Deglobalization Trends and Communication Variables: A Multifaceted Analysis from 2009 to 2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Setting the Stage: From Global Financial Crisis to Deglobalization

1.2. Research Problem and Significance

1.3. Scope

1.4. Research Questions

- RQ1: Does increasing trade protectionism correlate with heightened deglobalization discourse and shifts in language usage (i.e., language entropy)?

- RQ2: Are higher levels of trade protectionism associated with intensified political polarization and more frequent public protests?

- RQ3: Does rising trade protectionism predict enhanced digital authoritarianism (e.g., more censorship and internet shutdowns)?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptualizing Deglobalization

2.2. Trade Protectionism as an Indicator of Deglobalization

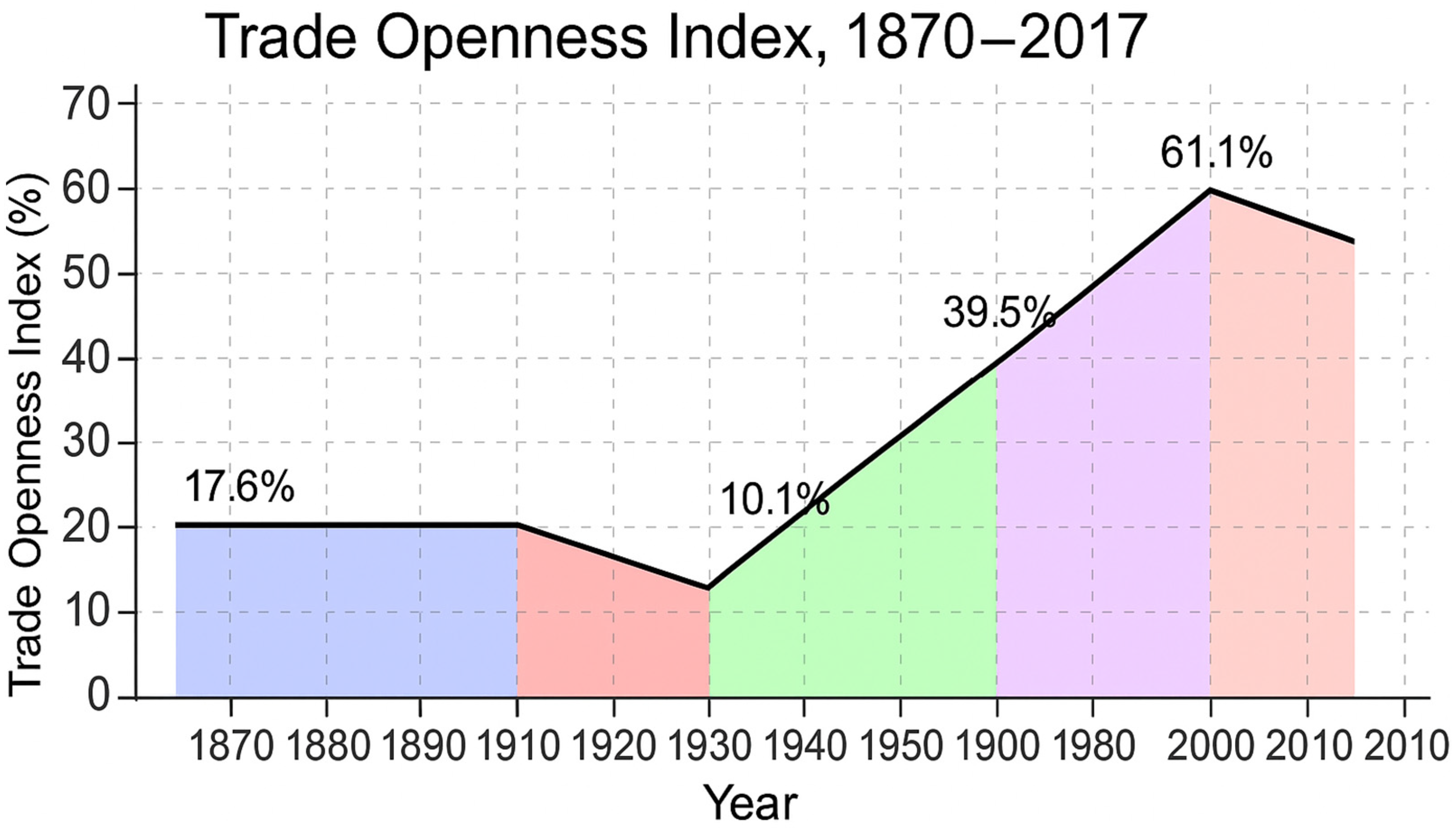

Historical Patterns of Globalization and Deglobalization

2.3. Communication Outcomes of Deglobalization

2.3.1. Deglobalization Discourse

2.3.2. Language Entropy

2.3.3. Political Polarization

2.3.4. Protests

2.3.5. Digital Authoritarianism

2.4. Theoretical Underpinnings

2.4.1. World Systems Theory

2.4.2. Optimal Information Theory

2.4.3. Theorizing the Effects of Trade Protectionism on Social Unrest and Polarization

2.4.4. Theoretical Explanations for Trade Restriction Effects on Digital Authoritarianism

2.4.5. Deglobalization and Language

3. Hypotheses

- Rationale: As nations adopt tariffs and other protectionist measures, public and media discourse shifts to concepts such as “deglobalization”, highlighting the move away from globally integrated markets.

- Rationale: Constraints on cross-border exchange reduce reliance on a common global language, potentially allowing local or regional languages to proliferate. Higher protectionism may thus correspond to more linguistically diverse communication environments.

- Rationale: Domestic politics may harden into “for or against” stances on globalization, triggering or exacerbating ideological extremes. We expect periods of high protectionism to coincide with intensified polarization discourse.

- Rationale: Protectionist policies can disrupt economies, engendering public dissatisfaction. This may lead to more frequent protests or collective actions as citizens express grievances.

- Rationale: Governments anticipating unrest (partly due to economic strains from protectionism) might expand internet censorship and surveillance to pre-empt dissent. Thus, higher protectionism may be associated with more frequent mentions of digital repression tactics.

4. Methodology

4.1. Data and Sampling

4.1.1. Time Frame and Justification

4.1.2. Key Data Sources

- Global Trade Alert (GTA): This is an independent database that tracks worldwide trade interventions. From GTA, we extracted two metrics: (a) Inceptions, the count of newly introduced restrictive measures each year (e.g., new tariffs enacted that year), and (b) Protections in Force, the total stock of active protectionist measures in effect each year (cumulative count up to that year). These serve as quantitative proxies for the extent of trade protectionism (and by extension, economic deglobalization) at a global level. Units: Both are simple counts of measures; Inceptions reset each year, whereas Protections in Force accumulate over time.

- Facebook (CrowdTangle): We used CrowdTangle, a tool that indexes public posts from Facebook pages and groups. Through keyword queries, we gathered two types of information from Facebook posts: (a) language usage data for computing language entropy (by searching broadly for posts containing the term “communication” and retrieving the language each post is written in), and (b) mention counts for specific terms like “political polarization”, “protest”, “digital authoritarianism”, etc. (by querying posts containing those phrases). Units: For language, we obtained counts of posts per language per year. For mentions, we obtained annual frequencies of posts containing each target term. These are raw counts, which we later log-transformed for analysis.

