Abstract

The adoption of e-government services in Small Island Developing Nations (SIDNs) aims to enhance public service efficiency, inclusiveness, and quality. However, e-government service development in SIDNs faces some significant constraints, including limited resources, geographical isolation, low digital literacy levels, and inadequate technological infrastructure. This study investigates value co-creation approaches in e-government service, aiming to identify specific value co-creation processes and methods to support sustainable e-government initiatives in SIDN settings. The study applies a qualitative approach; based on the thematic analysis of interviews with government stakeholders, it identifies contextual factors and conditions that influence e-government value co-creation processes in SIDNs and strategies for sustainable e-government service value co-creation. This study contributes a value co-creation framework that applies participatory design, agile development, collaborative governance, socio-technical thinking, and technology adaptation as methods for the design and implementation of flexible and inclusive e-government services that are responsive to local needs, resilient to challenges, and sustainable over time. The framework can be used by policymakers and practitioners to facilitate sustainable digital transformation in SIDNs through collaborative governance, active participation, and civic engagement with innovative technologies.

1. Introduction

Small Island Developing Nations (SIDNs) are developing nations that are recognised as being at a particular risk due to their specific social, economic, and environmental vulnerabilities [1]. Significant social and economic development includes underdeveloped infrastructure, a dynamic and challenging geographical environment, diverse cultural contexts, and limited institutional capacity [2]. In addition, SIDNs are extremely climate-sensitive and are disproportionately affected by adverse climate-related effects [3]. The digitisation of government services may provide opportunities for sustainable human development and for reducing the impact of the digital divide in SIDNs [4] as citizens gain access to government services through electronic platforms, commonly called e-government services [5]. E-government services enhance transparency and access to public information, building citizens’ trust and generating public value through efficient service provision [6]. Additionally, digital services offer a platform for the government to engage with citizens and other stakeholders in real-time interaction, collaboration, and information management and sharing [7,8].

Governments around the world have rapidly adopted innovative digital service platforms to increase efficiency, transparency, and citizen participation [9]. Whilst digital government services hold a significant potential for transforming public service delivery in SIDNs, the processes surrounding their successful implementation and adoption remain under-researched and poorly understood [10]. Given the lack of internal resources and limited access to ICT infrastructure and financing that are specific to SIDNs [8], it is important to investigate digital transformation processes in SIDNs in more depth, particularly how to develop digital government services in partnership with citizens and in alignment with the unique characteristics of the local context.

Over the years, researchers have proposed various frameworks to support value co-creation in digital public services. These include foundational service logic models [11], ICT-based integration approaches [12], collaborative governance models [13], and more recent sustainability-focused frameworks [14]. However, these models and approaches have been developed in the context of developed countries and geopolitical regions and assume the existence of strong governance institutions, advanced infrastructure, and well-established digital ecosystems [2,8].

These assumptions may not be realistic enough for SIDNs, where government systems are often fragmented, resources are limited, and donor dependency is common. This study addresses the gap by exploring practical, context-sensitive ways of supporting value co-creation in e-government services. The study aims to develop an e-government value co-creation model that builds on existing frameworks and responds to the real-world challenges of co-developing inclusive and locally relevant digital services in SIDNs.

1.1. Digital Services in SIDNs

Similarly to digital service programmes in low- and middle-income countries, SIDNs faced challenges such as limited resources and lack of infrastructure, which affect the successful implementation and sustainability of digital services [10,15]. For example, infrastructure constraints such as unreliable Internet connectivity make it challenging to bridge the digital divide [5,10]. The geographical dispersion and the remoteness of many island communities create logistical difficulties in implementing and maintaining consistent digital services [10]. These challenges are exacerbated by SIDNs’ inherent vulnerabilities to natural disasters [16] and require the development of locally adaptive strategies [7].

The diverse cultures, relatively low digital literacy, and the economically and politically unstable environment present additional challenges [17] that limit the adoption and effective utilisation of e-government services by Islamic citizens [18,19]. Furthermore, the e-government ecosystems are often fragmented, and frequently, there is a gap between the design and the delivery mode of digital services and the actual needs of the communities they aim to serve [4]. There is a need for the development of e-government digital platforms that promote inclusivity, participation, and citizen trust [20].

Finally, many SIDNs rely heavily on donor-funded digital projects, which may have inadequate long-term sustainability plans. Donor dependency is a systemic vulnerability: when external support ends, the digital initiatives may collapse or stagnate [15]. Therefore, it is important to build local capacity to ensure the continuity of the digital transformation project [18,21].

The challenges outlined above require realistic, locally grounded and scalable approaches to developing digital platforms and services that consider SIDNs’ social, economic, and environmental characteristics and offer participatory, context-specific solutions rooted in collaboration between governments, communities, and development partners.

1.2. The Shift Towards Value Co-Creation

E-government services have traditionally been developed and implemented through a top-down approach, where governments shape the services and solutions predominantly based on their perspectives. This method may not involve citizen participation in e-government initiatives [22] and leaves little room for citizen and stakeholder input [23]. The limited user engagement may lead to digital services that are not well aligned with citizen needs and inefficient service delivery [21,23].

These shortcomings have driven a shift towards a value co-creation approach that emphasises collaboration and interaction between government institutions, citizens and other stakeholders [24]. Value-adding and adaptive e-government services and innovative user-centred platforms empower service users and customers who are able to contribute actively to the development of impactful and sustainable e-government service [25]; governments benefit from streamlining operations to optimise resource allocation and cut costs and from enhancing transparency and accountability [26]

Value co-creation engages citizens as active partners in designing, implementing, and evaluating digital services rather than as passive users [27]. The participatory approach improves service relevance and responsiveness and legitimises government initiatives by fostering trust and a sense of ownership [28]. However, SIDNs are often challenged to identify the most appropriate and effective way of co-creating digital services [2,5].

1.3. Theoretical Foundation

Prahalad and Ramaswamy [29] defined value co-creation as a joint value creation by the company and its customers; customers actively participate in tailoring services to their needs. The concept of value co-creation aligns with the theoretical framework of service-dominant logic (SDL), which is a service-centred alternative to the more traditional product-dominant. SDL and the co-creation of value are at the core of the service science perspective on complex service systems [30].

In the context of e-government, service systems are designed and shaped through a collaborative environment that supports resource sharing and teamwork processes. Service value is created through collaboration and multi-stakeholder engagement, applying participatory and collaborative methods, and using citizens’ input and expertise [26,31,32]. To develop the theoretical foundation of this study, the sections below review prior research to identify co-value creation processes, influencing factors, and practical methods relevant to value co-creation in e-government services.

1.3.1. Processes Supporting E-Government Service Value Co-Creation

The review of the literature identified several important processes that support value co-creation initiatives in e-governance. The key points are synthesised as follows:

- Organisational facilitation and coordination

The government plays a central role as a facilitator and coordinates the work of the collaborators who contribute their generated ideas, designs, and innovations [5,14]. The aim is to engage public, private, and third-sector organisations in a transparent process of cross-sector collaboration to enhance service comprehensiveness [7] and through teamwork and shared vision and objectives [21,33,34].

Intermediaries such as non-government organisations (NGOs) can bridge the engagement gap between citizens and the government [18], and including citizens in planning and decision-making builds trust and creates a sense of shared power and responsibility [35,36,37]. A supportive governance framework of policies and regulations to ensure that the value co-creation practices are ethical and compliant with legal standards and that the stakeholders interact in a structured and inclusive manner [10,15].

- 2.

