The Effect of Organizational Factors on the Mitigation of Information Security Insider Threats

Abstract

1. Introduction

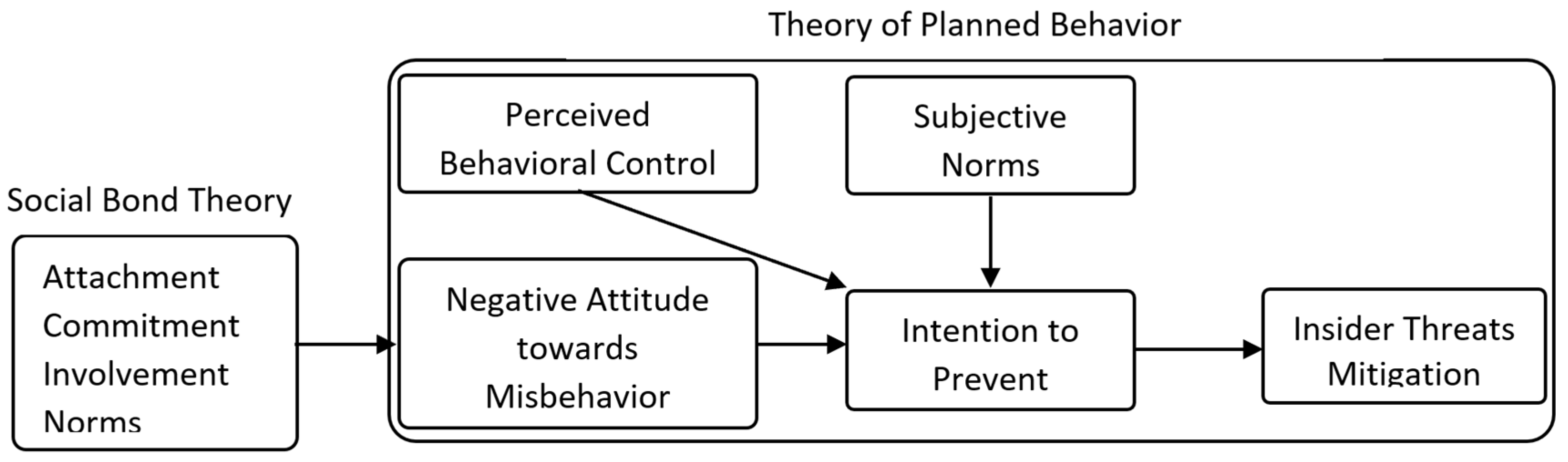

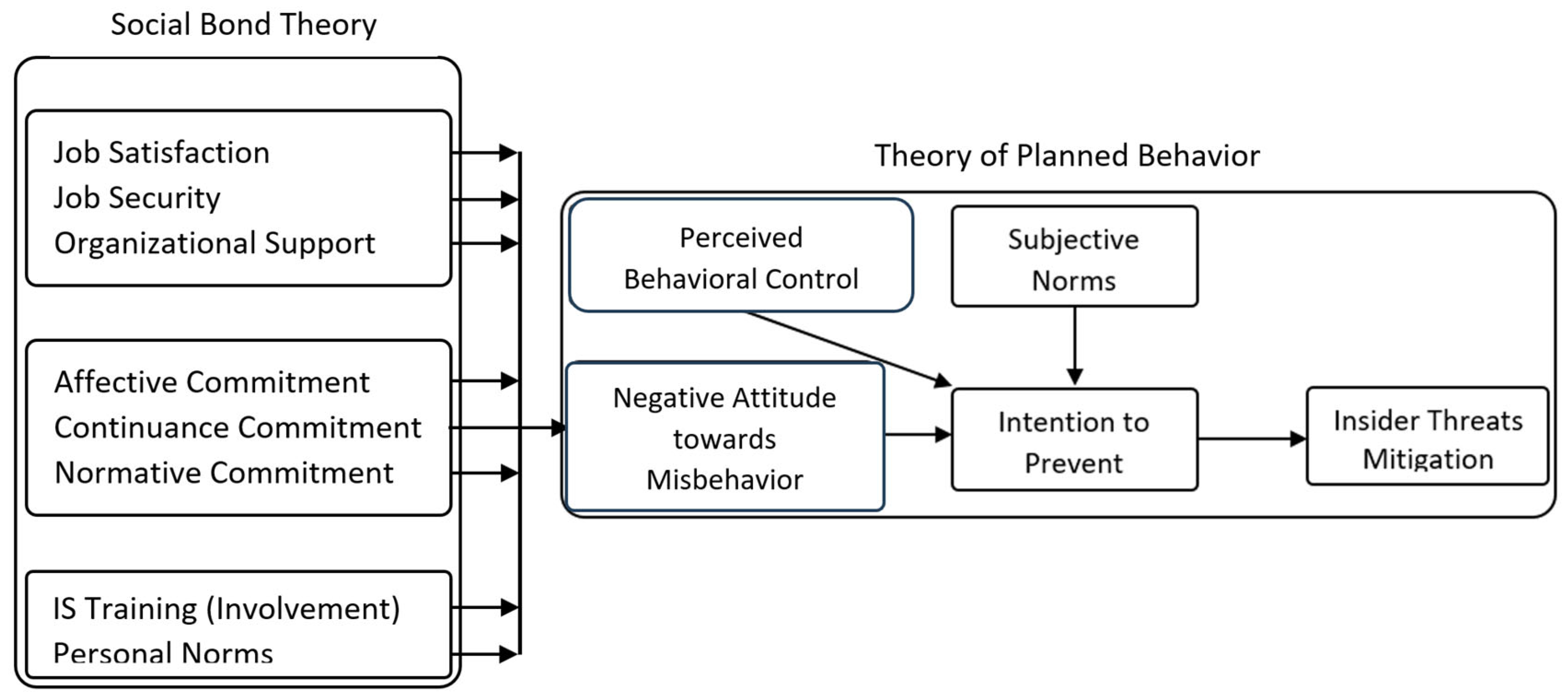

2. The Theoretical Background

2.1. Social Bond Theory

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.3. Research Gap and Justification

3. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Job Satisfaction

3.2. Job Security

3.3. Organizational Support

3.4. Affective Commitment

3.5. Continuance Commitment

3.6. Normative Commitment

3.7. IS Training

3.8. Personal Norms

3.9. Attitude

3.10. Perceived Behavioral Control

3.11. Subjective Norms

3.12. Intention

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Demography

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Model

5.2. Testing Structural Model

6. Contribution and Implementation

7. Conclusions, Limitation, and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colabianchi, S.; Costantino, F.; Nonino, F.; Palombi, G. Transforming threats into opportunities: The role of human factors in enhancing cybersecurity. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padayachee, K. Aspectising honeytokens to contain the insider threat. Inf. Secur. IET 2015, 9, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, N.S.; Maple, C.; Furnell, S.; Azad, M.A.; Perera, C.; Dabbagh, M.; Sookhak, M. Deterrence and prevention-based model to mitigate information security insider threats in organisations. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 97, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Matari, O.M.M.; Helal, I.M.A.; Mazen, S.A.; Elhennawy, S. Adopting security maturity model to the organizations’ capability model. Egypt. Inform. J. 2020, 22, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniuk, E.K.; Szczepaniuk, H.; Rokicki, T.; Klepacki, B. Information security assessment in public administration. Comput. Secur. 2020, 90, 101709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, N.S.; Maple, C.; Watson, T.; Von Solms, R. Motivation and opportunity based model to reduce information security insider threats in organisations. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2018, 40, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, N.; Liang, H. Motivating information security policy compliance: The critical role of supervisor-subordinate guanxi and organizational commitment. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.; Arshah, R.A.; Hamid, M.R.A.; Fahmy, S. An analysis on the dimensions of information security culture concept: A review. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2019, 44, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlutürk, M.; Wynn, M.; Metin, B. Phishing and the Human Factor: Insights from a Bibliometric Analysis. Information 2024, 15, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifinedo, P. Understanding information systems security policy compliance: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. Comput. Secur. 2012, 31, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, T. Causes of Delinquency; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Xu, X.; Arpan, L. Between the technology acceptance model and sustainable energy technology acceptance model: Investigating smart meter acceptance in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 25, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepasgozar, S.M.E.; Hawken, S.; Sargolzaei, S.; Foroozanfa, M. Implementing citizen centric technology in developing smart cities: A model for predicting the acceptance of urban technologies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 142, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi Safa, N.; Von Solms, R.; Furnell, S. Information security policy compliance model in organizations. Comput. Secur. 2016, 56, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, N.S.; Sookhak, M.; Von Solms, R.; Furnell, S.; Ghani, N.A.; Herawan, T. Information security conscious care behaviour formation in organizations. Comput. Secur. 2015, 53, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifinedo, P. Information systems security policy compliance: An empirical study of the effects of socialisation, influence, and cognition. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang-Pham, D.; Pittayachawan, S.; Bruno, V. Exploring behavioral information security networks in an organizational context: An empirical case study. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2017, 34, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Holm, E.; Zhai, Q. Understanding the violation of IS security policy in organizations: An integrated model based on social control and deterrence theory. Comput. Secur. 2013, 39 Pt B, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, N.S.; Maple, C.; Watson, T.; Furnell, S. Information security collaboration formation in organisations. IET Inf. Secur. 2017, 12, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Maglaras, L.A.; He, Y.; Janicke, H. Human behaviour as an aspect of cybersecurity assurance. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2016, 9, 4667–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, N.S.; Von Solms, R. An information security knowledge sharing model in organizations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikoff, R.C.; Costigan, S.A.; Karunamuni, N.; Lubans, D.R. Social cognitive theories used to explain physical activity behavior in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2013, 56, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hau, Y.S.; Kim, B.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.