4. Materials and Methods

This research aims to design and implement a specialized deep learning framework for the accurate and efficient detection of DDoS attacks targeting in-vehicle networks. The proposed models will be trained and validated using benchmark datasets, specifically the CIC-DDoS2019 [

45] dataset. Performance will be rigorously assessed against a comprehensive set of metrics, with a strong emphasis on recall to minimize false negatives, thereby ensuring robustness and reliability in the safety-critical context of autonomous vehicle infrastructure.

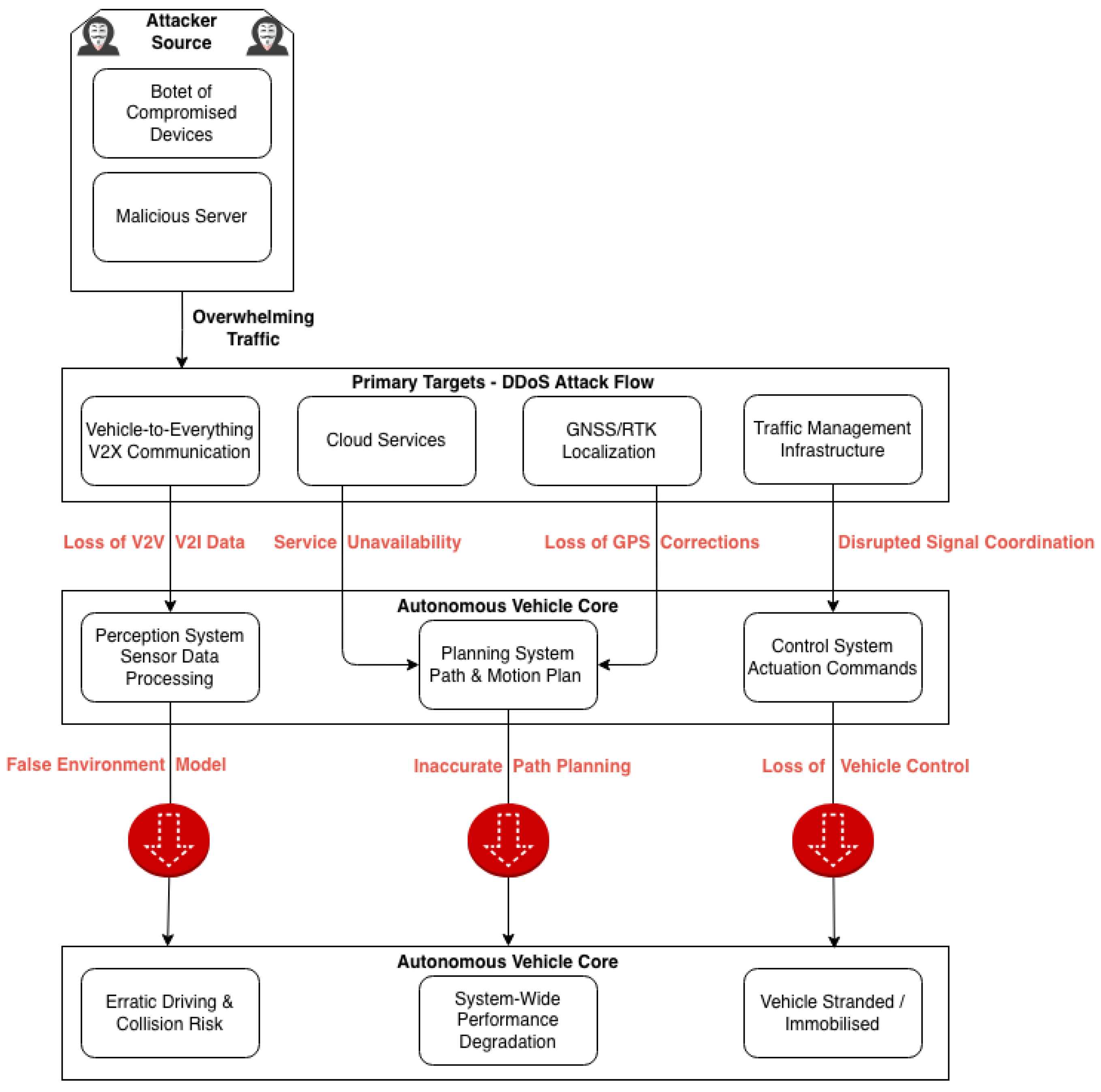

The proposed system architecture employs a Federated Learning (FL) framework for an Intrusion Detection System (IDS) designed to protect autonomous vehicles from three primary DDoS attack vectors: volumetric floods, state-exhaustion, and amplification attacks. The architecture consists of a central server and a fleet of autonomous vehicles. Each vehicle collects network traffic data from its internal sensors and systems. These data are preprocessed locally by the vehicle’s computing unit to train a deep learning model specifically tailored to recognize one type of DDoS attack. Consequently, each vehicle develops a localized model capable of periodically detecting its assigned attack type without sharing raw data, as shown in

Figure 2.

Our framework leverages active learning to maximize data efficiency, with each client selecting the most informative samples for local training. The core federated learning cycle involves clients computing model gradients on their local data and transmitting these updates to a central server. The server aggregates the updates to generate a refined global model, which is then redistributed to the client vehicles.

This iterative process converges on a powerful, globally trained IDS. The final model is deployed on each vehicle to perform real-time detection of all three DDoS attack types. Upon detection, vehicles generate an immediate alert to the central server for incident response.

Our methodology begins by establishing a throughput threshold to differentiate between benign operational traffic and potential DDoS attack scenarios. The data then undergoes a rigorous preparation phase, which includes feature normalization and an optimized selection process to retain the most discriminative inputs for model training.