- Integrating advanced technologies

Technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics support decision-making, trust-building and personalised service delivery [32]. These tools enable multi-directional communication and secure, transparent information flows that support ongoing collaborative interaction [6,7].

- 3.

- Capacity building and training

Training and capacity-building programmes help educate stakeholders to gain relevant skills, foster engagement, and support long-term participation in service co-creation [21]. These programmes, including international and regional ones, enable the transfer of knowledge to local actors and communities, thus encouraging and sustaining their contributions [10,25].

- 4.

- Feedback and interactive engagement mechanisms

The establishment of a transparent mechanism is necessary for refining service delivery and maintaining user motivation and confidence [5]. The feedback channels should be traceable, responsive, and adaptive to align service outputs with customers’ needs and expectations continuously [32,38,39].

1.3.2. Factors Influencing Collaboration

Effective collaboration is central to successful value co-creation in e-government services. It is influenced positively by enablers such as trust, leadership, and resource management; inhibitors such as technology complexity and access to technology and citizens’ digital literacy and cultural diversity. The key points are synthesised as follows:

- Trust

Trust is a key enabler, shaping public confidence in government digital services, and its security significantly impacts citizens’ willingness to engage [40]. Trust in the government’s intentions and the security of the digital platform will dramatically increase engagement [5]. The lack of trust is often rooted in a poorly managed co-creation process, where citizens sense that their data is not safe, a lack of transparency, and weak accountability, ultimately leading to disengagement and scepticism [32,41]. In developing contexts, trust is often undermined by historical governance failures [42].

- 2.

- Leadership, vision, and policy clarity

Strong government leadership, supported by clear policies and a shared vision, helps create coordinated strategies and simplifies bureaucratic processes, making public services more accessible and practical for citizens [24,38]. Without clear policies, responsibilities become blurred, discouraging engagement and hindering adaptation and innovation [22,43].

- 3.

- Resource sharing and management

In resource-constrained environments, forming collaborative partnerships enables the pooling and sharing of both tangible and intangible resources [10]. The exchange of experiences, knowledge, and insights is a critical form of resource sharing that helps align stakeholder priorities and supports the development of sustainable, context-specific solutions [20,32]. Access to shared resources raises a sense of shared ownership among stakeholders, which in turn builds shared responsibility, encouraging citizen participation in both the design and implementation of services [21,25]. This shared responsibility contributes to a balanced relationship between stakeholder empowerment and formal governance, enhancing long-term value co-creation and innovation [37,39].

- 4.

- Technological barriers and complexities

Complex and poorly integrated e-government systems often discourage citizen engagement, especially among those with limited digital skills [5]. Inadequate infrastructure, such as unreliable internet and platform access, combined with a shortage of technical staff, further limits system usability in developing contexts [10,25].

Beyond infrastructure, low digital literacy also remains a key barrier, particularly for older adults, rural populations, and those with limited education. Social norms may also influence who feels confident using digital services, reinforcing digital exclusion if not addressed [7,38,44].

1.3.3. Value Co-Creation Methods

Value co-creation in e-government is supported through participatory methods such as co-design workshops, agile development, and collaborative prototyping. These methods foster deeper stakeholder engagement in service development [45] as they promote interactive feedback loops, user-driven design, and continuous improvement. The key points are synthesised as follows:

- Participatory design

Participatory design methods involve citizens directly in shaping digital services, helping ensure alignment with user needs while reducing resistance to adoption [27]. One key approach is co-design workshops, which bring together government actors, designers, and citizens to identify solutions and refine service delivery collaboratively [27]. These workshops help address challenges such as the design-reality gap [21], foster innovation grounded in local knowledge and resources [25], and support the development of more usable and relevant digital tools [7,38].

- 2.

- Agile development

Agile development offers a flexible and collaborative way to build digital government services that can adapt as needs change. Instead of following rigid plans, agile methods focus on working in short cycles, gathering feedback early, and making improvements along the way [17,21]. This ongoing process helps ensure that the services are developed, enhanced, and adjusted according to citizens’ feedback and changing needs and expectations [7,20,38].

- 3.

- Collaborative prototyping

Collaborative prototyping facilitates and creates opportunities for real-time interaction, allowing citizens to share input through focus groups, online platforms, and mobile apps [5,38]. For example, the Estonian government used this method to test and improve digital tools in a controlled setting, helping ensure functionality and usability before rollout [21]. In some cases, a transparent feedback system lets participants track their status and take advantage of monetary or motivational incentives for participation [7].

1.4. Research Questions and Contributions

As mentioned earlier, e-government value co-creation processes reviewed above have been investigated and modelled in the context of both developed and emerging economies; however, there has been little research on the impact of the specific SIDN challenges on the effectiveness of e-government value co-creation. These include remoteness, limited digital infrastructure, geographically dispersed populations, and dependence on external aid [10,17]. In particular, the factors influencing e-government value co-creation have been examined in different global settings; however, there is a lack of research on how they are manifested in the SIDN context, which is characterised by limited resources [21,45] and a lack of financial and technical infrastructure support to keep the services running in all circumstances [25].

Moreover, in regions such as scattered and remote islands [10], the geographic isolation, the cultural diversity [7], and the vulnerability to natural disasters lead to the use of a top-down approach [21]. The resulting imbalance of power impedes effective collaboration [15,32]. In addition, the e-government value co-creation methods that have the potential to strengthen collaboration among government, citizens, and other stakeholders and enhance service delivery and quality have also been examined in developed and resource-abundant settings. Their applicability to resource-limited environments, such as SIDNs, remains largely unexplored [5,17,18,28].

To achieve its aim, this study identifies the contextual factors and conditions that influence e-government value co-creation and proposes a value-co-creation framework that adapts established co-creation processes and methods to support sustainable e-government initiatives in resource-constrained island settings. The following research questions guided the study:

- RQ1. What factors can enable or hinder effective collaboration in e-governance services in SIDNs?

- RQ2. What value co-creation processes can support in e-government services in SIDNs?

- RQ3. What methods can support value co-creation in e-government services in SIDNs?

Research questions one and two investigate the factors influencing collaboration and the key processes that facilitate value co-creation. Together, they lead to addressing the third research question: identifying the value co-creation methods that can be adapted to enable e-government service development in SIDNs and to support inclusivity and sustainable digital service delivery.

The study makes the following important contributions. First, it identifies effective cooperative solutions to aid in developing sustainable, user-focused e-government services, overcoming the challenges specific to the SIDN’s context. Second, it provides actionable insights for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers about the methods that can be used to enhance the design and delivery of sustainable, user-centred digital public services in resource-limited and vulnerable environments. Finally, the study contributes a value co-creation framework that is aligned with the realities of SIDNs in which cultural diversity, limited resources, and political instability often hinder the success of imported digital models.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 presents the methods used in participant sampling, data collection, and data coding and analysis. Section 3 and Section 4 explore the findings in detail and discuss their significance and implications in light of the research questions and objectives of this study. The conclusion briefly summarises the paper and its contributions, acknowledges the limitations of the research, and provides directions for further research.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employs a qualitative case study approach to investigate value co-creation processes in e-government services within SIDNs. This section presents and justifies the research approach and describes in detail the methods used to gather and analyse the study data.

2.1. Research Approach

This research is grounded in social constructivism and interpretivism, which posit that knowledge is constructed and interpreted through social constructs and contextual influences, seeking to understand individuals’ unique viewpoints [46]. To achieve its objective, this study applied a qualitative case study approach. As pointed out in [47,48], this approach is suitable for the exploration of complex and evolving phenomena such as value co-creation in SIDN e-government services. It allows for an in-depth exploration of stakeholders’ experiences, interactions, and perceptions, alongside the organisational and social processes [49,50]. Since value co-creation in e-government services is dynamic and context-sensitive, a qualitative case study approach is well-suited to facilitate a comprehensive investigation of the factors influencing stakeholder collaboration and service outcomes [51,52]. Moreover, the use of a qualitative case study ensures a rigorous and trustworthy analysis of participant contributions to e-government service development [53].