- Google Search Data: Using Google’s search engine, we logged the approximate number of results (hits) each year for keywords such as “deglobalization”, “political polarization”, “digital authoritarianism”, “protest”, etc. This provides a broad measure of how often these terms appear on the web (across websites, not just news or social media). Units: The raw numbers represent Google’s reported hit counts, which are rough estimates of indexed pages containing the term. We collected these data for each year (e.g., by using time-bound search filters when possible or by recording annual values if available from Google Trends or similar sources). Because Google’s reporting can be inconsistent, we treat these as indicative volume measures and apply log transformations for analysis.

- Nexis Uni (News Articles): Nexis Uni aggregates content from major newspapers worldwide, including dedicated tracking of key sources such as The New York Times. From Nexis Uni, we retrieved (a) the annual count of news articles that mention our keywords (“deglobalization”, “political polarization”, etc.), and (b) full-text corpora of those articles for qualitative context (though our quantitative analysis primarily uses the counts). We specifically included English-language major newspapers across different regions to capture mainstream media discourse. Units: The counts represent the number of articles per year that contain the term across a defined set of “major newspaper” sources. In some cases, we separated The New York Times (NYT) as a benchmark U.S. outlet from other global sources, known as “Major Newspapers”, to determine whether trends were global or driven by specific media.

- Global Internet Activity (Google Page Count): As a control variable, we obtained an estimate of the total number of webpages indexed by Google each year, serving as a proxy for overall internet content growth. This serves as a covariate to account for the fact that mentions of anything tend to increase over time simply because more content is put online each year. Units: We used global estimates from Google statements and independent research sources. In our dataset, this is represented as the annual Google Pages (total) count, which we log-transformed. For example, if Google indexed ~50 billion pages in 2010 and ~200 billion in 2020 (hypothetical figures), this growth could inflate all search-based counts; controlling for it helps isolate more specific trends.

4.1.3. Justifying Mentions as Proxies for Actual Behaviors

- Mentions as Reflective Signals of Behavior

- News media and digital platforms respond to observable changes in society, covering them in real time;

- Publics engage with issues that are salient or experienced directly, such as attending a protest, reacting to new tariffs, or navigating border restrictions;

- Empirical studies confirm strong correlations between digital discourse and on-the-ground events (e.g., correlations between Google Trends data and consumer behavior or between Twitter posts and protest turnout).

- 2.

- Mentions as Constitutive Forces in Social Dynamics

- Framing theory shows how issues that are discussed shape how they are understood and acted upon.

- Discourse analysis highlights that repeated mention of particular narratives (e.g., “deglobalization”, “national sovereignty”, and “foreign threat”) can create shared mental models that influence perception and guide behavior.

- Mentions in digital networks contribute to the viral spread of ideas, norm activation, and even mobilization, such as through hashtags that help coordinate protest activity or signal ideological alignment.

- 3.

- Strategic Utility and Theoretical Fit

- The Optimal Information Theory lens views increases in communicative activity as responses to rising uncertainty and as mechanisms of system adaptation.

- The discursive institutionalist perspective treats language, narrative, and symbolism as central to institutional change and political action.

4.2. Variables

- Trade Protectionism: Inceptions (annual count of new protectionist measures) and Protections in Force (cumulative count of active measures). These two indicators capture different dynamics: Inceptions highlight yearly surges or dips in protectionism, while Protections in Force reflect the accumulated trade barriers at a given time. In our tables, we sometimes denote Inceptions as PROTECT (short for protectionism in that year) and Protections in Force as PROTECTIONS (plural, indicating total ongoing measures). Both are measured as raw counts (continuous, potentially large numbers), which we later log-transform due to high skew.

- Deglobalization Discourse: To quantify the prominence of “deglobalization” in public conversation, we aggregated mention volumes from multiple sources: Google hits, Nexis Uni articles, and Facebook posts referencing “deglobalization”. Because these measures are on different scales and exhibit highly collinear trends, we employed principal component analysis (PCA) to combine them into a single composite index. Specifically, we obtained the annual counts from DEGLOBAL_GOOGLE, DEGLOBAL_NEWS (major newspapers), DEGLOBAL_NYT (specifically, the NYT), and DEGLOBAL_FACEBOOK (FB posts), each of which was log-transformed. PCA yielded a first principal component that explained the majority of variance across these four indicators (we report it as DEGLOBAL_FACTOR). This factor (a continuous variable, with a mean of zero by construction) represents the overall intensity of deglobalization discourse per year. Units: It is unitless (standardized score), but higher values indicate years with collectively higher “deglobalization” mentions across all sources. (For reference, PCA factor loadings were all > 0.85 on this component, indicating strong contributions from each source.)

