1. Introduction

Today, relational databasesplay a central roles in information systems by managing large volumes of data efficiently. Database programming using Structured Query Language (SQL) has become a core skill for data scientists and software developers [

1]. A lot of universities and professional schools offer courses related to SQL in their curricula, teaching data definitions, retrievals, and manipulations [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, despite its importance, database programming is not offered in many universities, and novice students often struggle to write correct SQL queries because of their complexity, making both syntactic and semantic mistakes that hinder learning progress [

7,

8,

9].

The difficulties faced by novice students can be effectively addressed through the lens of Cognitive Load Theory (CLT). Novice learners often struggle with high intrinsic cognitive load stemming from the inherent complexity of SQL logic, which is frequently compounded by the extraneous cognitive load associated with configuring and managing complex database environments. To facilitate effective learning, it is crucial to minimize these extraneous demands and manage intrinsic difficulty through scaffolding, thereby freeing up working memory resources for germane load—the active construction of knowledge schemas. Guided by these principles, this study aims to optimize the learning process by providing a streamlined, web-based environment and structurally sequenced exercises.

To address these cognitive load challenges in SQL learning, we have developed a web-based Programming Learning Assistant System (PLAS) to support self-study of popular programming languages such as Java, Python, and JavaScript. PLAS is designed and implemented to help novice students study programming by themselves through solving various types of exercises. Among them, we implemented the grammar-concept understanding problem (GUP) and the comment insertion problem (CIP) for learning keyword meaning and basic syntax of SQL programming as its initial studies. These exercises may help students in initial recognition and grammar understanding. However, they do not provide realistic practices in composing SQL queries for database tables.

To provide realistic practice, instructors encounter challenges when designing varied SQL programming exercises. This task typically entails constructing diverse database schemas and crafting matching queries, which is time-consuming and often repetitive [

10]. Recent studies show that automatic schema generation by generative AI such as ChatGPT-3.5 can produce reasonable cores but often inconsistent relationships and redundancy, indicating the need for careful validation [

10]. Thus, teachers need tools that can reduce manual works while ensuring schema correctness and pedagogical values.

In this paper, we propose an SQL Query Description Problem (SDP) as a new exercise type inside PLAS. An SDP instance contains a database table schema and a set of questions that require students to write SQL queries for data retrieval or manipulation with their correct answers. Student answers are evaluated automatically using enhanced string matching against a bank of canonical solutions that includes multiple semantically equivalent variants. To reduce preparation efforts and increase variety, we also propose a generative AI-assisted SQL query generator that combines large human-labelled schema collections called Spider dataset [

11] with popular generative AI models such as ChatGPT 5.0 [

12] and Gemini 3.0 Pro [

13] to produce candidate schemas, questions, and reference SQL queries to the dataset.

For evaluation, we generated 11 SDP instances on fundamental SQL topics using the generator with the two generative AI models. The correctness of them was manually validated by teachers before use. We found that ChatGPT-5.0 demonstrated superior technical efficiency with fewer execution errors and a lower mean error rate, making it highly effective for rapid query generation. However, Gemini 3.0 Pro emerged as the more consistent model for pedagogical purposes, achieving perfect scores in Sensibleness, Topicality, and Readiness with absolute inter-rater consensus (). While Gemini 3.0 Pro required slightly more manual syntax debugging than ChatGPT-5.0, its superior instructional alignment and logical stability make it more suitable for the standardized requirements of this study.

