Driving International Collaboration Beyond Boundaries Through Hackathons: A Comparative Analysis of Four Hackathon Setups

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The “INVITE” Project

The “Open Interactive Digital Ecosystem”

2.2. The Four Hackathon Setups

2.2.1. Hackathon 1 (Chania, Greece)

2.2.2. Hackathon 2 (Cartagena, Colombia)

2.2.3. Hackathon 3 (Porto Alegre, Brazil)

2.2.4. Hackathon 4 (International, DigiEduHack)

2.2.5. Hackathon Setup Comparison

2.3. Research Method

- What are the key advantages and challenges associated with each hackathon setup?

- What are participants’ perceptions and overall experience in each hackathon setup?

- What best practices can be identified for designing higher education hackathons?

2.4. Consent for Participation

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

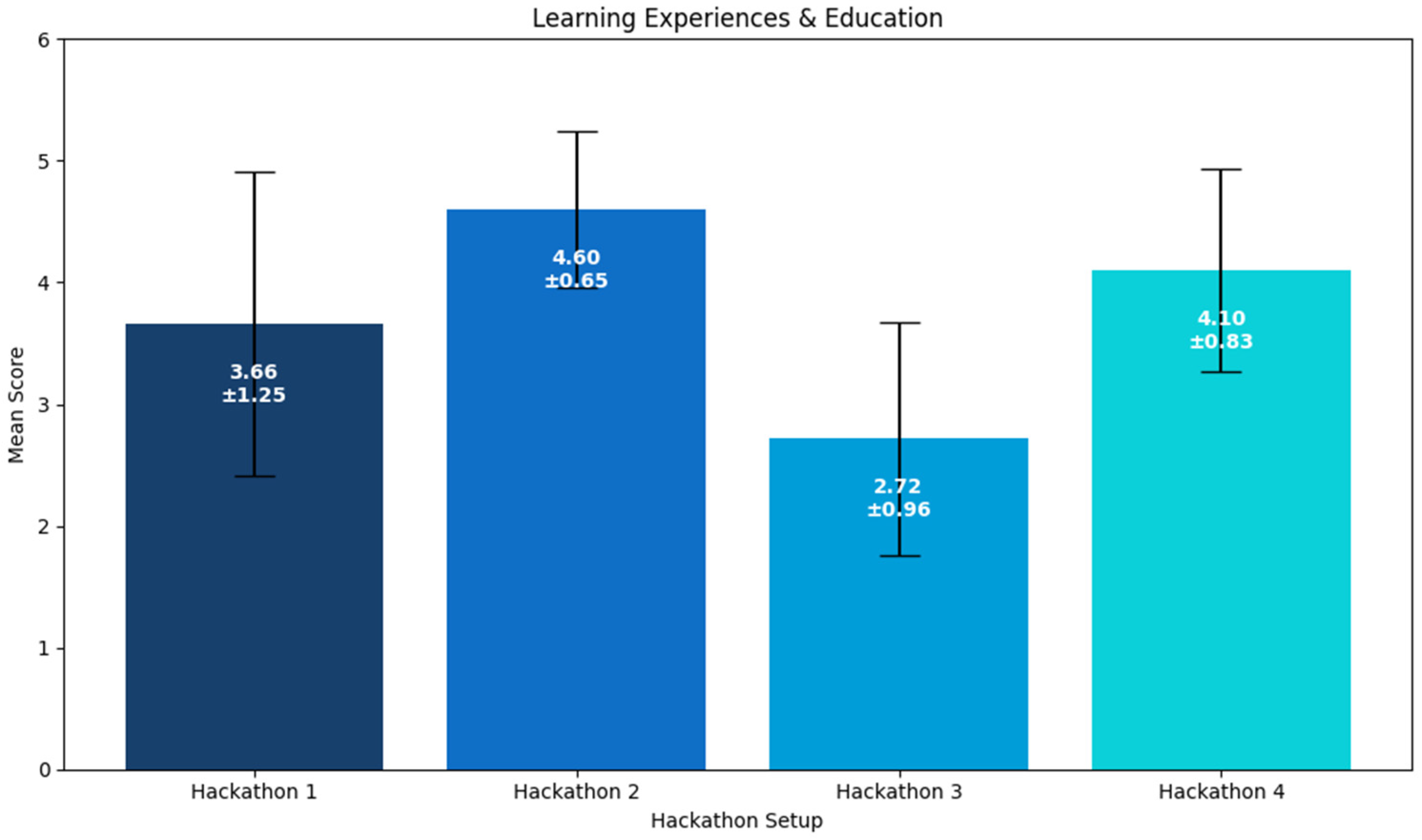

3.1.1. Learning Experiences and Education

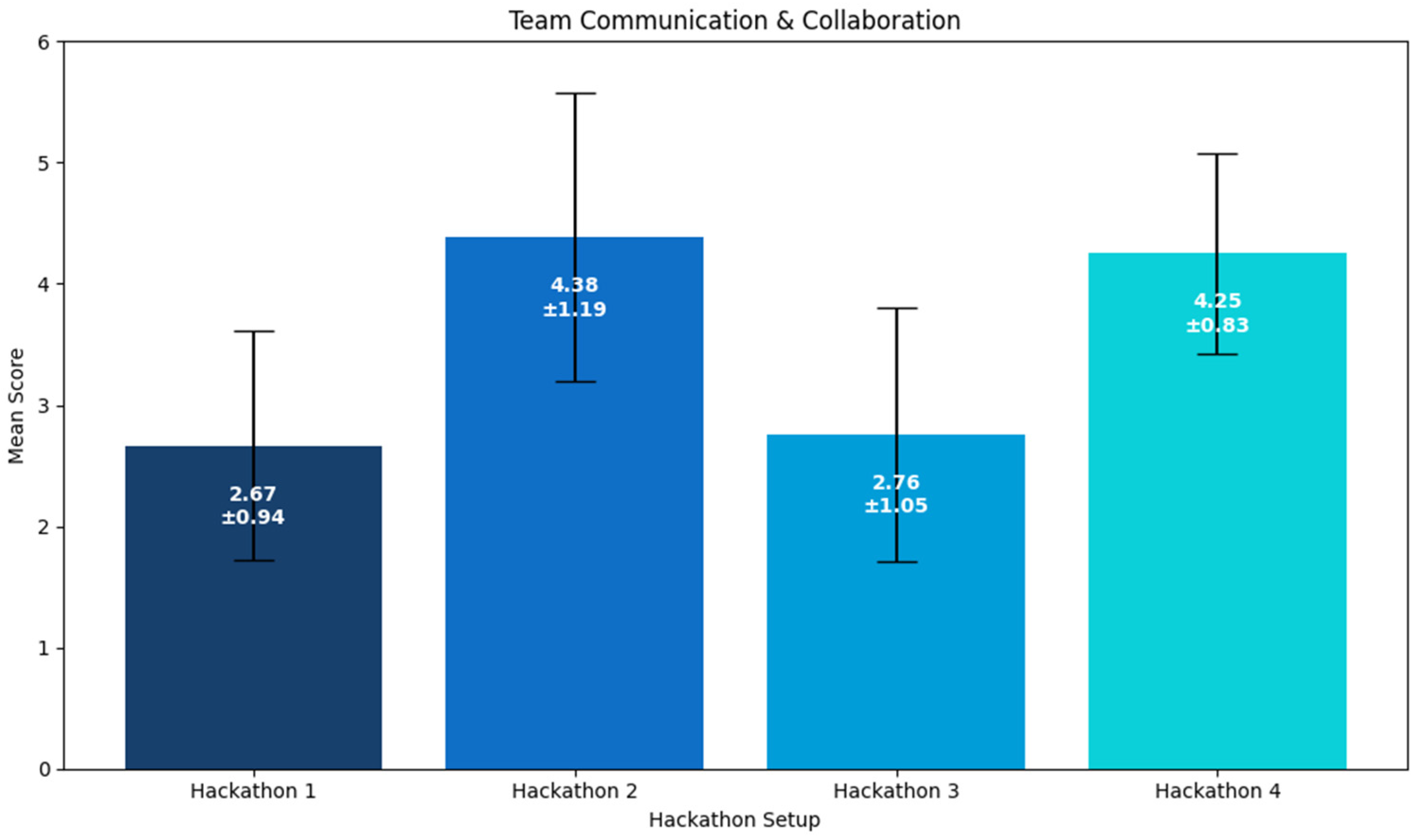

3.1.2. Team Communication and Collaboration

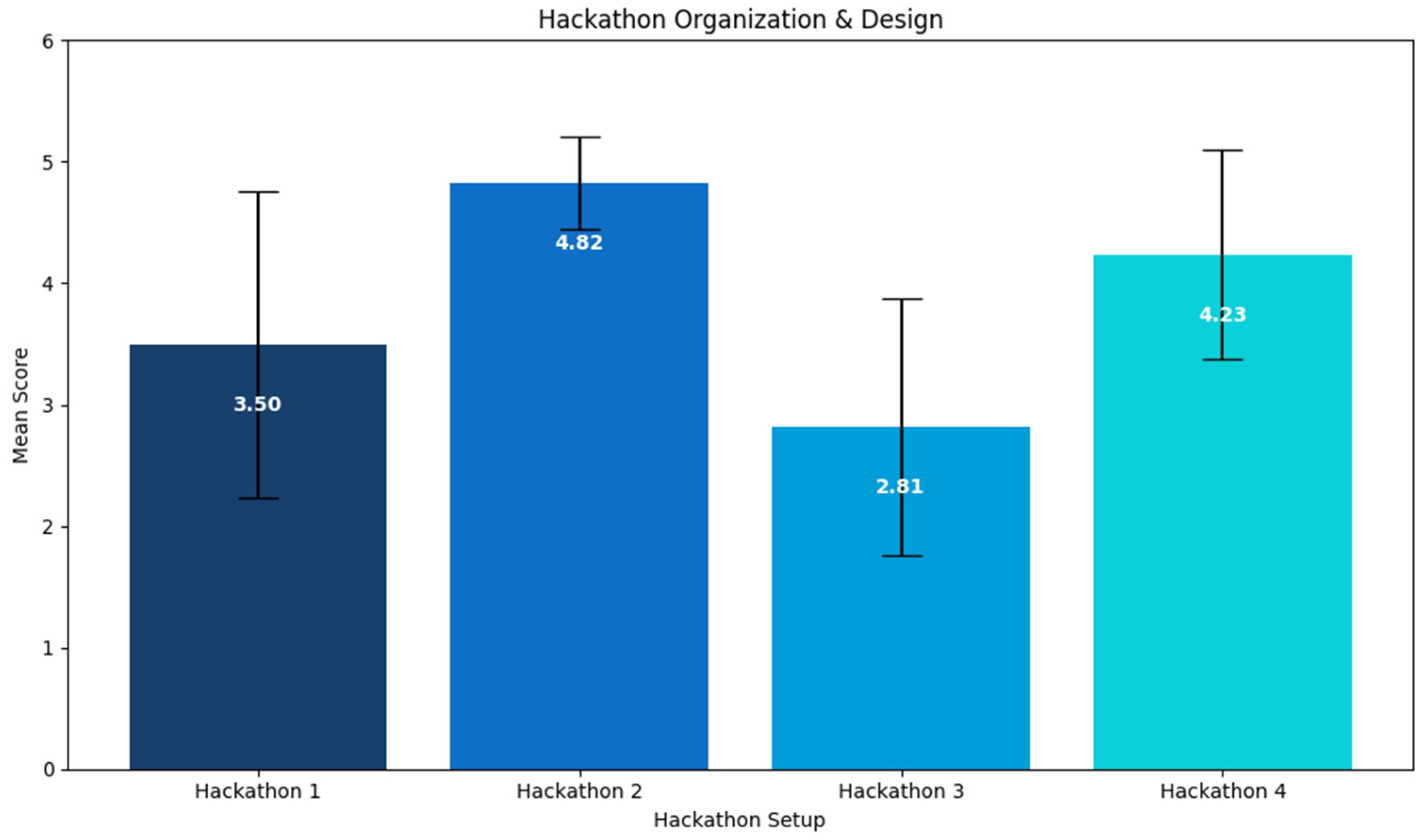

3.1.3. Hackathon Organization and Design

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Participants’ Feedback from Hackathon 1 (Chania, Greece)

3.2.2. Participants’ Feedback from Hackathon 2 (Cartagena, Colombia)

3.2.3. Participants’ Feedback from Hackathon 3 (Porto Alegre, Brazil)

3.2.4. Participants’ Feedback from Hackathon 4 (International, DigiEduHack)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADDIE | Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate |

| BIP | Blended Intensive Programme |

| DigiEduHack | Digital Education Hackathon |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SL | Service Learning |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

