Abstract

The success of an implant depends on the type of biomaterial used for its fabrication. An ideal implant material should be biocompatible, inert, mechanically durable, and easily moldable. The ability to build patient specific implants incorporated with bioactive drugs, cells, and proteins has made 3D printing technology revolutionary in medical and pharmaceutical fields. A vast variety of biomaterials are currently being used in medical 3D printing, including metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites. With continuous research and progress in biomaterials used in 3D printing, there has been a rapid growth in applications of 3D printing in manufacturing customized implants, prostheses, drug delivery devices, and 3D scaffolds for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. The current review focuses on the novel biomaterials used in variety of 3D printing technologies for clinical applications. Most common types of medical 3D printing technologies, including fused deposition modeling, extrusion based bioprinting, inkjet, and polyjet printing techniques, their clinical applications, different types of biomaterials currently used by researchers, and key limitations are discussed in detail.

1. Introduction

Three-dimensional printing is a process of building 3D objects from a digital file. In this process, a digital 3D object is designed using computer aided design (CAD) software. SolidWorks, AutoCAD, and ZBrush are some examples of popular CAD software used commercially in industries. Blender, FreeCAD, Meshmixer, and SketchUp are some examples of the freeware commonly used to make 3D models. These 3D objects are saved in a 3D printer-readable file format. The most common universal file formats used for 3D printing are STL (stereolithography) and VRML (virtual reality modeling language). Additive manufacturing file format (AMF), GCode, and ×3g are some of the other 3D printer readable file formats. Figure 1 shows the steps involved in 3D printing of an object from a CAD design.

Figure 1.

Sequential steps involved in a 3D printing process. (A) Designed 3D computer aided design (CAD) model; (B) Stereolithography (STL) file of the model; (C) Slicing or 3D printing software; (D) 3D printed object.

In additive manufacturing, material is laid in layer-by-layer fashion in the required shape, until the object is formed. Although the term 3D printing is used as a synonym for additive manufacturing, there are several different fabricating processes involved in this technology. Depending on the 3D printing process, additive manufacturing can be classified into four categories, including extrusion printing, material sintering, material binding, and object lamination. Table 1 shows a broad classification of the different types of 3D printing techniques and their working principles.

Table 1.

Types of 3D printing technologies.

The 3D printing technology has been in use more than three decades in the automobile and aeronautical industries. In the medical field, the use of this technology was limited only to 3D printing of anatomical models for educational training purposes. Only with the recent advancements in developing novel biodegradable materials has the use of 3D printing in medical and pharmaceutical fields boomed. Today, additive manufacturing technology has wide applications in the clinical field and is rapidly expanding. It has revolutionized the healthcare system by customizing implants and prostheses, building biomedical models and surgical aids personalized to the patient, and bioprinting tissues and living scaffolds for regenerative medicine. Table 2 shows the applications of 3D printing technology in various sectors.

Table 2.

Applications of 3D printing.

Biomaterials are natural or synthetic substances that are in contact with biological systems, and help to repair, replace, or augment any tissue or organ of the body for any period of time. Based on the chemical nature of the substances, biomaterials used in 3D printing are broadly classified into four categories, as show in Table 3. An ideal 3D printing biomaterial should be biocompatible, easily printable with tunable degradation rates, and morphologically mimic living tissue.

Table 3.

Biomaterials classification with their advantages, disadvantages, and applications.

The selection of biomaterial for a 3D printing mechanism depends on the application of end product. For instance, biomaterial used for orthopedic or dental applications should have high mechanical stiffness and prolonged biodegradation rates. By contrast, for dermal or other visceral organ applications, the biomaterial used should be flexible and have faster degradation rates. The majority of biomaterials used in current medical 3D printing technology, such as metals, ceramics, hard polymers, and composites, are stiff, and thus widely used for orthodontic applications. Soft polymers, including hydrogels, are widely used in bioprinting cells for tissue/organ fabrication. The hydrogel microenvironment mimics the extracellular matrix of a living tissue, and thus, cells are easily accommodated.

2. Commonly Used 3D Printing Technologies in the Medical Field

Among the various types of 3D printing techniques described in the Table 1, FDM, extrusion based bioprinting, inkjet, and polyjet are the most common types of additive manufacturing techniques used in the medical field.