Then, we assigned the SDP instances to 32 undergraduate students at the Indonesian Institute of Business and Technology (INSTIKI) during a 120-min class. Our analysis of student performances showed that the average correct answer rate was 95.2% and the average number of submissions was 1.56 per question. The usability test using a questionnaire yielded 78 (Grade B) for the average SUS score. These results indicate that the proposed SDP with the AI-assisted generator using Gemini 3.0 Pro can be a reliable solution for SQL programming studies by novice students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.W.W. and N.F.; methodology, N.W.W. and H.H.S.K.; SDP application, N.W.W. and Z.Z.; AI Assistance Exercise Generator, Z.Z. and I.N.D.K.; visualization, N.W.W. and P.S.; validation, N.W.W. and I.N.A.S.P.; writing—original draft, N.W.W.; writing—review and editing, N.F.; supervision, N.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted following the ethical guidelines of the Indonesian Institute of Business and Technology (INSTIKI). Formal approval from the Institutional Review Board was not required because the research involved normal educational practices and anonymized academic performance data, posing no risks to participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was implied through voluntary participation in the programming exercises. All participants were informed that their anonymized performance data would be used for research purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the colleagues in the Distributing System Laboratory at Okayama University and the Department of Informatics Engineering at the Indonesian Institute of Business and Techonology (INSTIKI) who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rahmalan, H.; Ahmad, S.S.S.; Affendey, L.S. Investigation on Designing a Fun and Interactive Learning Approach for Database Programming Subject According to Students’ Preferences. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1529, 022076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, S.H.; Lin, T.T.; Lin, Y.H. An Exercise Management System for Teaching Programming. J. Softw. 2013, 8, 1718–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, P.; Mariani, J. Learning SQL in Steps. Learning 2015, 12, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Migler, A.; Dekhtyar, A. Mapping the SQL Learning Process in Introductory Database Courses. In Proceedings of the 51st ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE ’20), Portland, OR, USA, 11–14 March 2020; pp. 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Hurst, J.; Mitchell, I.; Gunstone, D. An Exploration of Internal Factors Influencing Student Learning of Programming. In Proceedings of the Eleventh Australasian Conference on Computing Education (ACE ’09), Wellington, New Zealand, 1 January 2009; Volume 95, pp. 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Piteira, M.; Costa, C. Learning Computer Programming: Study of Difficulties in Learning Programming. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Information Systems and Design of Communication (ISDOC ’13), Lisboa, Portugal, 11–12 July 2013; pp. 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahadi, A.; Behbood, V.; Vihavainen, A.; Prior, J.; Lister, R. Students’ Syntactic Mistakes in Writing Seven Different Types of SQL Queries and Its Application to Predicting Students’ Success. In Proceedings of the 47th ACM Technical Symposium on Computing Science Education (SIGCSE ’16), Memphis, TN, USA, 2–5 March 2016; pp. 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipalus, T. The Effects of Database Complexity on SQL Query Formulation. J. Syst. Softw. 2020, 170, 110576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipalus, T.; Perälä, P. What to Expect and What to Focus on in SQL Query Teaching. In Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE ’19), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 27 February 2019–2 March 2019; pp. 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, W.; Fletcher, G.; Miedema, D. A Feasibility Study on Automated SQL Exercise Generation with ChatGPT-3.5. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Data Systems Education: Bridging Education Practice with Education Research (DataEd ’24), Santiago, Chile, 9 June 2024; pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, R.; Yang, K.; Yasunaga, M.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Ma, J.; Li, I.; Yao, Q.; Roman, S.; et al. Spider: A Large-Scale Human-Labeled Dataset for Complex and Cross-Domain Semantic Parsing and Text-to-SQL Task. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2018), Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018; pp. 3911–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Introducing GPT-5. 2025. Available online: https://openai.com/index/introducing-gpt-5/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Google DeepMind. Gemini 3.0 Pro. 2025. Available online: https://deepmind.google/models/gemini/pro/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Mitrovic, A. Learning SQL with a Computerized Tutor. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE ’98), Atlanta, GA, USA, 26 February–1 March 1998; pp. 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhuseyinoglu, K.; Hardt, R.; Barria-Pineda, J.; Brusilovsky, P.; Pollari-Malmi, K.; Sirkiä, T.; Malmi, L. A Study of Worked Examples for SQL Programming. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th ACM Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education—Vol. 1 (ITiCSE 2022), Dublin, Ireland, 8–13 July 2022; pp. 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckin, R.; Holmes, W. Intelligence Unleashed: An Argument for AI in Education; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Chen, P.; Lin, Z. Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 75264–75278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo-Anu, D.; Ansah, L.O. Education in the Era of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI): Understanding the Potential Benefits of ChatGPT in Promoting Teaching and Learning. J. AI 2023, 7, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.C.; Chang, C.I. ChatGPT-5 in Education: New Capabilities and Opportunities for Teaching and Learning. Preprints 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornphol, P.; Chittayasothorn, S. Verification of Relational Database Languages Codes Generated by ChatGPT. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 4th Asia Service Sciences and Software Engineering Conference (ASSE ’23), Aizu-Wakamatsu, Japan, 27–29 October 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, T. Using LLM to Select the Right SQL Query from Candidates. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.02115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.S.; Kumar, N.; Rao, V. AI and Teacher Productivity: A Quantitative Analysis of Time-Saving and Workload Reduction in Education. In Proceedings of the Conference on Advancing Synergies in Science, Engineering, and Management (ASEM 2024), Virginia Beach, VA, USA, 6–9 November 2024; pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hashem, R.; Ali, N.; El Zein, F.; Fidalgo, P.; Abu Khurma, O. AI to the Rescue: Exploring the Potential of ChatGPT as a Teacher Ally for Workload Relief and Burnout Prevention. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2024, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.; Seton, C.; Cooper, G. Applying Cognitive Load Theory to the Redesign of a Conventional Database Systems Course. Comput. Sci. Educ. 2016, 26, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousoof, M.; Sapiyan, M.; Kamaluddin, K. Reducing Cognitive Load in Learning Computer Programming. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Eng. 2007, 1, 3751–3754. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Luo, H. Designing Effective Instructional Feedback Using a Diagnostic and Visualization System: Evidence from a High School Biology Class. Systems 2023, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, K.; Watanuki, S.; Matsuoka, H.; Otake, E.; Yatomi, Y.; Nagaoka, N.; Iino, K. Effects of the Project on Enhancement of Teaching Skills in Gerontic Nursing Practice of Indonesian Nursing Lecturer and Clinical Nurse Preceptor. Glob. Health Med. 2023, 5, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, L., III; Aggarwal, A. Exploring the Effect of Quiz and Homework Submission Times on Students’ Performance in an Introductory Programming Course in a Flipped Classroom Environment. In Proceedings of the 2021 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference, Virtual, 26–29 July 2021; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Rosca, C.M.; Stancu, A. Quality Assessment of GPT-3.5 and Gemini 1.0 Pro for SQL Syntax. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2026, 95, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedema, D.; Taipalus, T.; Aivaloglou, E. Students’ Perceptions on Engaging Database Domains and Structures. In Proceedings of the 54th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE 2023), Toronto, ON, Canada, 15–18 March 2023; Volume 1, pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funabiki, N.; Tana; Zaw, K.K.; Ishihara, N.; Kao, W.C. A Graph-Based Blank Element Selection Algorithm for Fill-in-Blank Problems in Java Programming Learning Assistant System. IAENG Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2017, 44, 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Aung, S.T.; Funabiki, N.; Syaifudin, Y.W.; Kyaw, H.H.S.; Aung, S.L.; Dim, N.K.; Kao, W.C. A Proposal of Grammar-Concept Understanding Problem in Java Programming Learning Assistant System. J. Adv. Inf. Technol. (JAIT) 2021, 12, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Funabiki, N.; Kyaw, H.H.S.; Htet, E.E.; Aung, S.L.; Dim, N.K. Value Trace Problems for Code Reading Study in C Programming. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. (ASTESJ) 2022, 7, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut Bisnis dan Teknologi Indonesia (INSTIKI). Modul Praktikum Basis Data Lanjut. 2022. Available online: https://instiki.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Modul-Praktikum-Basis-Data-Lanjut.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- W3Schools. SQL Tutorial. 2025. Available online: https://www.w3schools.com/sql/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Unal, E.; Çakir, H. Students’ Views about the Problem-Based Collaborative Learning Environment Supported by Dynamic Web Technologies. Malays. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Funabiki, N.; Naing, I.; Kyaw, H.H.S.; Ueda, K. A Proposal of Two Types of Exercise Problems for TCP/IP Programming Learning by C Language. In Proceedings of the IEICE Technical Report, Tokyo, Japan, 31 October 2023; NS2022-236. pp. 396–401. [Google Scholar]

