Abstract

Background: The persuasive systems design approach draws together theories around persuasive technology and their psychological foundations to form, alter and/or reinforce compliance, attitudes, and/or behaviors, which have been useful in building health and wellness apps. But with pandemics such as COVID and their ever-changing landscape, there is a need for such design processes to be even more time sensitive, while maintaining the inclusion of empirical evidence and rigorous testing that are the basis for the approach’s successful deployment and uptake. Objective: In response to this need, this study applied a recently developed rapid persuasive systems design (R-PSD) process to the development and testing of a COVID support app. The aim of this effort was to identify concrete steps for when and how to build new persuasion features on top of existing features in existing apps to support the changing landscape of target behaviors from COVID tracing and tracking, to long-term COVID support, information, and prevention. Methods: This study employed a two-fold approach to achieve this objective. First, a rapid persuasive systems design framework was implemented. A technology scan of current COVID apps was conducted to identify apps that had employed PSD principles, in the context of an ongoing analysis of behavioral challenges and needs that were surfacing in public health reports and other sources. Second, a test case of the R-PSD framework was implemented in the context of providing COVID support by building a COVID support app prototype. The COVID support prototype was then evaluated and tested to assess the effectiveness of the integrated approach. Results: The results of the study revealed the potential success that can be obtained from the application of the R-PSD framework to the development of rapid release apps. Importantly, this application provides the first concrete example of how the R-PSD framework can be operationalized to produce a functional, user-informed app under real-world time and resource constraints. Further, the persuasive design categories enabled the identification of essential persuasive features required for app development that are intended to facilitate, support, or precipitate behavior change. The small sample study facilitated the quick iteration of the app design to ensure time sensitivity and empirical evidence-based application improvements. The R-PSD approach can serve as a guided and practical design approach for future rapid release apps particularly in relation to the development of support apps for pandemics or other time-urgent community emergencies.

1. Introduction

With more than 1.4 million confirmed cases and 85,000 confirmed deaths globally in April 2020, the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a crisis worldwide [1]. To reduce the spread of COVID, the U.S. public health control team strategized that immediate infection mitigation was needed through the implementation of multiple public health initiatives, including social distancing, case testing, case isolation, travel restrictions and infection suppression [2]. But to implement the right strategies at the right time, it was important to determine the proportion of cases that should be isolated, and the proportion of their contacts that would need to be quarantined through contact tracing and tracking. Early studies on the estimated requirements for successful prevention of the spread of COVID found that digital contact tracing and tracking provided the best outcomes because a three-day delay in notification that was estimated to be required by manual contact tracing would not result in epidemic control [3]. In contrast, digital contact tracing and tracking using an immediate notification process would do better than manual methods [3], if used by a high proportion of the population [4]. Thus, epidemic control, through digital contact tracing and tracking that enabled rapid identification and immediate alerts for prompt isolation when exposed to diagnosed cases, emerged as an imminent need.

This led to a race to develop contact tracing and tracking apps. By 2023, numerous COVID contact tracing and tracking apps had been implemented both at government and private sector levels [5]. The functionality behind most of these COVID apps was simple. Users downloaded the app on their phone and provided details about their most recent COVID exposure or COVID test results. The apps then used Bluetooth technology (sometimes coupled with GPS data) to detect and identify the presence of other app users that might have been in close proximity for at least 15 min; and provided an advisory to the user regarding whether they were at risk of exposure. Some apps provided additional features to their users, like allowing them to enter and track their symptoms. Depending on the intent of the app, tracing apps informed users who had been in close proximity to an individual who tested COVID-positive; and tracking apps notified the user if it was safe to travel or if they needed to restrict their mobility. This simple approach was used to help keep the pandemic in check, because people could be infected and transmit the disease even before they showed symptoms. And timely notifications gave people a chance to self-isolate, reduce onward spread, get tested early, be informed of the current COVID variants, and thereby reduce the need for costly lockdowns [4].

But the explosion of quick-release COVID apps raised a number of known and unanticipated drawbacks. Early adopters of COVID apps reported having concerns about their privacy and the risk of continued government surveillance [6]. From a community perspective, concerns included requiring the right proportion of the population (at least 30–60%) to use contact tracing and tracking for successful containment [7]; user willingness to volunteer diagnosis information [8]; and barriers to reaching vulnerable, low-income, and minority populations due to racial inequalities [9]. In addition to these drawbacks, studies conducted to assess the acceptability and continued use of COVID apps reported that aside from downloading the apps mainly out of necessity (such as the need to report COVID test results before air travel through a travel-recommended reporting app); people have been unwilling to install such apps unless the app addressed three main factors: fears about surveillance, hacking, and anxiety around spread [8].

Additionally, as these issues were becoming apparent, there was another set of latent needs that were also emerging within the US population. These needs were twofold. The first of them was a high need for information about COVID and its effects. The need for COVID-related information had increased dramatically at this time because virtually every decision of daily life required consideration of exposure to COVID for each person or for their family members (even simple decisions required a consideration of exposure to COVID, such as where to shop for groceries, whether it was safe to go to the gym, whether one’s children would be safe from COVID if they were allowed to play at a neighbor’s home, etc.). Additionally, much of the time, there was no clear source of credible information from which answers about COVID could be obtained, and there was also no way to determine how credible COVID information was when it was available. This resulted in the second latent need that emerged at this time, namely, a high need to verify the credibility of COVID-related information that was available. Ultimately, the fear and anxiety that were already present (due to concerns about government surveillance, fears about securing and protecting personal information given to COVID apps from hacking, and fear of exposure to the virus itself) were being exacerbated by the fact that at this same time, there was an escalating need for information about COVID and its effects, and also, concurrently, an escalating rise in uncertainty about the credibility of COVID-related information that was provided and made available.

Even though the evolving landscape of COVID presented new needs and concerns, the majority of studies on COVID-related technology frameworks, applications, and design approaches primarily focused on issues related to privacy, information access, and preventing hacking. Few have focused on the specific design process needed to produce such rapid release technologies for meeting these needs [10], and how the design of such apps could continually address the evolving needs of users through design principles that would engender trust and bolster adoption and adherence [11]. While the lack of design principles guiding such rapid release technologies is likely due to inherent challenges in introducing technologies in complex emergencies such as a pandemic; design theory could be the differentiating factor that changes or enhances use, adherence to safety measures, and promotes overall trust in such apps.

General design processes and techniques such as participatory design, agile design methodology, minimal viable product design, lean UX methods, and design sprints have been used for the development of rapid release technologies. Among these design processes, the participatory design process is commonly implemented because it follows a user-centric approach for app development [12]. However, it can be time-intensive because of its emphasis on user-involvement, as well as stakeholder involvement [13]. Other design processes that blend agility and design thinking have shown that there is opportunity to generate and test new design ideas in five days, with trade-offs such as building on low-fidelity prototypes [14]. Additionally, there are many challenges inherent to complex emergencies themselves that preclude the use of time-intensive processes, or the time-intensive techniques within them. Designing within the context of emergencies requires speed, flexibility, user feedback, and rapid test-and-re-design cycles be prioritized so that the product can be quickly optimized [15]. Thus, a faster and more responsive design process is necessary for the successful development and deployment of rapid release technologies during emergency situations such as the COVID pandemic. This will likely remain true for future pandemics and community emergencies.

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated widespread behavioral changes, many of which were influenced by concerns surrounding digital interventions. People hesitated to adopt these technologies due to issues like trust, usability, and motivation, which created barriers to engagement [16,17]. Persuasive design techniques can help overcome these challenges by leveraging psychological principles—such as motivation [18], habit formation [19], and social influence [20]—to make digital interventions more intuitive, engaging, and trustworthy. Research has shown that interventions incorporating persuasive design elements can enhance user adoption and promote sustained behavioral change [21,22]. Persuasive design offers techniques that can facilitate these shifts in behavior by addressing the key barriers to adoption and engagement. For instance, public reluctance to download digital COVID-related applications could be mitigated by increasing willingness through strategic design interventions. Concerns about government surveillance and data privacy could be alleviated by enhancing transparency and communicating clear privacy safeguards. Similarly, fears of data breaches and hacking could be countered by reinforcing trust in the security measures embedded within these applications. Beyond security concerns, pandemic-related anxiety regarding virus transmission could be reduced by providing credible, easily understandable information alongside access to support services. Additionally, the heightened demand for reliable information—essential for daily decision-making, such as determining safe places to shop, assessing risks associated with social activities, or ensuring children’s safety—underscores the need for well-designed platforms that effectively deliver such insights. Addressing uncertainty about the credibility of COVID-19 information is equally critical, necessitating mechanisms that verify source reliability and nudge users toward credible, evidence-based resources. By integrating these elements, persuasive design can play a pivotal role in fostering user trust, engagement, and behavioral adaptation during public health crises.