2.1. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) or Free Form Fabriction (FFF)

FDM is the most common and inexpensive type of additive manufacturing technology. In this technique, a thermoplastic filament is passed through a heated print head and is laid down on to the build platform in layer-by-layer fashion, until the required object is formed. MakerBot, Ultimaker, Flashforge, and Prusa are some of the commercially available inexpensive desktop 3D printers. These printers are limited by the variety of the materials being used, and produce lower resolution objects. Expensive FDM printers, which can use wide varieties of materials and can print at higher resolutions are also available, such as Stratasys 3D printers. FDM printers can accommodate more than one print head, and thus, can print multiple types of materials at a time. Usually, among these multi-head printers, one of the print head bears a supporting filament which can be easily removed or dissolved in water. Figure 2 shows the parts of FDM 3D printer.

Figure 2.

Dual head FDM 3D printer. (A) Building material; (B) Supporting material; (C) Print heads.

ABS is the most common thermoplastic polymer used for FDM process. PLA, nylon, polycarbonate (PC), and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) are some of the other commonly used printing filaments. Lactic acid-based polymers, including PLA and PCL, are well known for their biocompatible and biodegradable properties, and hence, are extensively used for medical and pharmaceutical applications. Additionally, PLA and PCL melt at low temperatures, 175 °C and 65 °C respectively, making it easy to load drugs without losing their bioactivity due to thermal degradation. These polymers undergo hydrolysis in vivo, and are eliminated through excretory pathways [6,7]. Comparatively, PCL has lower mechanical strength than PLA, and thus, used for non-load bearing applications.

Printing parameters, such as raster angle, raster thickness, and layer height, play a crucial role in fabricating biocompatible scaffolds with required pore size and mechanical strength. Combinations of materials, such as PCL/chitosan [8] or PCL/β-TCP (tricalcium phosphate) [9] are also used in the FDM process to enhance the bioactive properties of the scaffolds. FDM has the ability to build constructs quickly, with dimensional accuracy and excellent mechanical properties. Hence it is used widely for prototyping in industry. In medicine, FDM is used for fabricating customized patient-specific medical devices, such as implants, prostheses, anatomical models, and surgical guides. Various thermoplastic polymers are doped with variety of bioactive agents, including antibiotics [10], chemotherapeutics [11], hormones [12], nanoparticles [13,14], and other oral dosages [15,16] for personalized medicine. Using this technology, non-biocompatible materials, such as ABS [17] or thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), are used for creating medical models for perioperative surgical planning and simulations [18]. These models are also used as a tool to explain the procedures to the patients before they undergo surgery. Table 4 shows the types of biomaterials used in FDM technique for clinical applications.

Table 4.

Overview of the biomaterials used for FDM based 3D printing.

2.2. Extrusion Based Bioprinting

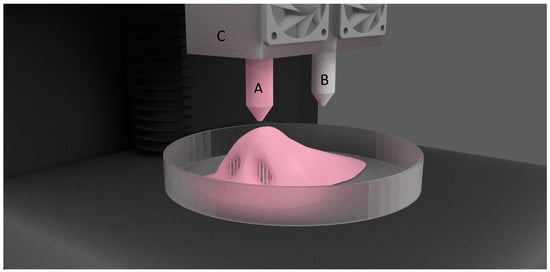

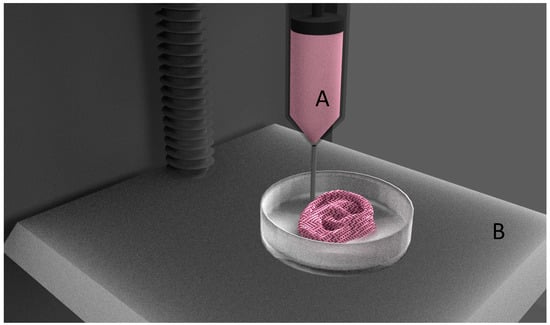

In this method, materials are extruded through a print head either by pneumatic pressure or mechanical force. Similar to FDM, materials are continuously laid in layer-by-layer fashion until the required shape is formed, as shown in Figure 3. Since this process does not involve any heating procedures, it is most commonly used for fabricating tissue engineering constructs with cells and growth hormones laden. Bioinks are the biomaterials laden with cells and other biological materials, and used for 3D printing. This 3D printing process allows for the deposition of small units of cells accurately, with minimal process-induced cell damage. Advantages such as precise deposition of cells, control over the rate of cell distribution and process speed have greatly increased the applications of this technology in fabricating living scaffolds.

