The Relationship Between Information Technology Dimensions and Competitiveness Dimensions of SMEs Mediated by the Role of Innovative Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Principles, Literature Review, and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Competitiveness (CP)

2.1.1. Supply Chain (SCH)

2.1.2. Operation and Strategic Management of a Company (OSMC)

2.1.3. Product Competition (PC)

2.1.4. Critical Assessment of the Literature

2.2. Information Technology (IT)

2.2.1. Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

2.2.2. Human Resource Management (HRM)

2.2.3. IT as an External Enabler Within Institutional Contexts

2.3. Innovative Performance (IP)

Contradictions and Gaps in Innovation Performance Research

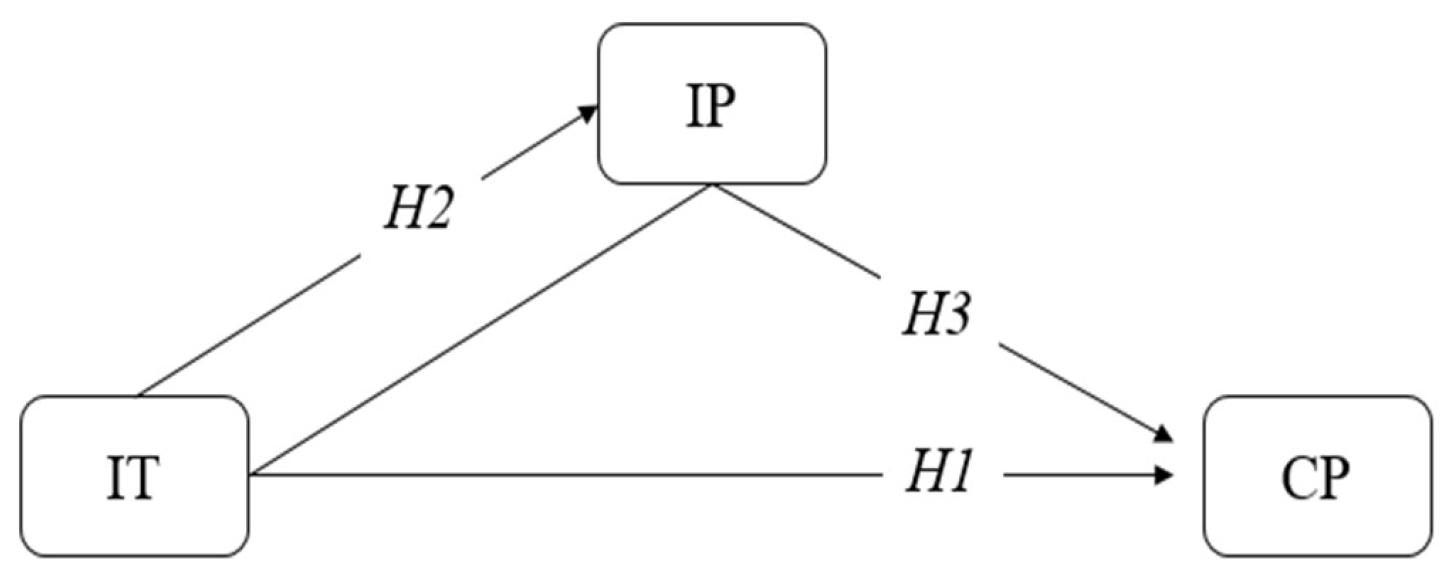

2.4. Hypothesis Development

2.4.1. Explaining the Relationship Between Information IT and CP

2.4.2. The Relationship Between IT and IP

2.4.3. The Role of IP in the Relationship Between IT and CP

2.5. Research Conceptual Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Implementation Method

3.1.1. Statistical Test for Sample Size Adequacy

3.1.2. Economic Context and Data Validity Considerations

3.2. Measurement of Variables

3.3. Justification for Using PLS-SEM

3.4. Reliability and Validity of the Measurement Model

3.4.1. Reliability

3.4.2. Convergent Validity

3.4.3. Construct Structure

3.5. Control Variables

4. The Findings

4.1. Summary of Demographic Findings

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n = 172) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 127 | 73.8 |

| Female | 45 | 26.2 | |

| Age | 20–25 years | 43 | 25 |

| 26–30 years | 54 | 31.4 | |

| 31–35 years | 36 | 20.9 | |

| Education Level | Above 35 years | 39 | 22.7 |

| Diploma or below | 4 | 2.3 | |

| Associate degree | 14 | 8.1 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 62 | 36 | |

