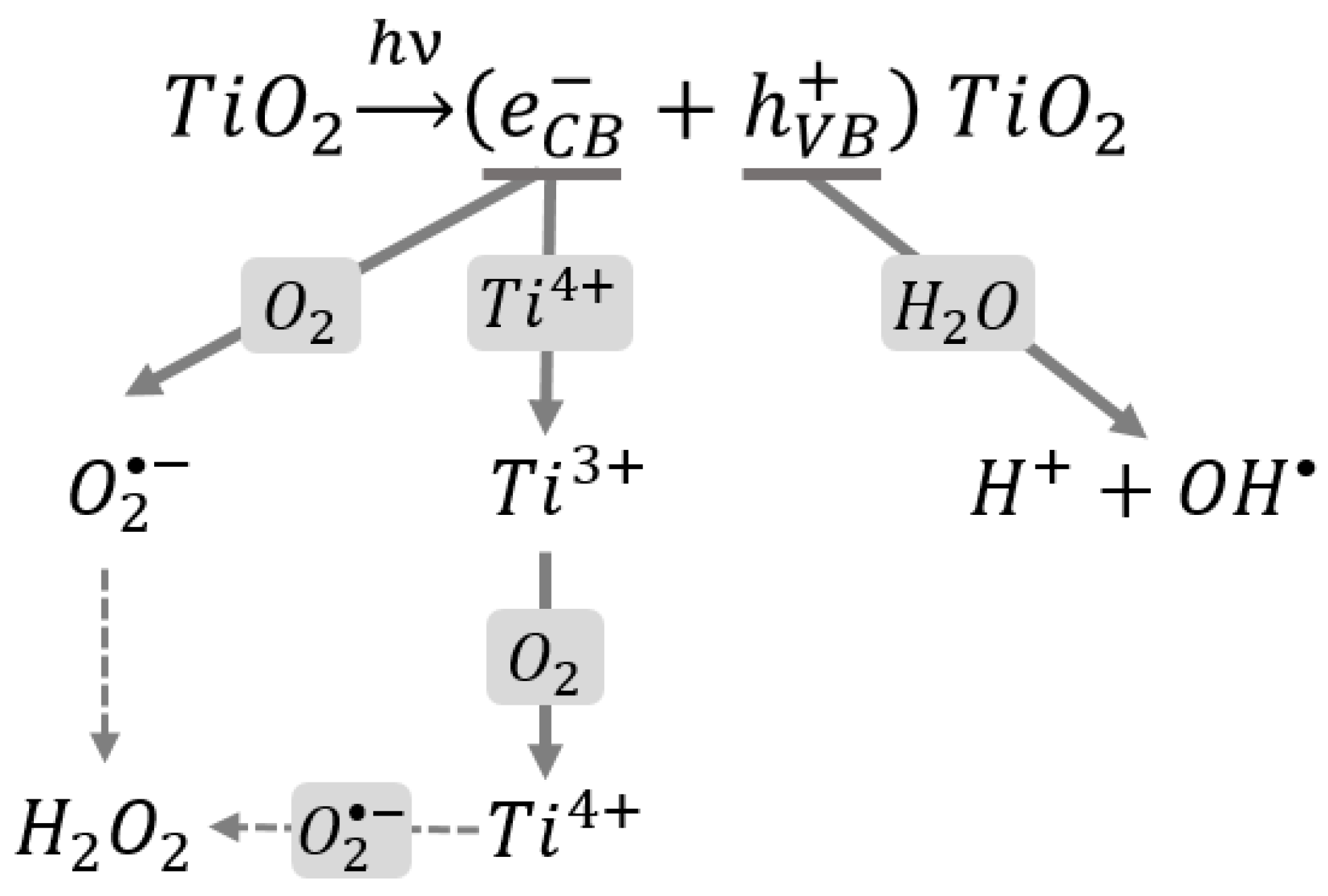

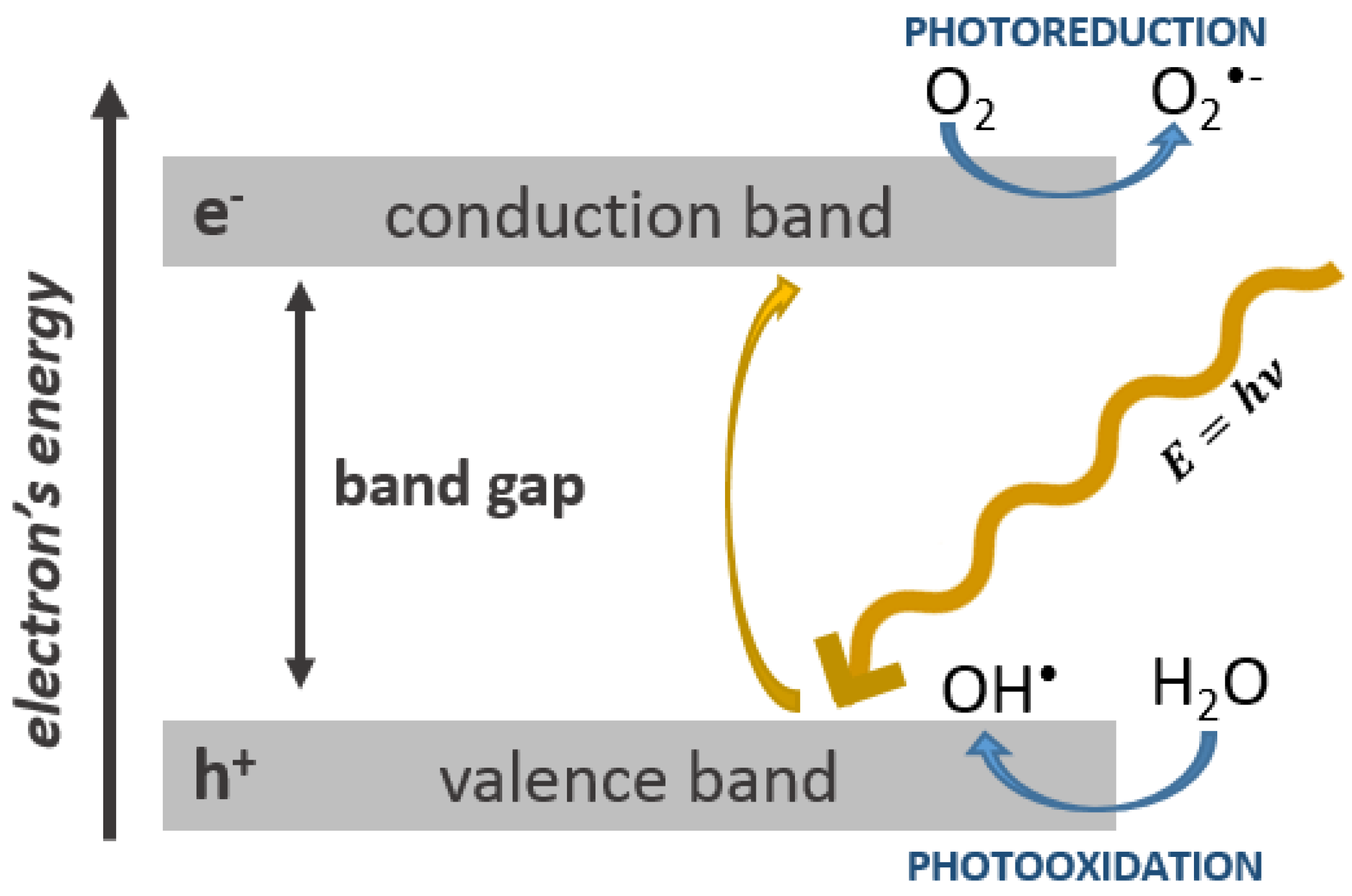

1.3. The Role of Oxidative Stress in the Toxicity of Nanoparticles

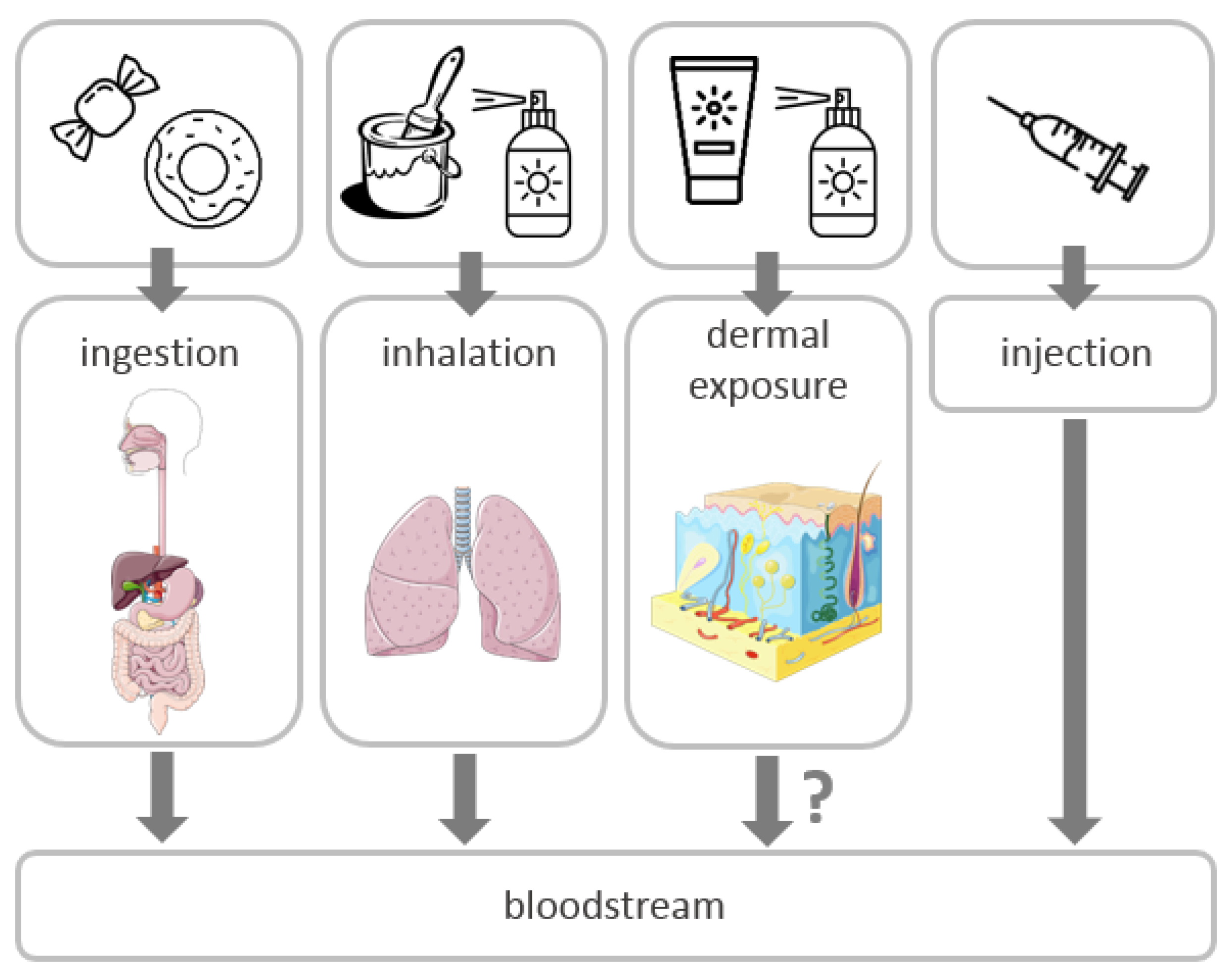

2. Routes of Exposure and Toxicity of TiO2 NPs

2.1. Ingestion—TiO2 NPs as a Food Additive (E171)

2.2. Local Effects of Tio2 NPs on the Intestinal Barrier and Changes in the Gut Microbiota

2.3. Dermal Exposure—TiO2 NPs as a Sunscreen Compound

3. ’Green’ TiO2 NPs—Safer Perspective for the Future?