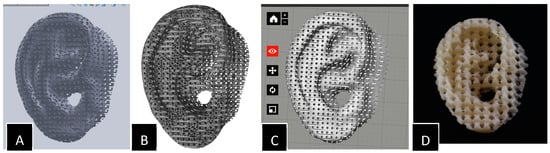

Figure 3.

Extrusion based bioprinting. (A) Bioink; (B) Build platform.

A wide range of materials with varied viscosities and high cell density aggregates can be 3D printed using this technique. A large variety of polymers are under research for the use in bioprinting technology. Natural polymers, including collagen [20], gelatin [21], alginate [22], and hyaluronic acid (HA) [23], and synthetic polymers, such as PVA [24] and polyethylene glycol (PEG), are commonly used in bioinks for 3D printing. Often these bioinks are post-processed either by chemical or UV crosslinking to enhance the constructs mechanical properties. Depending on the type of polymer used in the bioink, biological tissues and scaffolds of varied complexity can be fabricated. Multiple print heads carrying different types of cell lines for printing a complex multicellular construct can be possible with this technique. Lee et al., have used six extrusion headed 3D printer with six different bioinks, including PEG as a sacrificial ink to fabricate a living human ear [25]. Laronda et al., has used this extrusion bioprinting to fabricate gelatin based ovarian implants which can accommodate ovarian follicles. These implants restored the ovarian functions of the sterilized mice, and they even bore offspring [21].

Extrusion bioprinting has been used for fabricating scaffolds for regeneration of bone [26], cartilage [22], aortic valve [27], skeletal muscle [28], neuronal [29], and other tissues. In spite of all this success, material selection and mechanical strength still remains a major concern for bioprinting. Fabricating vascularization within a complex tissue is still an unanswered problem faced by this technology. To address this issue, researchers have focused on using sacrificial materials, which are incorporated within the construct while 3D printing, and are removed in post-processing, leaving the void spaces to act as vascularization channels [30]. Table 5 shows some of the biomaterials currently used by researchers, and their applications.

Table 5.

Biomaterials used for extrusion based bioprinting.

2.3. Material Sintering

In material sintering type of 3D printing technique, the powdered form of printing material in a reservoir is fused into a solid object, either by using physical (UV/laser/electron beam) or chemical (binding liquid) sources. SLA type is the oldest and widely used technology among metal sintering 3D printers. Unlike extrusion based printers, there is no contact between the print head and printing object. The objects can be 3D printed with high accuracy and resolution with this technique. The major limitation of this technology includes limited availability of photocurable polymer resins. Majority of the SLA resins currently available are based on low molecular weight polyacrylate or epoxy resins. For biomedical applications, polymer ceramic composite resins, made up of hydroxyapatite based calcium phosphate salts, are commonly used.

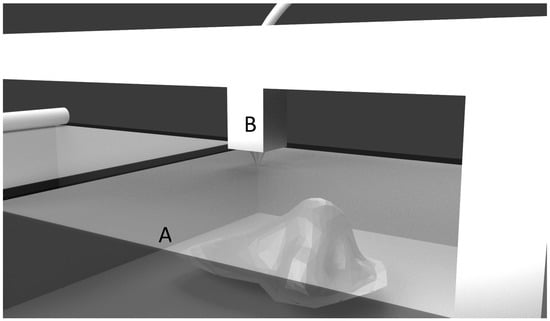

2.4. Inkjet or Binder Jet Printing

This process is similar to SLS; instead of fusing the powder bed with laser or electron beam, binding liquid is selectively dropped on to the powdered bed to bind the materials in a layer-by-layer fashion as shown in Figure 4. This process is continued until the final object is formed. Thermal and piezoelectric are two types of printing heads used in this technique. In thermal print head systems, an electric heating unit is present inside the deposition head, which vaporizes the binding material to form a vapor bubble. This vapor bubble expands due to pressure, and comes out of the print head as a droplet. Whereas in the piezoelectric print head system, the voltage pulse in the print head induces a volumetric change (changes in pressure and velocity) in the binder liquid, resulting in the formation of a droplet. These printers are known for their precise deposition of the binder liquid with speed and accuracy.