| Master’s degree | 76 | 44.2 | |

| PhD | 16 | 9.3 | |

| Work Experience | ≤5 years | 60 | 34.9 |

| 6–10 years | 51 | 29.7 | |

| 11–15 years | 31 | 18 | |

| >15 years | 30 | 17.4 | |

| Position in Company | Senior Accountant | 29 | 16.9 |

| CEO | 24 | 14 | |

| Technology Manager | 18 | 10.5 | |

| Financial Manager | 24 | 14 | |

| Other | 77 | 44.6 | |

| Firm Size | Small (1–50 employees) | 94 | 54.7 |

| Medium (51–250 employees) | 78 | 45.3 |

4.2. Inferencing Data

| CP Model | IP Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | p-Value | Conf. Interval | Coefficient | p-Value | Conf. Interval | ||

| IT | 0.268 | 0 | 0.15 | 0.385 | 0.238 | 0 | 0.115 | 0.361 |

| Gender | −0.032 | 0.697 | −0.194 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.247 | −0.069 | 0.269 |

| Experience | −0.013 | 0.809 | −0.119 | 0.093 | −0.005 | 0.933 | −0.115 | 0.106 |

| Company Type | 0.037 | 0.648 | −0.121 | 0.195 | −0.029 | 0.729 | −0.195 | 0.136 |

| Age | 0.017 | 0.749 | −0.086 | 0.119 | −0.063 | 0.247 | −0.171 | 0.044 |

| Education | 0.012 | 0.793 | −0.075 | 0.099 | 0.023 | 0.623 | −0.068 | 0.114 |

| Constant | 1.445 | 0 | 0.822 | 2.067 | 0.912 | 0.006 | 0.262 | 1.563 |

| Model 1 | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | p-Value | Conf. Interval | |

| IT | 0.222 | 0 | 0.102 | 0.343 |

| IP | 0.199 | 0.02 | 0.031 | 0.366 |

| IT*IP | 0.068 | 0.004 | ||

| Gender | −0.052 | 0.524 | −0.211 | 0.107 |

| Experience | −0.012 | 0.827 | −0.116 | 0.092 |

| Company Type | 0.042 | 0.599 | −0.114 | 0.197 |

| Age | 0.029 | 0.58 | −0.073 | 0.13 |

| Education | 0.008 | 0.861 | −0.078 | 0.093 |

| Constant | 1.267 | 0 | 0.645 | 1.89 |

| Variables | CRM Model | HRM Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p-Value | Coefficient | p-Value | |

| Crm | 0.233 | 0.000 | ||

| Hrm | 0.246 | 0.000 | ||

| Gender | −0.031 | 0.739 | −0.042 | 0.643 |

| Experience | −0.044 | 0.451 | −0.039 | 0.506 |

| Companytype | 0.018 | 0.837 | 0.060 | 0.500 |

| Age | 0.042 | 0.452 | 0.040 | 0.479 |

| Position | −0.020 | 0.466 | −0.017 | 0.523 |

| Education | 0.018 | 0.718 | 0.010 | 0.845 |

| Constant | 2.646 | 0.000 | 2.575 | 0.000 |

| R2 | 7.72 | 9.41 | ||

| Obs | 172 | 172 | ||

| F Test | 3.04 | 0.005 | 3.54 | 0.001 |

| Variables | CRM Model | HRM Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | p-Value | Coefficient | p-Value | |

| Crm | 0.242 | 0.000 | ||

| Hrm | 0.231 | 0.000 | ||

| Gender | 0.104 | 0.299 | 0.090 | 0.367 |

| Experience | −0.045 | 0.487 | −0.041 | 0.521 |

| Companytype | −0.057 | 0.561 | −0.014 | 0.884 |

| Age | −0.030 | 0.628 | −0.033 | 0.599 |

| Position | −0.041 | 0.168 | −0.040 | 0.178 |

| Education | 0.022 | 0.684 | 0.015 | 0.781 |

| Constant | 2.662 | 0.000 | 2.682 | 0.000 |

| R2 | 8.50 | 8.20 | ||

| Obs | 172 | 172 | ||

| F Test | 3.27 | 0.003 | 3.18 | 0.004 |

4.3. Additional Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Benchmarking with Comparable Emerging Economies

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations of the Research

- Classification of SMEs.