An additional attribute of a persuasive system design (PSD) process that made it pivotal for this particular application is the fact that it is specifically intended for contexts in which behavior change is desirable or needed, particularly behavior change that can be facilitated by modern interactive information technologies [23]. In healthcare, several apps have implemented PSD techniques to drive behavior change and improve user engagement. For example, SmokeFree, a smoking cessation app, integrated real-time progress tracking, social support, and financial savings feedback to reinforce positive behavior, aligning with the self-determination theory [18]. Mental health applications like Woebot, an AI-powered chatbot, used social influence and tailored cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions to enhance user engagement and treatment adherence [24]. Omada Health, a digital diabetes prevention program, employed personalized coaching, habit formation strategies, and social accountability to drive long-term lifestyle changes, demonstrating the effectiveness of tailored, persuasive interventions [25]. These examples highlight how PSD principles, including social proof, reward systems, and tailored interventions, have been effectively integrated into digital health solutions to support sustained behavior change and improved health outcomes.

More recently, a study on mobile health interventions for Japanese office workers demonstrated that integrating PSD principles—such as self-monitoring, personalized feedback, and competition-based social support—led to a significant reduction in sedentary behavior, showcasing the effectiveness of dynamically synchronized PSD strategies with wearable technology [26] Another study on dynamic persuasive strategies in mHealth app development explored the impact of tailoring PSD techniques to users’ psychological traits, emphasizing that primary task support and dialogue support were the most effective for engagement, while system credibility and social support required careful implementation due to varying user perceptions. The study advocated for dynamically adaptive interventions that adjust persuasive strategies in real time based on user feedback [27]. These studies underscore the growing sophistication of PSD applications, moving from static interventions to highly personalized, real-time adaptive systems that enhance user engagement, trust, and long-term behavior change.

In a complex medical situation involving socio-technical systems like the COVID pandemic, the needs for behavior change were enormous, in addition to needs for communication, support, outreach, and public health instruction at a time when direct contact between individuals was heavily restricted. Many of the needs for behavior change have already been mentioned above, but a succinct summary of behavior change needs which arose from the pandemic are listed below (though only some of these behavioral changes were tackled in this initiative):

- -

- The need to invite and increase the behavior of downloading and using digital COVID apps within the community (something that was being avoided by many people at the very time when direct contact with other people was restricted).

- -

- The need to catalyze and increase users’ behaviors of sharing information with their COVID app, as well as sharing their questions with their app (based on increased confidence and comfort with the privacy of their data within the app, as well as the security of this information, and the safeguards protecting it, thus reducing/eliminating their fears of surveillance and hacking).

- -

- The need to nudge and increasingly precipitate users’ behaviors of using a digital app to look for and find solutions to their COVID-related needs.

- ○

- To increase their information-seeking behaviors within the app, increasing their search for appropriate, credible information about COVID-related topics (rather than relying on their own guesses, using hearsay, or using information from unverified sources).

- ○

- To increase their behavioral tendency to seek services and support for their COVID needs and those of their families.

- -

- The need to increase user’s behaviors of trying to verify the credibility/authenticity of information and services prior to accepting them and/or using them.

- -

- The need to increase the behaviors of using a digital app to connect with others.

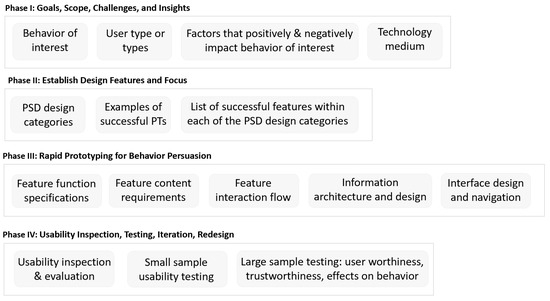

To address the challenge of producing a new app design rapidly, and a design that would lead to behavior change for its users, the research team applied a recently developed Rapid Persuasive System Design (R-PSD) approach (Figure 1) to the COVID-19 pandemic context by building a COVID support app as a test case. This test case was intended to evaluate the effectiveness and applicability of the R-PSD approach in producing a functional prototype app as an outcome. The COVID support app was designed using persuasive system design principles, but with modifications within the proposed R-PSD framework to facilitate rapid ideation, prototyping, and user feedback collection for subsequent improvements. The app prototype was tested using digital and virtual media to ensure timely development and deployment. This approach demonstrates how designers and practitioners can design, develop, and deploy rapid release technologies based on empirical evidence and testing practices. This method aims to ensure better uptake and adoption of technologies closer to the time they are needed.

Figure 1.

Rapid persuasive system design (R-PSD) framework.

2. Approach

The project team comprised Human Factors professionals and UX designers implemented the rapid persuasive system design (R-PSD) approach. The R-PSD approach was applied to the development of a smartphone app within the COVID pandemic context as a test case. The application of the R-PSD approach involved conducting a review and technology scan of successful PSD examples, rapid prototyping, and iterative user testing and redesign.

2.1. R-PSD Model

Several design methodologies exist for rapid technology deployment, each with its strengths and limitations. The Agile UX approach emphasizes iterative development and close user collaboration but often lacks structured guidance for integrating persuasive elements critical to behavior change [28]. Lean UX, on the other hand, prioritizes rapid experimentation and learning but may not provide sufficient mechanisms for systematically incorporating behavior change theories and persuasive design principles [29]. Traditional PSD offers a well-defined structure for developing persuasive interventions but is often too time-intensive for rapid deployment scenarios, as it relies on sequential implementation phases that may not be feasible during urgent public health crises [23].

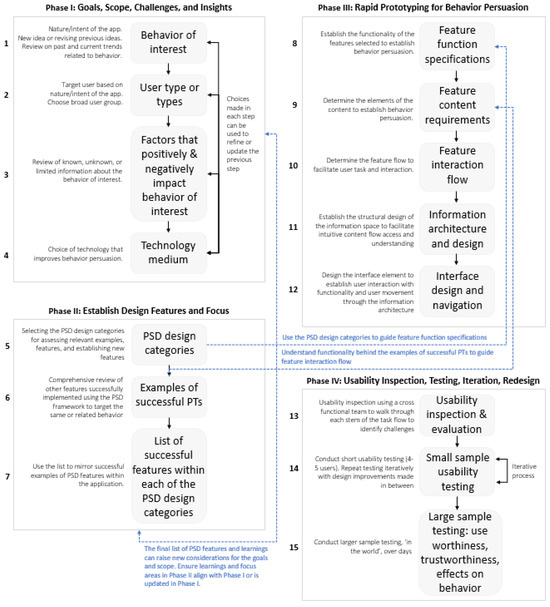

The R-PSD framework was developed to address these gaps by integrating the strengths of existing methodologies while ensuring speed, flexibility, and structured persuasive design integration. The R-PSD methodology is organized into four distinct phases, each addressing specific aspects of the design process. These are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Rapid persuasive system design (R-PSD) framework for iterative design and testing.

The initial phase focuses on defining broad behavior change goals. This involves conducting extensive literature reviews, technology scans, and needs assessments (e.g., including an analysis of the context within which the app will be used) to identify gaps in existing apps, their functions, and technology features. Leveraging Fogg’s PSD principles [21], this phase aims to identify and select behaviors that are important, specific, measurable, and achievable, refining broad goals into actionable objectives. This systematic approach is a new one, providing standardized procedures that have been missing in prior versions of PSD. This new approach offers techniques for evaluating persuasive technologies to ensure that selected behaviors are relevant and effectively addressed within the system’s design. Once key behaviors and persuasive requirements are mapped, the process moves to feature selection, ensuring that persuasive strategies align with user needs.