Figure 4.

Inkjet 3D printing. (A) Powdered bed; (B) Binding liquid spraying nozzle.

Water, phosphoric acid, citric acid, PVA, poly-DL-lactide (PDLLA) are some of the commonly used binding materials for inkjet 3D printing. A wide range of powdered substances, including polymers and composites, are used for medical and tissue engineering applications. Finished 3D printed objects are often post-processed to enhance the mechanical properties. Wang et al., have used phosphoric acid and PVA as binding liquids to bind HA/β-TCP powders for bone tissue regeneration applications. The accuracy and mechanical strength of constructs printed using phosphoric acid were higher than constructs printed using PVA [35]. Sandler et al., have fabricated precise and personalized dosage forms using concentrated solutions of paracetamol, theophylline, and caffeine [36]. Uddin et al., have surface coated metallic transdermal needles with chemotherapeutic agents using Soluplus, a copolymer of PVC–PVA–PEG, for transdermal drug delivery [37]. Table 6 shows the types of binding liquids and respective powder materials used for inkjet printing.

Table 6.

Biomaterials used for inkjet printing.

2.5. Polyjet Printing

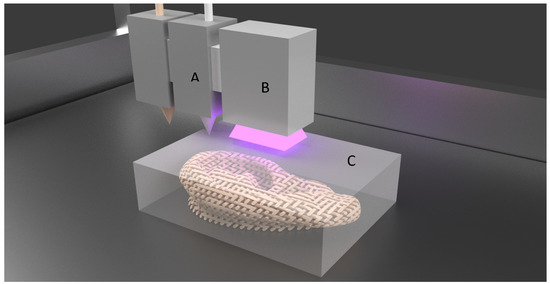

Similar to inkjet printing, layers of photopolymer resin are jetted on to the build platform and are simultaneously cured using UV light source, as shown in Figure 5. Unlike inkjet process, multiple types of materials can be jetted simultaneously and cured. This gives us the ability to fabricate a complex multi-material object. Due to these capabilities, polyjet is widely used in the medical field to fabricate anatomical models for surgical planning and pre-operative simulations. High resolution objects with varied modular strengths can be 3D printed with high dimensional accuracy using polyjet technique. Since the UV source is right next to the jetting nozzle and cures the resin instantaneously, post-processing of the construct will not be necessitated. This technology is relatively new to the additive manufacturing field. Many types of photopolymers, such as ABS like, Veroclear, Verodent, and Fullcure are commercially available for use in polyjet printing. Table 7 shows some of the photopolymers used in medical applications.

Figure 5.

Polyjet 3D printer. (A) Nozzle spraying photopolymer; (B) UV source; (C) Supporting material.

Table 7.

Biomaterials used for polyjet printing.

2.6. Laminated Object Manufacturing

In this type of 3D printing technology, thin layers of paper, plastic, or metal sheets are glued together in layer-by-layer fashion, and cut into the required shape using a metallic cutter or laser. This process is inexpensive, fast, and easy to use. It fabricates relatively lower resolution objects and is used for multicolor prototyping.

3. Limitations

Although 3D printing has the ability to fabricate on-demand, highly personalized complex designs at low costs, this technology’s medical applications are limited due to lack of diversity in biomaterials. Even with the availability of variety of biomaterials including metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites, medical 3D printing is still confined by factors such as biomaterial printability, suitable mechanical strength, biodegradation, and biocompatible properties.

Usually, in extrusion based bioprinting, higher concentrations of polymers are used in fabricating bioinks to obtain structural integrity of the end product. This dense hydrogel environment limits the cellular network and functional integration of the scaffold. For any moderate sized biological scaffold to be functional, vascularization is of utmost importance, and is not possible with the current 3D printing technology. Small scale scaffolds currently printed in the laboratories of researchers can easily survive through diffusion, but a life-size functional organ must have a profuse vascularization. To address this problem, incorporation of sacrificial materials during the scaffold fabrication has been used by many researchers. These materials fill up the void spaces, providing mechanical support to the printing materials, and once constructs are fabricated, they are removed by post-processing methods. Many sacrificial/fugitive materials including carbohydrate glass [55], pluronic glass [56], and gelatin microparticles [57] are currently under investigation [5].

