AI-Integrated Scaffolding to Enhance Agency and Creativity in K-12 English Language Learners: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.1.1. Sociocultural Theory and Collaborative Writing

1.1.2. Cognitive Theory and Writing Development

1.1.3. Integrating Sociocultural and Cognitive Perspectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Population: Research focusing on K-12 students and/or teachers in the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) context. For this review, EFL refers to students learning English in countries where English is not the dominant language.

- Focus on AI Integration: Studies examining AI tools specifically designed for writing instruction, such as Natural Language Generation (NLG) tools, Automated Essay Scoring (AES), paraphrasing tools, and AI-driven feedback systems.

- Outcome Relevance: Studies addressing cognitive engagement, creativity, scaffolding, student autonomy, or teacher perspectives on AI use in writing.

- Publication Date: Only studies published between 2018 and 2024 were included to ensure relevance to recent advancements in AI technology.

- Language: Only studies published in English to ensure consistency in analysis.

2.2. Search Strategy

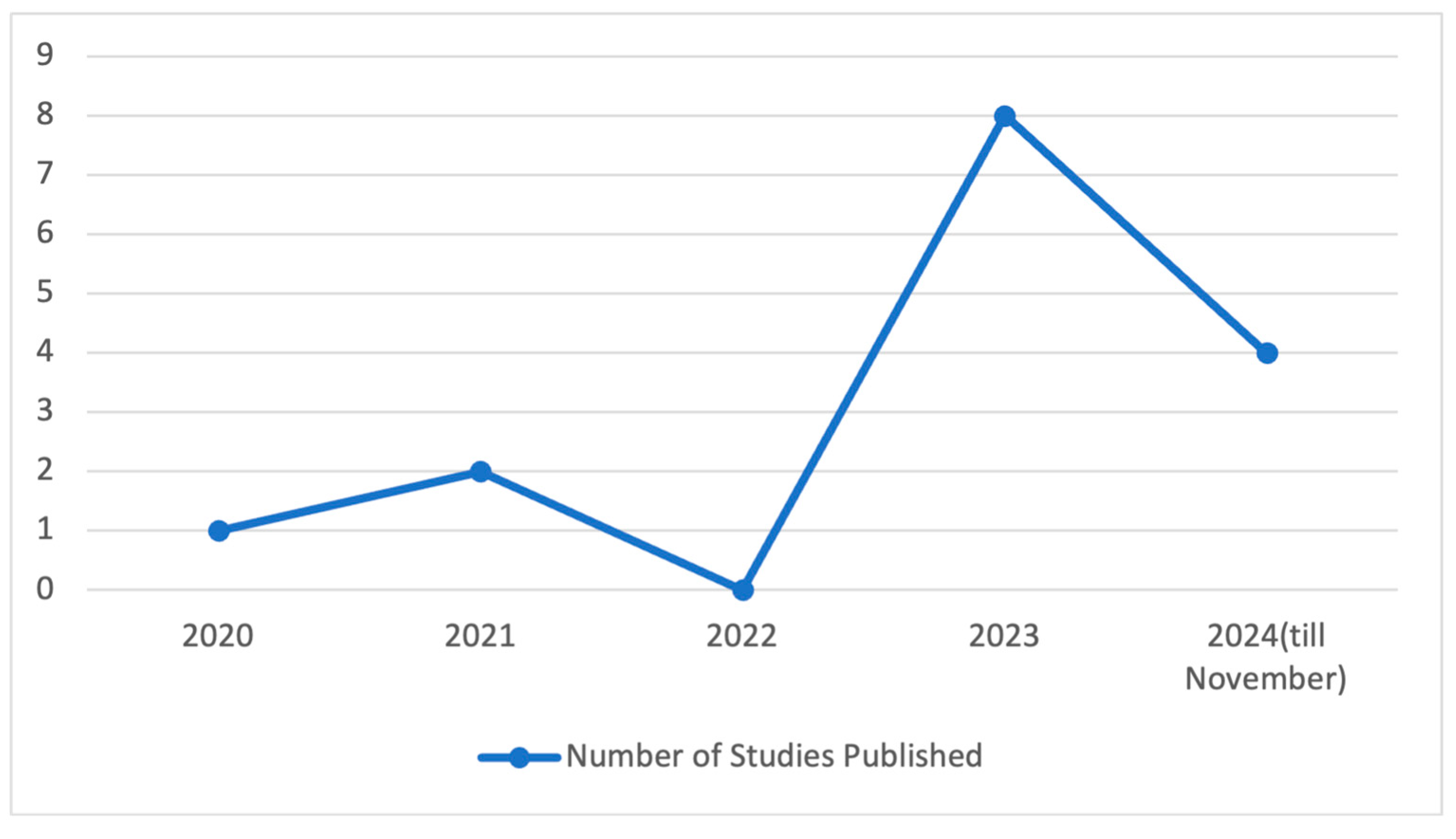

2.3. PRISMA Flow Diagram

2.4. Coding of Studies

- Study Metadata: Includes authorship, publication year, and setting to contextualize generalizability.

- AI Technologies Implemented: Captures the type, function, and interaction mode of AI tools used in writing instruction.

- Sample: Describes participant characteristics such as age, educational level, and language background to support subgroup analysis.

- Scaffolding Strategies/Design: Identifies how AI tools were embedded instructionally—e.g., feedback design, prompting structure, dialog models, or teacher mediation.

- Writing Activities/Outcomes: Summarizes the writing tasks and assessments used, indicating whether they targeted academic writing, narrative development, or revision.

- Key Findings on Creativity and Agency: Synthesizes outcome patterns linked to learner autonomy, ideation, self-regulation, and student-led decision making.

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. AI Scaffolding Approaches in EFL Writing

3.1.1. Cognitive Support Tools

3.1.2. Creative Support Systems

3.1.3. Language Enhancement Tools

3.2. Influence of AI Tools on Student Agency in EFL Writing

3.2.1. Autonomy in Writing Decisions

3.2.2. Self-Regulated Learning Behaviors

3.2.3. Control over Writing Process

3.2.4. Voice and Identity Expression

3.3. Influence of AI Tools on Student Creativity in EFL Writing

3.3.1. AI-Enhanced Ideation and Brainstorming

3.3.2. Novel Language Combinations

3.3.3. Genre Exploration and Development

3.3.4. Support for Creative Risk Taking

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis of Key Findings and Implications

