Client-Attentive Personalized Federated Learning for AR-Assisted Information Push in Power Emergency Maintenance

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Algorithmic Contribution: We propose the Client-Attentive Personalized Federated Learning (PFAA) algorithm tailored for highly heterogeneous industrial environments. By designing a novel Attention Network, PFAA moves beyond sample-size-based aggregation. It dynamically calculates attention scores by analyzing the correlation between local updates and the global optimization direction, theoretically reducing the weight divergence caused by Non-IID data distributions.

- Feature Representation Innovation: We introduce “Device Health Fingerprints” as a privacy-preserving semantic embedding. Unlike traditional FL which only transmits gradients, our method utilizes these lightweight fingerprints as auxiliary metadata to guide the server’s attention mechanism. This ensures that clients capturing rare fault patterns are assigned higher aggregation weights, improving the global model’s sensitivity to critical failures.

- System Integration & Validation: We implement a complete “cloud-edge-end” collaborative framework specifically for AR-assisted information push. This architecture validates the PFAA algorithm in a realistic industrial workflow, demonstrating significant improvements in task completion rates and decision adoption compared to rule-based and standard FL baselines.

2. Related Work

2.1. Applications of AR in Industrial Maintenance

2.2. Federated Learning and Its Applications in Industrial Fields

2.3. Power Maintenance Information Push Technology

3. Information Push Method

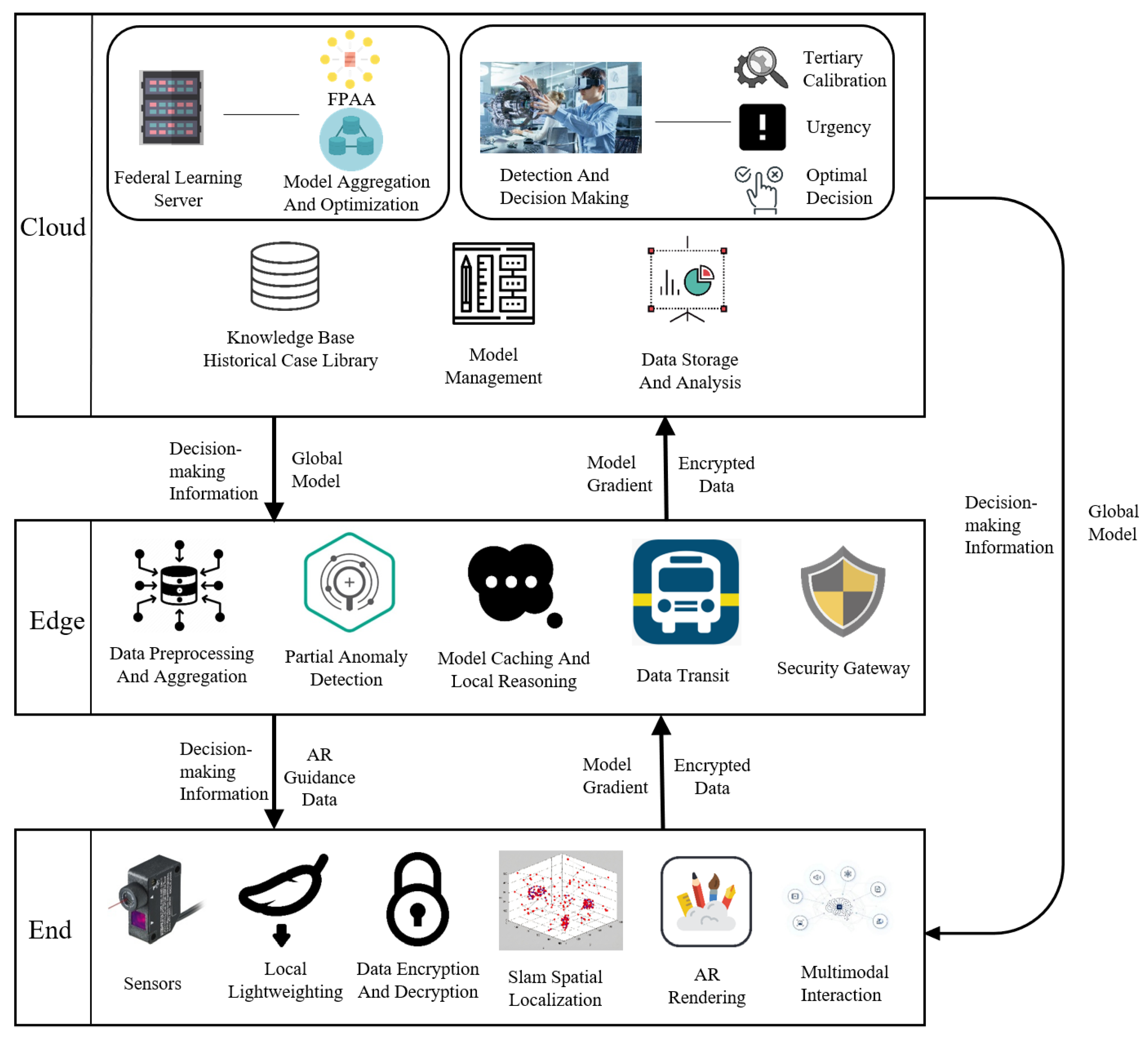

3.1. System Architecture

3.1.1. AR Terminal Layer

3.1.2. Edge Layer

3.1.3. Cloud Layer

3.1.4. Inter-Layer Coordination and Security Mechanism

3.2. Client-Attentive Personalized Federated Learning

3.2.1. Algorithm Description

3.2.2. Intelligent Fault Diagnosis and Decision-Making Based on PFAA

3.3. Collaborative Workflow and Precise Information Push Methods

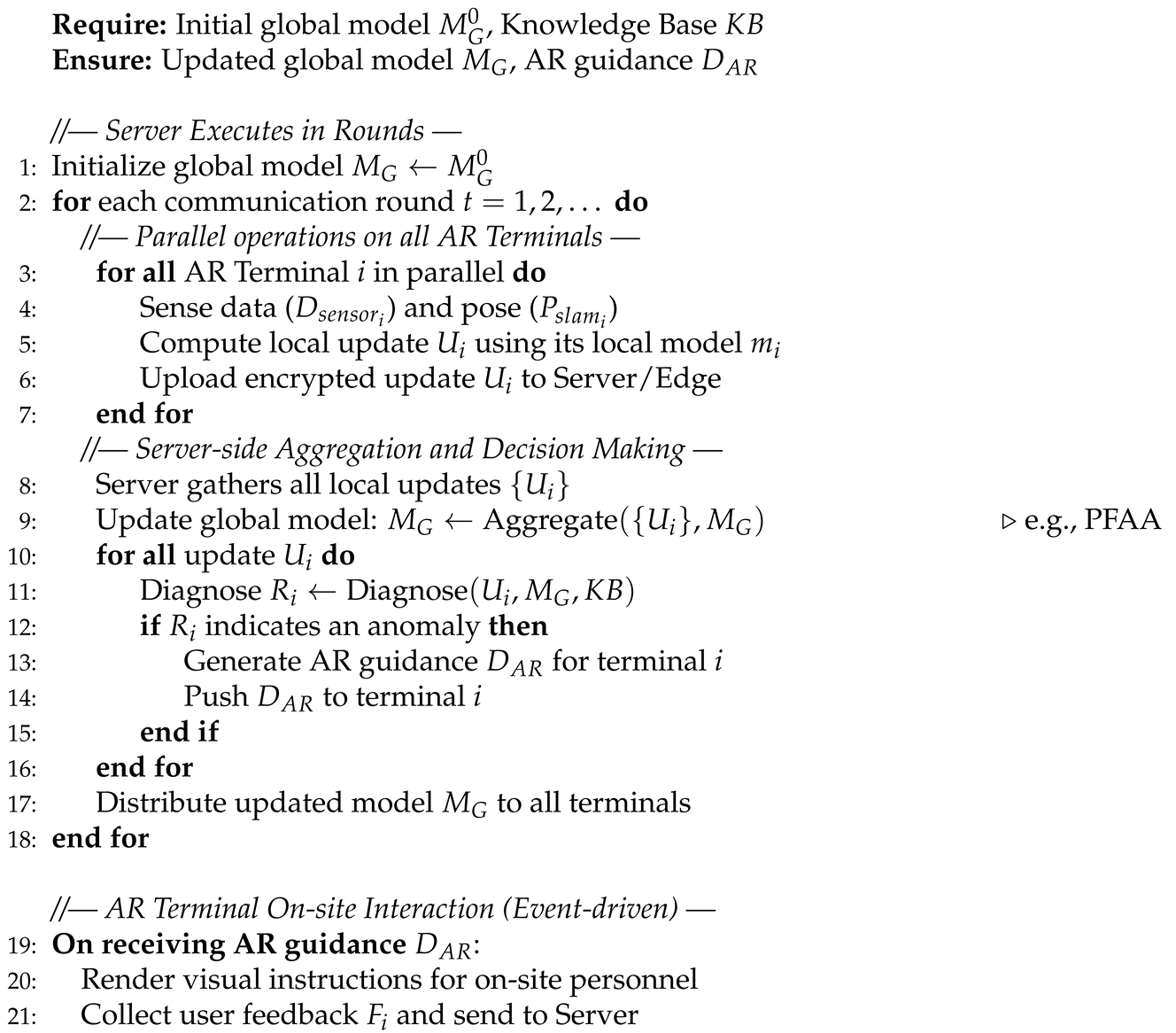

| Algorithm 1:Precise Information Push Algorithm for Power Emergency maintenance |

|

4. Experiment and Result Analysis

4.1. Experimental Setup

- Overall Scenario Setting: The experiment will be conducted in a simulated power emergency maintenance scenario. This scenario includes typical power equipment such as transformers and switchgear, as well as sensor networks, reproducing the three-tier system architecture proposed in this paper.