-G. The effects of individual motivations and social capital on employees’ tacit and explicit knowledge sharing intentions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepler, J. A good thing isn’t always a good thing: Dispositional attitudes predict non-normative judgments. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 75, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, S.; Kovacs, C. Educational Psychology: Using Insights from Implicit Attitude Measures. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 25, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abawajy, J. User preference of cyber security awareness delivery methods. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2014, 33, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Mubarak, S. MEASURING HUMAN RESOURCE ATTITUDE USING ORGANISATIONAL THEORY OF RELATIONSHIP: THE WAY FORWARD. Int. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 28, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jigjiddorj, S.; Zanabazar, A.; Jambal, T.; Semjid, B. Relationship Between Organizational Culture, Employee Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 90, 02004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, A.C.; Warkentin, M. Fear appeals and information security behaviors: An empirical study. MIS Q. 2010, 34, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siponen, M.; Mahmood, M.A.; Pahnila, S. Employees’ adherence to information security policies: An exploratory field study. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezdrob, M.; Šunje, A. Transient nature of the employees’ job satisfaction: The case of the IT industry in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Mishra, S.; Kumar Jain, T. An analysis to understanding the job satisfaction of employees in banking industry. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 37, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliyana, A.; Ma’arif, S. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment effect in the transformational leadership towards employee performance. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 25, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowbray, O.; Campbell, R.D.; Disney, L.; Lee, M.; Fatehi, M.; Scheyett, A. Peer support provision and job satisfaction among certified peer specialists. Soc. Work Ment. Health 2021, 19, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, S.; Abugre, J. The Influence of Rewards and Job Satisfaction on Employees in the Service Industry; Centre for Business & Economic Research: London, UK, 2013; pp. 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, K.Z.B.; Jasimuddin, S.M.; Kee, W.L. Organizational climate and job satisfaction: Do employees’ personalities matter? Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inayat, U.; Farzan, M.; Mahmood, S.; Zia, M.F.; Hussain, S.; Pallonetto, F. Insider threat mitigation: Systematic literature review. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Zo, H. Preventing insider threats to enhance organizational security: The role of opportunity-reducing techniques. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 63, 101670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, V. Systematic literature review on insider threat: Is the Australian aviation industry complacent or just not understanding insider threat? J. Air Transp. Res. Soc. 2025, 4, 100060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Huang, S.; Hou, P. Emotional intelligence, emotional labor, perceived organizational support, and job satisfaction: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgunduz, Y.; Alkan, C.; Gök, Ö.A. Perceived organizational support, employee creativity and proactive personality: The mediating effect of meaning of work. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 34, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, R.; Lin, X.; Tan, A.J.M. Powered to craft? The roles of flexibility and perceived organizational support. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang-Pham, D.; Thompson, N.; Ahmed, A.; Maynard, S. Shadow Information Security Practices in Organizations: The role of information security transparency, overload, and psychological empowerment. Comput. Secur. 2025, 156, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Amarnani, R.K.; Bordia, P.; Restubog, S.L.D. When support is unwanted: The role of psychological contract type and perceived organizational support in predicting bridge employment intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 125, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Hao, S.; Li, G.; Liang, X.; Chen, T.; Feng, X. The impact of organizational support on employee performance. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 42, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TorlakTorlak, N.G.G.; BudurBudur, T.; KhanKhan, N.U.S.U.S. Links connecting organizational socialization, affective commitment and innovative work behavior. Learn. Organ. 2024, 31, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.F.; Riemenschneider, C.K.; Allen, M.W.; Armstrong, D.J. Information Technology Employees in State Government: A Study of Affective Organizational Commitment, Job Involvement, and Job Satisfaction. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2008, 38, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H. The incremental validity of organizational commitment, organizational trust, and organizational identification. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 88, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahyun, G.; Myung-Seong, Y.; Kim, D.J. A Path to Successful Management of Employee Security Compliance: An Empirical Study of Information Security Climate. Prof. Commun. IEEE Trans. 2014, 57, 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Parfyonova, N.M. Normative commitment in the workplace: A theoretical analysis and re-conceptualization. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakı, N.; Asfuroglu, L.; Erbas, O. The Relationship between the Level of Attachment in Romantic Relations, Affective Commitment and Continuance Commitment towards Organization: A Field Research. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 26, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.M.M.R.; Bashir, S. IT-expert retention through organizational commitment: A study of public sector information technology professionals in Pakistan. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2015, 11, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D.M.; Meyer, J.P. Side-bet theory and the three-component model of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalck, N.; Rolan, L.; Kellermanns, F.W. The continuance commitment of family firm CEOs. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2023, 14, 100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.; Chengalur-Smith, I. Evaluating the effectiveness of learner controlled information security training. Comput. Secur. 2019, 87, 101586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, D.D.; Pfleeger, S.L.; Freeman, J.D.; Johnson, M.E. Going spear phishing: Exploring embedded training and awareness. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2014, 12, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartnes, M.; Moe, N.B.; Heegaard, P.E. The future of information security incident management training: A case study of electrical power companies. Comput. Secur. 2016, 61, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, N.S.; Mitchell, F.; Maple, C.; Azad, M.A.; Dabbagh, M. Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs) for connected vehicles in smart cities. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2020, 33, e4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.I.d.A. Conceptualization and measurement of personal norms regarding meal preparation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Sarathy, R. Understanding compliance with internet use policy from the perspective of rational choice theory. Decis. Support Syst. 2010, 48, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattinson, M.; Parsons, K.; Butavicius, M.; McCormac, A.; Calic, D. Assessing information security attitudes: A comparison of two studies. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2016, 24, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Kim, Y.G.; Koh, J. An integrative model for knowledge sharing in communities-of-practice. J. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 15, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, H.J.; Jewell, L.N. Sex, Locus of Control, and Job Involvement. H. Joseph Reitz, Faculty, University of Florida, and Linda N. Jewell, Faculty, University of California-Irvine. Abstract from Academy of Management Journal, March 1979, p. 72. Int. Exec. 1979, 21, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, M.; Bommer, W.H.; Straub, D. Security lapses and the omission of information security measures: A threat control model and empirical test. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 2799–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, S.-M.; Chou, C.-H.; Liao, H.-L. A study of Facebook Groups members’ knowledge sharing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1971–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibchurn, J.; Yan, X. Information disclosure on social networking sites: An intrinsic–extrinsic motivation perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 44, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamjidyamcholo, A.; Bin Baba, M.S.; Shuib, N.L.M.; Rohani, V.A. Evaluation model for knowledge sharing in information security professional virtual community. Comput. Secur. 2014, 43, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-K. The temporal relationships among habit, intention and IS uses. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 32, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astington, J. The Child’s Discovery of the Mind; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Shropshire, J.; Warkentin, M.; Sharma, S. Personality, attitudes, and intentions: Predicting initial adoption of information security behavior. Comput. Secur. 2015, 49, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Gu, B.; Leung, A.C.M.; Konana, P. An investigation of information sharing and seeking behaviors in online investment communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 785. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos 16.0 User’s Guide; SPSS, Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| Factors | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Job Satisfaction (JS) | JS is a measure of employees’ contentedness with their job and originates from respect, recognition, fair compensation, and motivation. |