We leverage a suite of deep learning architectures, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), to capture both spatial and temporal patterns in network traffic. To maximize data efficiency and privacy, we integrate these models within a federated learning framework, augmented with active learning. This allows for decentralized training across vehicle nodes and iterative model refinement by selecting the most informative data samples.

Model efficacy is rigorously quantified using a standard set of metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score and false positive rate. This comprehensive evaluation provides a multifaceted view of performance and serves as the definitive criterion for selecting the optimal model for deployment.

Figure 3 depicts the architecture of our proposed system, which leverages a synergy of Deep Learning (DL), Federated Learning and Active Learning to achieve robust and efficient DDoS detection.

This study utilizes the CIC-DDoS2019 dataset, a comprehensive benchmark provided by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity. The dataset contains over 14,000 meticulously labeled instances of both benign and malicious network traffic. Its key strength lies in the diversity of its captured DDoS attacks, which includes major categories such as UDP Flood, TCP Flood, and HTTP Flood, each further subdivided into numerous subtypes to model a wide spectrum of real-world attack vectors.

This granularity, coupled with a similarly varied set of normal traffic profiles, makes CIC-DDoS2019 particularly advantageous for developing robust machine learning-based intrusion detection systems. The dataset’s breadth directly addresses the critical challenge of minimizing false positives by ensuring models are exposed to a rich tapestry of normal behavior, thereby fostering the creation of detectors that accurately discriminate between legitimate traffic and attacks.

Table 3 shows a detail of the used data set.

Data preprocessing and exploratory analysis are foundational to our modeling pipeline. This phase involves a comprehensive reformatting of the dataset and a rigorous examination of its variables to inform an effective modeling strategy. Based on the insights gained, we pursued a dual-classification approach to evaluate detection performance comprehensively. The study was conducted using both binary classification (normal vs. attack) and multi-class classification (identifying specific attack types), following a consistent data processing and evaluation workflow for both.

Data preprocessing is a critical stage in the machine learning pipeline, essential for transforming raw data into a suitable format for model training. Real-world datasets often contain noise, inconsistencies, and artifacts such as missing values, infinite numbers, and outliers that can significantly degrade model performance and generalizability if left unaddressed. The primary goal of preprocessing is to mitigate these issues to ensure the development of robust and reliable models.

This study implements a comprehensive preprocessing procedure, which includes:

Data Cleaning: To ensure data integrity and model compatibility, we implemented a rigorous data cleaning procedure. First, all infinite values were replaced with NaN to standardize missing data representation. Subsequently, any row containing a NaN value was removed via listwise deletion to create a complete-case dataset. This step is critical, as the presence of missing or infinite values can lead to numerical instability and training failures in machine learning models.

Furthermore, we removed several metadata and identifier columns that do not contribute to the discriminative power of a DDoS detection model. The dropped features include Unnamed: 0, Flow ID, Source IP, Source Port, Destination IP, Destination Port, SimilarHTTP, and Timestamp. Their exclusion prevents the model from learning non-generalizable patterns based on unique identifiers or transient connection metadata, thereby improving its ability to generalize to new, unseen network flows.

Encoding: In this preprocessing step, the target labels were encoded to facilitate both binary and multi-class classification. For the binary classification task, the LabelEncoder from the scikit-learn library was employed to transform the labels into a binary format, where 1 represents any DDoS attack and 0 represents benign traffic. For the subsequent multi-class classification task, the same encoder was used to assign a unique integer to each specific attack type (e.g., UDP flood, TCP flood), while benign traffic was maintained as a separate class.

Handling Class Imbalance: Prior to model training, we analyzed the distribution of our target variables. As illustrated in the figure below, we observed a significant class imbalance across all classification tasks. This includes the binary classification scenarios (e.g., Benign vs. UDP Flood, Benign vs. SYN Flood) and the multi-classification scenario for Amplification attacks (e.g., Benign, DNS, NTP).

To address this, we employed the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE). SMOTE mitigates class imbalance by generating synthetic instances of the minority classes through interpolation between existing, neighboring minority samples. This process creates a more balanced training dataset, which is crucial for preventing model bias toward the majority class. Consequently, the use of SMOTE helps to alleviate overfitting, improves the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data, and leads to more robust overall performance.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the visualization of labels before and after preprocessing.