- 2.

- Lack of ownership structure data.

- 3.

- Lack of industry-level data.

- 4.

- Context specificity and limited generalizability.

- 5.

- Potential self-report bias under economic instability.

5.4. Further to the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SMEs | Small And Medium-Sized Enterprises |

| IT | Information Technology |

| CP | Competitiveness |

| IP | Innovative Performance |

| CRM | Customer Relationship Management |

| HRM | Human Resource Management |

| SCH | Supply Chain |

| PC | Product Competition |

| OSMC | Operation And Strategic Management Of The Company |

| CIP | Employee Training |

| WIP | Financial Rewards And Incentives |

| NIP | Non-Financial Rewards |

| TIP | Technical Innovation |

| CMV | Common Method Variance |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

References

- Garg, C.P.; Kashav, V. Modeling the supply chain finance (SCF) barriers of Indian SMEs using BWM framework. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayoun, S.; Salehi, M.; ArminKia, A.; Novakovic, V. The mediating effect of innovative performance on the relationship between the use of information technology and organizational agility in SMEs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of Iran. Central Bank of Iran—Official Website. Available online: https://www.cbi.ir (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Statistical Center of Iran. Statistical Center of Iran—Official Website. Available online: https://www.amar.org.ir/english (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Gherghina, Ș.C.; Botezatu, M.A.; Hosszu, A.; Simionescu, L.N. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): The engine of economic growth through investments and innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.K.; Yadav, C.S.; Vishnoi, S.; Rastogi, R. Smart agriculture–Urgent need of the day in developing countries. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2021, 30, 100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwarteng, P.; Appiah, K.O.; Addai, B. Influence of board mechanisms on sustainability performance for listed firms in Sub-Saharan Africa. Future Bus. J. 2023, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gómez, P.; Arbelo-Pérez, M.; Arbelo, A. Profit efficiency and its determinants in small and medium-sized enterprises in Spain. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2018, 21, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanah, A.U.; Shino, Y.; Kosasih, S. The role of information technology in improving the competitiveness of small and sme enterprises. IAIC Trans. Sustain. Digit. Innov. (ITSDI) 2022, 3, 168–174. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.Q.; Yang, C.-H. Information technology and innovation outcomes: Is knowledge recombination the missing link? Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Behl, R. Strategic alignment of information technology in public and private organizations in India: A comparative study. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2023, 24, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trantopoulos, K.; von Krogh, G.; Wallin, M.W.; Woerter, M. External knowledge and information technology. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanbakht, M.; Ahmadi, F. Empirical assessment of external enablers on new venture creation: The effect of technologies and non-technological change in Iran digital entrepreneurship. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2025, 17, 819–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A. Information and communication technology adoption and its influencing factors: A study of indian SMEs. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2019, 7, 1238–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydiner, A.S.; Tatoglu, E.; Bayraktar, E.; Zaim, S. Information system capabilities and firm performance: Opening the black box through decision-making performance and business-process performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, L.; Wang, W. The impact of supply chain digitization and logistics efficiency on the competitiveness of industrial enterprises. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 97, 103759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A. Impact of technology adoption on the performance of small and medium enterprises in India. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahveci, E. Digital transformation in SMEs: Enablers, interconnections, and a framework for sustainable competitive advantage. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, A.A.; Bhattacharjee, A. Competitiveness improvement in public sector organizations: What they need? J. Public Aff. 2020, 20, e2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajitabh, A.; Momaya, K. Competitiveness of firms: Review of theory, frameworks and models. Singap. Manag. Rev. 2004, 26, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan, V.R.; Tan, K.C. Just in time, total quality management, and supply chain management: Understanding their linkages and impact on business performance. Omega 2005, 33, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadegan, A.; Syed, T.A.; Blome, C.; Tajeddini, K. Supply chain involvement in business continuity management: Effects on reputational and operational damage containment from supply chain disruptions. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2020, 25, 747–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagorio, A.; Zenezini, G.; Mangano, G.; Pinto, R. A systematic literature review of innovative technologies adopted in logistics management. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2022, 25, 1043–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Santo, B.; Waterman, R.; Chukhno, A.; Shnypko, O. Improving the competitiveness of balneological, spa and wellness centres by implementing innovative strategies (on the example of Varna municipality). In Proceedings of the Competitive Model of Innovative Development of Ukraine’s Economy, Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine, 7–8 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, A.L.; Roessner, J.D.; Jin, X.Y.; Newman, N.C. Changes in national technological competitiveness: 1990, 1993, 1996 and 1999. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2001, 13, 477–496. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, B.D. Henderson on Corporate Strategy; Abt Books: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick, D.C. High profit strategies in mature capital goods industries: A contingency approach. Acad. Manag. J. 1983, 26, 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skare, M.; Soriano, D.R. How globalization is changing digital technology adoption: An international perspective. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farida, I.; Setiawan, D. Business strategies and competitive advantage: The role of performance and innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudirjo, F. Marketing strategy in improving product competitiveness in the global market. J. Contemp. Adm. Manag. (ADMAN) 2023, 1, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncoro, W.; Suriani, W.O. Achieving sustainable competitive advantage through product innovation and market driving. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2018, 23, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrisno, S.; Ausat, A.M.A.; Permana, B.; Harahap, M.A.K. Do Information Technology and Human Resources Create Business Performance: A Review. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2023, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, A.; Grewal, R.; Sambamurthy, V. Information technology competencies, organizational agility, and firm performance: Enabling and facilitating roles. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 976–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrjoub, A.M.S.; Al Qudah, L.A.M.; Al Othman, L.N.; Bataineh, A.; Aburisheh, K.E.; Alkarabsheh, F. Information Technology and its Role in Improving the Quality of Financial Control due to Corona Pandemic: The Jordanian Income Tax as A Case Study. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2023, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanowska, A. Improving the competitiveness of enterprises through effective customer relationship management. Ekon. I Prawo. Econ. Law 2017, 16, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, P. The E-Commerce Investment and Enterprise Performance Based on Customer Relationship Management. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. (JGIM) 2022, 30, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmeta, R. Methodology for customer relationship management. J. Syst. Softw. 2006, 79, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čierna, H.; Sujová, E. Differentiated customer relationship management–a tool for increasing enterprise competitiveness. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2022, 30, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausat, A.M.A. The Application of Technology in the Age of COVID-19 and Its Effects on Performance. Apollo J. Tour. Bus. 2023, 1, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausat, A.M.A.; Suherlan, S. Obstacles and solutions of MSMEs in electronic commerce during COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Indonesia. BASKARA J. Bus. Entrep. 2021, 4, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeshref, Y.; Khwanda, H. Information Systems Effect on Enabling Knowledge Management. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2022, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausat, A.M.A.; Al Bana, T.; Gadzali, S.S. Basic capital of creative economy: The role of intellectual, social, cultural, and institutional capital. Apollo J. Tour. Bus. 2023, 1, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subagja, A.D.; Ausat, A.M.A.; Suherlan, S. The role of social media utilization and innovativeness on SMEs performance. J. IPTEKKOM (J. Ilmu Pengetah. Teknol. Inf.) 2022, 24, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, I.M.; Harahap, M.A.K.; Sari, D.M.; Sakinah, R.D.; Ausat, A.M.A. Understanding Social Media: Benefits of Social Media for Individuals. J. Pendidik. Tambusai 2023, 7, 2317–2322. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, W.Y.; Hong, P.H.K.; Teck, T.S. Small and Medium-Sized Businesses in Malaysia Can Look Forward to the Future of Co-Creation, a Literature Review. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2022, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopia, N.; Maryam, N.; Saiddah, V.; Gadzali, S.S.; Ausat, A.M.A. The Influence of Online Business on Consumer Purchasing in Yogya Grand Subang. J. Educ. 2023, 5, 10297–10301. [Google Scholar]

- Rustiawan, I.; Amory, J.D.S.; Kristanti, D. The importance of creativity in human resource management to achieve effective administration. J. Contemp. Adm. Manag. (ADMAN) 2023, 1, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susantinah, N.; Krishernawan, I. Human resource management (HRM) strategy in improving organisational innovation. J. Contemp. Adm. Manag. (ADMAN) 2023, 1, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryketeng, M.; Syachbrani, W. Optimising human resources capacity: Driving adoption of latest technology and driving business innovation amidst the dynamics of the digital era. J. Contemp. Adm. Manag. (ADMAN) 2023, 1, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustian, K.; Pohan, A.; Zen, A.; Wiwin, W.; Malik, A.J. Human resource management strategies in achieving competitive advantage in business administration. J. Contemp. Adm. Manag. (ADMAN) 2023, 1, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. The development and validation of the organisational innovativeness construct using confirmatory factor analysis. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2004, 7, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecfing and Interprefing Innovafion Data, 3rd ed.; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Damanpour, F.; Aravind, D. Organizational structure and innovation revisited: From organic to ambidextrous structure. In Handbook of Organizational Creativity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 483–513. [Google Scholar]

