The Health-Wealth Gradient in Labor Markets: Integrating Health, Insurance, and Social Metrics to Predict Employment Density

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Objectives

- 1.

- Construct a Multi-Source Longitudinal Dataset: The dataset combines economic data with public health information which includes but is not limited to obesity rates and violent crime statistics and housing problems throughout all states from 2014 to 2024.

- 2.

- Create a forecasting pipeline based on regularized XGBoost: The research implements a time-dependent train–test split to evaluate multiple predictive models, including LASSO regression and Random Forest and regularized XGBoost with a focus on how well they perform in real-world scenarios. The Ridge ensemble model operates in stacked mode to verify if uniting different model types produces better results than the top-performing non-linear model.

- 3.

- Examine selected feature importance for reasonableness through case study: Analyze some of the most predictive variables in Texas and New Jersey and interpret the results based on their respective characteristics. Pinpoint that the model result can help identify state-specific risk profiles, which supports strategic monitoring and sheds light on hypotheses for future causal research.

1.2. Contributions

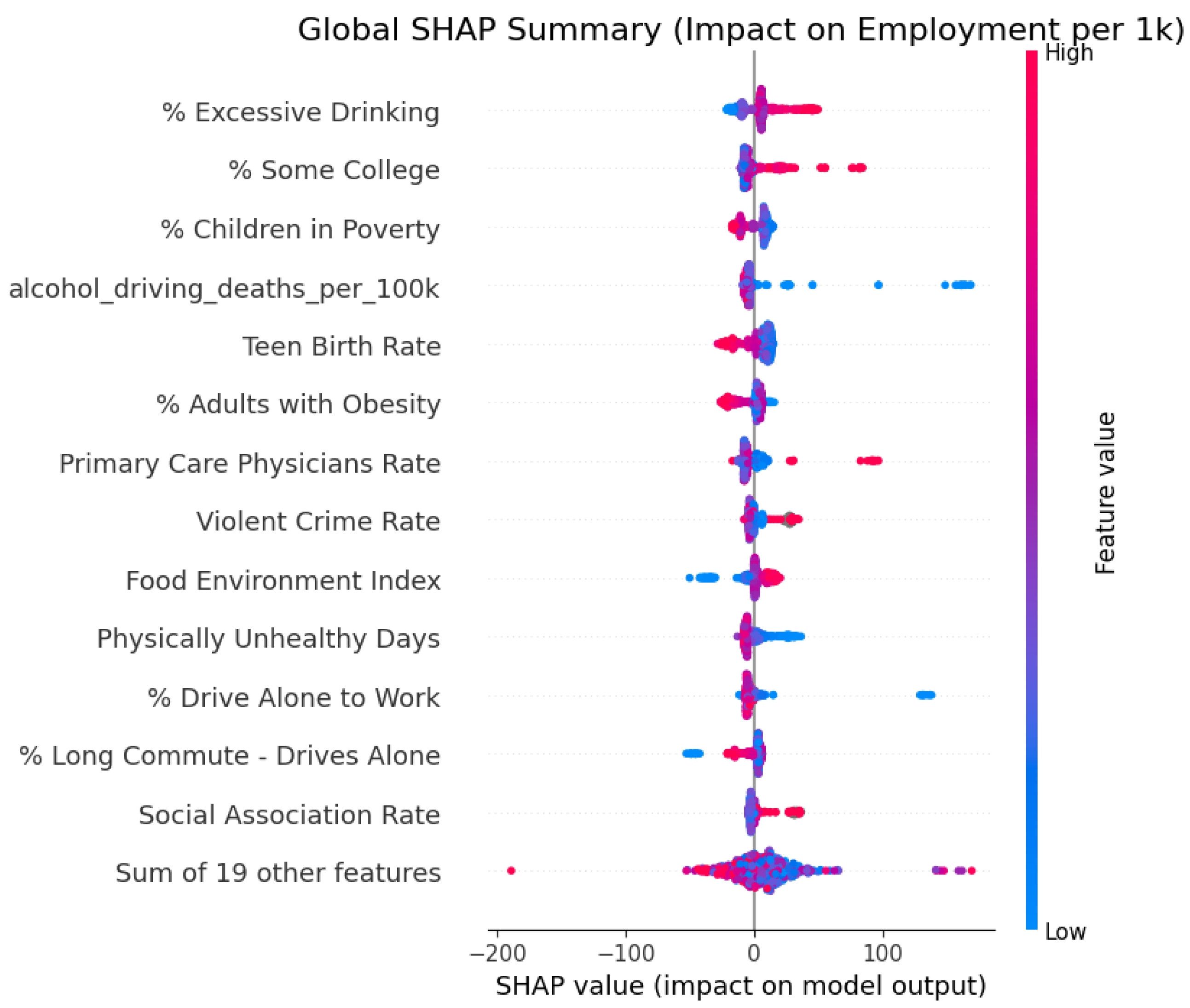

- The research establishes a single-model inference which connects predictive accuracy to economic interpretations at different scales. The XGBoost model with regularization and diagnostic functions is used to analyze data at different levels of detail. The national level reveals the hierarchical structure of health and social determinants which affect employment density according to SHAP values. The state-level analysis uses mean SHAP contribution to identify essential variables which contribute most significantly to the predictions along with their directional associations. The stacked Ridge ensemble serves as a robustness checking device which demonstrates that adding more model layers does not improve predictions beyond what the regularized XGBoost model achieves.

- Feature importance ranking together with SHAP analysis helps to establish specific positions for non-economic factors in the “Health–Wealth” relationship. The study advances from qualitative link identification to find specific numerical values which demonstrate % Excessive Drinking and % Some College outperform conventional metrics for employment density prediction.

- By identifying specific, modifiable social determinants (such as housing instability and violent crime) as leading indicators for employment, this research offers policymakers a targeted framework. It suggests that public health and urban safety interventions work as effective indirect financial tools which create employment density growth in various labor market segments.