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, inviting participants to share their experiences of the current e-government services; this allowed for capturing subjective responses that were relevant to the core research objectives [51]. The data were analysed using thematic analysis [54], identifying key patterns and themes that contribute to the understanding of value co-creation processes in e-government services.

The case study was conducted in a government department in Vanuatu. This department was selected because it provides e-government services, and its staff possesses a strong understanding of the factors and processes involved in value co-creation. Specifically, this department delivers comprehensive ICT projects and utilises technology and digital tools to gather data and offer digital service products to citizens and stakeholders.

2.2. Participant Sample

The study’s target population consists of stakeholders of e-government services, especially those directly involved in the collaboration, design, development, delivery, and use of the e-government service. The target population includes department managers, policymakers, technical staff, and personnel who are engaged daily with e-services products for citizens and customers. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants. This ensures that participants have direct experience with e-government services, are active members and have some knowledge about e-government services [49]. The procedure involved first seeking permission to undertake research in the selected department.

Potential participants were invited to participate via email. Respondents were screened to ensure they held significant experience with e-government services, occupying roles such as policymaker, manager, technical specialist, or citizen-facing stakeholder liaison. Fifteen respondents were selected as potential participants. Data saturation was reached by the tenth interview, with no new substantial themes emerging. This is consistent with similar digital service co-creation studies that examine the types of resources and interactions influencing co-creation value outcomes in developing contexts [55]. It also aligns with qualitative research methodology, where thematic saturation is often reached within six to twelve interviews when participants share similar roles or experiences [56]. Of the ten participants, three had managerial and policy-making backgrounds, three held technical roles, and four engaged regularly with citizens and external stakeholders regarding the department’s digital services.

2.3. Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were employed as the data collection method due to their flexibility and ability to deeply explore participants’ experiences in a consistent manner. while highlighting emergent themes related to the research questions [57]. Following Kasllio et al.’s framework for developing interview questions in qualitative research [58], the interview guide operationalised the knowledge gained from the literature review on the value co-creation process, factors and methods (refer to Section 1.3).

A questionnaire comprising 30 questions (Appendix A, Table A1) was developed and used as the data collection research instrument. The interview questionnaire aimed to elicit responses that contributed new knowledge and insights related to the objectives of this research; therefore, aligning the interview guide with the research questions enables a meaningful and in-depth exploration of participant views, opinions and experiences [59]. Subsequently, the interview questions were grouped into focus areas representing different aspects of the study. Interview questions IQ1–IQ3 probed participants’ background, while interview questions IQ4–IQ7 explored views on current e-government services, aligning with RQ1 and RQ2. Questions IQ8–IQ11 focused on collaboration and stakeholder roles (RQ1 and RQ2), and IQ12–IQ20 examined the role of technology and data along with their governance, sustainability, and integration in co-creating value (addressing RQ3). Interview questions IQ21–IQ25 elicited views and opinions on citizen engagement (RQ2), and IQ26–IQ27 explored challenges affecting value co-creation (RQ1 and RQ3). Finally, IQ28–Q30 invited participants to reflect on the topic of the study, cutting across all three research questions. The third column of Table A1 shows the tentative mapping between interview questions and research questions.

An ethics clearance was obtained from the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee (AUTEC). Participants who agreed to participate were asked to sign the consent form. The average length of the interviews was 45 min. Interviews were audio recorded; one of the authors took notes throughout the interview process.

All participants used a blend of English and Bislama, the national language of Vanuatu, during the interviews. The online platform TurboScribe [60] was used to transcribe each recording. As a multilingual translator, Turbo Scribe translated interviews that were a mixture of English and Bislama into English. All transcripts were reread while listening to the audio file to ensure that the transcribed data accurately reflected what the participants were stating.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data analysis process included two main stages: data coding and thematic analysis. The qualitative data collected from stakeholder interviews (amounting to a total of 35,000 words) were first coded using an open coding approach to identify patterns and recurring ideas. These initial codes were then organised into super codes and examined through thematic analysis to uncover super themes and derive insights aligned with the research questions.

2.4.1. Data Coding

The cleaned transcribed interview data were re-imported into NVivo. Applying an open coding approach [61], each interview transcript was repeatedly read to understand the content and to search for emerging patterns. The data segments associated with each pattern were interpreted to derive meaningful codes. A total of 201 codes were initially developed and defined. Table 1 presents an example of a code and its definition.

Table 1.

An example of a code.

Next, we revisited the codes and their descriptions to identify codes that were related to the same broader concept. The resulting groups of related codes were conceptualised as a second coding level of ‘super codes’. Each super code inherited the descriptions and the data segments associated with its underlying first-level codes. This approach allowed the representation of the interview data in a more structured yet meaningful way.

An example of a super code is provided in Table 2. The codes Integrated Data Platform, Inter-department Data Integration, and Interdependent Systems Design capture particular views about the need for a system that integrates data within and between departments. For instance, under the code Inter-department Data Integration a participant states, “Develop a system in such a way that they support each other and run side by side” (DeptBInt3, 27:59–30:58). The three codes were grouped together as a super code, ‘Data and Systems Integration’, which emphasises the importance of developing integrated and interdependent systems. Following this approach, a total of 57 super codes were similarly identified.

Table 2.

An example of a super code.

2.4.2. Thematic Analysis

Further analysis and examination of patterns within super codes revealed emerging themes, one of which is technology-enabled services (Table 3). As shown, the theme emerged from super codes related to data and system integration, focusing on how digital platforms can be used for dissemination and customised to meet the specific needs of citizens. Therefore, technology-enabled services align well with this concept.

Table 3.

An example of a theme.

As defined in Table 3, the theme “Technology-Enabled Services” presents a pathway for digital solutions that enhance efficiency, accessibility, and effective service delivery. The underlying super codes highlight the importance of integrating data and systems with tailored technology solutions. This approach enables e-government services to operate efficiently, even when resources are limited, ensuring that user expectations are met. A similar approach was used to analyse the rest of the super codes, ensuring a logical progression from raw data to overarching themes and providing a deeper understanding of e-government value co-creation in the context of the case study. A total of 15 themes were identified and defined.

The next step involved reviewing and interpreting the data associated with each theme to identify relationships across themes. Related themes were grouped together to form a super theme. Each super theme inherited the super codes and the supporting data excerpts associated with the underlying themes.

In the example shown in Table 4, the super theme Digital Transformation and Data-Driven Governance emerged from the group of related themes Data Governance, Digital and Data-driven Decision-making Tools, and Technology-enabled Services. Together, these e themes encompass the relationship between data governance, digital tools to support data governance, and government systems for data analysis and decision-making. The overarching super theme of Digital Transformation and Data-driven Governance encapsulates the provision of efficient service delivery. Following a similar approach, another four super themes were identified and defined: Citizen Engagement and Collaborative Communication in E-government, Strategic Governance, Collaboration and Communication for Multi-Stakeholder Engagement, E-government Resilience and Technology Infrastructure Readiness, and Sustaining E-Government through Strategic Partnerships for Resource, Capacity Building, and Workforce Optimisation.

Table 4.

From super codes to themes and super themes: An example of an emerging super theme.

