Automated Severity and Breathiness Assessment of Disordered Speech Using a Speech Foundation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

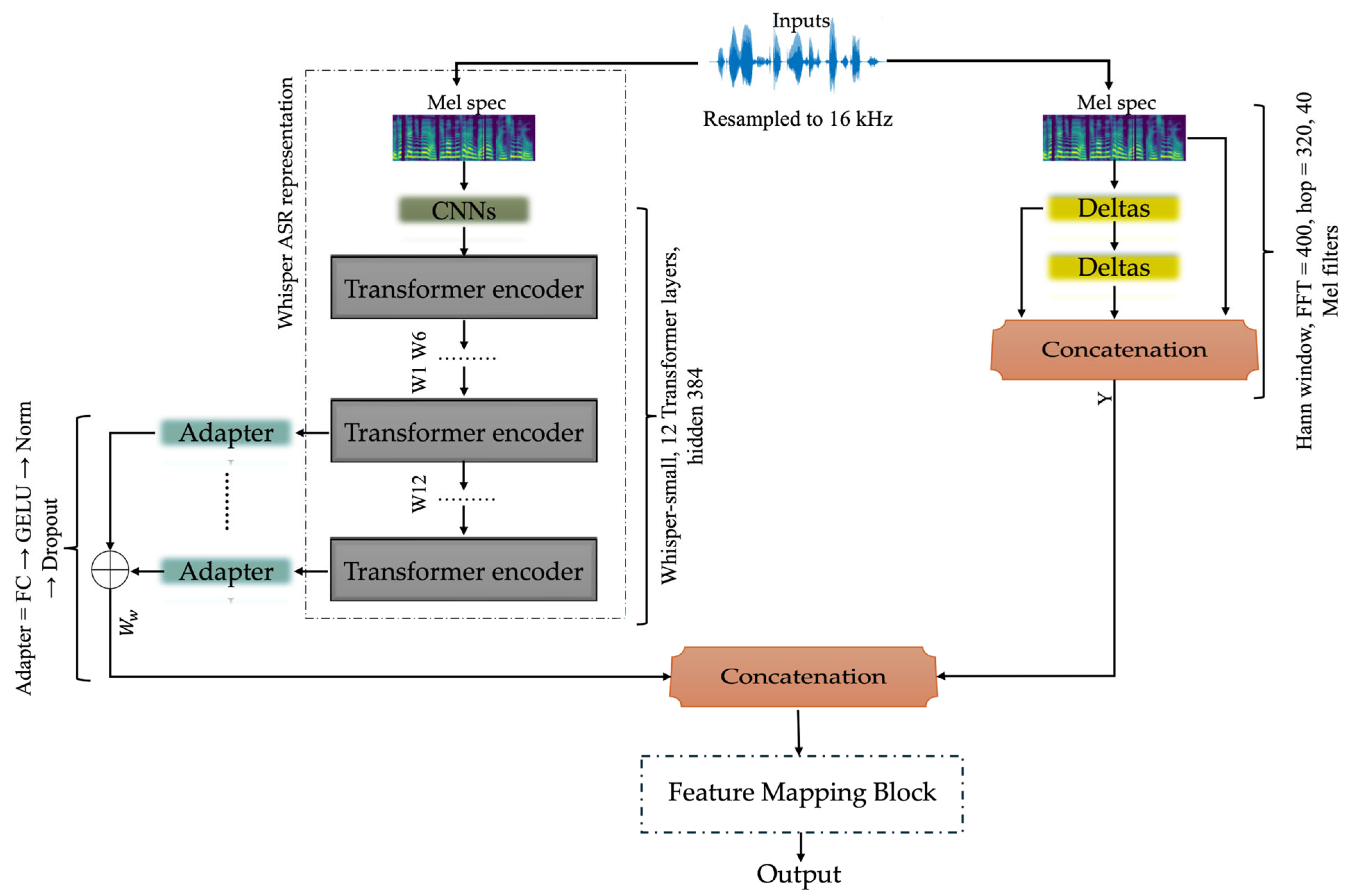

2. Proposed Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Datasets

3.2. Input Data

3.3. Training Setup

3.4. Statistical Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Training and Validation Results

4.2. Descriptive Data and Analyses

4.3. Linear Regression and Correlational Analyses

4.4. Bland–Altman Analyses

4.5. Ablational Analyses

4.6. Generalization to an Unseen Dataset

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASR | Automatic Speech Recognition |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| SQ | Speech Quality |

| SI | Speech Intelligibility |

| SFMs | Speech Foundation Models |

| CPP | Cepstral Peak Prominence |

| AVQI | Acoustic Voice Quality Index |

| CAPE-V | Consensus Auditory-Perceptual Evaluation of Voice |

| GRBAS | Grade, Roughness, Breathiness, Asthenia, and Strain |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| CPC2 | Clarity Prediction Challenge 2 |

| SSL | Self-Supervised Learning |

| SAFN | Sequential-Attention Fusion Network |

| FC | Fully Connected |

| GAP | Global Average Pooling |

| PVQD | Perceptual Voice Qualities Database |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| BLSTM | bidirectional long short-term memory |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| PESQ | Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality |

| MOS | Mean Opinion Score |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| RF | Random Forest |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| GELU | Gaussian Error Linear Unit |

| MHA | Multi-Head Attention |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

