1. Introduction

Learning a second or foreign language is not merely a linguistic endeavor but a cognitively demanding and emotionally dynamic process that requires sustained regulation of attention, effort, and affective states. In English-as-a-second-language (ESL) contexts, learners must cope with high cognitive load, competitive assessments, and limited opportunities for authentic communication, all of which contribute to heightened emotional strain and motivational fluctuations (

Dörnyei and Ryan 2015;

Li et al. 2025). While traditional research in second language acquisition (SLA) has primarily emphasized cognitive and linguistic predictors of success, an increasing body of work has recognized that non-cognitive factors—such as emotions, perseverance, and motivation—play equally crucial roles in shaping learning trajectories (

MacIntyre and Gregersen 2012). However, despite this growing attention, existing studies often examine these factors in isolation, leaving unclear how emotional and motivational processes interact to influence sustained language learning performance. Addressing this gap requires a theoretically integrated model that elucidates emotional competence, effortful persistence, and motivational engagement within a coherent explanatory framework.

Among these non-cognitive factors, emotional intelligence (EI) has emerged as a key construct in applied linguistics and educational psychology. Defined by

Salovey and Mayer (

1990) as the ability to perceive, understand, regulate, and utilize emotions in oneself and others, EI has been conceptualized under two major frameworks: ability EI, which reflects actual emotional problem-solving abilities measured through performance-based tasks, and trait EI, which represents individuals’ self-perceived emotional efficacy and dispositions, typically assessed through self-report questionnaires (

Pérez et al. 2005;

Petrides and Furnham 2000). The present study adopts the trait EI perspective and employs the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS;

Wong and Law 2002), a validated self-report measure widely used in educational settings. This choice aligns with the study’s focus on learners’ perceived emotional regulation and self-appraisal abilities as predictors of motivation and performance—domains that are best captured through subjective emotional awareness rather than objective ability testing. This conceptualization follows the methodological distinctions outlined by

Petrides and Furnham (

2000) and

Joseph and Newman (

2010), who emphasized that trait EI reflects affective self-perceptions integrated within personality hierarchies, whereas ability EI captures maximal performance on emotion-related cognitive tasks. Empirical evidence has consistently shown that higher trait EI is associated with reduced language anxiety, stronger self-regulation, and enhanced academic achievement (

Dewaele 2019;

Li et al. 2024;

Jin et al. 2024). These findings suggest that learners’ emotional competencies not only influence how they experience the affective dimension of language learning but also shape the motivational processes that sustain their engagement over time.

Another important set of constructs that bridge emotion and achievement are L2 grit and L2 motivation. Grit, defined as the perseverance and sustained passion for long-term language learning goals (

Duckworth et al. 2007;

Teimouri et al. 2022), enables learners to maintain consistent effort despite setbacks and fluctuations in external reinforcement. Motivation, on the other hand, reflects the goal-directed energy that activates and sustains engagement in learning (

Dörnyei 2005;

Ryan and Deci 2000). Although both constructs are positively correlated, research suggests that grit and motivation operate at different temporal and functional levels: grit reflects the endurance to persist, whereas motivation captures the dynamic intensity of engagement at a given moment (

Credé et al. 2017;

Datu et al. 2016). Emotionally intelligent learners—who can accurately perceive and regulate emotions—are more likely to maintain a sense of control and positive value toward learning tasks, thereby enhancing perseverance (grit) and then sustaining motivation (

Gao 2025;

Chang and Tsai 2022).

The Control–Value Theory (

Pekrun 2006;

Pekrun and Perry 2014) provides a theoretical rationale for this sequence, positing that emotions influence learners’ perceived control and value appraisals, which in turn sustain perseverance (grit) and fuel motivation. From this perspective, emotionally intelligent learners are better able to regulate negative emotions such as anxiety and to maintain long-term commitment, which subsequently reinforces motivational intensity and engagement (

Teimouri et al. 2022;

Gao 2025). The L2 Motivational Self System (

Dörnyei 2009) similarly supports this temporal ordering, as the ability to persevere toward one’s ideal L2 self-fosters sustained motivation to achieve it. Therefore, in the present study, grit is conceptualized as a precursor of motivation, representing the self-regulatory stamina that enables learners to translate emotional resources into enduring motivational engagement over time. EI may not only exert direct effects on language performance but also indirectly influence achievement through the sequential pathway of grit and motivation.

