A Systematic Review of Ontology–AI Integration for Construction Image Recognition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ontological Perspective

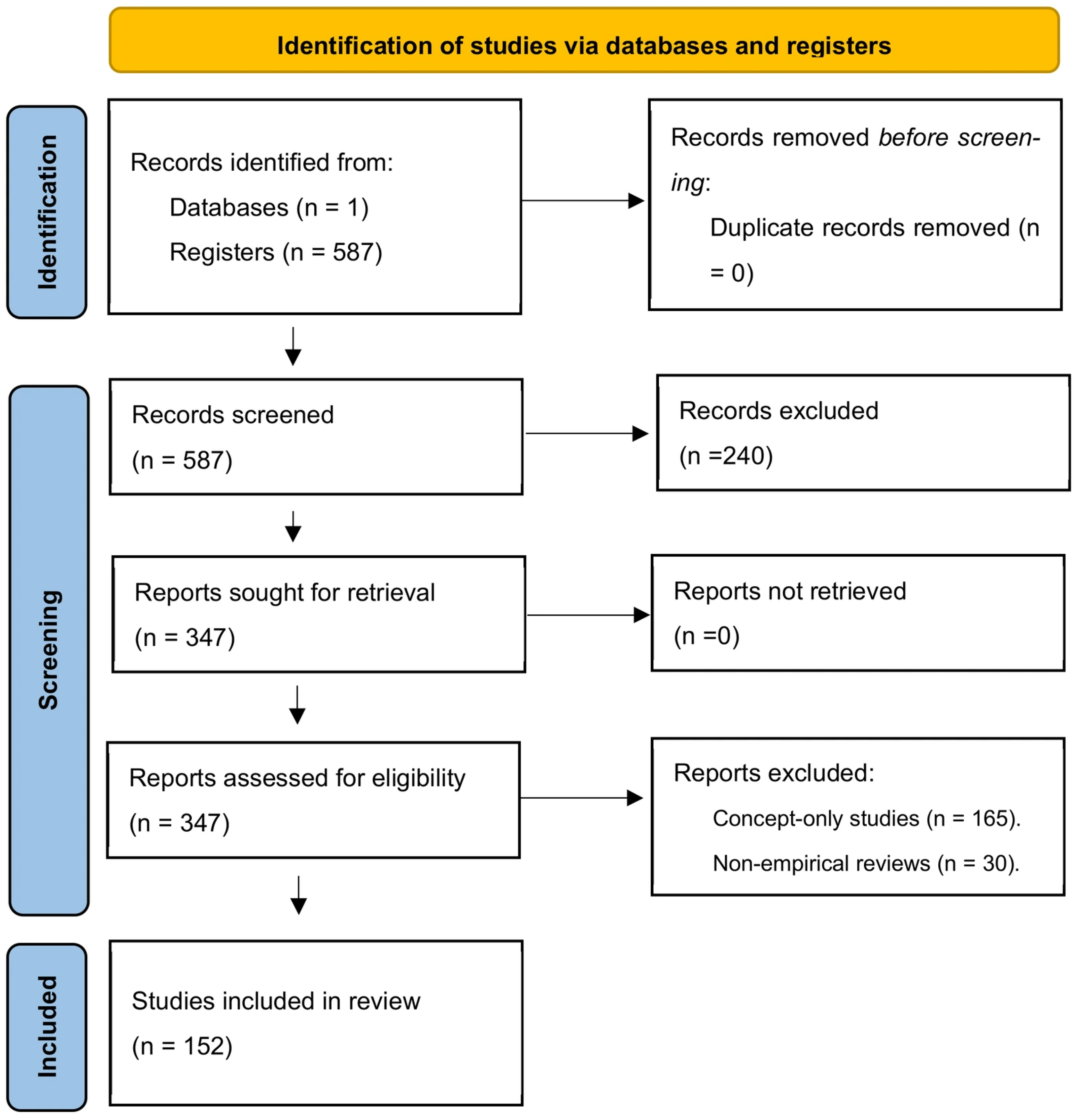

2.2. PRISMA Process

2.3. Data Collection and Extraction

3. Results

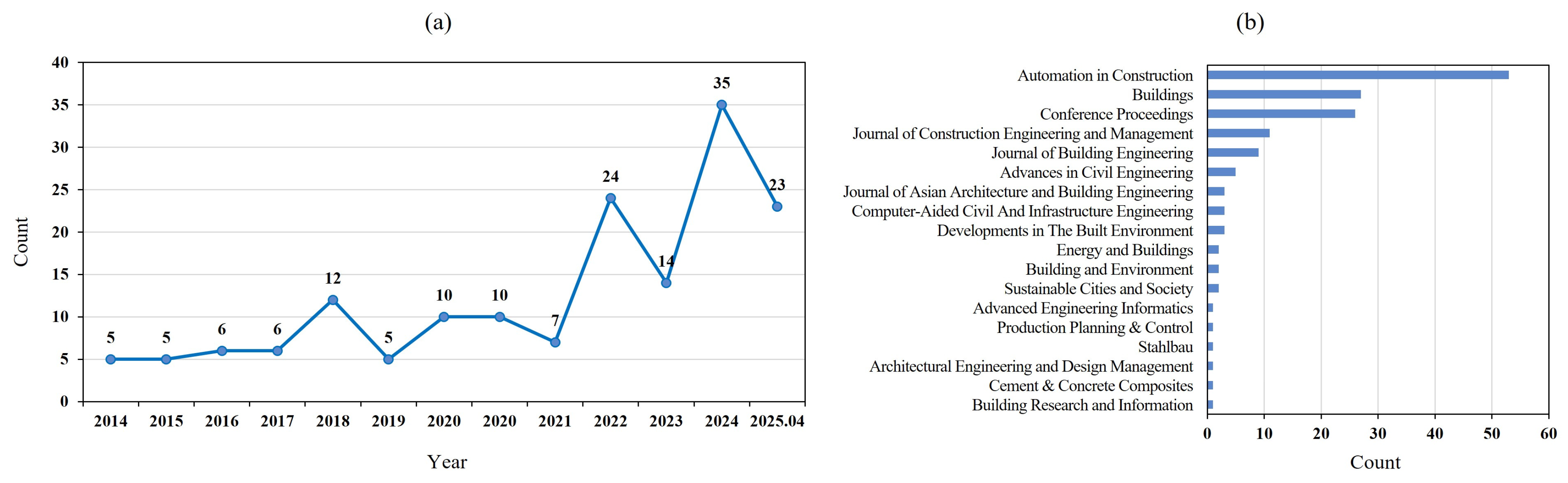

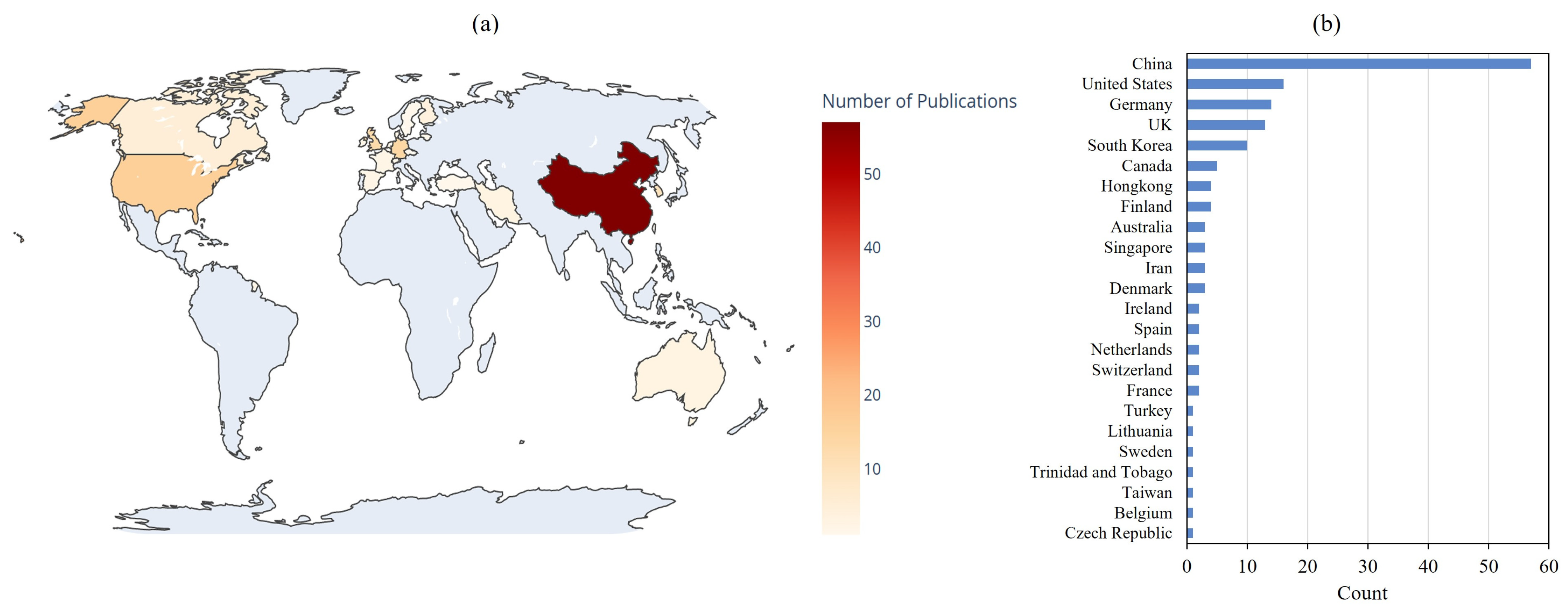

3.1. Bibliometric Overview

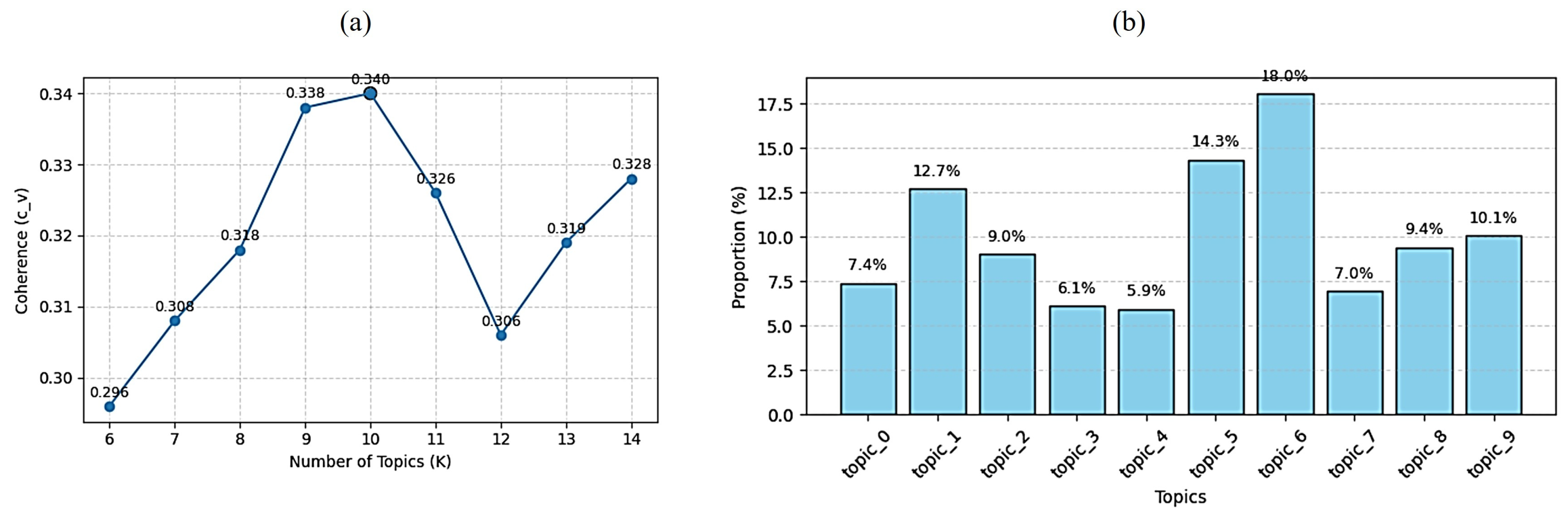

3.2. Topic Modeling-Based Trends in Ontology-Integrated AI Applications

3.3. Integration Types of AI and Ontology

3.4. Ontology-Based Image Recognition in Construction AI

3.4.1. Functional Roles of Ontology in Image Recognition

3.4.2. Ontology Construction Approaches

3.4.3. Image Recognition Models Applied

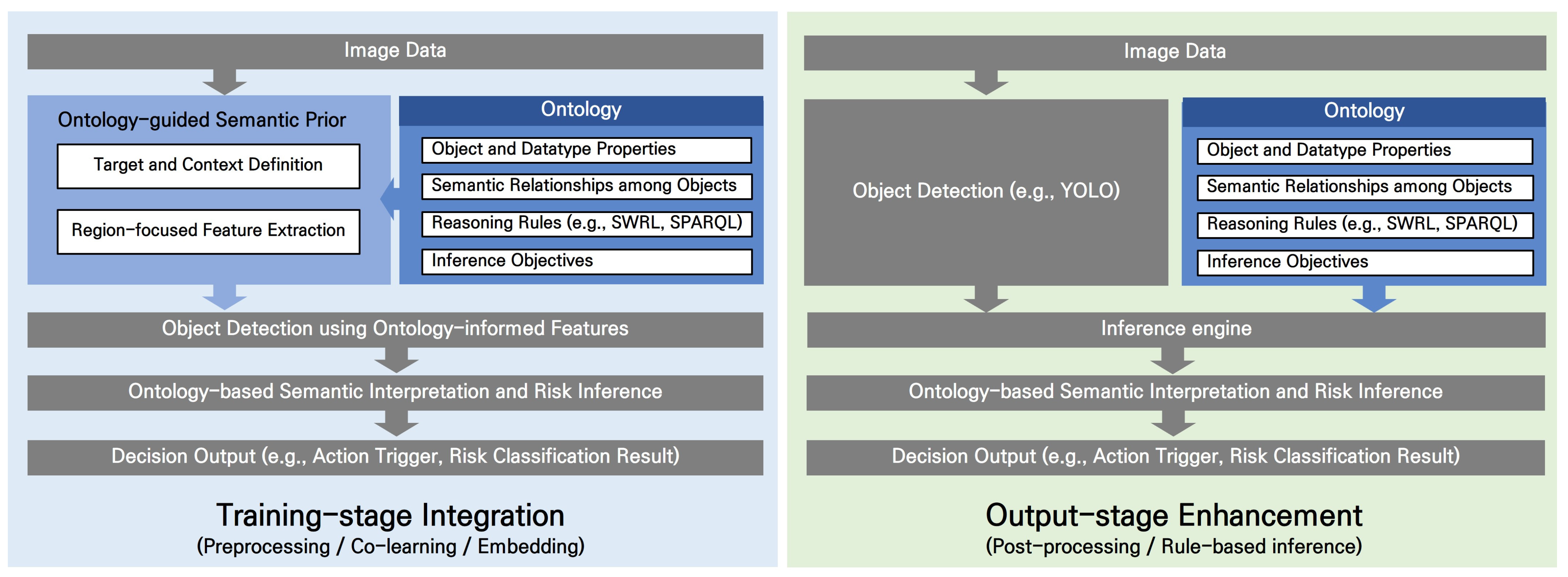

3.4.4. Ontology Implementation Strategies in AI Pipelines

- •

- Preprocessing-based integration uses ontology concepts and relationships for data preprocessing, candidate region filtering, or label refinement. For example, Arslan et al. [28] mapped BLE-based semantic trajectories to ontology concepts, enriching training data with semantic labels and features.