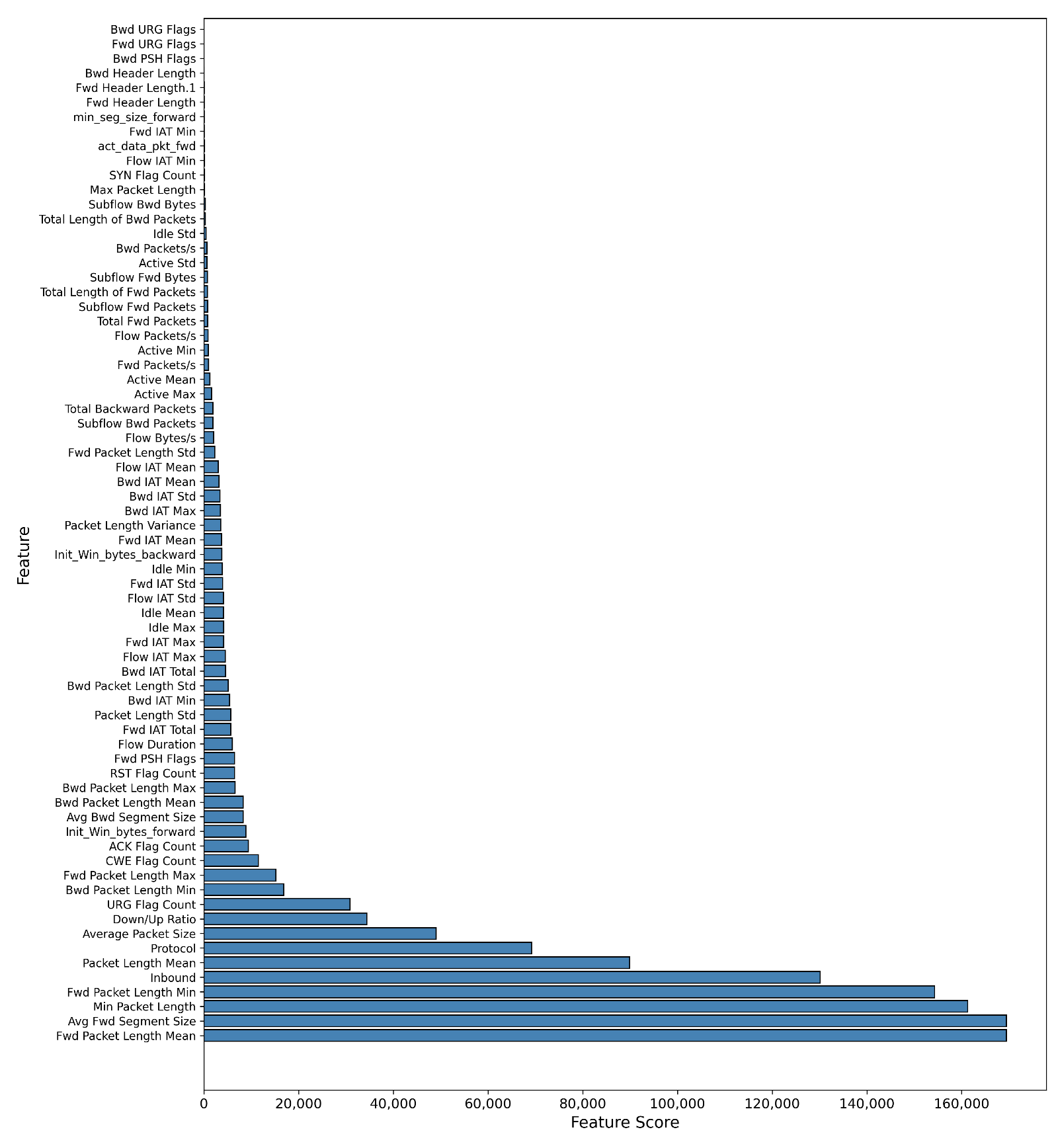

Feature Selection: To address the high dimensionality of the dataset, we implemented a feature selection step using the SelectKBest method with the f_classif scoring function from scikit-learn. This approach identifies the ’K’ most statistically significant features for our classification task, which improves model efficiency and performance. The selected features for each dataset are shown in the accompanying

Table 4.

Standardization/Normalization: Prior to model training, we implemented a critical data preprocessing pipeline to ensure robust and generalizable results. This involved two key steps: data scaling and dataset splitting.

First, we applied standardization (Z-score normalization) to scale all numerical features. This process transforms the data to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, ensuring that all input features contribute equally to the model’s learning process without being biased by their original scales. This leads to more stable convergence during training and improved model performance.

Subsequently, the entire dataset was partitioned into dedicated subsets for training and evaluation. We employed a standard hold-out validation strategy, allocating 80% of the data for training the models and reserving the remaining 20% as an unseen test set. This strict separation guarantees that the final evaluation reflects the model’s true ability to generalize to new, unseen data.

Models Architecture

This study implements and evaluates three distinct deep learning architectures, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), for the classification of DDoS attacks, including volumetric, state-exhaustion and amplification-based attacks.

Each model is structured with input, hidden, and output layers. The input layer receives the preprocessed features, which are appropriately reshaped to suit each architecture. Specifically, CNNs require a 2D structure for spatial feature extraction, while RNNs expect a sequential format to model temporal dependencies. The hidden layers across all models predominantly use the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function to introduce non-linearity and mitigate the vanishing gradient problem.

The configuration of the output layer is task-dependent. For binary classification (e.g., benign vs. attack), the output layer consists of a single neuron with a sigmoid activation function, which outputs a value between 0 and 1. A prediction threshold of 0.5 is used to discriminate between classes. For multi-class classification (e.g., identifying specific attack types), the output layer utilizes a softmax activation function. This function assigns a probability to each class, and the class with the highest probability is selected as the prediction.

All models were compiled using the Adam optimizer for efficient gradient-based learning. The loss function was selected according to the task: binary cross-entropy for binary classification and sparse categorical cross-entropy for multi-class classification. To enhance generalization and prevent overfitting, we integrated dropout layers into the models and employed an early stopping callback to halt training when validation performance ceased to improve.

DDoS classification based on CNN

The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture is designed to hierarchically extract spatial features from the input data. It is composed of an input layer, a sequence of convolutional blocks (convolution, activation, pooling), fully connected layers, and an output layer.

The process begins with convolutional layers, which apply a set of learnable filters to the input to detect local patterns and create feature maps. These maps are then passed through an activation function (ReLU) to introduce non-linearity. Subsequently, pooling layers (e.g., Max Pooling) downsample the feature maps, reducing their spatial dimensions. This serves to decrease computational complexity, provide translational invariance, and help prevent overfitting.

The resulting features are then flattened into a one-dimensional vector and fed into fully connected (dense) layers. These layers perform high-level reasoning and ultimately connect to the output layer, which uses a sigmoid activation function for binary classification (’normal’ vs. ’DDoS attack’).

Figure 6 illustrates the DDoS attack classification process implemented using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN).