Additionally, design induced limitations cause material discontinuity, due to poor transformation of complex CAD design into machine instructions. Process induced limitations include differences in porosities of CAD object and finished 3D printed product [58].

4. Conclusions

In summary, 3D printing has been revolutionizing the medical field, and is still rapidly expanding. Popular clinical applications include fabrication of patient-specific implants and prostheses; engineering scaffolds for tissue regeneration and biosynthetic organs; personalization of drug delivery systems; and anatomical modeling for perioperative simulations. The use of 3D printing in the medical field is continuously growing, due to its capabilities, such as personalization of medicine, cost efficiency, speed, and enhanced productivity [59]. With the advancement in 3D modeling software and mechanics of the printing machine, the dimensional precision, speed, and tunability of a 3D printer has been vastly improved. Using finite element analysis, the change in the mechanical properties of the finished product with respect to printing parameters can be simulated, and best suiting parameters can be obtained beforehand. Even with all these advancements, medical 3D printing is still budding and has incredible potential.

Currently, there are only a limited number of biodegradable polymers available for 3D printing. Most of these 3D printing biomaterials are used for either drug delivery or space-filling implantation purposes. Therefore, there is a major need for research to fabricate novel biopolymers with tunable bio-properties and that can restore functionality at the site of application. Inexpensive, readily available lactic acid based polymers (such as PLA and PCL) are focused on, mainly due to their abilities to perform well in most types of 3D printing technologies. Additionally, they have excellent mechanical and biodegradable properties. These polymers are also mixed with traditional biomaterials (such as HA, TCP) and used as composites to provide higher printability, mechanical stability, and greater tissue integration for orthopedic applications.

With continuous research in bioprinting and biomaterials technology, we are getting closer to fabricating life-sized, fully functional 3D printed organs. Bioprinting is still in its early stages, where many researchers have proved the feasibility of 3D printing a functional organ in a laboratory. Soon, there will be an advancement in use of these biomaterials/bioinks from labs to clinical trials, and eventually, in everyday clinical practice. This could be a potential solution to address the problem of continuous organ donor’s shortage. Moreover, the ability of the 3D printer to fabricate tissues/organs from the host cells will reduce the immune response of the implant, and in turn, reduce tissue rejection.

