An Industrial Framework for Cold-Start Recommendation in Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Scenarios

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a model-agnostic industrial framework (MAIF) that establishes a global semantic mapping from attribute features to the cold-start feature field. It can be applied to various online embedding-based models without altering the existing organization of training samples, significantly improving prediction accuracy and calibration performance in cold-start scenarios.

- We design a non-invasive optimization strategy based on parameter reuse and gradient isolation. This approach enables MAIF to be “hot-plugged” into continuous training pipelines without retraining from scratch, effectively resolving the challenge of massive historical data accumulation while maximizing resource efficiency.

- We validate the effectiveness of MAIF through extensive offline experiments on real-world datasets and rigorous online A/B testing in a large-scale industrial system. The results demonstrate that our framework achieves comprehensive coverage for both zero-shot and few-shot scenarios. Furthermore, it focuses on the seesaw phenomenon, ensuring that the adaptation to cold-start entities does not compromise the performance of warm-up entities, effectively reducing the negative impact on business indicators during deployment.

2. Related Work

3. Model-Agnostic Industrial Framework

3.1. Embedding Layer

3.2. Feature Classification

- Missing Feature (): A subset representing the target fields (e.g., UserID or ItemID) characterized by high sparsity, where the latent information is frequently inaccessible due to containing many unseen features.

- Transfer Feature (): A subset designated to approximate the semantics of the missing features. These fields serve as the information source for reconstruction.

- Common Feature (): The set of remaining feature fields, defined as the .

3.3. Preliminaries

3.4. Loss Function

3.5. Network Structure

3.6. Auto-Selection

| Algorithm 1 Offline Training for Base and Cold-Start Tasks |

| Require: |

| , , : learning rates for gradient updates; |

| , : parameters of base task and Trans Block in cold-start task; |

| : embedding table; |

| : dataset sorted by timestamp; |

| : the gradient-based optimization function; |

|

| Algorithm 2 Online Serving with Auto-Selection |

| Require: |

| : online request with metadata and attributes; |

|

4. Experiments and Discussion

4.1. Offline Experiment

4.1.1. Datasets

- User cold-start scenario (upper right): existing items recommended to new users.

- Item cold-start scenario (lower left): new items recommended to existing users.

- User–Item cold-start scenario (upper left): new items recommended to new users.

4.1.2. Baseline Models

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.1.4. Offline Experimental Settings