2. Data Sources and Preparation

2.1. Labor Market and Health Data

2.2. Unit of Analysis and Outcome Variable

2.3. Construction of State-Level Predictors

3. Exploratory Data Analysis: Feature Validation and Spatiotemporal Dynamics

3.1. Temporal Robustness and Structural Divergence

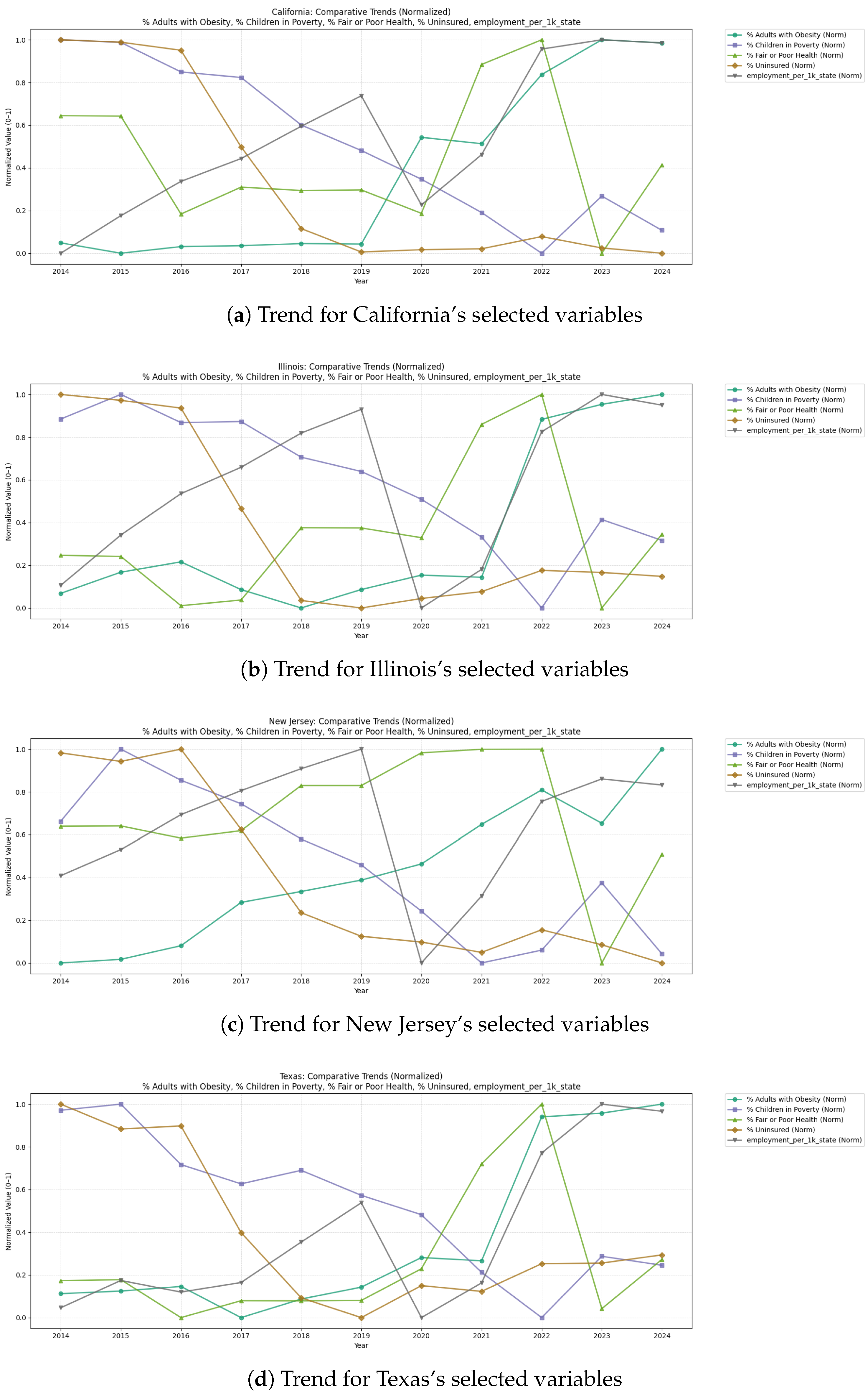

3.1.1. The 2020 Break and Health Independence

3.1.2. Policy Variance and Economic Structure

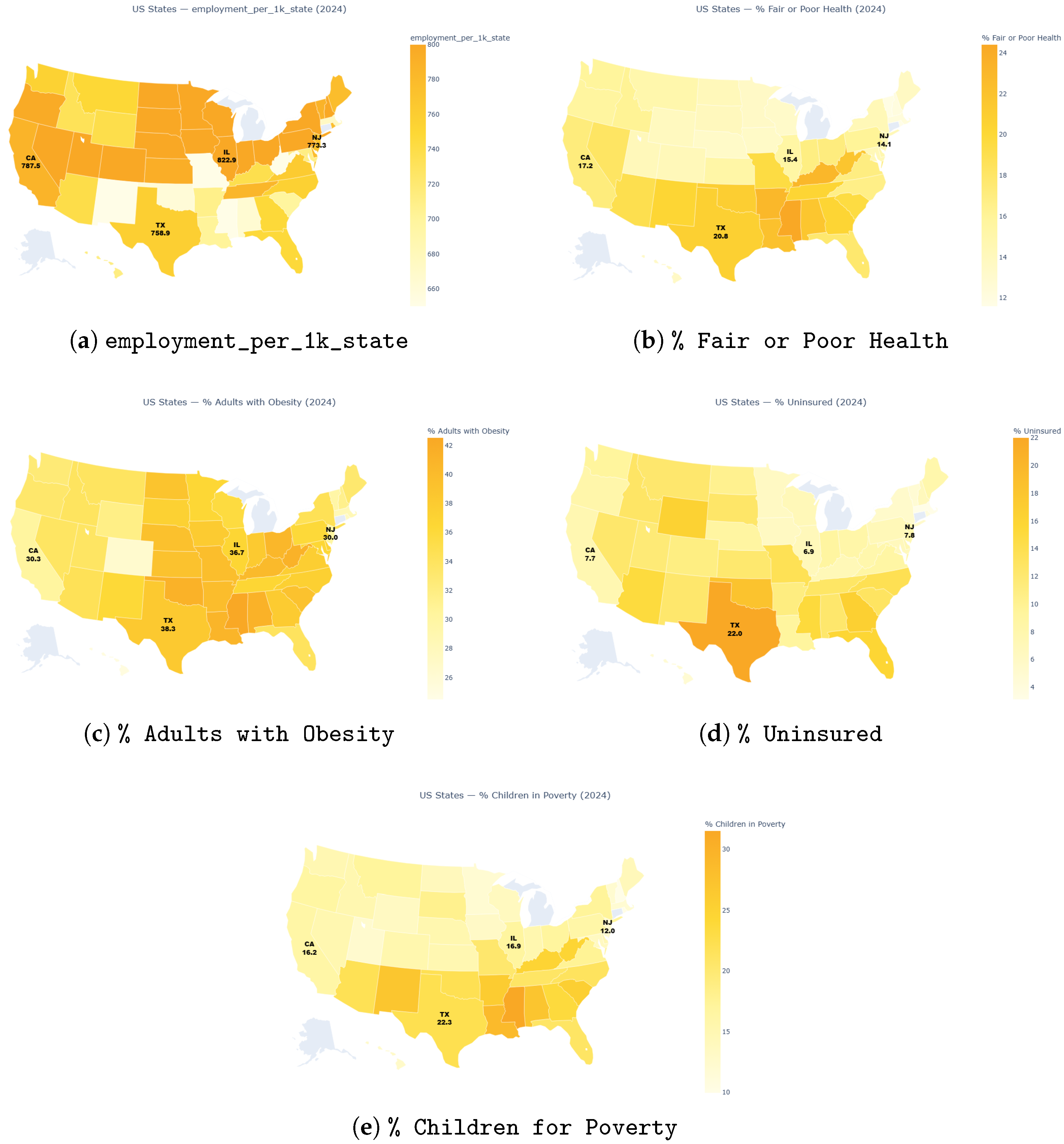

3.2. Spatial Covariance and Regional Clustering

3.2.1. The “Southern Belt” Constraints

3.2.2. Structural Barriers

3.2.3. Health Correlations

3.2.4. Non-Linearity in Industrial Hubs

3.3. Conclusion: Justification for Feature Selection

- The health patterns (specifically obesity) function independently from economic market fluctuations, providing independent predictive value.

- The percentage of uninsured population in each state captures essential policy differences between Texas and California which cannot be measured through poverty statistics alone.

- The “Southern Belt” characteristics show a strong spatial relationship with employment density because this particular set of health, economy, and insurance metrics successfully identifies the core elements determining employment.