- Sarsa, S.; Denny, P.; Hellas, A.; Leinonen, J. Automatic Generation of Programming Exercises and Code Explanations Using Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research–(ICER ’22), Lugano, Switzerland, 7–11 August 2022; Volume 1, pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwet, K.L. Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability; STATAXIS Publishing Company: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tullis, T.S.; Stetson, J.N. A Comparison of Questionnaires for Assessing Website Usability. In Proceedings of the Usability Professional Association Conference, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 7–11 June 2004; Volume 1, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A Quick and Dirty Usability Scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Jordan, P.W., Thomas, B., Weerdmeester, B.A., McClelland, A.L., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1996; pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

System overview of PLAS.

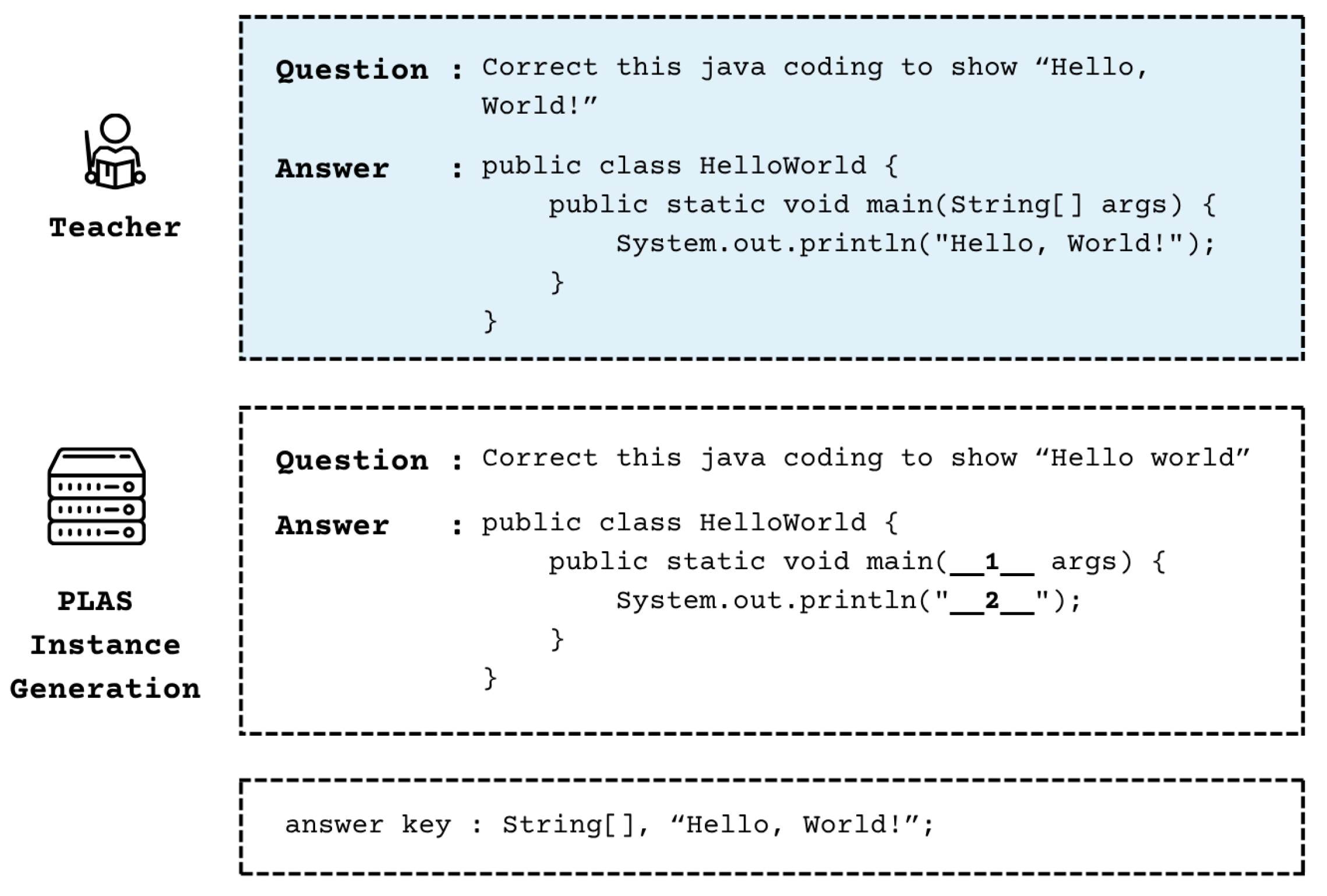

Figure 2.