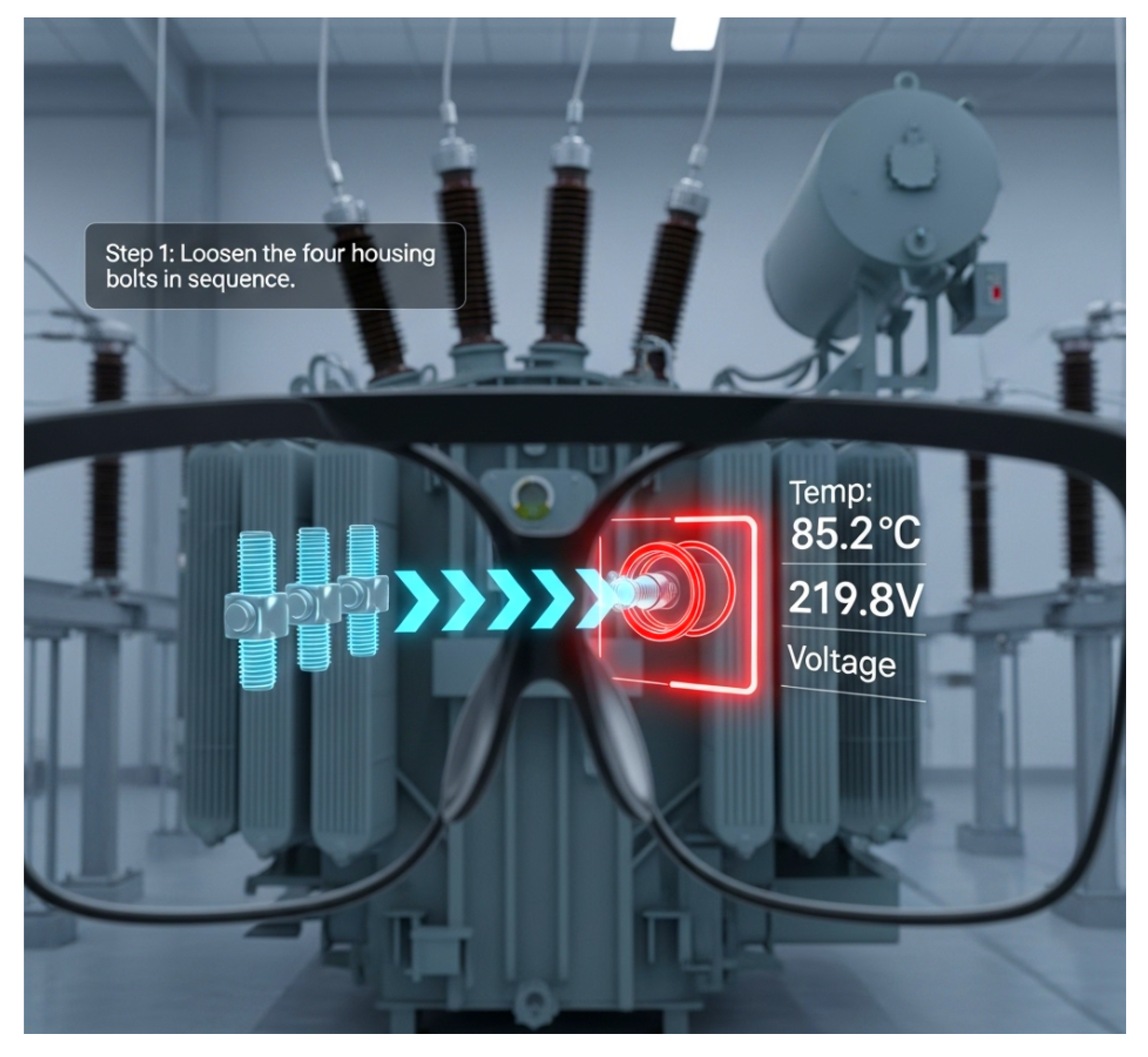

- AR Terminal Layer Simulation: For hardware, devices functionally comparable to mainstream AR glasses will be used to simulate data collection, local model execution, and information overlay display. For software, the Android system will be used, and Unity (C#) and Unreal Engine (C++) will be utilized for AR application development.

- Edge Layer Simulation: For hardware, distributed nodes will be built using edge computing devices such as NVIDIA Jetson series development boards, deployed near the simulated site to achieve low-latency data interaction. For software, the edge layer will run Linux (Ubuntu), using Python (Version 3.11.6) and libraries like Pandas and NumPy for data processing, and PyTorch (Version 2.1.1) for model inference.

- Cloud Server Simulation: For hardware, high-performance cloud server instances (AWS EC2) will be adopted, configured with multi-core CPUs, high-performance GPUs, and ample memory and storage. The software stack will include Linux (Ubuntu) operating systems, deep learning frameworks such as PyTorch for training global models, and databases like MySQL for storing various types of data.