- •

- Transfer and embedding-based integration incorporates ontological hierarchies or embeddings into model initialization or transfer learning stages. Pfitzner et al. [22] combined knowledge graph embeddings with a YOLO detector for semantically informed feature learning, while Pan et al. [31] applied zero-shot label embeddings to reduce the gap between label definitions and recognition outcomes.

- •

- Co-learning integration jointly trains deep learning models and ontology-based knowledge graph models, enabling parallel learning of data-driven features and semantic relationships. Examples include joint training of CNN and GCN architectures or using ontology reasoning outputs as feedback within the training loop. However, no such cases were identified in the construction domain, suggesting that co-learning strategies remain largely experimental due to the high demands of pipeline design and data preparation.

- •

- Class mapping integration connects detected object labels with ontology concepts, enriching them with attributes and relationships for subsequent reasoning or knowledge accumulation. Zheng et al. [24] mapped Mask R-CNN results to a process ontology to classify work status, while Zeng et al. [29] and Pedro et al. [30] linked image data to ontologies to improve training scenarios and visualization quality.

- •

- Rule-based reasoning integration applies ontology-defined rules (e.g., SWRL, SPARQL) to recognition outputs for contextual assessment. Lee and Yu [21] combined YOLO outputs with a safety ontology to infer hazardous conditions in real time, while Fang et al. [26] employed rule-based reasoning with a hazard ontology to automatically detect regulatory violations. Although straightforward to implement and highly compatible with existing models, this approach primarily functions as an interpretive layer rather than directly improving detection performance.