3. Research Findings

The findings of this empirical study reveal the essential aspects of value co-creation in e-government services for SIDNs. They show that citizen engagement, strategic governance, collaborative communication and partnership, and technology integration are enablers of effective value co-creation in e-government services, as supported by the further analysis of the five super themes defined through interview data coding and analysis (as described in Section 2). This section presents and discusses the findings of this research concerning factors influencing and processes involved in value co-creation.

3.1. Super Theme 1: Citizen Engagement and Collaborative Communication in E-Government

This super theme comprises three themes: citizen awareness and involvement, citizen engagement and feedback mechanisms, and communication and collaboration. These themes are key to understanding the drivers of citizen engagement and collaboration.

Citizens’ engagement is vital for shaping e-government services. However, despite efforts to involve citizens, barriers remain, including the lack of awareness and insufficient participation. The absence of proper engagement and feedback mechanisms has hindered stakeholder collaborative communication.

3.1.1. Citizen Awareness and Involvement

The lack of proper awareness and limited public participation impact the understanding and learning curve of e-service products that require scientific knowledge and interpretation. One participant stressed that the lack of public understanding of the service product is of significant concern, stating, “Many of our products and information are not fully understood by the citizens” (DeptBInt8, 26:08–29:47). Farmers, for instance, are not aware of the scientific data and technical details that influence their decisions for planting. This lack of awareness is convincing evidence that climate change will affect the planting period and, consequently, the suitability of crops, presenting a significant issue. “This information is new to citizens […] they do not know what weather and climate mean, and they do not realise they can plant using the relevant information” (DeptBInt4, 4:58–6:03).

In addition to this, interpreting symbols is still a challenging task since simplification often compromises the meaning. Thus, a participant pointed out that “The symbols are not clear to the common people on the street […] most of them are not able to even identify some of the symbols we use.” (DeptBInt1, 13:19–16:46). The public’s engagement has shown to be one of the key drivers of quality by applying co-creation through information personalisation and tailoring to meet their needs, as one participant stated, “Many citizens request the way we do our information and what they want to get from it” (DeptBInt8, 38:02–39:12).

3.1.2. Citizen Engagement and Feedback Mechanisms

Citizen engagement is vital in making e-government services use-ready and aligned with users’ expectations; however, factors such as barriers to engagement, feedback limitations, and communication gaps hinder citizen engagement. Several reasons make it difficult to capture public input and feedback. Most of this happens as a result of the available technical infrastructure and resources, as well as locations, which ends up preventing a considerable portion of the population from being reached, as one participant stated, “We cannot provide the information to everyone […] when we use Facebook, we only reach Facebook communities, and SMS only reaches a few areas with network coverage” (DeptBInt6, 16:40–20:39).

Citizens’ feedback mechanisms include a variety of approaches or are used in combination, such as call-in services, surveys, public forum spaces, and social media that improve service responsiveness and bridge communication gaps. One participant had this to say, “There is a voice-free toll number where people call in […] we analyse the request from people who give their opinion whenever they call in using that number” (DeptBInt1, 29:53–32:49). “Forums that we have like national climate outlook forums […] is a space where people can voice their needs to stakeholders, especially what they want” (DeptBInt1, 46:47–51:45). Through social media feedback, users expressed appreciation for timely updates, as noted in “Constructive feedback we get from especially social media […] most of them are appreciative that we put this information out timely” (DeptBInt1, 44:43–45:51).

3.1.3. Communication and Collaboration

Effective collaboration strategies and communication are crucial for engaging various stakeholders. However, some obstacles impede this engagement process. Key issues include the main point of contact challenges, inadequate knowledge sharing, and a lack of alignment in collaboration. Participants noted, “There are some challenges regarding communication, contact and focal points.” (DeptBInt4, 19:57–20:07), “Our understanding must be in line them and only then will it work.” (DeptBInt3, 37:35–39:58), and “The collaboration between the five sectors […] is not that good… all the officers allocated to work with us already have a full load of work.” (DeptBInt8, 45:25–47:08). Inter-agency collaboration is vital for facilitating knowledge exchange and enhancing governance strategies. One participant remarked, “The officers, too, must have the initiative to come work together with other entities, listen, and collaborate with other experts” (DeptBInt10, 29:25–50:48).

A significant finding emphasises the importance of integrating traditional knowledge with scientific data, as this can enhance service accessibility and provide value to citizens. One participant asked, “How do we best integrate traditional knowledge with scientific ones?” (DeptBInt10, 29:25–50:48).

Communication challenges persist, particularly with focal point contacts, causing delays in information dissemination that can impact emergency responses. As highlighted in one participant’s statement, “If I want to send a tsunami message […] by the time we would have lost 5 to 10 min, so that is another hurdle” (DeptBInt1, 25:15–26:02). Additionally, delays in communication and information sharing during natural disasters like cyclones and earthquakes have resulted in social backlash and negative feedback regarding services. One participant noted, “When we do not provide timely messages, we get all sorts of negative comments on social media because of not reaching them on time” (DeptBInt1, 26:09–27:00).

3.1.4. Summary of Super Theme 1

The findings suggest that citizen engagement may be fundamental to the success of e-government services. Yet, it appears to remain hindered by limited public awareness, unclear communication formats, and barriers to participation in service design and feedback. Despite the availability of platforms such as SMS, toll-free call-ins, and social media, challenges related to infrastructure, digital literacy, and outreach seem to continue to restrict inclusive engagement and responsive service delivery. Additionally, weaker communication between agencies, disjointed collaboration, and delays in sharing vital information, particularly during emergencies, highlight the possible pressing need for unified communication strategies and cooperative methods that prioritise citizen feedback and traditional knowledge in the development and accessibility of services.

3.2. Super Theme 2: Strategic Governance, Collaboration, and Communication for Multi-Stakeholder Engagement

Governance is essential in facilitating stakeholder collaboration and communication to strengthen their engagement. Three themes—governance challenges, obstructions to coordination and communication, and decision-making complexities—impact stakeholders’ engagement.

3.2.1. Governance Challenges and Stakeholder Engagement

The findings reveal that governance challenges, accountability issues, and gaps in stakeholder engagement significantly impact multi-stakeholder collaboration. Political influences and differing perspectives can cause executive disconnection and a lack of administrative vision, leading to a misalignment of leadership vision. Participants stated, “I think politics must have influenced them. They have reached a level that interfaces with politics, so they deal with politicians. That is why when they go up there, they become different and end up being the same as those who came before them.” (DeptBInt6, 29:07–33:43). “In the government, people at the executive level have a different perspective depending on the level of jobs that they are in […] However, when they do not see what we see, they ignore it” [DeptBInt3] (44:00–45:55) resulted in a disconnection, as one participant stated, “Being expert of that area, you know what you are talking about, but if they see it differently, like if you talk about orange and they see it as apple, it is not going to work” [DeptBInt3] (14:45–15:41).

The absence of trust in local expertise undermines decision-making and innovation, as one participant noted, “A lot of our superiors, especially the directors, don’t trust officers even though we are in positions that require expert knowledge” (DeptBInt6, 23:55–28:51). Additionally, political instability and leadership turnover created uncertainties, disrupting long-term planning and governance continuity, as highlighted in the statement, “Vanuatu is on the top of instability in politics” (DeptBInt4, 42:31–42:56). Systemic barriers in leadership and executive misalignment further hinder institutional progress, with a participant stating, “The challenge now is our argument with the administration… the problem is they don’t see that vision” (DeptBInt1, 39:47–43:26). Enhancing stakeholder engagement is vital for boosting governance effectiveness, as shown by sector liaison coordination efforts, where one participant emphasised that, “Sector coordinators act as climate liaisons between departments” (DeptBInt4, 25:56–27:22).