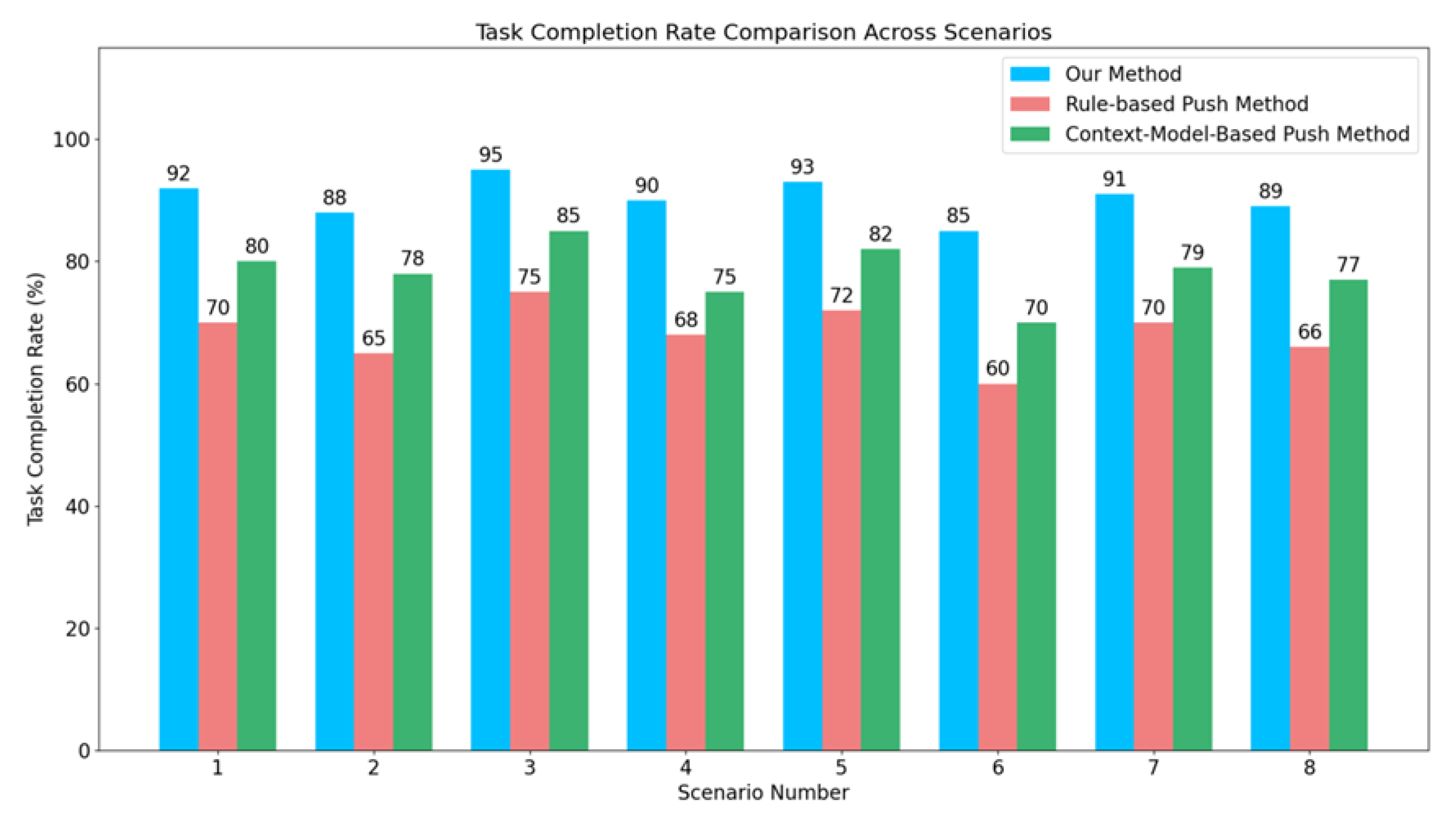

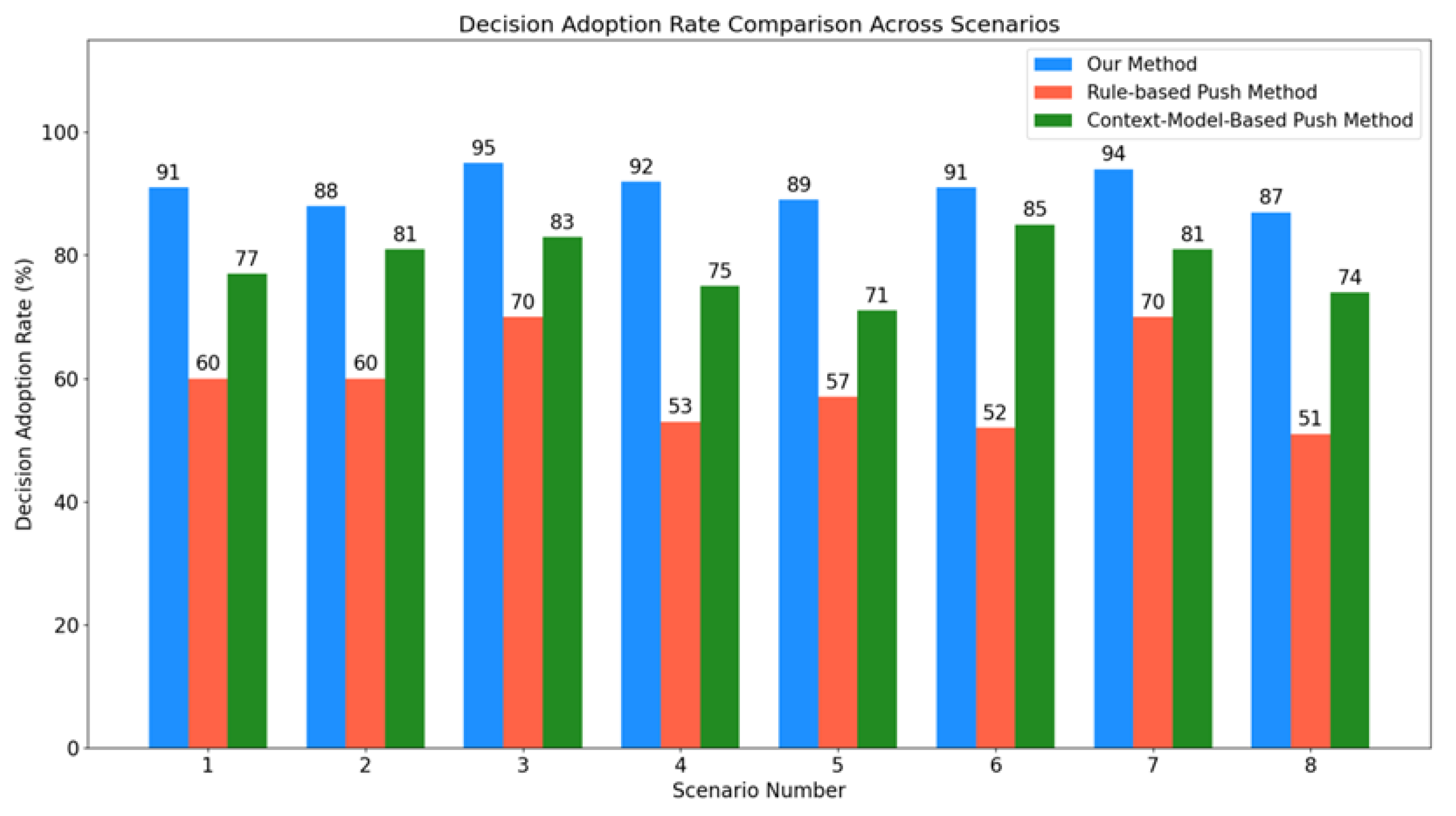

- Maintenance Decision and Guidance Effectiveness: This dimension focuses on the actual application effectiveness of system-generated maintenance decision information and AR guidance.Task Completion Rate (): Measures the proportion of maintenance personnel who successfully complete their pre-scheduled maintenance tasks with the assistance of AR guidance. Its calculation formula iswhere represents the number of successfully completed tasks, and represents the total number of tasks attempted.Decision Adoption Rate (): Measures the proportion of operational decisions or solutions recommended by the system that are actually adopted and executed by operations personnel. Its calculation formula iswhere represents the number of adopted decisions, and represents the total number of decisions recommended by the system.