However, while previous studies have separately examined the effects of EI, grit, and motivation on language outcomes, few have empirically tested their combined mediating mechanisms within a single model, particularly in the Chinese ESL context (

Peng and Li 2025). To address this gap, the present study investigates how Chinese ESL learners’ emotional intelligence (EI) relates to their language learning performance through the sequential mediation of L2 grit and L2 motivation. By integrating these three constructs into a chain mediation framework, the study aims to clarify the emotional–motivational mechanisms that underlie language achievement. Specifically, this research makes three verifiable contributions. Firstly, at the theoretical level, it extends the application of the Control–Value Theory (

Pekrun 2006) and L2 Motivational Self System (

Dörnyei 2009) by empirically testing a novel causal sequence—EI → grit → motivation → performance—thereby demonstrating how emotional regulation capacities can sustain perseverance and, in turn, reinforce motivational engagement. Secondly, at the methodological level, it adopts a large-scale SEM design (N = 801) with second-order and parcel-based modeling, using both questionnaire data and standardized CET-4 performance scores, which enhances measurement reliability and external validity. Thirdly, at the applied level, the study offers pedagogical insights for fostering emotionally intelligent, persistent, and motivated learners in high-stakes ESL contexts by suggesting classroom practices that integrate socio-emotional learning with goal-oriented instruction. These contributions provide a more comprehensive understanding of how emotional and motivational resources interact to shape successful second-language learning.