| 2 | Job Security (JSe) | JSe refers to the probability of keeping a job. In other words, there is a small chance of losing a job. |

| 3 | Organizational Support (OS) | OS refers to the employees’ perception that the organization cares about their well-being and values their contribution. |

| 4 | Affective Commitment (AC) | AC shows that employees feel that they are part of the organization and like it. A good working experience is an important factor in this regard. |

| 5 | Continuance Commitment (CC) | CC refers to the cost of leaving an organization for the employee. The result of cost and benefit assessment motivates employees to stay and maintain their commitment or leave the organization. |

| 6 | Normative Commitment (NC) | NC refers to the employees’ decision without any external obligation. NC is built upon duties and values. |

| 7 | IS Training (IST) | IST refers to all types of information security training that an employer provides for its employees. |

| 8 | Personal Norms (PN) | PN refers to the values and moral obligations in which an individual believes. |

| 9 | Attitude (AT) | AT refers to an individual’s tendency about feeling, emotion, position, that they have about a person or things. |

| 10 | Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) | PBC refers to having a perception of the ability to complete a task. In this study—the ability to avoid any information security risk, considering legitimate access to systems and data. |

| 11 | Subjective Norms (SN) | SN refers to the belief that a group of people or important persons will approve and support a particular behavior. |

| 12 | Intention (IN) | IN refers to an assumption that explains a commitment to carrying out an action now or in the future. |

| 13 | Insider Threat (ITh) | ITh refers to abuse of legitimate access to systems and data for financial benefits or other reasons. |

| Measure | Items | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 336 | 69.78 |

| Female | 146 | 30.22 | |

| Age | 21 to 30 | 160 | 29.98 |

| 31 to 40 | 195 | 32.92 | |

| 41 to 50 | 85 | 25.06 | |

| Above 50 | 42 | 12.04 | |

| Position | Employee | 438 | 92.38 |

| Chief employee | 32 | 5.16 | |

| Management | 12 | 2.46 | |

| Work experience | 1 to 2 years | 128 | 16.71 |

| 3 to 5 years | 248 | 51.35 | |

| Above 5 years | 106 | 31.94 | |

| Education | Diploma | 38 | 7.86 |

| Bachelor | 306 | 71.25 | |

| Master | 114 | 18.92 | |

| PhD | 24 | 1.97 |

| Construct | Items | Mean | Std Dev | CFA Loading | Composite Reliability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Satisfaction [34,47] | JS1 | My employer recognizes my effort. | 4.32 | 0.762 | 0.632 | 0.736 |

| JS2 | My employer respects me for my work. | 4.02 | 0.782 | 0.522 | ||

| JS3 | My employer acknowledges my achievements. | 3.98 | 0.746 | Dropped | ||

| JS4 | My employer appreciates when I have a good performance. | 3.68 | 0.764 | 0.672 | ||

| JS5 | I am happy with my job. | 3.42 | 0.702 | 0.634 | ||

| Job Security [33] | JSE1 | I can work in this company for a long time. | 4.22 | 0.729 | 0.720 | 0.814 |

| JSE2 | The probability of losing my job is low. | 4.26 | 0.745 | 0.547 | ||

| JSE3 | I can keep my job. | 4.02 | 0.744 | 0.732 | ||

| JSE4 | I am not concerned about losing my job. | 3.96 | 0.782 | 0.764 | ||

| Perceived Organizational Support [42] | POS1 | My employer cares about my well-being. | 4.16 | 0.762 | 0.726 | 0.724 |

| POS2 | My employer values my contribution. | 4.02 | 0.712 | 0.818 | ||

| POS3 | My socioemotional well-being is important to my employer. | 3.98 | 0.854 | 0.822 | ||

| POS4 | My employer provides anything that I need to complete my tasks. | 3.68 | 0.782 | Dropped | ||

| Affective Commitment [47,53] | AC1 | I try to play an important role in my organization. | 3.86 | 0.722 | 0.722 | 0.818 |

| AC2 | I would like to remain a part of this organization. | 4.12 | 0.864 | 0.621 | ||

| AC3 | I have positive emotions regarding my employer. | 3.96 | 0.826 | 0.742 | ||

| AC4 | I help to achieve organizational aims. | 4.02 | 0.724 | 0.812 | ||

| Continuance Commitment [55] | CC1 | I am happy with my income in this organization. | 4.04 | 0.716 | 0.732 | |