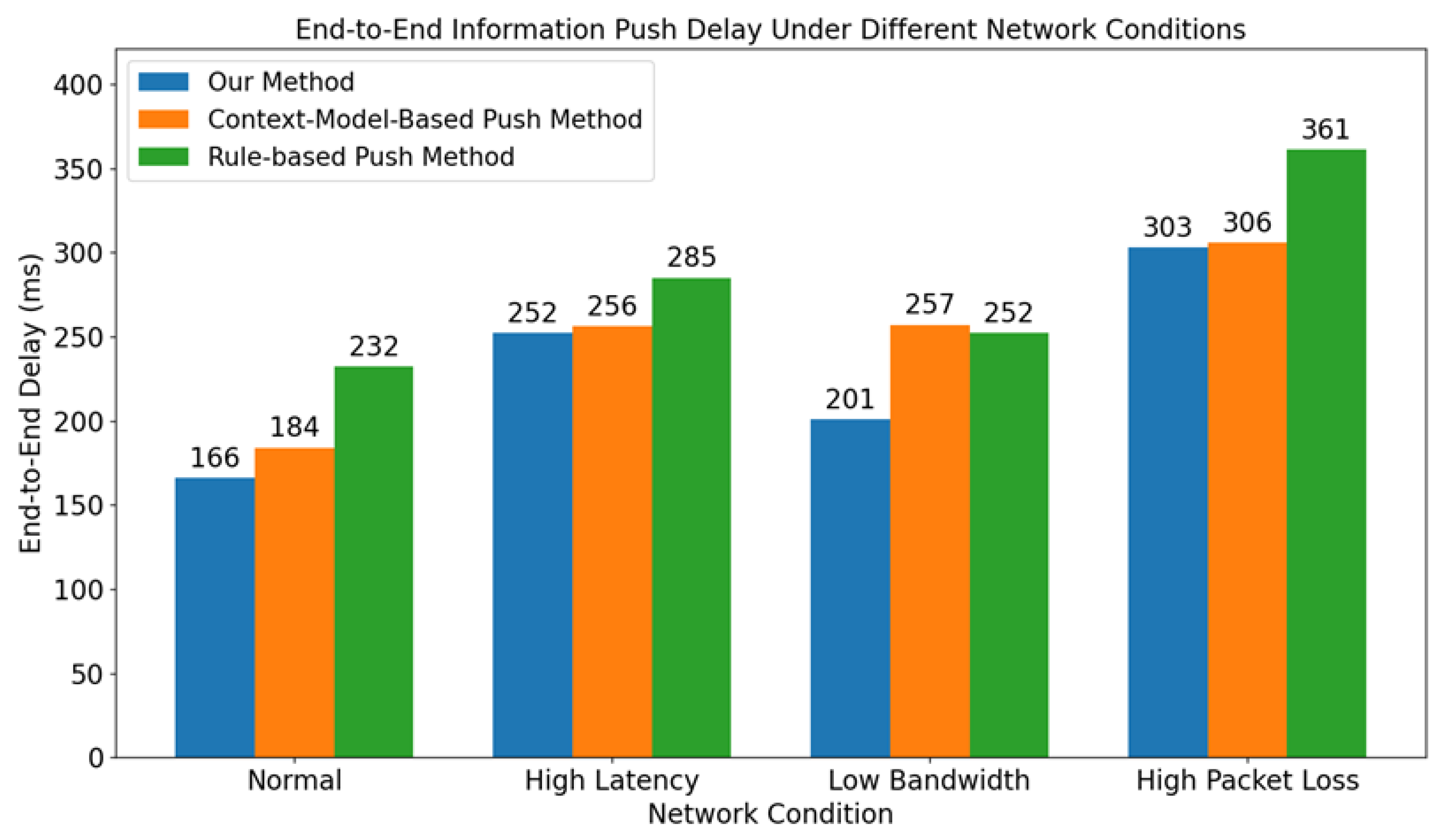

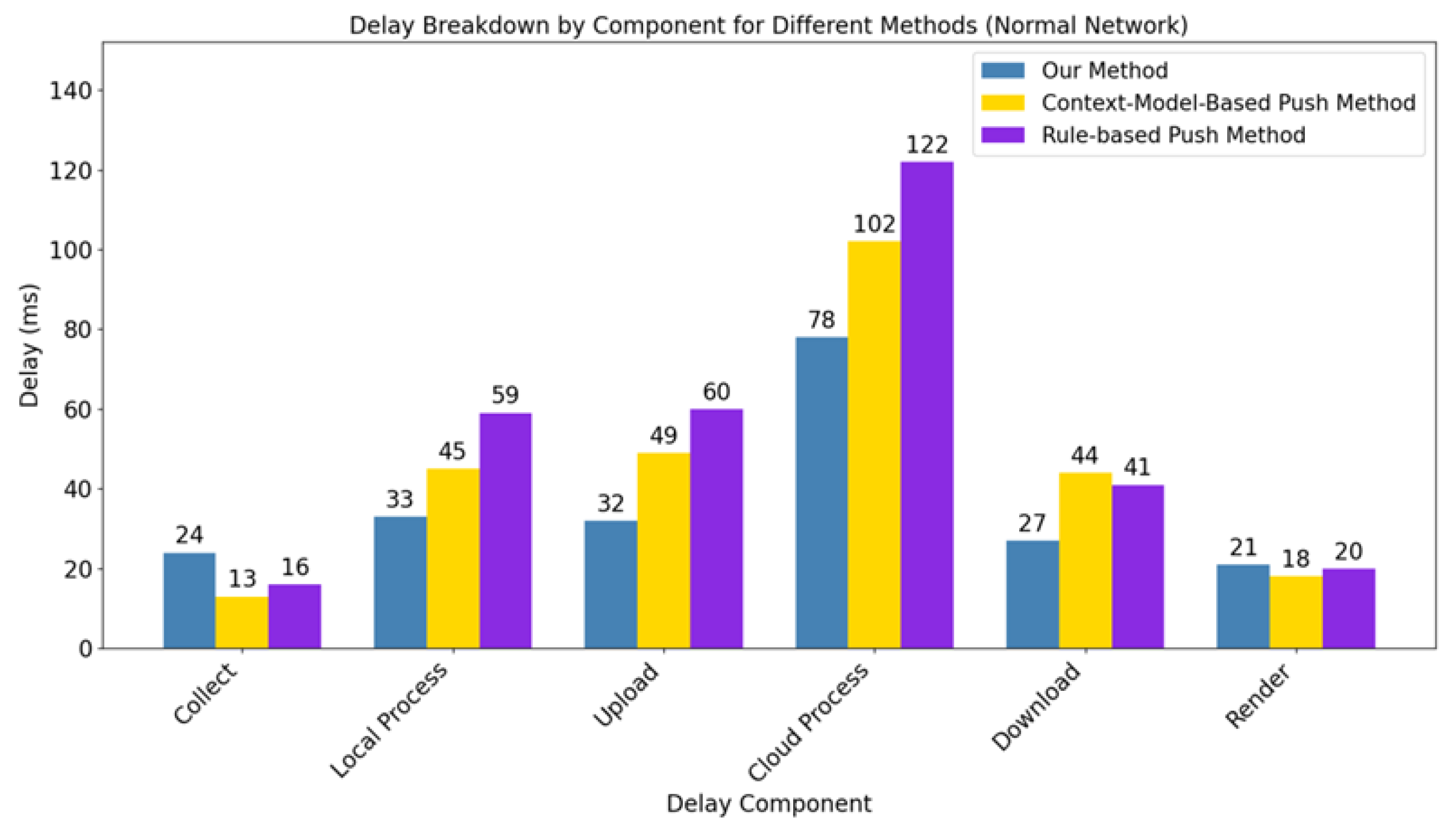

- Information push latency: For this, we will precisely measure the total time elapsed from the moment the AR terminal begins collecting device operating status data () until the final AR guidance information is successfully displayed on the AR terminal screen (). This total time will comprehensively cover the entire information processing and transmission chain. Its calculation formula can be expressed asFurthermore, this total delay can be decomposed into the sum of delays of each key link:where represents data collection time, represents AR terminal local preliminary processing time, represents data upload time, represents cloud server decision making time, represents the time for decision information to be transmitted back to the AR terminal, and represents the time for the AR device to complete rendering and present to the user.

4.2. Results Analysis

4.2.1. Analysis of the Effectiveness of Maintenance Decisions and Guidance

- Emergency cooling and cause investigation for transformer overheating.

- Emergency handling of circuit breaker failure after line protection activation.