4.1.5. Experiment Results

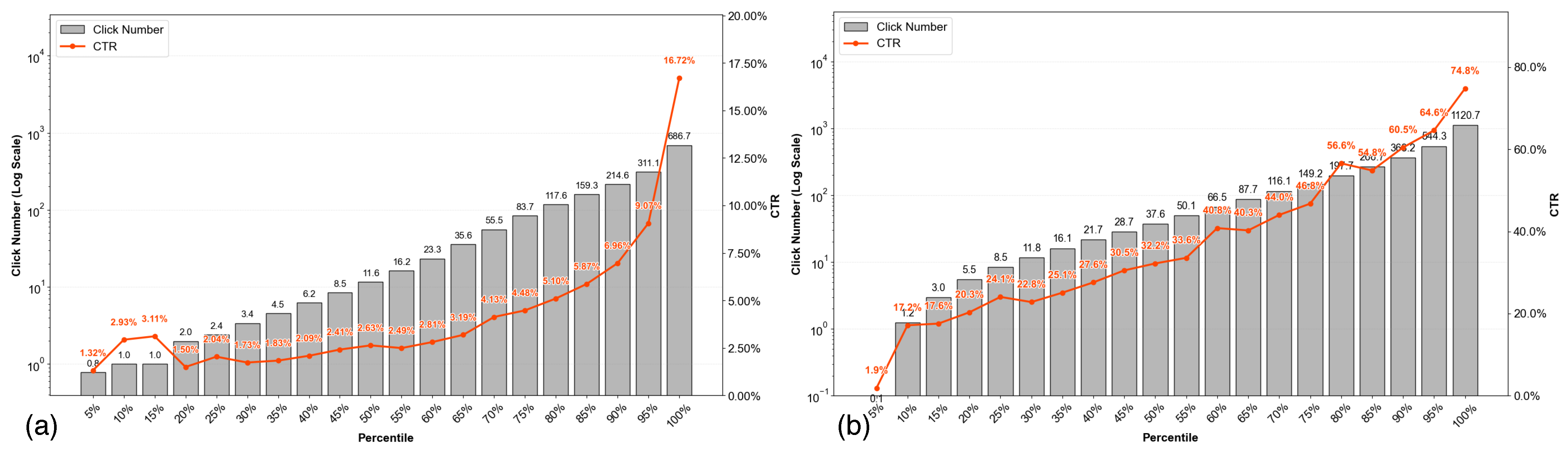

4.2. Online A/B Test

4.2.1. Online Experimental Settings

4.2.2. A/B Test Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, C.; Li, S.; Lei, W.; Chen, J.; Li, B.; Jiang, P.; He, X.; Mao, J.; Chua, T.S. KuaiRec: A Fully-observed Dataset and Insights for Evaluating Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–21 October 2022; pp. 540–550. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Im, J.; Jang, S.; Cho, H.; Chung, S. Melu: Meta-learned user preference estimator for cold-start recommendation. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 1073–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, R.; Pang, H.; Giunchiglia, F.; Liang, Y.; Feng, X. Cross-Domain Meta-Learner for Cold-Start Recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 35, 7829–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moreno, D.; López Batista, V.F.; Muñoz Vicente, M.D.; Sánchez Lázaro, Á.L.; Moreno-García, M.N. Social network community detection to deal with gray-sheep and cold-start problems in music recommender systems. Information 2024, 15, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Huang, F.; Huang, X.; Xu, Y.; Lin, Y.; He, P.; Li, Z. Generative adversarial framework for cold-start item recommendation. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 2565–2571. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, C.; Wu, F.; Tang, S.; Hua, L.; Jia, R.; Lv, C.; Wu, Z.; Chen, G. Billion-scale federated learning on mobile clients: A submodel design with tunable privacy. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, London, UK, 21–25 September 2020; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Volkovs, M.; Yu, G.; Poutanen, T. Dropoutnet: Addressing cold start in recommender systems. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4964–4973. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Ma, Q.; Gu, H.; Zheng, Z. Multi-view denoising graph auto-encoders on heterogeneous information networks for cold-start recommendation. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Singapore, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 2338–2348. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniak, M.; Mimno, D. Evaluating the stability of embedding-based word similarities. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2018, 6, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briand, L.; Salha-Galvan, G.; Bendada, W.; Morlon, M.; Tran, V.A. A semi-personalized system for user cold start recommendation on music streaming apps. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Singapore, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 2601–2609. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.X.; Li, S.; He, Y.; Chang, E.Y.; Wen, J.R.; Li, X. Connecting social media to e-commerce: Cold-start product recommendation using microblogging information. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2015, 28, 1147–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herce-Zelaya, J.; Porcel, C.; Tejeda-Lorente, Á.; Bernabé-Moreno, J.; Herrera-Viedma, E. Introducing CSP dataset: A dataset optimized for the study of the cold start problem in recommender systems. Information 2022, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Liu, W.; Chen, C.; Su, J.; Liao, X.; Hu, M.; Tan, Y. Mining User Consistent and Robust Preference for Unified Cross Domain Recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 8758–8772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xie, R.; Zhuang, F.; Ge, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lin, L.; Cao, J. Learning to warm up cold item embeddings for cold-start recommendation with meta scaling and shifting networks. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Montréal, QC, USA, 11–15 July 2021; pp. 1167–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Haldar, M.; Ramanathan, P.; Sax, T.; Abdool, M.; Zhang, L.; Mansawala, A.; Yang, S.; Turnbull, B.; Liao, J. Improving deep learning for airbnb search. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 2822–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Chio, E.K.I.; Cheng, H.T.; Du, Y.; Rendle, S.; Kuzmin, D.; Agarwal, R.; Zhang, L.; Anderson, J.; Singh, S.; et al. Zero-shot heterogeneous transfer learning from recommender systems to cold-start search retrieval. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtual, 19–23 October 2020; pp. 2821–2828. [Google Scholar]

- Huan, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Wu, Q.; Gu, L.; Gu, J.; He, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Mo, L. An Industrial Framework for Cold-Start Recommendation in Zero-Shot Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 3403–3407. [Google Scholar]