4.1.1. Complementary Relationship Between Cognitive Support and Creative Development

4.1.2. Dynamic Balance Between AI Scaffolding and Student Autonomy

4.1.3. Alignment Between Theory and Practice

4.2. Pedagogical Implications

4.2.1. Teacher Mediation and Scaffolding Strategies

4.2.2. Balancing AI Support with Student Agency

4.2.3. Differentiated Implementation Approaches

4.2.4. Creating Supportive Learning Environments

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

4.3.1. Methodological Limitations

4.3.2. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoang, H.; Boers, F. Gauging the association of EFL learners’ writing proficiency and their use of metaphorical language. System 2018, 74, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ren, R. Language barriers and social-emotional learning (SEL) in Australian higher education: Addressing challenges for Chinese international students. Int. J. New Dev. Educ. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrot, J.S. Integrating technology into ESL/EFL writing through Grammarly. RELC J. 2022, 53, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alammar, A.; Amin, E.A.-R. EFL students’ perception of using AI paraphrasing tools in English language research projects. Arab World Engl. J. 2023, 14, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki; Widiati, U.; Rusdin, D.; Indrawati, D.; Indrawati, I. The impact of AI writing tools on the content and organization of students’ writing: EFL teachers’ perspective. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 2023, 10, 2236469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, D.J.; Susanto, H.; Yeung, C.H.; Guo, K.; Fung, A.K.Y. Exploring AI-generated text in student writing: How does AI help? Lang. Learn. Technol. 2024, 28, 183–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Song, Y. Enhancing academic writing skills and motivation: Assessing the efficacy of ChatGPT in AI-assisted language learning for EFL students. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1260843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E.; Ross, A.S.; Tan, C.; Ji, Y.; Smith, N.A. Creative writing with a machine in the loop: Case studies on slogans and stories. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, Tokyo, Japan, 7–11 March 2018; pp. 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, W.; Warschauer, M. AI-writing tools in education: If you can’t beat them, join them. J. China Comput.-Assist. Lang. Learn. 2023, 3, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Kim, N.J.; Heidari, A. Learner experience in artificial intelligence-scaffolded argumentation. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 1301–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Martínez, I.M.; Flores-Bueno, D.; Gómez-Puente, S.M.; Vite-León, V.O. AI in higher education: A systematic literature review. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1391485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.; Khosravi, H.; De Laat, M.; Bergdahl, N.; Negrea, V.; Oxley, E.; Pham, P.; Chong, S.W.; Siemens, G. A meta systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education: A call for increased ethics, collaboration, and rigour. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.-C.; Hwang, G.-H.; Tu, Y.-F.; Yang, K.-H. Roles and research trends of artificial intelligence in higher education: A systematic review of the top 50 most-cited articles. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 38, 22–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zheldibayeva, R. The adaptation and validation of the global competence scale among educational psychology students. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 2023, 11, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlTwijri, L.; Alghizzi, T.M. Investigating the integration of artificial intelligence in English as foreign language classes for enhancing learners’ affective factors: A systematic review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Cole, M., Jolm-Steiner, V., Scribner, S., Souberman, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, B. Apprenticeship in Thinking: Cognitive Development in Social Context; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Englert, C.S.; Raphael, T.E.; Anderson, L.M.; Anthony, H.M.; Stevens, D.D. Making strategies and self-talk visible: Writing instruction in regular and special education classrooms. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1991, 28, 337–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, A.M. Human-AI collaborative writing: Sharing the rhetorical task load. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (ProComm), Limerick, Ireland, 17–20 July 2022; pp. 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.A.; Nagy, W.E. Teaching Word Meanings, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, A.; Davis, L.; Ippolito, D.; Reif, E.; Yuan, A. Wordcraft: A human-AI collaborative editor for story writing. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.07430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, L.; Hayes, J.R. A cognitive process theory of writing. Coll. Compos. Commun. 1981, 32, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereiter, C.; Scardamalia, M. The Psychology of Written Composition; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gero, K.; Calderwood, A.; Li, C.; Chilton, L. A design space for writing support tools using a cognitive process model of writing. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Intelligent and Interactive Writing Assistants (In2Writing 2022), Dublin, Ireland, 26 May 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.; Chaudhary, K.; Hussein, S. A digital literacy model to narrow the digital literacy skills gap. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proske, A.; Narciss, S. Supporting prewriting activities in academic writing by computer-based scaffolds. In Beyond Knowledge: The Legacy of Competence; Zumbach, J., Schwartz, N., Seufert, T., Kester, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. AI-based writing tools: Empowering students to achieve writing success. Adv. Educ. Technol. Psychol. 2024, 8, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaidarova, S.; Bodaubekov, A.; Zhussipbek, T.; Gaipov, D.; Balta, N. Leveraging AI to enhance writing skills of senior TFL students in Kazakhstan: A case study using “Write & Improve”. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2025, 17, ep548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawanti, S.; Zubaydulloevna, K.M. AI chatbot-based learning: Alleviating students’ anxiety in English writing classroom. Bull. Soc. Inform. Theory Appl. 2023, 7, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, J.-C.; Chang, J.S. Enhancing EFL reading and writing through AI-powered tools: Design, implementation, and evaluation of an online course. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 32, 4934–4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, R.; Mustapha, R. Students’ perception on the use of digital mind map to stimulate creativity and critical thinking in ESL writing course. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 7596–7606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Maeng, U. Perceptions of high school students on AI chatbots use in English learning: Benefits, concerns, and ethical consideration. J. Pan-Pac. Assoc. Appl. Linguist. 2023, 27, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranalli, J. L2 student engagement with automated feedback on writing: Potential for learning and issues of trust. J. Second Lang. Writ. 2021, 52, 100816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, S.; Andayani, A.; Winarni, R.; Sumarwati, S. Utilization of artificial intelligence technology in an academic writing class: How do Indonesian students perceive? Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2023, 15, ep450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, D.J.; Wang, Y.; Susanto, H.; Guo, K. Understanding English as a foreign language students’ idea generation strategies for creative writing with natural language generation tools. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2023, 61, 1464–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Almusharraf, N.; Abdellatif, M.S.; Abbasova, M.Y. Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: Enhancing Learning Systems and Transforming Educational Paradigms. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. (iJIM) 2024, 18, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. AI and Education: Guidance for Policy-Makers; 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000376709 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Hattie, J.; Timperley, H. The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W.; Bialik, M.; Fadel, C. Artificial Intelligence in Education: Promises and Implications for Teaching and Learning; Center for Curriculum Redesign: Jamaica Plain, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Study (Author and Year) | AI Technologies Implemented | Sample | Scaffolding Strategies/ Design | Writing Activities/ Outcome | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agaidarova et al. (2025) [29] | Write & Improve platform | 134 senior-year high school students in Kazakhstan | Provides students with structured writing assignments, initial training on the Write & Improve platform, and immediate automated feedback to support their writing development in an online learning environment; also includes clear guidelines, assessment criteria aligned with IELTS standards, and the use of tools like Grammarly to ensure academic integrity | Using the Write & Improve platform to provide automated feedback on students’ weekly writing assignments, accompanied with traditional teacher feedback | AI feedback was equally effective as teacher feedback in improving writing proficiency, but did not enhance creativity or agency. Tool functioned as a corrective mechanism rather than a scaffold for student ownership or divergent thinking. |