The implemented one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture is structured as follows:

Two Convolutional Blocks: The model begins with two 1D convolutional layers (Conv1D). The first layer employs 32 filters, and the second layer employs 64 filters. Each convolutional layer is followed by a 1D max-pooling layer with a pool size of 2 to reduce dimensionality and extract salient features.

Classification Head: The output from the final pooling layer is flattened into a one-dimensional vector. This vector is then fed into a fully connected (Dense) layer with 128 units and a ReLU activation function.

Regularization: To mitigate overfitting, a Dropout layer with a rate of 0.5 is applied after the dense layer.

Output Layer: The final layer is a Dense layer configured for the specific classification task:

1 unit with a sigmoid activation function for binary classification.

N units with a softmax activation function for multi-class classification (where N is the number of classes).

DDoS classification based on RNN

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are particularly effective for sequential data, as demonstrated in applications like handwriting and speech recognition. Their ability to learn temporal dependencies through backpropagation makes them well-suited for classifying time-series network traffic.

Figure 7 elucidates the DDoS attack classification process implemented using a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN).

A Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) was selected for this study due to its capacity to model temporal sequences, which is well-suited for analyzing the time-series nature of network traffic in our large-scale dataset.

We constructed a simple RNN architecture, culminating in an output layer configured for our classification task. To achieve optimal performance, we conducted a series of experiments to tune key hyperparameters.

A critical preprocessing step involved reshaping the data into a temporal format compatible with RNN input requirements. The training and test sets were transformed into 3D NumPy arrays of the shape (samples, timesteps, features). For our initial model, we defined this structure as (number_of_instances, 1, number_of_features), effectively treating each sample as a single timestep containing all features.

DDoS classification based on DNN

We constructed a Deep Neural Network (DNN) comprising an input layer, two hidden dense layers, and an output layer. Through an iterative process of hyperparameter tuning, we determined the optimal number of neurons for each layer. The final configuration employs 32 units in both the input and hidden layers.

Figure 5 illustrates the complete architecture of our DNN model.

Figure 8 depicts the DDoS attack classification process implemented using a Deep Neural Network (DNN).

Active Learning:

We integrated an active learning strategy with the three previously discussed models (CNN, DNN, and RNN), applying a consistent implementation across all architectures. While active learning is traditionally used to selectively label data from a large unlabeled pool, we repurposed its core principle for our fully labeled dataset. The rationale is that not all labeled instances contribute equally to a model’s learning; some are redundant or less informative.

Therefore, our approach uses the active learning query strategy to iteratively select only the most informative data points from the entire labeled dataset. This creates a curated, high-value training subset. By training on this optimized subset, we aim to enhance model performance and increase computational efficiency, preventing the model from being hindered by non-informative examples.

Figure 9 outlines the active learning process.

Our approach adapts the principles of active learning for a fully labeled dataset. Unlike traditional methods that query an oracle to label new data, our method employs an uncertainty-based sampling strategy, specifically an entropy-based query, to identify the most informative instances within the existing labeled data. This strategy selects samples where the model’s predictions exhibit the highest uncertainty, as these represent the most challenging and pedagogically valuable examples for the learner.

The implemented workflow is as follows:

The dataset is initially split into training, validation, and test sets.

The model is trained for a single epoch on the current training set.

The model then performs inference on the entire dataset, and the predictive entropy for each instance is calculated.

Instances with the highest entropy, indicating maximum model uncertainty, are selected from the pool and added to the training set for the next iteration.

This process is repeated for a predefined number of cycles, progressively curating a training set composed of the most valuable data points. This forces the model to focus its learning effort on the most ambiguous and critical examples, thereby enhancing its discriminative capabilities and leading to more robust future predictions.

Federated learning

We employ a Federated Learning (FL) framework to enable collaborative training of intrusion detection models across multiple clients (e.g., vehicles or edge devices). This approach allows for the collective improvement of a global model to identify attack patterns without the need to centralize or disclose any private, raw data.

The process begins locally on each client:

Local Preprocessing: Each client preprocesses its own network traffic data, which involves cleaning, feature extraction, and scaling to prepare it for the chosen deep learning model (CNN, RNN, or DNN).

Local Training: The client then performs a training epoch on its local dataset. This involves using an optimization algorithm, typically a variant of Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), to compute an update to the model. Crucially, this update is in the form of gradients (the mathematical adjustments needed to minimize error), not the raw data itself.

Secure Aggregation: These gradient updates from all participating clients are sent to a central server.

Global Model Update: The server aggregates these gradients (e.g., by averaging) to update a global model, which is then redistributed to the clients for the next round of learning.

Figure 10 shows the federated learning process.

The federated training process, executed by the server using FLAD, is detailed in Algorithms 1 and 2. The corresponding local training process, executed by the clients using a DNN model with Active Learning, is outlined in Algorithm 3.

Client selection for each subsequent training round is managed implicitly by the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) strategy, implemented on the server side using the Flower (’Flwr’) framework.

| Algorithm 1 Global model for Federated learning |

- Require:

,

for in 1 to do for all in do end for if then else end if if then return end if end for return

|

| Algorithm 2 Select Clients for Next Round of Training |

- Require:

C: Set of available clients - Require:

K: Number of clients to select for each round - Require:

T: Number of communication rounds

- 2:

for

T

do Select K clients randomly or using a selection strategy - 4:

Send current global model parameters to selected clients for each selected client c do - 6:

Receive client-specific model updates from client c end for - 8:

Aggregate model updates: Update global model parameters: , where is the learning rate - 10:

end for

|

In the following, we present the mathematical formalization of the proposed federated and active learning framework for DDoS detection in vehicular networks. The formulation ensures collaborative learning while preserving data privacy and optimizing computational efficiency across participating vehicles.

