Permutation-Based Trellis Optimization for a Large-Kernel Polar Code Decoding Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Large-Kernel Polar Code

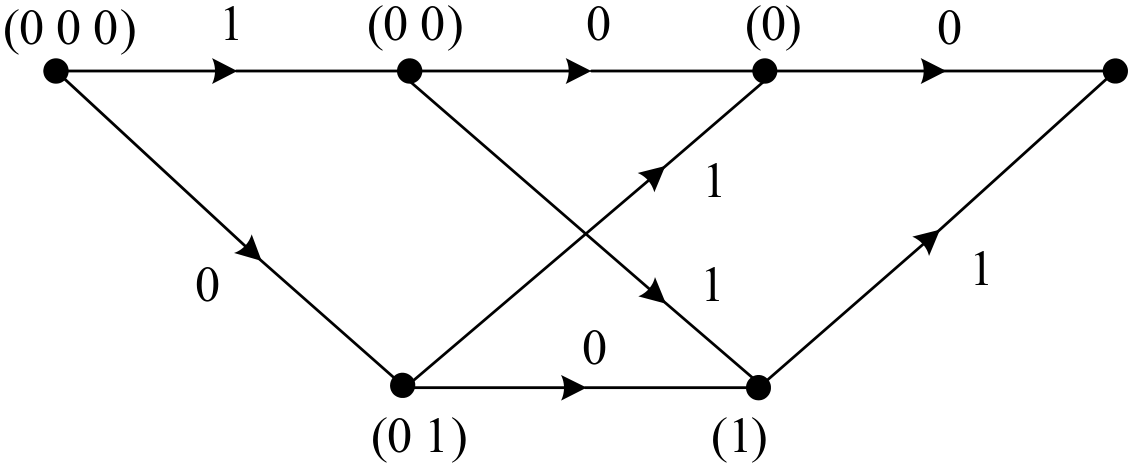

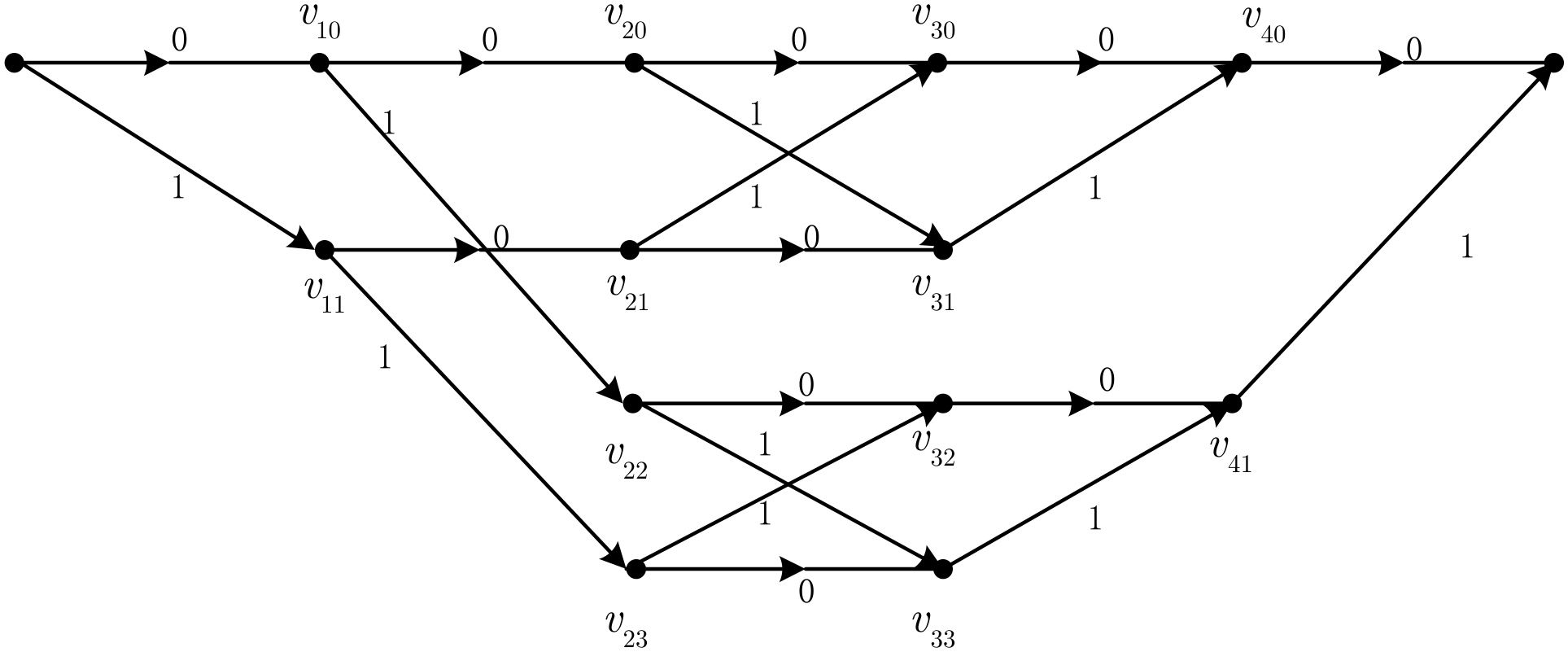

2.2. Time Axis of a Trellis

2.3. Connecting SC Decoding to Trellis Computation

3. Permutation-Based Trellis Optimization

4. ACO-Based Time-Axis Permutation Optimization for Larger Kernels

4.1. Concepts and Basic Steps of the ACO Algorithm

4.1.1. Ants

4.1.2. Time-Axis Permutation Scheme

4.1.3. Pheromone

4.1.4. Iterative Optimal and Global Optimal

4.1.5. Pheromone Update Rules

4.1.6. Convergence Factor

4.1.7. Roulette Wheel Selection

- (1)

- Generate a uniformly distributed random number in [0, 1].

- (2)

- Determine an index such that

- (3)

- Choose as the branch for this ant at that time point.

4.1.8. Generate Time-Axis Permutation Scheme

- (1)

- Start from the starting point , and set .

- (2)

- Calculate the probability of each branch for time point according to Equation (13). Then, choose the branch for time point according to the “roulette wheel selection”.

- (3)

- Increment by 1. Repeat (2) until .

4.2. Algorithm Design

- (1)

- If or the maximum number of iterations has not been reached, the algorithm returns to Step 2 to commence the next iteration.

- (2)

- Otherwise, the algorithm terminates and outputs the final result.

5. Simulation Results and Analysis for Polar Codes with – Kernels

6. Simulation Results and Analysis for Polar Codes with – Kernels

6.1. Parameter Settings

6.1.1. Analysis of the Number of Ants

6.1.2. Analysis of the Pheromone Evaporation Coefficient

6.1.3. Analysis of the Pheromone Intensity

6.2. Simulation Results and Analysis

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B-DMC | Binary input discrete memoryless channel |

| NR | New radio |

| LDPC | low-density parity-check |