3.4.5. Performance Outcomes

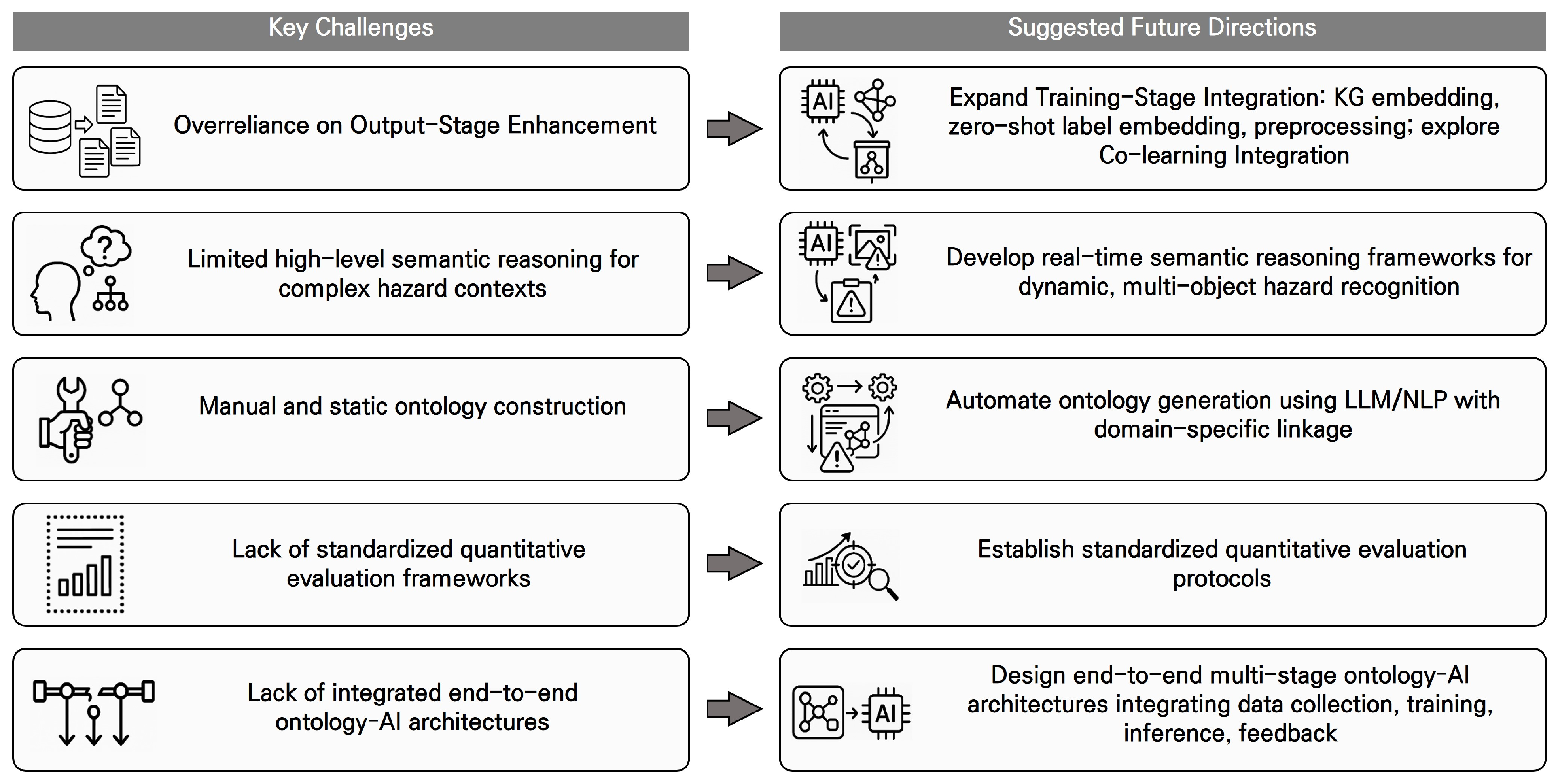

4. Challenges and Future Research on Ontology-AI Integration

4.1. Research Gaps and Limitations

4.2. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bernold, L.E.; Lee, T.S. Experimental research in construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 136, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S.; Leite, F. Assessing safety risk among different construction occupations using occupation-specific data. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 143, 04017007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Safety and Health in Construction; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Employment and Labor. Industrial Accident Status; Ministry of Employment and Labor: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Kim, K.; Jeong, S. Application of YOLO v5 and v8 for Recognition of Safety Risk Factors at Construction Sites. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Liu, M.; Zhao, J. Real-Time Early Safety Warning for Personnel Intrusion Behavior on Construction Sites Using a CNN Model. Buildings 2023, 13, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Liu, G.; Xue, Y.; Li, R.; Meng, L. A survey on dataset quality in machine learning. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2023, 162, 107268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Li, H.; Luo, H.; Zhou, J.; Fang, W.; Xing, X. Ontology-Based Semantic Modeling of Knowledge in Construction for Proactive Hazard Identification. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, e04020013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Lamas, A.; Sanchez, J.; Franchi, G.; Donadello, I.; Tabik, S.; Filliat, D.; Cruz, P.; Montes, R.; Herrera, F. EXplainable Neural-Symbolic Learning (X-NeSyL) methodology to fuse deep learning representations with expert knowledge graphs: The MonuMAI cultural heritage use case. Inf. Fusion 2022, 79, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, B.; Giancarlo, G. On the Multiple Roles of Ontologies in Explainable, A.I. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghaly, K.; Soman, R.; Whyte, J. cSite ontology for production control of construction sites. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluborode, K.O.; Wajiga, G.M.; Malgwi, Y.M. Ontology-Integrated Machine Learning in Computer Vision: A Survey. Multidiscip. Int. J. Res. Dev. (MIJRD) 2024, 03, 116–130. Available online: https://www.mijrd.com/papers/v3/i6/MIJRDV3I60010.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Ghidalia, S.; Alshahrani, M.; Janowicz, K.; Michel, F. Combining machine learning and ontology: A systematic literature review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.07744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. Ontology. In The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Computing and Information; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, R.; Benjamins, V.R.; Fensel, D. Knowledge engineering: Principles and methods. Data Knowl. Eng. 1998, 25, 161–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T.R. A translation approach to portable ontology specifications. Knowl. Acquis. 1993, 5, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, N. Formal Ontology and Information Systems. In Formal Ontology in Information Systems; Guarino, N., Ed.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Zhong, B.; Li, H.; Love, P.; Pan, X.; Zhao, N. Combining computer vision with semantic reasoning for on-site safety management in construction. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 103036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, H.; Han, Z.; Jiang, N.; Wang, W.; Huang, J. Computer Vision-Based Hazard Identification of Construction Site Using Visual Relationship Detection and Ontology. Buildings 2022, 12, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, R.; Posada, H.; Ramonell, C.; Jungmann, M.; Hartmann, T.; Khan, R.; Tomar, R. Digital twinning of building construction processes. Case study: A reinforced concrete cast-in structure. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 74, 108522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Yu, J.H. Ontological inference process using AI-based object recognition for hazard awareness in construction sites. Autom. Constr. 2023, 153, 104961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzner, F.; Staub-French, S.; Li, H.; Hartmann, T. Monitoring concrete pouring progress using knowledge graph-enhanced computer vision. Autom. Constr. 2025, 174, 106117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pileggi, S.F. Ontology in Hybrid Intelligence: A Concise Literature Review. Future Internet 2024, 16, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Masood, M.K.; Seppänen, O.; Törmä, S.; Aikala, A. Ontology-Based Semantic Construction Image Interpretation. Buildings 2023, 13, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, K.; Chen, Y. Dynamic hazard analysis on construction sites using knowledge graphs integrated with real-time information. Autom. Constr. 2025, 158, 106174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Ma, L.; Love, P.E.D.; Luo, H.; Ding, L.; Zhou, A. Knowledge graph for identifying hazards on construction sites: Integrating computer vision with ontology. Autom. Constr. 2020, 119, 103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A.H.; Taraben, J.; Helmrich, M.; Mansperger, T.; Morgenthal, G.; Scherer, R.J. A semantic modeling approach for the automated detection and interpretation of structural damage. Autom. Constr. 2021, 128, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Cruz, C.; Ginhac, D. Semantic trajectory insights for worker safety in dynamic environments. Autom. Constr. 2019, 106, 102854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Hartmann, T.; Ma, L. ConSE: An ontology for visual representation and semantic enrichment of digital images in construction sites. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 60, 102446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, A.; Bao, Q.L.; Hussain, R.; Soltani, M.; Pham, H.C.; Park, C. Learning from construction accidents in virtual reality with an ontology-enabled framework. Autom. Constr. 2024, 166, 105597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Su, C.; Deng, Y.; Cheng, J. Video2Entities: A computer vision-based entity extraction framework for updating the architecture, engineering and construction industry knowledge graphs. Autom. Constr. 2024, 150, 04024121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Shi, J.; Jiang, L. A semantic augmented approach to FEMA P-58 based dynamic regional seismic loss estimation application. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, H.; Park, J.-E.; Seo, M.B.; Yi, J.-S. Graph-based intelligent accident hazard ontology using natural language processing for tracking, prediction, and learning. Autom. Constr. 2024, 168, 105800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.H.; Lefrançois, M.; Pauwels, P.; Hviid, C.A.; Karlshøj, J. Managing interrelated project information in AEC Knowledge Graphs. Autom. Constr. 2019, 108, 102956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgoshaei, P.; Heidarinejad, M.; Austin, M.A. Combined Ontology Driven and Machine Learning Approach to Monitoring of Building Energy Consumption. In Proceedings of the 2018 Building Performance Analysis Conference & SimBuild, Chicago, IL, USA, 26–28 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nabavi, A.; Ramaji, I.; Sadeghi, N. An Artificial Intelligence-Based Framework for Automated Information Inquiry from Building Information Models Using Natural Language Processing and Ontology. ASCE Int. Conf. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2023, 046, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Hou, K. Building a Knowledge Base of Bridge Maintenance Using Knowledge Graph. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 6047489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhong, H.; Wang, Z.; Du, P.; Zhou, K.; Zhou, H.; Lai, X.; Lau, Y.L.; Song, Y.; Tang, L. BEKG: A built environment knowledge graph. Build. Res. Inf. 2022, 52, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukari, O.; Seck, B.; Greenwood, D. The Creation of Construction Schedules in 4D BIM: A Comparison of Conventional and Automated Approaches. Buildings 2022, 12, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Wong, S.; Su, X.; Tang, Y.; Nawaz, A.; Kassem, M. Automating construction contract review using knowledge graph-enhanced large language models. Autom. Constr. 2023, 175, 106179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, C.; Xiong, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Xia, T.; Ji, M. Systematic exploration of the knowledge graph on rock porosity structure. Buildings 2025, 15, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhao, Y. A Knowledge Graph-Based Approach to Recommending Low-Carbon Construction Schemes of Bridges. Buildings 2023, 13, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, A.S.; Nik-Bakht, M. Integrating industry foundation classes and knowledge graphs for automated deconstruction planning. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 106, 112564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, A.; De Luca, L.; Paquet, E.; Rubinetti, S.; Bromberg, I. From surveys to simulations: Integrating Notre-Dame de Paris’ buttressing system diagnosis with knowledge graphs. Autom. Constr. 2024, 170, 105927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Sun, C.T.; Hu, Y.Q.; Kumar, A. BIM and Knowledge Graph-Based Building Material Recycle and Reuse Assessment Framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering 2023, ASCE Library, Corvallis, OR, USA, 25–28 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzner, F.; Braun, A.; Borrmann, A. From data to knowledge: Construction process analysis through continuous image capturing, object detection, and knowledge graph creation. Autom. Constr. 2024, 164, 105451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, G.; Wang, K.; Chen, S.; Duan, C. Knowledge graph for safety management standards of water conservancy construction engineering. Autom. Constr. 2024, 168, 105873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, R.; Xu, S.S.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, H. Intelligent Checking Method for Construction Schemes via Fusion of Knowledge Graph and Large Language Models. Buildings 2024, 14, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; El-Gohary, N. Deep Learning-Based Relation Extraction from Construction Safety Regulations for Automated Field Compliance Checking. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering 2022, ASCE Library, Cape Town, South Africa, 26–28 October 2022; pp. 286–295. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, K.; Liu, Y.; Ding, L. Early-warning of unsafe hoisting operations: An integration of digital twin and knowledge graph. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 19, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Petzold, F. Ontology-Driven Mixture-of-Domain Documentation: A Backbone Approach Enabling Question Answering for Additive Construction. Buildings 2025, 15, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Kang, S.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Jung, Y.S. Standard terms as analytical variables for collective data sharing in construction management. Autom. Constr. 2023, 146, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Torma, S.; Seppanen, O. A Shared Ontology Suite for Digital Construction Workflow. Autom. Constr. 2021, 132, 13930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isah, M.A.; Kim, B.S. Question-Answering System Powered by Knowledge Graph and Generative Pretained Transformer to Support Risk Identification in Tunnel Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 151, 15230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknam, M.; Karshenas, S. A shared ontology approach to semantic representation of BIM data. Autom. Constr. 2017, 80, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenger, J.; Pluta, K.; Mathew, A.; Yeung, T.; Sacks, R.; Borrmann, A. Reference architecture and ontology framework for digital twin construction. Autom. Constr. 2024, 174, 106111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahreinia, F.; Hammad, A.; Ghabraie, K. Ontology for BIM-Based Robotic Navigation and Inspection Tasks. Buildings 2024, 14, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Li, X.; Jiang, R.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z. Graph-based deep learning model for knowledge base completion in constraint management of construction projects. Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2023, 38, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.H.W.; Goh, Y.M. Ontology for design of active fall protection systems. Autom. Constr. 2017, 82, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanda, F.H.; Akintola, A.; Tuhaise, V.V.; Tah, J.H.M. BIM ontology for information management (BIM-OIM). J. Build. Eng. 2025, 107, 112762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matějka, P.; Tomek, A. Ontology of BIM in a Construction Project Life Cycle. Procedia Eng. 2017, 196, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Li, Q.; Zhang, B.; Zhai, X.; Yin, L. An ontology-driven method for urban building energy modeling. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 106, 105394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, P.; Cheng, G.; Chen, Y. Intelligent floor plan design of modular high-rise residential building based on graph-constrained generative adversarial networks. Autom. Constr. 2024, 159, 105264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, M.; Wang, Y.; Ye, G.; Chen, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, X. Ontology-Guided Generation of Mechanized Construction Plan for Power Grid Construction Project. Buildings 2024, 14, 3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, Z. Establishing formalized representation of standards for construction cost estimation by using ontology learning. Procedia Eng. 2015, 123, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; El-Gohary, N.M. Bridge Deterioration Knowledge Ontology for Supporting Bridge Document Analytics. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönfelder, L.; Honic, M.; De Wolf, C. A steel element reuse ontology for building audits in circular construction. Dev. Built Environ. 2025, 21, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Costin, A. BIM and Ontology-Based DfMA Framework for Prefabricated Component. Buildings 2023, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Jin, X.; Shang, Y. Ontology-based automated knowledge identification of safety risks in Metro shield construction. J. Asian Build. Eng. 2025, 9, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkonen, V.; Kücükavci, A.; Seidenschnur, M.; Rasmussen, M.H.; Smith, K.M.; Hviid, C.A. An ontology to support flow system descriptions from design to operation of buildings. Autom. Constr. 2022, 134, 104067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Kim, K.-R.; Yu, J.-H. BIM and ontology-based approach for building cost estimation. Autom. Constr. 2014, 41, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Meng, W.; Bao, Y. Knowledge-guided data-driven design of ultra-high-performance geopolymer (UHPG). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 53, 105723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, S.; Cui, D.D.; Xu, H.; Luo, H. Information Integration of Regulation Texts and Tables for Automated Construction Safety Knowledge Mapping. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Vakaj, E.; Soman, R.K.; Hall, D.M. Ontology-based manufacturability analysis automation for industrialized construction. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, B.; Hu, H. Research on ontology-based construction risk knowledge base development in deep foundation pit excavation. J. Asian Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 1640–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfitzner, F.; Braun, A.; Borrmann, A. Object Detection-Based Knowledge Graph Creation: Enabling Insight into Construction Processes. In Proceedings of the Computing in Civil Engineering, Corvallis, OR, USA, 25–28 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaekel, J.-I.; Heinlein, E.; von Luck, K. Ontology for a Knowledge-Based Deconstruction of Buildings Based on BIM Models and Linked Data Principles. Buildings 2025, 15, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.; Cui, C.; Li, H.; Liu, H. Ontology-Based Approach Supporting Multi-Objective Holistic Decision Making for Energy Pile System. Buildings 2022, 12, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauen, N.; Schlütter, D.; Siwiecki, J.; Frisch, J.; van Treeck, C. Integrated representation of technical systems with BIM and linked data: TUBES system ontology. Autom. Constr. 2024, 165, 105502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukari, O.; Wakefield, J.; Martinez, P.; Kassem, M. An ontology-based tool for safety management in building renovation projects. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; El-Gohary, N. Ontology-based automated information extraction from building energy conservation codes. Autom. Constr. 2017, 74, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, M.; Ma, G. A Semi-Automatic Ontology Development Framework for Knowledge Transformation of Construction Safety Requirements. Buildings 2025, 15, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Xu, M.; Lin, Y.; Cui, C.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y. Safety Risk Management of Prefabricated Building Construction Based on Ontology Technology in the BIM Environment. Buildings 2022, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, C.; Xue, F.; Yang, Z.; Lou, J.; Lu, W. Ontology-based mapping approach for automatic work packaging in modular construction. Autom. Constr. 2022, 134, 104083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenegger, J.; Frandsen, K.M.; Petrova, E. An ontology-driven framework for digital transformation and performance assessment of building materials. Build. Environ. 2025, 271, 112565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, P.; Terkaj, W. EXPRESS to OWL for construction industry: Towards a recommendable and usable ifcOWL ontology. Autom. Constr. 