Appendix A

| Hackathon Event | Question(s) |

|---|---|

| Hackathon 1— Chania, Greece | -Was the available online material sufficient? |

| Hackathon 2— Cartagena, Colombia | -Do you consider that you achieved the learning objectives proposed at the beginning of the program? -Was the content relevant and useful to your academic training? |

| Hackathon 3— Porto Alegre, Brazil | -Did you achieve the objectives you wanted, and which were proposed in the MIP? -The activities offered at Marathon 2024 contributed to the development of my project -The topic addressed at the “Resilient Porto Alegre” International Meeting of the People was relevant and connected with my values, contributing to my education |

| Hackathon 4— International, DigiEduHack | -Was the available online material sufficient? |

| Hackathon Event | Question(s) |

|---|---|

| Hackathon 1— Chania, Greece | -Did you find the team formation procedure adequate? |

| Hackathon 2— Cartagena, Colombia | -Did you feel like you had enough opportunities to interact with your teammates virtually? |

| Hackathon 3— Porto Alegre, Brazil | -The Marathon provided me with an interdisciplinary experience, as it was possible to have contact with other areas of knowledge |

| Hackathon 4— International, DigiEduHack | -Did you find the team formation procedure adequate? |

| Hackathon Event | Question(s) |

|---|---|

| Hackathon 1— Chania, Greece | -Were the hackathon objectives clear? -Were the evaluation criteria clear? |

| Hackathon 2— Cartagena, Colombia | -How would you rate this experience overall? |

| Hackathon 3— Porto Alegre, Brazil | -In terms of the general organization, the event was… |

| Hackathon 4— International, DigiEduHack | -Were you satisfied with the hackathon experience? -Were you satisfied with the hackathon mentorship? -Judging criteria were clear? |

References

- Falk, J.; Nolte, A.; Huppenkothen, D.; Weinzierl, M.; Gama, K.; Spikol, D.; Tollerud, E.; Hong, N.P.C.; Knäpper, I.; Hayden, L.B. The Future of Hackathon Research and Practice. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 133406–133425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miličević, A.; Despotović-Zrakić, M.; Stojanović, D.; Suvajžić, M.; Labus, A. Academic performance indicators for the hackathon learning approach—The case of the blockchain hackathon. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyetade, K.; Zuva, T.; Harmse, A. Educational benefits of hackathon: A systematic literature review. World J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 14, 1668–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aalst, M.; Pfennig, T.; Chirove, F.; Ronoh, M.; Matuszyńska, A. Hackathons as essential tools in an interdisciplinary biological training—Report from trainings for sub-saharan students. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotaquirá-Gutiérrez, R.; Beltran, L.M.; Garzon Ruiz, J.P. Hackathons as experiential learning platforms for engineering design skills. Cogent Educ. 2024, 12, 2442187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina Angarita, M.A.; Nolte, A. What Do We Know About Hackathon Outcomes and How to Support Them? A Systematic Literature Review. In Collaboration Technologies and Social Computing; CollabTech 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Nolte, A., Alvarez, C., Hishiyama, R., Chounta, I.A., Rodríguez-Triana, M., Inoue, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 12324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyetade, K.; Zuva, T.; Harmse, A. Evaluation of the impact of hackathons in education. Cogent Educ. 2024, 11, 2392420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulten, C.; Chounta, I.A. How do we learn in and from Hackathons? A systematic literature review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 20103–20134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk Olesen, J.; Kannabiran, G.; Hansen, N.B. What Do Hackathons Do? Understanding Participation in Hackathons Through Program Theory Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama Japan, 8–13 May 2021; pp. 1–16, Article 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barana, A.; Chatzea, V.E.; Henao, K.; Hildebrandt, A.M.; Marchisio Conte, M.; Samoilovich, D.; Triantafyllidis, G.; Vidakis, N. Designing an online training module to develop virtual and blended international modalities in higher education. In Proceedings of the International Conferences Mobile Learning 2025 and Educational Technologies 2025, Madeira Island, Portugal, 1–3 March 2025; pp. 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Trainer, E.H.; Kalyanasundaram, A.; Chaihirunkarn, C.; Herbsleb, J.D. How to Hackathon: Socio-technical Tradeoffs in Brief, Intensive Collocation. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing—CSCW’16, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2016; pp. 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, B.; Amir, A.; Waxman, R.; Maaravi, Y. Hack your organizational innovation: Literature review and integrative model for running hackathons. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolte, A.; Pe-Than, E.P.P.; Affia, A.O.; Chaihirunkarn, C.; Filippova, A.; Kalyanasundaram, A.; Angarita, M.A.M.; Trainer, E.; Herbsleb, J.D. How to organize a hackathon—A planning kit. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.08025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.S.; Murray, F.E.; Davies, E.L. An investigation of the features facilitating effective collaboration between public health experts and data scientists at a hackathon. Public Health 2019, 173, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, F.; Sweeney, S.; Bruce, F.; Baxter, S. The use of the “Hackathon” in design education: An opportunistic exploration. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education (E&PDE16), Design Education: Collaboration and Cross-Disciplinarity, Aalborg, Denmark, 8–9 September 2016; pp. 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Rosell, B.; Kumar, S.; Shepherd, J. Unleashing innovation through internal hackathons. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Innovations in Technology Conference, Warwick, RI, USA, 16 May 2014; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Day, K.; Humphrey, G.; Cockcroft, S. How do the design features of health hackathons contribute to participatory medicine? Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2017, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaravi, Y. Running a research marathon. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2017, 55, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uys, W.F. Hackathons as a formal teaching approach in information systems capstone courses. In Proceedings of the ICT Education: 48th Annual Conference of the Southern African Computer Lecturers’ Association, SACLA 2019, Northern Drakensberg, South Africa, 15–17 July 2019; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. Revised Selected Papers 48. pp. 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kohne, A.; Wehmeier, V. Hackathons. In Springer eBooks; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.; Bender, K.; DeChants, J. Beyond the Classroom: The Impact of a University-Based Civic Hackathon Addressing Homelessness. J. Soc. Work. Educ. 2019, 55, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobham, D.; Gowen, C.; Jacques, K.; Laurel, J.; Ringham, S. From appfest to entrepreneurs: Using a hackathon event to seed a university student-led enterprise. In Proceedings of the INTED2017 Proceedings, IATED, Valencia, Spain, 6–8 March 2017; pp. 522–529. [Google Scholar]