Acknowledgments

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author Contributions

Authors Karthik Tappa and Udayabhanu Jammalamadaka contributed equally.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Belhabib, S.; Guessasma, S. Compression performance of hollow structures: From topology optimisation to design 3D printing. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2017, 133, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guessasma, S.; Nouri, H.; Roger, F. Microstructural and Mechanical Implications of Microscaled Assembly in Droplet-based Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing. Polymers 2017, 9, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligon, S.C.; Liska, R.; Stampfl, J.; Gurr, M.; Mülhaupt, R. Polymers for 3D Printing and Customized Additive Manufacturing. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10212–10290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Guessasma, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, W.; Nouri, H.; Belhabib, S. Microstructural defects induced by stereolithography and related compressive behaviour of polymers. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 251, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrycky, C.; Wang, Z.; Kim, K.; Kim, D.H. 3D bioprinting for engineering complex tissues. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezwan, K.; Chen, Q.Z.; Blaker, J.J.; Boccaccini, A.R. Biodegradable and bioactive porous polymer/inorganic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3413–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godbey, W.T.; Atala, A. In vitro systems for tissue engineering. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 961, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Wang, S.J.; Zhao, X.R.; Zhu, Y.F.; Yu, J.K. 3D-printed poly (ϵ-caprolactone) scaffold integrated with cell-laden chitosan hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, J.-H.; Won, J.-Y.; Park, J.-H.; Bae, J.-H.; Ahn, G.; Kim, C.-H.; Lim, D.-H.; Cho, D.-W.; Yun, W.-S.; Bae, E.-B.; et al. Effects of 3D-Printed Polycaprolactone/β-Tricalcium Phosphate Membranes on Guided Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, D.; Tappa, K.; Jammalamadaka, U.; Weisman, J.; Woerner, J. The Use of 3D Printing in the Fabrication of Nasal Stents. Inventions 2017, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisman, J.A.; Nicholson, J.C.; Tappa, K.; Jammalamadaka, U.; Wilson, C.G.; Mills, D.K. Antibiotic and chemotherapeutic enhanced three-dimensional printer filaments and constructs for biomedical applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Tappa, K.; Jammalamadaka, U.; Ballard, D.H.; Bruno, T.; Israel, M.R.; Vemula, H.; Meacham, J.M.; Mills, D.K.; Woodard, P.K.; Weisman, J.A. Medication eluting devices for the field of OBGYN (MEDOBGYN): 3D printed biodegradable hormone eluting constructs; a proof of concept study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horst, D.J.; Tebcherani, S.M.; Kubaski, E.T.; De Almeida Vieira, R. Bioactive Potential of 3D-Printed Oleo-Gum-Resin Disks: B. papyrifera; C. myrrha; and S. benzoin Loading Nanooxides—TiO2, P25, Cu2O; and MoO3. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2017, 2017, 6398167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisman, J.; Jammalamadaka, U.; Tappa, K.; Mills, D. Doped Halloysite Nanotubes for Use in the 3D Printing of Medical Devices. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyanes, A.; Det-Amornrat, U.; Wang, J.; Basit, A.W.; Gaisford, S. 3D scanning and 3D printing as innovative technologies for fabricating personalized topical drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 2016, 234, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyanes, A.; Wang, J.; Buanz, A.; Martínez-Pacheco, R.; Telford, R.; Gaisford, S.; Basit, A.W. 3D Printing of Medicines: Engineering Novel Oral Devices with Unique Design and Drug Release Characteristics. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 4077–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Wang, H.; Xue, Y.; Yuan, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Z.; Dong, E.; Liu, B.; Liu, W.; Cromeens, B.; et al. Freeform fabrication of tissue-simulating phantom for potential use of surgical planning in conjoined twins separation surgery. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.-J.; Ren, J.-A.; Wang, G.-F.; Li, Z.-A.; Wu, X.-W.; Ren, H.-J.; Liu, S. 3D-printed “fistula stent” designed for management of enterocutaneous fistula: An advanced strategy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 7489–7494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, C.R.; Serra, T.; Oliveira, M.I.; Planell, J.A.; Barbosa, M.A.; Navarro, M. Impact of 3-D printed PLA- and chitosan-based scaffolds on human monocyte/macrophage responses: Unraveling the effect of 3-D structures on inflammation. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, S.; Puetzer, J.L.; Mason, B.N.; Reinhart-King, C.A.; Bonassar, L.J. 3D Bioprinting of Spatially Heterogeneous Collagen Constructs for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 1800–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laronda, M.M.; Rutz, A.L.; Xiao, S.; Whelan, K.A.; Duncan, F.E.; Roth, E.W.; Woodruff, T.K.; Shah, R.N. A bioprosthetic ovary created using 3D printed microporous scaffolds restores ovarian function in sterilized mice. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markstedt, K.; Mantas, A.; Tournier, I.; Martínez Ávila, H.; Hägg, D.; Gatenholm, P. 3D Bioprinting Human Chondrocytes with Nanocellulose–Alginate Bioink for Cartilage Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.; Hägg, D.A.; Forsman, A.; Ekholm, J.; Nimkingratana, P.; Brantsing, C.; Kalogeropoulos, T.; Zaunz, S.; Concaro, S.; Brittberg, M.; et al. Cartilage Tissue Engineering by the 3D Bioprinting of iPS Cells in a Nanocellulose/Alginate Bioink. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z.; Parisi, C.; Di Silvio, L.; Dini, D.; Forte, A.E. Cryogenic 3D Printing of Super Soft Hydrogels. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-S.; Hong, J.M.; Jung, J.W.; Shim, J.-H.; Oh, J.-H.; Cho, D.-W. 3D printing of composite tissue with complex shape applied to ear regeneration. Biofabrication 2014, 6, 24103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillippi, J.A.; Miller, E.; Weiss, L.; Huard, J.; Waggoner, A.; Campbell, P. Microenvironments Engineered by Inkjet Bioprinting Spatially Direct Adult Stem Cells Toward Muscle- and Bone-Like Subpopulations. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, B.; Hockaday, L.A.; Kang, K.H.; Butcher, J.T. 3D bioprinting of heterogeneous aortic valve conduits with alginate/gelatin hydrogels. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013, 101, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorovich, N.E.; Alblas, J.; de Wijn, J.R.; Hennink, W.E.; Verbout, A.J.; Dhert, W.J.A. Hydrogels as Extracellular Matrices for Skeletal Tissue Engineering: State-of-the-Art and Novel Application in Organ Printing. Tissue Eng. 2007, 13, 1905–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, F.-Y.; Lin, H.-H.; Hsu, S. 3D bioprinting of neural stem cell-laden thermoresponsive biodegradable polyurethane hydrogel and potential in central nervous system repair. Biomaterials 2015, 71, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suntornnond, R.; An, J.; Chua, C.K. Roles of support materials in 3D bioprinting. Int. J. Bioprint. 2017, 3, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poldervaart, M.T.; Goversen, B.; de Ruijter, M.; Abbadessa, A.; Melchels, F.P.W.; Öner, F.C.; Dhert, W.J.A.; Vermonden, T.; Alblas, J. 3D bioprinting of methacrylated hyaluronic acid (MeHA) hydrogel with intrinsic osteogenicity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sa, M.-W.; Nguyen, B.-N.B.; Moriarty, R.A.; Kamalitdinov, T.; Fisher, J.P.; Kim, J.Y. Fabrication and evaluation of 3D printed BCP scaffolds reinforced with ZrO2 for bone tissue applications. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Pei, P.; Zhu, M.; Du, X.; Xin, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y. Three dimensional printing of calcium sulfate and mesoporous bioactive glass scaffolds for improving bone regeneration in vitro and in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Liu, A.; Shao, H.; Yang, X.; Ma, C.; Yan, S.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Gou, Z. Systematical Evaluation of Mechanically Strong 3D Printed Diluted magnesium Doping Wollastonite Scaffolds on Osteogenic Capacity in Rabbit Calvarial Defects. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, X.; Wei, Q.; Chai, W.; Wang, S.; Che, Y.; Lu, T.; Zhang, B. 3D fabrication and characterization of phosphoric acid scaffold with a HA/β-TCP weight ratio of 60:40 for bone tissue engineering applications. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandler, N.; Määttänen, A.; Ihalainen, P.; Kronberg, L.; Meierjohann, A.; Viitala, T.; Peltonen, J. Inkjet printing of drug substances and use of porous substrates-towards individualized dosing. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 3386–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.J.; Scoutaris, N.; Klepetsanis, P.; Chowdhry, B.; Prausnitz, M.R.; Douroumis, D. Inkjet printing of transdermal microneedles for the delivery of anticancer agents. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 494, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strobel, L.A.; Rath, S.N.; Maier, A.K.; Beier, J.P.; Arkudas, A.; Greil, P.; Horch, R.E.; Kneser, U. Induction of bone formation in biphasic calcium phosphate scaffolds by bone morphogenetic protein-2 and primary osteoblasts. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2014, 8, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inzana, J.A.; Trombetta, R.P.; Schwarz, E.M.; Kates, S.L.; Awad, H.A. 3D printed bioceramics for dual antibiotic delivery to treat implant-associated bone infection. Eur. Cells Mater. 2015, 30, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, R.D.; Miller, P.R.; Daniels, J.; Stafslien, S.; Narayan, R.J. Inkjet printing for pharmaceutical applications. Mater. Today 2014, 17, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Eydivand, M.; Solati-Hashjin, M.; Shafiei, S.S.; Mohammadi, S.; Hafezi, M.; Osman, N.A.A. Structure; properties; and in vitro behavior of heat-treated calcium sulfate scaffolds fabricated by 3D printing. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inzana, J.A.; Olvera, D.; Fuller, S.M.; Kelly, J.P.; Graeve, O.A.; Schwarz, E.M.; Kates, S.L.; Awad, H.A. 3D printing of composite calcium phosphate and collagen scaffolds for bone regeneration. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 4026–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzadi, A.; Solati-Hashjin, M.; Asadi-Eydivand, M.; Osman, N.A.A. Effect of layer thickness and printing orientation on mechanical properties and dimensional accuracy of 3D printed porous samples for bone tissue engineering. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickström, H.; Hilgert, E.; Nyman, J.; Desai, D.; Şen Karaman, D.; de Beer, T.; Sandler, N.; Rosenholm, J. Inkjet Printing of Drug-Loaded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles—A Platform for Drug Development. Molecules 2017, 22, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meess, K.M.; Izzo, R.L.; Dryjski, M.L.; Curl, R.E.; Harris, L.M.; Springer, M.; Siddiqui, A.H.; Rudin, S.; Ionita, C.N. 3D Printed Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Phantom for Image Guided Surgical Planning with a Patient Specific Fenestrated Endovascular Graft System. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2017, 10138, 101380P. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Ohdan, H. 3D printing model of the intrahepatic vessels for navigation during anatomical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2017, 41, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wei, H.; Zeng, F.; Li, J.; Xia, J.J.; Wang, X. Application of A Novel Three-dimensional Printing Genioplasty Template System and Its Clinical Validation: A Control Study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gear, J.I.; Cummings, C.; Craig, A.J.; Divoli, A.; Long, C.D.C.; Tapner, M.; Flux, G.D. Abdo-Man: A 3D-printed anthropomorphic phantom for validating quantitative SIRT. EJNMMI Phys. 2016, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zein, N.N.; Hanouneh, I.A.; Bishop, P.D.; Samaan, M.; Eghtesad, B.; Quintini, C.; Miller, C.; Yerian, L.; Klatte, R. Three-dimensional print of a liver for preoperative planning in living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2013, 19, 1304–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waran, V.; Narayanan, V.; Karuppiah, R.; Owen, S.L.F.; Aziz, T. Utility of multimaterial 3D printers in creating models with pathological entities to enhance the training experience of neurosurgeons. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 120, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsouras, D.; Lee, T.C.; Liacouras, P.; Ionita, C.N.; Pietilla, T.; Maier, S.E.; Mulkern, R.V. Three-dimensional printing of MRI-visible phantoms and MR image-guided therapy simulation. Magn. Reson. Med. 2017, 77, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Q.; Chen, A.; Zhang, T.; Li, G.; Zhu, Q.; Fan, X.; Ma, C.; Xu, T. Development of Three-Dimensional Printed Craniocerebral Models for Simulated Neurosurgery. World Neurosurg. 2016, 91, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, I.; Liepert, T.; Doney, E.; Leevy, W.; Liepert, D. Patient Education for Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: Preliminary Experience Using 3D-Printed Clinical Imaging Data. J. Funct. Biomater. 2017, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, D.K.; Chatzinoff, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Fulkerson, M.; Chopra, R.; Brugarolas, J.; Cadeddu, J.A.; Kapur, P.; Pedrosa, I. Development of a Patient-specific Tumor Mold Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging and 3-Dimensional Printing Technology for Targeted Tissue Procurement and Radiomics Analysis of Renal Masses. Urology 2017, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.S.; Stevens, K.R.; Yang, M.T.; Baker, B.M.; Nguyen, D.-H.T.; Cohen, D.M.; Toro, E.; Chen, A.A.; Galie, P.A.; Yu, X.; et al. Rapid casting of patterned vascular networks for perfusable engineered three-dimensional tissues. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolesky, D.B.; Truby, R.L.; Gladman, A.S.; Busbee, T.A.; Homan, K.A.; Lewis, J.A. 3D bioprinting of vascularized; heterogeneous cell-laden tissue constructs. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 3124–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, T.J.; Jallerat, Q.; Palchesko, R.N.; Park, J.H.; Grodzicki, M.S.; Shue, H.-J.; Ramadan, M.H.; Hudson, A.R.; Feinberg, A.W. Three-dimensional printing of complex biological structures by freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassana, B.O.; Guessasma, S.; Belhabib, S.; Nouri, H. Explaining the Difference between Real Part and Virtual Design of 3D Printed Porous Polymer at the Microstructural Level. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2016, 301, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventola, C.L. Medical Applications for 3D Printing: Current and Projected Uses. Pharm. Ther. 2014, 39, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).