Cationic Surface Modification Combined with Collagen Enhances the Stability and Delivery of Magnetosomes for Tumor Hyperthermia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cultivation of AMB-1 and MTS Extraction

2.3. Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) of AMB-1 and MTS

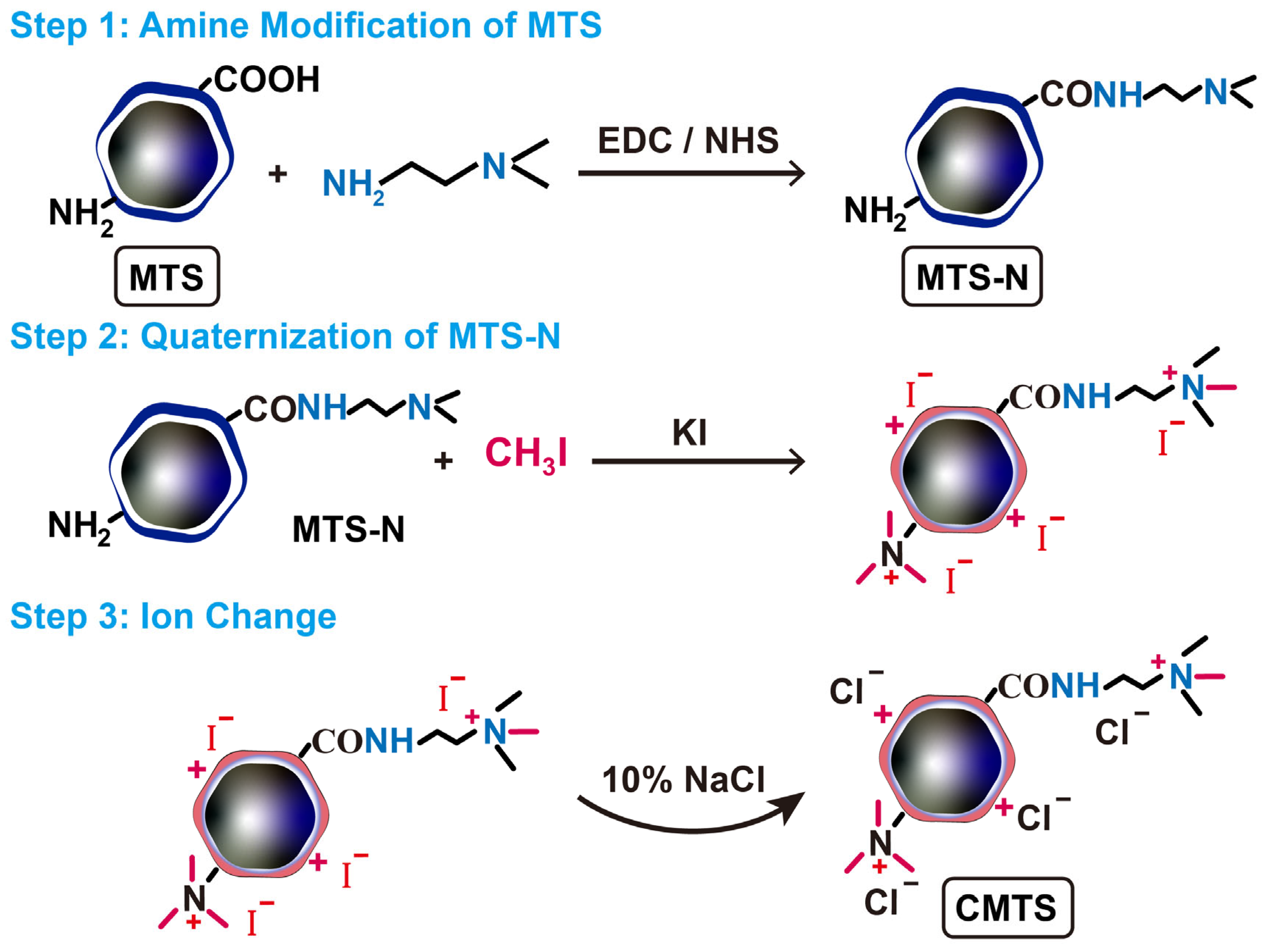

2.4. Preparation of CMTS

2.5. Synthesis of SIONP

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Characterization

2.7. Ninhydrin Reaction

2.8. Measurement of ζ-Potential and Surface Charge Distribution

2.9. Preparation of Magnetic Suspensions

2.10. Suspension Stability Test

2.11. Delivery Performance Evaluation

2.12. Aggregate Size Determination of MTS-Colas and CMTS-Colas

2.13. Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity Evaluation

2.14. Apoptosis and Efficiency Assessment of In Vitro Hyperthermia

2.15. Quantification of CMTS Retained by Tumor Cells

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cultivation of Magnetotactic Bacteria and Extraction of MTS