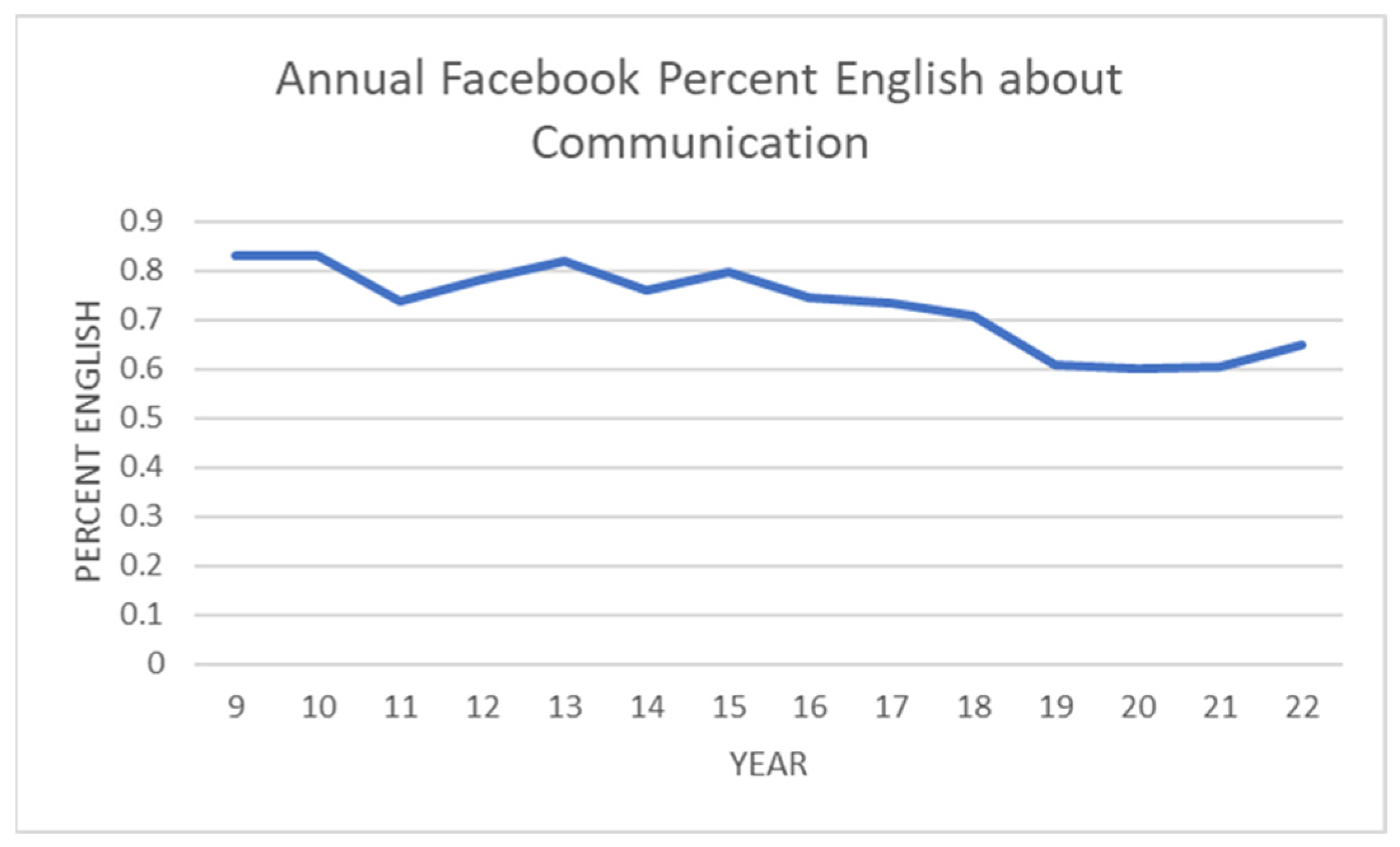

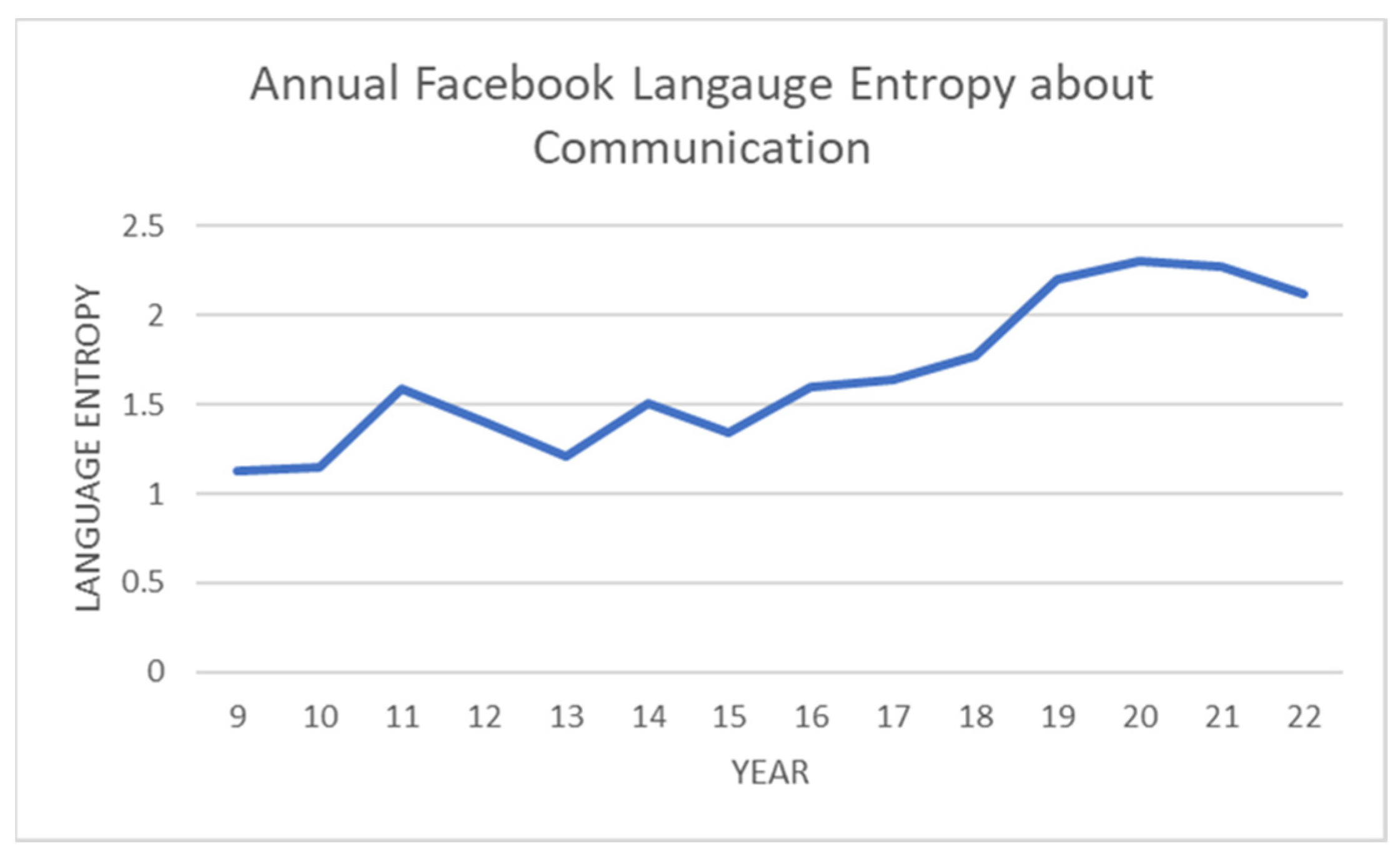

- Language Entropy: To measure linguistic diversity, we computed the Shannon entropy (H) of language use in Facebook posts about “communication”. Using the language detected for each post (via FastText’s language ID for 157 possible languages), we calculated the following Equation (1):where pi is the proportion of posts in language i for a given year, and N is the number of distinct languages observed that year (bounded by 157) (units: bits (since log base 2)). Higher ENTROPY means a more even spread among languages (no single language dominates), whereas lower entropy means one or few languages account for most content. For example, if, in 2009, English accounted for 80% of posts and other languages made up the rest, entropy might be low (~1 bit); if, by 2020, English was 60% and many others share the remainder, entropy rises (~2 bits or more), indicating a more balanced distribution. This variable captures the concept of shifts in English versus local language usage—an indirect proxy for cultural deglobalization.

- Political Polarization: We measured this by the frequency of the term “political polarization” (and its close variants) in our sources. We summed logged counts from Google, Nexis Uni (news), and CrowdTangle (Facebook) for mentions of “political polarization” per year. We treat POLARIZATION as a composite count (in practice, because these sources correlated strongly, one could also use any single source; we opted to sum and then log) (units: effectively, the log of the count of mentions per year). This reflects the prominence of polarization in discourse, which we interpret as a proxy for the actual intensity of polarization in society, acknowledging its imperfection.

- Protests: Similar to polarization, we tracked the frequency of “protest” or “protests” in Google results, news articles, and Facebook posts annually. PROTESTS is our aggregated, logged count of protest-related mentions (units: log count per year of mentions). This highlights the salience of protests in public communication, which often aligns with actual protest events; spikes in media discussion of protests typically coincide with real protest waves, even though not every mention corresponds to an actual protest.