References

- Barsties, B.; De Bodt, M. Assessment of voice quality: Current state-of-the-art. Auris Nasus Larynx 2015, 42, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiman, J.; Gerratt, B.R. Perceptual Assessment of Voice Quality: Past, Present, and Future. Perspect. Voice Voice Disord. 2010, 20, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboi, T.; Watanabe, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Ohdake, R.; Yoneyama, N.; Hara, K.; Nakamura, R.; Watanabe, H.; Senda, J.; Atsuta, N.; et al. Distinct phenotypes of speech and voice disorders in Parkinson’s disease after subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2015, 86, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi, T.; Watanabe, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Ohdake, R.; Hattori, M.; Kawabata, K.; Hara, K.; Ito, M.; Fujimoto, Y.; Nakatsubo, D.; et al. Early detection of speech and voice disorders in Parkinson’s disease patients treated with subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation: A 1-year follow-up study. J. Neural Transm. 2017, 124, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Le, D.; Zheng, W.; Singh, T.; Arora, A.; Zhai, X.; Fuegen, C.; Kalinli, O.; Seltzer, M.L. Evaluating User Perception of Speech Recognition System Quality with Semantic Distance Metric. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2110.05376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidaka, S.; Lee, Y.; Nakanishi, M.; Wakamiya, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Kaburagi, T. Automatic GRBAS Scoring of Pathological Voices using Deep Learning and a Small Set of Labeled Voice Data. J. Voice 2025, 39, 846.e1–846.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, R.D. Hearing and Believing. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 1996, 5, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D.D.; Hillman, R.E. Voice assessment: Updates on perceptual, acoustic, aerodynamic, and endoscopic imaging methods. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2008, 16, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, K.F. Clinical Use of the CAPE-V Scales: Agreement, Reliability and Notes on Voice Quality. J. Voice 2025, 39, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryn, Y.; Roy, N.; De Bodt, M.; Van Cauwenberge, P.; Corthals, P. Acoustic measurement of overall voice quality: A meta-analysisa. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2009, 126, 2619–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, J.A.; Moro-Velázquez, L.; Mendes-Laureano, J.; Castellanos-Dominguez, G.; Godino-Llorente, J.I. Emulating the perceptual capabilities of a human evaluator to map the GRB scale for the assessment of voice disorders. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2019, 82, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryn, Y.; Weenink, D. Objective Dysphonia Measures in the Program Praat: Smoothed Cepstral Peak Prominence and Acoustic Voice Quality Index. J. Voice 2015, 29, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; Tan, X.; Zhao, S.; Soong, F.; Li, X.-Y.; Qin, T. MBNET: MOS Prediction for Synthesized Speech with Mean-Bias Network. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021—2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–11 June 2021; pp. 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Zezario, R.E.; Fu, S.-W.; Chen, F.; Fuh, C.-S.; Wang, H.-M.; Tsao, Y. Deep Learning-Based Non-Intrusive Multi-Objective Speech Assessment Model With Cross-Domain Features. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2023, 31, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Williamson, D.S. An Attention Enhanced Multi-Task Model for Objective Speech Assessment in Real-World Environments. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 911–915. [Google Scholar]