- 1.

Problem Setup

Let be vehicular clients. Each client K has a local dataset where denotes the traffic class (benign or one of three DDoS types).

- 2.

Active Learning at Local Clients

At round

t, client

K selects an informative subset

via uncertainty sampling:

The local cross-entropy loss on this subset is:

- 3.

Federated Aggregation

Selected clients perform

E epochs of SGD, then transmit updates to the server. The global model is updated via weighted averaging:

- 4.

Detection Performance

The system’s efficacy is measured by the global false positive rate:

and the attack-type-specific recall:

| Algorithm 3 Local training procedure at client c |

- 1:

- 2:

Initialize training data - 3:

- 4:

Create copies of training data - 5:

if

then - 6:

- 7:

Compute batch size - 8:

end if - 9:

- 10:

Split data into batches - 11:

for epoch from 1 to do - 12:

Loop over epochs - 13:

for do - 14:

Loop over batches - 15:

- 16:

Update parameters - 17:

end for - 18:

end for - 19:

return

w - 20:

Return updated parameters to server

|

5. Evaluation and Results

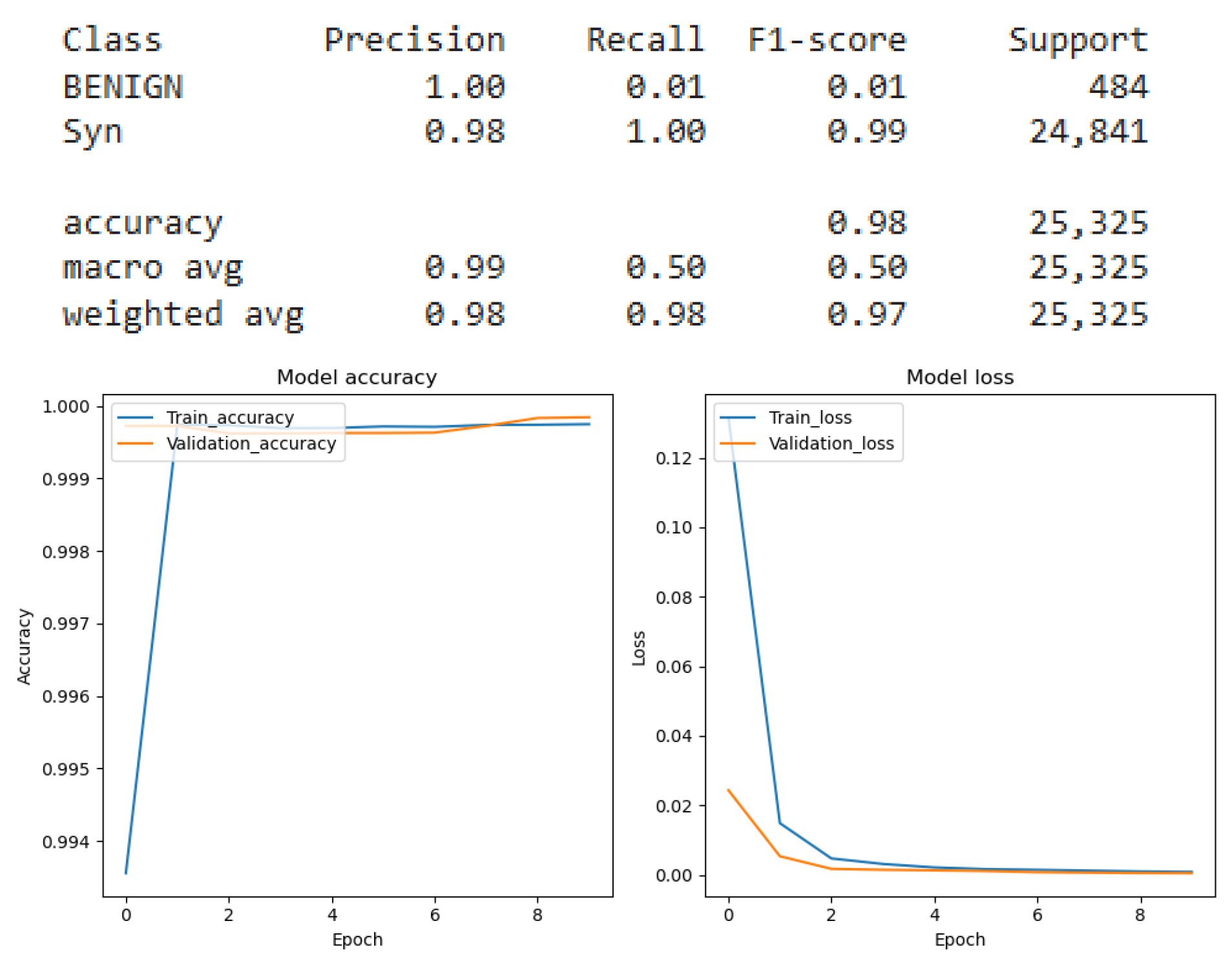

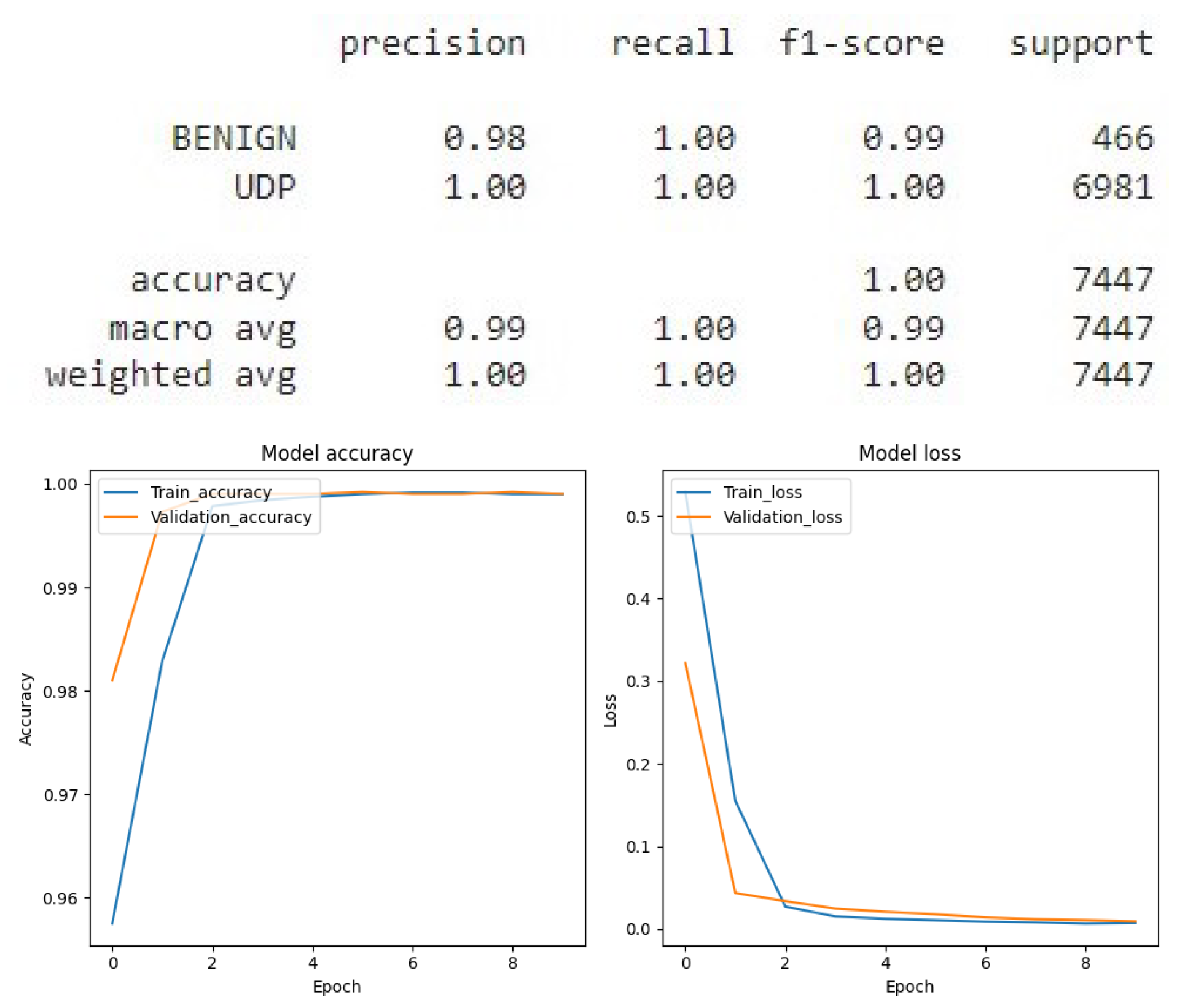

The primary objective of this research was to develop and evaluate a robust intrusion detection system capable of identifying multiple DDoS attack vectors namely volumetric, amplification, and state-exhaustion attacks. To this end, we implemented and compared a suite of deep learning architectures, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). Each model was rigorously trained and evaluated under two distinct classification paradigms: binary (benign vs. attack) and multi-class (identifying the specific attack type). Through extensive hyperparameter tuning, we optimized each model’s configuration. A detailed performance analysis, based on the experimental results from the test dataset, is provided in