- Buttle, F.; Maklan, S. Customer Relationship Management: Concepts and Technologies; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alrubaiee, L.; Al-Nazer, N. Investigate the impact of relationship marketing orientation on customer loyalty: The customer’s perspective. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2010, 2, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, W.T.; Benito, Ó.G. CRM software success: A proposed performance measurement scale. J. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 19, 856–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitz, J. The Roi of Human Capital: Measuring the Economic Value of Employee Performance; Amacom: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ologunde, A.O.; Monday, J.U.; James-Unam, F.C. The impact of strategic human resource management on competitiveness of small and medium-scale enterprises in the Nigerian hospitality industry. Afr. Res. Rev. 2015, 9, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máchová, R.; Volejníková, J.; Lněnička, M. Impact of e-government development on the level of corruption: Measuring the effects of related indices in time and dimensions. Rev. Econ. Perspect. 2018, 18, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, H.; Von Krogh, G.; Spaeth, S. How constraints and knowledge impact open innovation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1134–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr-Wisniewski, P.; Lu, Y. When more is too much: Operationalizing technology overload and exploring its impact on knowledge worker productivity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.; Salazar, I.; Vargas, P. Does information technology improve open innovation performance? An examination of manufacturers in Spain. Inf. Syst. Res. 2017, 28, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turulja, L.; Bajgorić, N. Innovation and information technology capability as antecedents of firms’ success. Interdiscip. Descr. Complex Syst. INDECS 2016, 14, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Nevo, S.; Jin, J.; Wang, L.; Chow, W.S. IT capability and organizational performance: The roles of business process agility and environmental factors. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Wu, F. Technological capability, strategic flexibility, and product innovation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, M.R.; Atlasi, R.; Ziapour, A.; Abbas, J.; Naemi, R. Innovative human resource management strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic narrative review approach. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Nguyen, B.; Chen, Y. Internet of things capability and alliance: Entrepreneurial orientation, market orientation and product and process innovation. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 402–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sin, L.Y.; Tse, A.C.; Yim, F.H. CRM: Conceptualization and scale development. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 1264–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmad, Z.; Hijazi, E.; Bazargan, A. The role of attention to human resources management measures in improving the performance of agricultural production cooperatives in Gilan province. Res. Method Behav. Sci. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, N.A.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Vorhies, D.W. Export marketing strategy implementation, export marketing capabilities, and export venture performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 271–289. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y. The relationship between HRM, technology innovation and performance in China. Int. J. Manpow. 2006, 27, 679–697. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.; Fidell, L.; Ullman, J. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: London, UK, 2019; Volume 5, pp. 544–561. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. (IJEC) 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: A guide for non-statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, A.T. Effects of innovation types on performance of manufacturing firms in Turkey. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Sub-Dimension | Code | Item | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Technology (IT) | CRM | IT1 | The company provides customized services/products for key customers. | [69,70]; |

| IT2 | Customer needs are identified through IT-based systems. | |||

| IT3 | Software systems have been implemented for sales and service processes. | |||

| IT4 | IT systems are used to improve customer loyalty. | |||

| IT5 | Customer information is collected through IT tools (systems/software). | |||

| HRM | IT6 | Using software provides accurate information for daily decisions. | ||

| IT7 | Digital automation systems are used to automate administrative tasks. | |||

| IT8 | Organizational IT systems are well-known to employees. | |||

| IT9 | Communication with managers and other departments occurs through IT systems. | |||

| IT10 | The company supports having IT specialists to solve technical issues. | |||

| Competitiveness (CP) | Competition | CP1 | The company faces strong local (domestic) competition. | [25,71] |

| CP2 | Market prices for the company’s products are high. | |||

| CP3 | Foreign (international) competition is fierce for the company. | |||

| Operations & Strategy | CP4 | On-time delivery of products/services is emphasized. | ||

| CP5 | A system has been developed to support marketing activities. | |||

| CP6 | A knowledge-based system is designed to understand international markets. | |||

| CP7 | Improving production process skills is emphasized. | |||

| Supply Chain | CP8 | We emphasize the use of high-quality materials from local suppliers. | ||

| CP9 | Cooperation with suppliers in product design is emphasized. | |||

| CP10 | Local suppliers are being controlled by the company. | |||

| CP11 | It is important for suppliers to deliver products on time. | |||

| Innovation Performance (IP) | Employee Training | IP1 | The company has invested in employee training in recent years. | [72] |

| IP2 | The company emphasizes professional employee development. | |||

| IP3 | Employees are encouraged to learn systematically and through practice. | |||

| Financial Rewards | IP4 | The company has increased financial rewards for employees. | ||

| IP5 | The company provides economic benefit opportunities for employees. | |||

| IP6 | The company assures employees’ families regarding future income. | |||

| Non-financial Rewards | IP7 | Employees can gain social acceptance, respect, and esteem in the company. | ||

| IP8 | Employees have opportunities to take innovation challenges. | |||

| IP9 | Employees have opportunities for personal development. | |||

| IP10 | Mistakes during innovation processes are not blamed. | |||

| IP11 | Employees and leaders are highly trusted. | |||

| IP12 | Among coworkers, the company promotes kindness. | |||

| Technical Innovation | IP13 | New ideas are regularly introduced into the production process. | ||

| IP14 | R&D cycles for new products are shorter. | |||

| IP15 | Significant improvements occur in company technology. | |||

| IP16 | Production equipment is frequently updated. |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability Coefficient | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.902 | 0.858 | 0.746 | |

| Components | Questions | Cronbach’s Alpha | Factor Analysis |

| Information Technology | 10 | 0.899 | 0.872–0.941 |

| Customer relation management | 5 | 0.907 | 0.869–0.964 |

| Human resources management | 5 | 0.891 | 0.879–0.997 |

| Competitiveness | 11 | 0.928 | 0.750–0.934 |

| Competition | 4 | 0.911 | 0.874–0.972 |

| Company operations and strategy | 3 | 0.936 | 0.762–0.974 |

| Supply chain | 4 | 0.939 | 0.883–0.924 |

| Innovative performance | 16 | 0.872 | 0.812–0.910 |

| Staff training | 3 | 0.938 | 0.772–0.974 |

| Rewards and financial incentives | 3 | 0.889 | 0.835–0.917 |

| Non-financial rewards and incentives | 6 | 0.902 | 0.693–0.914 |

| Technical innovation | 4 | 0.715 | 0.685–0.857 |

| Tip | Nip | Wip | Cip | Ip | SCH | OSMC | PC | CP | Hrm | Crm | IT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IT | 1 | |||||||||||

| Crm | 1 | 0.866 *** | ||||||||||

| Hrm | 1 | 0.510 *** | 0.872 *** | |||||||||

| CP | 1 | 0.346 *** | 0.325 *** | 0.386 *** | ||||||||

| PC | 1 | 0.716 *** | 0.310 *** | 0.271 *** | 0.335 *** | |||||||

| OSMC | 1 | 0.380 *** | 0.776 *** | 0.346 *** | 0.312 *** | 0.379 *** | ||||||

| SCH | 1 | 0.326 *** | 0.226 *** | 0.713 *** | 0.113 | 0.137 * | 0.144 * | |||||

| Ip | 1 | 0.157 ** | 0.443 *** | 0.278 *** | 0.397 *** | 0.307 *** | 0.300 *** | 0.349 *** | ||||

| CIp | 1 | 0.798 *** | 0.179 ** | 0.361 *** | 0.265 *** | 0.365 *** | 0.344 *** | 0.294 *** | 0.367 *** | |||

| Wip | 1 | 0.556 *** | 0.836 *** | 0.103 | 0.332 *** | 0.211 *** | 0.292 *** | 0.158 ** | 0.109 | 0.154 ** | ||

| Nip | 1 | 0.592 *** | 0.488 *** | 0.795 *** | 0.079 | 0.241 *** | 0.189 ** | 0.230 *** | 0.219 *** | 0.213 *** | 0.249 *** | |

| Tip | 1 | 0.464 *** | 0.447 *** | 0.338 *** | 0.690 *** | 0.115 | 0.451 *** | 0.188 ** | 0.342 *** | 0.217 *** | 0.326 *** | 0.312 *** |

| Variables | p-Value | Variables | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tr | 0.925 | Nip | 0.946 |

| Crm | 0.948 | Tip | 0.913 |

| Hrm | 0.732 | ||

| CP | 0.902 | ||

| Ccm | 0.98 | ||

| OSMC | 0.976 | ||

| SCH | 0.713 | ||

| Wip | 0.613 |

| Sum of Roots | Mean of Roots | Degree of Freedom | Statistic | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of information technology on small and medium enterprises’ competitiveness | 1.400 | 1.400 | 1 | 0.680 | 0.409 |

| Innovative performance of small and medium enterprises as a result of information technology | 2.170 | 2.170 | 1 | 0.550 | 0.415 |

| Information technology and competitiveness are mediated by innovative performance | 10.223 | 10.223 | 1 | 0.621 | 0.783 |

| Hypotheses | Source | Sum of Roots | Mean of Roots | F Statistic | Df | Significance | OTA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of information technology on small and medium enterprises’ competitiveness | Pre-test*error group | 41.942 | 1.023 | 0.822 | 1 | 0.684 | 0.130 |

| 9.114 | 1.224 | ||||||

| Innovative performance of small and medium enterprises as a result of information technology | Pre-test*error group | 13.556 | 0.019 | 0.740 | 1 | 0.755 | 0.090 |

| 13.358 | 0.019 | ||||||

| Information technology and competitiveness are mediated by innovative performance | Pre-test*error group | 31.117 | 0.724 | 0.900 | 1 | 0.638 | 0.130 |

| 46.169 | 0.804 |

| Hypotheses | Sum of Roots | Mean of Roots | F Statistic | Degree of Freedom | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of information technology on small and medium enterprises’ competitiveness | 3.689 | 3.689 | 2.169 | 1 | 0.004 |

| The impact of information technology on the innovative performance of small and medium enterprises | 6.752 | 6.752 | 9.400 | 1 | 0.000 |

| Innovative performance of small and medium enterprises as a result of information technology | 4.580 | 4.580 | 4.580 | 1 | 0.047 |

| Variable | Medium Firms | Small Firms | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP Model | CP Model | IP Model | CP Model | |

| Coefficient | Coefficient | Coefficient | Coefficient | |

| IT | 0.329 *** | 0.199 ** | 0.143 * | 0.314 *** |

| CP | 0.215 * | 0.253 ** | 0.291 *** | 0.190 * |

| Gender | 0.137 | –0.027 | –0.086 | –0.220 |

| Experience | –0.009 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.038 |

| Age | –0.057 | 0.065 | –0.065 | 0.046 |

| Education | 0.065 | –0.011 | 0.044 | –0.011 |

| Constant | 0.904 ** | 1.799 *** | 0.894 * | 1.107 ** |

| Small Firms | Medium Firms | |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 1 |

| Coefficient | Coefficient | |

| IT | 0.222 *** | 0.164 * |

| IP | 0.199 ** | 0.117 |

| IT*IP | 0.068 *** | 0.235 |

| CP | 0.141 * | 0.235 * |

| Gender | –0.052 | 0.112 |

| Experience | –0.012 | –0.004 |

| Company Type | 0.042 | –0.046 |

| Age | 0.029 | 0.07 |

| Education | 0.008 | 1.694 |

| Constant | 1.267 *** | 0.235 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

ArminKia, A.; Moradi, M.; Salehi, M. The Relationship Between Information Technology Dimensions and Competitiveness Dimensions of SMEs Mediated by the Role of Innovative Performance. Information 2025, 16, 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121100

ArminKia A, Moradi M, Salehi M. The Relationship Between Information Technology Dimensions and Competitiveness Dimensions of SMEs Mediated by the Role of Innovative Performance. Information. 2025; 16(12):1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121100

Chicago/Turabian StyleArminKia, AmirHossein, Mahdi Moradi, and Mahdi Salehi. 2025. "The Relationship Between Information Technology Dimensions and Competitiveness Dimensions of SMEs Mediated by the Role of Innovative Performance" Information 16, no. 12: 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121100

APA StyleArminKia, A., Moradi, M., & Salehi, M. (2025). The Relationship Between Information Technology Dimensions and Competitiveness Dimensions of SMEs Mediated by the Role of Innovative Performance. Information, 16(12), 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121100