1. Introduction

Collagen is one of the most widely utilized natural polymers in biomedical applications due to its biocompatibility, intrinsic cell-interactive motifs, and capacity to integrate with surrounding tissues [

1,

2,

3]. In the dental and craniofacial fields, collagen membranes are commonly applied as barrier materials in guided tissue and bone regeneration procedures, where controlled degradation is essential to maintain structural integrity and avoid premature loss of function [

4,

5]. Beyond barrier applications, collagen also serves as a carrier for cells, growth factors, and bioactive compounds, in which its degradation behavior directly influences mechanical stability and release characteristics [

6,

7].

Despite these advantages, collagen-based devices often exhibit relatively rapid in vivo biodegradation caused by enzymatic cleavage, hydrolytic processes, and cellular remodeling [

8,

9,

10]. Such rapid resorption may compromise intended barrier duration or sustained-release functionality, particularly when residence time must be matched to biological healing phases [

11]. Therefore, strategies to fine-tune collagen degradation, while maintaining biocompatibility, flexibility, and surgical handling, remain of practical interest for various biomedical uses.

Multiple approaches have been investigated to modulate collagen stability, including chemical crosslinking, thermal or ultraviolet treatment, polymer blending, and mineral addition [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Although these methods can enhance degradation resistance, they may also lead to drawbacks such as residual cytotoxicity, altered stiffness, reduced tissue integration, or increased processing complexity [

13,

16]. Accordingly, there is growing interest in milder modification strategies that achieve controlled stabilization through non-covalent interactions rather than permanent covalent crosslinks.

Amino-acid–mediated modulation represents one such approach. L-serine, a non-essential amino acid containing a polar hydroxyl side chain, participates in hydrogen-bonding interactions and may influence protein hydration [

17], molecular packing [

18], and supramolecular organization [

19]. Compared with other non-covalent modifiers such as sugars, polyols, or bulkier amino acids, L-serine offers a uniquely small, hydroxyl-containing side chain that can participate in hydrogen-bonding and hydration-mediated interactions while introducing minimal steric interference, making it a particularly suitable candidate for subtle modulation of collagen stability. When present within or around protein matrices, hydroxyl groups can promote additional inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonds, influence hydration shells, and subtly affect fibrillogenesis and fibril packing [

20,

21]. We hypothesized that incorporating L-serine into collagen matrices could promote additional non-covalent interactions that modestly enhance structural stability and reduce enzymatic accessibility, thereby delaying biodegradation without the need for chemical crosslinkers.

Based on this rationale, the present study focuses on a materials-oriented evaluation of collagen scaffolds supplemented with L-serine, specifically examining whether this modification alters in vivo degradation characteristics. Our aim was not to assess osteogenic or regenerative performance, but rather to determine whether L-serine incorporation can serve as a simple, biocompatible, and non-crosslinking strategy to adjust the resorption profile of collagen-based constructs. For this purpose, we prepared L-serine-containing scaffolds using hydrolyzed bovine skin collagen, a rapidly degradable collagen source commonly used for cell culture studies, which provides a sensitive model for detecting stabilization effects. We then evaluated degradation behavior through structural characterization and subcutaneous implantation. The findings are intended to provide preliminary feasibility data supporting amino-acid–assisted modulation as a gentle stabilization approach for collagen biomaterials. Although osteogenic or regenerative performance is essential for defining the suitability of a biomaterial for tissue engineering, the present study focuses specifically on structural stabilization and degradation behavior. The regenerative capacity of L-serine–modified collagen remains to be established in future biological and defect-specific models. While collagen scaffolds are frequently applied in bone regeneration, the stabilization strategy examined here is not restricted to bone-related uses; rather, the modulation of degradation behavior achieved through L-serine incorporation may be relevant to a wider range of soft- and hard-tissue engineering applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

Type I collagen derived from calf skin (bovine skin; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. C9791, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as the base material for scaffold fabrication. Lyophilized collagen was dispersed in distilled water to obtain a 2% (w/v) collagen suspension under gentle stirring at 4 °C. For the experimental groups, L-serine powder (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in distilled water and added to the collagen suspension to yield final concentrations of 10, 20, 30, or 40 wt% L-serine relative to the dry weight of collagen. The selected range of 10–40 wt% L-serine was based on preliminary solubility and formability assessments, which showed that concentrations below 10 wt% produced negligible structural modification, whereas concentrations above 40 wt% led to phase separation and impaired scaffold formation during the drying process. Using distilled water-maintained collagen in a partially hydrated, non-fibrillar state during mixing, which facilitated homogeneous incorporation of L-serine prior to drying.