| Alammar and Amin (2023) [4] | QuillBot, Grammarly, Ginger, SpinnerCeif | 25 high school students in Saudi Arabia | Students were trained to use automated paraphrasing tools for several stages of writing academic papers: outlining, drafting, proofreading, and editing | Students submitted writing outcome reviewed and edited with AI tools at each stage for data analysis | Over-reliance on AI limited original content generation, constraining the development of creative agency. |

| Coenen et al. (2021) [21] | Wordcraft editor: open-ended dialog AI system Meena | 8 middle school students in China | Uses a dialog model to enable flexible, task-specific interactions via conversation and then applies few-shot learning to adapt the model to each interaction type without retraining, and also embeds the AI capabilities into a familiar text editor UI for seamless human–AI collaboration during story writing | Students completed informal, self-directed creative writing with interactive AI assistance tool | High creative engagement and agency were observed as students shaped narrative direction through iterative prompting. |

| Hawanti and Zubaydulloevna (2023) [30] | ChatGPT | 73 high school students in Indonesia | 15 min per session to interact with ChatGPT to receive instant feedback, grammar correction, idea generation, and writing support, while maintaining structured teacher feedback and peer review sessions | Students were given academic writing assignments on selected topics like Purwokerto City, student organizations, early marriage, etc. | Limited evidence of enhanced creativity or student-led direction |

| Hsiao and Chang (2023) [31] | Custom AI-powered writing tool: Linggle Write, Linggle Read, and Linggle Search | 43 high school students in Taiwan | Teachers demonstrated how to use the AI-powered tools, and facilitated structured discussions to help students interpret AI feedback and apply it during writing and revision tasks | Students practiced using Linggle Write, Read, and Search in real-world tasks, wrote 100-word reflective paragraphs about their experiences, converted them into slides, and gave 2 min presentations. | While revision accuracy improved, creativity was bounded by template-like output and limited student control over feedback integration. |

| Karim and Mustapha (2020) [32] | Digital mind mapping software | 32 high school students in Malaysia | Instructor gives step-by-step instruction on mind mapping techniques and students try writing using it | Students were provided with AI software (iMindMap) to help them brainstorm and organize ideas before moving to later stages of writing | While creativity was scaffolded structurally, agency remained instructor-directed. AI played a minimal interactive role. |

| Kim et al. (2022) [10] | Custom-built chatbot on Chatfuel platform (Facebook messenger chatbot) | 69 11th grade students in South Korea | Three-stage graduated corrective recast approach delivered through an AI chatbot, moving from implicit feedback (repetition and clarification requests) to semi-explicit feedback (elicitation with prompts) to explicit feedback (direct recasts with correct forms) | Students completed Elicited Writing Tasks by constructing English caused-motion sentences based on picture and word cues | Students showed improvement in grammatical precision but limited autonomy. No meaningful development in creative composition or self-directed exploration. |

| Lee and Maeng (2023) [33] | ChatGPT | 30 first-year high school students in South Korea | Gives initial training on using AI chatbots, then gives structured writing assignments and surveys to gauge students’ perceptions of the benefits, concerns, and ethical considerations of utilizing chatbots for English learning | Students independently completed routine homework assignment writing | Some expressed increased independence in editing, but overall writing performance remained the same. |