- Le, N.L.; Abel, M.H.; Gouspillou, P. Combining Embedding-Based and Semantic-Based Models for Post-Hoc Explanations in Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 1–4 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 4619–4624. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.T.; Sharma, A.; Sun, S.; Xia, L.; Zhang, D.; Pronin, P.; Padmanabhan, J.; Ottaviano, G.; Yang, L. Embedding-based retrieval in facebook search. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 2553–2561. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Huzhang, G.; Zeng, A.; Yu, Q.; Sun, H.; Li, H.Y.; Li, J.; Ni, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhou, Z. Clustered Embedding Learning for Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023; pp. 1074–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, K.; Liu, B.; Xiao, L.; Li, Y.; Jiang, J. Image feature learning for cold start problem in display advertising. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 25–31 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Zhu, X.; Chen, L.; Fang, Z.; Gao, Y. Metakg: Meta-learning on knowledge graph for cold-start recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 35, 9850–9863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, S.; Kordík, P. Overcoming the cold-start problem in recommendation systems with ontologies and knowledge graphs. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Advances in Databases and Information Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 4–7 September 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 591–603. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chiu, B.; Feng, S.; Wang, H. Few-shot named entity recognition via meta-learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2020, 34, 4245–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Giunchiglia, F.; Li, X.; Guan, R.; Feng, X. PNMTA: A pretrained network modulation and task adaptation approach for user cold-start recommendation. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022, Barcelona, Spain, 26–29 June 2022; pp. 348–359. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, F.; Li, S.; Ao, X.; Tang, P.; He, Q. Warm up cold-start advertisements: Improving ctr predictions via learning to learn id embeddings. In Proceedings of the 42nd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Paris, France, 21–25 July 2019; pp. 695–704. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Shi, C. Meta-learning on heterogeneous information networks for cold-start recommendation. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data mMining, Virtual, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 1563–1573. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, M.; Yuan, F.; Yao, L.; Xu, X.; Zhu, L. Mamo: Memory-augmented meta-optimization for cold-start recommendation. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 688–697. [Google Scholar]

- Felício, C.Z.; Paixão, K.V.; Barcelos, C.A.; Preux, P. A multi-armed bandit model selection for cold-start user recommendation. In Proceedings of the 25th Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, Bratislava, Slovakia, 9–12 July 2017; pp. 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, W.; Li, T.; Iyengar, S.S.; Shwartz, L.; Grabarnik, G.Y. Online interactive collaborative filtering using multi-armed bandit with dependent arms. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2018, 31, 1569–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Huang, L.; Rao, A.; Irissappane, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Qu, H. A deep reinforcement learning recommender system with multiple policies for recommendations. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 19, 2049–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buuren, S.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.J.; Pan, P.; Zhou, T.; Chen, H.; Luo, C. Zero shot on the cold-start problem: Model-agnostic interest learning for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtual, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 474–483. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, H.; Meng, X.; Tang, J.; Qiao, J. Dynamic System Modeling Using a Multisource Transfer Learning-Based Modular Neural Network for Industrial Application. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 7173–7182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wu, L.; Hong, R.; Wang, M. Making Non-overlapping Matters: An Unsupervised Alignment enhanced Cross-Domain Cold-Start Recommendation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 37, 2001–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, F.M.; Konstan, J.A. The movielens datasets: History and context. Acm Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst. 2015, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, F. The perceptron: A probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain. Psychol. Rev. 1958, 65, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Tang, R.; Ye, Y.; Li, Z.; He, X. DeepFM: A Factorization-Machine based Neural Network for CTR Prediction. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI, Melbourne, Australia, 19–25 August 2017; pp. 1725–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.T.; Koc, L.; Harmsen, J.; Shaked, T.; Chandra, T.; Aradhye, H.; Anderson, G.; Corrado, G.; Chai, W.; Ispir, M.; et al. Wide & deep learning for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Deep Learning for Recommender Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 15 September 2016; pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Li, W.J.; Xue, G.R.; Han, D. Coupled group lasso for web-scale ctr prediction in display advertising. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Beijing, China, 22–24 June 2014; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 802–810. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yang, X. Optimized cost per mille in feeds advertising. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and MultiAgent Systems, Auckland, New Zealand, 9–13 May 2020; pp. 1359–1367. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, X.R.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, G.; Ding, X.; Dai, B.; Luo, Q.; Yang, S.; Lv, J.; Zhang, C.; Deng, H.; et al. One model to serve all: Star topology adaptive recommender for multi-domain ctr prediction. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtual, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 4104–4113. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z.; Zhang, D.J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Chen, X.; Xu, Z. Cold start to improve market thickness on online advertising platforms: Data-driven algorithms and field experiments. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 3838–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Cold-Start Topic | Missing Feature | Transfer Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| KuaiRec | user topic | user_id | user_active_degree, is_live_streamer, is_video_author, register_days, onehot_feat0-17 |