5. Discussion

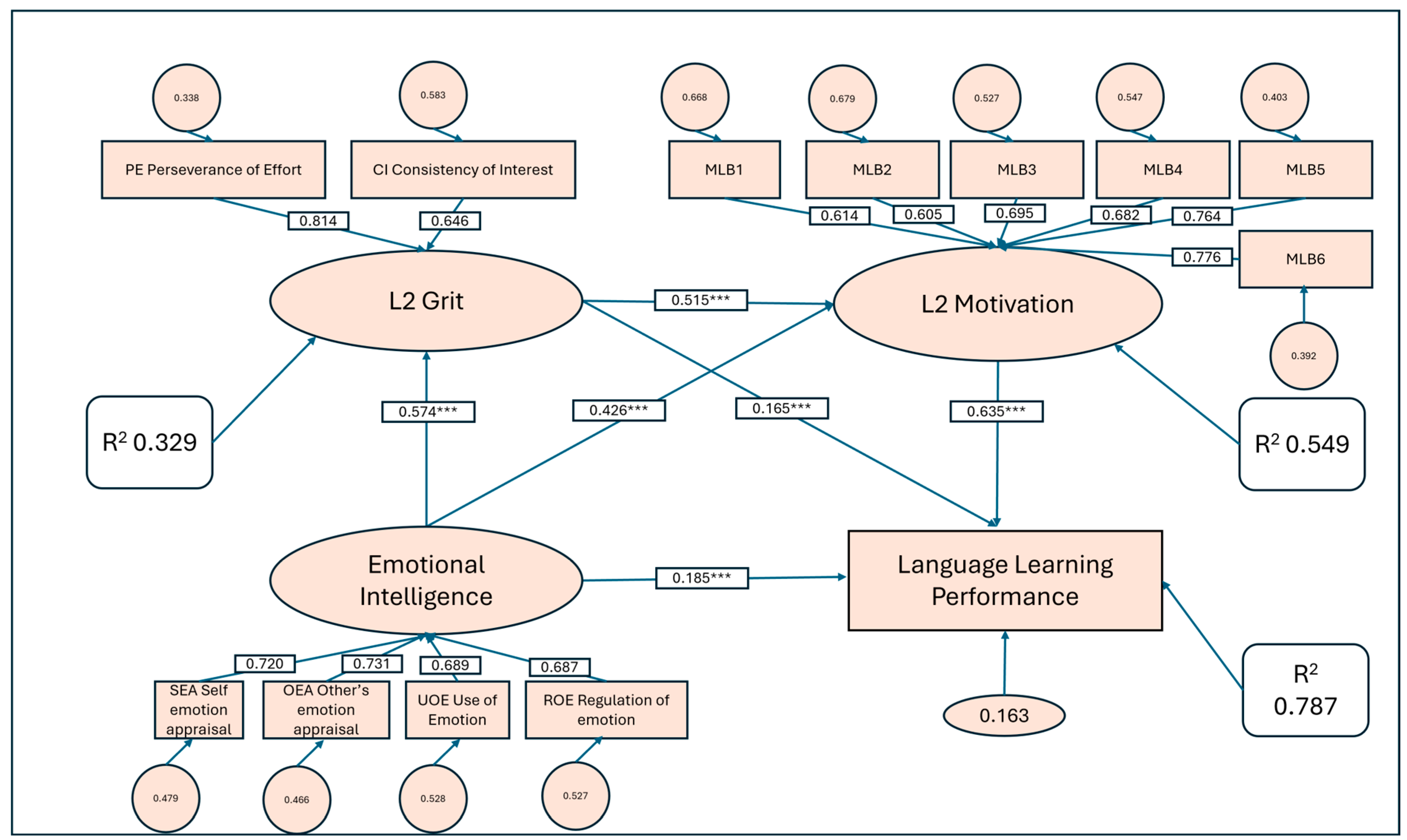

The hypothesized model revealed several significant associations among emotional intelligence (EI), grit, motivation, and performance (

Table 7). EI was positively associated with grit (β = 0.574, SE = 0.036, z = 15.800,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.503, 0.645]) and motivation (β = 0.426, SE = 0.043, z = 10.016,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.343, 0.510]). Grit was also strongly correlated with motivation (β = 0.515, SE = 0.043, z = 11.919,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.430, 0.599]). In relation to performance, motivation (β = 0.635, SE = 0.049, z = 12.916,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.539, 0.732]), EI (β = 0.185, SE = 0.034, z = 5.432,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.118, 0.251]), and grit (β = 0.165, SE = 0.041, z = 4.026,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.085, 0.246]) all showed significant positive relations with the outcome.

Bootstrap analysis further revealed robust indirect associations (

Table 8). EI was indirectly related to performance through grit (β = 0.095, SE = 0.025, z = 3.781,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.048, 0.149]), through motivation (β = 0.271, SE = 0.039, z = 7.008,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.199, 0.350]), and via the sequential path EI–grit–motivation–performance (β = 0.188, SE = 0.026, z = 7.326,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.140, 0.241]). The total indirect association was β = 0.553 (SE = 0.039, z = 14.048,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.476, 0.628]), and the total association between EI and performance reached β = 0.738 (SE = 0.033, z = 22.423,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.669, 0.805]). Collectively, these findings indicate that EI, grit, and motivation were closely interrelated, with both direct and indirect links to performance, underscoring the strong interconnectedness among the four constructs.

The findings of this study are consistent with Hypothesis 1, showing that emotional intelligence (EI) is positively associated with language learning performance (β = 0.185,

p < .001). This result indicates that learners with higher levels of EI tend to achieve better academic outcomes in English as a second language. The direct effect of EI on performance aligns with previous research emphasizing the crucial role of emotional competencies in academic success. For instance,

MacCann et al. (

2020) found that EI predicted achievement above and beyond cognitive ability and personality, while

Li and Xu (

2019) reported that students with stronger emotion regulation and appraisal skills were better able to cope with language learning anxiety and sustain effort, thereby achieving higher levels of performance. Similar conclusions were drawn by