The mixtures were homogenized to form collagen–L-serine hydrogels, which were then cast into flat polystyrene molds to a uniform thickness of approximately 1 mm and dried at 4 °C for 48 h to produce scaffold sheets. Following drying, the scaffold sheets had a uniform thickness of approximately 1 mm and were trimmed into rectangular specimens measuring 10 × 10 mm for in vitro analyses and 5 × 10 mm for subcutaneous implantation. Bulk density and porosity were not quantified in this study, as the focus was on degradation behavior rather than mechanical or transport properties; these parameters will be addressed in future work. The dried sheets were used for structural analyses and animal experiments. A commercially available bilayer porcine collagen membrane composed of type I and III collagen (Bio-Gide®, Geistlich Pharma, Wolhusen, Switzerland) served as a positive control.

2.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

Lyophilized samples were prepared by freeze-drying the specimens at −80 °C followed by vacuum drying (−50 °C, <0.1 mbar) for 24 h. The dried samples were mounted on a low-background Si holder. XRD patterns were collected using an Ultima IV X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å, 40 kV, 30 mA) in 2θ geometry. Data were acquired over the 2θ range of 5–80° with a step size of 0.02° and a counting time of 0.5 s per step. Phase identification was carried out by comparing diffraction peaks with the International Centre for Diffraction Data Powder Diffraction File (ICDD PDF) database. The peak intensity ratio was calculated by dividing the maximum intensity of a representative crystalline L-serine peak at 2θ = 22–23° by that of the collagen amorphous halo at 2θ = 20° using the digitized XRD profiles. XRD measurements were performed on two independently prepared specimens (n = 2).

2.3. Fourier Transforms Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Analysis

FT-IR was employed to identify the chemical structures of the samples, based on their characteristic absorption fingerprints. FT-IR spectra were obtained using an S100 spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Lyophilized samples were finely ground and mixed with spectroscopic-grade potassium bromide (KBr) to obtain transparent pellets suitable for transmission analysis, which improves spectral quality by ensuring uniform dispersion and minimizing light scattering. The KBr–sample mixtures were compressed into pellets using a hydraulic press (Specac, Orpington, UK) at 10 tons of pressure for 10 min. FT-IR spectra were obtained using an S100 spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at a resolution of 4 cm−1, recorded over the range of 450–4000 cm−1, with each spectrum representing the average of 23 scans. FT-IR analysis was conducted on two independent samples (n = 2).

2.4. Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrometer Analysis

CD spectroscopy was performed to analyze the secondary structure of the samples using a spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Easton, MD, USA). Samples were placed in a 10-mm path-length quartz high-precision cuvette (Jasco, Easton, MD, USA). Spectra were recorded from 190 to 260 nm, with each measurement averaged over three scans. Prior to measurement, baseline correction was performed using distilled water. Data were expressed as ellipticity (mdeg) as a function of wavelength. Spectra were smoothed using the Savitzky–Golay filter in the Spectra Analysis software (version 2.11.01, Jasco). CD spectra were obtained from two independently prepared samples (n = 2).