2016, 63, 100–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, C.B.; Badyina, A.; Golubchikov, O. OntoAgency: An agency-based ontology for tracing control, ownership and decision-making in smart buildings. Build. Environ. 2024, 256, 111489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Cai, H.; Chen, K. An Ontology Approach to Utility Knowledge Representation. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2018, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–4 April 2018; pp. 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhi, Y.; Xu, J.; Han, L. Digital Protection and Utilization of Architectural Heritage Using Knowledge Visualization. Buildings 2022, 12, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Chen, Y.; Wei, Y.; Li, C.; Zhu, B. Ontology-Based Knowledge Model to Support Construction Noise Control in China. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 144, 04017103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Boukamp, F.; Teizer, J. Ontology-based semantic modeling of construction safety knowledge: Towards automated safety planning for job hazard analysis (JHA). Autom. Constr. 2015, 52, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, Z. Ontology- and freeware-based platform for rapid development of BIM applications with reasoning support. Autom. Constr. 2018, 90, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhu, H. A Semantic-Based Methodology to Deliver Model Views of Forward Design for Prefabricated Buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Sprenger, W.; Maurer, C.; Kuhn, T.E.; Rüppel, U. Building product ontology: Core ontology for Linked Building Product Data. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 103927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Huo, H.; Pang, S. Identification of Environmental Pollutants in Construction Site Monitoring Using Association Rule Mining and Ontology-Based Reasoning. Buildings 2022, 12, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.Y.; Chi, H.L.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Park, C.S. A linked data system framework for sharing construction defect information using ontologies and BIM environments. Autom. Constr. 2016, 68, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Hei, X. Semiautomatic Generation of Code Ontology Using ifcOWL in Compliance Checking. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 8861625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Issa, R.R.A. Ontology-Based Integration of BIM and GIS for Indoor Routing. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2020: Computer Applications, Tempe, AZ, USA, 8–10 March 2020; pp. 1010–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Costin, A.; Razkenari, M. An Ontology for Manufacturability and Constructability of Prefabricated Component. In Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering 2021, Orlando, FL, USA, 12–14 September 2021; pp. 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, P.; Krijnen, T.; Terkaj, W.; Beetz, J. Enhancing the ifcOWL ontology with an alternative representation for geometric data. Autom. Constr. 2017, 80, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Fischer, M. Ontology for Representing Building Users’ Activities in Space-Use Analysis. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 140, 04019043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawani, S.; Messner, J.; Leicht, R. Developing an Ontology for Implementation of Lean Construction Methods in Construction Projects. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2020: Project Management and Controls, Materials, and Contracts, Tempe, AZ, USA, 8–10 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moyano, J.; Pili, A.; Nieto-Julián, J.E.; Della Torre, S.; Bruno, S. Semantic interoperability for cultural heritage conservation: Workflow from ontologies to a tool for managing and sharing data. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 107965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Cai, H. An Ontology for On-Site Construction Robot Control Using Natural Language Instructions. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2024, Des Moines, IA, USA, 20–23 March 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, S.; Li, Z. Representation and Reasoning for Common Quality Faults of Construction Based on Ontology. In Proceedings of the ICCREM 2015, Luleå, Sweden, 11–14 August 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, H.; Yan, X.; Liu, Z. Ontology-based inference decision support system for emergency response in tunnel vehicle accidents. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, C.; Yan, L. Integration of BIM and ontologies for pumped storage hydropower design change management in EPC projects. Autom. Constr. 2025, 175, 106189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, W.; Yuan, J. Study on the Evaluation Method of Green Construction Based on Ontology and BIM. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 1, 5650463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Das, M.; Chen, K.; Cheng, J.C.P. Ontology-Based Data Integration and Sharing for Facility Maintenance Management. In Construction Research Congress 2020: Computer Applications; Tang, P., Grau, D., El Asmar, M., Eds.; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; pp. 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wei, Z. Formalized Representation of Specifications for Construction Cost Estimation by Using Ontology. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2016, 31, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Jeong, D. A Framework for the Inter-Connection of Life-Cycle Highway Data Islands. In Construction Research Congress 2016: Old and New Construction Technologies Converge in Historic San Juan; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2016; pp. 1393–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zadeh, P.; Staub-French, S. Ontology-Based Design Features for Representing Constructability in Architectural Design: Toward BIM in Off-Site Construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Ontology-Based Representation Model to Support Cause and Effect Analysis. In Proceedings of the ICCREM 2015, Luleå, Sweden, 11–14 August 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Lin, X.; Jiang, H.; An, Y. Automated Building Information Modeling Compliance Check through a Large Language Model Combined with Deep Learning and Ontology. Buildings 2024, 14, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Xu, J.; Shu, Y.; Liu, H.; Xiao, J. Ontology-Based Integrated Cost Management System for Real Estate De-velopment. In Proceedings of the ICCREM 2022, Virtual Conference, 17–18 December 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Shi, J.; Pan, Z.; Chen, P. Information Integrated Management of Prefabricated Project Based on BIM and Knowledge Flow Based Ontology. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2020, Tempe, AZ, USA, 8–10 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Ahn, S. PageRank Algorithm-Based Recommendation System for Construction Safety Guidelines. Buildings 2024, 14, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Tang, L.; Webster, C.; Xu, S.; Li, X.; Ying, H. An ontology-aided, natural language-based approach for multi-constraint BIM model querying. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, H.; Sebt, M.H.; Shakeri, E. Toward improving the quality compliance checking of urban private constructions in Iran: An ontological approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.W.; Schultz, C.; Teizer, J. Hazard ontology and 4D benchmark model for facilitation of automated construction safety requirement analysis. Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2023, 38, 2128–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Liu, R. Improving for Construction Safety Design: Ontology Model of a Knowledge System for the Prevention of Falls. In Construction Research Congress 2020: Safety, Workforce, and Education; El Asmar, M., Grau, D., Tang, P., Eds.; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; pp. 463–471. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, B.; Shi, J.; Jiang, L.; Pan, Z. A Semantic Approach to Dynamic Path Planning for Fire Evacuation through BIM and IoT Data Integration. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2024, 8839865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xiao, G.; Sun, L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Z. Associative reasoning for engineering drawings using an interactive attention mechanism. Autom. Constr. 2025, 170, 105942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Pishdad-Bozorgi, P.; Shelden, D.; Tang, S. Machine Learning-Based Building Life-Cycle Cost Prediction: A Framework and Ontology. In Construction Research Congress 2020: Computer Applications; Tang, P., Grau, D., El Asmar, M., Eds.; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; pp. 1096–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Li, J.; Fang, Y.; Lan, T.; Shi, X. Development of Quality Management System of Construction Engineering Testing Laboratory Based on Ontology. In ICCREM 2021: Challenges of the Construction Industry Under the Pandemic; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, Chicago, USA, 2021; pp. 486–493. [Google Scholar]