4. Methodology

4.1. Feature Screening, Data Cleaning, and Time-Aware Split

4.2. Baseline Models and Initial XGBoost Benchmark

4.3. Regularized XGBoost Specification

4.4. Stacked Ridge Ensemble as Robustness Check

4.5. Final Model Choice and SHAP Framework

5. Results

5.1. Baseline Models and Evidence of Overfitting

5.2. Regularized Tree Models, Leakage-Safe Stacking, and Robustness Checks

5.3. SHAP-Based Interpretation of the XGBoost Model

Illustrated Interaction and Non-Linear Effects

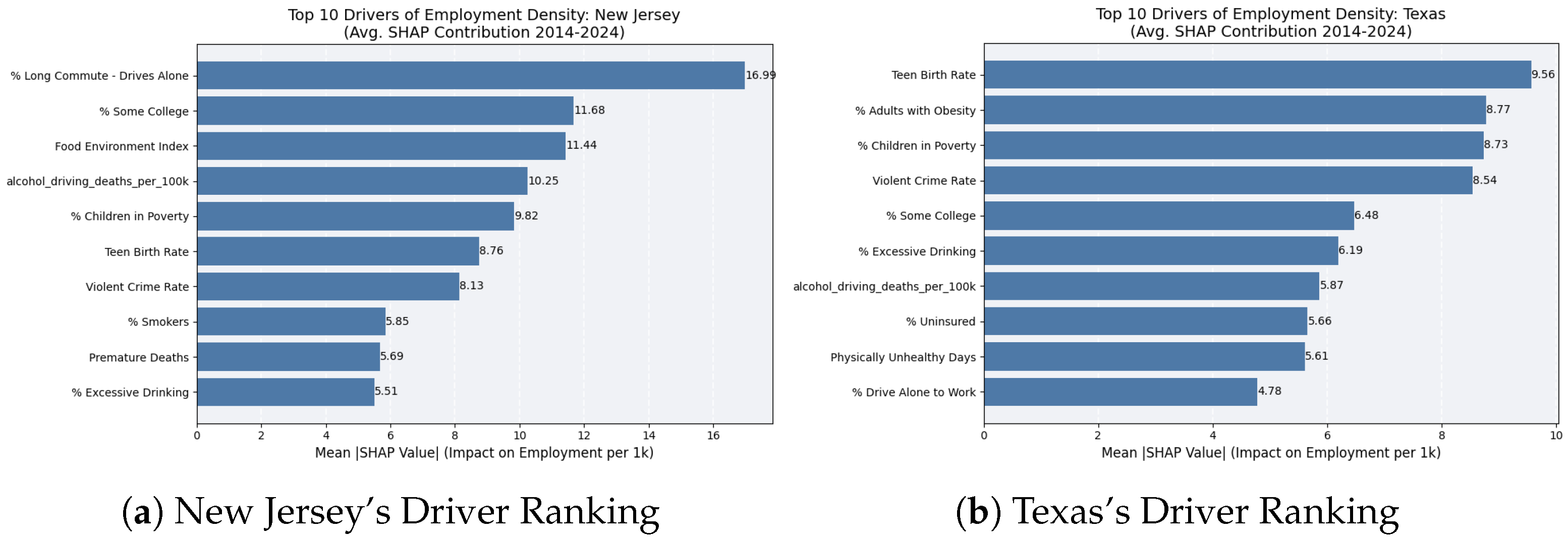

6. Case Study—Comparative Feature Importance

6.1. State Deep Dive: New Jersey

6.2. State Deep Dive: Texas

6.3. Comparative Synthesis: Structural vs. Individual Determinants

7. Discussion

7.1. Applicability to Economic Forecasting and Scenario Planning

7.2. Policy Implications for Integrated Health-Economic Interventions

7.3. Insurance as a Predictor of Labor Stability

7.4. Broader Societal and Research Applicability

8. Limitations and Future Directions

8.1. Limitations

8.1.1. Data Granularity and Comparability

8.1.2. Causal Inference vs. Predictive Power

8.1.3. Temporal Dynamics and Structural Breaks

8.2. Future Directions

8.2.1. Integration of Causal Machine Learning

8.2.2. Granular Modeling with Imputation Strategies

8.2.3. Dynamic “What-If” Policy Simulations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Averett, S.L. Obesity and labor market outcomes. IZA World of Labor 2019, 32. Available online: https://wol.iza.org/articles/obesity-and-labor-market-outcomes/long (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Stock, J.H.; Watson, M.W. Vector Autoregressions. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001, 15, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnichon, R.; Nekarda, C.J. The Ins and Outs of Forecasting Unemployment: Using Labor Force Flows to Forecast the Labor Market. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2012, 2012, 83–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozay, D.; Jahanbakht, M.; Wang, S. Exploring the Intersection of Big Data and AI with CRM through Descriptive, Network, and Contextual Methods. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 57223–57240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhao, X.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Mu, H. A stable technical feature with GRU-CNN-GA fusion. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 187, 114302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, A.; Deaton, A. Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, S.H.; Aron, L.Y. (Eds.) U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW). 2025. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/qcew (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS) 5-Year Data. 2025. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps Technical Documentation: 2025 Annual Data Release; Technical Report; University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute: Madison, WI, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Remington, P.L.; Catlin, B.B.; Gennuso, K.P. The County Health Rankings: Rationale and methods. Popul. Health Metric. 