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

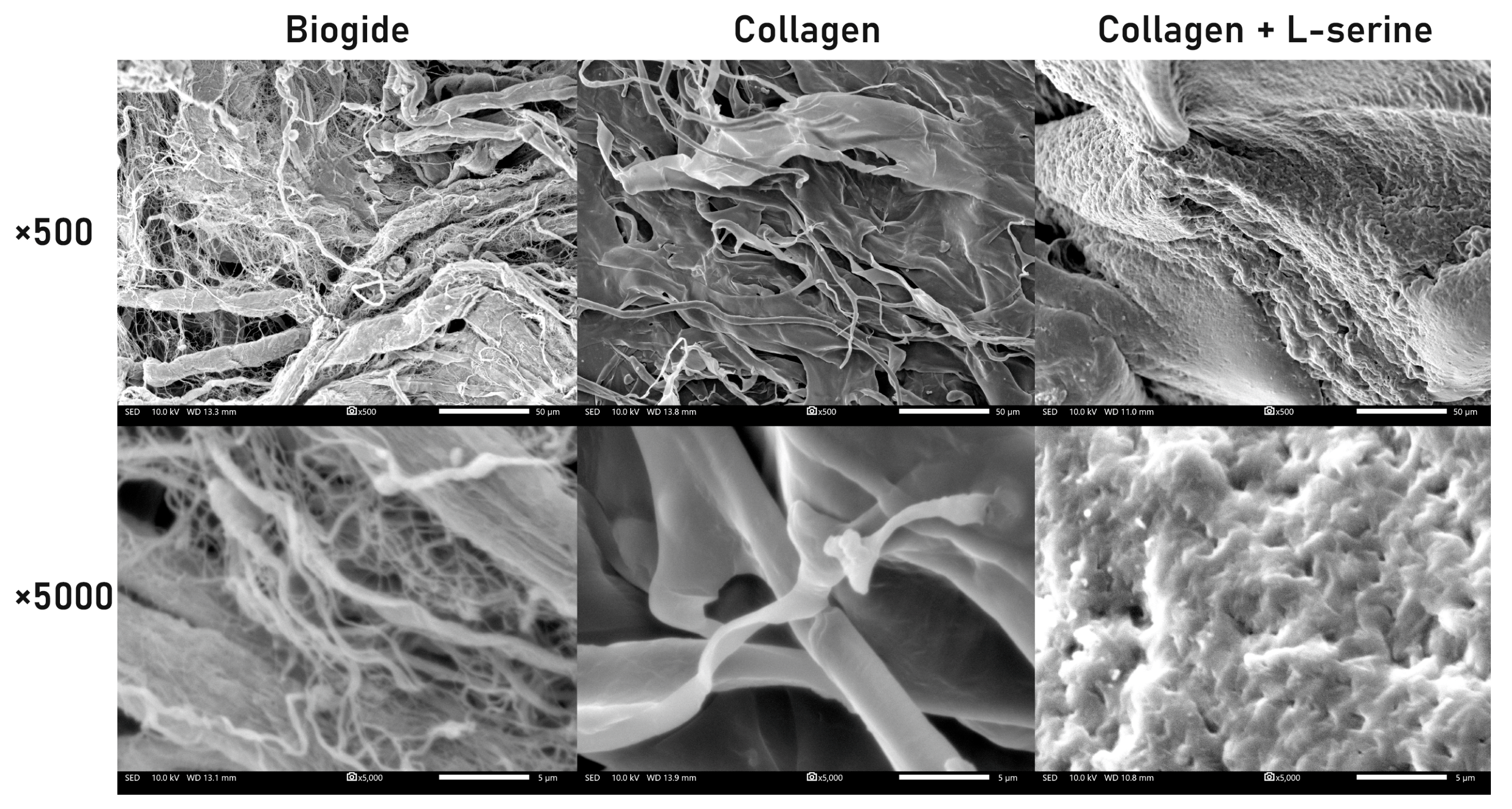

The surface morphology of Biogide®, collagen, and collagen + L-serine specimens was examined by scanning electron microscopy (JSM-IT200, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). For sample preparation, the hydrogel form of collagen + L-serine was fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at 4 °C, followed by sequential dehydration in graded ethanol solutions (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, and 100%). After dehydration, the samples were slowly dried at room temperature to minimize structural collapse and then sputter-coated with a thin platinum layer. SEM images were obtained at magnifications of ×500 and ×5000 under an accelerating voltage of 10 kV, providing detailed views of fibrillar organization and surface topography. SEM imaging was performed using two independent samples (n = 2), with representative micrographs collected from multiple regions of each specimen.