- Dwairi, S.; Mahdjoubi, L. Categorisation of Requirements in the Ontology-Based Framework for Employer Information Requirements (OntEIR). Buildings 2022, 12, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wu, P.; Wang, J.; Jiang, R.; Chen, M.; Wang, X. Developing a hybrid approach to extract constraints related information for constraint management. Autom. Constr. 2021, 124, 103563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.Y.; Li, C.; Petzold, F.; Tiong, R.L.K.; Yang, Y. Lifecycle framework for AI-driven parametric generative design in industrialized construction. Autom. Constr. 2025, 174, 106146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yang, G.; Li, H.; Jiang, A.; Zhu, X. Interactive self-contained compliant structure design supported by multi-objective knowledge inference. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2025, 2471078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ji, M.; Chen, J.; Wei, X.; Gu, X.; Tang, J. A large language model-based building operation and maintenance information query. Energy Build. 2025, 334, 115515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlapudi, J.; Valluru, P.; Menzel, K. Ontology Approach for Building Life Cycle Data Management. In Computing in Civil Engineering 2021; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2021; pp. 737–744. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Kim, H.; Kim, W.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.; Yu, J. Integration of ifc objects and facility management work information using Semantic Web. Autom. Constr. 2018, 87, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.T.; Ding, L.Y.; Love, P.E.D.; Luo, H.B. An ontological approach for technical plan definition and verification in construction. Autom. Constr. 2015, 55, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljamaa, E.; Peltomaa, I. Intensified construction process control using information integration. Autom. Constr. 2014, 39, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Wu, H.; Xiang, R.; Guo, J. Automatic Information Extraction from Construction Quality Inspection Regulations: A Knowledge Pattern-Based Ontological Method. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04021207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Jin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lv, J. Ontological Method for the Modeling and Management of Building Component Construction Process Information. Buildings 2023, 13, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knitt, H.; Ergin, E.; Jung, V.; Brell-Cokcan, S. Prozessmodellierung für den robotischen Zusammenbau im Stahlbau. Stahlbau 2025, 94, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinge, W.H.; Farghaly, K.; Mosleh, M.H.; Manu, P.; Cheung, C.M.; Osorio-Sandoval, C.A. BIM-based construction safety risk library. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q.T.; Lee, D.Y.; Park, C.S. A social network system for sharing construction safety and health knowledge. Autom. Constr. 2014, 46, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Tavakolan, M.; Zahriae, B. An Ontological Framework for Identification of Construction Resources Using BIM Information. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2018, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, T.; Trappey, A. Advanced Engineering Informatics—Philosophical and methodological foundations with examples from civil and construction engineering. Dev. Built Environ. 2020, 4, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Lv, X.; Gu, J.; Wu, Y. The Use of Weighted Euclidean Distance to Provide Assistance in the Selection of Safety Risk Prevention and Control Strategies for Major Railway Projects. Buildings 2024, 14, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirner, L.; Jung, V.; Oraskari, J.; Brell-Cokcan, S. Enhancing robotic steel prefabrication with semantic digital twins driven by established industry standards. Autom. Constr. 2024, 167, 105699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadee, A.A.; Martin, H.; Chadee, X.T.; Bahadoorsingh, S.; Olutoge, F. Root Cause of Cost Overrun Risks in Public Sector Social Housing Programs in SIDS: Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04023102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baboldashti, A.S.; Nik-Bakht, M. Taxonomy for Change Management Processes in Construction Projects. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2024, Des Moines, IA, USA, 20–23 March 2024; pp. 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Fischer, M.; Suh, M.J. Formal representation of cost and duration estimates for hard rock tunnel excavation. Autom. Constr. 2018, 96, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Mohamed, Y. A Framework for Visualizing Heterogeneous Construction Data Using Semantic Web Standards. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 8370931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, R.; Moscati, A.; Tan, H.; Johansson, P. Integration of manufacturers’ product data in BIM platforms using semantic web technologies. Autom. Constr. 2022, 144, 104630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.M.; Guo, B.H.W. FPSWizard: A web-based CBR-RBR system for supporting the design of active fall protection systems. Autom. Constr. 2018, 85, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Corry, E.; Curry, E.; Turner, W.J.N.; O’Donnell, J. Building performance optimisation: A hybrid architecture for the integration of contextual information and time-series data. Autom. Constr. 2016, 70, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Corry, E.; Horrigan, M.; Hoare, C.; Dos Reis, M.; O’Donnell, J. Building performance evaluation using OpenMath and Linked Data. Energy Build. 2018, 174, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, X. Data Quality Control Framework of an Intelligent Community from a Big Data Perspective. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Construction and Real Estate Management 2017, Guangzhou, China, 10 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eray, E.; Sanchez, B.; Haas, C. Usage of Interface Management System in Adaptive Reuse of Buildings. Buildings 2019, 9, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Roofigari-Esfahan, N.; Anumba, C. A Knowledge-Based Cyber-Physical System (CPS) Architecture for Informed Decision Making in Construction. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2018, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.; Xue, C.; Chang, W. China-aided conference buildings in developing countries: A mosaic analysis of database. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 1027–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Li, G.; Li, H. A Common Data Environment Framework Applied to Structural Life Cycle Assessment: Coordinating Multiple Sources of Information. Buildings 2025, 15, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhou, Y.C.; Lu, X.Z.; Lin, J.R. Knowledge-informed semantic alignment and rule interpretation for automated compliance checking. Autom. Constr. 2022, 142, 104524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupeikis, D.; Navickas, A.A.; Klumbyte, E.; Seduikyte, L. Comparative Study of Construction Information Classification Systems: CCI versus Uniclass 2015. Buildings 2022, 12, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroozfar, P.; Farr, E.R.P.; Zadeh, A.H.M.; Inacio, S.T.; Kilgallon, S.; Jin, R. Facilitating Building Information Modelling (BIM) using Integrated Project Delivery (IPD): A UK perspective. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 26, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Liu, B.; Wang, H. Construction of a Sustainability-Based Building Attribute Conservation Assessment Model in Historic Areas. Buildings 2022, 12, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, A.E.; Dikmen, I.; Birgonul, M.T.; Ercoskun, K.; Alten, S. A knowledge-based risk mapping tool for cost estimation of international construction projects. Autom. Constr. 2014, 43, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Tian, J.; Pan, X.; Shen, L. An Online Housing Reputation Assessment Framework Based on Text Mining and Visualization Technologies. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04023127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, D.; Yuan, J.; Donkers, A.; Liu, X. BIM-enabled semantic web for automated safety checks in subway construction. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Sepasgozar, S.M.E.; Ostwald, M.J. Knowledge-based semantic web technologies in the AEC sector. Autom. Constr. 2024, 167, 105686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ahn, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, D. Performance comparison of retrieval-augmented generation and fine-tuned large language models for construction safety management knowledge retrieval. Autom. Constr. 2024, 164, 105846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.; Love, P.E.D.; Porter, S.; Fang, W. Curating a domain ontology for rework in construction: Challenges and learnings from practice. Prod. Plan. Control 2023, 35, 2068–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L. Extracting Worker Unsafe Behaviors from Construction Images Using Image Captioning with Deep Learning-Based Attention Mechanism. J. Constr. Eng. 2022, 149, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Topic | Functional Objective | Data Type | Label Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Decision Support | BIM | Decision support for design and construction processes using BIM |