3.2.2. Collaborative Resource Sharing and Communication Strategies

The findings highlighted effective communication strategies, collaborative resources and training as critical roles in enhancing multistakeholder governance. The collaborative strategy emphasises training, community outreach, and establishing an effective communication structure. This will enable cross-sector partnership, knowledge integration and strategic alignment to support effective collaborative governance and service delivery.

Collaboration levels and their dynamics among stakeholders are necessary to co-create value, as stated, “In all development levels, […] there must be upward or downward collaboration. Both ways must happen.” (DeptBInt3, 46:08–48:11). With suitable collaboration strategies implemented, training needs are identified, and costs and data can then be shared and modelled collectively. Participants stated, “We have many collaborations as well with scientific projects and the scientific community […] Experts that run the training.” (DeptBInt5, 25:46–29:31), “We did crop modelling in demonstration plots and collected data every day.” (DeptBInt4, 8:06–9:57), “To share the load, a department looks at the operational cost while we look at the data and share it with you.” (DeptBInt9, 18:55–23:30).

Collaborative training and data modelling enhance the system improvements, as noted in “We have many collaborations with scientific projects and the scientific community… Experts that run the training” (DeptBInt5, 25:46–29:31).

Community outreach programs ensure that vital services reach the populations of very remote areas, with one participant stating, “We aimed to reach people to the last mile, reach everyone with what we were producing for them to be updated and prepared” (DeptBInt2, 9:05–10:16). However, internal communication challenges such as delays and consultation gaps hinder collaboration, as highlighted in “If I want to send a tsunami message… by the time we would have lost 5 to 10 min, so that is another hurdle” (DeptBInt1, 25:15–26:02).

Additionally, public outreach communication channels such as radio agreements and social media platforms are used to improve information dissemination, with one participant explaining, “The Facebook page is called Vanuatu Climate and Ocean Services. We use this platform to push out information to the citizens” (DeptBInt8, 7:58–10:36).

3.2.3. Decision-Making in Collaborative Governance

Effective decision-making in collaborative governance relies on partnerships across different sectors, the integration of knowledge, and collaboration tailored to specific sectors to promote evidence-based policies and service delivery. Cross-sector collaboration encourages the exchange of knowledge and resources, as illustrated by a participant who mentioned, “We developed the ocean product together with the fisheries department” (DeptBInt8, 40:14–41:10).

Additionally, while the integration of traditional and scientific knowledge shows excellent potential, it remains a work in progress, with one participant asking, “How do we best integrate traditional knowledge with scientific ones?” (DeptBInt10, 29:25–50:48). Collaboration specific to each sector further enhances governance strategies by ensuring that specialised expertise informs decision-making. One participant highlighted this by saying, “They have built collaboration with other departments like agriculture […] to help people, give them the idea of the best state of planting” (DeptBInt2, 20:44–23:09).

Moreover, regional scientific collaboration fosters the integration and sharing of data across regions, as noted by a participant, “We have the scientific collaboration of scientific communities including regional, Australia and New Zealand. The advantage is it allows us to share data and allow data to flow between countries.” (DeptBInt5, 25:46–29:31). Telecommunication partnerships are also vital for decision-making and emergency response, with one participant stating, “We have an agreement […] during tropical cyclone […] for warnings messages, we switch that free toll number so people can call and talk to someone directly” (DeptBInt2, 52:47–54:20). However, challenges remain due to governance misalignment and a lack of strategic clarity, as highlighted in the observation, “The driving factors rest solely in the hands of policymakers” (DeptBInt3, 37:35–39:58).

3.2.4. Summary of Super Theme 2

The findings indicate that effective value co-creation in e-government services within SIDNs may depend heavily on addressing strategic governance challenges, such as leadership instability, weak accountability structures, and limited stakeholder participation. Successful initiatives appear to thrive on citizen engagement, collaborative communication strategies, and partnerships among multiple stakeholders. These may be enhanced by organised communication frameworks, resource-sharing mechanisms, and multilingual dissemination methods that extend to the most remote communities. Furthermore, integrating appropriate digital tools and cross-sector data platforms may help enhance decision-making, align public–private collaboration with long-term governance strategies, and ensure the sustainability and inclusiveness of digital service delivery.

3.3. Super Theme 3: Digital Transformation and Data-Driven Governance

Data and cutting-edge technology are crucial for successful governance in today’s fast-changing digital environment. E-government performance and enhancement are realised through tailored, technology-enabled services and digital tools that support informed decision-making. The themes of data governance, digital tools and data-driven decision-making, and technology-enabled services exemplify the key drivers of the evolution.

3.3.1. Data Governance

The results show that data sharing, accuracy, and integration difficulties are the significant factors affecting digital governance. Data sharing reluctance is prompted by trust and previous negative experiences, as one participant explained, “They are reluctant to share government properties like data with others because of a negative experience they previously had” (DeptBInt4, 21:22–22:15). Furthermore, data transmission failures such as satellite connection failures affect the flow of information and hamper value propagation, as one participant pointed out that, “We have transmission issues as well; the satellite is down or some other issues that affect the transmission of data” (DeptBInt4, 14:11–15:00).

The finding also reveals that data accuracy is a problem, especially when the primary data sources are not accurate. They must rely on secondary sources, which are not very accurate and consistent, as one participant stressed, “We depend more on the primary data, but if the station is down, then we use the online, but the accuracy does vary depending on the model in use.” (DeptBInt5, 05:55–07:21). The lack of climate-specific data, such as climate fishing data and historical records, hampers accurate forecasting, as indicated by “We wanted data […] climate-related in nature […] that data we cannot find” (DeptBInt4, 23:22–24:29).

3.3.2. Digital Tools and Data-Driven Decision Making

The significance of digital tools in improving decision-making is seen through the collection and analysis of real-time data and the optimisation of system performance. The necessity of real-time data collection is evident, as one participant mentioned, “We have a network of weather instruments around the country that send minute-to-hourly data that we receive in real-time” (DeptBInt1, 03:20–06:49). This real-time data analysis offers practical benefits to citizens, such as for fishermen, “We provided information indicating that during this period, the amount of chlorophyll will be in these areas, and you can find this type of fish there.” (DeptBInt8, 36:08–37:36).

Effective data management is crucial, especially ensuring the collected data is stored, analysed, and shared appropriately. ICT teams are vital in this process, as noted in the statement, “We at ICT look after the data coming into the data centre” (DeptBInt9, 08:10–10:24). Furthermore, automation plays a key role in enhancing efficiency, with participants advocating for more streamlined dissemination processes, such as using pre-prepared templates for emergency alerts, “We just fill in one or two details and send it to people. Currently, it is slow” (DeptBInt6, 35:42–37:56). Thus, emphasise the necessity for strong data analysis tools, real-time monitoring, and automation to support digital transformation and governance.

3.3.3. Technology-Enabled Services

Technology does play a vital role in data integration, accessibility, and service delivery. The findings show that integrated data platforms lead to more efficient operations. One participant shared, “Meteo factory is an integrated system […] inside Meteo factory, we design templates […] and it pushes out to all our clients” (DeptBInt1, 10:03–12:15). Interdepartmental data integration is also important for effective collaboration, as noted by one participant: “The technician manages the geo-hazard instruments […] telecommunication aspects we request ICT to do it” (DeptBInt9, 00:36–05:50).