The second phase translates PSD principles into concrete software requirements, focusing on four key design categories: primary task support, dialogue support, system credibility support, and social support [23]. By creating a feature matrix, designers can map these categories into software features, identifying gaps and ensuring a comprehensive approach to feature selection. This matrix facilitates the comparison of different behavior change technologies, guiding necessary adjustments to align with the project’s goals and insights gathered in Phase I. This structured process helps integrate successful elements from existing technologies with new design ideas into a cohesive system. The outputs of this phase feed directly into prototyping, ensuring that the identified persuasive strategies are concretely implemented in the app’s early iterations.

In the third phase, the R-PSD framework introduces a structured approach to prototyping, adopting a bottom-up methodology. Various prototyping techniques are employed, including low-fidelity methods, high-fidelity digital prototypes, and live-data prototypes. This phase incorporates Garrett’s UX design framework [30], addressing strategy, scope, structure, skeleton, and surface. These steps ensure that functional specifications, content requirements, interaction design, information architecture, and interface design are meticulously addressed. Iterative testing and redesigning processes are integral to this phase, involving user testing to gather feedback and making improvements based on that feedback. Early user testing informs usability and behavior-change effectiveness, guiding the final refinement process.

The final phase involves iterative testing and redesigning, creating an initial version of the product and conducting user testing to gather feedback. This phase emphasizes the importance of a structured approach to user testing, systematically identifying and addressing usability issues. By establishing clear procedures for testing and iteration, this phase ensures that design improvements are methodically integrated, enhancing the overall effectiveness and usability of the final product. Within this final phase, as many as three or more methods may be used. First, usability inspection and evaluation methods may be applied, and then user-in-the-loop testing with small samples would be carried out as a part of ongoing iterative test and re-design. Then, subsequently, after the app prototype is fully functional, user-in-the-loop testing with larger samples would be conducted. This typically can be done in two ways, if time and resources allow. First, it can be done using the same methods used with small sample evaluations (but can utilize a wider and more diverse sample of users and can encompass usage over a longer time period (e.g., a month vs. a single study session). Second, it can also potentially include an additional large-scale “field operational test” in which a large sample of users would be given access in order to interact with the app in “real-life”, over an extended period of time, as part of their everyday activities. This would enable observation of their actual naturalistic patterns of use “in the wild”, using a specially-designed data acquisition “wrapper” around the app to record the features that are used, the sequences that are followed, the time that is spent per interaction, etc., and other types of data of this sort. (While a large-sample test of this sort was planned for this project, it was not possible to conduct due to resource constraints, and due to resolution of the pandemic which changed the conditions needed for the test. It, nonetheless, remains a key element of the R-PSD process). Most importantly, this kind of larger naturalistic usage study would be used to evaluate the extent to which the key behavioral changes that the app targeted were actually achieved by those who used the app, and would examine whether these behavioral changes are maintained over time. For example, in a large-scale EMA, measures would be obtained to evaluate whether the app succeeded in precipitating the following behavioral (and emotional) changes that it had targeted:

- (a)

- An increase in users’ level of knowledge about COVID (and their confidence in the information that they have), and a decrease in users’ feelings of uncertainty about the information needed/used for decisions affected by COVID.

- (b)

- An increase in the use of credible facts for decision-making, and a reduction in the use of guessing and hearsay as a basis for decision-making about everyday life decisions affected by COVID.

- (c)

- An increase in users’ feelings of comfort and confidence concerning COVID-related decisions and matters, and a reduction in users’ feelings of worry and fear.

- (d)

- An increase in users’ feelings of being connected and mobile, and a reduction in the feelings of being isolated, disconnected, and immobile or ’trapped’.

2.2. Literature Review for Extracting Successful PSD Feature Examples in COVID Apps

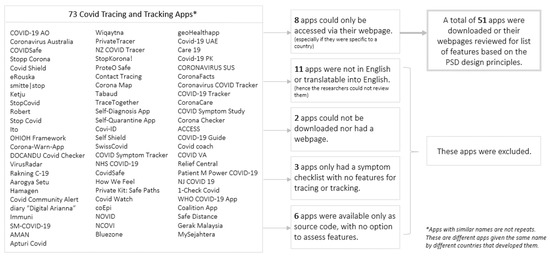

A systematic review was conducted to assess the PSD design principles implemented in current COVID apps. The review focused on apps that were specifically designed for providing support, tracking and/or tracing COVID, and were in-use or deployed as of 2020. A total of 73 COVID apps were considered. The list of apps was compiled together through Google searches using the key words “COVID apps”, “COVID applications”, “COVID support systems”, and “COVID-19 apps”; Wikipedia’s list of COVID apps [31], and from Android and Apple app stores. The goal was to collect a broad and representative sample of apps that were publicly available and widely adopted during the pandemic.

To improve the quality and accessibility of the review, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. Apps were excluded if they were not accessible in the U.S. due to geographic restrictions, could not be downloaded or installed, lacked English-language support, or required payment or subscription, as this would limit public accessibility during a time of widespread health crisis. After applying these criteria, a total of 51 apps remained and were reviewed. Each was either downloaded or, where applicable, accessed via a web-based platform to evaluate the extent to which its features reflected PSD principles. Selection was not based strictly on popularity or user adoption metrics, but rather on ensuring accessibility and diversity of function across global and national COVID-19 responses. The selection, inclusion and exclusion process of the 51 apps that were reviewed is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

List of the COVID apps that were reviewed and the inclusion and exclusion considerations.

2.3. App Prototyping

A live data app prototype was built using a web-based prototyping tool called Proto.io [32]. Proto.io was preferred because it provided the flexibility to build a live data prototype that included embedded external links and real-time data integration—features that required more setup and technical effort in other tools like Figma or Adobe XD. While other prototyping platforms were considered, they offered similar levels of design fidelity but lacked the seamless support for dynamic data feeds, which was a key requirement for this project. Live data prototypes are more complex than a high-fidelity prototype because data and embedding external links are included to create dynamic experiences that resemble the final product [33]. This approach allowed the designers and developers to collaboratively assess how the application responded to actual data and rapidly iterate on features based on that behavior. Such a prototyping approach allows designers and developers to jointly determine how the application works with actual data, and identify any issues or problems that may arise. Live data prototypes also allow for rapid iteration and testing of new features or changes to existing features.

In this prototype, live data were sourced directly from the COVID-19 Pandemic Global Chart [34], a reputable government-affiliated public data source. Proto.io facilitated the live data feedback from this data source by tapping directly into its API, enabling automatic updates and ensuring that the most recent and validated information was displayed in the prototype without requiring manual intervention. This helped simulate a realistic user experience during testing and eliminated the need for additional validation of the data during the prototyping phase.

2.4. Iterative User Testing

As part of the R-PSD process, an iterative small sample user test was conducted with four participants to enable rapid user testing and design iteration. Small sample studies recommend a sample of 4–7 participants for the testing and iteration of the design process [35]. Participation required access to a computer with a webcam and internet connection. Due to the pandemic and the inability to conduct in-person testing, the study was conducted remotely, and administered by a moderator from the research team.

This study was determined to be a product evaluation, and did not meet the criteria for being “research on human beings that would lead to generalizable principles of human behavior”. It, therefore, did not require review by an Institutional Review Board. Nonetheless, extra care was taken to ensure that study procedures conformed to all principles governing ethical treatment of humans participating in studies. More information is provided in the material at the end of the paper.

2.4.1. Participant Recruitment

For the small sample study, participants were recruited from each of the four ‘user types’ identified by the research team as having unique needs in addition to the needs of the more general public Table 1. Due to limited research at the time of this study on the types of users that have unique COVID-related needs, the research team identified the user types based on media reports and concluded that focusing on their specific needs could help ensure that the app would be beneficial to as many users as possible. Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The team was able to recruit individuals from all categories except User type 3 for the study.

Table 1.

Types of users found to have specific needs and requiring a more targeted approach.

2.4.2. Remote-Moderated Study Set Up and Testing Protocol

The small sample study was conducted remotely using the video conferencing software tool Zoom Version 6.4.6. Participants were notified of the study setup, time, and requirements in advance. The user testing format followed for each participant is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Remote-moderated usability testing setup (120 min).

At the start of each Zoom session, a moderator was present and enabled screen sharing between themself and the participant, such that both could communicate with each other. The moderator provided a welcome message and consent forms before administering pre-test questionnaires using Microsoft Forms. Participants were then given a 20 min session to familiarize them with the general operation of the app covering the high-level details regarding navigation through the app features, manipulation of specific features, and retrieving information from certain features. During user testing, participants were asked to conduct a set of ten information seeking tasks identified by the study team as the core features of the app, and those that users would typically do in real life if they were using the app. The order, scenario, and tasks are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Scenarios and tasks for rapid user testing.