| item topic | video_id | video_type, date, upload_type, video_width, video_height, video_tag_id, video_tag_name, show_cnt, play_cnt, valid_play_cnt, like_cnt, comment_cnt, follow_cnt, share_cnt, collect_cnt | |

| MovieLens-1M | user topic | userid | gender, age, occupation, zip-code |

| item topic | movieid | title, year of release, genres |

| Scenario | Model | AUC | RelaImp | PCOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warm-Up fully observed | MLP | 0.9334 ± 0.0017 | 0.0% | 1.0312 ± 0.010 |

| DeepFM | 0.9436 ± 0.0016 | 2.35% | 1.0539 ± 0.015 | |

| Wide & Deep | 0.9478 ± 0.0013 | 3.32% | 1.0220 ± 0.018 | |

| Dropout-Net | 0.9134 ± 0.0019 | −4.61% | 1.0456 ± 0.016 | |

| MICE (MLP) | 0.9333 ± 0.0017 | −0.023% | 1.0333 ± 0.011 | |

| MeLU (MLP) | 0.9303 ± 0.0016 | −0.72% | 1.0512 ± 0.016 | |

| MEG (MLP) | 0.9310 ± 0.0016 | −0.55% | 1.0669 ± 0.014 | |

| MAIF (MLP) | 0.9331 ± 0.0017 | −0.07% | 1.0307 ± 0.012 | |

| MAIF (DeepFM) | 0.9436 ± 0.0016 | 2.35% | 1.0824 ± 0.019 | |

| MAIF (Wide & Deep) | 0.9477 ± 0.0015 | 3.30% | 1.0422 ± 0.013 | |

| User Cold-Start few-shot | MLP | 0.8615 ± 0.0030 | 0.0% | 1.2104 ± 0.054 |

| DeepFM | 0.8767 ± 0.0029 | 4.20% | 1.2380 ± 0.059 | |

| Wide&Deep | 0.8988 ± 0.0031 | 10.32% | 1.2616 ± 0.056 | |

| Dropout-Net | 0.8702 ± 0.0033 | 2.41% | 1.1113 ± 0.020 | |

| MICE (MLP) | 0.8723 ± 0.0035 | 2.98% | 1.1321 ± 0.021 | |

| MeLU (MLP) | 0.8815 ± 0.0029 | 5.53% | 1.0913 ± 0.024 | |

| MEG (MLP) | 0.8988 ± 0.0026 | 10.32% | 1.0867 ± 0.021 | |

| MAIF (MLP) | 0.9002 ± 0.0028 | 10.71% | * 1.0689 ± 0.014 | |

| MAIF (DeepFM) | * 0.9015 ± 0.0029 | 11.07% | * 1.0754 ± 0.017 | |

| MAIF (Wide & Deep) | * 0.9106 ± 0.0028 | 13.58% | * 1.0898 ± 0.018 | |

| MAIF (Wide & Deep) w/o reused | * 0.8447 ± 0.0025 | −4.65% | * 1.0873 ± 0.017 | |

| MAIF (Wide & Deep) w/o | * 0.8965 ± 0.0026 | 9.68% | * 1.1004 ± 0.019 | |

| Item Cold-Start few-shot | MLP | 0.7040 ± 0.0030 | 0.0% | 1.7020 ± 0.18 |

| DeepFM | 0.7195 ± 0.0031 | 7.6% | 1.8175 ± 0.20 | |

| Wide & Deep | 0.7265 ± 0.0028 | 11.03% | 1.6987 ± 0.15 | |

| Dropout-Net | 0.7123 ± 0.0032 | 4.07% | 1.2031 ± 0.020 | |

| MICE (MLP) | 0.7198 ± 0.0035 | 7.74% | 1.3321 ± 0.051 | |

| MeLU (MLP) | 0.7388 ± 0.0031 | 17.06% | 1.2003 ± 0.018 | |

| MEG (MLP) | 0.7425 ± 0.0030 | 18.87% | 1.1775 ± 0.022 | |

| MAIF (MLP) | * 0.7490 ± 0.0029 | 22.06% | * 1.1249 ± 0.015 | |

| MAIF (DeepFM) | * 0.7528 ± 0.0025 | 23.92% | * 1.1182 ± 0.016 | |

| MAIF (Wide & Deep) | * 0.7592 ± 0.0027 | 27.06% | * 1.1307 ± 0.015 | |

| MAIF (Wide & Deep) w/o reused | * 0.6783 ± 0.0024 | −12.59% | * 1.1024 ± 0.014 | |