- Bugarszki, Z.; Lepik, K.L.; Kangro, K.; Medar, M.; Amor, K.; Medar, M.; Saia, K. Guideline for Social Hackathon Events; Tallinn University: Tallinn, Estonia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, S.; Presenza, A.; Petruzzelli, A.M. Boosting innovative business ideas through hackathons. The “Hack for Travel” case study. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, M.; Lockwood, K. Hackathons as Community-Based Learning: A Case Study. TechTrends 2016, 60, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarova, B.; Ledesma, E.; Luhan, G.; Cafey, S.; Giusti, C. Learning from collaborative integration: The hackathon as design charrette. In ECAADE 2015: Real Time-Extending the Reach of Computation, Vienna, Austria, 16–18 September 2015; Martens, B., Wurzer, G., Grasl, T., Lorenz, W.E., Schafranek, R., Eds.; Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe (eCAADe): Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- European Association of Service-Learning in Higher Education (EASLHE). Policy Brief: A European Framework for the Institutionalization of Service-Learning in Higher Education. 2021. Available online: https://www.eoslhe.eu/easlhe/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Resch, K.; Freudhofmayer, S.; Martínez-Usarralde, M.J. A promising methodology. Assessing the pedagogical value of hackathons. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parviainen, P.; Kääriäinen, J.; Tihinen, M.; Teppola, S. Tackling the digitalization challenge: How to benefit from digitalization in practice. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2017, 5, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hackathon 1 | Hackathon 2 | Hackathon 3 | Hackathon 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Chania, Greece | International and onsite in Cartagena, Colombia | International and onsite in Porto Alegre, Brazil | International, DigiEduHack |

| Hackathon title | Gamified STEM Course design on Green Agenda | Building sustainable cities in Latin America | Innovation marathon 2024: Porto Alegre, a resilient city | Green Campus Hackathon: building digital solutions for SDGs and Green Agenda integration in university life |

| Dates | 27–31 May 2024 | 11 June–18 July 2024 | 31 October–8 November 2024 | 13–14 November 2024 |

| Duration | 5 days | Online: 8 sessions Onsite: 4 days | 1-day training 5 days hackathon | 2 days (2 × 12 h slots) |

| Event organization | Hosted during the 11th International Week and 3rd ATHENA International Week | In alignment with local hackathons organized by Universidad Tecnológica de Bolivar | In alignment with the local marathon in Porto Alegre | Hosted during the DigiEduHack 2024 registered in 2024 European sustainable development week |

| Event format | Onsite | Blended (onsite and online for all students) | Hybrid (onsite for local students and online for international students) | Online |

| Group formation | Teams or solo self-formulation | Teams organized according to 3 criteria: thematic self-selection, interdisciplinarity, and internationality | Teams organized according to 3 criteria: thematic self-selection, interdisciplinarity, and internationality | Teams Self/host formulation |