| 1 | Knowledge Accumulation and Reuse | Text + Image | Knowledge integration and retrieval using knowledge graphs and large language models, including vision-based applications |

| 2 | Quality and Regulatory Checking | Text | Information extraction and management from regulations, codes, and constraints |

| 3 | Sustainability and Structural Assessment | Image + Text | Structural damage detection and sustainability-oriented design assessment |

| 4 | Hazard Reasoning and Risk Assessment | Image | Image-based hazard assessment and risk interpretation |

| 5 | Quality and Regulatory Checking | BIM + Text | Regulatory compliance checking and safety knowledge mapping using BIM and textual data |

| 6 | Hazard Reasoning and Risk Assessment | BIM | Hazard identification and semantic reasoning based on BIM models |

| 7 | Knowledge Accumulation and Reuse | BIM + Sensor | Knowledge reuse for robotic inspection, bridge maintenance, and prefabricated construction |

| 8 | Hazard Reasoning and Risk Assessment | Sensor | Sensor-based environmental monitoring and cost-overrun risk assessment |

| 9 | Knowledge Accumulation and Reuse | BIM + Text | Information integration for BIM-based deconstruction planning and cost estimation |

| Functional Objective | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quality and Regulatory Checking | Evaluating design and construction quality and ensuring compliance with relevant codes and standards | BIM-based compliance checking; automated quality inspection; text-based regulation analysis |

| Decision Support | Supporting project planning, resource allocation, and process optimization | Prefabrication constructability analysis; resource identification; energy system evaluation |

| Hazard Reasoning and Risk Assessment | Identifying hazards, predicting accidents, and supporting proactive risk assessment | Image-based hazard detection; BIM-based safety reasoning; sensor-driven monitoring |

| Knowledge Accumulation and Reuse | Structuring, managing, and reusing project information and expert knowledge | Knowledge graph–based project information management; LLM-based querying; robotic inspection frameworks |

| Sustainability and Structural Assessment | Evaluating structural performance and sustainability-related aspects | Structural damage detection; low-carbon design assessment; sustainable building conservation |

| Data Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| BIM | Structured spatial and locational data used for object property extraction, compliance checking, clash detection, design validation, and hazard recognition in construction projects |

| Text | Extraction of entities and relationships from accident reports, safety manuals, work logs, and technical documents to support hazard reasoning, regulatory compliance, and knowledge reuse |

| Image | Two-dimensional image–based object detection and recognition of worker status (e.g., PPE use, unsafe behavior), equipment position and utilization, and construction quality assessment, combined with ontology-based semantic reasoning linked to site activities and safety rules |

| Sensor | IoT-based spatiotemporal monitoring of worker localization, equipment operation, structural vibration, and environmental conditions to support real-time hazard assessment, often within digital twin platforms |

| Integration Approach | Definition | Examples | Related Topics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embedding-based Integration | Transforms ontological concepts and relations into vector embeddings that are incorporated into AI model training or inference. | Poincaré embeddings for hierarchical structures; Word2Vec/BERT embeddings of ontology terms | Topics 0, 5, 6, 7, 9 (BIM attribute embeddings, multimodal compliance checking, risk reasoning, robotic applications, deconstruction planning) |

| NLP-based Integration | Processes textual data (e.g., regulations, reports, manuals) using AI models that reference, generate, or leverage ontological structures. | LLM–ontology integration for contract analysis; named entity recognition (NER) with ontology mapping from regulatory documents | Topics 1, 2, 5, 9 (information integration and retrieval, regulation and code extraction, compliance checking, cost estimation documents) |

| Vision Model Integration | Analyzes image or video data using vision models (e.g., CNNs, YOLO) and maps recognition outputs to ontology concepts or incorporates ontological knowledge into vision pipelines. | Image-based hazard detection linked to ontology-driven semantic reasoning | Topics 1, 3, 4, 7 (vision–knowledge graph integration for hazard recognition, structural damage detection, image-based hazard assessment, robotic inspection) |