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IARC. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Carbon Black, Titanium Dioxide, and Talc; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2010; Volume 93, ISBN 978-92-832-1293-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, T.D.; Matos, G.R. Titanium dioxide end-use statistics, 1975-2004. In Historical Statistics for Mineral and Material Commodities in the United States; Data Series 140; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, T.; Wang, Y. Insights into TiO2 polymorphs: Highly selective synthesis, phase transition, and their polymorph-dependent properties. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 52755–52761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smijs, T.G.; Pavel, S. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: Focus on their safety and effectiveness. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2011, 4, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccinno, F.; Gottschalk, F.; Seeger, S.; Nowack, B. Industrial production quantities and uses of ten engineered nanomaterials in Europe and the world. J. Nanopart. Res. 2012, 14, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, A.; Westerhoff, P.; Fabricius, L.; von Goetz, N. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles in food and personal care products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 2242–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziental, D.; Czarczynska-Goslinska, B.; Mlynarczyk, D.T.; Glowacka-Sobotta, A.; Stanisz, B.; Goslinski, T.; Sobotta, L. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles: Prospects and applications in medicine. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, J.-Y.; Li, H.-Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, A.Z.-J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.-Q.; Sun, H.-T.; Al-Deyab, S.S.; Lai, Y.-K. TiO2 nanotube platforms for smart drug delivery: A review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 4819–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babitha, S.; Korrapati, P.S. Biodegradable zein-polydopamine polymeric scaffold impregnated with TiO2 nanoparticles for skin tissue engineering. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 12, 055008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, M.S.; Nica, I.C.; Dinischiotu, A.; Varzaru, E.; Iordache, O.G.; Dumitrescu, I.; Popa, M.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Pircalabioru, G.G.; Lazar, V.; et al. Photocatalytic, antimicrobial and biocompatibility features of cotton knit coated with Fe-N-Doped titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Materials 2016, 9, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seisenbaeva, G.A.; Fromell, K.; Vinogradov, V.V.; Terekhov, A.N.; Pakhomov, A.V.; Nilsson, B.; Ekdahl, K.N.; Vinogradov, V.V.; Kessler, V.G. Dispersion of TiO2 nanoparticles improves burn wound healing and tissue regeneration through specific interaction with blood serum proteins. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Kim, M.G.; Lee, J.Y.; Cho, J. Green energy storage materials: Nanostructured TiO2 and Sn-based anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Envron. Sci. 2009, 2, 818–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, R.K.; Gaur, K.; Cátala Torres, J.F.; Loza-Rosas, S.A.; Torres, A.; Saxena, M.; Julin, M.; Tinoco, A.D. Fueling a hot debate on the application of TiO2 nanoparticles in sunscreen. Materials 2019, 12, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aillon, K.L.; Xie, Y.; El-Gendy, N.; Berkland, C.J.; Forrest, M.L. Effects of nanomaterial physicochemical properties on in vivo toxicity. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanone, S.; Boczkowski, J. Biomedical applications and potential health risks of nanomaterials: Molecular mechanisms. Curr. Mol. Med. 2006, 6, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merisko-Liversidge, E.M.; Liversidge, G.G. Drug nanoparticles: Formulating poorly water-soluble compounds. Toxicol. Pathol. 2008, 36, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.-S.; Kang, B.-C.; Lee, J.K.; Jeong, J.; Che, J.-H.; Seok, S.H. Comparative absorption, distribution, and excretion of titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles after repeated oral administration. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2013, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koltermann-Jülly, J.; Keller, J.G.; Vennemann, A.; Werle, K.; Müller, P.; Ma-Hock, L.; Landsiedel, R.; Wiemann, M.; Wohlleben, W. Abiotic dissolution rates of 24 (nano) forms of 6 substances compared to macrophage-assisted dissolution and in vivo pulmonary clearance: Grouping by biodissolution and transformation. NanoImpact 2018, 12, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, E.; Barreau, F.; Veronesi, G.; Fayard, B.; Sorieul, S.; Chanéac, C.; Carapito, C.; Rabilloud, T.; Mabondzo, A.; Herlin-Boime, N.; et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle impact and translocation through ex vivo, in vivo and in vitro gut epithelia. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2014, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.G.; Peijnenburg, W.; Werle, K.; Landsiedel, R.; Wohlleben, W. Understanding dissolution rates via continuous flow systems with physiologically relevant metal ion saturation in lysosome. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurr, J.-R.; Wang, A.S.S.; Chen, C.-H.; Jan, K.-Y. Ultrafine titanium dioxide particles in the absence of photoactivation can induce oxidative damage to human bronchial epithelial cells. Toxicology 2005, 213, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, A. Toxic potential of materials at the nanolevel. Science 2006, 311, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroozandeh, P.; Aziz, A.A. Merging worlds of nanomaterials and biological environment: Factors governing protein corona formation on nanoparticles and its biological consequences. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saptarshi, S.R.; Duschl, A.; Lopata, A.L. Interaction of nanoparticles with proteins: Relation to bio-reactivity of the nanoparticle. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2013, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetwynd, A.J.; Zhang, W.; Thorn, J.A.; Lynch, I.; Ramautar, R. The nanomaterial metabolite corona determined using a quantitative metabolomics approach: A pilot study. Small 2020, 2000295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.O.; Di Maio, A.; Guggenheim, E.J.; Chetwynd, A.J.; Pencross, D.; Tang, S.; Belinga-Desaunay, M.-F.A.; Thomas, S.G.; Rappoport, J.Z.; Lynch, I. Surface chemistry-dependent evolution of the nanomaterial corona on TiO2 nanomaterials following uptake and sub-cellular localization. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegri, M.; Bianchi, M.G.; Chiu, M.; Varet, J.; Costa, A.L.; Ortelli, S.; Blosi, M.; Bussolati, O.; Poland, C.A.; Bergamaschi, E. Shape-related toxicity of titanium dioxide nanofibres. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, D.W.; Wu, N.; Hubbs, A.F.; Mercer, R.R.; Funk, K.; Meng, F.; Li, J.; Wolfarth, M.G.; Battelli, L.; Friend, S.; et al. Differential mouse pulmonary dose and time course responses to titanium dioxide nanospheres and nanobelts. Toxicol. Sci. 2013, 131, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.M.; Teesy, C.; Franzi, L.; Weir, A.; Westerhoff, P.; Evans, J.E.; Pinkerton, K.E. Biological response to nano-scale titanium dioxide (TiO2): Role of particle dose, shape, and retention. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2013, 76, 953–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, P.H.; Knudsen, K.B.; Štrancar, J.; Umek, P.; Koklič, T.; Garvas, M.; Vanhala, E.; Savukoski, S.; Ding, Y.; Madsen, A.M.; et al. Effects of physicochemical properties of TiO2 nanomaterials for pulmonary inflammation, acute phase response and alveolar proteinosis in intratracheally exposed mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2020, 386, 114830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, A.-L.; Dumont, L.; Vandroux, D.; Millot, N. Titanate nanotubes: Towards a novel and safer nanovector for cardiomyocytes. Nanotoxicology 2013, 7, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea, M.; Bonetta, S.; Iannarelli, L.; Giovannozzi, A.M.; Maurino, V.; Bonetta, S.; Hodoroaba, V.-D.; Armato, C.; Rossi, A.M.; Schilirò, T. Shape-engineered titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NPs): Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity in bronchial epithelial cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 127, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, T.; Papp, A.; Igaz, N.; Kovács, D.; Kozma, G.; Trenka, V.; Tiszlavicz, L.; Rázga, Z.; Kónya, Z.; Kiricsi, M.; et al. Pulmonary impact of titanium dioxide nanorods: Examination of nanorod-exposed rat lungs and human alveolar cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 7061–7077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Saez, G.; Muggiolu, G.; Lavenas, M.; Le Trequesser, Q.; Michelet, C.; Devès, G.; Barberet, P.; Chevet, E.; Dupuy, D.; et al. In situ quantification of diverse titanium dioxide nanoparticles unveils selective endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent toxicity. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brezová, V.; Gabčová, S.; Dvoranová, D.; Staško, A. Reactive oxygen species produced upon photoexcitation of sunscreens containing titanium dioxide (an EPR study). J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2005, 79, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdörster, G.; Oberdörster, E.; Oberdörster, J. Nanotoxicology: An emerging discipline evolving from studies of ultrafine particles. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCord, J.M. The evolution of free radicals and oxidative stress. Am. J. Med. 2000, 108, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skocaj, M.; Filipic, M.; Petkovic, J.; Novak, S. Titanium dioxide in our everyday life; Is it safe? Radiol. Oncol. 2011, 45, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeel, M.; Jabeen, F.; Shabbir, S.; Asghar, M.S.; Khan, M.S.; Chaudhry, A.S. Toxicity of nano-titanium dioxide (TiO2-NP) through various routes of exposure: A review. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 2016, 172, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, B. Critical review of public health regulations of titanium dioxide, a human food additive. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2015, 11, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudefoi, W.; Terrisse, H.; Popa, A.F.; Gautron, E.; Humbert, B.; Ropers, M.-H. Evaluation of the content of TiO2 nanoparticles in the coatings of chewing gums. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2018, 35, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiss, O.; Ponti, J.; Senaldi, C.; Bianchi, I.; Mehn, D.; Barrero, J.; Gilliland, D.; Matissek, R.; Anklam, E. Characterisation of food grade titania with respect to nanoparticle content in pristine additives and in their related food products. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2020, 37, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA-European Food Safety Authority. Re-evaluation of titanium dioxide (E 171) as a food additive. EFSA J. 2016, 14, e04545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettini, S.; Boutet-Robinet, E.; Cartier, C.; Coméra, C.; Gaultier, E.; Dupuy, J.; Naud, N.; Taché, S.; Grysan, P.; Reguer, S.; et al. Food-grade TiO2 impairs intestinal and systemic immune homeostasis, initiates preneoplastic lesions and promotes aberrant crypt development in the rat colon. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire de l’Alimentation, de l’Environnement et du Travail (ANSES). Avis Relatif à Une Demande d’Avis Relatif à l’Exposition Alimentaire Aux Nanoparticules de Dioxyde de Titane; ANSES: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arrêté du 17 avril 2019 Portant Suspension de la Mise sur le Marché des Denrées Contenant l’Additif E 171 (dioxyde de titane-TiO2). Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000038410047&categorieLien=id (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Proquin, H.; Rodríguez-Ibarra, C.; Moonen, C.G.J.; Urrutia Ortega, I.M.; Briedé, J.J.; de Kok, T.M.; van Loveren, H.; Chirino, Y.I. Titanium dioxide food additive (E171) induces ROS formation and genotoxicity: Contribution of micro and nano-sized fractions. Mutagenesis 2016, 32, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grissa, I.; Elghoul, J.; Ezzi, L.; Chakroun, S.; Kerkeni, E.; Hassine, M.; El Mir, L.; Mehdi, M.; Ben Cheikh, H.; Haouas, Z. Anemia and genotoxicity induced by sub-chronic intragastric treatment of rats with titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2015, 794, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talamini, L.; Gimondi, S.; Violatto, M.B.; Fiordaliso, F.; Pedica, F.; Tran, N.L.; Sitia, G.; Aureli, F.; Raggi, A.; Nelissen, I.; et al. Repeated administration of the food additive E171 to mice results in accumulation in intestine and liver and promotes an inflammatory status. Nanotoxicology 2019, 13, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottola, F.; Iovine, C.; Santonastaso, M.; Romeo, M.L.; Pacifico, S.; Cobellis, L.; Rocco, L. NPs-TiO2 and lincomycin coexposure induces DNA damage in cultured human amniotic cells. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed-Talebi, S.M.; Kazeminezhad, I.; Motamedi, H. TiO2 hollow spheres as a novel antibiotic carrier for the direct delivery of gentamicin. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 13457–13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.C.; Sheskey, P.J.; Quinn, M.E. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients, 6th ed.; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-85369-792-3. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Patel, P.; Bakshi, S.R. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles: An in vitro study of DNA binding, chromosome aberration assay, and comet assay. Cytotechnology 2017, 69, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriere, M.; Arnal, M.-E.; Douki, T. TiO2 genotoxicity: An update of the results published over the last six years. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagenesis 2020, 503198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Peng, W.; Wang, W.; Feng, S. The size-dependent genotoxic potentials of titanium dioxide nanoparticles to endothelial cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2019, 34, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonastaso, M.; Mottola, F.; Colacurci, N.; Iovine, C.; Pacifico, S.; Cammarota, M.; Cesaroni, F.; Rocco, L. In vitro genotoxic effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (n-TiO2) in human sperm cells. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2019, 86, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Magaye, R.; Castranova, V.; Zhao, J. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles: A review of current toxicological data. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2013, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zijno, A.; De Angelis, I.; De Berardis, B.; Andreoli, C.; Russo, M.T.; Pietraforte, D.; Scorza, G.; Degan, P.; Ponti, J.; Rossi, F.; et al. Different mechanisms are involved in oxidative DNA damage and genotoxicity induction by ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles in human colon carcinoma cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2015, 29, 1503–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Yan, J.; Li, Y. Genotoxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. J. Food Drug Anal. 2014, 22, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agir pour l’Environnement. Rapport d’Enquête Sur la Présence de Dioxyde de Titane Dans les Dentifrices; Agir pour l’Environnement: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Streit um Weißmacher -Plusminus -ARD |Das Erste. Available online: https://www.daserste.de/information/wirtschaft-boerse/plusminus/sendung/hr/streit-um-titandioxid-100.html (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Bianchi, M.G.; Allegri, M.; Chiu, M.; Costa, A.L.; Blosi, M.; Ortelli, S.; Bussolati, O.; Bergamaschi, E. Lipopolysaccharide adsorbed to the bio-corona of TiO2 nanoparticles powerfully activates selected pro-inflammatory transduction pathways. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, R.; Nguyen, L.T.H.; Chiew, P.; Wang, Z.M.; Ng, K.W. Comparative differences in the behavior of TiO2 and SiO2 food additives in food ingredient solutions. J. Nanopart. Res. 2018, 20, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Doudrick, K. Emerging investigator series: Protein adsorption and transformation on catalytic and food-grade TiO2 nanoparticles in the presence of dissolved organic carbon. Environ. Sci. Nano 2019, 6, 1688–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Han, Y.; Li, F.; Li, Z.; McClements, D.J.; He, L.; Decker, E.A.; Xing, B.; Xiao, H. Impact of protein-nanoparticle interactions on gastrointestinal fate of ingested nanoparticles: Not just simple protein corona effects. NanoImpact 2019, 13, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, M.C.; Costa, C.; Silva, S.; Costa, S.; Dhawan, A.; Oliveira, P.A.; Teixeira, J.P. Effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in human gastric epithelial cells in vitro. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2014, 68, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia-Ortega, I.M.; Garduño-Balderas, L.G.; Delgado-Buenrostro, N.L.; Freyre-Fonseca, V.; Flores-Flores, J.O.; González-Robles, A.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Hernández-Pando, R.; Rodríguez-Sosa, M.; León-Cabrera, S.; et al. Food-grade titanium dioxide exposure exacerbates tumor formation in colitis associated cancer model. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 93, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, P.A.; Morón, B.; Becker, H.M.; Lang, S.; Atrott, K.; Spalinger, M.R.; Scharl, M.; Wojtal, K.A.; Fischbeck-Terhalle, A.; Frey-Wagner, I.; et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles exacerbate DSS-induced colitis: Role of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Gut 2017, 66, 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorier, M.; Béal, D.; Tisseyre, C.; Marie-Desvergne, C.; Dubosson, M.; Barreau, F.; Houdeau, E.; Herlin-Boime, N.; Rabilloud, T.; Carriere, M. The food additive E171 and titanium dioxide nanoparticles indirectly alter the homeostasis of human intestinal epithelial cells in vitro. Environ. Sci. Nano 2019, 6, 1549–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Martucci, N.J.; Moreno-Olivas, F.; Tako, E.; Mahler, G.J. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle ingestion alters nutrient absorption in an in vitro model of the small intestine. NanoImpact 2017, 5, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedata, P.; Ricci, G.; Malorni, L.; Venezia, A.; Cammarota, M.; Volpe, M.G.; Iannaccone, N.; Guida, V.; Schiraldi, C.; Romano, M.; et al. In vitro intestinal epithelium responses to titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, I.S.; DeLoid, G.M.; O’Fallon, K.S.; Gaines, P.; Demokritou, P.; Bello, D. Effects of ingested food-grade titanium dioxide, silicon dioxide, iron (III) oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles on an in vitro model of intestinal epithelium: Comparison between monoculture vs. a mucus-secreting coculture model. NanoImpact 2020, 17, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Tang, Y.; Chen, B.; Hong, W.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Aguilar, Z.P.; Xu, H. Oral exposure of titanium oxide nanoparticles induce ileum physical barrier dysfunction via Th1/Th2 imbalance. Environ. Toxicol. 2020, 22934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kho, Z.Y.; Lal, S.K. The human gut microbiome-A potential controller of wellness and disease. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudefoi, W.; Moniz, K.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; Ropers, M.-H.; Walker, V.K. Impact of food grade and nano-TiO2 particles on a human intestinal community. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 106, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agans, R.T.; Gordon, A.; Hussain, S.; Paliy, O. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles elicit lower direct inhibitory effect on human gut microbiota than silver nanoparticles. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 172, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziwill-Bienkowska, J.M.; Talbot, P.; Kamphuis, J.B.J.; Robert, V.; Cartier, C.; Fourquaux, I.; Lentzen, E.; Audinot, J.-N.; Jamme, F.; Réfrégiers, M.; et al. Toxicity of food-grade TiO2 to commensal intestinal and transient food-borne bacteria: New insights using nano-SIMS and synchrotron UV fluorescence imaging. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinget, G.; Tan, J.; Janac, B.; Kaakoush, N.O.; Angelatos, A.S.; O’Sullivan, J.; Koay, Y.C.; Sierro, F.; Davis, J.; Divakarla, S.K.; et al. Impact of the food additive titanium dioxide (E171) on gut microbiota-host interaction. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Han, S.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, S.; Jia, G. Effects of oral exposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles on gut microbiota and gut-associated metabolism in vivo. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 22398–22412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocca, B.; Caimi, S.; Senofonte, O.; Alimonti, A.; Petrucci, F. ICP-MS based methods to characterize nanoparticles of TiO2 and ZnO in sunscreens with focus on regulatory and safety issues. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 630, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpone, N.; Salinaro, A.; Emeline, A. Deleterious Effects of Sunscreen Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on DNA: Efforts to Limit DNA Damage by Particle Surface Modification, Proceedings of the BiOS 2001 The International Symposium on Biomedical Optics, San Jose, CA, USA, 2001; Murphy, C.J., Ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2001; pp. 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Solaiman, S.M.; Algie, J.; Bakand, S.; Sluyter, R.; Sencadas, V.; Lerch, M.; Huang, X.-F.; Konstantinov, K.; Barker, P.J. Nano-sunscreens-a double-edged sword in protecting consumers from harm: Viewing Australian regulatory policies through the lenses of the European Union. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2019, 49, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popov, A.P.; Priezzhev, A.V.; Lademann, J.; Myllylä, R. TiO2 nanoparticles as an effective UV-B radiation skin-protective compound in sunscreens. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2005, 38, 2564–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.J.; Fang, S.W.; Cheng, W.L.; Huang, S.C.; Huang, M.C.; Cheng, H.F. Characterization of titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreen powder by comparing different measurement methods. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippe, A.; Košík, J.; Welle, A.; Guigner, J.-M.; Clemens, O.; Schaumann, G.E. Extraction and characterization methods for titanium dioxide nanoparticles from commercialized sunscreens. Environ. Sci. Nano 2018, 5, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Calle, I.; Menta, M.; Klein, M.; Maxit, B.; Séby, F. Towards routine analysis of TiO2 (nano-)particle size in consumer products: Evaluation of potential techniques. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2018, 147, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, K.; Selmani, A.; Milić, M.; Glavan, T.M.; Zapletal, E.; Ćurlin, M.; Yokosawa, T.; Vrček, I.V.; Pavičić, I. The shape of titanium dioxide nanomaterials modulates their protection efficacy against ultraviolet light in human skin cells. J. Nanopart. Res. 2020, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Directorate General for Health & Consumers. Opinion on Titanium Dioxide (Nano Form): COLIPA n° S75; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2013; ISBN 978-92-79-30114-8. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety. Opinion on Titanium Dioxide (Nano Form) as UV-Filter in Sprays; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-92-76-00201-7. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada Guidance Document-Sunscreen 2012. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/dhp-mps/alt_formats/pdf/consultation/natur/sunscreen-ecransolaire-eng.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. FDA labeling and effectiveness testing: Sunscreen drug products for over-the-counter human use—Small entity compliance Guide 2012. Fed. Regist. 2012, 77, 27591–27593. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; FDA. ”FDA/CDER/”Beitz Nonprescription Sunscreen Drug Products—Safety and Effectiveness Data Guidance for Industry. 2016. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/94249/download (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- BVL-Sonnenschutzmittel. Available online: https://www.bvl.bund.de/DE/Arbeitsbereiche/03_Verbraucherprodukte/02_Verbraucher/03_Kosmetik/06_Sonnenschutzmittel/bgs_kosmetik_sonnenschutzmittel_node.html (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Advances New Proposed Regulation to Make Sure that Sunscreens Are Safe and Effective. Available online: http://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-advances-new-proposed-regulation-make-sure-sunscreens-are-safe-and-effective (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Melquiades, F.L.; Ferreira, D.D.; Appoloni, C.R.; Lopes, F.; Lonni, A.G.; Oliveira, F.M.; Duarte, J.C. Titanium dioxide determination in sunscreen by energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence methodology. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 613, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contado, C.; Pagnoni, A. TiO2 in commercial sunscreen lotion: Flow field-flow fractionation and ICP-AES together for size analysis. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 7594–7608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipe, P.; Silva, J.N.; Silva, R.; de Castro, C.J.L.; Marques Gomes, M.; Alves, L.C.; Santus, R.; Pinheiro, T. Stratum corneum is an effective barrier to TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticle percutaneous absorption. Skin Pharm. Physiol. 2009, 22, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadrieh, N.; Wokovich, A.M.; Gopee, N.V.; Zheng, J.; Haines, D.; Parmiter, D.; Siitonen, P.H.; Cozart, C.R.; Patri, A.K.; McNeil, S.E.; et al. Lack of significant dermal penetration of titanium dioxide from sunscreen formulations containing nano-and submicron-size TiO2 particles. Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 115, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Liu, W.; Xue, C.; Zhou, S.; Lan, F.; Bi, L.; Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Zeng, F.-D. Toxicity and penetration of TiO2 nanoparticles in hairless mice and porcine skin after subchronic dermal exposure. Toxicol. Lett. 2009, 191, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelclova, D.; Navratil, T.; Kacerova, T.; Zamostna, B.; Fenclova, Z.; Vlckova, S.; Kacer, P. NanoTiO2 sunscreen does not prevent systemic oxidative stress caused by UV radiation and a minor amount of nanoTiO2 is absorbed in humans. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Du, J.; Qin, W.; Lu, M.; Cui, H.; Li, X.; Ding, S.; Li, R.; Yuan, J. Dermal exposure to nano-TiO2 induced cardiovascular toxicity through oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 44, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosera, M.; Prodi, A.; Mauro, M.; Pelin, M.; Florio, C.; Bellomo, F.; Adami, G.; Apostoli, P.; De Palma, G.; Bovenzi, M.; et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticle penetration into the skin and effects on HaCaT cells. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 9282–9297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Lu, W.; Lu, D. Penetration of titanium dioxide nanoparticles through slightly damaged skin in vitro and in vivo. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2015, 13, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel-Jeanjean, C.; Crépel, F.; Raufast, V.; Payre, B.; Datas, L.; Bessou-Touya, S.; Duplan, H. Penetration study of formulated nanosized titanium dioxide in models of damaged and sun-irradiated skins: Photochemistry and photobiology. Photochem. Photobiol. 2012, 88, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Wiench, K.; Landsiedel, R.; Schulte, S.; Inman, A.O.; Riviere, J.E. Safety evaluation of sunscreen formulations containing titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in UVB sunburned skin: An in vitro and in vivo study. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 123, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senzui, M.; Tamura, T.; Miura, K.; Ikarashi, Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Fujii, M. Study on penetration of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles into intact and damaged skin in vitro. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 35, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontier, E.; Ynsa, M.-D.; Bíró, T.; Hunyadi, J.; Kiss, B.; Gáspár, K.; Pinheiro, T.; Silva, J.-N.; Filipe, P.; Stachura, J.; et al. Is there penetration of titania nanoparticles in sunscreens through skin? A comparative electron and ion microscopy study. Nanotoxicology 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavon, A.; Miquel, C.; Lejeune, O.; Payre, B.; Moretto, P. In vitro percutaneous absorption and in vivo stratum corneum distribution of an organic and a mineral sunscreen. SPP 2007, 20, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, T.; Pallon, J.; Alves, L.C.; Veríssimo, A.; Filipe, P.; Silva, J.N.; Silva, R. The influence of corneocyte structure on the interpretation of permeation profiles of nanoparticles across skin. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2007, 260, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo-Quiros, S.; Luque-Garcia, J.L. Combination of bioanalytical approaches and quantitative proteomics for the elucidation of the toxicity mechanisms associated to TiO2 nanoparticles exposure in human keratinocytes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 127, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovic, B.; Zdravkovic, T.P.; Zdravkovic, M.; Strukelj, B.; Ferk, P. The influence of nano-TiO2 on metabolic activity, cytotoxicity and ABCB5 mRNA expression in WM-266-4 human metastatic melanoma cell line. J. BUON 2019, 24, 338–346. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, A.; Vidyasagar, S.; DeLouise, L. Physicochemical factors that affect metal and metal oxide nanoparticle passage across epithelial barriers. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2009, 1, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Fayerweather, W.E. Epidemiologic study of workers exposed to titanium dioxide. J. Occup. Med. 1988, 30, 937–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.D.; Watkins, J.P.; Tankersley, W.G.; Phillips, J.A.; Girardi, D.J. Occupational exposure and mortality among workers at three titanium dioxide plants. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2013, 56, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffetta, P.; Gaborieau, V.; Nadon, L.; Parent, M.-E.; Weiderpass, E.; Siemiatycki, J. Exposure to titanium dioxide and risk of lung cancer in a population-based study from Montreal. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2001, 27, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boffetta, P.; Soutar, A.; Cherrie, J.W.; Granath, F.; Andersen, A.; Anttila, A.; Blettner, M.; Gaborieau, V.; Klug, S.J.; Langard, S.; et al. Mortality among workers employed in the titanium dioxide production industry in Europe. Cancer Causes Control 2004, 15, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fryzek, J.P.; Chadda, B.; Marano, D.; White, K.; Schweitzer, S.; McLaughlin, J.K.; Blot, W.J. A cohort mortality study among titanium dioxide manufacturing workers in the United States. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 45, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanakumar, A.V.; Parent, M.-É.; Latreille, B.; Siemiatycki, J. Risk of lung cancer following exposure to carbon black, titanium dioxide and talc: Results from two case-control studies in Montreal. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 122, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, L.E.; Ophus, E.M.; Gylseth, B. Massive pulmonary deposition of rutile after titanium dioxide exposure. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. Sect. A Pathol. 1981, 89, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophus, E.M.; Rode, L.; Gylseth, B.; Nicholson, D.G.; Saeed, K. Analysis of titanium pigments in human lung tissue. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1979, 5, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaki Borrás, M.; Sluyter, R.; Barker, P.J.; Konstantinov, K.; Bakand, S. Y2O3 decorated TiO2 nanoparticles: Enhanced UV attenuation and suppressed photocatalytic activity with promise for cosmetic and sunscreen applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020, 207, 111883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistin, M.; Dissette, V.; Bonetto, A.; Durini, E.; Manfredini, S.; Marcomini, A.; Casagrande, E.; Brunetta, A.; Ziosi, P.; Molesini, S.; et al. A new approach to UV protection by direct surface functionalization of TiO2 with the antioxidant polyphenol dihydroxyphenyl benzimidazole carboxylic acid. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuçafy, M.P.; Manaia, E.B.; Kaminski, R.C.K.; Sarmento, V.H.; Chiavacci, L.A. Gel Based Sunscreen containing surface modified TiO2 obtained by sol-gel process: Proposal for a transparent UV inorganic filter. J. Nanomater. 2016, 2016, e8659240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaram, D.T.; Runa, S.; Kemp, M.L.; Payne, C.K. Nanoparticle-induced oxidation of corona proteins initiates an oxidative stress response in cells. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 7595–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, P.L.; Souza, W.; Gemini-Piperni, S.; Rossi, A.L.; Scapin, S.; Midlej, V.; Sade, Y.; Leme, A.F.P.; Benchimol, M.; Rocha, L.A.; et al. Rutile nano-bio-interactions mediate dissimilar intracellular destiny in human skin cells. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 2216–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Vega, S.A.C.; Molins-Delgado, D.; Barceló, D.; Díaz-Cruz, M.S. Nanosized titanium dioxide UV filter increases mixture toxicity when combined with parabens. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 184, 109565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.; Vogelsberger, W. Aqueous long-term solubility of titania nanoparticles and titanium (IV) hydrolysis in a sodium chloride system studied by adsorptive stripping voltammetry. J. Solut. Chem. 2009, 38, 1267–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowenczyk, L.; Duclairoir-Poc, C.; Barreau, M.; Picard, C.; Hucher, N.; Orange, N.; Grisel, M.; Feuilloley, M. Impact of coated TiO2-nanoparticles used in sunscreens on two representative strains of the human microbiota: Effect of the particle surface nature and aging. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 158, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gour, A.; Jain, N.K. Advances in green synthesis of nanoparticles. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velmurugan, P.; Hong, S.-C.; Aravinthan, A.; Jang, S.-H.; Yi, P.-I.; Song, Y.-C.; Jung, E.-S.; Park, J.-S.; Sivakumar, S. Comparison of the physical characteristics of green-synthesized and commercial silver nanoparticles: Evaluation of antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2017, 42, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramteke, C.; Chakrabarti, T.; Sarangi, B.K.; Pandey, R.-A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from the aqueous extract of leaves of ocimum sanctum for enhanced antibacterial activity. J. Chem. 2012, 2013, 278925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Dutta, T.; Kim, K.-H.; Rawat, M.; Samddar, P.; Kumar, P. ’Green’ synthesis of metals and their oxide nanoparticles: Applications for environmental remediation. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Aain, Q.; Khalid, N.R.; Tahir, M.B.; Rafique, M.; Rizwan, M.; Hussain, S.; Iqbal, T.; Majid, A. A review on novel eco-friendly green approach to synthesis TiO2 nanoparticles using different extracts. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2018, 28, 1552–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Tungmunnithum, D.; Hano, C.; Abbasi, B.H.; Hashmi, S.S.; Ahmad, W.; Zahir, A. The current trends in the green syntheses of titanium oxide nanoparticles and their applications. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2018, 11, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.S.M.; Francis, A.P.; Devasena, T. Biosynthesized and chemically synthesized titania nanoparticles: Comparative analysis of antibacterial activity. J. Environ. Nanotechnol. 2014, 3, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaseelan, C.; Rahuman, A.A.; Roopan, S.M.; Kirthi, A.V.; Venkatesan, J.; Kim, S.-K.; Iyappan, M.; Siva, C. Biological approach to synthesize TiO2 nanoparticles using Aeromonas hydrophila and its antibacterial activity. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 107, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaranjani, V.; Philominathan, P. Synthesize of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using moringa oleifera leaves and evaluation of wound healing activity. Wound Med. 2016, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, L.; Qian, Y.; Lou, H.; Yang, D.; Qiu, X. Facile and green preparation of high UV-blocking lignin/titanium dioxide nanocomposites for developing natural sunscreens. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 15740–15748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References Year | Properties of the Formulation (Type of Emulsion, Size, Structure of TiO2 NPs) | Type of Study | Penetration through the SC? Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pelclova et al. [100] 2019 | 43 nm, oil-free formulation, crystalline structure not specified | in vivo, human participants | Yes Absorption of TiO2 NPs through human skin—detectable levels in blood and urine |