Each task (in Table 3) was presented to the user within the context of a scenario that was predetermined by the research team. At the end of each task, users were asked to verbally confirm task completion by stating ‘done’, and asked to answer questions about their experience, attitudes, and feelings toward the app. The task order was the same across participants, and organized from simple to more complicated tasks. All the responses during user testing (recorded by the moderator), and pre- and post-test questionnaires (entered by the user) used online Microsoft Forms to store and save the data. Audio and video from each Zoom session were recorded and transcribed.

2.4.3. Pre-Test Questionnaires, Usability Evaluation Metrics, and Post-Test Questionnaires

Prior to conducting the usability testing, participants were administered four questionnaires. The Health Lifestyle and Personal Control Questionnaire (HLPCQ) was used to assess lifestyle habits of users, with a final open response question about noticeable lifestyle changes during COVID [36]. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) questionnaire was used to understand users’ perception of stress including current levels of experienced stress [37]. The Use and Opinion of Digital Health questionnaire is commonly used to assess effective design elements digital health interventions (e.g., choice of the most appropriate e-tool, topics of interest) for different users [38]. Lastly, the Technology Use questionnaire was used to survey general acceptability of COVID-related apps [39].

For obtaining user performance measures during the usability testing, commonly used quantitative and qualitative usability metrics recommended by the ISO standard on Software engineering — Product quality Part 4: Quality in use metrics interface evaluation standard [40] was used to evaluate the usability testing outcomes and guide the design iteration. After usability testing, users were asked to fill out four questionnaires. The User Interface Satisfaction was used to determine user satisfaction of the app [41]. The Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use [42], Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire (PSSUQ) [43], and mHealth App Usability Questionnaire (MAUQ) [44] were used to determine users’ perceived satisfaction, evaluation, and usability of the app, respectively.

The project team identified these sets of questionnaires based on past usability studies. These questionnaires were administered during the small sample study to assess potential areas of improvement, and provide the project team with a validated instrument for conducting comparative evaluations across iterations. Although all the questionnaire responses were collected, only those relevant for design iteration are reported in this paper to maintain scope. A summary of the pre-, during-, and post-test questionnaires and measures for the small sample user testing is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Pre-test questionnaires, usability evaluation metrics, and post-test questionnaires.

3. Results

A COVID support app prototype called SafeTEI was built using the proposed R-PSD approach. The time-sensitive nature of such an app was addressed using the R-PSD approach by enabling rapid movement from app ideation to prototyping and testing phases in a cost-effective manner within a five-month timeline by a five-person study team. Key learnings from implementing the R-PSD approach in building and testing a COVID-support app prototype are highlighted below.

3.1. R-PSD Phase I: Establishing the Behavior of Interest, User Types (Their Goals or Use Cases), and Technology Medium for SafeTEI

The main behavioral objective was to increase the access, learning, and reporting of COVID-related information by individuals both at a community and individual level. To achieve this objective, specific changes in behavior or state were identified, including the following:

- -

- Decreasing the behavioral tendency to make decisions based on guesses or hearsay, and increasing the reliance on credible facts;

- -

- Reducing users’ feelings of uncertainty about information needed for COVID-related decisions, and increasing their sense of being well-informed;

- -

- Decreasing feelings of worry and fear, and increasing feelings of comfort and confidence in making COVID-related decisions;

- -

- Reducing feelings of isolation and immobility and increasing users’ sense of connection and mobility.

After analyzing the shared needs and goals across the general population and user types with unique needs; the design team identified core needs that included information on COVID rates and policy changes, vaccination updates and variants, safe locations in their area, a platform for community members to connect and exchange information about COVID, and a place to store personal COVID-related information. These needs can be transformed into functions and features of the app in the subsequent stages of R-PSD. Each of the needs can also be broken down into specific tasks that a user would perform using the app, such as finding COVID-related travel restrictions for an upcoming trip, locating a nearby booster shot site, or finding an online chat forum for COVID discussion and sharing tips. The technology medium selected for SafeTEI was a smartphone.

3.2. R-PSD Phase II: Selecting the PSD Design Categories, and Persuasive Features from Successful Examples

To determine the appropriate features for the primary task, system credibility, social, and dialogue support, a systematic review was conducted to assess the PSD design principles implemented in current COVID apps. A comparison of the 51 COVID apps from different countries was conducted using the four PSD categories: primary task support, dialogue support, system credibility support, and social support (outlined in Table 5). The results of the comparison (Table 5) show that most of the apps had a suite of features that differed at many levels. While some had an extensive log-in process that required 3–5 min of user information and symptom entry; others were short (less than 1 min), and sometimes did not require any log in information. Among the 51 apps that were compared, only two COVID apps, Italy’s Digital Arianna and Coronavirus Australia, had incorporated most of the PSD design principles. Most of the apps focused heavily on system credibility support, especially those powered by Google’s Android and Apple’s iOS. However, the other PSD design categories were not incorporated to the same extent. The comparison revealed three key findings: Firstly, apps lacked sufficient dialog support; secondly, there was little to no social support; and finally, the apps were not designed to be supported across different platforms such as tracking wearables or smartwatches.

Table 5.

Comparison of features across COVID apps that are released and in use. Only 10 (out of 51) apps that were compared among are shown below. These 10 apps reflect those with the highest number of features across the PSD design categories.

The trends across the PSD design categories in COVID-19 apps revealed a consistent pattern: while system credibility support was prioritized—likely due to the need for users to trust official, often government-endorsed platforms—dialog and especially social support features were largely absent. This underrepresentation may stem from the urgency of early pandemic app development, where rapid deployment and information accuracy were prioritized over interactive or socially-driven engagement strategies. Furthermore, privacy concerns and the sensitive nature of health data likely limited the integration of social features such as peer comparison or user communities. Recognizing this gap, the research team examined leading mHealth and fitness apps, which commonly integrate dialog support (e.g., reminders, progress charts, activity recommendations) and some social support features (e.g., score comparison, social motivation). These insights were adapted to the SafeTEI context by integrating dialog support elements like progress visualization and timely prompts, while carefully tailoring social support features to align with the app’s public health goals such as promoting collective safety behaviors without compromising individual privacy.

The reviewed COVID apps in Table 5 provided valuable examples for implementing successful PSD design features within the primary task support and system credibility support categories for SafeTEI. But this was not the case for dialog support and social support features. The COVID apps lacked features that could facilitate social mobilization, mapping, communication, monitoring, and response. Since mHealth and fitness applications have been shown to have a number of successful examples of PSD design features for dialog support and social support interventions; a second assessment was conducted. This second assessment involved extracting features from the top 50 health and fitness apps (paid and free) rated by consumers and listed in the app stores (Table 6).

Table 6.

Feature comparison across mHealth and fitness apps to extract successful examples of social Support and dialog Support features implemented in the top 50 highest ranked mhealth and fitness apps.

Table 6 shows the results of the second assessment of health and fitness apps, which were categorized into three groups based on their focus: physical fitness (17 apps), health and wellness (23 apps), and both health and fitness (10 apps). The apps had between two and six design features, with dialog support being the most commonly observed feature, allowing users to track their health and fitness progress over time (indicated by the grey rows in Table 6). Such features have been found to contribute to behavior change by enhancing task efficacy and the formation of intentions [45,46], although these alone are insufficient for behavior change. Other features such as social support and motivation support, including celebrating successes, have been shown to help people implement their intentions [47,48].

Less frequent behavior change techniques among health and fitness apps, especially those focused on only one outcome (health or fitness) involved providing additional relevant information, prompts, and challenges related to the outcome. Additionally, scoring and performance measures were rare, as were most social support features. However, these apps were more likely to be available on multiple platforms. For apps focused on both health and fitness outcomes, dialog support features such as performance scoring were more commonly observed behavior change techniques. However, social support features and multi-platform capabilities were less common in these apps.