2.6. Animals’ Studies

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Gangneung-Wonju National University (GWNU-2025-12). Twenty-four male Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice (7 weeks old, 33–39.5 g) were obtained from Samtako Bio Inc. (Osan, Republic of Korea). Animals were housed two per cage and allowed a one-week acclimation period before experimentation. Environmental conditions were maintained at 20–22 °C under a 12 h light/dark cycle, with free access to food and water.

Mice were randomly assigned to three groups (n = 8 per group) according to the implanted material: (1) a commercial collagen membrane (Bio-Gide®), (2) unmodified type I collagen (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), or (3) collagen containing 40 wt% L-serine. The sample size (n = 8) was chosen in accordance with common practice for exploratory subcutaneous degradation models and was not based on a formal a priori power calculation, as the aim was to obtain preliminary biological data on scaffold persistence rather than to test a predefined statistical hypothesis. To minimize confounding factors, mice within the same cage were assigned to the same group, and cages from different groups were placed adjacently to control for cage-location effects. Group allocation was concealed from all researchers except the corresponding author, and investigators performing the experiments and analyses were blinded to the group assignments.

Mice were anesthetized by intramuscular injection of Zoletil (Virbac Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea) and Rompun (Bayer Korea, Seoul, Republic of Korea). A dorsal skin incision was made, the subcutaneous tissue was dissected, and the prepared material (20 mg) was implanted subcutaneously. The incision was closed with sutures. To prevent infection, gentamicin (5 mg/kg; Samu Median, Seoul, Republic of Korea) and tolfenamic acid (0.1 mL/kg; Samyang Anipharm, Seoul, Republic of Korea) were administered intramuscularly immediately after surgery and again on postoperative day 1.