| MAIF (Wide & Deep) w/o | * 0.7394 ± 0.0025 | 17.35% | * 1.1507 ± 0.017 | |

| User–Item Cold-Start zero-shot | MLP | 0.8244 ± 0.0027 | 0.0% | 1.2800 ± 0.064 |

| DeepFM | 0.8204 ± 0.0022 | −1.23% | 1.2473 ± 0.058 | |

| Wide&Deep | 0.8268 ± 0.0032 | 0.74% | 1.2437 ± 0.060 | |

| Dropout-Net | 0.8275 ± 0.0033 | 0.96% | 1.1556 ± 0.023 | |

| MICE (MLP) | 0.8366 ± 0.0035 | 3.76% | 1.1844 ± 0.031 | |

| MeLU (MLP) | 0.8444 ± 0.0037 | 6.17% | 1.1881 ± 0.025 | |

| MEG (MLP) | 0.8504 ± 0.0039 | 8.01% | 1.1773 ± 0.026 | |

| MAIF (MLP) | * 0.8655 ± 0.0037 | 12.67% | * 1.0812 ± 0.023 | |

| MAIF (DeepFM) | * 0.8681 ± 0.0037 | 13.47% | * 1.0992 ± 0.021 | |

| MAIF (Wide & Deep) | * 0.8683 ± 0.0032 | 13.53% | * 1.0923 ± 0.020 | |

| MAIF (Wide & Deep) w/o reused | * 0.8064 ± 0.0025 | −5.55% | * 1.0996 ± 0.018 | |

| MAIF (Wide & Deep) w/o | * 0.8534 ± 0.0033 | 8.94% | * 1.1047 ± 0.023 |

| Scenario | Model | AUC | RelaImp | PCOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warm-Up fully observed | MLP | 0.7216 ± 0.0012 | 0.0% | 1.0340 ± 0.007 |

| DeepFM | 0.7268 ± 0.0013 | 2.34% | 1.0371 ± 0.009 | |

| Wide&Deep | 0.7279 ± 0.0015 | 2.84% | 1.0386 ± 0.009 | |

| Dropout-Net | 0.7151 ± 0.0017 | −2.93% | 1.0301 ± 0.007 | |

| MICE (MLP) | 0.7215 ± 0.0018 | −0.04% | 1.0548 ± 0.011 | |

| MeLU (MLP) | 0.7151 ±0.0012 | 2.93% | 1.0695 ± 0.007 | |

| MEG (MLP) | 0.7166 ± 0.0013 | 2.25% | 1.0719 ± 0.008 | |

| MAIF (MLP) | 0.7215 ±0.0015 | −0.04% | 1.0320 ± 0.008 | |

| MAIF (DeepFM) | 0.7269 ± 0.0015 | 2.39% | 1.0384 ± 0.007 | |

| MAIF (Wide&Deep) | 0.7279 ± 0.0013 | 2.84% | 1.0382 ± 0.009 | |

| User Cold-Start few-shot | MLP | 0.6602 ± 0.0022 | 0.0% | 1.2348 ± 0.060 |

| DeepFM | 0.6629 ± 0.0021 | 1.68% | 1.2595 ± 0.055 | |

| Wide&Deep | 0.6681 ± 0.0021 | 4.93% | 1.2712 ± 0.065 | |

| Dropout-Net | 0.6544 ± 0.0023 | −3.62% | 1.1522 ± 0.032 | |

| MICE (MLP) | 0.6741 ± 0.0025 | 8.67% | 1.1773 ± 0.036 | |

| MeLU (MLP) | 0.6710 ± 0.0020 | 6.74% | 1.0765 ± 0.013 | |

| MEG (MLP) | 0.6747 ± 0.0020 | 9.05% | 1.0868 ±0.015 | |

| MAIF (MLP) | * 0.6956 ± 0.0019 | 22.09% | * 1.0524 ±0.010 | |

| MAIF (DeepFM) | * 0.6994 ± 0.0018 | 24.46% | * 1.0673 ± 0.013 | |

| MAIF (Wide&Deep) | * 0.7013 ± 0.0019 | 25.65% | * 1.0529 ± 0.011 | |

| MAIF (Wide&Deep) w/o reused | * 0.6412 ± 0.0018 | −11.86% | * 1.0531 ± 0.011 | |