Reviewing these apps had several limitations. First, the categorization of app features based on PSD design principles does not necessarily imply that the behavior change technique was consistently implemented across all apps. Secondly, app features were categorized based on their online documentation instead of the downloaded versions, and the usability of the apps was not evaluated. Thirdly, while the apps were selected based on their high user ratings, no assessment was conducted to determine if positive ratings translate to effective health and fitness behavior change outcomes, which is beyond the scope of this study.

Additionally, it is important to consider that the context and patterns of user engagement differ significantly between health/fitness apps and COVID-19 support apps—and this impacts how transferable PSD features are between domains. Health and fitness apps typically involve long-term, self-motivated use with regular user interaction and feedback loops [49]. In contrast, COVID-19 apps often serve a more situational or utilitarian function—such as contact tracing, symptom tracking, or information dissemination—with episodic and often externally prompted use (e.g., during public health alerts or testing events). This difference in engagement frequency and depth means that while dialog and social support features from fitness apps can inform the design of SafeTEI, they may need to be adapted to fit the context of a health crisis, where trust, clarity, and immediacy are critical.

R-PSD steps in Phase II for the development of SafeTEI aimed to select the key persuasion techniques and features to be incorporated into the app. The main findings from reviewing successful PSD examples and their PSD design category was that in addition to providing primary task support and system credibility support, it was essential for the app to offer dialog support and social support features, especially during a health-related emergency such as the COVID pandemic. Previous mobile health and fitness apps have been lacking in these areas, which makes it all the more important for SafeTEI to incorporate them. As a result, the following feature categories were included in the SafeTEI app:

- -

- Primary task support: providing users forms of behavior reduction, tunnelling, tailoring, personalization, and self-monitoring of COVID-related needs;

- -

- Dialog support: providing users with reminders, suggestions, and a social role to provide and obtain COVID-related support;

- -

- System credibility: providing users with affordances that promote trust, expertise, and credibility from relevant COVID-related information and resources;

- -

- Social support: providing users with a way to assess their behavior and outcomes related to COVID through features enabling comparison, cooperation, and inclusiveness.

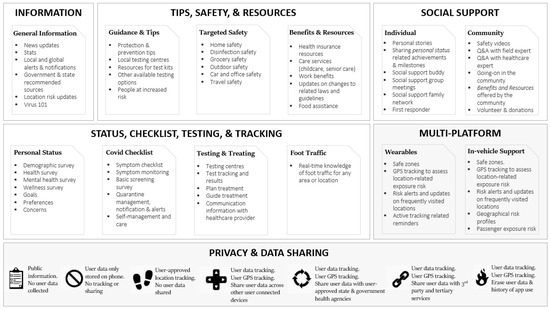

3.3. R-PSD Phase III: Building the App Prototype for Behavior Persuasion Using Successful Examples

Successful examples of PSD design features from the COVID support, mHealth, and fitness apps reviewed in R-PSD Phase II were categorized into four ‘levels’ by the research team: information; tips, safety, and resources; social support; and status, checklist, testing, and tracking (Figure 4). This classification of features into ‘levels’ served two purposes. First, to group features based on the type of information or support they provide or require from the user. Second, to structure the functional specifications, content requirements, interaction flow, information architecture, and interface design in a way that would allow users to access the app without signing in for accessing lower ‘levels’ such as information, and tips, safety, and resources. But requiring account creation to protect privacy for higher levels that contain features requiring user data entry.

Figure 4.

The research team used the concept of ‘levels’ to categorize successful examples of PSD for informational as well as data security purposes. Levels helped guide the development of the SafeTEI COVID support app. The shaded boxes ‘multi-platform’ and ‘privacy and data sharing’ represent additional ‘levels’ that were uncovered, intended for implementation in the next version of the app.

Drawing from successful examples in Phase III, the team uncovered new insights that led to the consideration of additional features, such as integrating the app with wearable devices to display certain valuable features and providing in-vehicle alerts for COVID safety (illustrated as ‘levels’ in Figure 4). Additionally, the team considered introducing more granular and flexible transparency options for users to choose their privacy and data sharing preferences. But implementing these feature levels was deemed beyond the scope of the current prototype due to limited project resources.

3.3.1. Prototyping SafeTEI

The SafeTEI app prototype was built using a web-based prototyping tool called Proto.io. Proto.io allowed for the research team to quickly build a functional and interactive prototype with live data. The prototyping process took approximately two months, and included incorporating features from external websites to reflect real-world interaction with the app. Figure 5 shows the landing page and menu screen for the SafeTEI app prototype. The four levels of features identified in Phase II of successful PSD examples were mapped into five menu items in SafeTEI:

Figure 5.

The landing page and menu items for the SafeTEI app prototype.

- -

- ‘COVID Rates and Policy Updates’, representing the information level with lowest data security and privacy concerns (Level 1);

- -

- ‘COVID, Vaccination Sites, and Info’, representing the tips, safety, and resources level with low data security and privacy concerns (Level 2);

- -

- ‘COVID Chat’, representing the social support level with medium to high data security and privacy concerns (Level 3);

- -

- ‘COVID SafeMap’ and ‘My COVID Chart’, representing the status, checklist, testing, and tracking level with highest data security and privacy concerns (Level 4).

Level 1: Prototyping the Information Layer

The ‘information’ level 1 of SafeTEI was designed to meet the users’ primary need for up-to-date COVID-related information. This was achieved by selecting credible information sites for users to explore and access on various pandemic topics, such as news or reports (identified by the CDC); updated rates of COVID cases, hospitalizations, deaths, etc. at both the global (international, by country) and local (by U.S. state, county, zip code) levels; government and regional alerts/notifications about COVID; local and global travel restrictions and requirements; and updated information on the epidemiology of COVID. Resources about COVID information were considered credible if they were recommended by the U.S. government, CDC, medical institutions such as John Hopkins, and the WHO.

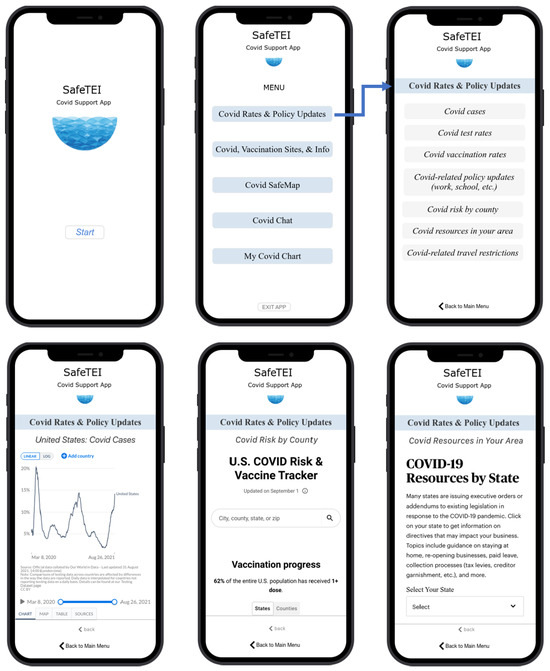

The ‘information’ level 1 of SafeTEI had a total of eight screens (Figure 6). Each screen had interactive elements such as buttons to navigate and interact with the features and functionalities; as well as input fields where users could search for local or regional level information. The goal of the ‘information’ level was to provide users with accurate, reliable, timely, and locally relevant information that could help them stay informed, and make informed decisions to protect themselves and others. Figure 5 shows the functionality, content, information design, and navigational elements within the ‘information’ level of the SafeTEI prototype.

Figure 6.

Some of the ‘information’ level features, content, navigation, and design.