- Digital Authoritarianism: We developed an index for digital repression narratives, utilizing terms such as “digital authoritarianism”, “internet shutdown”, “online censorship”, and “social media ban”. Specifically, we counted mentions of a set of related keywords across Google, news, and Facebook. These counts were combined (summed after log transformation for each term) to form an overall DIGITAL_AUTH variable (units: log count of mentions per year (across sources, multiple terms)). We included multiple terms to capture various facets of the concept; for instance, some articles may not use the term “digital authoritarianism” but instead report that “the government blocked Facebook”. Our composite aims to reflect the general level of discourse about governments controlling the internet or digital repression.

- Control—Global Content Growth: GOOGLE_PAGES is our control variable, representing the annual log of Google-indexed pages. By including this, we attempt to account for the secular growth of content and connectivity over time. Without this control, correlations among our variables might be inflated by the fact that all variables increased over 2009–2023 (e.g., more trade measures, more internet content, and more mentions of any word, simply due to global growth). This variable has a mean of approximately 0 and a small variance after log transformation and normalization (since it was centered) and is used in partial correlation analyses.

4.3. Analytical Procedures

4.3.1. Log Transformations

4.3.2. Correlation and Assumption Checks

4.3.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4.3.4. Partial Correlations

4.3.5. Robustness and Exploratory Checks

- Year omissions: We omitted potential outlier years and recalculated correlations. Specifically, we excluded 2009 (the first year after the crisis, which may have had unstable data) and, separately, excluded 2020 (the year of COVID-19 onset, which saw unusual disruptions). In each case, we compared the correlation patterns with the full sample.

- Inceptions vs. Protections: We examined whether using Inceptions (new measures) vs. Protections in Force (ongoing measures) yields different strengths of association with outcomes. This addresses whether short-term spikes or cumulative pressure are more important.

- Alternate keywords: For the digital authoritarianism variable, we explored different combinations of terms (e.g., using only “internet shutdown” or only “censorship”) to determine if a particular term was driving the results. We found the trend to be robust across different terms; all showed upward movement and correlated with the rise in protectionism.

- Data transformations: We tested whether not logging the variables (or logging the trade measures) changed conclusions. Without logs, the correlations remained positive but were even more dominated by time trends (nearly all variables increased over time), yielding extremely high correlations (0.9+) across the board. That was not informative, so the logged results are preferred. Logging the trade measures also yielded similar qualitative findings (results were slightly strengthened for polarization when using logged protectionism; for consistency, we present the unlogged trade measure results in the main tables).

- Autocorrelation and time-lag exploration: Although 14 points are too few for serious time-series modeling, we performed a rudimentary check for autocorrelation. Year-to-year changes were not our primary focus, but all series exhibit strong autocorrelation, largely due to their trend. We considered first-differencing to see if year-over-year protectionism changes correlate with outcomes. Those correlations were weaker and often not significant, which is expected if effects are cumulative or if the signal-to-noise ratio in annual deltas is low. Thus, our main analysis focuses on the level values. Still, we acknowledge this limitation; more sophisticated time-series models (e.g., ARIMA or cross-correlation) would require longer series or more granular data (e.g., quarterly) to be effective.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

- Trade Protectionism: Inceptions ranged from about 1600 in 2009 to ~25,000 at their peak in the late 2010s (with an average of ~8000 per year if we calculated the mean of yearly introductions). There was a notable jump around 2016, paralleling events like the Brexit referendum and the U.S. presidential election, and then some fluctuation through 2023. Protections in Force rose consistently yearly, reflecting that most new measures remained in effect and accumulated. By the end of the period, there were over 25,000 active protectionist measures globally, up from just ~1600 in 2009, illustrating a significant shift toward trade restrictiveness.

- Deglobalization Discourse: Mentions of “deglobalization” were negligible in 2009–2010 (often fewer than 100 hits in mainstream media databases). Post-2015, the term’s usage increased exponentially, peaking around 2019–2020. This timing coincided with intense coverage of U.S.–China trade tensions and discussions of retreating globalization in policy circles. For instance, 2019 saw a surge in think-tank reports and news stories asking if globalization was in reverse. Our PCA-based factor captures this spike; notably, the 2019–2020 period has the highest factor scores (around 2–3 SDs above the mean).

- Language Entropy: In Figure 2, we track the percentage of English in Facebook “communication” posts, and in Figure 3, we track the entropy. English accounted for ~80% of such posts in 2009, but dropped to around 60% by 2020, indicating an increase in posts in other languages. Correspondingly, Shannon entropy rose from ~1.10 bits to ~2.20 bits over the period. An entropy of 1.1 bits suggests one language (English) heavily dominates with a few others making minor contributions; 2.2 bits suggests a more even mix (though still not uniform by any means; English was still the largest share, but smaller relative to before). This empirical trend supports the idea that global English dominance in online discourse slightly receded in the late 2010s, allowing more multilingual content, which is consistent with H2’s expectation under deglobalization.

- Political Polarization, Protests, and Digital Authoritarianism: All three showed marked increases in textual mentions starting in the mid-2010s, with prominent surges around 2016–2017 and again around 2019–2020. Key real-world referents include the 2016 U.S. election and Brexit (which amplified talk of polarization and also triggered protests in some places); the late 2010s rise in populist governments (some imposing digital controls and hence more talk of digital authoritarianism); and the 2019–2020 period which included global protest waves (e.g., climate strikes, Hong Kong protests, various protests in Latin America), plus the onset of COVID-19 (prompting both protests and emergency powers that sometimes curbed digital freedoms). According to our data, polarization discourse roughly doubled (in log terms) from the early 2010s to the late 2010s; protest mentions showed a similar jump. Digital authoritarianism-related terms were scarcely mentioned pre-2014 but were common in policy reports and news by 2020 (for example, the term “digital authoritarianism” gained currency around 2018, and many reports of internet shutdowns in 2019–2021 added to the count).

5.2. Correlations

5.3. Partial Correlations Controlling for Internet Growth

5.4. Robustness Checks

5.5. Summary of Hypothesis Tests (H1–H5)

Deglobalization Discourse (H1)

Language Entropy (H2)

Political Polarization (H3)

Protests (H4)

Digital Authoritarianism (H5)

6. Discussion

6.1. Linking Empirical Patterns to Theory

- World Systems Theory: We found that as global interconnectedness weakened (due to rising tariffs, etc.), internal complexities increased: local languages gained ground (resulting in higher entropy), political factions hardened (leading to polarization), and governments exercised greater control over online spaces (manifesting as digital authoritarianism). This resonates with Wallerstein’s idea that breaking down a global core–periphery structure leads to intensifying internal reconfigurations. For instance, the dominance of the core-country language (English) diminished slightly, consistent with a diffusion of power. The strong correlations support a WST-informed view that deglobalization has systemic effects domestically: as the “core” influence recedes, nations turn inward, which in our data meant more inward-facing behaviors and challenges.

- Optimal Information Theory (OIT): Danowski’s extension of OIT suggested an inverse relationship between external ties and internal network density. Our results show that higher protectionism (fewer external economic ties) is associated with more intense internal dynamics, whether new language patterns or conflictual discourse requiring crackdowns. The strong correlation of protectionism with language entropy, protests, and digital authoritarianism [62,63,64] aligns with the notion that when external variety is reduced, internal signals amplify to compensate. In essence, a country facing less external economic input may generate more internal complexity (not all positive, as indicated by polarization and unrest). This provides indirect empirical evidence in support of OIT at a societal level.