Petrides et al. (

2004) and

Perera and DiGiacomo (

2013), who highlighted EI as a predictor of both academic engagement and achievement. At the same time, the present findings differ from some earlier studies where EI’s influence on performance was found to be mostly indirect, mediated by motivational or affective variables (

Dewaele 2019). One explanation for this discrepancy may be methodological. Whereas prior studies often modeled EI’s effects indirectly through mediators such as motivation, the present study employed a parcel-based SEM approach, which reduces measurement error and allows for more reliable estimation of direct paths (

Little et al. 2002). This approach may have revealed a stronger direct effect of EI on performance than previously observed. These results suggest that EI is not only a distal resource that operates through mediating mechanisms such as grit and motivation but also a proximal predictor of achievement. Learners who can effectively perceive, regulate, and use emotions may directly channel these capacities into improved focus, resilience, and learning strategies, thereby enhancing their language learning performance (

Mayer and Salovey 1997;

Pekrun 2006).

The results are consistent with Hypothesis 2, indicating that L2 grit significantly mediated the relationship between EI and language learning performance. From a correlational standpoint, emotional intelligence (EI) showed a strong positive association with grit (β = 0.574, SE = 0.036, z = 15.800,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.503, 0.645]), and grit was in turn positively related to performance (β = 0.165, SE = 0.041, z = 4.026,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.085, 0.246]). Bootstrap results indicated a significant indirect association between EI and performance through grit (β = 0.095, SE = 0.025, z = 3.781,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.048, 0.149]), suggesting that individuals with higher EI also tended to report higher grit levels, which were in turn associated with stronger performance outcomes, confirming the mediating role of grit. This finding is consistent with prior studies emphasizing the role of grit in academic achievement and its links to socio-emotional resources. For instance,

Duckworth et al. (

2007) originally conceptualized grit as perseverance and passion for long-term goals, and subsequent work has shown its predictive validity for academic success across diverse contexts (

Credé et al. 2017). Within the domain of language learning,

Teimouri et al. (

2019) and

Wei et al. (

2019) demonstrated that L2 grit predicted language proficiency and persistence in learning, while

Sudina and Plonsky (

2021) noted that learners with stronger emotional and motivational regulation tend to maintain higher levels of perseverance. The present study extends this body of work by providing evidence that EI functions as an antecedent of L2 grit, highlighting the pathway through which emotional competencies facilitate sustained effort and resilience in second-language learning. In line with socio-emotional theories of learning (

Mayer and Salovey 1997;

Pekrun 2006), learners who can effectively perceive, regulate, and utilize their emotions are more likely to persevere despite difficulties, which in turn enhances academic outcomes.

The findings are also consistent with Hypothesis 3, showing that L2 motivation mediated the relationship between EI and performance. From a correlational perspective, emotional intelligence (EI) was positively associated with motivation (β = 0.426, SE = 0.043, z = 10.016,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.343, 0.510]), and motivation was in turn strongly related to performance (β = 0.635, SE = 0.049, z = 12.916,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.539, 0.732]). Bootstrap analysis indicated a significant indirect association and mediation between EI and performance through motivation (β = 0.271, SE = 0.039, z = 7.008,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.199, 0.350]). These results suggest that individuals with higher emotional intelligence also tended to report greater motivation, which was closely linked with higher performance outcomes. These results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that emotionally intelligent learners tend to sustain higher levels of motivation in language learning (

Dewaele and Li 2020;

Gardner 2010;

Papi and Khajavy 2021). Learners who can effectively regulate emotions are better able to maintain interest, exert effort, and remain engaged in learning tasks, which translates into stronger performance (

Dörnyei and Ushioda 2011;

Pekrun 2006). The findings also align with expectancy-value theory (

Eccles and Wigfield 2002) and self-determination theory (

Ryan and Deci 2000), both of which posit that motivational engagement serves as a key mechanism through which personal traits influence academic outcomes.