- Zezario, R.E.; Fu, S.-W.; Fuh, C.-S.; Tsao, Y.; Wang, H.-M. STOI-Net: A Deep Learning based Non-Intrusive Speech Intelligibility Assessment Model. In Proceedings of the 2020 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), Auckland, New Zealand, 7–10 December 2020; pp. 482–486. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9306495 (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Fu, S.-W.; Tsao, Y.; Hwang, H.-T.; Wang, H.-M. Quality-Net: An End-to-End Non-intrusive Speech Quality Assessment Model based on BLSTM. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.05344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.-C.; Pawlicki, A.; Stamenovic, M. CCATMos: Convolutional Context-aware Transformer Network for Non-intrusive Speech Quality Assessment. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2022, Incheon, Republic of Korea, 18–22 September 2022; pp. 3318–3322. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Tan, K.; Ni, Z.; Manocha, P.; Zhang, X.; Henderson, E.; Xu, B. Torchaudio-Squim: Reference-Less Speech Quality and Intelligibility Measures in Torchaudio. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Shi, H.; Chu, C.; Kawahara, T. Enhancing Two-Stage Finetuning for Speech Emotion Recognition Using Adapters. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 11316–11320. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Chu, C.; Kawahara, T. Two-stage Finetuning of Wav2vec 2.0 for Speech Emotion Recognition with ASR and Gender Pretraining. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2023, ISCA, Dublin, Ireland, 20–24 August 2023; pp. 3637–3641. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Hu, D.; Shi, X.; He, J.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Toda, T.; Xu, X.; Hu, X. Semi-supervised Multimodal Emotion Recognition with Consensus Decision-making and Label Correction. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Multimodal and Responsible Affective Computing, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October 2023; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Kudo, H. Using Semi-supervised Learning for Monaural Time-domain Speech Separation with a Self-supervised Learning-based SI-SNR Estimator. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2023, ISCA, Dublin, Ireland, 20–24 August 2023; pp. 3759–3763. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; Zeng, W.; Chen, Y.; Qin, Y. Fine-Grained Disentangled Representation Learning For Multimodal Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 11051–11055. [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo, S.; Marxer, R. Speech Foundation Models on Intelligibility Prediction for Hearing-Impaired Listeners. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 1421–1425. [Google Scholar]

- Mogridge, R.; Close, G.; Sutherland, R.; Hain, T.; Barker, J.; Goetze, S.; Ragni, A. Non-Intrusive Speech Intelligibility Prediction for Hearing-Impaired Users Using Intermediate ASR Features and Human Memory Models. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 306–310. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.S.; Jovanovic, N.; Sung, C.K.; Doyle, P.C. A Scoping Review of Artificial Intelligence Detection of Voice Pathology: Challenges and Opportunities. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2024, 171, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhu, P.; Qiu, W.; Guo, J.; Li, Y. Deep learning in automatic detection of dysphonia: Comparing acoustic features and developing a generalizable framework. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2023, 58, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.A.; Rosset, A.L. Deep Neural Network for Automatic Assessment of Dysphonia. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.12957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Tsuboi, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Nakatsubo, D.; Maesawa, S.; Saito, R.; Katsuno, M.; Kudo, H. Developing vocal system impaired patient-aimed voice quality assessment approach using ASR representation-included multiple features. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.12279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Woerd, B.; Chen, Z.; Flemotomos, N.; Oljaca, M.; Sund, L.T.; Narayanan, S.; Johns, M.M. A Machine-Learning Algorithm for the Automated Perceptual Evaluation of Dysphonia Severity. J. Voice 2023, 39, 1440–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Tseng, W.-H.; Chen, L.-C.; Tan, C.-T.; Tsao, Y. Lightly Weighted Automatic Audio Parameter Extraction for the Quality Assessment of Consensus Auditory-Perceptual Evaluation of Voice. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 6–8 January 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. Mathematical Analysis and Performance Evaluation of the GELU Activation Function in Deep Learning. J. Math. 2023, 2023, 4229924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, P.R. Perceptual Voice Qualities Database (PVQD): Database Characteristics. J. Voice 2022, 36, 875.e15–875.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensar, B.; Searl, J.; Doyle, P. Stability of Auditory-Perceptual Judgments of Vocal Quality by Inexperienced Listeners. In Proceedings of the American Speech and Hearing Convention, Seattle, WA, USA, 5–7 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Component | Layer/Block | Key Parameters | Output Dimension | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Audio waveform | 16 kHz | — | Resampled to 16 kHz |

| Mel-Spectrogram | STFT (Hann) | FFT = 400, hop = 320, 40 Mel filters | 40 × T | Used for deltas |

| Delta Features | 1st & 2nd order | — | 120 × T | Concatenated to Mel |

| ASR Encoder | Whisper-small | 12 Transformer layers, hidden 384 | 384 × T | Pre-trained, not frozen |

| Adapters (×6) | FC (384 → 128) → GELU → LayerNorm → Dropout (0.1) | 6 learnable weights (softmax normalized) | 128 × T | Fuse multi-depth features |

| Fusion Block | Concatenation | Whisper + Mel + Deltas | (128 + 120) × T | Combined representation |

| SAFN (Feature Mapping Block) | 3 × Uni-LSTM (360 → 128, dropout 0.3) | +2 MHA (128 dim, 16 heads), FFN (128 → 256 → 128) | 128 × T | Temporal context modeling |

| Output Head | FC (128 → 1) → Sigmoid → Global Avg Pooling | — | 1 | Utterance-level quality score |