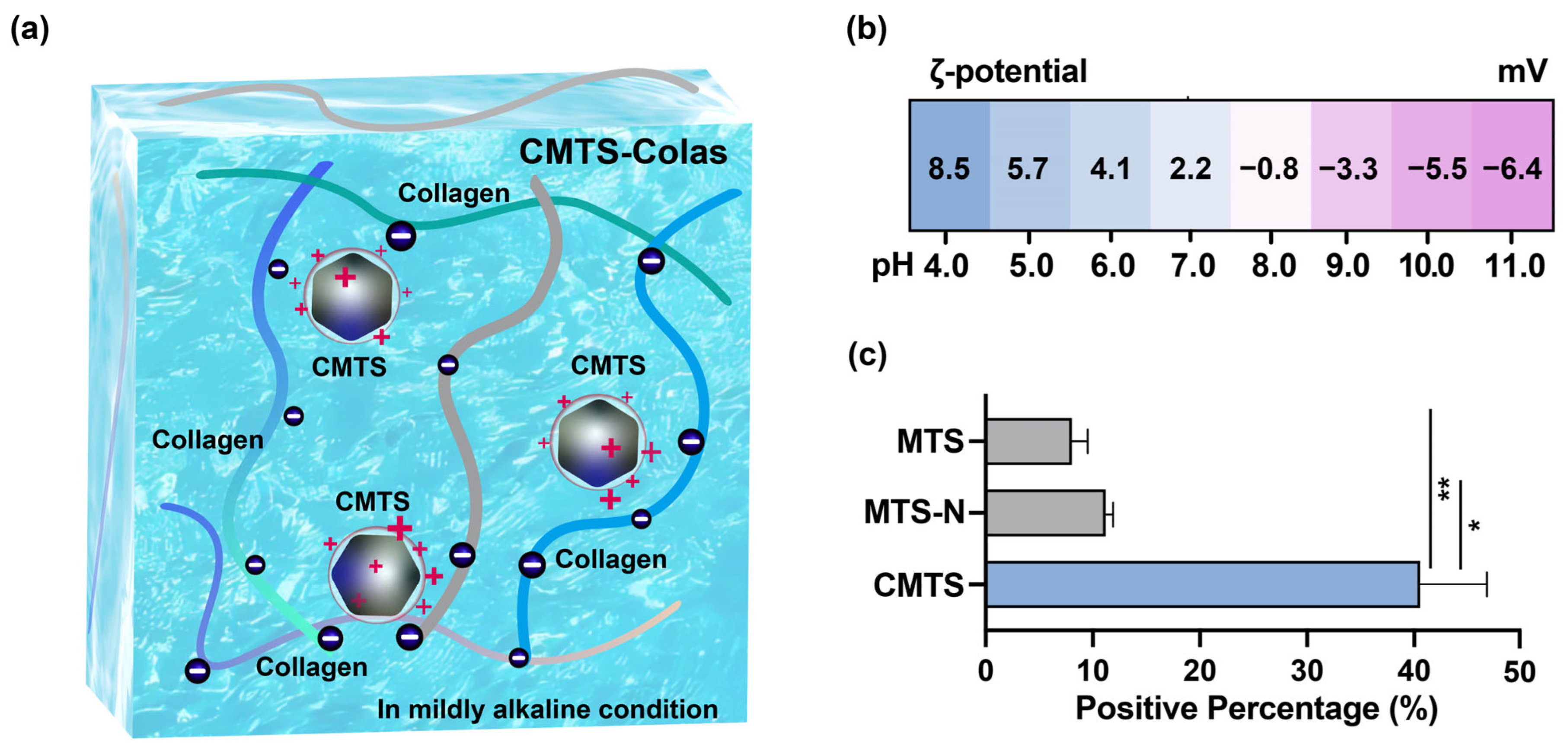

3.2. Characterization of CMTS

3.3. Stabilization Strategy and Preparation for CMTS-Colas

3.4. CMTS-Colas Showed Enhanced Stability at High Concentrations

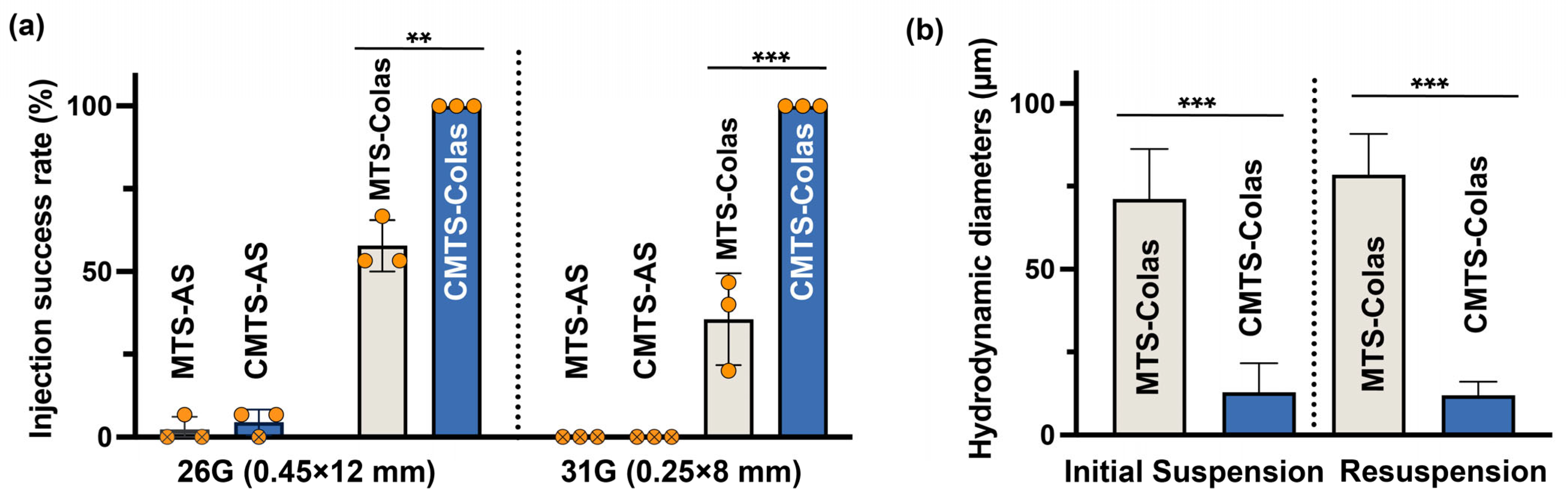

3.5. CMTS-Colas Exhibited Improved Delivery Performance with Fine Needles

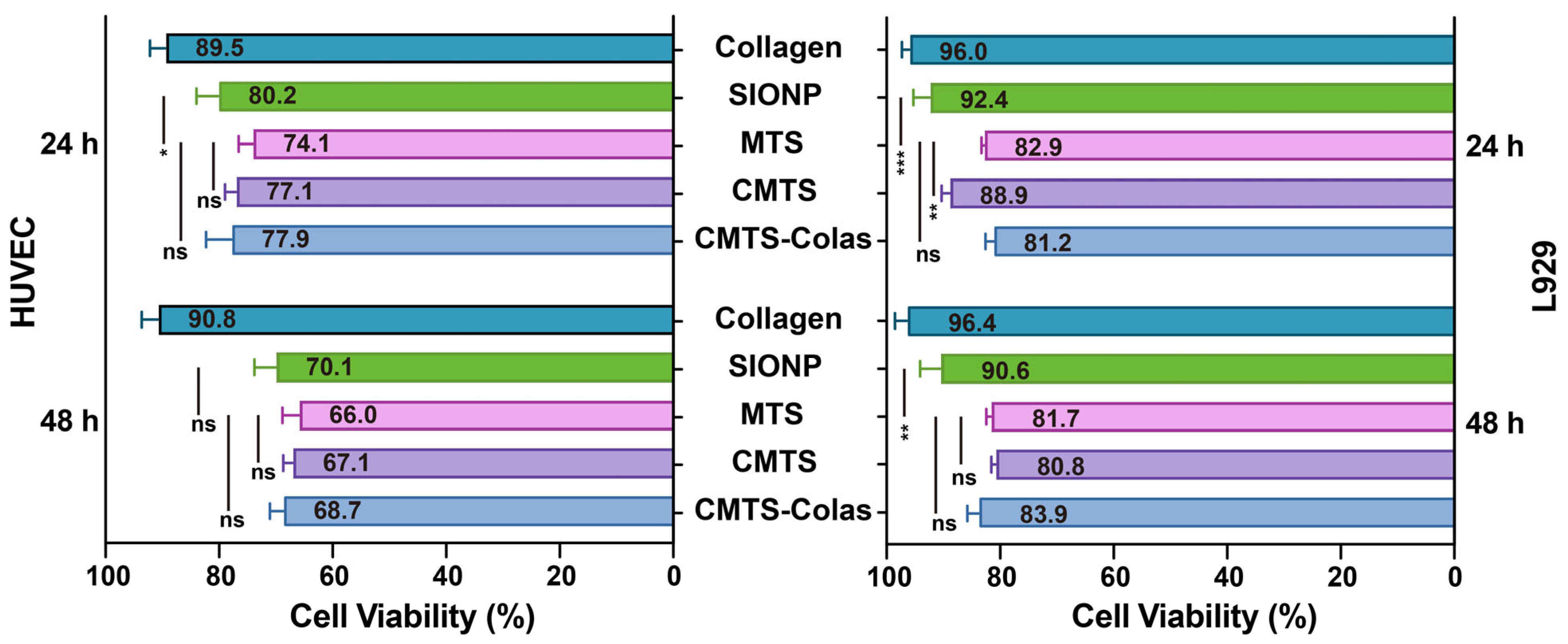

3.6. Cytocompatibility Evaluation of CMTS-Colas and Its Components

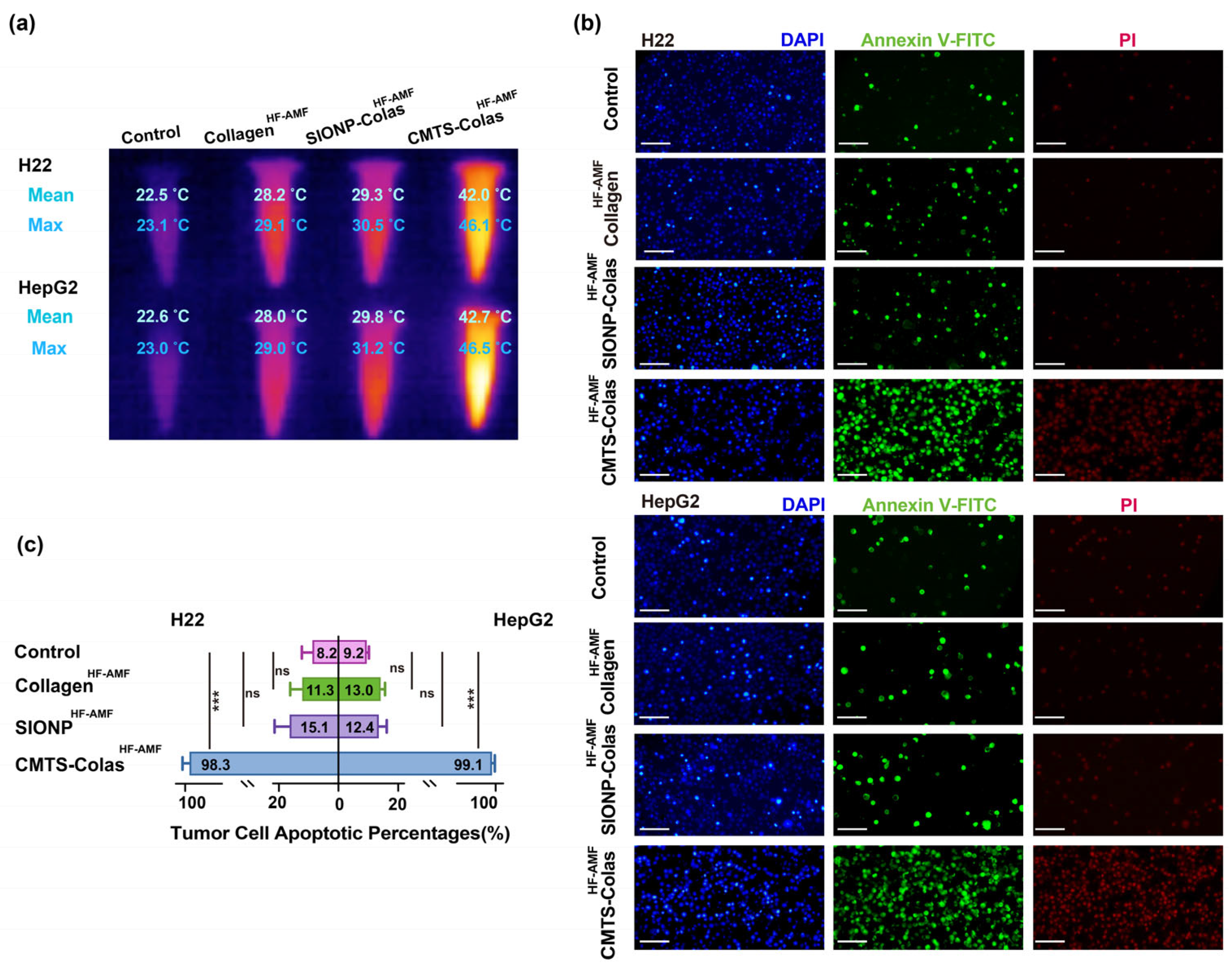

3.7. In Vitro Hyperthermia Performance of CMTS-Colas

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MTS | Magnetosomes |

| CMTS | Cationized magnetosomes |

| CMTS-Colas | Cationized magnetosomes-collagen aqueous suspension |

| MHT | Magnetic hyperthermia therapy |

| HF-AMF | High-frequency alternating magnetic field |

| AMB-1 | Magnetospirillum magneticum strain AMB-1 |

| MTS-N | Amine-modified magnetosomes |

| MTS-AS | Magnetosomes aqueous suspension |

| CMTS-AS | Cationized magnetosomes aqueous suspension |

| SIONP-Colas | SIONP-collagen aqueous suspension |

| MTS-Colas | Magnetosomes-collagen aqueous suspension |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Chebbi, I.; Le Fèvre, R.; Guyot, F.; Alphandéry, E. Non-pyrogenic highly pure magnetosomes for efficient hyperthermia treatment of prostate cancer. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 1159–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, V.; Sundaram, A.; Vasukutty, A.; Bardhan, R.; Uthaman, S.; Park, I.