The results are consistent with Hypothesis 4, which proposed a sequential mediation pathway from EI to performance through L2 grit and L2 motivation. From a correlational standpoint, emotional intelligence (EI), grit, motivation, and performance were strongly interconnected through a sequential pattern. EI was positively associated with grit (β = 0.574,

p < .001), grit was positively related to motivation (β = 0.515,

p < .001), and motivation, in turn, was positively linked with performance (β = 0.635,

p < .001). The sequential indirect association following the chain EI → grit → motivation → performance was statistically significant (β = 0.188, SE = 0.026, z = 7.326,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.140, 0.241]). This pattern indicates that higher emotional intelligence tended to co-occur with greater grit and motivation, which together were associated with higher performance, highlighting a coherent chain of associations among the constructs. This finding is consistent with theoretical frameworks positing that socio-emotional competencies affect achievement indirectly through motivational processes (

Pekrun 2006). Prior research has shown that learners high in EI are more likely to persist in the face of difficulties (

Mayer and Salovey 1997;

MacCann et al. 2020), which reflects higher levels of grit (

Duckworth et al. 2007;

Teimouri et al. 2022). In turn, grit has been found to sustain motivation over time by supporting learners’ ability to maintain interest and invest effort in language learning (

Wei et al. 2019;

Sudina and Plonsky 2021). Motivation itself has long been identified as a proximal driver of achievement in second language acquisition (

Dörnyei 2005;

Papi and Khajavy 2021), serving as the immediate mechanism through which persistence and engagement are translated into performance gains. Compared with earlier studies that typically examined either the EI–motivation–achievement pathway (

Dewaele and Li 2020;

MacCann et al. 2020) or the grit–achievement link in isolation (

Teimouri et al. 2022), the present study demonstrates the added value of considering grit and motivation together in a sequential model. By integrating these two mediators, the findings highlight how EI not only initiates perseverance but also channels this perseverance into sustained motivational energy, which then enhances academic performance. The strong explanatory power of the sequential mediation model (

R2 = 0.787 for performance) further underscores the robustness of this pathway.

From a pedagogical perspective, the findings suggest that interventions targeting emotional intelligence may indirectly improve learners’ perseverance, motivation, and, ultimately, language achievement. Teachers can integrate socio-emotional learning activities into the curriculum, such as reflective tasks, emotion regulation strategies, and collaborative exercises that promote empathy and interpersonal awareness. Furthermore, supporting students in setting long-term learning goals and reinforcing consistent effort can strengthen grit, which, in turn, fuels motivation. Institutional policies that recognize the role of socio-emotional development in language learning could also enhance student engagement and persistence.

5.1. Implications

From a theoretical perspective, this study extends the Control–Value Theory (

Pekrun 2006) by clarifying how emotional intelligence (EI) influences language learning performance through L2 grit and motivation. The findings indicate that EI provides learners with the emotional regulation and perceived control necessary to sustain long-term learning efforts and value their academic goals, which, in turn, facilitates motivational engagement and perseverance. This integrated emotional–motivational model highlights the interconnected nature of affective and volitional factors in shaping second language achievement and offers an expanded framework for understanding individual differences in L2 learning.

From a pedagogical perspective, the results provide actionable guidance for language educators seeking to foster socio-emotional and motivational growth among learners. Firstly, teachers should actively cultivate learners’ emotional intelligence by integrating socio-emotional learning (SEL) into daily instruction. This may include reflective journaling on emotional experiences in language learning, role-play and storytelling tasks that develop empathy and emotional awareness, and guided discussions on how to manage frustration and anxiety during language use. Secondly, to strengthen L2 grit, educators should help students set specific and attainable learning goals, monitor their own progress, and celebrate incremental achievements to reinforce self-efficacy. Incorporating materials and activities that connect with learners’ personal interests, lived experiences, and cultural backgrounds can also sustain engagement and long-term commitment to language learning. Thirdly, enhancing L2 motivation requires creating a supportive and autonomy-oriented classroom environment. Teachers can offer meaningful choices in learning activities, connect lessons to real-world communicative purposes, and provide opportunities for goal reflection to strengthen intrinsic motivation. Finally, given the variability in students’ emotional intelligence, grit, and motivation, teachers should adopt differentiated instruction and personalized feedback strategies to address individual differences effectively.