- Social Strain and Resource Mobilization: The high correlation between protectionism (Protections in Force) and protest references reinforces the idea that economic disruptions or shifts can mobilize discontented groups. This is consistent with resource mobilization theory’s [76] claim that grievances, paired with available resources (such as communication networks and organizations), result in social movement activity. Likewise, social strain theory predicts that sustained pressure (cumulative protectionism) yields cumulative strain, culminating in protests. Our data cannot prove the mechanism, but the temporal alignment is suggestive. It is plausible that tariffs and trade shocks contributed to conditions (e.g., rising prices and unemployment in certain sectors) that sparked protests, or at least that both stem from a broader context of discontent.

- Political/Cultural Backlash: We observed a rise in language entropy alongside the emergence of protectionism, which aligns with the notion that local identities reassert themselves as globalization recedes [14]. Cultural Backlash Theory posits that segments of society react against global or liberal norms by emphasizing traditional or regional identities. The use of local languages could be one such expression. Additionally, the correlation between protectionism, polarization, and digital authoritarianism can be seen as a double-edged backlash: one portion of society pushing nationalist policies (a backlash against globalism), which then triggers another backlash in the form of protests or opposition, prompting an authoritarian response from the state. It is a chain of reactions consistent with polarization, where two camps pull apart and conflict ensues.

6.2. Political and Social Implications

- Amplified Polarization: The correlation between protectionism and polarization discourse is evident in real-world examples. For instance, the U.S.’s “America First” trade policies and the UK’s Brexit (essentially, deglobalization moves) went hand in hand with highly polarized political climates. Our data suggest this is not coincidental; economic nationalism often comes packaged with narratives that split societies (globalist vs. patriot, etc.). This implication worries governance: countries could face more gridlock and less social cohesion if pursuing protectionist policies tends to deepen internal divides. Policymakers should be mindful that trade policy is not just a matter of technocratic economics; it has significant social ramifications.

- Rise in Protest Activity: History shows that sudden economic policy shifts (like sharp tariff increases) can trigger unrest, e.g., farmers protesting export bans and consumers protesting price hikes. Our data from the 2010s support this: as protectionism rose, so did protests in many parts of the world. Whether directly causal or due to underlying discontent, the association suggests that governments embracing protectionism may need to prepare for managing public dissent. For example, several countries that increased tariffs on fuel or food saw immediate street protests due to cost-of-living issues. Our findings align with this pattern. Thus, even policies intended to protect may have the paradoxical effect of inciting protest if they impose burdens on population segments.

- Digital Authoritarianism: One of the most striking findings is the high correlation between trade protectionism and references to digital control. This suggests a coupling of economic nationalism with information nationalism. A possible interpretation is that regimes that turn inward economically tend to tighten control over information, finding justification to maintain a cohesive narrative. For example, a government might censor online criticism of its protectionist policies or generally suppress dissent during economically tough times, which are often exacerbated by trade restrictions. The normative implication is significant: deglobalization may threaten digital rights and freedoms, as it could be accompanied by censorship and surveillance. Societies should be vigilant to ensure that “shielding the economy” is not used as a pretext to shield the public from information.

6.3. Relevance for Policymakers

- Policymakers should recognize the knock-on effects of protectionist economic decisions. Implementing a tariff to protect the domestic industry may not occur in a vacuum; it may alter domestic social dynamics and intensify political tensions. For instance, if protectionism leads to higher prices, this can become a political issue, polarizing public opinion and leading to protests. A government focusing on “economic sovereignty” might inadvertently fuel internal discord.

- A government that builds physical or regulatory trade barriers might also be more likely to erect “digital barriers”. Our analysis suggests a parallel: censorship or surveillance often accompanies shifts in nationalist policy. Therefore, advocates for free expression and internet freedom should pay attention to shifts in economic policy as potential early warning signs. Conversely, trade policymakers should consult with human rights advisors when advocating protectionist agendas, as such measures may have implications for civil liberty.

- Integrated Monitoring: This could be beneficial to monitor a dashboard of indicators: trade measures alongside social media sentiment, protest incidence, and internet freedom metrics. Such holistic monitoring might help anticipate crises. For example, suppose a country is ramping up trade barriers, and one sees simultaneous spikes in polarization on Twitter and protests being organized on Facebook. In that case, it may signal instability brewing that could escalate unless addressed.

- Communication Strategy: If a state chooses protectionist measures for legitimate reasons (say, to safeguard a critical sector), it should proactively communicate the rationale and address potential misconceptions to mitigate polarization. Transparency and inclusive dialogue can help prevent an “us vs. them” narrative from taking over. Without clear communication, people may fill the void with speculation or propaganda, worsening polarization.

6.4. Limitations and Future Directions

- Small Sample of Annual Observations: We have only 14 time points. This raises the risk of spurious or inflated correlations; even random trends could appear significant with so few data points. While using large textual corpora per point lends some substantive validity, statistically, the sample is underpowered. Any conclusions are tentative. Future research should extend the time frame (as more years pass or possibly look historically further back to see if data can be compiled) or increase granularity (e.g., quarterly data and country-level panels) to provide more robust tests.

- Reliance on Mentions as Proxies: Our measures for polarization, protest, and other phenomena are based on counts of mentions in media and online content, rather than direct measures of the phenomena themselves. This is an important caveat: increased talk of “protests” does not always mean more actual protests occurred; it could reflect media sensationalism or other factors. Similarly, a society can be polarized without explicitly using the term “polarization” in articles. We chose these proxies due to global data availability. However, they imperfectly represent reality. Triangulating with more direct indicators would strengthen the case. For example, future studies could incorporate actual protest event data (counts of protests by year from databases such as ACLED), survey-based polarization metrics, or observed measures of language use (such as the percentage of web content in English versus other languages). Using multiple measures can also help alleviate biases (e.g., media censorship may underreport protests, so combining this with social media counts helps, which we partially did).

- Causality and Endogeneity: Our design is correlational, and we explicitly acknowledge this. We cannot disentangle whether trade protectionism leads to social tensions or whether a broader underlying factor, such as a wave of populism, drives both protectionism and the social outcomes. Indeed, it is plausible that a rise in nationalist sentiment around 2015 caused both anti-globalization policies and more polarized, protest-prone societies. The relationships are likely bidirectional and complex. To address causation, future research could employ time-series techniques (e.g., Granger causality tests or vector autoregressive models) to determine if changes in one variable precede changes in another more clearly. Alternatively, examining country-specific cases or natural experiments (e.g., a country that suddenly raises tariffs due to a political event and observes whether its protest frequency changes compared to similar countries) could provide insight. Cross-lagged panel analyses with country-level data may reveal whether past protectionism predicts future polarization better than vice versa.