| Few-shot and Transfer Learning Integration | Exploits ontological class hierarchies or semantic structures to support transfer learning, few-shot learning, or fine-tuning in data-scarce environments. | Ontology-based class hierarchies used as semantic features for transfer learning | Topic 8 (sensor-based environmental monitoring and risk assessment in data-scarce settings) |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Integration | Employs ontology or knowledge graph structures as graph inputs to GNN architectures (e.g., GCN, GraphSAGE, GAT) for relational learning and inference. | Risk-factor relationship graphs analyzed using GNNs | Topics 6, 9 (BIM-based risk reasoning, IFC- and knowledge graph–based deconstruction planning and risk mapping) |

| Functional Roles | Definition |

|---|---|

| Situation Awareness | Semantic interpretation of worker positions, behaviors, equipment interactions, and procedural compliance to assess normal or abnormal site conditions in real time. |

| Quality Regulation Compliance | Structuring quality regulations within ontologies and mapping them to recognized objects and relationships to automatically determine conformity or non-conformity. |

| Hazard Identification | Identifying potential hazards from site objects, equipment, and environmental factors and mapping them onto ontology classes and attributes for structured representation. |

| Risk Assessment | Classifying identified hazards into risk levels (e.g., low, medium, high) using rule-based reasoning or probabilistic models. |

| Process Tracking | Mapping recognized objects and task activities to BIM- and process-oriented ontologies to infer progress status and completion levels of construction workflows. |

| Anomaly Detection | Detecting deviations from ontology-based models of normal workflows—such as sequence errors, bottlenecks, or delays—by comparing actual site observations against expected process patterns. |

| Approach | Representative Tools | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual | Protégé, OWL | High interpretability; strong domain alignment | Time- and labor-intensive; limited scalability |

| Automated | NLP pipelines, LLMs, Graph databases | Rapid development; scalable for large datasets | Reduced precision; limited domain-specific accuracy |

| Hybrid | Protégé combined with automated mapping modules | Balances manual reliability with real-time adaptability | Higher system complexity; increased integration overhead |

| Model Family | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| YOLO (all versions) | Real-time object detection; lightweight and efficient; widely applied to construction safety monitoring and process-related tasks |

| Mask R-CNN | Precise object segmentation and fine-grained spatial analysis; suitable for structural damage detection and object state monitoring |

| VRD (VTransE) | Extraction of inter-object relationships aligned with ontology structures; supports contextual reasoning and compliance assessment |

| Image Captioning (Attention CNN + RNN) | Generation of descriptive scene narratives; enables ontology-based rule matching and semantic interpretation |

| Others/Unspecified | Includes BLE-based semantic trajectory analysis for location-based awareness and studies where vision models were not explicitly specified but image data were used for semantic enrichment or training |

| Author(s) | Functional Role | Ontology Construction | Image Recognition Models | Integration Approach | Description | Observed Outcomes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee & Yu [21] | Regulation and Standards Compliance; Hazard Analysis | Manual | YOLO | Rule-Based Reasoning Integration | Recognition outputs mapped to ontology rules for hazard reasoning | Reduced false positives; support for real-time hazard inference; enhanced situation awareness | Limited generalizability |

| Zheng et al. [24] | Process Monitoring | Manual | Not specified | Class Mapping Integration | Detection outputs mapped to a process ontology for workflow monitoring | Improved data interoperability; semantic reasoning for situation awareness | No direct accuracy gain; dependent on ontology quality |

| Fang et al. [26] | Regulation and Standards Compliance; Hazard Analysis | Hybrid | Mask R-CNN | Rule-Based Reasoning Integration | Ontology-based reasoning applied to validate compliance with predefined safety rules | Reduced false positives in hazard detection; strengthened semantic reasoning and situation awareness mIoU: 41.22%; Accuracy: 79.98% | Limited generalizability |

| Pfitzner et al. [22] | Process Monitoring | Automated | YOLO + GNN (post-reasoning) | Transfer & Embedding-Based Integration | Knowledge graph embeddings used for semantically informed feature learning | Enabled process monitoring; improved state classification accuracy Accuracy: +8–9% | Limited generalizability |

| Zhang et al. [25] | Hazard Analysis | Automated | YOLO | Rule-Based Reasoning Integration | Ontology-based evaluation of compliance and hazard classification | Reduced incorrect hazard associations; improved real-time relevance; enabled risk evolution tracking | No direct accuracy gain; dependent on ontology quality |

| Pfitzner et al. [46] | Process Monitoring | Automated | YOLO | Class Mapping Integration | Detection streams linked to ontology/knowledge graph for continuous semantic updates | Supported workflow monitoring; enriched semantic data | Limited generalizability |

| Pan et al. [31] | Process Monitoring | Automated | YOLO | Transfer & Embedding-Based Integration | Zero-shot label embeddings used to extend recognition beyond training classes | Supported workflow monitoring; improved recognition of construction entities Top-1 Accuracy: +30%; mAP: +19% | Proof-of-concept stage |

| Pfitzner et al. [76] | Process Monitoring | Automated | YOLO | Class Mapping Integration | Semantic enrichment applied to detection results | Supported workflow monitoring; mitigated misclassifications | No direct accuracy gain; dependent on ontology quality |

| Li et al. [19] | Regulation and Standards Compliance | Manual | VRD (VTransE) | Rule-Based Reasoning Integration | Relational recognition outputs mapped to ontology rules | Reduced false positives; improved hazard identification; enhanced semantic consistency Top-1 Accuracy: 49.91%; Recall@100: 49.13% | Proof-of-concept stage |

| Wu et al. [18] | Regulation and Standards Compliance; Hazard Analysis | Hybrid | YOLO | Rule-Based Reasoning Integration | Ontology reasoning applied to construction safety violation detection | Improved classification consistency; complemented semantic gaps | Proof-of-concept stage |

| Hamdan et al. [27] | Work and Situation Awareness | Hybrid | Mask R-CNN | Rule-Based Reasoning Integration | Ontology-based classification of hazard levels in real-time monitoring | Reduced manual effort; improved expert consistency; enabled damage progression tracking | Limited generalizability |

| Arslan et al. [28] | Work and Situation Awareness | Hybrid | BLE-based semantic trajectory | Preprocessing-Based Integration | Ontology-based semantic labels applied during preprocessing | Enabled unsafe movement detection; enriched trajectory semantics | Limited generalizability |

| Zeng et al. [29] | Work and Situation Awareness | Manual | Not specified | Class Mapping Integration | Ontology mapping used for semantic augmentation | Decision support for algorithm selection; improved hazard image retrieval precision | Limited generalizability |

| Pedro et al. [30] | Regulation and Standards Compliance | Hybrid | Not specified | Class Mapping Integration | Ontology applied for training and scenario evaluation | Automated data integration; improved accessibility of accident cases Post-test performance: +3–13% | No direct accuracy gain; dependent on ontology quality |

| Zhong et al. (2020) [8] | Hazard Analysis | Hybrid | YOLO | Rule-Based Reasoning Integration | Captioning and detection outputs mapped to ontology rules | Reduced false positives; real-time hazard inference; consistent semantic annotation | No direct accuracy gain; dependent on ontology quality |

| Pan et al. (2024) [32] | Work and Situation Awareness | Hybrid | Not specified | Rule-Based Reasoning Integration | Ontology reasoning layer supports site safety decision-making | Improved situational interpretation accuracy | Limited generalizability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.; Hwang, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, S. A Systematic Review of Ontology–AI Integration for Construction Image Recognition. Information 2026, 17, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010048

Kim Y, Hwang J, Lee S, Lee S. A Systematic Review of Ontology–AI Integration for Construction Image Recognition. Information. 2026; 17(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Yerim, Jihyun Hwang, Seungjun Lee, and Seulki Lee. 2026. "A Systematic Review of Ontology–AI Integration for Construction Image Recognition" Information 17, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010048

APA StyleKim, Y., Hwang, J., Lee, S., & Lee, S. (2026). A Systematic Review of Ontology–AI Integration for Construction Image Recognition. Information, 17(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010048