| CC2 | I will lose a lot if I leave this organization. | 4.16 | 0.722 | 0.588 | ||

| CC3 | The benefits of staying in this organization outweigh the costs of moving somewhere else. | 4.42 | 0.742 | 0.742 | 0.762 | |

| CC4 | I have good colleagues in this organization; that is why I will stay here. | 3.98 | 0.762 | 0.712 | ||

| Normative Commitment [52] | NC1 | My employer has invested in me, that is why I want to stay here. | 4.16 | 0.782 | 0.842 | |

| NC2 | My employer rewards to me encourage me to stay here. | 3.64 | 0.728 | 0.722 | 0.726 | |

| NC3 | My commitment to my employer originates from their care to me. | 3.34 | 0.708 | 0.763 | ||

| NC4 | My colleagues recommend to me to stay here. | 4.12 | 0.804 | 0.802 | ||

| IS Training [58] | IST1 | Information security trainings help me to avoid mistakes in this domain. | 3.24 | 0.818 | 0.732 | |

| IST2 | Information security trainings influence my attitude towards complying with policies and procedures. | 3.22 | 0.752 | 0.744 | 0.762 | |

| IST3 | Information security trainings help me to reduce information security risks. | 4.34 | 0.822 | 0.726 | ||

| IST4 | Information security trainings influence my understanding about risk and make me act better. | 3.64 | 0.722 | 0.642 | ||

| Personal Norms [62,63] | PN1 | Protection of organizational information assets is very important to me. | 4.62 | 0.742 | 0.722 | |

| PN2 | I believe that information security breaches have negative consequence for my organization. | 4.22 | 0.712 | 0.818 | ||

| PN3 | Protection of information is our duty. | 3.98 | 0.844 | 0.822 | 0.742 | |

| PN4 | I am aware of GDPR; that is why I should not commit information security misconduct. | 3.88 | 0.742 | Dropped | ||

| PN5 | COISPs are necessary to protect information assets. | 4.12 | 0.736 | 0.714 | ||

| Attitude [12,31] | AT1 | Protection of organizational information assets is a good practice. | 3.96 | 0.849 | 0.722 | 0.748 |

| AT2 | I should protect organizational information as much as I can. | 3.42 | 0.715 | 0.754 | ||

| AT3 | Protection of information is a wise practice. | 4.32 | 0.832 | 0.796 | ||

| AT4 | Protection of information is a valuable action. | 3.64 | 0.742 | 0.662 | ||

| Perceived Behavioral Control [12,67] | PBC1 | I have the necessary knowledge to protect organizational information. | 4.26 | 0.762 | 0.842 | 0.842 |

| PBC2 | I have the ability to protect our data and information. | 3.34 | 0.768 | 0.782 | ||

| PBC3 | Protection of organizational information is not a tough task. | 3.64 | 0.708 | 0.726 | ||

| PBC4 | I have the tools that I need to protect information in my organization. | 4.12 | 0.864 | 0.801 | ||

| Subjective Norms [12,69] | SN1 | We should protect organizational information. | 3.86 | 0.716 | 0.824 | 0.728 |

| SN2 | My line manager believes that information protection is a valuable culture. | 3.94 | 0.780 | 0.812 | ||

| SN3 | The management team in my company have a positive view on information protection. | 4.26 | 0.822 | 0.709 | ||

| SN4 | My colleagues encourage me to protect organizational information. | 4.12 | 0.726 | 0.718 | ||

| Intention to Mitigate Risks [12,73] | IN1 | I should protect organizational information. | 3.98 | 0.643 | 0.942 | 0.754 |

| IN2 | I am willing to protect organizational information. | 4.22 | 0.546 | 0.722 | ||

| IN3 | I help my colleagues to protect organizational information. | 4.32 | 0.782 | Dropped | ||

| IN4 | I am committed to protecting organizational information. | 3.48 | 0.844 | 0.732 | ||

| IN5 | I put an effort into reducing information security risks. | 4.24 | 0.702 | 0.62 | ||

| Insider Threats Mitigation [15] | ITM1 | I do not abuse my legitimate access to systems. | 4.48 | 0.826 | 0.712 | |

| ITM2 | I do not transfer organizational data outside of my organizations. | 4.38 | 0.628 | 0.629 | ||

| ITM3 | I do not violate my organizational data protection regulations because of financial benefits. | 3.62 | 0.639 | 0.598 | 0.762 | |

| ITM4 | Protection of data about intellectual properties is important to me. | 4.24 | 0.802 | 0.706 | ||

| ITM5 | Protection of data about organizational plans is important to me. | 4.02 | 0.724 | 0.704 | ||