- Abnormal handling of online monitoring data for unusual noise and partial discharge inside high-voltage switchgear.

- Inspection and preliminary localization of cable fault points within underground cable trenches (or tunnels).

- Fault location and isolation of feeder ground faults in station DC systems.

- System status verification and resetting after protection device maloperation.

- Troubleshooting for emergency lighting system startup failure.

- Abnormal parameter alarm handling and setpoint verification during the initial operation phase of new equipment.

4.2.2. Information Push Delay Analysis

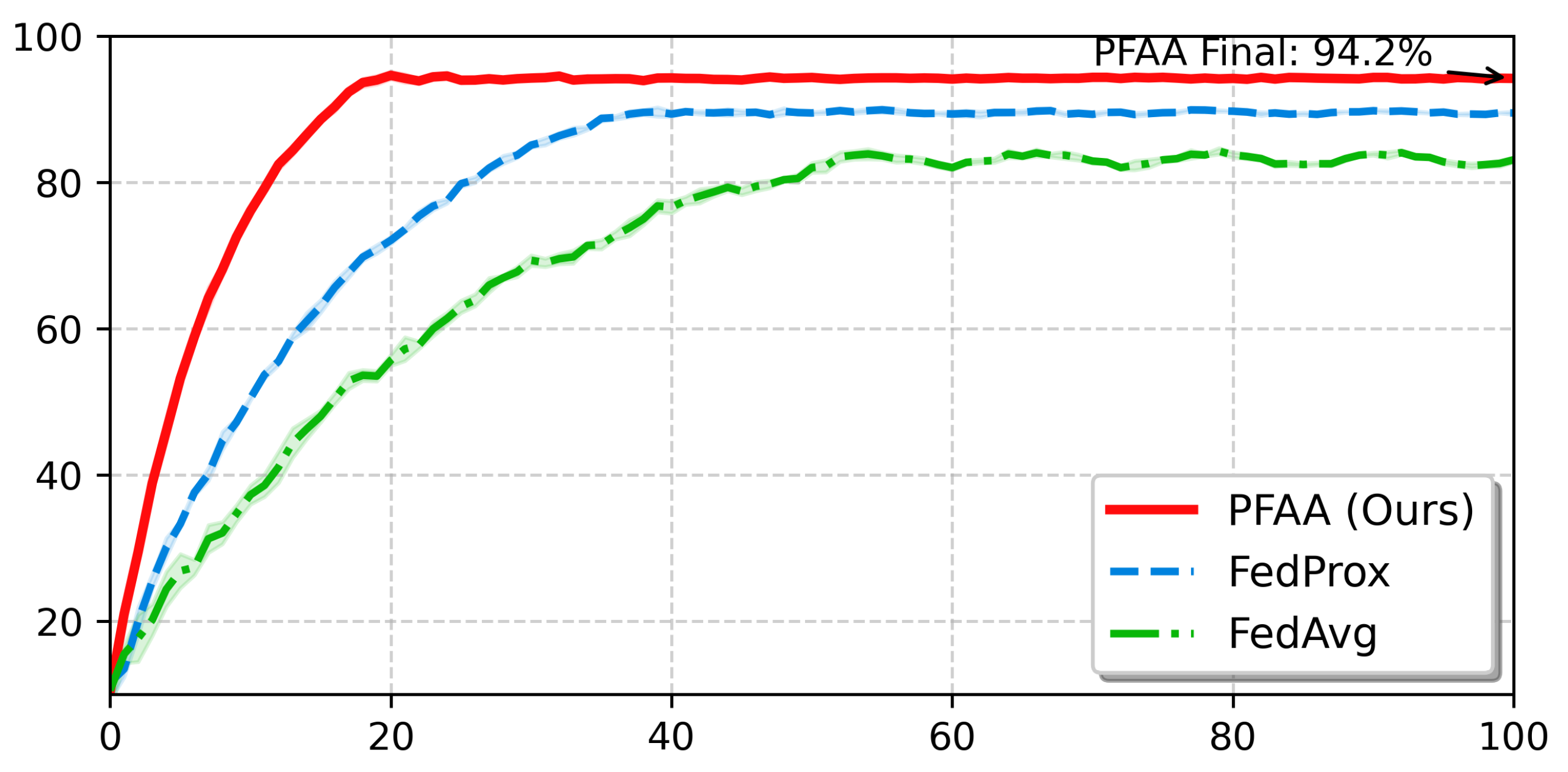

4.3. Algorithmic Performance Evaluation

4.3.1. Comparison with Baselines

4.3.2. Ablation Study

- Baseline (FedAvg): Standard aggregation based on sample size ().

- Static-Weighted: Aggregation using fixed weights derived from initial device types without dynamic attention.