Example of EFP instance generation.

Figure 3.

Overview of proposal.

Figure 4.

User Interface of Generative AI-assisted SQL query generator interface.

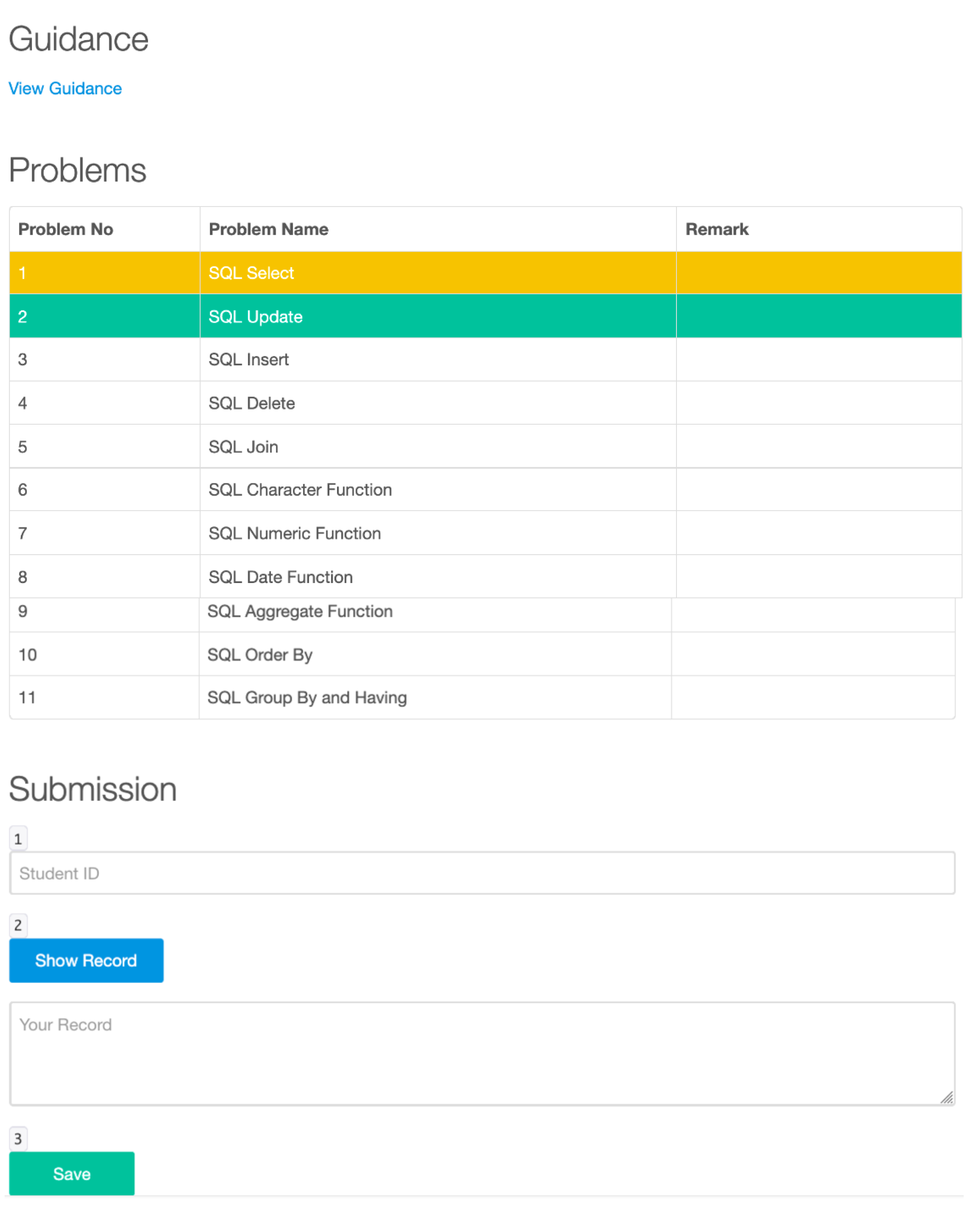

Figure 5.