-K. Tumor-targeting cell membrane-coated nanorings for magnetic-hyperthermia-induced tumor ablation. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 7188–7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, B.; Wust, P.; Ahlers, O.; Dieing, A.; Sreenivasa, G.; Kerner, T.; Felix, R.; Riess, H. The cellular and molecular basis of hyperthermia. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2002, 43, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Hou, Z.; Wang, M.; Li, C.; Lin, J. Recent Advances in Hyperthermia Therapy-Based Synergistic Immunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2004788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaque, D.; Martínez Maestro, L.; del Rosal, B.; Haro-Gonzalez, P.; Benayas, A.; Plaza, J.L.; Rodríguez, E.M.; Solé, J.G. Nanoparticles for photothermal therapies. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 9494–9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphandery, E.; Faure, S.; Seksek, O.; Guyot, F.; Chebbi, I. Chains of Magnetosomes Extracted from AMB-1 Magnetotactic Bacteria for Application in Alternative Magnetic Field Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6279–6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanov, V.A.; Kiseleva, A.P.; Krivoshapkina, E.F.; Kashtanov, E.A.; Gimaev, R.R.; Zverev, V.I.; Krivoshapkin, P.V. Synthesis of (Mn(1−x)Znx)Fe2O4 nanoparticles for magnetocaloric applications. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2020, 95, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.P. Ferromagnetic nanoparticles: Synthesis, processing, and characterization. JOM 2010, 62, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, M.; Martella, D.; Barrera, G.; Celegato, F.; Coïsson, M.; Ferrero, R.; Olivetti, E.S.; Troia, A.; Sözeri, H.; Parmeggiani, C.; et al. Improvement of Hyperthermia Properties of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles by Surface Coating. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 2143–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangnier, A.P.; Preveral, S.; Curcio, A.; Silva, A.K.A.; Lefèvre, C.T.; Pignol, D.; Lalatonne, Y.; Wilhelm, C. Targeted thermal therapy with genetically engineered magnetite magnetosomes@RGD: Photothermia is far more efficient than magnetic hyperthermia. J. Control. Release 2018, 279, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Tang, T.; Duan, J.; Xu, P.-X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Li, Y. Biocompatibility of bacterial magnetosomes: Acute toxicity, immunotoxicity and cytotoxicity. Nanotoxicology 2010, 4, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphandéry, E.; Idbaih, A.; Adam, C.; Delattre, J.-Y.; Schmitt, C.; Guyot, F.; Chebbi, I. Development of non-pyrogenic magnetosome minerals coated with poly-l-lysine leading to full disappearance of intracranial U87-Luc glioblastoma in 100% of treated mice using magnetic hyperthermia. Biomaterials 2017, 141, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Teng, Y.; Tian, J.; Hu, Z.; Fang, Q. A comprehensive assessment of the biocompatibility of Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense MSR-1 bacterial magnetosomes in vitro and in vivo. Toxicology 2021, 462, 152949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorzewski, J.; Michalak, M.; Wołoszczuk, M.; Bulicz, M.; Majchrzak-Celińska, A. Nanotherapy of Glioblastoma—Where Hope Grows. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mickoleit, F.; Jörke, C.; Richter, R.; Rosenfeldt, S.; Markert, S.; Rehberg, I.; Schenk, A.S.; Bäumchen, O.; Schüler, D.; Clement, J.H. Long-Term Stability, Biocompatibility, and Magnetization of Suspensions of Isolated Bacterial Magnetosomes. Small 2023, 19, e2206244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Cui, H.; Huang, Y.; Qin, S. High-yield magnetosome production of Magnetospirillum magneticum strain AMB-1 in flask fermentation through simplified processing and optimized iron supplementation. Biotechnol. Lett. 2024, 46, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorby, Y.A.; Beveridge, T.J.; Blakemore, R.P. Characterization of the bacterial magnetosome membrane. J. Bacteriol. 1988, 170, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grünberg, K.; Müller, E.-C.; Otto, A.; Reszka, R.; Linder, D.; Kube, M.; Reinhardt, R.; Schüler, D. Biochemical and Proteomic Analysis of the Magnetosome Membrane in Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1040–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alphandéry, E. Applications of magnetotactic bacteria and magnetosome for cancer treatment: A review emphasizing on practical and mechanistic aspects. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, J.J.; Suthindhiran, K. Efficiency of Immobilized Enzymes on Bacterial Magnetosomes. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2021, 57, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguraman, V.; Jayasri, M.A.; Suthindhiran, K. Magnetosome mediated oral Insulin delivery and its possible use in diabetes management. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2020, 31, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.-H.; Perevedentseva, E.; Tu, J.-S.; Chang, C.; Cheng, C.-L. Spectroscopic study of bio-functionalized nanodiamonds. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2006, 15, 622–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Guo, Z.; Jiang, A.; Liang, X.; Tan, W. Cationic Chitooligosaccharide Derivatives Bearing Pyridinium and Trialkyl Ammonium: Preparation, Characterization and Antimicrobial Activities. Polymers 2023, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Cai, C.; Wu, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Feng, Z.; He, N.; Wang, T. Preservative for High Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity and Low Toxicity. Langmuir 2024, 40, 26055–26066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.K. An Insight into Collagen-Based Nano Biomaterials for Drug Delivery Applications. In Engineered Biomaterials: Synthesis and Applications; Malviya, R., Sundram, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 397–428. [Google Scholar]