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | JS | 4.06 | 0.98 | 0.618 | ||||||||||

| 2 | JSE | 3.98 | 0.88 | 0.202 | 0.558 | |||||||||

| 3 | POS | 4.01 | 1.05 | 0.401 | 0.312 | 0.496 | ||||||||

| 4 | AC | 4.02 | 1.14 | 0.309 | 0.286 | 0.312 | 0.589 | |||||||

| 5 | CC | 3.98 | 1.02 | 0.289 | 0.404 | 0.470 | 0.265 | 0.488 | ||||||

| 6 | NC | 3.92 | 1.08 | 0.286 | 0.225 | 0.368 | 0.367 | 0.208 | 0.472 | |||||

| 7 | IST | 3.89 | 0.98 | 0.264 | 0.421 | 0.242 | 0.236 | 0.319 | 0.369 | 0.818 | ||||

| 8 | PN | 4.26 | 1.16 | 0.312 | 0.421 | 0.211 | 0.361 | 0.449 | 0.336 | 0.325 | 0.885 | |||

| 9 | AT | 4.12 | 1.26 | 0.198 | 0.430 | 0.396 | 0.267 | 0.203 | 0.295 | 0.375 | 0.402 | 0.799 | ||

| 10 | PBC | 4.08 | 0.89 | 0.208 | 0.552 | 0.503 | 0.438 | 0.366 | 0.403 | 0.298 | 0.358 | 0.379 | 0.689 | |

| 11 | SN | 3.96 | 1.02 | 0.226 | 0.416 | 0.467 | 0.496 | 0.497 | 0.246 | 0.261 | 0.403 | 0.323 | 0.556 | 0.723 |

| 12 | IN | 4.28 | 0.98 | 0.488 | 0.622 | 0.622 | 0.524 | 0.562 | 0.622 | 0.466 | 0.444 | 0.622 | 0.425 | 0.524 |

| 13 | ITM | 4.22 | 0.88 | 0.742 | 0.802 | 0.742 | 0.426 | 0.664 | 0.642 | 0.562 | 0.624 | 0.421 | 0.624 | 0.642 |

| Fit Indices | Model Value | Acceptable Standard |

|---|---|---|

| 1002.89 | - | |

| /Df | 1.92 | <2 |

| GFI | 0.924 | >0.9 |

| AGFI | 0.946 | >0.9 |

| CFI | 0.961 | >0.9 |

| IFI | 0.944 | >0.9 |

| NFI | 0.928 | >0.9 |

| RMSEA | 0.074 | <0.08 |

| Path | Standardized Estimate | p-Value | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JS | → | AT | 0.722 | 0.012 | Support |

| JSE | → | AT | 0.658 | 0.004 | Support |

| POS | → | AT | 0.302 | 0.061 | Not Supported |

| AC | → | AT | 0.604 | 0.012 | Support |

| CC | → | AT | 0.403 | 0.027 | Not Supported |

| NC | → | AT | 0.698 | 0.001 | Support |

| IST | → | AT | 0.716 | 0.002 | Support |

| PN | → | AT | 0.662 | 0.009 | Support |

| AT | → | IN | 0.546 | 0.009 | Support |

| PBC | → | IN | 0.724 | 0.001 | Support |

| SN | → | IN | 0.702 | 0.002 | Support |

| IN | → | ITM | 0.802 | 0.002 | Support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Safa, N.S.; Abroshan, H. The Effect of Organizational Factors on the Mitigation of Information Security Insider Threats. Information 2025, 16, 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070538

Safa NS, Abroshan H. The Effect of Organizational Factors on the Mitigation of Information Security Insider Threats. Information. 2025; 16(7):538. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070538

Chicago/Turabian StyleSafa, Nader Sohrabi, and Hossein Abroshan. 2025. "The Effect of Organizational Factors on the Mitigation of Information Security Insider Threats" Information 16, no. 7: 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070538

APA StyleSafa, N. S., & Abroshan, H. (2025). The Effect of Organizational Factors on the Mitigation of Information Security Insider Threats. Information, 16(7), 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070538