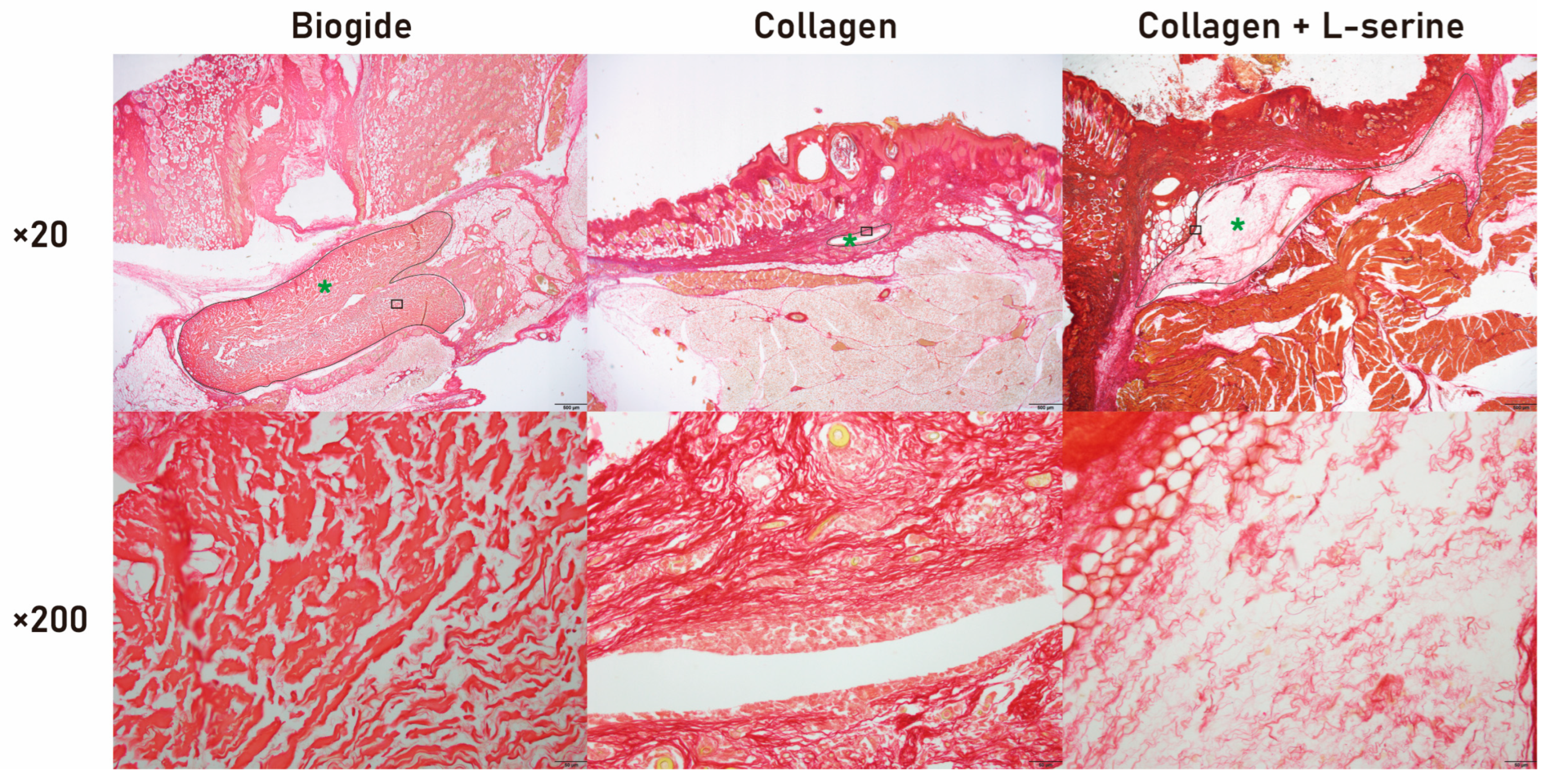

Sonographic imaging was performed using an ultrasound system (ACCUVIX V10®, Samsung Medison, Seoul, Republic of Korea) to evaluate the residual graft in the subcutaneous pocket. Sonographic imaging of the graft site was performed under anesthesia (Zoletil, intramuscular; or sevoflurane, inhalation) at the following time points: before implantation, immediately after surgery, and at 1 and 3 weeks postoperatively. At 3 weeks, mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, and the graft sites, including the underlying muscle tissue, were harvested for histological analysis. An implantation duration of three weeks was selected based on preliminary pilot observations indicating substantial degradation of collagen scaffolds within this period, which allowed clear comparison among groups. This timeframe is also consistent with previous short-term subcutaneous biodegradation studies of collagen-based materials.

Tissue specimens were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 5 µm. Picrosirius Red staining was performed for collagen visualization. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, stained with Picro Sirius Red (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rinsed with acetic acid, dehydrated, and mounted. Images were captured using a DP72 digital camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Quantification of residual graft area was performed exclusively on these histological sections. Digital images were analyzed using SigmaScan Pro 5.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The residual graft was identified based on its dense, eosinophilic collagen appearance. Using the manual tracing tool, the boundary of the remaining graft material was outlined, and the software automatically calculated the enclosed area in square millimeters. Three non-overlapping sections were measured per sample, and the mean value was used for statistical comparison.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data from sonographic imaging (residual graft area over time) and histological evaluation (percentage of residual material and collagen deposition) were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Normality of data distribution was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Homogeneity of variance was assessed using Levene’s test. Comparisons among groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 10.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