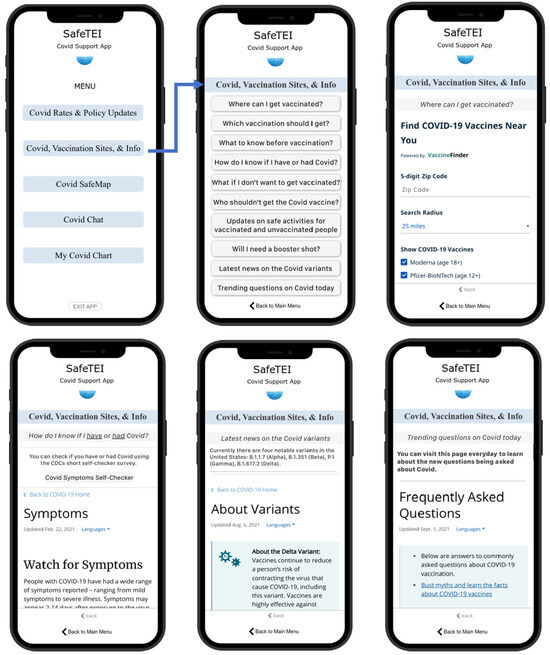

Level 2: Prototyping the Tips, Safety, and Resources Level for SafeTEI

The ‘tips, safety, and resources’ level 2 of SafeTEI was designed to provide users with COVID-related information about testing centers in their area, access to COVID testing kits, safety tips updates from the CDC and WHO, as well as staying informed of the changing benefits and resources being offered at the state and federal level. These features were considered level 2 because they required users to share certain information such as their zip code to access nearby COVID testing sites, and share their address to determine local resources related to COVID support. The ‘tips, safety, and resources’ level of SafeTEI had a total of ten interactive screens (Figure 7). Figure 7 shows the functionality, content, information design, and navigational elements within the ‘tips, safety, and resources’ level of the SafeTEI prototype.

Figure 7.

Some of the ‘tips, safety, and resources’ level features, content, navigation, and design.

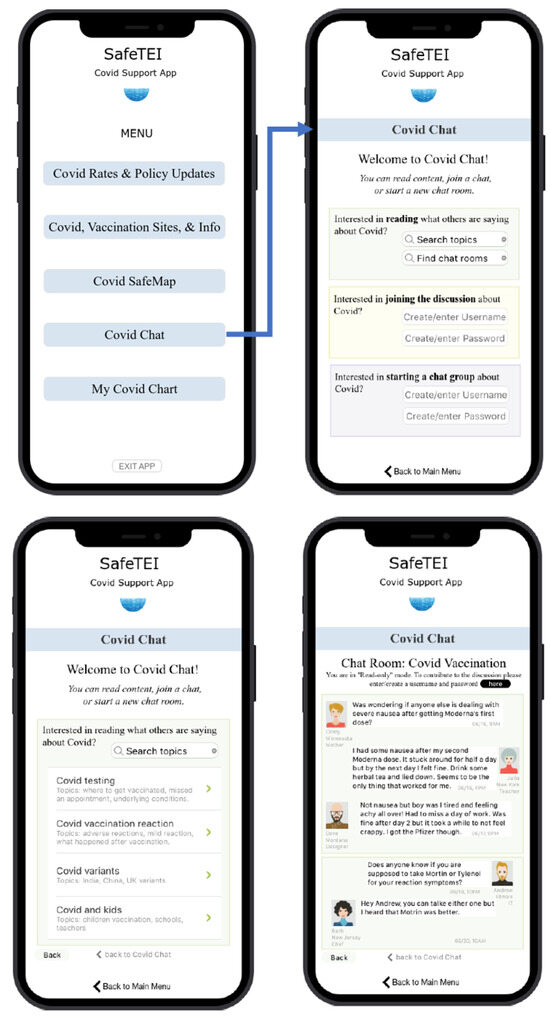

Level 3: Prototyping the Social Support Level for SafeTEI

The ‘social support’ level 3 of SafeTEI was designed to provide users with a platform to express their concerns, raise questions, and engage with the community. Users were given three options: read-only discussion posts, actively engaging in discussions in a chat group, and starting a chat or support group (Figure 8). These options were to ensure that future versions of the app could implement appropriate privacy and security checks for each option level. For example, read-only discussion posts could be made available to users without needing to create an account; whereas other social and chat options would require users to create an account to ensure accountability. The ‘social support’ level had a total of seven screens. Figure 8 shows the functionality, content, information design, and navigational elements within the ‘social support’ level of the SafeTEI prototype.

Figure 8.

Some of the ‘social support’ level features, content, navigation, and design.

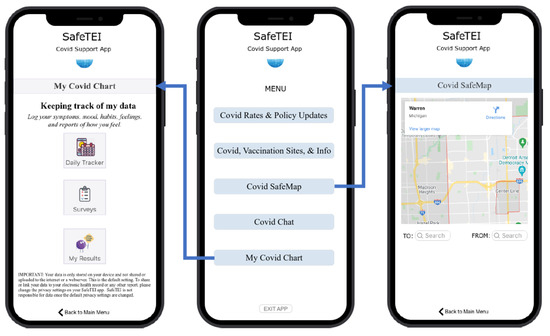

Level 4: Prototyping the Status, Checklist, Testing, and Tracking Level for SafeTEI

The ‘status, checklist, testing, and tracking’ level 4 of SafeTEI had a number of features that was categorized into two separate menu options: My COVID Chart and COVID SafeMap (Figure 9). My COVID Chart was designed to enable users to log symptoms related to COVID or post-vaccination symptoms; and chart their symptoms progress. The research team also identified a mobility gap, and built a ‘COVID SafeMap’ mapping feature to enable users to assess their chance of getting exposed to COVID when they left home.

Figure 9.

Some of the ‘status, checklist, testing, and tracking’ level features, content, navigation, and design.

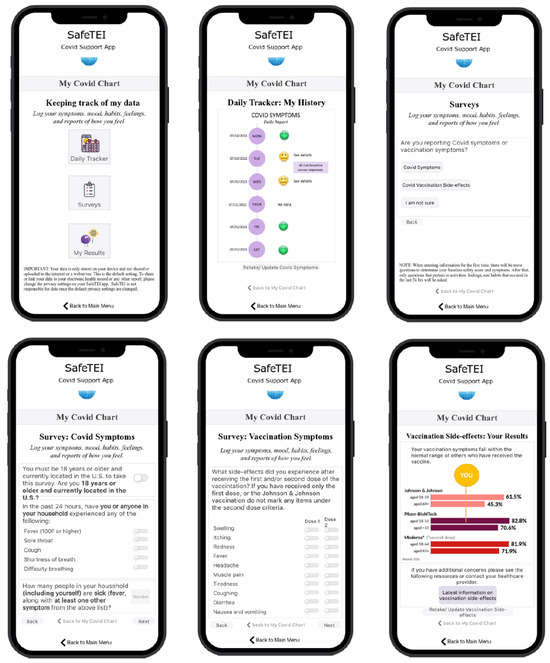

The ‘My COVID Chart’ had a total of 18 screens (Figure 10). The ‘My COVID Chart’ consisted of a ‘survey’ feature that users could use to enter a wide array of personal details regarding their mood, COVID symptoms, and vaccination symptoms. Due to the growing concerns around mental health during the height of the pandemic, the research team also included mental health and wellness surveys within this feature. Any information entered by the user could be visualized in the ‘Daily Tracker’ feature. Additionally, a ‘My Results’ feature was added to enable future versions of the app to sync with external health reporting symptoms, where users could store electronic records of their COVID test results and vaccination records.

Figure 10.

Some of the ‘My COVID Chart’ features, content, navigation, and design.

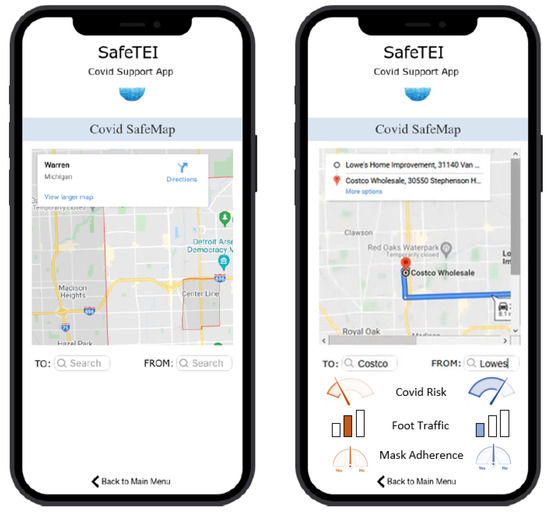

Due to the mobility restrictions during COVID, it was important to also provide users with a way to assess chance or risk of exposure to COVID when they left home. Thus, the research team built a ‘COVID SafeMap’ feature using Google Maps, where users would be presented with certain COVID-related metrics such as foot traffic (to determine how busy their destination might be), COVID risk meter (an estimate of COVID exposure likelihood at the location, i.e., a form of tracing), and Mask Adherence (an estimate of mask adherence among people at the location). Such a mobility feature did not exist in any known COVID-related applications. Figure 11 shows the interactive COVID SafeMap mapping feature. While the Foot Traffic data was publicly available data from Google that was incorporated into the prototype; the Mask Adherence and COVID Risk estimates were static features in the prototype, designed to represent the intended information for the COVID SafeMap to the user during testing.