Figure 11 which presents the results of the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) applied to the binary classification of SYN flags,

Figure 12 which presents the results of the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) applied to the binary classification of UDP protocol,

Figure 13 which provides the results of the multiclass classification analysis conducted using the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) model,

Figure 14 which presents the results of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) applied to the binary classification of SYN flags,

Figure 15 which presents the results of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) applied to the binary classification of UDP protocol,

Figure 16 which provides the results of the multiclass classification analysis conducted using the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model,

Figure 17 which presents the results of the Deep Neural Network (DNN) applied to the binary classification of SYN flags,

Figure 18 which presents the results of the Deep Neural Network (DNN) applied to the binary classification of UDP protocol and

Figure 19 which provides the results of the multiclass classification analysis conducted using the Deep Neural Network (DNN) model.

Our comparative analysis revealed that the DNN model delivered the best performance and adaptability for the IDS. We therefore focused on refining this model through active learning.

Figure 20 shows a comparative analysis of UDP classification performance using a Deep Neural Network (DNN), contrasting the results before and after the integration of Active Learning.

The impact of Active Learning on a Deep Neural Network (DNN) for SYN classification is evaluated in

Figure 21, which contrasts the model’s performance before and after its integration.

Figure 22 presents a comparative analysis of the DNN’s performance on multiclass classification before and after the implementation of Active Learning.