Furthermore, utilising social media and informal platforms boosts public engagement and information sharing. A participant emphasised the importance of these platforms, saying, “Facebook is not an official platform, but it is the main one we use for sharing information” (DeptBInt6, 7:08–9:25). Additionally, customised technology solutions are crucial to address user-specific needs, as illustrated by the example, “For instance, a pilot would not need what a commoner would want […] they need wind shear data at the airport” (DeptBInt1, 07:27–8:03).

3.3.4. Summary of Super Theme 3

The findings suggest that digital transformation is likely a critical enabler of value co-creation in e-government services, driven by the integration of real-time data sharing, tailored technology solutions, and digital platforms that support informed governance and user responsiveness. Enhancing decision-making in governance may require the use of robust data analysis tools, improved verification mechanisms, real-time monitoring, and automation to streamline workflows and improve service efficiency. Furthermore, these results appear to emphasise the importance of integrated data platforms, cross-sector digital networks, and inclusive communication channels, such as social media, to potentially enhance citizen engagement, reinforce collaborative governance, and ensure sustainable, data-driven public service delivery in small island developing nations.

3.4. Super Theme 4: E-Government Resilience and Technology Readiness

Integrating technologies and working together to empower stakeholders and disseminate information, with capacity training, will help tackle issues of outdated systems, network coverage and resource limitations. To provide continuity of e-services, mainly when technology is evolving and natural disasters are increasing, this section discusses three key themes to enable e-government to be resilient and ready, adapting and optimising the use of technological infrastructure. These themes are technological and infrastructure barriers, empowerment and capacity building for resilience, and technological integration for preparedness.

3.4.1. Technological and Infrastructure Barriers

Vandalised systems, infrastructural failures, and gaps in technical capabilities greatly hinder the effectiveness of e-government services. Inaccurate systems and insufficient maintenance resources create further inefficiencies. As one of the participants stated, “Some of the problems that we faced were the vandalism on the stations. The stations are cut and broken, even requiring steel parts” (DeptBInt5, 05:55–07:21).

Furthermore, as noted by one participant, “We are using an old version of the software that offers minimum features,” which cumulatively with neglected maintenance inflates the inefficiencies (DeptBInt1, 17:00–18:34). As noted by a few participants, “Not everyone has access to telecommunications, and in certain areas, the service is not provided. …it is not possible to reach” (DeptBInt2, 10:57–11:33). A significant portion of the regions is lacking IT engineering resources, reducing overall technical skills, thus slowing system maintenance and upgrades. “We lack IT human resources developers… they take time to develop it, or they say they will try but cannot finish it” (DeptBInt3, 23:53–26:03), one participant emphasised. Blocking these loopholes is essential for the empowerment of e-government infrastructures and systems, as well as the building of infrastructures and the development of modernised systems.

3.4.2. Empowerment and Capacity Building for Resilience

The result highlights the roles of training, access to information, and multi-organisational collaboration in building resilience. Community training enhances the capacity of people within the area to operate and sustain essential systems, as one participant explained, “In every station […] there is a station keeper and, so, each station, […] is in a community” (DeptBInt5, 14:38–16:04). In addition, empowering and building trust in graduates improves their innovativeness and responsiveness towards government institutions, with one participant saying, “Young graduates have a different confidence level; they are open and seem to have more confidence” (DeptBInt4, 30:56–33:03).

Facilitation of citizens’ preparedness through readily available climate and weather information is critical in disaster resiliency planning, as highlighted, “In that way it will help people to get prepared […] to save their lives, their property, and the people that they are serving” (DeptBInt2, 9:05–10:16). In addition, cross-sector collaboration is needed to respond to this need, as explained, “We will have sector coordinators that will act as climate liaison officers between the department” (DeptBInt4, 25:56–27:22). These has stressed the importance of community-driven level training, better information distribution, and inter-organisational collaboration to improve the resilience in e-government services.

3.4.3. Technological Integration for Preparedness

Dynamic coping mechanisms are required to utilise real-time data, forecasting, and technology to enable e-government strategies to manage disasters. As one participant pointed out, real-time data capture aids in service delivery. “We have a network of equipment or instruments, they are weather instruments around the country, that send minute to hour data that we receive in real-time” (DeptBInt1, 03:20–06:49). Additionally, one of the innovations is using ashes as data for preparedness measures, “We need to collect ash and derive many products from it.” (DeptBInt6, 23:55–28:51). Their innovation fosters prompt decision-making at critical moments. “[…] daily updates they want to know […] we do two times a day 5 a.m. and 5 p.m. […] three hours hourly updates during a cyclone.” (DeptBInt1, 29:53–32:49).

Collaborations with agriculture and other sectors enhance preparedness and make seasonal forecasting on their behalf feasible. Seasonal forecasting is provided to farmers regarding the appropriate time for planting and harvesting. “The application is capturing the seasonal forecasting for people to get the information […] to help people, give them the idea of the best state of planting” (DeptBInt2, 20:44–23:09). Real-time data integration, cross-sector collaboration, and innovative solutions will contribute to enhancing technological preparedness in e-government services.

3.4.4. Summary of Super Theme 4

The findings appear to emphasise that building resilience in e-government services may require addressing foundational infrastructure gaps, including outdated systems, poor network coverage, and insufficient technical support, particularly in disaster-prone and resource-constrained environments. Strengthening resilience is likely to rely on the integration of technology, such as real-time data systems and forecasting tools, which can empower stakeholders through community-level training, inclusive information dissemination, and multi-agency coordination. These approaches highlight the importance of preparing institutions and citizens to sustain service delivery, adapt during crises, and support long-term system continuity through collaborative planning and digital readiness.

3.5. Super Theme 5: Sustaining E-Government Through Strategic Partnerships for Resource, Capacity Building, and Workforce Optimisation

Sustainability in e-government services hinges on forming strategic partnerships that enhance resource sharing, foster capacity building, and strengthen the workforce. By collaborating with government agencies, civil society, and the private sector, resources can be utilised more effectively to improve digital services (themes strategic partnerships and multi-stakeholder collaboration, collaborative resource and financial optimisation, and capacity building and workforce optimisation).

3.5.1. Strategic Partnerships and Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

Collaboration among government agencies, private sector partners, and regional stakeholders is crucial for maintaining e-government services. Working together in decision-making enhances governance structures, as one participant mentioned, “Every manager, we are a team to make decisions, everyone should work together” (DeptBInt7, 40:01:42:24). Partnerships across sectors improve service reach and efficiency, demonstrated by the participant stating, “We have that collaboration with telecommunication services… so they could put emergency messages as SMS text through the phones” (DeptBInt2, 20:44–23:09).

Furthermore, utilising resources collaboratively promotes knowledge sharing and capacity-building, with one participant stating, “We have a lot of collaborations as well with scientific projects and the scientific community… Experts that run the training” (DeptBInt5, 25:46–29:31). Initiatives that share resources, like joint data collection and modelling, also enhance decision-making processes, as noted in, “We did crop modelling in demonstration plots and collected data every day” (DeptBInt4, 8:06–9:57). These insights highlight the significance of multi-stakeholder collaboration, shared resources, and integrated decision-making in fostering sustainable e-government development.

3.5.2. Collaborative Resource and Financial Optimisation

Financial limitations and restricted resource distribution pose significant challenges to the upkeep and growth of e-government services. Budgetary limitations hinder system maintenance and operational capabilities, as illustrated by the statement, “The budget is small to run those very expensive scientific equipment’s” (DeptBInt4, 46:56–51:24). Furthermore, reliance on external funding impacts the sustainability of projects, with one participant mentioning, “We kind of depend on finance or projects to help us in how we could address some of the plans that we have and the ideas that we have” (DeptBInt2, 37:37–39:21).