2015, 13, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005, 365, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, J.; Madrian, B.C. Health, health insurance and the labor market. In Handbook of Labor Economics; Ashenfelter, O., Card, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 3, pp. 3309–3416. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.; Qu, C. Modular Landfill Remediation for AI Grid Resilience. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2512.19202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Selective Layer Fine-Tuning for Federated Healthcare NLP: A Cost-Efficient Approach. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Computer, Data Sciences and Applications (ACDSA 2025), Antalya, Turkiye, 7–9 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L. Selective Attention Federated Learning: Improving Privacy and Efficiency for Clinical Text Classification. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Computer, Data Sciences and Applications (ACDSA 2025), Antalya, Turkiye, 7–9 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Z.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yin, Y.; He, S.; Cheng, Y. Early warning of cryptocurrency reversal risks via multi-source data. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 85, 107890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celbiş, M.G. Unemployment in rural Europe: A machine learning perspective. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2023, 16, 1071–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Wang, Y.; Ke, Z.; Shen, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, R.; Ouyang, K. A Generative Adversarial Network-Based Investor Sentiment Indicator: Superior Predictability for the Stock Market. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, L. When Large Language Models Do Not Work: Online Incivility Prediction through Graph Neural Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2512.07684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Yun, T.; Feng, P.; Huang, J.; Tang, R. Taco: Enhancing multimodal in-context learning via task mapping-guided sequence configuration. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Suzhou, China, 4–9 November 2025; pp. 736–763. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, B.; He, H.; Yao, Z.; Han, L.; Chen, Y.V.; Fei, S.; Liu, D.; et al. Cama: Enhancing multimodal in-context learning with context-aware modulated attention. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.17097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Shen, Z.; Han, L.; Xu, H.; Tang, R. CATP: Contextually Adaptive Token Pruning for Efficient and Enhanced Multimodal In-Context Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.07871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 4766–4775. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Wang, Y. SHAP Stability in Credit Risk Management: A Case Study in Credit Card Default Model. Risks 2025, 13, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Final Value | Tuning Range |