4. Discussion

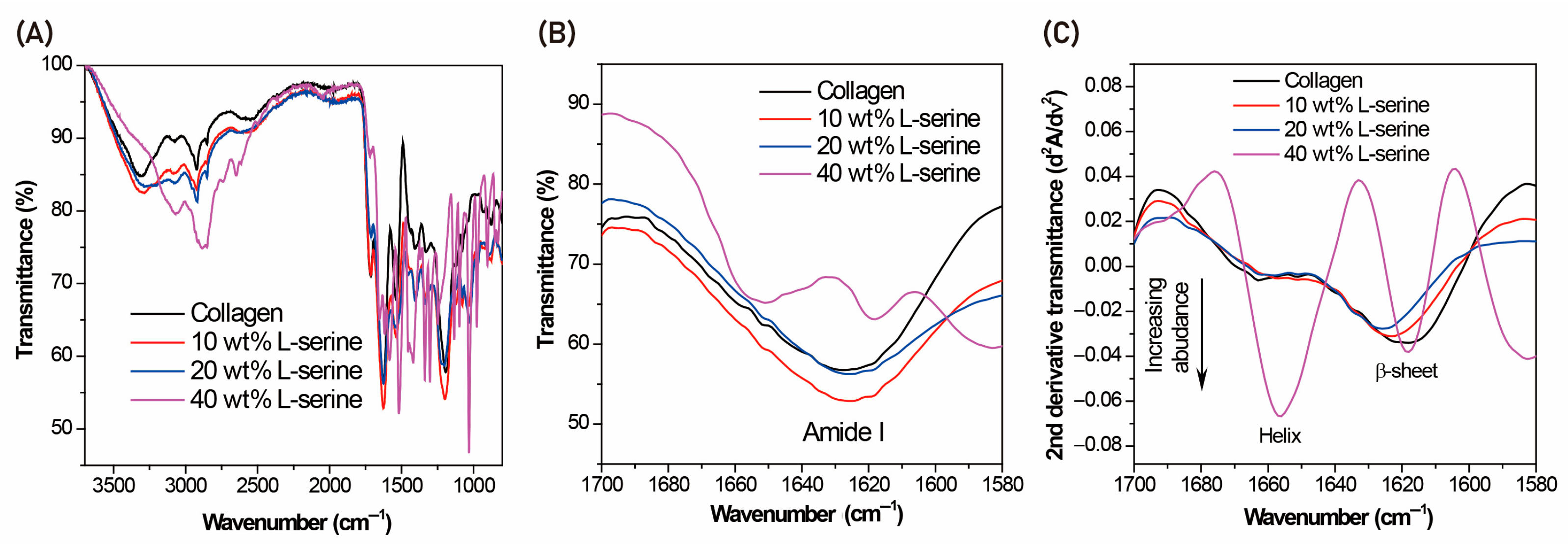

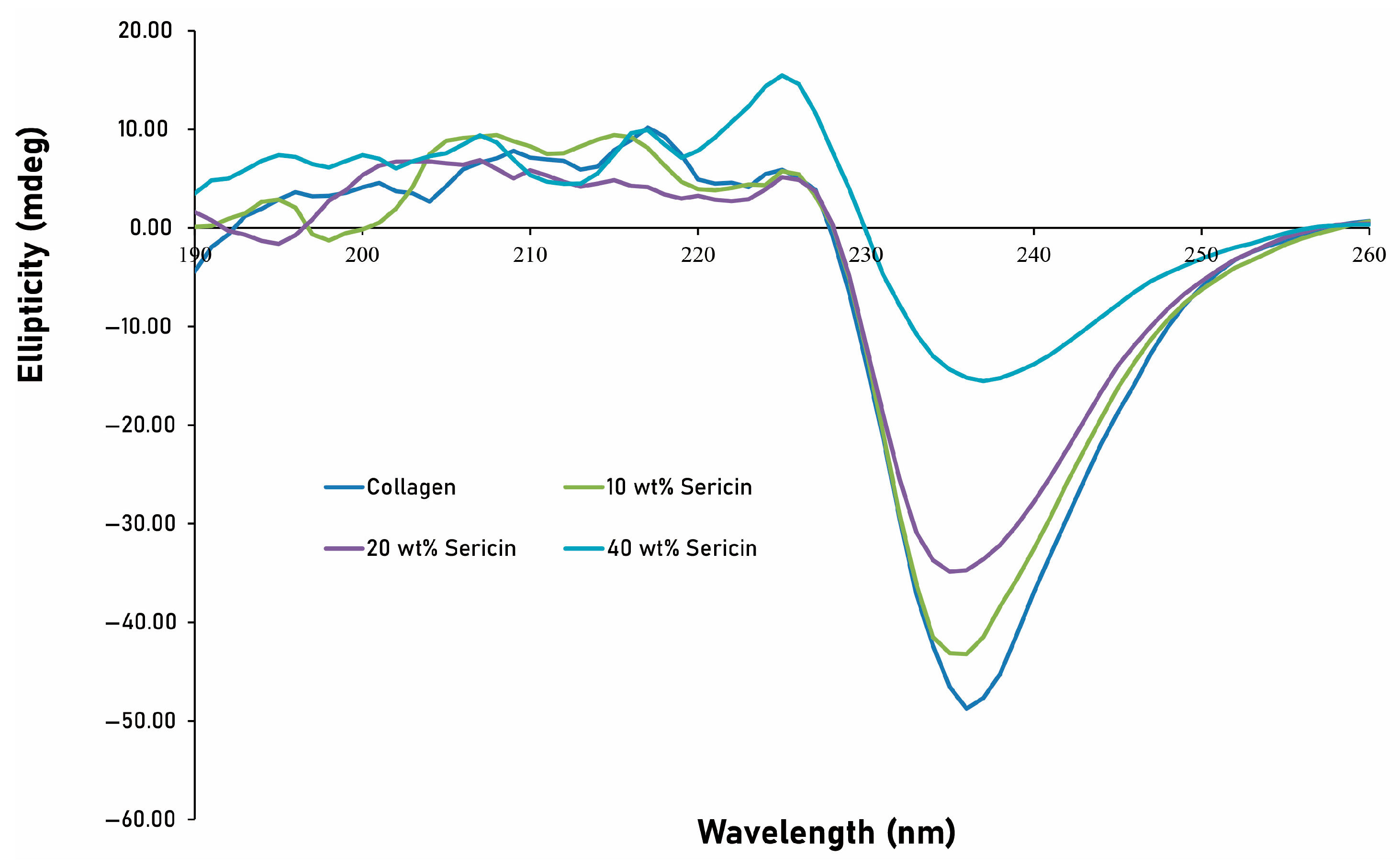

In this study, we demonstrated that incorporation of L-serine into collagen matrices modulated their structural organization and in vivo degradation profile without the use of chemical crosslinking. Structural analyses revealed that low-to-moderate concentrations of L-serine (10–30 wt%) preserved the triple-helical architecture of collagen while modestly increasing β-sheet content, whereas higher incorporation (40 wt%) resulted in the appearance of crystalline serine-associated domains and redistribution toward β-sheet enrichment (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). In vivo experiments further showed that collagen containing 40 wt% L-serine exhibited slower resorption compared with unmodified collagen, although its persistence remained lower than that of the commercially processed collagen membrane, Bio-Gide

® (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Collectively, these findings support the feasibility of amino acid–based modulation as a gentle and non-crosslinking approach for controlling collagen biodegradation.

Traditional strategies for prolonging collagen stability often rely on chemical crosslinkers or physical treatments [

11,

12,

13,

14]. While agents such as glutaraldehyde and genipin can substantively reduce enzymatic susceptibility, their use has been associated with residual cytotoxicity risks or compromised tissue integration [

16,

22]. Non-chemical approaches, such as dehydrothermal and ultraviolet treatments, may extend stability but can also alter mechanical behavior and reduce handling flexibility [

12,