Collaborative maintenance agreements could provide a viable solution for preserving digital infrastructure, as indicated by one participant, “I think we will have a contract that will connect us with them to maintain that service” (DeptBInt2, 35:41–35:55). Yet, challenges in resource allocation and overwhelmed staff affect efficiency, as one participant noted, “We found out that all the officers that are allocated to work with us already have a full load of work” (DeptBInt8, 45:25–47:08). These insights highlight the necessity for sustainable funding models, cost-sharing strategies, and enhanced resource distribution to ensure the durability of e-government initiatives.

3.5.3. Capacity Building and Workforce Optimisation

The findings emphasise the importance of skill development, workforce limitations, and organisational constraints as significant challenges in maintaining e-government services. Gaps in capacity and capability impede technological progress, with one participant expressing, “We want, like, a technology where we advance, but we do not have capacity or capability to advance” (DeptBInt7, 34:29–34:39). Furthermore, workforce shortages and skill gaps restrict service expansion, as noted in the statement, “We plan to expand the observation to marine, but we need more human capacity” (DeptBInt7, 33:22–33:50).

Organisational capacity issues, such as insufficient IT development resources and overwhelmed collaborators, worsen these challenges. One participant pointed out, “We lack IT human resource developers […] they take time to develop it or will try but cannot finish it” (DeptBInt3, 23:53–26:03), while another remarked, “We found out that all the officers that are allocated to work with us already have a full load of work” (DeptBInt8, 45:25–47:08). Additionally, workforce challenges like educational disparities and staff motivation problems affect overall service delivery. One participant highlighted, “The level of education in each division… forecast division is the only one with bachelor’s degree officers” (DeptBInt10, 12:06–12:07), showcasing the skills gap among teams. Another participant pointed out motivation issues, stating, “It is not happening anytime soon, and it is affecting them […] we are trying to find ways to continue to keep them motivated” (DeptBInt1, 54:43–57:26). Training and knowledge development are essential for addressing these obstacles, with participants stressing the need for exposure and confidence-building, stating, “Exposure helps build confidence… compared to this kind of institution where it deals with outside institutions or organisations” (DeptBInt4, 30:56–33:03).

Additionally, reforms in salary and human resources are essential for attracting and keeping skilled personnel. One participant pointed out that, “Human resources need to change the salary scale […] When you increase the salary, you would also change the job description to reflect the scale and include some benefits” (DeptBInt4, 46:56–51:24). These show the pressing need for focused training, workforce development, and organisational changes to guarantee the long-term sustainability of e-government services.

3.5.4. Summary of Super Theme 5

The findings indicate that the long-term sustainability of e-government services in small island developing nations may depend on strategic partnerships that facilitate resource sharing, collaborative planning, and institutional resilience. Multi-stakeholder collaboration across government, the private sector, and civil society appears to enhance service reach, support shared data infrastructure, and improve decision-making capacity. However, persistent challenges such as limited financial resources, workforce shortages, and organisational constraints highlight the need to improve funding mechanisms, target training, and implement reforms in human resource policies to strengthen institutional capacity, retain skilled staff, and optimise service delivery through coordinated governance and cross-sector support.

4. Discussion

Addressing RQ1, the findings of the study confirmed the relevance of several known factors influencing collaboration: leadership clarity, inter-departmental coordination challenges, and digital literacy gaps. The findings revealed the SIDN-specific contextual factors: trust-building through traditional authority structures, adaptive leadership under political instability, executive misalignment, distrust in local technical expertise, staff burnout following donor projects, policy limitations on employment and pay, and reluctance to share data due to past negative experiences.

With respect to RQ2, the study confirmed the relevance and need for established co-creation processes such as community feedback loops, digital tool utilisation, and cross-sector collaboration. Additionally, several context-specific processes were identified: the integration of locally sourced environmental data, citizen participation in service demonstrations and awareness activities, timed service updates, youth-driven innovation, local station management, citizen-led service refinement, and informal coordination mechanisms, reflecting grounded and adaptive practice for SIDNs.

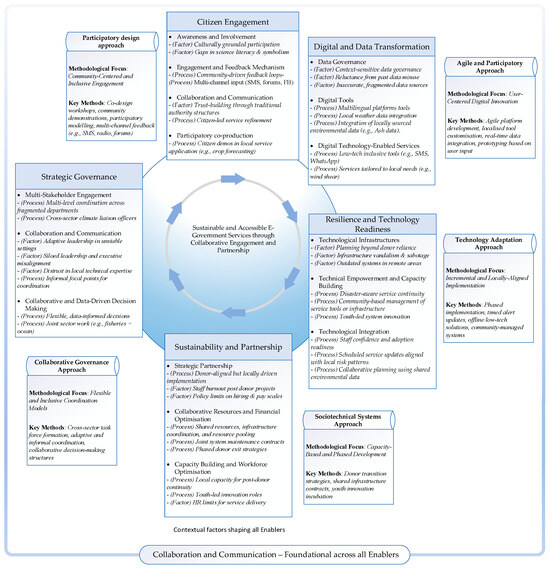

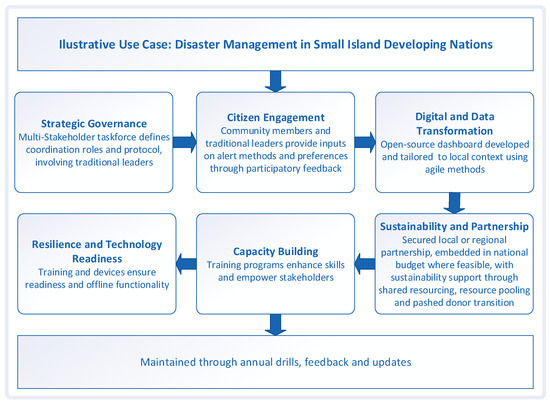

The value co-creation framework that supports collaborative, citizen-centred e-government development within SIDNs (Figure 1) was developed to address RQ3. The framework is built on both the methods identified in the literature review and on the findings of the study; it incorporates five core enablers of value co-creation. Each enabler recognises the role of contextual factors specific to SIDNs and is supported by practical approaches and methods, operationalised through key methods. Collaboration and communication processes incorporate community-managed systems rooted in traditional structures to ensure adaptive coordination aligned with local political and economic risk patterns.

Figure 1.

Multi-methodological framework for value co-creation in E-government services.

4.1. Citizen Engagement and the Participatory Design Approach

Overall, the insights from the interviews highlight that citizen engagement in e-government needs to align with local cultural realities. Participants emphasised the value of involving traditional leaders and village chiefs—what they described as culturally grounded participation—to build awareness and trust. Feedback was often shared through informal community networks like families and churches, reinforcing the importance of community-driven feedback loops. Trust, they noted, grew when respected authority figures endorsed new systems. These findings reinforce the need to design engagement strategies that genuinely reflect the social and cultural fabric of SIDNs.

Starting with engaging citizens, citizens’ awareness, communication strategies, and engagement mechanisms are considered critical to co-creating value in e-government services. One participant stated that the lack of citizen awareness and digital literacy emerged as significant barriers, “Many of our products and information are not fully understood by citizens” (DeptBInt8, 26:08–29:47). This suggested that when citizens are not made aware of the e-services, it is doubtful that they will get themselves involved. Precise and timely information increases trust and citizen engagement [38].