- PFAA (Ours): Dynamic, fingerprint-aware attention aggregation.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sujanthi, S. Augmented reality for industrial maintenance using deep learning techniques—A review. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT), Bengaluru, India, 4–6 January 2024; pp. 1629–1635. [Google Scholar]

- Kadry, S. On the evolution of information systems. Syst. Theory Perspect. Appl. Dev. 2014, 1, 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Porawagamage, G.; Dharmapala, K.; Chaves, J.S.; Villegas, D.; Rajapakse, A. A review of machine learning applications in power system protection and emergency control: Opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Front. Smart Grids 2024, 3, 1371153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, M.D.; Soshi, F.T.J.; Biswas, P.; Ferdous, A.S.; Rashid, A.; Biswas, A.; Gupta, K.D. Principles and Components of Federated Learning Architectures. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.05273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benes, K.J.; Porterfield, J.E.; Yang, C. AI for Energy: Opportunities for a Modern Grid and Clean Energy Economy; US Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- McMahan, H.B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B.A.y. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.05629. [Google Scholar]

- Breitkreuz, D.; Müller, M.; Stegelmeyer, D.; Mishra, R. Augmented reality remote maintenance in industry: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Extended Reality, Lecce, Italy, 6–8 July 2022; pp. 287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Ong, S.K.; Nee, A.Y. A context-aware augmented reality system to assist the maintenance operators. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2014, 8, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reljić, V.; Milenković, I.; Dudić, S.; Šulc, J.; Bajči, B. Augmented reality applications in industry 4.0 environment. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Q.; Dai, W.; Chen, M.; Liu, X.; Pirttikangas, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Herrera-Viedma, E. A survey on federated learning and its applications for accelerating industrial internet of things. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.10501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lu, Q.; Yu, Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lo, S.K.; Chen, S.; Xu, X.; Zhu, L. Blockchain-based federated learning for device failure detection in industrial IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 5926–5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkani, M.R.A.; Chouchane, A.; Himeur, Y.; Ouamane, A.; Miniaoui, S.; Atalla, S.; Mansoor, W.; Al-Ahmad, H. Advances in federated learning: Applications and challenges in smart building environments and beyond. Computers 2025, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.M.S.; Zafar, M.H.; Abou, Houran, M.; Qadir, Z.; Moosavi, S.K.R.; Sanfilippo, F. Enhancing cybersecurity in Edge IIoT networks: An asynchronous federated learning approach with a deep hybrid detection model. Internet Things 2024, 27, 101252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, H.; Lu, Q.; Yan, J.; Ji, S.; Ma, Y. Research on medical image classification based on improved fedavg algorithm. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2025, 30, 2243–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonhe, L. A literature review of information dissemination techniques in the 21st century era. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2017, 1731. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, P.; Lu, G.; Jiang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Hu, J.; Yan, J. Cyber intrusion detection through association rule mining on multi-source logs. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 4043–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H.; Janicke, H.; Ferrag, M.A.; Abuadbba, A. Multi-aspect rule-based AI: Methods, taxonomy, challenges and directions towards automation, intelligence and transparent cybersecurity modeling for critical infrastructures. Internet Things 2024, 25, 101110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razgon, M.; Mousavi, A. Relaxed rule-based learning for automated predictive maintenance: Proof of concept. Algorithms 2020, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenhao, Z. Push Content Decision Method for On-Site Operation and Maintenance of Power Communication Network; Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Gao, G.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liao, Y. An AR based edge maintenance architecture and maintenance knowledge push algorithm for communication networks. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Big Data and Computing, Guangzhou, China, 10–12 May 2019; pp. 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Zaheer, M.; Sanjabi, M.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proc. Mach. Learn. Syst. 2020, 2, 429–450. [Google Scholar]

- Arivazhagan, M.G.; Aggarwal, V.; Singh, A.K.; Choudhary, S. Federated learning with personalization layers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.00818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Field Name | Instance Data | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Timestamp | “2025-05-02 10:00:00” | Data record timestamp |

| Device_id | “TX-001” | Unique Device Identifier |

| Voltage_phase_a | 220.5 V | Phase A voltage |

| Current_phase_a | 15.2 A | Phase A current |

| Temperature_winding | 75.6 °C | Winding temperature |

| Oil_level | 95.2% | Oil level |

| Vibration_x | 0.5 mm/s | X-axis vibration |

| Gas_in_oil_h2 | 10 ppm | Hydrogen (H2) content in dissolved gas in oil |

| Fault_type | Normal, winding short circuit, etc. | Fault Type (e.g., normal, winding short circuit, low oil level, overheating) |

| Maintenance | “2024-09-15: Routine check,…” | Maintenance Log (including detailed operations) |

| Method | Component | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (FedAvg) | Sample Size Only | 83.1 | 81.2 | 79.5 |

| Static-Weighted | +Metadata (Fixed) | 88.4 | 86.7 | 85.3 |

| PFAA (Ours) | +Dynamic Attention | 94.2 | 93.8 | 94.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, C.; Li, X.; Lei, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Shao, S. Client-Attentive Personalized Federated Learning for AR-Assisted Information Push in Power Emergency Maintenance. Information 2025, 16, 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121097

Ye C, Li X, Lei Z, Wang J, Zhang T, Shao S. Client-Attentive Personalized Federated Learning for AR-Assisted Information Push in Power Emergency Maintenance. Information. 2025; 16(12):1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121097

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Cong, Xiao Li, Zile Lei, Jianlei Wang, Tao Zhang, and Sujie Shao. 2025. "Client-Attentive Personalized Federated Learning for AR-Assisted Information Push in Power Emergency Maintenance" Information 16, no. 12: 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121097

APA StyleYe, C., Li, X., Lei, Z., Wang, J., Zhang, T., & Shao, S. (2025). Client-Attentive Personalized Federated Learning for AR-Assisted Information Push in Power Emergency Maintenance. Information, 16(12), 1097. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121097