- Interdisciplinary Data Integration Issues: Combining data from economics, media studies, and computational linguistics presents significant challenges. Each comes with different biases and error structures. For instance, Google’s hit counts are notoriously imprecise and can vary by orders of magnitude based on unknown indexing quirks. Nexis Uni’s coverage of newspapers might be biased toward English-speaking outlets or certain types of outlets. Although large, Facebook data only cover public posts and may not be representative of the broader discourse (mostly in English or a subset of engaged users). Additionally, while novel, our language entropy measure depends on accurate language detection and the representativeness of “posts about communication” as a sample. Our interdisciplinary approach may thus suffer from comparability issues; we treated all data streams with equal weight, but perhaps they should not be. For example, an uptick in Google hits might not be as meaningful as the same percentage uptick in a curated news database. Future work could improve this by calibrating measures (e.g., validating Google counts against known values or focusing on more consistent data sources).

- Variable Definition Clarity: While we strived to define each variable, some ambiguity remains. For instance, what constitutes a “protectionist measure” in GTA could range from a tariff to a subsidy, and not all measures have an equal economic impact. Similarly, “digital authoritarianism” encompasses various actions (censorship and surveillance) that may have different social consequences. Future studies may break these down further, perhaps as a separate analysis for “internet shutdowns” versus “social media censorship” to determine if one correlates more closely with unrest than the other. Ensuring consistent variable symbols and understanding is crucial. In our tables, we used shorthand like ‘PROTECT’ and ‘PROTECTIONS’, which could confuse readers if unclear. We have clarified these terms in the text (e.g., PROTECT = new measures and PROTECTIONS = cumulative). However, further clarity or standardization (such as using Inceptions vs. Protections in Force labels) would be helpful, especially as this work spans disciplines where terminology can differ.

- Cross-Cultural Variation: Our analysis treated the world somewhat monolithically. These relationships likely vary by country or region. For example, a country with strong institutions might implement tariffs without experiencing significant polarization, whereas in a more volatile political system, even minor protectionist measures could spark substantial conflicts. Our global aggregate could be dominated by the patterns of a few large countries (e.g., the U.S., China, and India), where content volume is substantial. A future direction is to disaggregate and examine country-level data, if possible. Some of our metrics can be compiled by country, as Global Trade Alert reports measures per country. Additionally, news and social media can be filtered by country or language. A panel study with countries as units could reveal whether the correlations hold broadly or are driven by specific cases. It could also test for moderation: for example, perhaps the link between protectionism and protests is stronger in democracies, where people can protest, than in autocracies, where protests are suppressed.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Main Contributions

7.2. Policy Recommendations

- Consideration of Social Externalities: Policymakers deliberating tariffs or quotas should weigh broader ramifications. Economic protection may achieve certain goals, such as protecting jobs in a sector, but can also stoke domestic political tensions and inadvertently prompt authorities to curtail freedoms if unrest escalates. A cost–benefit analysis of a trade policy should include social costs, such as increased polarization or protests, which have economic impacts of their own (e.g., instability can deter investment).

- Multilateral Engagement: Our findings suggest that engaging with the international community may mitigate some negative domestic effects. If absolute economic nationalism tends to polarize the population, participating in selective cooperation forms could ease the “us vs. them” narrative. For instance, leaders can pair protectionist moves with diplomatic efforts in other areas to demonstrate a balanced approach. Discussing digital rights and openness in trade negotiations could help forestall a slide into digital authoritarianism. International bodies, such as the WTO or G20, could explicitly address the interplay between trade policy and social cohesion, encouraging members to adopt measures that minimize societal disruption.

- Fostering of Inclusive Communication Environments: Civil society and the media play a crucial role. In times of deglobalization, maintaining open channels of discourse is key. Efforts to promote media literacy and resist disinformation can help mitigate worsening polarization. Encouraging multilingual content and dialogue might turn the language entropy finding positive. Instead of seeing the decline of a lingua franca as a fracturing, it can be embraced as a form of cultural pluralism. Educational and cultural institutions might emphasize national languages in a way that unites rather than divides (e.g., bilingual education that values both English and local languages). At the same time, they should guard against extreme nationalist narratives. Social media platforms should be vigilant about how their algorithms might amplify polarization in a politically charged environment, building on research into the filter bubble phenomenon.

7.3. Closing Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Rodhan, N.R.; Stoudmann, G. Definitions of globalization: A comprehensive overview and a proposed definition. Program. Geopolit. Implic. Glob. Transnatl. Secur. 2006, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. Information Technology, Globalization and Social Development; UNRISD: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999; Volume 114. [Google Scholar]

- Narlikar, A. The World Trade Organization: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Shangquan, G. Economic Globalization: Trends, Risks and Risk Prevention; CDP Background Paper; Economic & Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, D.A. The Pandemic Adds Momentum to the Deglobalization Trend. Peterson INSTITUTE for International Economics. 2020. Available online: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/pandemic-adds-momentum-deglobalization-trend (accessed on 15 March 2004).

- Stiglitz, J.E. Globalization and Its Discontents Revisited: Anti-Globalization in the Era of Trump; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Evenett, S.J. What can be learned from crisis-era protectionism? An initial assessment. Bus. Politics 2009, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Li, P.; Lee, Y.R. Observations of deglobalization against globalization and impacts on global business. Int. Trade Politics Dev. 2020, 4, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobolt, S.B. The Brexit vote: A divided nation, a divided continent. J. Eur. Public Policy 2016, 23, 1259–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carothers, T.; O’Donohue, A. (Eds.) Democracies Divided: The Global Challenge of Political Polarization; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Polyakova, A.; Meserole, C. Exporting Digital Authoritarianism: The Russian and Chinese Models; Policy Brief, Democracy and Disorder Series; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Freedom House. Freedom on the Net 2022: Countering an Authoritarian Overhaul of the Internet; Freedom House: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Scholte, J.A. Globalization: A Critical Introduction, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik, D. The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, M.A. De-globalization: Theories, Predictions, and Opportunities for International Business Research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 1053–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Steger, M.B. A genealogy of globalization: The career of a concept. Globalizations 2014, 11, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B.; Voola, R.; Mir, R. Transformational resistance: Deglobalization and the ethical corporation. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 162, 793–807. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, G. Economic globalization? In A Globalizing World? Held, D., McGrew, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; pp. 85–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, I. The Modern World-System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2011; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, D.A. Welfare effects of British free trade: Debate and evidence from the 1840s. J. Political Econ. 1988, 96, 1142–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripsman, N.M. Globalization, deglobalization and great power politics. Int. Aff. 2021, 97, 1317–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bolle, M.; Zettelmeyer, J. Measuring the Rise of Economic Nationalism; Working Papers 19-15; Peterson Institute for International Economics: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hovden, E.; Keene, E. (Eds.) The Globalization of Liberalism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Amadi, L. Globalization and the changing liberal international order: A review of the literature. Res. Glob. 2020, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornprobst, M.; Paul, T.V. Globalization, deglobalization and the liberal international order. Int. Aff. 2021, 97, 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, E.D.; Rudra, N. Embedded liberalism in the digital era. Int. Organ. 2021, 75, 558–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupnik, J. Orbán’s vision for Europe. IPS J. 2024. Available online: https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/european-integration/orbans-vision-for-europe-7627/ (accessed on 5 July 2024).