Figure 11.

The ‘COVID SafeMap’ features, content, navigation, and design.

3.4. R-PSD Phase IV: Testing and Iterating the SafeTEI Prototype

The study team conducted the usability inspection and evaluation, and iterative small sample user testing. Findings from the testing and iteration process are reported below. Future work will involve conducting the large sample user testing.

3.4.1. Usability Inspection and Evaluation of SafeTEI

The usability inspection and evaluation R-PSD step consisted of two parts: a heuristic evaluation of the entire prototype, and a narrowly-focused cognitive walkthrough of specific task steps. Two evaluators from the research team that were not involved in the prototyping process conducted a heuristic evaluation of SafeTEI to identify and address problems or issues that may affect the usability of the interface. Heuristic evaluation identified a total of three major usability problems and 12 minor usability problems. Major usability problems included consistency within external links (broken links, links opening new windows), content prioritization (ordering of information within each page), and error handling (no options for error handling). Minor issues involved information spacing, navigation within certain features, and maintaining consistency moving from one screen to the other.

After addressing the minor and major usability issues, two separate evaluators conducted a rapid and narrowly-focused cognitive walkthrough of SafeTEI. The cognitive walkthrough consisted of a set of ten tasks identified by the research team as being representative of the day-to-day pandemic support users might access. These tasks also aligned with the app’s persuasive design objectives to increase access, learning, and reporting of COVID-related information by individuals both at a community and individual level. The evaluators rated all the tasks as successful. These tasks were then used in the small sample usability testing.

3.4.2. Small-Sample User Testing of SafeTEI

To prioritize user needs and determine which features to implement, the research team used a structured approach grounded in the R-PSD framework. Initial behavioral objectives were identified through user personas, stress and lifestyle assessments, and open-ended feedback collected during pre-testing. These objectives were then aligned with persuasive design principles across four categories: primary task support, dialog support, system credibility, and social support. Needs that directly mapped onto multiple PSD principles and were cited by more than one participant (e.g., information accessibility, visual clarity, and personalized safety tools) were prioritized for iteration. This mapping process ensured that design decisions were both user-informed and theoretically grounded, strengthening the link between behavior-change goals and persuasive feature integration.

The remote moderated small-sample usability testing was conducted on four participants representative of the user types identified in Table 1. The goal of the usability testing was to determine usability issues to inform the next set of design iterations for SafeTEI. Although a number of surveys were administered during the usability testing, only those results that reflected usability issues and redesign considerations are reported in Table 7.

Table 7.

Results of the small sample usability study to inform design iterations.

The results from the small-sample usability testing were used to conduct the next round of design iterations on the SafeTEI prototype. Some of the main feedback from users were related to the amount of information displayed within the app. While the breadth and depth of information was considered useful to have within a single app, users felt that this also made it challenging to navigate. This was reflected in the SUS results, where users rated the app’s perceived usefulness as generally high, but low screen satisfaction and usability (Table 7). To address this concern, the research team redesigned the menu bar and the ‘information’ and ‘tips, safety, and resources’ levels into tiles, and simplified the labels and content of sub-menu such as ‘Where can I get vaccinated?’ into ‘Vaccination Sites’. The interactive charts were intended to provide users a way to explore COVID rates at the country, state, county, and regional level. But such charts were found to be informationally dense. Hence the research team redesigned these features by replacing charts with single numbers. Lastly, users found the COVID SafeMap to be a helpful and novel mapping tool, but suggested that the icons used to depict ‘Foot Traffic’, ‘COVID Risk’, and ‘Mask Adherence’ be revised to be more intuitive and easier to read. The research team reviewed examples from different mapping tools to improve the design and display of the COVID SafeMap.

The issues were prioritized for iteration based on three factors: frequency of issue reported, impact on task completion or navigation, and alignment with key persuasive design goals. Issues that were high in all three areas such as confusing menu labels and difficult-to-read charts were addressed in the immediate design iteration. Others, such as chat group preferences (which received mixed feedback), were noted for future refinement, especially given their privacy and moderation requirements.

While the sample size was small, some variation in usability feedback across age groups was noted. For instance, the older adult user reported more difficulty navigating charts and understanding font size, while the younger healthcare provider participant expressed higher satisfaction with learnability and usefulness. These differences reinforced the need for design flexibility and accessibility across demographics and informed the decision to simplify the visual layout and data presentation for broader usability.

It is important to note that while such a small sample usability testing is widely used in UX research and early-stage design, the limited number of participants and potential lack of diversity may introduce biases or reduce the generalizability of findings. As such, findings from this phase were intended to inform iterative design improvements rather than to serve as definitive evaluations of usability across all user groups.

Following small-sample usability testing, R-PSD calls for large-sample testing. While this type of testing was planned for, it was not possible to conduct within the limited resources of the current project. Moreover, the most important type of large-scale testing to conduct for an app that is meant to achieve behavior change is that of a field operational test (wherein the app is accessible to users in their everyday lives for use in their natural environments, as they encounter issues and challenges within the pandemic). However, by the time the app reached this stage, the pandemic was itself resolving, and it was no longer possible to conduct a large-sample field test in any meaningful way, given that the conditions of need-for-the-app had changed. For that reason, there are no results to report for a large-sample test. Nonetheless, we wish to emphasize that executing a large-sample test is important, especially for an app that is intended to facilitate behavior change. It is within a large-sample field test that allows for ecologically natural use of the app that measures of whether the app is successful in enabling users to make the changes with which it is intended to assist them.

4. Discussion

The implementation of persuasive system design (PSD) principles for the development of products and services can vary based on various factors such as the size and complexity of the app, the available experience and skills of the team, and the project resources and timeline. Compared to traditional application development approaches, implementing PSD within technologies requires additional time and effort as it involves a more comprehensive understanding of the target behavior, user needs, and the persuasive techniques to promote the target behavior [23]. To address these challenges, the rapid persuasive system design (R-PSD) approach implemented Phase I and Phase II steps in parallel instead of sequentially to reduce time investment in the initial phases. For example, identifying broad target behaviors and conducting a review of current persuasive designs to address the behavior helped determine the breadth of the target behavior. Additionally, the R-PSD proposes spending less time to completely establish the initial behavior of interest, technology medium, and user types.

Studies and current industry implementation of app design do not report on the timelines for implementing such design methodologies and frameworks. From past experience, the study team found that the R-PSD framework produced an app just as fast (if not faster) than prior processes, and that future applications of the process would become faster with each subsequent application, due to the fact that gaps in the process were filled, that efficiencies were added to the process, and that the libraries of design concepts that were established would build up over time, becoming a fast-acting source of design ideas and a catalyst for future apps. Compared to other rapid development methodologies such as Agile UX and Lean UX, the R-PSD approach offers a unique advantage by integrating behavior-change theory (via the PSD framework) at the outset. While Agile and Lean UX focus on iterative development and user feedback, they do not inherently prioritize persuasive design strategies. R-PSD complements these approaches by combining rapid iteration with intentional selection of persuasive features, thus reducing the risk of developing functionally sound but behaviorally ineffective applications. That said, Agile and Lean methods may offer more flexibility in fast-paced commercial contexts, whereas R-PSD may be especially suited to health-oriented interventions where behavioral outcomes and credibility are critical. Additionally, the R-PSD process appears to be producing a prototype app that more fully meets the needs of its intended users than prior apps (for the intended need, which was provision of health-and-wellness support during a society-wide medical emergency). This conclusion is based on the first of two categories of empirical evidence that will ultimately assess this for the new app: the data gathered in the small-sample study. In line with existing research on PSD in digital health apps [49,50], features rooted in dialog support and primary task support appeared to resonate most with users. For instance, participants responded positively to infographics, reminders, and progress tracking tools elements known to enhance user engagement and self-efficacy. Conversely, features associated with social support such as chat groups were met with more skepticism, suggesting that these may require more contextual tailoring or privacy considerations. These findings align with the literature, indicating that while social features can foster motivation, they are highly sensitive to user context and trust in digital platforms [51]. Overall, the findings showed the following:

- (a)

- The new R-PSD produced a usable and useful app.