| Marzuki et al. (2023) [5] | Grammarly; Quillbot; ChatGPT; Wordtune | 38 high school students in Indonesia | Allows students to obtain real-time feedback, grammar corrections, vocabulary suggestions, and writing assistance, while providing teacher guidance on appropriate tool usage and monitoring students’ dependence levels on these tools | Students can freely choose from a range of English writing tasks, such as assignments, projects, or work-related writing | Some students showed increased lexical diversity and confidence, but inconsistent agency. Concerns over AI dependency suggested mixed effects on self-directed development. |

| Ranalli (2021) [34] | Grammarly Premium | 6 high school students in China | Adopt multi-level scaffolding approach that combined technical training with hands-on practice: first teaching students how to code and customize their AI writing tools, then providing instruction on prompting techniques, text evaluation, and integration of AI-generated content into their writing | Student submitted an essay or written assignment that they had previously written for a course, including EFL writing course essays, essay test responses (e.g., history class), blog posts (e.g., for a design course), etc. | Results showed high engagement, increased agency in tool use, and flexible integration of AI-generated text, contributing to both linguistic creativity and learner autonomy. |

| Song and Song (2023) [7] | ChatGPT | 50 12th grade students in China | Three-step learning cycle where teachers first provided structured templates and guidance (Cornell notes, writing/slide templates), then allowed students to practice using AI tools in authentic contexts, and finally transitioned to student-centered presentations—creating a “learning loop” that gradually built learner autonomy through the progressive reduction in support. | Students completed the IELTS writing test | Students gained confidence in using ChatGPT for IELTS tasks. Evidence of growing ownership and self-direction, though creativity limited by the assessment format. |

| Utami et al. (2023) [35] | Write & Improve and AI Kaku, Eskritor, Grammarly, Plot Generator, Poem Generator, Speech-to-Text, Text-to-Speech, Smodin | 58 high school students in Indonesia | Teachers present and simulate how to use the tools, after which students worked in small groups to explore and apply the tools’ features like idea generation, introduction writing, and text expansion to help them with the writing tasks. | Students worked in groups of 2–4 to complete academic/scientific papers, progressing through the stages of planning, drafting, revising, and editing | Collaborative use promoted shared agency and some novel language generation, indicating a modest impact on both dimensions. |

| Woo et al. (2023) [36] | Four custom NLG tools developed on Hugging Face platform: Next Sentence Generator; Next Word Generator; Next Paragraph Generator 1; Next Paragraph Generator 2 | 4 secondary school students in Hong Kong, China | Provides students access to various NLG tools in voluntary creative writing workshops, where students can freely experiment with prompting the AI tools with their own text to generate new ideas, then they evaluate and selectively incorporate the AI-generated words and sentences into their stories. | Each student wrote an original English short story (maximum 500 words) using both their own words and AI-generated text, created through prompting custom-built Natural Language Generation (NLG) tools. | A high creative output and the self-guided integration of AI-generated text showed strong gains in both agency and creative expression. |

| Woo et al. (2024) [6] | Custom AI-NLG tools using Hugging Face language models | 23 secondary school students in Hong Kong, China | Two-workshop approach where students first learned technical skills for creating and customizing AI writing tools, followed by practical instruction on writing strategies including prompting techniques, text evaluation, and the integration of AI-generated content into their stories. | Students completed creative short story writing | Students exercised significant agency in deciding when and how to use AI output, enabling deep engagement with their own voice. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, M.; Wilson, J. AI-Integrated Scaffolding to Enhance Agency and Creativity in K-12 English Language Learners: A Systematic Review. Information 2025, 16, 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070519

Li M, Wilson J. AI-Integrated Scaffolding to Enhance Agency and Creativity in K-12 English Language Learners: A Systematic Review. Information. 2025; 16(7):519. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070519

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Molly, and Joshua Wilson. 2025. "AI-Integrated Scaffolding to Enhance Agency and Creativity in K-12 English Language Learners: A Systematic Review" Information 16, no. 7: 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070519

APA StyleLi, M., & Wilson, J. (2025). AI-Integrated Scaffolding to Enhance Agency and Creativity in K-12 English Language Learners: A Systematic Review. Information, 16(7), 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16070519