13]. Polymer blending and mineral reinforcement can enhance biostability, yet these techniques may introduce fabrication complexity and reduce clinical adaptability [

13,

15]. In contrast, L-serine incorporation represents a simple, aqueous, and biocompatible modification approach that avoids harsh reagents while maintaining key intrinsic characteristics of collagen.

The stabilizing effect observed in this work is likely related to the hydroxyl-containing side chain of L-serine, which can participate in hydrogen bonding with collagen backbones and influence hydration-related interactions (

Figure 8). Moderate incorporation levels (10–30 wt%) may enhance non-covalent intermolecular packing, thereby reducing enzymatic accessibility to cleavage sites [

23,

24]. In hydrated protein matrices, hydroxyl-containing amino acids can promote both direct hydrogen bonding and water-mediated bridging interactions, leading to tighter intermolecular packing and the formation of a more structured hydration shell [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Such ‘bound’ or ordered water has reduced mobility compared with bulk water and has been associated with decreased susceptibility of collagenous substrates to enzymatic degradation, because proteolytic enzymes require both physical access and local backbone flexibility to cleave peptide bonds [

23,

24]. Consistent with this interpretation, FT-IR and CD analyses suggested partial preservation of triple-helical features under moderate doping conditions (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

In contrast, at 40 wt%, the emergence of crystalline domains and increased β-sheet signatures suggested that excessive serine content could disrupt helicity and promote aggregation (