Screenshot of the instance list page displaying SDP instances and progress status.

Figure 6.

Implementation view of the SDP answer page interface.

Figure 7.

Average correct answer rates and submission times for each SDP instance.

Figure 8.

Average correct answer rates and submission times for each student.

Table 1.

Prompt template for generative AI model to generate SQL question–answer pairs.

| Prompt Template: |

|---|

| “Create 10 SQL questions based on the attached database schema, focusing on [topic], with two levels of difficulty. For each question, provide an explanation and multiple alternative query formulations that are semantically equivalent and yield the same results.” |

Table 2.

Examples of generated question–answer pairs with alternative queries.

| Level | Question | Answer (SQL Query) |

|---|

| Easy | How can you retrieve the names of all departments from the department table? | Option 1:

SELECT dept_name FROM department;

Option 2:

SELECT d.dept_name FROM department AS d; |

| Medium | Write a query to get the names of students (student.name) and the courses they are taking (course.title). Use the student and takes tables. | Option 1:

SELECT s.name, c.title FROM student s JOIN takes t ON s.ID = t.ID JOIN course c ON t.course_id = c.course_id;

Option 2:

SELECT s.name, c.title FROM student s, takes t, course c WHERE s.ID = t.ID AND t.course_id = c.course_id; |

Table 3.

Example of DML-based SDP keyword and question pair.

| Category | Keyword | Question Example |

|---|

| Data Manipulation Language (DML) | INSERT | Write an SQL command to add a new record into the student table with the values (‘S05’, ‘Lisa’, ‘Physics’, 3). |

Table 4.

Examples of keyword and question pairs for data retrieval.

| Category | Keyword | Question Example |

|---|

| Data Retrieval | JOIN | Write a query to display student names and their enrolled course titles by joining the student and takes tables using the student ID. |

| Data Retrieval | ORDER BY | Retrieve all student names and grades from the student table and sort the result in descending order by grade. |

Table 5.

Evaluation metrics for assessing the quality of SQL question–answer pairs generated by generative AI, adapted from Sarsa et al.

| Aspect | Question | Description |

|---|

| A. Subjective Quality Metrics (Assessed by Experts using a 5-Point Likert Scale) |

| Sensibleness | Does the problem description describe a sensible problem? | Assesses the clarity, grammatical accuracy, and factual correctness of the description. (1: Highly Illogical/5: Highly Logical) |

| Novelty | Are we unable to find the SQL exercise via online search (Google) of the problem statement? | Assesses the degree of uniqueness of the SQL query problem/description. (1: Already Existing/5: Highly Novel) |

Topicality:

concept/keyword | Does the answer to the problem statement require the primed concept/keyword? | Assesses the relevance of the description to the requested SQL concepts/keywords. (1: Not Relevant/5: Highly Relevant) |

Topicality:

extras | Does the generated problem statement and solution use the extra primed words (e.g., chain-of-thought, etc.)? | Assesses the quality of integration of additional primed elements into the output. (1: Failure/5: Perfect) |

Readiness:

answer | Is the answer to the generated problem provided? | Assesses the completeness and sufficiency of the description as a learning aid for students. (1: Not Ready/5: Highly Ready) |

| B. Objective Metric (Numerical) |

Readiness:

runnability | How many corrections do we need to make to be able to run the solution query correctly? | Integer |

Table 6.

Interpretation of Kappa Values [

42].

| Kappa Value () | Strength of Agreement |

|---|

| <0.00 | Poor |

| – | Slight |

| – | Fair |

| – | Moderate |

| – | Substantial |

| – | Almost Perfect |

Table 7.

Generated SDP instances with corresponding SQL topics.

| No. | SQL Topic | Number of Questions |

|---|

| 1 | SELECT Statement | 5 |

| 2 | UPDATE Statement | 5 |

| 3 | INSERT Statement | 8 |

| 4 | DELETE Statement | 6 |

| 5 | JOIN Operation | 5 |

| 6 | Character Functions | 9 |

| 7 | Numeric Functions | 8 |

| 8 | Date Functions | 5 |

| 9 | Aggregate Functions | 6 |

| 10 | ORDER BY Clause | 8 |

| 11 | GROUP BY and HAVING Clauses | 4 |

Table 8.