| SC | Successive cancellation |

| SCL | Successive cancellation list |

| ACO | Ant colony optimization |

References

- Arikan, E. Channel polarization: A method for constructing capacity-achieving codes for symmetric binary-input memoryless channels. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2009, 55, 3051–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indoonundon, M.; Fowdur, T.P. Overview of the challenges and solutions for 5G channel coding schemes. J. Inf. Telecommun. 2021, 5, 460–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglik, S.; Potapova, V.; Frolov, A. On Performance of Multilevel Coding Schemes Based on Non-Binary LDPC Codes. In Proceedings of the European Wireless 2018, 24th European Wireless Conference, Catania, Italy, 2–4 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Korada, S.B.; Şaşoğlu, E.; Urbanke, R. Polar codes: Characterization of exponent, bounds, and constructions. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2010, 56, 6253–6264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonov, P.V.; Trofimiuk, G.A. Design of Polar Codes with Large Kernels. Probl. Inf. Transm. 2024, 60, 304–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-P.; Lin, S.; Abdel-Ghaffar, K.A.S. Linear and nonlinear binary kernels of polar codes of small dimensions with maximum exponents. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2015, 61, 5253–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, I.; Vardy, A. List decoding of polar codes. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2015, 61, 2213–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timokhin, I.; Ivanov, F. Sequential Polar Decoding with Cost Metric Threshold. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardy, A. Trellis Structure of Codes. In Handbook of Coding Theory; Pless, V.S., Huffman, W.C., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 1989–2118. [Google Scholar]