Figure 1 and

Figure 4). These changes suggest a transition from subtle hydrogen-bond–mediated modulation to more extensive supramolecular reorganization, in which aggregation and phase separation alter packing density and generate heterogeneous regions within the scaffold. Although the 40 wt% formulation exhibited relatively slower in vivo degradation, this outcome is more plausibly explained by altered supramolecular organization and uneven enzymatic accessibility rather than preservation of triple-helical integrity. The formation of serine-rich crystalline regions and β-sheet–rich aggregates disrupt the continuity of the collagen network and modifies hydration and packing characteristics, producing effects analogous to—but ultimately distinct from—the hydrogen-bond–mediated stabilization reported for polyol-based additives [

21,

25]. At higher loadings, therefore, the balance shifts from beneficial hydrogen-bond interactions to structural alteration and aggregation, which limit any potential stabilizing effect on the collagen triple helix. It should be noted that the hydrogen-bonding and hydration-mediated explanations proposed here are mechanistic hypotheses based on indirect spectroscopic and degradation trends rather than direct measurements. This study did not quantify changes in hydration dynamics, L-serine–collagen binding interactions, or protease accessibility, which would be required to definitively establish the mechanism. Accordingly, the interpretations presented here should be viewed as plausible but provisional, and future work incorporating hydration analysis, binding assays, and controlled collagenase degradation studies will be necessary to validate and refine these mechanistic insights.

The subcutaneous implantation model provided an initial in vivo evaluation of degradation behavior (

Figure 5). As expected, unmodified collagen degraded rapidly, consistent with its well-known enzymatic susceptibility [

26,

27]. Collagen containing 40 wt% L-serine showed significantly greater residual area after 3 weeks (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), supporting the hypothesis that L-serine incorporation can delay proteolysis under physiological conditions. Bio-Gide

® remained the most stable material, reflecting performance optimization through industrial processing. While previous studies have reported biological activity of L-serine, including osteoblast-supportive and osteoclast-modulating properties [

28,

29], such cellular responses were not evaluated in the present work, and therefore no regenerative or osteogenic conclusions can be drawn based on the current data. The applicability of the L-serine–modified collagen scaffolds is not limited to bone repair. Collagen is broadly used across soft-tissue augmentation, periodontal regeneration, wound healing, and guided tissue regeneration, where controlled degradation and structural stability are important design parameters [

30]. Because this study evaluated physicochemical stabilization and in vivo persistence rather than bone-specific biological responses, further investigations—including osteogenic assays, soft-tissue interaction studies, and defect-specific in vivo models—will be required to determine the optimal clinical indication for these formulations.

This study has several strengths, including the use of complementary structural characterization methods and quantitative in vivo degradation analysis. Nonetheless, important limitations must be acknowledged. First, the implantation duration was limited to 3 weeks, which limits interpretation regarding long-term persistence. Second, only a single L-serine concentration was evaluated in vivo, preventing comprehensive assessment of dose–response relationships. Third, mechanical properties relevant to clinical handling, including tensile strength, elasticity, and suture pullout resistance, were not examined. Another limitation is the absence of In Vitro degradation assays using collagenase solutions, which would allow a clearer mechanistic understanding of collagen susceptibility under controlled enzymatic conditions. Incorporating collagenase-based assays in future studies will help correlate structural modifications with enzyme-mediated degradation kinetics. While the present work demonstrates that L-serine incorporation can modulate collagen structure and slow in vivo degradation at 40 wt%, the regenerative or osteogenic performance of the modified scaffolds was not evaluated. Such properties are essential for tissue-engineering applications. Therefore, additional investigations—including cell-based biocompatibility and differentiation assays, evaluation of host–material interactions, and assessment in defect-specific bone or soft-tissue models—will be required to determine whether L-serine–enriched collagen scaffolds meet the functional requirements for regenerative use. Addressing these limitations will be essential for future development. Expanded studies should incorporate extended implantation timelines, include additional concentrations of L-serine, and conduct mechanical testing. Moreover, evaluation in anatomically relevant models, such as bone-contact or defect-based environments, would provide more meaningful context for potential application-specific performance [

31,

32].