Emotional Responses to Racial Violence: Analyzing Sentiments and Emotions Among Black Women in Missouri

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Racial Violence in the Lives of Black Women

1.1.1. Racial Violence and Black Women

1.1.2. Racial Violence and Sentiment Analysis

1.1.3. Racial Violence and Emotion Analysis

1.2. Broadening the Metrics of Racial Violence

1.2.1. Racial Violence Measurement

1.2.2. Racial Violence and Sentiment Analysis Measurement

1.2.3. Racial Violence and Emotion Analysis Measurement

1.2.4. MAACL-R and Sentiment Analysis

1.2.5. MAACL-R and Emotion Analysis

1.3. Sentiment Analysis and Racial Violence

1.4. Emotion Analysis and Racial Violence

1.5. Theorizing Emotional Reactions to Racial Violence

Racial Trauma Theory

- As measured through self-reported data and computational analysis, what sentiments and emotions do Black women in Missouri express regarding incidents of racial violence?

- What contextual or psychosocial factors may account for the expression of positive sentiments and emotions regarding incidents of racial violence?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographics

2.3.2. Racial Violence

2.3.3. Sentiment Analysis

2.3.4. Emotion Analysis

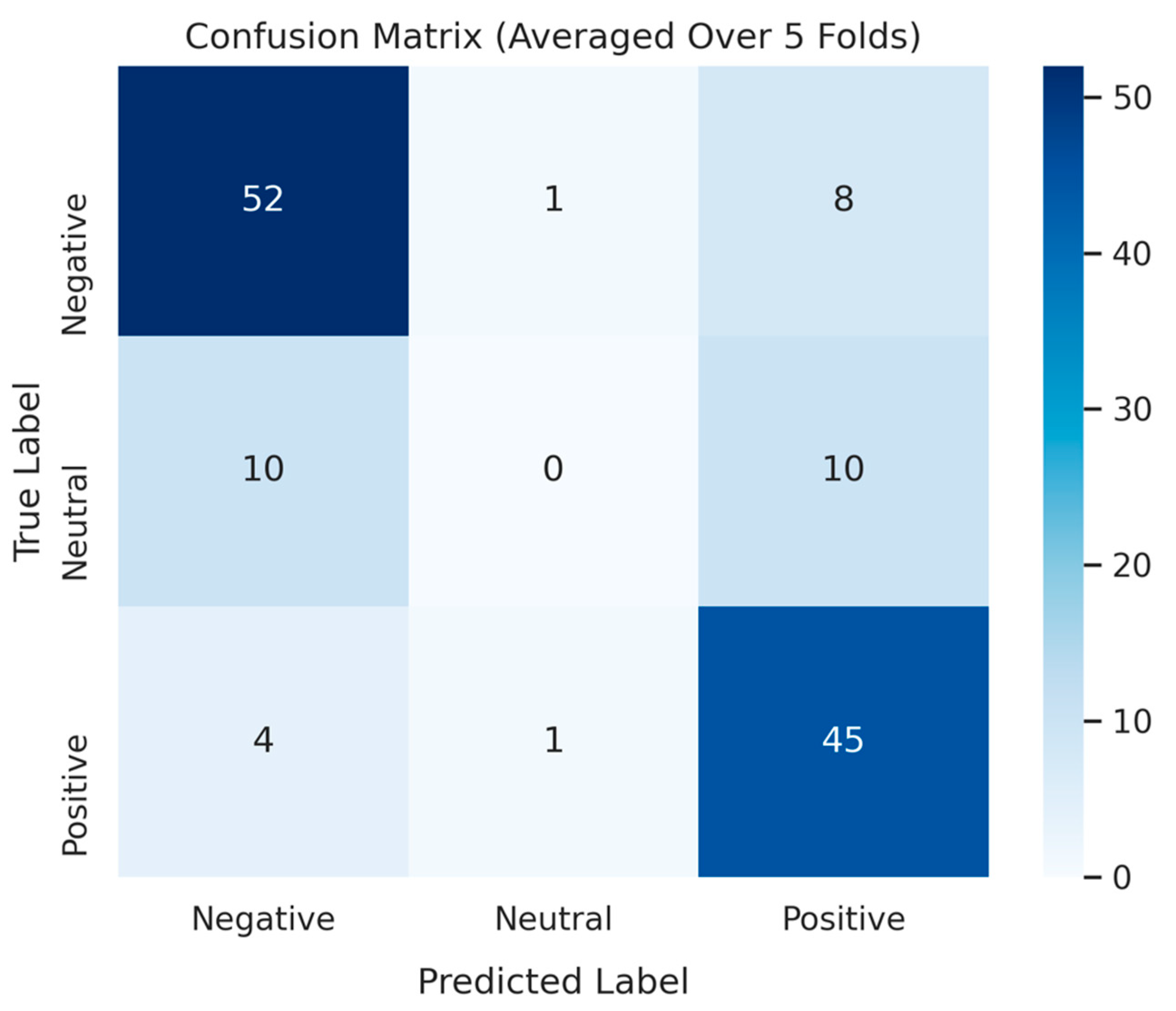

2.3.5. RoBERTa

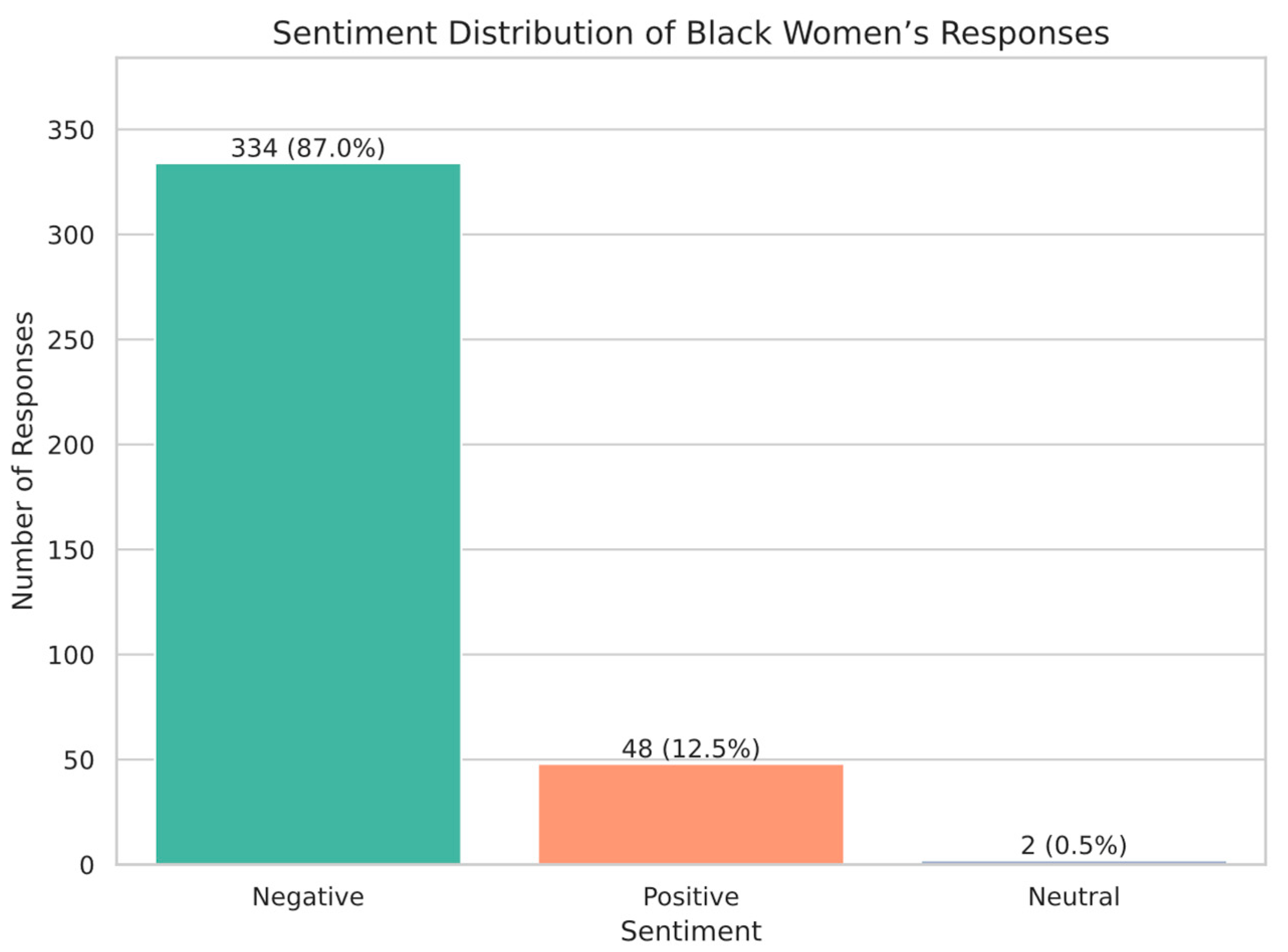

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Negative Emotions and Racial Violence Among Black Women in Missouri

4.2. Neutral Emotions and Racial Violence Among Black Women in Missouri

4.3. Positive Emotions and Racial Violence Among Black Women in Missouri

4.4. Examining Factors Contributing to Positive Emotions Among Black Women in Missouri

4.4.1. Coping Mechanisms

4.4.2. Racial Identity Beliefs

4.4.3. Spirituality and Religiosity

4.4.4. Resilience and Strength

4.5. Public Health and Clinical Implications

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MAACL-R | Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist-Revised |

| VADER | Valence Aware Dictionary and sEntiment Reasoner |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| REMS | Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale |

| EDS | Everyday Discrimination Scale |

| IRRS | Index of Race-Related Stress |

| RoBERTa | Robustly Optimized BERT Approach |

| SBW | Strong Black Woman |

References

- Blee, K.M. Racial violence in the United States. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2005, 28, 599–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, D.S.; Washburn, T.; Lee, H.; Smith, K.R.; Kim, J.; Martz, C.D.; Kramer, M.R.; Chae, D.H. Highly public anti-Black violence is associated with poor mental health days for Black Americans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2019624118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FBI. 2022 FBI Hate Crime Statistics. U.S. Department of Justice. 2023. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/crs/highlights/2022-hate-crime-statistics (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Cox, K. Racial Discrimination Shapes how Black Americans View Their Progress and U.S. Institutions. Pew Research Center. 2024. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2024/06/15/racial-discrimination-shapes-how-black-americans-view-their-progress-and-u-s-institutions-2/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Racism and Health I: Pathways and Scientific Evidence. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1152–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, R.M.; Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Contemp. Sociol. 1992, 21, 132–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black Feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. In Feminist Legal Theories; Taylor and Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 1998; pp. 314–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; James, K.F.; Méndez, D.D.; Johnson, R.; Davis, E.M. The wear and tear of racism: Self-silencing from the perspective of young Black women. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2023, 3, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisgin, N.; Bisgin, H.; Hummel, D.; Zelner, J.; Needham, B.L. Did the public attribute the Flint Water Crisis to racism as it was happening? Text analysis of Twitter data to examine causal attributions to racism during a public health crisis. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 2022, 6, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanayakkara, A.C.; Kumara, B.T.G.S. Analyzing discourse and sentiment surrounding social justice movements: A case study of the Black Lives Matter Movement. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2025, 2, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Merchant, J.S.; Yue, X.; Mane, H.; Wei, H.; Huang, D.; Gowda, K.N.; Makres, K.; Najib, C.; Nghiem, H.T.; et al. A Decade of Tweets: Visualizing racial sentiments towards minoritized groups in the United States between 2011 and 2021. Epidemiology 2023, 35, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.T.; Carpenter, N.J. Sharing #MeToo on Twitter: Incidents, coping responses, and social reactions. Equal. Divers. Incl. 2019, 39, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujah, O.I.; Olaore, P.; Nnorom, O.C.; Ogbu, C.E.; Kirby, R.S. Examining ethno-racial attitudes of the public in Twitter discourses related to the United States Supreme Court Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling: A machine learning approach. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2023, 4, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essed, P. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K.W.; Ritchie, A.J.; Anspach, R.; Gilmer, R.; Harris, L. Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women. Scholarship Archive. 2015. Available online: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/3226 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Fluker, J.L. The Liberating Narrative of #SayHerName: A Womanist Social Justice Movement in Black Women’s Stories. Currents in Theology and Mission. 2022. Available online: https://currentsjournal.org/index.php/currents/article/view/334 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Nandwani, P.; Verma, R. A review on sentiment analysis and emotion detection from text. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2021, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, I.; Sargent, E.; Peoples, J.; Butler-Barnes, S.T.; Leath, S. “Uncovering Responses”: A Sentiment Analysis approach to racial violence among Black parents in Missouri. SAGE Open 2025, 15, 2158244025133314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.; Park, C.Y.; Theophilo, A.; Watson-Daniels, J.; Tsvetkov, Y. An analysis of emotions and the prominence of positivity in #BlackLivesMatter tweets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2205767119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal, K.L.; Griffin, K.E.; Wong, Y.; Hamit, S.; Rasmus, M. The impact of racial microaggressions on mental health: Counseling implications for clients of color. J. Couns. Dev. 2014, 92, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Yu, N.Y.; Jackson, J.S.; Anderson, N.B. Racial differences in physical and mental health. J. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsey, S.O. Development and validation of a short form of the Index of Race-Related Stress (IRRS)—Brief Version. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 1999, 32, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.T.; Cogburn, C.D.; Williams, D.R. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: Scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 11, 407–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ibánez, M.; Casánez-Ventura, A.; Castejón-Mateos, F.; Cuenca-Jiménez, P. A review on sentiment analysis from social media platforms. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 223, 119862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, N.V.; Kanaga, E.G.M. Sentiment analysis in social media data for depression detection using artificial intelligence: A review. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, M.; Sathiskumar, V.E.; Deepalakshmi, G.; Cho, J.; Manikandan, G. A survey on hate speech detection and sentiment analysis using machine learning and deep learning models. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 80, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alslaity, A.; Orji, R. Machine learning techniques for emotion detection and sentiment analysis: Current state, challenges, and future directions. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 43, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaube, N.; Kerketta, R.; Sharma, S.; Shinde, A. The role of affective computing in social justice: Harnessing equity and inclusion. In Affective Computing for Social Good; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT). Understanding the Impact of Trauma. Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services—NCBI Bookshelf. 2014. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191/#:~:text=Somatization,traumatic%20stress%20reactions%2C%20including%20PTSD (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Zuckerman, M.; Lubin, B.; Rinck, C.M. Multiple Affect Adjective Check List—Revised (MAACL-R). [Database Record]. APA PsycTests 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.F.; Lindquist, K.A.; Gendron, M. Language as context for the perception of emotion. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusal, S.; Patil, S.; Choudrie, J.; Kotecha, K.; Vora, D.; Pappas, I. A systematic review of applications of natural language processing and future challenges with special emphasis in text-based emotion detection. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 15129–15215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y. The Authors. Sentiment analysis methods, applications, and challenges: A systematic literature review. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, J.R.; Talukder, M.A.R.; Malakar, P.; Kabir, M.M.; Nur, K.; Mridha, M.F. Recent advancements and challenges of NLP-based sentiment analysis: A state-of-the-art review. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2024, 6, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamibekr, M.; Ghorbani, A.A. Sentiment Analysis of Social Issues. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Social Informatics, Alexandria, VA, USA, 14–16 December 2012; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6542443 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Jiang, L.; Suzuki, Y. Detecting Hate Speech from Tweets for Sentiment Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Systems and Informatics (ICSAI), Shanghai, China, 2–4 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 4 November 2019. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9010578 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. VADER: A Parsimonious Rule-Based Model for Sentiment Analysis of Social Media Text. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1–4 June 2014; Volume 8, pp. 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, J.G.; Ebeling, R.; Becker, K. A framework to analyze the emotional reactions to mass violent events on Twitter and influential factors. Inf. Process. Manag. 2020, 57, 102372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.C.T.; Lee, D.B.; Gaskin, A.L.; Neblett, E.W. Emotional response profiles to racial discrimination. J. Black Psychol. 2013, 40, 334–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, M.E.; Ibrahim, S.; Schiller, D.; Delgado, M.R. Finding positive meaning in memories of negative events adaptively updates memory. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.M.; Turney, P.D. Crowdsourcing a word-emotion association lexicon. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1308.6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Pu, P.; Jiang, L. Emotion-RGC net: A novel approach for emotion recognition in social media using RoBERTa and Graph Neural Networks. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machová, K.; Szabóova, M.; Paralič, J.; Mičko, J. Detection of emotion by text analysis using machine learning. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1190326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NAACP. NAACP Travel Advisory for the State of Missouri; 2017. Available online: https://naacp.org/resources/naacp-travel-advisory-state-missouri (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Potterf, J.E.; Pohl, J.R. A Black teen, a White cop, and a city in turmoil: Analyzing newspaper reports on Ferguson, Missouri and the death of Michael Brown. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2018, 34, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.T. Racism and psychological and emotional injury. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 35, 13–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M. Complex racial trauma: Evidence, theory, assessment, and treatment. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 18, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Díaz, L.; Hall, G.N.; Neville, H.A. Racial trauma: Theory, research, and healing: Introduction to the special issue. Am. Psychol. 2019, 74, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.E.; Gibbons, F.X.; Beach, S.R.H. Measuring the biological embedding of racial trauma among Black Americans utilizing the RDoC approach. Dev. Psychopathol. 2021, 33, 1849–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Justice. Learn About Hate Crimes. 2024. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/hatecrimes/learn-about-hate-crimes (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- FBI. 2023 FBI Hate Crimes Statistics. 2025. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/crs/news/2023-hate-crime-statistics (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Banaji, M.R.; Fiske, S.T.; Massey, D.S. Systemic racism: Individuals and interactions, institutions and society. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2021, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervin, K.K. Gateway to Equality: Black Women and the Struggle for Economic Justice in St. Louis; University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hugging Face. Cardiffnlp/Twitter-Roberta-Base-Sentiment. 2024. Available online: https://huggingface.co/cardiffnlp/twitter-roberta-base-sentiment (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Hugging Face. Bhadresh-Savani/Bert-Base-Go-Emotion. 2024. Available online: https://huggingface.co/bhadresh-savani/bert-base-go-emotion (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Lee, E.; Rustam, F.; Washington, P.B.; Barakaz, F.E.; Aljedaani, W.; Ashraf, I. Racism detection by analyzing differential opinions through sentiment analysis of tweets using stacked ensemble GCR-NN model. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 9717–9728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, D.S. “After Philando, I had to take a sick day to recover”: Psychological distress, trauma and police brutality in the Black community. Health Commun. 2021, 37, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. Stress and the mental health of populations of color: Advancing our understanding of race-related stressors. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2018, 59, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, Z.; Maqsood, M.H.; Yahya, T.; Amin, Z.; Acquah, I.; Valero-Elizondo, J.; Andrieni, J.; Dubey, P.; Jackson, R.K.; Daffin, M.A.; et al. Race, racism, and cardiovascular health: Applying a social determinants of health framework to racial/ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2022, 15, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradies, Y.; Ben, J.; Denson, N.; Elias, A.; Priest, N.; Pieterse, A.; Gupta, A.; Kelaher, M.; Gee, G. Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Neighbors, H. Racism, discrimination and hypertension: Evidence and needed research. Ethn. Dis. 2001, 11, 800–816. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45410332 (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Lei, M.K.; Lavner, J.A.; Carter, S.E.; Hart, A.R.; Beach, S.R.H. Protective parenting behavior buffers the impact of racial discrimination on depression among Black youth. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesne, J. Understanding the emotional toll of racial violence on Black individuals’ health. Societies 2024, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanco-Roman, L.; Danies, A.; Anglin, D.M. Racial discrimination as race-based trauma, coping strategies, and dissociative symptoms among emerging adults. Psychol. Trauma 2016, 8, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E.B.; Hearst-Ikeda, D. Emotional Dissociation in Response to Trauma; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrutyn, S. The roots of social trauma: Collective, cultural pain and its consequences. Soc. Ment. Health 2023, 14, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, K.; Asokumar, A.; Anisman, H. Resilience: Safety in the aftermath of traumatic stressor experiences. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 596919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, R.; Lopez, C.; Wade, L.; Castillo, L.G. Racial justice activist burnout of women of color in the United States: Practical tools for counselor intervention. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2021, 43, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Lorenzi, P.; Nardi, B.; Carmassi, C.; Carpita, B. Post traumatic growth (PTG) in the frame of traumatic experiences. PubMed 2022, 19, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riepenhausen, A.; Wackerhagen, C.; Reppmann, Z.C.; Deter, H.; Kalisch, R.; Veer, I.M.; Walter, H. Positive cognitive reappraisal in stress resilience, mental health, and well-being: A comprehensive systematic review. Emot. Rev. 2022, 14, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, A.S.; Shallcross, A.J.; Brunner, A.; Friedman, R.; Jones, M.C. Cognitive reappraisal and acceptance: Effects on emotion, physiology, and perceived cognitive costs. Emotion 2018, 18, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, H.A.; Sosoo, E.E.; Bernard, D.L.; Neal, A.; Neblett, E.W. The associations between internalized racism, racial identity, and psychological distress. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 9, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Neville, H.A.; Todd, N.R.; Mekawi, Y. Ignoring race and denying racism: A meta-analysis of the associations between colorblind racial ideology, anti-Blackness, and other variables antithetical to racial justice. J. Couns. Psychol. 2022, 70, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchus, D.N.A.; Holley, L.C. Spirituality as a coping resource. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work 2004, 13, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, A.K.; Hayman, L.L. Unveiling the Strong Black Woman Schema—Evolution and impact: A systematic review. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2024, 33, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyiwo, N.; Stanton, A.G.; Avery, L.R.; Bernard, D.L.; Abrams, J.A.; Golden, A. Becoming strong: Sociocultural experiences, mental health, & Black girls’ Strong Black Woman Schema endorsement. J. Res. Adolesc. 2021, 32, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods-Giscombé, C.L. Superwoman Schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qual. Health Res. 2010, 20, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyton, T.; Johnson, N.; Ross, K. ‘I’m good’: Examining the internalization of the Strong Black Woman archetype. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2020, 32, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.04 | 3.835 |