| MAIF (Wide&Deep) w/o | * 0.6887 ± 0.0019 | 17.79% | * 1.0732 ± 0.013 | |

| Item Cold-Start few-shot | MLP | 0.6337 ± 0.0024 | 0.0% | 1.3974 ± 0.092 |

| DeepFM | 0.6470 ± 0.0024 | 9.94% | 1.3647 ± 0.085 | |

| Wide&Deep | 0.6482 ± 0.0022 | 10.84% | 1.4017 ± 0.081 | |

| Dropout-Net | 0.6198 ± 0.0023 | -10.39% | 1.2019 ± 0.031 | |

| MICE (MLP) | 0.6540 ± 0.0022 | 15.18% | 1.2863 ± 0.037 | |

| MeLU (MLP) | 0.6627 ± 0.0020 | 21.69% | 1.1872 ± 0.028 | |

| MEG (MLP) | 0.6672 ± 0.0020 | 25.05% | 1.1510 ± 0.025 | |

| MAIF (MLP) | * 0.6774 ± 0.0021 | 32.65% | * 1.0770 ± 0.018 | |

| MAIF (DeepFM) | * 0.6856 ± 0.0020 | 38.81% | * 1.0695 ± 0.015 | |

| MAIF (Wide&Deep) | * 0.6885 ± 0.0021 | 40.98% | * 1.0691 ± 0.015 | |

| MAIF (Wide&Deep) w/o reused | * 0.6178 ± 0.0019 | −11.89% | * 1.0744 ± 0.014 | |

| MAIF (Wide&Deep) w/o | * 0.6782 ± 0.0022 | 33.28% | * 1.0952 ± 0.018 | |

| User–Item Cold-Start zero-shot | MLP | 0.6444 ± 0.0019 | 0.0% | 1.317 ± 0.072 |

| DeepFM | 0.6481 ± 0.0020 | 2.56% | 1.3228 ± 0.078 | |

| Wide&Deep | 0.6515 ± 0.0020 | 4.91% | 1.3614 ± 0.069 | |

| Dropout-Net | 0.6313 ± 0.0022 | −9.07% | 1.1407 ± 0.025 | |

| MICE (MLP) | 0.6616 ± 0.0021 | 11.91% | 1.2106 ± 0.035 | |

| MeLU (MLP) | 0.6583 ±0.0022 | 9.62% | 1.1196 ± 0.015 | |

| MEG (MLP) | 0.6682 ± 0.0021 | 16.48% | 1.0964 ± 0.012 | |

| MAIF (MLP) | * 0.6749 ± 0.0020 | 21.12% | * 1.0624 ± 0.016 | |

| MAIF (DeepFM) | * 0.6773 ± 0.0019 | 22.78% | * 1.0632 ± 0.015 | |

| MAIF (Wide&Deep) | * 0.6802 ± 0.0021 | 24.79% | * 1.0585 ± 0.017 | |

| MAIF (Wide&Deep) w/o reused | * 0.6272 ± 0.0018 | −11.91% | * 1.0663 ± 0.012 | |

| MAIF (Wide&Deep) w/o | * 0.6661 ± 0.0021 | 15.03% | * 1.0789 ± 0.019 |

| Model | AUC | RelaImp | PCOC | Impression | Click | CTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.7928 | 0.0% | 0.9229 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.01739 |

| Experimental | * 0.8157 | * 7.8% | * 1.0415 | * 1.203 | * 1.2205 | * 0.01763 |

| Model | TP50 (ms) | TP99 (ms) | TP999 (ms) | Failure (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 17.0 | 23.3 | 38.5 | 0.121 |

| Experimental | 19.2 | 24.3 | 38.5 | 0.134 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, X.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, X. An Industrial Framework for Cold-Start Recommendation in Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Scenarios. Information 2025, 16, 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121105

Cao X, Zhang W, Jiang F, Zhang X. An Industrial Framework for Cold-Start Recommendation in Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Scenarios. Information. 2025; 16(12):1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121105

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Xulei, Wenyu Zhang, Feiyang Jiang, and Xinming Zhang. 2025. "An Industrial Framework for Cold-Start Recommendation in Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Scenarios" Information 16, no. 12: 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121105

APA StyleCao, X., Zhang, W., Jiang, F., & Zhang, X. (2025). An Industrial Framework for Cold-Start Recommendation in Few-Shot and Zero-Shot Scenarios. Information, 16(12), 1105. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121105