| Zhang et al. [101] 2019 | 15–40 nm, for in vivo study nano-TiO2 solution was dripped on the skin of the mice | in vitro—HUVEC, in vivo—Balb/c mice | not indicated in vitro—increase in ROS and sICAM-1 levels, a decrease in cell viability; in vivo—increase in ROS-dependent markers concentration in mouse serum Protective effects of vitamin E demonstrated |

| Crosera et al. [102] 2015 | 38 nm, suspension of commercial TiO2 nanopowder dispersed in synthetic sweat | in vitro, human abdominal skin (intact and damaged by needle-abrasion technique) | No

No penetration of TiO2 NPs in either intact or damaged skin |

| Xie et al. [103] 2015 | 20 nm, rod-shaped rutile-type TiO2 NPs radiolabeled solution (1 mg/mL) | in vitro, rat skin: intact and slightly damaged with sodium lauryl sulphate (SLS) solution | No No penetration of TiO2 NPs in either intact or damaged skin, both in vitro and in vivo |

| Miquel-Jeanjean et al. [104] 2012 | 20–30 nm × 50–150 nm, needle-shaped particles, water-in-oil commercial emulsion | in vitro, four specimens of domestic pig ear skin: intact, damaged (stripped), irradiated, damaged and irradiated | No TiO2 NPs remained in the uppermost layers of the SC, even if the skin barrier function was impaired |

| Monteiro-Riviere et al. [105] 2011 | 10 × 50 nm, mean agglomerates 200 nm; o/w and w/o commercial formulations; rutile | in vitro—skin in flow-through diffusion cells; in vivo—weanling white Yorkshire pig skin | Minimal penetration of TiO2 NPs into the upper epidermal layers: in vitro—epidermal penetration, minimal transdermal absorption; in vivo—Ti within the epidermis and superficial dermis, no transdermal absorption detected; UV-B sunburned skin slightly enhanced the SC penetration |

| Sadrieh et al. [98] 2010 | Sunscreen formulation with: uncoated NPs (anatase and rutile): 30–50 nm, coated NPs (rutile): 20–30 nm in diameter and 50–150 in length, submicron particles (rutile): 300–500 nm | in vivo, Yucatan minipig skin | No No structural abnormalities in the skin cells observed |

| Filipe et al. [97] 2009 | Sunscreen (hydrophobic) formulation with: TiO2: not indicated TiO2 and ZnO: not indicated Coated rutile TiO2 material: 20 nm | in vivo, human participants | No Levels of TiO2 NPs too low for detection beneath the SC, no toxic effects |

| Senzui et al. [106] 2009 | Rutile TiO2 NPs, noncoated and coated; 35, 10 × 100, and 250 nm; 10% cyclopentasiloxane suspension | in vitro, Yucatan micropig skin: intact, stripped and hairless | No No penetration through viable skin, however, TiO2 particles penetrated relatively deeply into the skin, possibly via empty hair follicle |

| Wu et al. [99] 2009 | TiO2 powders suspensions: anatase: 4 and 10 nm, rutile: 25, 60, 90 nm, anatase/rutile: 21 nm (P25) | in vitro—porcine skin,

in vivo—hairless mice | Yes Toxic effects after subchronic exposure |

| Gontier et al. [107] 2008 | Formulations: carbomergel with Degussa P25 (mixture of rutile and anatase, NPs of average size 21 nm, uncoated, approximately spherical platelets), hydrophobic basisgel with Eusolex T-200 (rutile, 20 × 100 nm, coated with Al2O3 and SiO2, lanceolate shape), polyacrylategel with Eusolex T-2000, a commercial sunscreen | Samples of: porcine skin; human skin (dorsal region and buttocks); human skin grafted to SCID-mice | No Porcine skin: TiO2 NPs found only on the surface of the outermost SC layer; human skin: penetration of NPs only into 10 μm layer of the SC; human skin grafted to SCID-mice: TiO2 NPs attached to the corneocytes |

| Mavon et al. [108] 2007 | Formulation: w/o emulsion containing 3% TiO2 NPs with a mean diameter of 20 nm | in vitro—abdominal/face skin from human donors, in vivo—upper arms skin of human donors | No No TiO2 NPs detected in the follicle, viable epidermis or dermis. TiO2 NPs accumulation in the uppermost layers of the SC (also in opened infundibulum) |

| Pinheiro et al. [109] 2007 | Commercial sunscreen formulation | samples of human skin: healthy and psoriatic, from sacral-lumbal region | No In normal skin, TiO2 NPs were retained at the outermost layers of SC, in psoriatic skin, the penetration was slightly facilitated, but in both types of skin, the NPs did not reach living cell layers |

| Type of Usage/Application of TiO2 NPs | Conclusions | |

|---|---|---|

Food additive E171 | The absorption of TiO2 from the digestive tract. | Generally considered as extremely low. |

| Safety of the long-term dietary exposure to TiO2 NPs. | Still uncertain: potential toxic effects may concern the absorption, distribution, and accumulation of TiO2 NPs. | |

| Potential risks caused by TiO2 NPs. | Genotoxicity, inflammatory response, carcinogenesis. | |

| Lack of established, acceptable daily intake limits. | ||

Sunscreen formulation | Penetration of TiO2 NPs through the SC. | Lack of certainty. |

| Generation of ROS on the skin surface and underneath—potential penetration through the skin and harmful effects? | Some evidence on the increase in oxidative stress marker levels has been reported. | |

| Lack of standardized guidelines for the quality control of sunscreens. | ||

| Type of Usage/Application of TiO2 NPs | Perspectives |

|---|---|

Food additive E171 | Conducting a thorough safety assessment of E171 (especially its nanofraction). |

| Developing surface modification methods (e.g., to decrease the absorption rate) as well as green synthesis technologies. | |

| Establishing E171 daily intake levels considering different particle sizes, polymorphic structures, surface modifications, etc. | |

Sunscreen formulation | Providing complete assessment of the risk associated with the usage of TiO2 NPs-containing sunscreens. |

| Improving the action of TiO2 NPs by their surface modification and green synthesis. | |

| Providing official guidelines for sunscreen manufacturers. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Musial, J.; Krakowiak, R.; Mlynarczyk, D.T.; Goslinski, T.; Stanisz, B.J. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Food and Personal Care Products—What Do We Know about Their Safety? Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10061110

Musial J, Krakowiak R, Mlynarczyk DT, Goslinski T, Stanisz BJ. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Food and Personal Care Products—What Do We Know about Their Safety? Nanomaterials. 2020; 10(6):1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10061110

Chicago/Turabian StyleMusial, Joanna, Rafal Krakowiak, Dariusz T. Mlynarczyk, Tomasz Goslinski, and Beata J. Stanisz. 2020. "Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Food and Personal Care Products—What Do We Know about Their Safety?" Nanomaterials 10, no. 6: 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10061110

APA StyleMusial, J., Krakowiak, R., Mlynarczyk, D. T., Goslinski, T., & Stanisz, B. J. (2020). Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Food and Personal Care Products—What Do We Know about Their Safety? Nanomaterials, 10(6), 1110. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10061110