| Participants profile | 10 participants from European countries, over 30 years old, mainly researchers and professors | 50 bachelor students (38 onsite and 12 online) from 7 Latin American countries formed 7 teams. Average age 22 years old, over 15 academic disciplines | 88 participants (62 local students and 26 international) from 8 Latin American countries formed 16 teams. Average age 23 years old, over 15 academic disciplines | 66 international participants (from bachelor students to professors), over 18 years old, forming 15 teams |

| Hackathon sessions | Pre-Event: - Registration - Training Event: - Analyze, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate (ADDIE) methodology design - Submit solutions Post-Event: - Project evaluation - Winner’s announcement | Day 1: - Enlistment - Context - Conferences, inspiration rounds Day 2: - Ideation of solutions - Prototyping Day 3: - Business model - Validation with real users Day 4: - Pitch presentations - Awards | Online Training: - Meet the teams - Methodology (how Moodle platform works) Event: - Kick-off - Conferences, inspiration rounds - Definitions of ideas - Making decisions - Prototyping - Mentoring validations - Validation - Presentations - Awards | Pre-Event: - Registration - Training - Team formation - Kick-off session - Team building - Meet the mentors Event: - Welcome session - Project ideation - Welcome back session - Project finalization - Pitch preparation - Video submission Post-Event: - Projects evaluation - Award nomination |

| Dedicated hackathon platform | INVITE digital platform | - | - | INVITE digital platform |

| Tools used for the hackathon | ADDIE methodology | Canva Zoom Ideation materials INVITE course resources for BIP | Canva Zoom Moodle INVITE course resources for BIP | DigiEduHack Discord |

| Supportive material provided | Green Agenda ADDIE methodology Gamification INVITE digital platform guide | Canva presentation Onsite teaching materials Resources for BIP | Moodle materials INVITE course resources for BIP | Green Agenda/SDGs Solution canvases Pitch deck tips INVITE digital platform guide |

| Final solutions | PowerPoint presentations | Prototypes—web pages/synchronous onsite pitches | Prototypes/synchronous hybrid pitches | Pitch deck video presentations |

| Mentors | 5 locals | 3 internationals 1 local | 3 internationals 12 locals | 12 internationals |

| Jurors | 4 locals | 5 locals | 4 locals | 3 internationals |

| Evaluation | 100% by jurors | 100% by jurors | 100% by jurors | 70% by jurors 30% by participants |

| Rewards | Collection of local traditional products | Diplomas prizes for the 3 first places | 1st place: mentoring for developing prototype and participation in track lab/service learning 2nd Place: tecnopuc garage development program | 1st place: EUR 250 gift card prize and 3 mentorship sessions with the INVITE consortium 2nd place: EUR 150 gift card prize |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barana, A.; Chatzea, V.E.; Henao, K.; Hildebrandt, A.M.; Logothetis, I.; Marchisio Conte, M.; Papadakis, A.; Rueda, A.; Samoilovich, D.; Triantafyllidis, G.; et al. Driving International Collaboration Beyond Boundaries Through Hackathons: A Comparative Analysis of Four Hackathon Setups. Information 2025, 16, 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16060488

Barana A, Chatzea VE, Henao K, Hildebrandt AM, Logothetis I, Marchisio Conte M, Papadakis A, Rueda A, Samoilovich D, Triantafyllidis G, et al. Driving International Collaboration Beyond Boundaries Through Hackathons: A Comparative Analysis of Four Hackathon Setups. Information. 2025; 16(6):488. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16060488

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarana, Alice, Vasiliki Eirini Chatzea, Kelly Henao, Ania Maria Hildebrandt, Ilias Logothetis, Marina Marchisio Conte, Alexandros Papadakis, Alberto Rueda, Daniel Samoilovich, Georgios Triantafyllidis, and et al. 2025. "Driving International Collaboration Beyond Boundaries Through Hackathons: A Comparative Analysis of Four Hackathon Setups" Information 16, no. 6: 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16060488

APA StyleBarana, A., Chatzea, V. E., Henao, K., Hildebrandt, A. M., Logothetis, I., Marchisio Conte, M., Papadakis, A., Rueda, A., Samoilovich, D., Triantafyllidis, G., & Vidakis, N. (2025). Driving International Collaboration Beyond Boundaries Through Hackathons: A Comparative Analysis of Four Hackathon Setups. Information, 16(6), 488. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16060488