- Itakura, K. Evaluating the impact of the US–China trade war. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 2020, 15, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauber, J.; Laborde Debucquet, D.; Martin, W.; Vos, R. COVID-19: Trade Restrictions Are the Worst Possible Response to Safeguard Food Security. In COVID-19 and Global Food Security; Swinnen, J., McDermott, J., Eds.; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Chapter 14; pp. 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, H. China and global internet governance: Toward an alternative analytical framework. Chin. J. Commun. 2016, 9, 304–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wei, F. Comparative Analysis of Digital Economy-Driven Innovation Development in China: An International Perspective. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracane, M.F.; Kren, J.; van der Marel, E. The cost of data protectionism. J. Int. Econ. Law 2018, 21, 769–789. [Google Scholar]

- James, H. Deglobalization: The rise of disembedded unilateralism. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2018, 10, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTO. Overview of Developments in the International Trading Environment: Annual Report by the Director-General; WTO: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hahm, S.D.; Heo, U. History and territorial disputes, domestic politics, and international relations: An analysis of the relationship among South Korea, China, and Japan. Korea Obs. 2019, 50, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, E.; Kendall-Taylor, A.; Wright, J. Digital Repression in Autocracies; V-Dem Institute Users Working Paper Series 2020:27; Varieties of Democracy Institute: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2020; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kubin, E.; von Sikorski, C. The role of (social) media in political polarization: A systematic review. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2021, 45, 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.W.; Park, S.J. The Filter Bubble Generated by Artificial Intelligence Algorithms and the Network Dynamics of Collective Polarization on YouTube: The Case of South Korea. Asian J. Commun. 2024, 34, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, L.; Molina, C. Facebook Causes Protests; Documento CEDE No. 41; Universidad de los Andes, CEDE: Bogotá, Colombia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Freedom House. Freedom on the Net 2018: The Rise of Digital Authoritarianism; Freedom House: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, D. English as a Global Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Danowski, J.A.; van Klyton, A.; Peng, T.Q.W.; Ma, S.; Nkakleu, R.; Biboum, A.D. Information and communications technology development, interorganizational networks, and public sector corruption in Africa. Qual. Quant. 2023, 57, 3285–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, L.; Gersbach, H. The great divide: Drivers of polarization in the US public. EPJ Data Sci. 2020, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyengar, S.; Lelkes, Y.; Levendusky, M.; Malhotra, N.; Westwood, S.J. The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2019, 22, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, I.; Pettigrew, T.F. Relative deprivation theory: An overview and conceptual critique. Br. J. Social. Psychol. 1984, 23, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, K.R. Strain theory. In Readings in Deviant Behavior; Clinard, M., Ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, I.; Burke, S.; Berrada, M.; Cortés, H. World Protests 2006–2013; Initiative for Policy Dialogue and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung New York Working Paper; SSRN: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013; pp. 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, K.H. Rumors That Move People to Action: A Case of the 2019 Hong Kong Protests. J. Contemp. East. Asia 2022, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Danowski, J.A. Bitcoin price associations with political polarization, digital authoritarianism, trade protectionism, deglobalization, and language entropy. ROSA J. 2025, 2, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniger, J. The Control Revolution: Technological and Economic Origins of the Information Society; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, F. Theories of the Information Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, G.A. A longitudinal analysis of the international telecommunication network, 1978–1996. Am. Behav. Sci. 2001, 44, 1638–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, G.A. Recent developments in the global telecommunication network. In Proceedings of the 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; pp. 4435–4444. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, G.A.; Chon, B.S.; Rosen, D. The structure of the Internet flows in cyberspace. NETCOM Réseaux Commun. Et Territ. Netw. Commun. Stud. 2001, 15, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danowski, J.A. Arab countries’ global telephone traffic networks and civil society discourse. In Civic Discourse and Digital Age Communications in the Middle East; Amin, H., Gher, L., Eds.; Ablex Publishing: Westport, CT, USA, 2000; pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.H.; Danowski, J.A. Making a global community on the net–global village or global metropolis?: A network analysis of Usenet newsgroups. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2002, 7, JCMC735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutschmann, E. Mapping the Transnational World: How We Move and Communicate Across Borders, and Why it Matters; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, G.A.; Lee, M.; Jiang, K.; Park, H.W. The flow of international students from a macro perspective: A network analysis. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2016, 46, 533–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.I.; Barnett, G.A.; Lim, Y.S. The structure of international music flows using network analysis. New Media Soc. 2010, 12, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Bertalanffy, L. The history and status of general systems theory. Acad. Manag. J. 1972, 15, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, W.R. An Introduction to Cybernetics; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Danowski, J.A. Environmental Uncertainty, Group Communication Structure, and Stress. Master’s Thesis, Department of Communication, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Danowski, J.A. An Information Processing Model of Organizations: A Focus on Environmental Uncertainty and Communication Network Structuring; Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association: New Orleans, LA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Danowski, J.A. An Information Theory of Communication Functions. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Communication, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Danowski, J.A. Group attitude uniformity and connectivity of organizational communication networks for production, innovation, and maintenance content. Human Commun. Res. 1980, 6, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danowski, J.A. An emerging macro-level theory of organizational communication: Organizations as virtual reality management systems. In Emerging Perspectives in Organizational Communication; Thayer, L., Barnett, G., Eds.; Ablex: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 141–174. [Google Scholar]