|---|---|---|

| n_estimators | 800 | 200–1000 (step 50) |

| learning_rate | 0.05 | {0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.05, 0.08, 0.10, 0.15} |

| max_depth | 5 | 2–6 |

| min_child_weight | 5 | 3–15 |

| gamma | 2.0 | {0.0, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0} |

| subsample | 0.6 | {0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9} |

| colsample_bytree | 0.6 | {0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9} |

| colsample_bylevel | 0.5 | {0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9} |

| reg_alpha | 0.0 | {0.0, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0} |

| reg_lambda | 2.0 | {1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10.0} |

| Train (Years ≤ 2019) | Test (Years > 2019) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | ||

| LASSO | 0.875 | 46.714 | 34.774 | 0.675 | 72.654 | 52.998 |

| XGBoost (baseline) | 1.000 | 0.795 | 0.630 | 0.569 | 83.642 | 47.236 |

| MLP | 0.970 | 22.889 | 16.769 | 0.228 | 111.926 | 89.696 |

| Train (Years ≤ 2019) | Test (Years > 2019) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | ||

| LASSO (regularized) | 0.875 | 46.827 | 34.858 | 0.676 | 72.528 | 52.838 |

| XGBoost (tuned, regularized) | 1.000 | 2.278 | 1.070 | 0.800 | 56.965 | 40.097 |

| Random Forest (regularized) | 0.610 | 82.705 | 36.359 | 0.389 | 99.550 | 57.779 |

| Stacked ensemble (Ridge; OOF meta-train) | 0.908 | 40.369 | 24.926 | 0.827 | 53.001 | 38.676 |

| Model | OOF Years | n | / | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuned XGBoost (walk-forward OOF) | 2016–2019 | 197 | 0.899 | 42.266/24.558 |

| Stacked ensemble (OOF meta-train) | 2016–2019 | 197 | 0.908 | 40.369/24.926 |

| Test Year | RMSE | MAE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 0.939 | 31.838 | 22.538 |

| 2019 | 0.968 | 23.005 | 15.518 |

| 2020 | 0.815 | 53.180 | 42.198 |

| 2021 | 0.938 | 29.681 | 22.105 |

| 2022 | 0.877 | 44.276 | 37.551 |

| 2023 | 0.816 | 54.323 | 30.799 |

| 2024 | 0.790 | 61.186 | 34.164 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, D.; Shen, Q.; Liu, J. The Health-Wealth Gradient in Labor Markets: Integrating Health, Insurance, and Social Metrics to Predict Employment Density. Computation 2026, 14, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation14010022

Liu D, Shen Q, Liu J. The Health-Wealth Gradient in Labor Markets: Integrating Health, Insurance, and Social Metrics to Predict Employment Density. Computation. 2026; 14(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation14010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Dingyuan, Qiannan Shen, and Jiaci Liu. 2026. "The Health-Wealth Gradient in Labor Markets: Integrating Health, Insurance, and Social Metrics to Predict Employment Density" Computation 14, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation14010022

APA StyleLiu, D., Shen, Q., & Liu, J. (2026). The Health-Wealth Gradient in Labor Markets: Integrating Health, Insurance, and Social Metrics to Predict Employment Density. Computation, 14(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation14010022