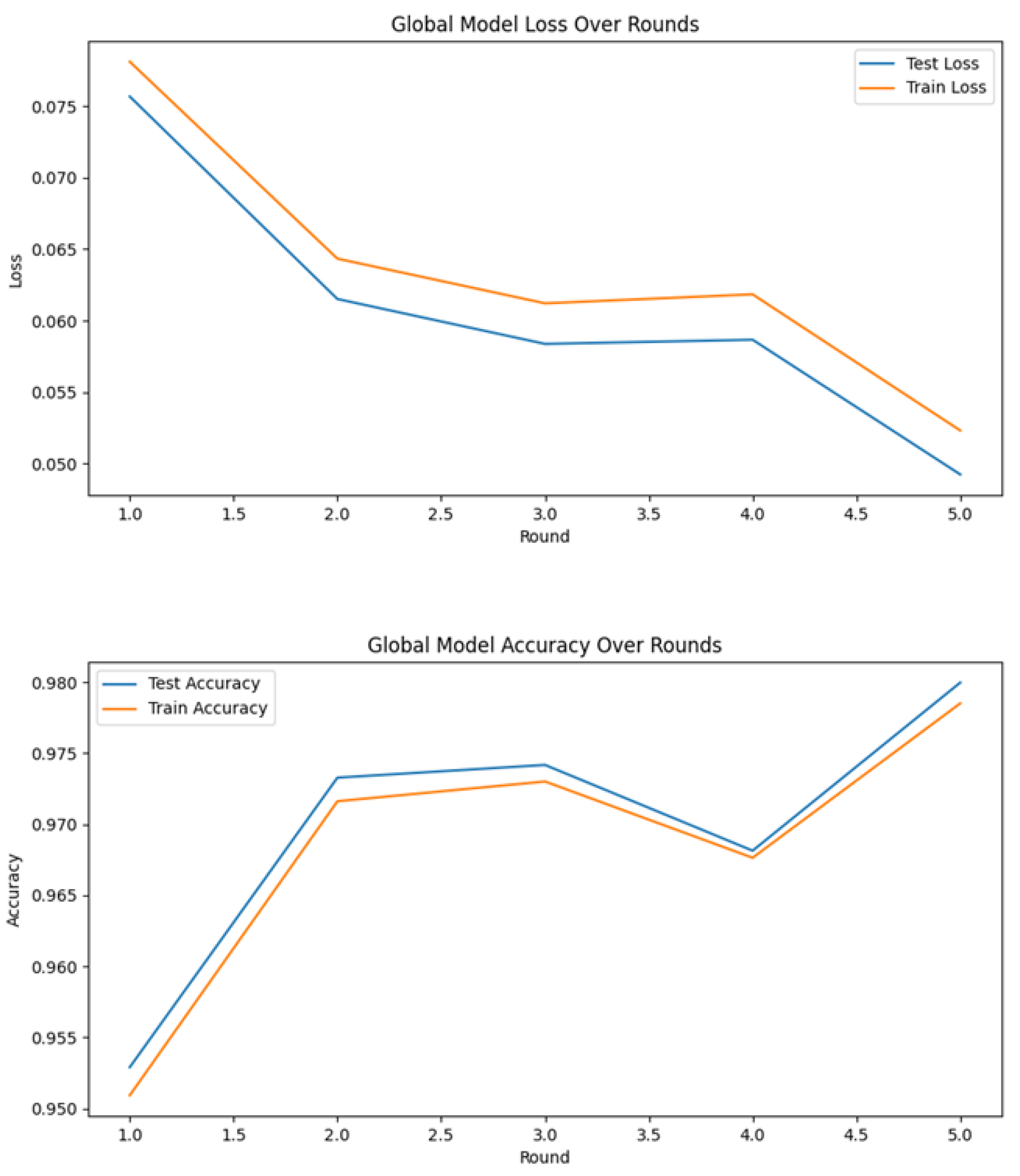

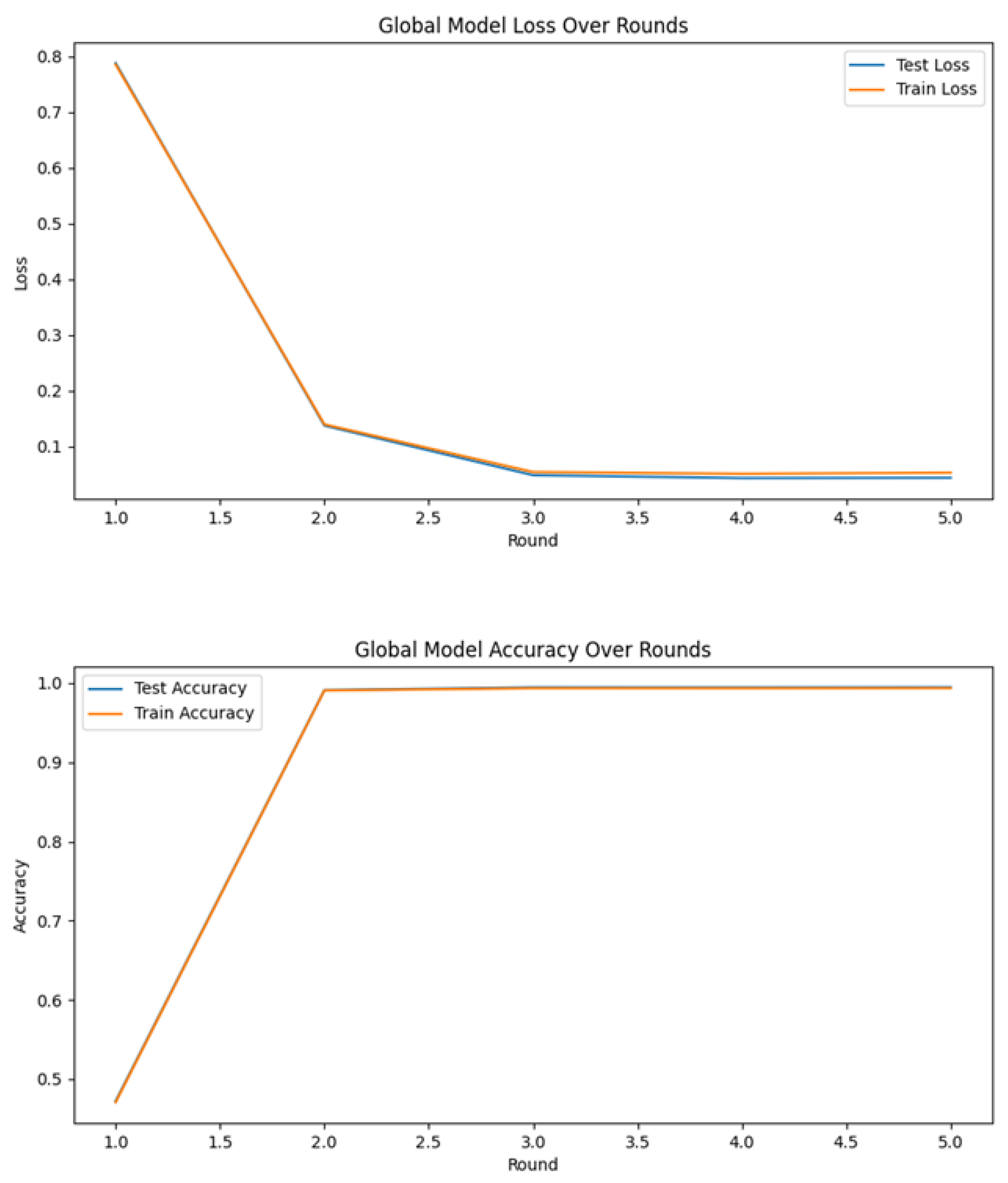

In the final phase, we deployed a federated learning framework using the DNN model, which demonstrated superior performance in our prior comparative analysis. This federated architecture, augmented with the active learning techniques previously described, further enhances the model’s efficacy. The system was trained to detect three primary DDoS attack types: Amplification, Volumetric, and State-Exhaustion. The results of this integrated approach are presented in the figure below.

Figure 23 presents the performance of the Deep Neural Network (DNN) within a Federated Learning framework, excluding the use of Active Learning.

Figure 24 shows the results of the Deep Neural Network (DNN) model that integrates both Federated Learning and Active Learning.

As depicted in

Figure 25, the global false alarm rate exhibits a consistent monotonic decrease across successive federated communication rounds, converging from an initial 5% to a stable 1%. This empirical trend demonstrates the efficacy of the federated learning process in collaboratively refining model parameters to minimize erroneous alerts and systematically improve overall network specificity.

This section details the evaluation metrics employed to assess the performance of our proposed intrusion detection system. A robust evaluation is critical for understanding a model’s real-world applicability, particularly in security contexts where different types of errors carry different consequences. We report on standard classification metrics, including precision, recall, and F1-score to provide a comprehensive view of model efficacy.

Precision quantifies the reliability of a model’s positive predictions. It is defined as the proportion of correctly identified DDoS attacks (

True Positives) among all instances the model classified as an attack (both

True Positives and

False Positives). A high precision indicates a low rate of false alarms. Precision is calculated as follows:

Recall (or Sensitivity) measures the model’s ability to detect all actual DDoS attacks. It is defined as the proportion of actual DDoS attacks that were correctly identified. A high recall indicates that the model misses few attacks.

Recall is calculated as:

F1-

Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances the trade-off between the two. It is especially useful when dealing with imbalanced datasets. The

F1-

score is calculated as:

False Positive Rate measures the percentage of legitimate/normal network traffic that your system incorrectly flags as a DDoS attack.