- Kalska-Szostko, B.; Wykowska, U.; Piekut, K.; Satuła, D. Stability of Fe3O4 nanoparticles in various model solutions. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 450, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoń, A.; Łoński, S.; Kądziołka-Gaweł, M.; Gębara, P.; Lis, M.; Łukowiec, D.; Babilas, R. Influence of magnetite nanoparticles surface dissolution, stabilization and functionalization by malonic acid on the catalytic activity, magnetic and electrical properties. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 607, 125446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberdeen, S.; Hur, C.A.; Cali, E.; Vandeperre, L.; Ryan, M. Acid resistant functionalised magnetic nanoparticles for radionuclide and heavy metal adsorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 608, 1728–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruppathi, K.P.; Nataraj, D. Phase transformation from α-Fe2O3 to Fe3O4 and LiFeO2 by the self-reduction of Fe(iii) in Prussian red in the presence of alkali hydroxides: Investigation of the phase dependent morphological and magnetic properties. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 6170–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Yan, H.; Jiao, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Gu, Y.; Gang, F.; et al. Effect of OH− concentration on Fe3O4 nanoparticle morphologies supported by first principle calculation. J. Cryst. Growth 2020, 547, 125780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.A. Simulation and experimental study of cuboid and spherical magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles prepared with NaOH and NH4OH. Appl. Phys. A 2023, 129, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdous, Y.; Chebbi, I.; Mandawala, C.; Le Fèvre, R.; Guyot, F.; Seksek, O.; Alphandéry, E. Biocompatible coated magnetosome minerals with various organization and cellular interaction properties induce cytotoxicity towards RG-2 and GL-261 glioma cells in the presence of an alternating magnetic field. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 15, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhou, X.; Long, R.; Xie, M.; Kankala, R.K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.S.; Liu, Y. Biomedical applications of magnetosomes: State of the art and perspectives. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 28, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yan, X.; Chen, S.; Du, Y.; Hu, J.; Song, Y.; Zha, Z.; Xu, Y.; Cao, B.; Xuan, S.; et al. Minimally Invasive Delivery of Percutaneous Ablation Agent via Magnetic Colloidal Hydrogel Injection for Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2309770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usov, N.A.; Gubanova, E.M. Application of Magnetosomes in Magnetic Hyperthermia. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, K.; Bouras, A.; Bozec, D.; Ivkov, R.; Hadjipanayis, C. Magnetic hyperthermia therapy for the treatment of glioblastoma: A review of the therapy’s history, efficacy and application in humans. Int. J. Hyperth. 2018, 34, 1316–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, D.; Schupper, A.J.; Bouras, A.; Anastasiadou, M.; Kleinberg, L.; Kraitchman, D.L.; Attaluri, A.; Ivkov, R.; Hadjipanayis, C.G. Neurosurgical Applications of Magnetic Hyperthermia Therapy. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 34, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, B.S.; Schnellmann, R.G. Measurement of Cell Death in Mammalian Cells. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Cui, H.; Li, B.; Liu, Z.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; et al. Cationic Surface Modification Combined with Collagen Enhances the Stability and Delivery of Magnetosomes for Tumor Hyperthermia. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120461

Wang Y, Lin C, Zhang Y, Li W, Cui H, Li B, Liu Z, Wang K, Wang Q, Wang Y, et al. Cationic Surface Modification Combined with Collagen Enhances the Stability and Delivery of Magnetosomes for Tumor Hyperthermia. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2025; 16(12):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120461

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yu, Conghao Lin, Yubing Zhang, Wenjun Li, Hongli Cui, Bohan Li, Zhengyi Liu, Kang Wang, Qi Wang, Yinchu Wang, and et al. 2025. "Cationic Surface Modification Combined with Collagen Enhances the Stability and Delivery of Magnetosomes for Tumor Hyperthermia" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 16, no. 12: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120461

APA StyleWang, Y., Lin, C., Zhang, Y., Li, W., Cui, H., Li, B., Liu, Z., Wang, K., Wang, Q., Wang, Y., Lv, K., Huang, Y., Zhuang, H., & Qin, S. (2025). Cationic Surface Modification Combined with Collagen Enhances the Stability and Delivery of Magnetosomes for Tumor Hyperthermia. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 16(12), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120461