| Loss Function | MAE | — | — | Regression loss |

| Optimizer | AdamW | lr = 5 × 10−6, weight decay = 1 × 10−4 | — | ReduceLROnPlateau (f = 0.5, p = 4) |

| Training | 200 epochs | batch = 1 | Pretrained modules unfrozen | |

| Hardware | RTX 3080 Ti (10,240 CUDA cores), 32 GB RAM | — | — | PyTorch ≥ 2.0 (2.5.1+cu121) |

| Method | CAPE-V Severity | CAPE-V Breathiness | Trainable Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson r (95% CI) | Spearman ρ (95% CI) | RMSE | Pearson r (95% CI) | Spearman ρ (95% CI) | RMSE | ||

| Sentence Level: | |||||||

| Proposed | 0.8810 (0.8504, 0.9042) | 0.7652 (0.7024, 0.8161) | 0.1335 | 0.9244 (0.9040, 0.9401) | 0.8095 (0.7580, 0.8515) | 0.1118 | 242,423,655 |

| Dang et al. [30] | 0.8784 (0.8446, 0.9017) | 0.7648 (0.7017, 0.8166) | 0.1423 | 0.9155 (0.8924, 0.9328) | 0.8217 (0.7760, 0.8587) | 0.1159 | 336,119,692 |

| Dang et al. [30], Ablated | 0.8685 (0.8351, 0.8946) | 0.7560 (0.6942, 0.8073) | 0.1386 | 0.9104 (0.8856, 0.9290) | 0.8014 (0.7515, 0.8421) | 0.1216 | 241,177,500 |

| CPP (dB) | −0.7468 (−0.6935, −0.7890) | −0.6554 (−0.5816, −0.7217) | 0.1835 | −0.7577 (−0.7050, −0.7978) | −0.6223 (−0.5381, −0.6940) | 0.1665 | |

| HNR (dB) | −0.4916 (−0.3936, −0.5793) | −0.3649 (−0.2635, −0.4591) | 0.2402 | −0.4898 (−0.3787, −0.5873) | −0.2367 (−0.1196, −0.3454) | 0.2225 | |

| Talker Level: | |||||||

| Proposed | 0.9092 (0.8463, 0.9437) | 0.8062 (0.6416, 0.8953) | 0.1189 | 0.9394 (0.8880, 0.9654) | 0.8621 (0.7402, 0.9315) | 0.1029 | |

| Dang et al. [30] | 0.9034 (0.8327, 0.9413) | 0.8042 (0.6484, 0.8943) | 0.1286 | 0.9352 (0.8828, 0.9623) | 0.8645 (0.7587, 0.9281) | 0.1060 | |

| Dang et al. [30], Ablated | 0.9000 (0.8257, 0.9403) | 0.8110 (0.6640, 0.8988) | 0.1237 | 0.9342 (0.8823, 0.9623) | 0.8438 (0.7242, 0.9172) | 0.1111 | |

| Benjamin et al. [31] * | 0.8460 | - | 0.1423 | - | - | - | |

| CPP (dB) | −0.8489 (−0.7487, −0.9048) | −0.7512 (−0.5896, −0.8530) | 0.1458 | −0.8576 (−0.7662, −0.9135) | −0.6933 (−0.4865, −0.9135) | 0.1307 | |

| HNR (dB) | −0.5330 (−0.2758, −0.7142) | −0.3785 (−0.1199, −0.5952) | 0.2333 | −0.5296 (−0.2232, −0.7275) | −0.2161 (−0.0792, −0.4881) | 0.2156 | |

| Structure | Pearson r (Breathiness) |

|---|---|

| With proposed structure | 0.9244 |

| The proposed structure with LSTM fusion model | 0.9031 |

| The proposed structure without Mel-spectral + deltas stream | 0.8993 |

| The proposed model with three adapters in the last three ASR encoder block | 0.9026 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ashkanichenarlogh, V.; Hassanpour, A.; Parsa, V. Automated Severity and Breathiness Assessment of Disordered Speech Using a Speech Foundation Model. Information 2026, 17, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010032

Ashkanichenarlogh V, Hassanpour A, Parsa V. Automated Severity and Breathiness Assessment of Disordered Speech Using a Speech Foundation Model. Information. 2026; 17(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleAshkanichenarlogh, Vahid, Arman Hassanpour, and Vijay Parsa. 2026. "Automated Severity and Breathiness Assessment of Disordered Speech Using a Speech Foundation Model" Information 17, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010032

APA StyleAshkanichenarlogh, V., Hassanpour, A., & Parsa, V. (2026). Automated Severity and Breathiness Assessment of Disordered Speech Using a Speech Foundation Model. Information, 17(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010032