Accuracy measures the overall correctness of the model across all classes. However, it can be a misleading metric on imbalanced datasets where one class (e.g., benign traffic) significantly outnumbers the other (e.g., attack traffic).

The efficacy of the proposed system is evaluated through a comparative analysis with existing literature, as detailed in

Table 5.

Algorithm 1 details the global federated learning model. The key factors affecting its computational complexity are the number of participating clients (vehicles) K, the size of local datasets , the number of model parameters W, and the total communication rounds T. Each client performs local training on its dataset, which requires approximately **W floating-point operations, where is the number of local epochs. Therefore, the overall computational complexity for Algorithm 1 can be expressed as O(T*K***W).

Algorithm 2, which handles client selection and model aggregation, operates over T communication rounds. Selecting K clients and aggregating their model updates W in each round results in a complexity of O(T*K*W). Algorithm 3 governs the active learning cycles performed locally by each client. Within each of the active learning cycles, a client processes a subset where of its dataset to compute predictions and update the model. This yields a per-client complexity of O(*W*). Collectively, all components of the proposed framework scale linearly with respect to the number of clients, local epochs, dataset size, and model parameters, confirming an overall polynomial time complexity. This demonstrates the computational scalability of the proposed approach for large-scale, multi-vehicle autonomous systems.

In our experiments, the local training phase at each client required approximately 25 s per communication round. The inference phase, processing the complete CIC-DDoS2019 test dataset, took about 0.01 s, highlighting the efficiency of the deployed global model.

These results are comparable to state-of-the-art deep learning-based IDS approaches. For instance, the study reported training times between 6 and 29 s for CNN-BiLSTM models on the same dataset, with their best-performing model requiring 29 s. Another study achieved an inference latency of 0.509 ms per network frame using a deep neural network. Comparative work by [

51] demonstrated that a Bayesian-optimized decision tree classifier required 25.851 s for training, while KNN and SVM required 68.632 and 592.97 s, respectively; their decision tree model also processed the complete test dataset in approximately 0.01 s. This comparative analysis confirms that the runtime performance of our federated and active learning-integrated framework remains competitive without compromising its advantages in privacy preservation and collaborative learning.