- -

- SafeTEI was rated “easy to use” (low in difficulty). Mean rated usefulness was 5.9—above the midpoint of the scale, and mean rated learnability was 8.1 (out of 9).

- -

- SafeTEI was rated high for its information’s “usefulness”. (+Two ratings mapped to this, and the means were 6 and 8 (out of 9).

- -

- SafeTEI was rated high for providing the functions and information needed to be supportive for its purpose. This was evaluated with an open-ended question, and no additional functions, features, or types of information were identified by participants as “not provided”.

While the user testing followed standard usability protocols and incorporated validated instruments, the limited sample size and potential lack of demographic diversity may constrain the generalizability of the results. These early stage findings are intended to guide iterative design refinements rather than to draw broad conclusions about user behavior.

While the usability evaluation focused on short-term perceptions of usefulness, learnability, and satisfaction, this study did not assess long-term user engagement or the app’s actual impact on behavior change. These are important aspects for evaluating the effectiveness of persuasive system design, especially in health-related contexts. Future research should incorporate longitudinal methods, such as multi-week user trials or in-the-wild deployment studies, to examine how sustained interaction with the app influences behavior over time. In the future, we expect to obtain evidence pertaining to the second category of evidence needed to determine whether the new app more fully meets the needs of its intended users than prior apps developed during the pandemic. The data for this category will come from the large-sample study that has not yet been conducted. However, the evidence that we will be focused on obtaining will be as follows:

- (b)

- The R-PSD produced an app that precipitated changes in behavior that were established as goals in its usage context (Section 5.1):

- -

- SafeTEI decreased the behavioral tendency of users to make COVID decisions based on guesses or hearsay, and increased their reliance on credible facts;

- -

- SafeTEI decreased feelings of worry and fear, and increased their feelings of comfort and confidence in making COVID-related decisions;

- -

- Reduced customer fears of use (and increased users’ willingness-to-use a digital health app during a society-wide medical crisis);

- -

- SafeTEI improved user’s beliefs in—and ratings of—the credibility of the information made accessible by the app;

- -

- SafeTEI reduced users’ feelings of uncertainty about information needed for COVID-related decisions, and increased their sense of being well-informed;

- -

- SafeTEI reduced feelings of isolation and immobility and increased users’ sense of connection and mobility.

For researchers and practitioners interested in adopting the R-PSD framework, we recommend several key steps: (1) begin by identifying broad user needs and behavioral objectives early in the process using quick-turnaround tools such as personas and survey-based insights; (2) conduct a focused review of persuasive features in existing apps across domains; (3) map selected features to the four PSD categories while considering privacy and implementation feasibility; and (4) incorporate rapid, small-scale usability testing to inform iterative refinements; (5) follow-up with large-sample field testing to determine if app-users successfully achieve the targeted behavioral change goals Based on experience in this study, potential refinements to the R-PSD process could include more structured guidance on selecting PSD strategies for different user types and use cases, as well as integrating automated tools for feature tracking across iterations. Future adaptations might also benefit from embedding user feedback loops more explicitly into each phase to better support personalization and adaptability under time constraints.

A major challenge for rapid release technologies is typically the lack of thorough testing and evaluations, which could result in usability and functionality issues. The prioritization of speed for rapid release often limits the opportunity to take into account the needs and perspectives of end users. The R-PSD approach addresses this concern by including user testing at both a small and larger scale during the testing and iteration phase. Another challenge is balancing rapid development with the need to establish data security, privacy protection, and other security risks. In this regard, the R-PSD approach introduces the concept of combining features into ‘levels’, which assigns different levels of privacy and data security settings based on the sensitivity of user information associated with each feature level. Lastly, most rapid release technologies are not always designed to accommodate or adapt to the changing needs of the user or emerging problems. The R-PSD approach proposes building technologies with six feature categories (general information, resources, user status, support opportunities, multi-platform capabilities, and multiple privacy settings) that would allow opportunities in practice to accommodate updates or changes over the long-term. The successful prototyping and testing of SafeTEI as a test case for the R-PSD approach represents a step forward; an advance that may be particularly useful to developers of future apps who must design a digital app under very tight time constraints in an environment where user needs are paramount.

5. Conclusions

As COVID variants continue to spread, mobile technologies are serving as a useful platform for the delivery of information and interventions. But these platforms need to keep up with the changing needs of the community in response to the evolving landscape of viruses such as COVID. This requires design and development approaches to be conducted under tighter time constraints and limited resources. The rapid persuasive system design process provides an opportunity to create comprehensive and effective applications quickly that take into account important factors such as knowledge discovery, usability testing, and team resources. As these design processes continue to evolve, they can be further optimized to better support the needs of individuals during society-wide pandemics or other society-wide health emergencies.

5.1. Implications and Applications

The pandemic has highlighted the need for effective communication, timely information dissemination, and behavior change interventions that need to evolve with the changing information landscape. In this regard, the rapid persuasive system design (R-PSD) process proposed in this study emphasizes time sensitivity, as well as a parallel development and design approach to ensure applications can be developed quickly and efficiently. This is carried out to allow for more effective and timely responses to changing circumstances. This has significant implications for the development of time-sensitive technologies and services. The modularity of the R-PSD approach, introducing the concept of ‘levels’ to further categorize features for organizational or structural purposes allows design modularity that can ensure that such applications can evolve continuously, building on past features as building blocks to meet the changing needs of the user.

5.2. Impact Statement

- -

- The R-PSD can support development of future apps (and products) that are needed under time-pressure for community-level public health emergencies, including future pandemics;

- -

- The application of a process like this can help build a library of useful persuasive design principles and features, which could greatly facilitate more timely design and development in the future;

- -

- The ability to integrate more frequent remote usability testing leads to improved iterative testing speeds and efficiencies, and promises faster development processes in the future;

- -

- Including final phase large-sample testing (especially using field testing techniques) to formally evaluate the extent to which an app helps its users achieve targeted behavior change goals will begin to offer more definitive feedback on how behavior change can be facilitated and accomplished.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.P., A.Z. and L.S.A.; methodology, R.P.P., A.Z. and L.S.A.; software, R.P.P.; formal analysis, R.P.P.; investigation, R.P.P. and A.Z.; data curation, R.P.P. and A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P.P.; writing—review and editing, R.P.P., A.Z. and L.S.A.; visualization, R.P.P.; project administration, L.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In the work reported here, two human-in-the-loop product evaluation studies were planned, and one of these has been carried out and is reported here. It was a small-sample evaluation of product usability and usefulness described later (in which 4 individuals interacted with a prototype smartphone app). When reviewed, these studies were determined to be marketing studies on a specific product (i.e., a digital health app for a smartphone)—rather than constituting systematic research on human beings, per se—that would lead to generalizable conclusions about human behavior (as defined under the “Common Rule” used in the United States by Institutional Review Boards that oversee the rights of humans in research). As a result of this classification (which was based on formal documentation, and which produced a decision-outcome that was documented; a ‘Determination Decision’), the two evaluations of the app were determined not to require Institutional Review Board review in the United States. Nonetheless, as an extra measure of care, the project team prepared the protocols for both evaluations so that they adhered fully to all Principles of Ethical Research. This meant that the protocols included the administration of Informed Consent to each participant prior to the evaluations, and also included private and personalized data-collection sessions, use of online tools for remote data collection sessions to protect the health of participants and study moderators, the confidential treatment of data using codes for data-labelling rather than personally identifying information, and secure storage of all data. Furthermore, all study personnel on the project team had fully up-to-date training in the ethical treatment of human study participants and were certified by an institution that had been accredited for their curriculum on ethical treatment of humans in research (CITI). Thus, the steps taken by the project team also meant that the work reported here was prepared and carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (according to The Declaration of Helsinki).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their fellow Touchstone colleagues who made significant contributions to the project. Alicia Fitzpatrick conducted the virtual study sessions as the online interviewer. John Fitzpatrick programmed all the scripts in PsychStudio and Microsoft Forms. Sean Seaman provided helpful feedback for reviewing the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/index.html (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Ferguson, N.M.; Laydon, D.; Nedjati-Gilani, G.; Imai, N.; Ainslie, K.; Baguelin, M.; Bhatia, S.; Boonyasiri, A.; Cucunubá, Z.; Cuomo-Dannenburg, G.; et al. Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) to Reduce COVID19 Mortality and Healthcare Demand; Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]