- Danowski, J.A.; Edison-Swift, P. Crisis effects on intraorganizational computer-based communication. Commun. Res. 1985, 12, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in Organizations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; Volume 3, pp. 1–231. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. Communication Power; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coser, L.A. Social conflict and the theory of social change. Br. J. Sociol. 1957, 8, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, W.J. A theory of role strain. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnworth, M.; Leiber, M.J. Strain theory revisited: Economic goals, educational means, and delinquency. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1989, 54, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuchler, S.M. Understanding Social Movements: Theories from the Classical Era to the Present; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, J.D.; Zald, M.N. Resource mobilization and social movements: A partial theory. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 82, 1212–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J.C. Resource mobilization theory and the study of social movements. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1983, 9, 527–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriesi, H. The political opportunity structure of new social movements: Its impact on their mobilization. WZB Discuss. Pap. 1991, 91, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D.S.; Staggenborg, S. Movements, countermovements, and the structure of political opportunity. Am. J. Sociol. 1996, 101, 1628–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, D.A.; Benford, R.D. Master frames and cycles of protest. In Frontiers in Social Movement Theory; Morris, A.D., McClurg Mueller, C., Eds.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1992; pp. 133–155. [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta, M. Protesting in ‘hard times’: Evidence from a comparative analysis of Europe, 2000–2014. Curr. Sociol. 2016, 64, 736–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, C. The Globalization Backlash; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, S. The backlash against globalization. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2021, 24, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, N.; Qureshi, S.; Nadeem, M. Globalization: A threat to intra-state social cohesion. Pak. Vision. 2015, 16, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, T. In the aftermath of globalization: Antiglobalizing and deglobalizing forms of subjectivity. Theory Psychol. 2023, 33, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, L.; Fetterolf, J.; Connaughton, A. Diversity and Division in Advanced Economies; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Bäck, H.; Carroll, R. Polarization and gridlock in parliamentary regimes. Legis. Sch. 2018, 3, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington, M.J.; Rudolph, T.J. Why Washington Won’t Work: Polarization, Political Trust, and the Governing Crisis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Scheufele, D.A.; Tewksbury, D. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. J. Commun. 2007, 57, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi-Sánchez, J.L. Deglobalization and public diplomacy. Int. J. Commun. 2021, 15, 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Danowski, J.A.; Yan, B.; Riopelle, K. Cable news channels’ partisan ideology and market share growth as predictors of social distancing sentiment during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Semantic Network Analysis in Social Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 72–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, D.O.; Funk, C.L. Self-Interest in Americans’ Political Opinions. Beyond Self-Interest; Mansbridge, J.J., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor Mayo, M. Activating self-interest: The role of party polarization in preferences for redistribution. Party Politics 2024, 30, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.W.; Barnett, G.A. ICA Fellows’ Networking Patterns in Terms of Collaboration, Citation, and Bibliographic Coupling and the Relevance of Co-Ethnicity. Scientometrics 2024, 129, 5433–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, D.M. Social identification effects in group polarization. J. Personal. Social. Psychol. 1986, 50, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.; Sood, G.; Lelkes, Y. Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 2012, 76, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.F.; Norris, P. Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash; HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP16-026; Harvard University, John F. Kennedy School of Government: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Colantone, I.; Ottaviano, G.I.P.; Stanig, P. The Backlash Against Globalization. In Handbook of International Economics; Gopinath, G., Helpman, E., Rogoff, K., Eds.; North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Dochow-Sondershaus, S.; Teney, C.; Borbáth, E. Cultural Backlash? Trends in Opinion Polarisation between High and Low-Educated Citizens since the 1980s: A Comparison of France, Italy, Hungary, Poland and Sweden. SocArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettarelli, L.; Van Haute, E. Regional inequalities as drivers of affective polarization. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2022, 9, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.D.; De Jonge, C.K.; Velasco-Guachalla, V.X. Deprivation in the midst of plenty: Citizen polarization and political protest. Br. J. Political Sci. 2021, 51, 1080–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Toorn, J.; Jost, J.T. Twenty years of system justification theory: Introduction to the special issue on “Ideology and system justification processes”. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2014, 17, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, D. Surveillance Technology and Surveillance Society. In Modernity and Technology; Misa, T.J., Brey, P., Feenberg, A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. Communication, power and counter-power in the network society. Int. J. Commun. 2007, 1, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.; Cox, D.R. An analysis of transformations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1964, 26, 211–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. Culture, Institutions and Social Equilibria: A Framework; No. w28832; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Hypothesis | Theoretical Framework(s) |

|---|---|

| H1 | Media Framing Theory; Discourse Theory |

| H2 | Cultural Globalization Theory; Optimal Information Theory (network density) |

| H3 | Affective Polarization; Optimal Information Theory (internal compression) |

| H4 | Relative Deprivation Theory; Resource Mobilization; OIT (signal generation) |

| H5 | Political Opportunity Structure; OIT (information control; regime response) |

| Variables | N | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLARIZATION (log hits) | 14 | 8.86 | 14.33 | 10.76 | 1.66 |

| DIGITAL_AUTH (log hits) | 14 | 10.22 | 17.09 | 13.11 | 2.83 |

| GOOGLE_PAGES (log, bil.) | 13 | −1.43 | 0.63 | −0.14 | 0.74 |

| PROTESTS (log hits) | 14 | 11.41 | 18.77 | 14.4 | 2.3 |

| DEGLOBAL_NYT (log count) | 14 | 2.4 | 6.95 | 4.5 | 1.37 |

| DEGLOBAL_FACEBK (log count) | 14 | 0.69 | 7.77 | 4.1 | 2.32 |

| DEGLOBAL_NEWS (log count) | 14 | 2.2 | 6.87 | 4.3 | 1.37 |

| DEGLOBAL_FACTOR (PCA score) | 14 | −0.59 | 2.84 | 0 | 1 |

| ENTROPY (bits) | 14 | 1.12 | 2.29 | 1.65 | 0.41 |

| PROTECTIONS (count) | 14 | 1609 | 25,066 | 12,794.21 | 7819.87 |

| Variables | Protect | Polar | DIGI_AUT | Protest | DEG_NYT | DEG_FB | DEG_NEWS | DEG_GOO | GEG_FAC | Pages | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROTECTIONS | -- | ||||||||||

| POLARIZATION | 0.946 ** | -- | |||||||||

| DIGITAL_AUTH | 0.930 ** | 0.848 ** | -- | ||||||||

| PROTESTS | 0.952 ** | 0.882 ** | 0.901 ** | -- | |||||||

| DEGLOBAL_NYT | 0.814 ** | 0.772 ** | 0.861 ** | 0.802 ** | -- | ||||||

| DEGLOBAL_FACEBOOK | 0.970 ** | 0.880 ** | 0.913 ** | 0.942 ** | 0.832 ** | -- | |||||

| DEGLOBAL_NEWS | 0.804 ** | 0.769 ** | 0.848 ** | 0.788 ** | 0.998 ** | 0.818 ** | -- | ||||

| DEGLOBAL_GOOGLE | 0.937 ** | 0.871 ** | 0.935 ** | 0.926 ** | 0.910 ** | 0.929 ** | 0.897 ** | -- | |||

| DEGLOBAL_FACTOR | 0.768 ** | 0.793 ** | 0.729 ** | 0.770 ** | 0.839 ** | 0.772 ** | 0.859 ** | 0.794 ** | -- | ||

| GOOGLE_PAGES | 0.908 ** | 0.763 ** | 0.833 ** | 0.896 ** | 0.623 * | 0.932 ** | 0.593 * | 0.850 ** | 0.581 * | -- | |

| ENTROPY | 0.916 ** | 0.834 ** | 0.893 ** | 0.832 ** | 0.809 ** | 0.861 ** | 0.803 ** | 0.896 ** | 0.704 ** | 0.778 ** | -- |

| Variables | Prot. | DEG_FAC | Polar | DIG_AUT | Protest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROTECTIONISM | -- | ||||

| DEGLOBALIZATION FACTOR | 0.730 ** | -- | |||

| POLARIZATION | 0.901 ** | 0.493 | -- | ||

| DIGITAL_AUTH | 0.689 ** | 0.61 * | 0.519 * | -- | |

| PROTESTS | 0.697 ** | 0.420 | 0.512 * | 0.579 * | -- |

| ENTROPY | 0.782 ** | 0.703 ** | 0.594 * | 0.669 ** | 0.467 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Danowski, J.A.; Park, H.-W. Deglobalization Trends and Communication Variables: A Multifaceted Analysis from 2009 to 2023. Information 2025, 16, 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050403

Danowski JA, Park H-W. Deglobalization Trends and Communication Variables: A Multifaceted Analysis from 2009 to 2023. Information. 2025; 16(5):403. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050403

Chicago/Turabian StyleDanowski, James A., and Han-Woo Park. 2025. "Deglobalization Trends and Communication Variables: A Multifaceted Analysis from 2009 to 2023" Information 16, no. 5: 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050403

APA StyleDanowski, J. A., & Park, H.-W. (2025). Deglobalization Trends and Communication Variables: A Multifaceted Analysis from 2009 to 2023. Information, 16(5), 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16050403