- Trifonov, P. Recursive Trellis Processing of Large Polarization Kernels. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT), Melbourne, Australia, 12–20 July 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonov, P.; Karakchieva, L. Recursive Processing Algorithm for Low Complexity Decoding of Polar Codes With Large Kernels. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2023, 71, 5039–5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, X. On the Non-Approximate Successive Cancellation Decoding of Binary Polar Codes with Medium Kernels. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 87505–87519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S. A trellis decoding based on Massey trellis for polar codes with a ternary kernel. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Optics and Communication Technology (ICOCT 2023), Changchun, China, 15 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stützle, T.; Hoos, H.H. MAX-MIN Ant System. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2000, 16, 889–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Kernel Size | (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (e) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 9.3 | 3.7 | 8.7 | 10.6 | 10.0 |

| 4 | 22.5 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 17.5 | 15.5 |

| 5 | 49.6 | 7.8 | 19.2 | 26.4 | 21.2 |

| 6 | 105.0 | 11.3 | 25.3 | 35.6 | 27.6 |

| 7 | 217.7 | 21.9 | 33.7 | 52.5 | 37.7 |

| 8 | 446.3 | 42.8 | 44.8 | 71.7 | 46.7 |

| 9 | 908.4 | 52.1 | 56.7 | 91.1 | 58 |

| 10 | 1841.4 | 83.8 | 67.4 | 123.0 | 64.2 |

| 11 | 3721.8 | 246.0 | 118.5 | 159.6 | 91.2 |

| 12 | 7505.5 | 673.8 | 171.0 | 217.8 | 115.8 |

| Number of Ants | Total Number of Optimal Trellis Edges | Number of Iterations to Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| 30 | 220 | 57 |

| 40 | 220 | 61 |

| 50 | 220 | 49 |

| 60 | 220 | 41 |

| 70 | 220 | 33 |

| 80 | 220 | 23 |

| 90 | 220 | 20 |

| 100 | 220 | 20 |

| 110 | 220 | 22 |

| 120 | 220 | 21 |

| Initial Evaporation Coefficient | Total Number of Optimal Trellis Edges | Number of Iterations to Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 220 | 35 |

| 0.2 | 220 | 17 |

| 0.3 | 220 | 13 |

| 0.4 | 220 | 14 |

| 0.5 | 220 | 19 |

| 0.6 | 220 | 20 |

| 0.7 | 220 | 23 |

| 0.8 | 236 | 24 |

| 0.9 | 236 | 22 |

| 1.0 | 252 | 27 |

| Pheromone Intensity | Total Number of Optimal Trellis Edges | Number of Iterations to Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 220 | 23 |

| 20 | 220 | 16 |

| 30 | 220 | 16 |

| 40 | 220 | 13 |

| 50 | 220 | 12 |

| 60 | 220 | 17 |

| 70 | 220 | 23 |

| 80 | 220 | 27 |

| 90 | 220 | 29 |

| 100 | 220 | 27 |

| Kernel Size | (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | (e) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 15,121.8 | 1271.5 | 240.2 | 297.2 | 130.3 |

| 14 | 30,425.6 | 3790.6 | 372.0 | 355.3 | 160.7 |

| 15 | 61,165.1 | 10,736.6 | 481.3 | 446.9 | 205.1 |

| 16 | 122,878.1 | 34,145.0 | 630.1 | 606.8 | 263.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Diao, C.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Huang, Z. Permutation-Based Trellis Optimization for a Large-Kernel Polar Code Decoding Algorithm. Information 2026, 17, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020127

Diao C, Wang Z, Xiao Y, Zhang F, Huang Z. Permutation-Based Trellis Optimization for a Large-Kernel Polar Code Decoding Algorithm. Information. 2026; 17(2):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020127

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiao, Chunjuan, Zhenling Wang, Ying Xiao, Feifei Zhang, and Zhiliang Huang. 2026. "Permutation-Based Trellis Optimization for a Large-Kernel Polar Code Decoding Algorithm" Information 17, no. 2: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020127

APA StyleDiao, C., Wang, Z., Xiao, Y., Zhang, F., & Huang, Z. (2026). Permutation-Based Trellis Optimization for a Large-Kernel Polar Code Decoding Algorithm. Information, 17(2), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020127