At the institutional level, curriculum designers and administrators should recognize socio-emotional competencies as foundational to successful L2 learning. Embedding emotion regulation, perseverance, and motivational training into teacher development programs and assessment frameworks can cultivate classrooms where learners are not only linguistically competent but also emotionally resilient and self-motivated.

In addition, the present findings point to promising but as yet untested avenues for intervention. Future research could design pilot EI-based training programs, such as emotional regulation workshops, mindfulness and empathy sessions, or self-reflective emotional awareness activities, followed by systematic evaluation of changes in learners’ motivation and performance. These interventions could be tested through experimental or quasi-experimental designs using pre–post assessments and control groups to determine whether improvements in emotional intelligence correspond to increases in motivation and achievement. Researchers should also account for potential covariates, including learners’ cognitive ability, prior proficiency, and institutional support, to isolate the specific effects of socio-emotional training. Such pilot programs would offer empirical evidence for the causal direction of the observed associations and guide the development of sustainable, evidence-based emotional intelligence interventions in language education.

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that warrant caution. Firstly, the use of self-report questionnaires for EI, grit, and motivation may introduce common method bias and social desirability effects. Although structural modeling helped address measurement error, future research could benefit from incorporating multi-method assessments, such as teacher ratings or behavioral indicators. Secondly, the cross-sectional nature of this study limits the ability to draw causal conclusions regarding the relationships among emotional intelligence, grit, motivation, and performance. Although the observed associations are consistent with the hypothesized sequential pattern, the temporal order of these variables cannot be verified within a single time point. Thirdly, performance was measured using a standardized test, which may not fully capture learners’ communicative competence or real-world language use. Fourthly, although the present study, like many other studies (

Li et al. 2021;

Sudina et al. 2021;

Sudina and Plonsky 2021), focused on emotional and motivational predictors, future research should integrate cognitive ability measures or contextual support measures to more comprehensively capture the control–value dynamics underlying language learning outcomes. Cognitive abilities such as working memory, attentional control, and reasoning capacity form the cognitive foundation upon which emotional and motivational processes operate. Fifthly, while item parceling was adopted to enhance model stability and reduce random measurement error, it may also obscure within-construct variability and lead to overestimation of reliability or model fit. Future research should re-estimate models using item-level indicators or conduct sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of parcel-based results. Finally, the sample was drawn from a single cultural and educational context in China, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings to other L2 learning populations.

Building on these limitations, future research could explore several promising directions. Future studies should employ longitudinal designs to examine how these constructs evolve and influence one another over time, or experimental/intervention-based approaches to establish directional effects more rigorously. Intervention studies could test whether explicit training in emotional intelligence or perseverance strategies leads to measurable gains in motivation and performance. Expanding the scope of performance measures to include cognitive abilities, communicative competence, classroom participation, or teacher assessments may provide a more comprehensive understanding of outcomes. Furthermore, cross-cultural comparisons could reveal whether the observed mediation mechanisms hold across diverse educational systems and cultural contexts. Future research could also further explore potential gender differences in the emotional–motivational mechanisms underlying language learning. Given prior evidence that females often demonstrate higher levels of emotional intelligence and empathy (

Cabello et al. 2016), a multi-group structural equation modeling (SEM) approach could be employed to compare whether the structural relations among EI, grit, motivation, and performance differ across male and female learners. Such analysis would provide valuable insights into gender-specific pathways of emotional and motivational functioning in second language learning. Finally, integrating additional socio-emotional constructs—such as foreign language enjoyment, anxiety, or resilience—could enrich theoretical models and offer a more complete picture of the emotional-motivational landscape in second language acquisition.