| Education 1 | 4.28 | 0.693 |

| Income | 2.14 | 0.516 |

| Fold | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.666667 | 0.641667 | 0.666667 | 0.633222 |

| 2 | 0.692308 | 0.609391 | 0.692308 | 0.648070 |

| 3 | 0.807692 | 0.686391 | 0.807692 | 0.740602 |

| 4 | 0.807692 | 0.686391 | 0.807692 | 0.740602 |

| 5 | 0.730769 | 0.625000 | 0.730769 | 0.670330 |

| Average | 0.741026 | 0.649768 | 0.741026 | 0.686565 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smith, I.; Butler-Barnes, S.T. Emotional Responses to Racial Violence: Analyzing Sentiments and Emotions Among Black Women in Missouri. Information 2025, 16, 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070598

Smith I, Butler-Barnes ST. Emotional Responses to Racial Violence: Analyzing Sentiments and Emotions Among Black Women in Missouri. Information. 2025; 16(7):598. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070598

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith, Ivy, and Sheretta T. Butler-Barnes. 2025. "Emotional Responses to Racial Violence: Analyzing Sentiments and Emotions Among Black Women in Missouri" Information 16, no. 7: 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070598

APA StyleSmith, I., & Butler-Barnes, S. T. (2025). Emotional Responses to Racial Violence: Analyzing Sentiments and Emotions Among Black Women in Missouri. Information, 16(7), 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070598