According to Capolupo, Piscopo and Annarumma [32], the trust mechanism allows citizens to engage in the design and enhancement of e-government services actively. They use participatory design, where citizens actively design and co-create solutions. As such, the solutions created will meet and reflect the needs of the citizens. Moreover, fragmented feedback mechanisms affect citizens’ participation. One participant emphasised, “We cannot provide the information to everyone… When we use Facebook, we only reach Facebook communities, and SMS only reaches a few areas” (DeptBInt6, 16:40–20:39). Open innovation, participatory methods, and feedback mechanisms are essential to foster engagement and collaboration in the design and delivery of a service. Studies on participatory design highlight that successful co-creation requires multiple engagement channels, inclusive design, and iterative feedback loops [21]. The discussion suggests that a participatory design approach is required for successful value co-creation. This will ensure citizens are co-designers of e-government services, establish inclusive engagement using multiple engagement platforms, and empower citizens with the necessary skills.

4.2. Strategic Governance and the Collaborative Governance Approach

Overall, the interview findings highlighted the need for multi-level coordination across fragmented departments, as many agencies operated in silos. Leadership changes and unclear mandates also pointed to the importance of adaptive leadership in politically unstable settings. Finally, while data use was seen as critical, participants stressed the need for data-informed yet flexible decision-making to adapt to shifting local dynamics. These insights emphasise the need for governance strategies that are both coordinated and responsive to SIDN contexts.

Governance plays a significant role in value co-creation coordination efforts. For proper governance, the findings show a need for multistakeholder engagement, enhancing collaboration and communication to ensure realistic and current data drives decision-making. This reflects the principles of collaborative governance, where multiple stakeholders work together in consensus-orientated decision-making, particularly in public service settings [62]. While governance appears promising, several factors challenge effective governance, including a lack of trust in local leadership due to leadership instability and the implementation of misaligned policies that hinder collaboration. As one participant stated, “Many of our superiors, especially the directors, do not trust officers even though we are in positions that require expert knowledge” (DeptBInt6, 23:55–28:51). This highlights the need for a strategic alignment among policymakers, public sector officials, and IT experts to ensure a sound value co-creation strategy is established and sustained [36].

According to Rossi and Tuurnas [37], strategic decisions result from a proper governance structure aligned with systemic goals. Therefore, a proposed method for co-creation will integrate co-design and collaborative decision-making models, thus empowering and ensuring that stakeholders contribute to the service design [36]. Also, collaborative governance approaches are needed to identify key actors in co-creating value, align sectoral strategies with co-creation e-services and foster sustainable e-government initiatives through public–private partnerships (PPPs). Collaboration and communication result from strong leadership, encouraging stakeholders’ engagement and being willing to create a culture towards innovation [17].

Furthermore, cross-sector collaboration enhances actors in both the private and public sectors, allowing them to combine their ideas to innovate and share resources to deliver digital services more effectively [32]. A collaborative governance approach is recommended to map key stakeholders, identify the roles of various actors in value co-creation, and establish a PPP to ensure long-term sustainability for e-government initiatives [63].

4.3. Digital Transformation and the Agile and Participatory Approaches

Overall, the interview data highlighted the need for context-sensitive data governance to address fragmented systems and promote local ownership. Multilingual platforms were key for effective participation, especially in Bislama-English contexts. Participants also relied on low-tech tools like WhatsApp, SMS, and Smartsheet due to infrastructure and connectivity limitations. These findings stress the value of inclusive, locally adapted digital solutions in driving transformation in SIDNs.

According to the findings, the way data is governed, its associated issues, the tools used for governing, collecting, and analysing data to provide optimisation, and how technology is integrated and utilised to enable services are critical to digital transformation. Effective data governance and integrated digital systems are widely acknowledged as essential pillars to digital transformation, particularly in small island and developing contexts where interoperability and informed decision-making are crucial [2]. Data governance and integrated technology are the way forward; however, factors such as data accuracy, reluctance to share data and information, and system inefficiencies impact digital transformation. One participant stated, “They are reluctant to share government properties like data with others due to a negative experience they previously had” (DeptBInt4, 21:22–22:15).

Stakeholders can share data if they are part of the transformation and being part of the participatory practices will avoid resistance and conceptual confusion [27]. According to Al Maazmi, Piya and Araci [17], digital transformation requires participatory and agile methods and strong stakeholder engagement, strengthening data governance and interoperability through standardised data exchange protocols.

4.4. Technology Readiness and the Technology Adaptation Approach

Overall, the interview data highlighted resilience and technological readiness building as prerequisites to sustainable e-governance services. Encouraging modern approaches such as agile service development and advanced technological solutions (e.g., cloud technologies) was seen as a risk reduction measure ensuring long-term service maintenance and service sustainability.

Resilience and readiness are prerequisites for successful co-creation. Technological infrastructure, technical empowerment, capacity building, and technological integration contribute to innovation and readiness. The challenges found in the results indicate that technological infrastructure challenges disrupt digital service delivery. One participant pointed out that, “One of the challenges we faced was vandalism on the stations. The stations are cut and broken and demand even steel parts” (DeptBInt5, 05:55–07:21). Technical capacity gaps were also found to be a challenge that hinders e-service initiatives and maintenance, as noted, “We lack IT human resources developers […] they take time to develop it or will try but cannot finish it” (DeptBInt3, 23:53–26:03).

Real-time data integration, creating sustainable and resilient service delivery that adds value to citizens, can only happen if the infrastructures are addressed with workable and training capacity solutions, despite the limited resources [32]. According to Yildiz and Sağsan [10], building a multi-platform technology integration helps build a resilient citizen-centric government system in this vulnerable and dynamic context. Hence, a resilient model would uphold security, build internal expertise, and develop financial programs through PPP, enabling long-term system maintenance and sustainability. A technology adaptation model is recommended; it makes use of agile development for iterative improvements, using cloud-based solutions for scalability, security and service products based on real-time data [4,20].

4.5. Sustainability and the Sociotechnical Systems Approach

Overall, the interview findings suggest the need for donor-aligned but locally driven implementation, as projects often faltered without strong local leadership. Participants also highlighted resource pooling and shared infrastructure use to address inefficiencies and duplication across ministries. Ensuring long-term success was linked to local capacity building for post-donor sustainability, emphasising the importance of upskilling local teams. Together, these insights highlight the importance of grounded, collaborative strategies for sustaining e-government services.

Partnership, capacity building, and sustainability are of great importance to participatory and co-design methods. They emphasise strategic partnerships, long-term collaborative resource and financial adjustments, and jointly build capacity and optimise the workforce to support the co-creation of value and e-government services initiatives. Findings did show that limited budget allocations and over-reliance on external funding pose a risk to continuity, as one participant stated, “The budget is small to run those very expensive scientific equipment” (DeptBInt4, 46:56–51:24).

Likewise, the shortages of human resources lead to skills mismatches affecting the expansion of e-government services, as one stated, “We plan to expand the observation to marine, but we need more human capacity” (DeptBInt7, 33:22–33:50). Therefore, the recommendation is that a capacity and financial sustainability model be implemented, integrating cost-sharing mechanisms through multi-stakeholder partnerships and engagement [25], long-term capacity and workforce development [18] and training programs to improve levels and bridge technology skill gaps [21], and to ensure financial accountability through a performance-based model [10].

To ensure long-term sustainability, a balanced integration of human and technological investments is needed, and in our case, the human resource investments, sustainable funding streams through public and private contributions, and fostering localised e-government solutions, a sociotechnical system approach to value co-creation is recommended [64]. Through a cyclical process, the sustainability and accessibility of e-government services will be consistently maintained, adding value to stakeholders.

4.6. Cross-Cutting Contextual Factors in SIDNs