SUS questions.

| No. | Question |

|---|

| 1 | I think that I would like to use this system frequently. |

| 2 | I found the system unnecessarily complex. |

| 3 | I thought the system was easy to use. |

| 4 | I think that I would need the support of a technical person to be able to use this system. |

| 5 | I found the various functions in this system were well integrated. |

| 6 | I thought there was too much inconsistency in this system. |

| 7 | I would imagine that most people would learn to use this system very quickly. |

| 8 | I found the system very cumbersome to use. |

| 9 | I felt very confident using the system. |

| 10 | I needed to learn a lot of things before I could get going with this system. |

Table 9.

Acceptability SUS ranges for user satisfaction levels.

| SUS Score Range | Interpretation |

|---|

| 0–50.9 | Not acceptable |

| 51–70.9 | Marginal |

| 71–100 | Acceptable |

Table 10.

SUS percentile rank interpretation.

| Grade | Score Range |

|---|

| A | Score ≥ 80.3 |

| B | 74 ≤ Score < 80.3 |

| C | 68 ≤ Score < 74 |

| D | 51 ≤ Score < 68 |

| E | Score < 51 |

Table 11.

Global Inter-Rater Reliability Results ().

| Metric | Cohen’s Kappa () | Interpretation |

|---|

| Sensibleness | 0.86 | Almost Perfect Agreement |

| Novelty | 0.91 | Almost Perfect Agreement |

| Topicality: Concept | 1.00 | Almost Perfect Agreement |

| Topicality: Extras | 0.85 | Almost Perfect Agreement |

| Readiness: Answer | 0.87 | Almost Perfect Agreement |

| Runnability (Objective) | 0.72 | Substantial Agreement |

Table 12.

Comparison of Evaluation Scores between ChatGPT and Gemini.

| Metric | ChatGPT | Gemini |

|---|

| | | |

|---|

| Sensibleness | 4.36 | 1.02 | 5.00 | 0.00 |

| Novelty | 1.27 | 0.47 | 1.86 | 0.32 |

| Topicality: Concept | 4.36 | 1.21 | 5.00 | 0.00 |

| Topicality: Extras | 2.95 | 0.15 | 4.68 | 0.46 |

| Readiness: Answer | 4.41 | 0.92 | 5.00 | 0.00 |

Table 13.

Runnability Error Distribution Across 11 Learning Topics ().

| Topic Index | Gemini 3.0 Pro (Errors) | ChatGPT-5.0 (Errors) |

|---|

| Topic 1–5 | 13.0 | 11.5 |

| Topic 6–11 | 22.0 | 18.0 |

| Total Errors | 35.0 | 29.5 |

| Mean Error per Topic | 3.18 ± 2.02 | 2.68 ± 2.14 |

Table 14.

Summary of solution results across SDP instances.

| Number of Students | Average Correct Answer Rate (%) | Standard Deviation | Average Submission Time | Standard Deviation |

|---|

| 32 | 95.20 | 0.08 | 1.56 | 0.82 |

Table 15.

Distribution of responses for questions. All values are expressed as percentages.

| Response | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 |

|---|

| Strongly Disagree | 0.00 | 12.50 | 0.00 | 15.63 | 0.00 | 21.88 | 0.00 | 15.63 | 0.00 | 9.38 |

| Disagree | 0.00 | 71.88 | 0.00 | 68.75 | 0.00 | 56.25 | 0.00 | 68.75 | 0.00 | 68.75 |

| Neutral | 9.38 | 15.63 | 18.75 | 15.63 | 9.38 | 21.88 | 9.38 | 15.63 | 31.25 | 21.88 |

| Agree | 56.25 | 0.00 | 46.88 | 0.00 | 46.88 | 0.00 | 46.88 | 0.00 | 56.25 | 0.00 |

| Strongly Agree | 34.38 | 0.00 | 34.38 | 0.00 | 43.75 | 0.00 | 43.75 | 0.00 | 12.50 | 0.00 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |