Validating the Use of Natural Language Processing and Text Mining for Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs and Criminal Justice Articles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

NLP in Criminal Justice

3. The Current Study

4. Methodology

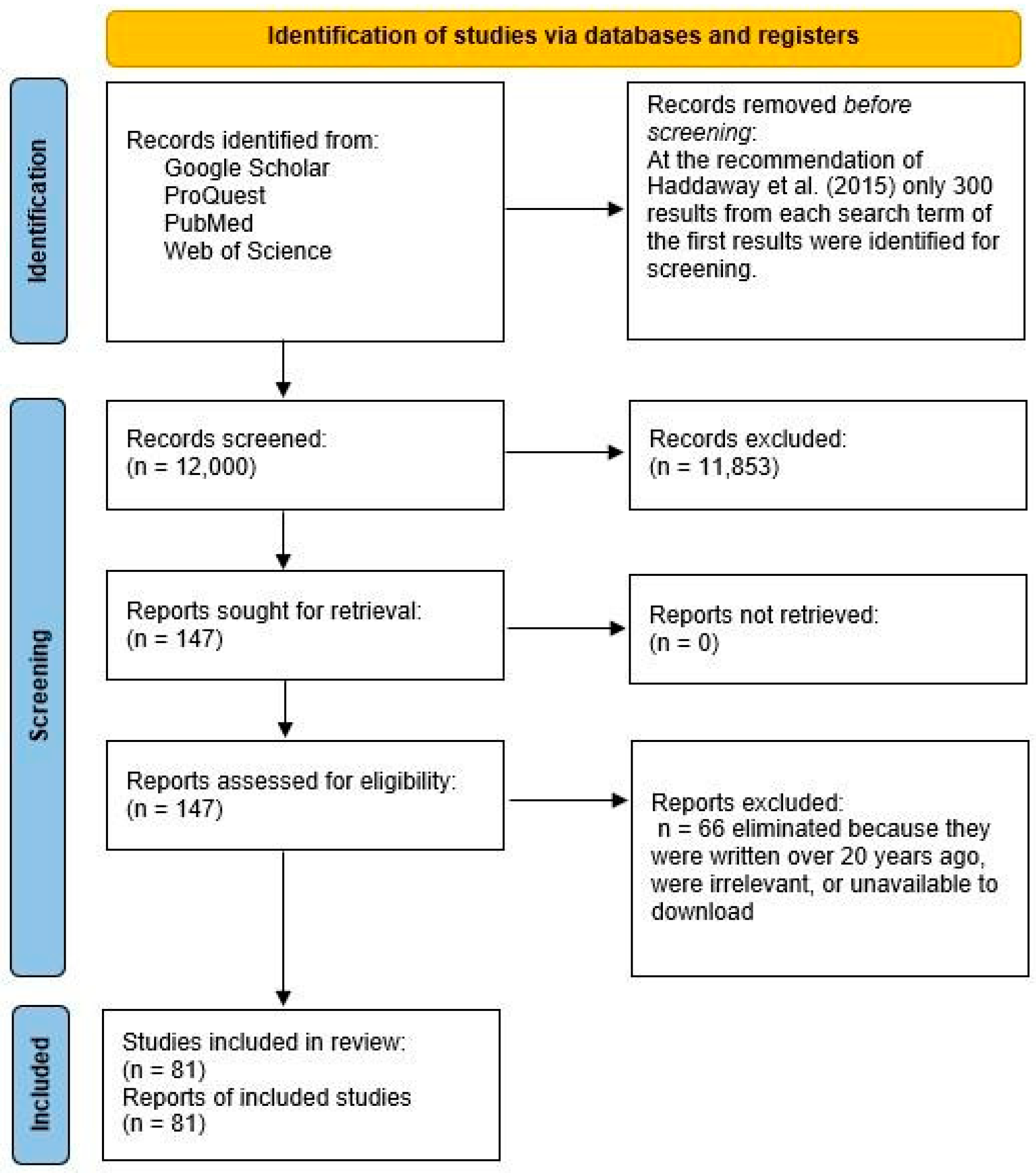

4.1. The Manual Search Process Conducted by the Domain Expert

4.2. NLP and Topic Modeling

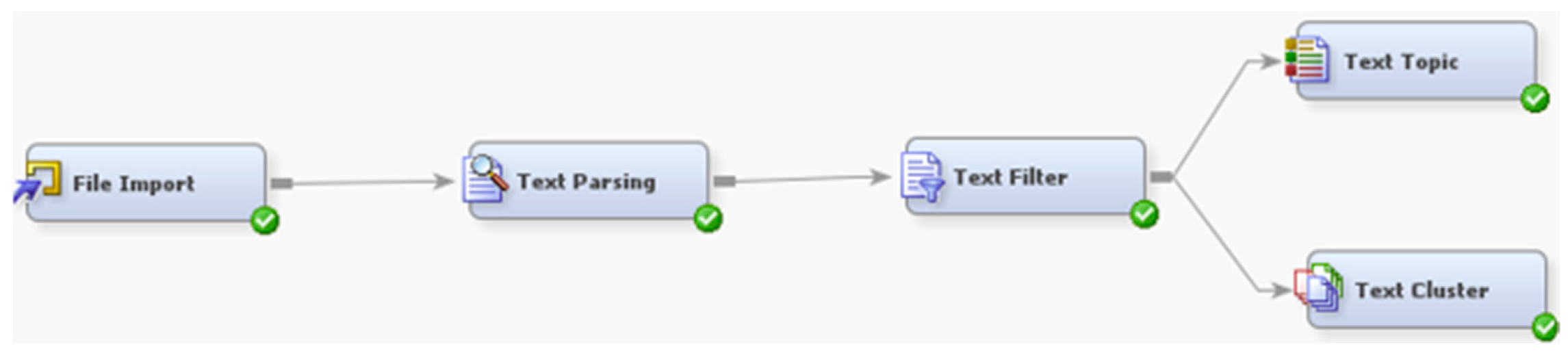

4.2.1. File Import

4.2.2. Text Parsing

4.2.3. Text Filtering (Text Filter)

4.2.4. Topic Modeling (Text Topic and Text Cluster)

4.2.5. Number of Topics

4.2.6. Highlighting Key Themes

- •

- Theme 1: Trauma and Reinjury—Trauma and reinjury-related topics are one of the major themes identified from the body of articles analysed in this study. A key goal of HVIPs is to assist in trauma-informed care that allows individuals to avoid reinjury through social assistance and clinical sessions intended to address the trauma incurred from their injury or previous trauma the patient may have experienced. Topics encompass key mental health-related ideas like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and symptoms related to the potential trauma incurred from these events. Document groups also consist of the key ideas of re-injury or “injury recidivism” (highlighted in Topic t5). These topics outline some of the more measurable outcomes of HVIPs, like rehospitalization and reinjury, wherein individuals may incur reinjury if their trauma is not sufficiently addressed. Identifying this theme allows for a further understanding of the public health goals and outcomes of HVIPs and where the criminal justice-related HVIP literature explores these topics.

- •

- Theme 2: Practitioners and Program Development—The second theme outlined in these topics is related to practitioner and program development. By gauging the repeated topics picked up from the corpus, this theme allows for a more thorough discussion of programmatic information, such as that regarding staff, managing clients, and case processing. Because of the hospital-based setting in which HVIPs are implemented, it is not surprising that a discussion of these ideas on practitioner and program development will be prevalent in the selected body of research.

- •

- Theme 3: Domestic and Gender-based Violence—The third theme highlights some of the key intersections between HVIPs and victimization, wherein it examines the topics of intimate partner violence (IPV), elder abuse, and domestic violence as it relates to service delivery. Identifying these topics in the corpus suggests the role that HVIPs play for women who are victims of violence, which is a population that is often challenging for service providers to reach [54,55]. Additionally, a unique set of topics in this theme consists of the consideration of elder abuse, which possibly explains where HVIPs can be leveraged to address issues of elder abuse. Elder abuse is a growing topic in criminal justice as researchers and practitioners have started to shed light on the unique needs and risks that the elderly population faces [56]. This review, therefore, identifies where trauma-informed hospital programs can be used to address the needs of these populations.

- •

- Theme 4: Violence and Victimization—The fourth and final theme that is present throughout the research includes the topics of violence and victims of violence. These topics briefly discuss the population affected by violence and victimisation as seen in Topic t3 (Table 3), with the repetition of men and black men specifically. Topics in this theme also appear to relate to gun violence (firearms) and possible avenues of violence prevention. HVIPs and HVIP services are oriented towards individuals who are victims of violence. The recurrent topics in this theme highlight the significance of the needs of clients and the importance of placing special attention on gun violence.

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| HAJC | Healthcare Approaches to Justice Collaborative |

| HVIP | Hospital-based Violence Intervention Program |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

References

- Gorman, E.; Coles, Z.; Baker, N.; Tufariello, A.; Edemba, D.; Ordonez, M.; Walling, P.M.; Livingston, D.H.M.; Bonne, S. Beyond recidivism: Hospital-based violence intervention and early health and social outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2022, 235, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.B., Jr.; Wical, W.; Kottage, N.; Bullock, C. Shook Ones: Understanding the Intersection of Nonfatal Violent Firearm Injury, Incarceration, and Traumatic Stress Among Young Black Men. Am. J. Men’s Health 2020, 14, 1557988320982181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affinati, S.; Patton, D.; Hansen, L.; Ranney, M.; Christmas, A.B.; Violano, P.; Sodhi, A.; Robinson, B.; Crandall, M.; from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Injury Control and Violence Prevention Section and Guidelines Section. Hospital-based violence intervention programs targeting adult populations: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma evidence-based review. Trauma Surg. Acute Care Open 2016, 1, e000024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, B.L.; Shipper, A.G.; Downton, K.D.; Lane, W.G. The effects of health care–based violence intervention programs on injury recidivism and costs: A systematic review. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016, 81, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio, F. The Procrustean Nature of AI and the Legal Implications of Its Use in the Criminal System Decision Making of Argentina. In Government Response to Disruptive Innovation: Perspectives and Examinations; Edwards, S., III, Masterson, J., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Završnik, A. Criminal justice, artificial intelligence systems, and human rights. In ERA Forum; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 20, pp. 567–583. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, A.A.; Kennedy, D.M. A Framework for Addressing Violence and Serious Crime: Focused Deterrence, Legitimacy, and Prevention; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, S.; Shah, A.K.; Strange, C.C.; Stillman, K. Hospital-based violence intervention: Strategies for cultivating internal support, community partnerships, and strengthening practitioner engagement. J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 2022, 14, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, S.; Neudecker, C.H.; Strange, C.C.; Wojcik, M.L.; Shah, A.; Solhkhah, R. Hospital-based violence intervention programs (HVIPs): Making a case for qualitative evaluation designs. Crime Delinq. 2023, 69, 487–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, S.; Dmello, J.R. Proposing a unified framework for coordinated community response. Violence Against Women 2022, 28, 1873–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.L.; Wright, J.L.; Markakis, D.; Copeland-Linder, N.; Menvielle, E. Randomized trial of a case management program for assault-injured youth: Impact on service utilization and risk for reinjury. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2008, 24, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Eslinger, D.M.; Stolley, P.D. Hospital-based violence intervention programs work. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2006, 61, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, C.E.; Jiang, D.; Logsetty, S.; Chernomas, W.; Mordoch, E.; Cochrane, C.; Mahmood, J.; Woodward, H.; Klassen, T.P. Feasibility and efficacy of a hospital-based violence intervention program on reducing repeat violent injury in youth: A randomized control trial. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 22, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatzick, D.; Russo, J.; Lord, S.P.; Varley, C.; Wang, J.; Berliner, L.; Jurkovich, G.; Whiteside, L.K.; O’Connor, S.; Rivara, F.P. Collaborative care intervention targeting violence risk behaviors, substance use, and posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms in injured adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014, 168, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurana, D.; Koli, A.; Khatter, K.; Singh, S. Natural language processing: State of the art, current trends and challenges. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 3713–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigano, C. Using artificial intelligence to address criminal justice needs. Natl. Inst. Justice J. 2019, 280, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, D.; Bagaric, M.; Stobbs, N. A Framework for the Efficient and Ethical Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Criminal Justice System. Fla. State Univ. Law Rev. 2019, 47, 749. [Google Scholar]

- Schnoebelen, T. Goal-oriented design for ethical machine learning and NLP. In Proceedings of the First ACL Workshop on Ethics in Natural Language Processing, Valencia, Spain, 4 April 2017; pp. 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, D.U.; Frey, W.R.; McGregor, K.A.; Lee, F.T.; McKeown, K.; Moss, E. Contextual analysis of social media: The promise and challenge of eliciting context in social media posts with natural language processing. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, New York, NY, USA, 7–9 February 2020; pp. 337–342. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, B.L.; Progovac, A.M.; Chen, P.; Mullin, B.; Hou, S.; Baca-Garcia, E. Novel Use of Natural Language Processing (NLP) to Predict Suicidal Ideation and Psychiatric Symptoms in a Text-Based Mental Health Intervention in Madrid. In Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, L.; Pokhilenko, I.; Drost, R.; Paulus, A.; Evers, S. Criminal Justice Costs And Benefits Of Mental Health Interventions. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2019, 35, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, D.; Zamora-Resendiz, R.; Beckham, J.C.; Kimbrel, N.A.; Oslin, D.W.; Tamang, S.; Crivelli, S.; Million Veteran Program Suicide Exemplar Work Group. A case for developing domain-specific vocabularies for extracting suicide factors from healthcare notes. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 151, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.T.; Socrates, V.; Gilson, A.; Safranek, C.; Chi, L.; Wang, E.; Puglisi, L.B.; Brandt, C.; Wang, K. Identifying Incarceration Status in the Electronic Health Record Using Natural Language Processing in Emergency Department Settings. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, B.G.; Sharma, M.M.; Vekaria, V.; Adekkanattu, P.; Patterson, O.V.; Glicksberg, B.; Lepow, L.A.; Ryu, E.; Biernacka, J.M.; Furmanchuk, A.; et al. Extracting social determinants of health from electronic health records using natural language processing: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 2021, 28, 2716–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.A.; Long, J.B.; McGinnis, K.A.; Wang, K.H.; Wildeman, C.J.; Kim, C.; Bucklen, K.B.; Fiellin, D.A.; Bates, J.; Brandt, C.; et al. Measuring exposure to incarceration using the electronic health record. Med. Care 2019, 57, S157–S163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colling, C.; Khondoker, M.; Patel, R.; Fok, M.; Harland, R.; Broadbent, M.; McCrone, P.; Stewart, R. Predicting high-cost care in a mental health setting. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gichoya, J.W.; McCoy, L.G.; Celi, L.A.; Ghassemi, M. Equity in essence: A call for operationalising fairness in machine learning for healthcare. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2021, 28, e100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maël, L.E. Terminology development for Digital Forensics using Natural Language Processing. Master’s Thesis, University of Dundee, Dundee, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, R.D.; Mancini, K.; Abram, M.D. Natural Language Processing Enhanced Qualitative Methods: An Opportunity to Improve Health Outcomes. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231214144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, D.; Forkan, A.R.M.; Kang, Y.B.; Trounson, J.; Anthony, T.; Marchetti, E.; Shepherd, S. Pre-sentence reports for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: An analysis of language and sentiment. Trends Issues Crime Crim. Justice 2022, 659, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mourtgos, S.M.; Adams, I.T. The rhetoric of de-policing: Evaluating open-ended survey responses from police officers with machine learning-based structural topic modeling. J. Crim. Justice 2019, 64, 101627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.A.; Ku, C.S. Identifying the Public’s Changing Concerns During a Global Health Crisis: Text Mining and Comparative Analysis of Tweets During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In International Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking and Parallel/Distributed Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- McCosker, A.; Farmer, J.; Soltani Panah, A. Community Responses to Family Violence: Charting Policy Outcomes Using Novel Data Sources, Text Mining and Topic Modelling; Swinburne University of Technology: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goin, D.E.; Rudolph, K.E.; Ahern, J. Predictors of firearm violence in urban communities: A machine-learning approach. Health Place 2018, 51, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahri, Z.; Shuhidan, S.M.; Sanusi, Z.M. An ontology-based representation of the financial criminology domain using text analytics processing. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2018, 18, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Pina-Sánchez, J.; Grech, D.; Brunton-Smith, I.; Sferopoulos, D. Exploring the origin of sentencing disparities in the Crown Court: Using text mining techniques to differentiate between court and judge disparities. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 84, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adily, A.; Karystianis, G.; Butler, T. Text mining police narratives to identify types of abuse and victim injuries in family and domestic violence events. Trends Issues Crime Crim. Justice 2021, 630, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A.; Young, A.T.; Liang, A.S.; Gonzales, R.; Douglas, V.C.; Hadley, D. Development and validation of an electronic health record–based machine learning model to estimate delirium risk in newly hospitalized patients without known cognitive impairment. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e181018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Chiam, Y.K.; Lo, S.K. Text-mining techniques and tools for systematic literature reviews: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 24th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference, Nanjing, China, 4–8 December 2017; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- van Dinter, R.; Tekinerdogan, B.; Catal, C. Automation of systematic literature reviews: A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2021, 136, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, C.F. Cheap, Quick, and Rigorous: Artificial Intelligence and the Systematic Literature Review. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2023, 42, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre-López, J.; Ramírez, A.; Romero, J.R. Artificial intelligence to automate the systematic review of scientific literature. Computing 2023, 105, 2171–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthcare Approaches to Justice Collaborative, Montclair State University. HAJC. Available online: https://www.montclair.edu/chss/about-the-college/chss-initiatives/healthcare-approaches-to-justice-collaborative/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Haddaway, N.R.; Collins, A.M.; Coughlin, D.; Kirk, S. The Role of Google Scholar in Evidence Reviews and Its Applicability to Grey Literature Searching; NIH: National Library of Medicine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, S.; Klein, E.; Loper, E. Natural Language Processing with Python: Analyzing Text with the Natural Language Toolkit; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Demsar, J.; Curk, T.; Erjavec, A.; Gorup, C.; Hocevar, T.; Milutinovic, M.; Mozina, M.; Polajnar, M.; Toplak, M.; Staric, A.; et al. Orange: Data Mining Toolbox in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2013, 14, 2349–2353. [Google Scholar]

- Ertek, G.; Tapucu, D.; Arin, I. Text Mining with RapidMiner Chapter. In RapidMiner: Data Mining Use Cases and Business Analytics Applications, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, E.; Hall, M.A.; Witten, I.H. The WEKA Workbench. In Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques, 4th ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Matignon, R. Data Mining Using SAS® Enterprise Miner; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS® Enterprise Miner 15.2: Reference Help; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS® Text Miner 15.2: Reference Help; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, G.; Pagolu, M.; Garla, S. Text Mining and Analysis: Practical Methods, Examples, and Case Studies Using SAS®; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, M.; Valentine, J.M.; Son, J.B.; Muhammad, M. Intimate Partner Violence and Barriers to Mental Health Care for Ethnically Diverse Populations of Women. Trauma Violence Abus. 2009, 10, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.L.; Uthman, C.; Nichols-Hadeed, C.; Kruchten, R.; Thompson Stone, J.; Cerulli, C. Mental health therapists’ perceived barriers to addressing intimate partner violence and suicide: Families, Systems, & Health. Fam. Syst. Health 2021, 39, 188–197. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S.L. The shifting conceptualization of elder abuse in the United States: From social services, to criminal justice, and beyond. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackensack Meridian Health. Project HEAL. Available online: https://www.hackensackmeridianhealth.org/en/project-heal (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Okadome, T. Essentials of Generative AI; 2025th Edition; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. ChatGPT. Available online: https://chat.openai.com (accessed on 20 July 2025).

| Topic | Term Cutoff | Doc Cutoff | # of Terms | # of Docs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) ed, +youth, eds, +process, staff | 0.058 | 0.04 | 72 | 39 |

| (B) +cost, +cost, +estimate, +vip, different | 0.058 | 0.043 | 54 | 40 |

| (C) ipv, +woman, +provider, +partner, partner violence | 0.057 | 0.05 | 44 | 28 |

| (D) +manager, +client, +insight, +case, +relationship | 0.058 | 0.047 | 67 | 40 |

| (E) +justice system, +survivor, support, justice, +state | 0.058 | 0.035 | 79 | 35 |

| (F) +control, +group, treatment, reinjury, control group | 0.058 | 0.055 | 62 | 49 |

| (G) +vip, recidivism, injury recidivism, +associate, success | 0.058 | 0.048 | 68 | 36 |

| (H) elder, +old, abuse, +adult, inclusion | 0.057 | 0.049 | 52 | 34 |

| (I) ptsd, prevalence, pediatric, psychological, +score | 0.058 | 0.047 | 71 | 53 |

| (J) hvips, hvip, +barrier, existing, +literature | 0.058 | 0.044 | 63 | 44 |

| (K) +firearm, +firearm injury, +assault, +hospital, patient | 0.058 | 0.041 | 63 | 44 |

| (L) +youth, +attitude, +gun, +state, awareness | 0.058 | 0.043 | 61 | 43 |

| (M) +survivor, domestic, +service, +referral, abuse | 0.058 | 0.051 | 70 | 55 |

| (N) gang, +client, success, +goal, interpersonal violence | 0.058 | 0.036 | 77 | 35 |

| (O) +client, penetrating, +woman, +wound, stab | 0.058 | 0.046 | 74 | 53 |

| (P) +man, black, +young, black, +black man | 0.058 | 0.051 | 64 | 42 |

| Topic | Term Cutoff | Doc Cutoff | # of Terms | # of Docs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (t1) +control, +group, reinjury, repeat, treatment | 0.058 | 0.056 | 66 | 46 |

| (t2) ipv, +woman, +provider, +partner, partner violence | 0.058 | 0.048 | 47 | 29 |

| (t3) +young, black, +man, +male, +violent injury | 0.058 | 0.049 | 56 | 38 |

| (t4) +manager, +client, +case, +insight, +relationship | 0.058 | 0.044 | 60 | 40 |

| (t5) +vip, recidivism, +cost, injury recidivism, +cost | 0.058 | 0.045 | 62 | 38 |

| (t6) elder, abuse, +old, +adult, inclusion | 0.057 | 0.049 | 49 | 38 |

| (t7) +youth, +gun, +attitude, prevention, awareness | 0.058 | 0.042 | 61 | 41 |

| (t8) ed, +youth, eds, +process, staff | 0.058 | 0.043 | 80 | 46 |

| (t9) +firearm, +client, +firearm injury, +assault, +victim | 0.058 | 0.048 | 81 | 48 |

| (t10) hvips, ptsd, +practice, +symptom, mental health | 0.058 | 0.045 | 76 | 48 |

| (t11) +survivor, domestic, +referral, +service, domestic violence | 0.058 | 0.05 | 66 | 55 |

| Topic | 4 Themes | 2 Themes |

|---|---|---|

| (t1) +control, +group, reinjury, repeat, treatment | Trauma and Reinjury | Public Health |

| (t10) hvips, ptsd, +practice, +symptom, mental health | ||

| (t5) +vip, recidivism, +cost, injury recidivism, +cost | ||

| (t4) +manager, +client, +case, +insight, +relationship | Practitioner and Program Development | |

| (t8) ed, +youth, eds, +process, staff | ||

| (t2) ipv, +woman, +provider, +partner, partner violence | Domestic and Gender-based Violence | Criminal Justice |

| (t6) elder, abuse, +old, +adult, inclusion | ||

| (t11)+survivor, domestic, +referral, +service, domestic violence | ||

| (t3) +young, black, +man, +male, +violent injury | Violence and Victimization | |

| (t7) +youth, +gun, +attitude, prevention, awareness | ||

| (t9) +firearm, +client, +firearm injury, +assault, +victim |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ku, C.S.; Pugliese, K.; Dmello, J.R.; Peltier, M.R.; Green, R.; Ranjan, S. Validating the Use of Natural Language Processing and Text Mining for Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs and Criminal Justice Articles. Information 2025, 16, 1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121098

Ku CS, Pugliese K, Dmello JR, Peltier MR, Green R, Ranjan S. Validating the Use of Natural Language Processing and Text Mining for Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs and Criminal Justice Articles. Information. 2025; 16(12):1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121098

Chicago/Turabian StyleKu, Cyril S., Katheryne Pugliese, Jared R. Dmello, Morgan R. Peltier, Robert Green, and Sheetal Ranjan. 2025. "Validating the Use of Natural Language Processing and Text Mining for Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs and Criminal Justice Articles" Information 16, no. 12: 1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121098

APA StyleKu, C. S., Pugliese, K., Dmello, J. R., Peltier, M. R., Green, R., & Ranjan, S. (2025). Validating the Use of Natural Language Processing and Text Mining for Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs and Criminal Justice Articles. Information, 16(12), 1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121098