3. Virtualization Architecture of Human Movement in the Virtual World of the Metaverse, Spatial Distortion in the Virtual World of the Metaverse and the Factors That Lead to It

The rapid development of platform technologies provides a solid basis for the emergence and development of complete metaverses—vast 3D digital spaces where users can interact with each other, with virtual objects, and the surrounding environment through their digital avatars. Going beyond the limits of the 2D concept, the metaverse promises to bring a living world where work, entertainment, and social interaction are approached comprehensively. The core element that needs to be promoted in the metaverse is the creation of an “immersive” experience for users. Users do not just “look” at the virtual world; they need to feel that they are actually “present” in it. This presence relies heavily on the ability to accurately and instantly reflect every action and gesture of the user in the real world into the virtual environment through the avatar. From a wave, a nod, to complex steps, everything needs to be reproduced smoothly and naturally.

Therefore, coming up with standards and norms for building an architecture that can effectively simulate user movements has become one of the top technological challenges. Such architecture is responsible not only for collecting user movement data, processing it, and transmitting it over the network with the lowest latency, but also for ensuring that the avatar in the virtual world can accurately reproduce those movements.

Many organizations and communities in the field of telecommunications development around the world are developing standards to make “Metaverse” concepts a reality. Typical examples include: the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Metaverse Focus Group 4 with standards FGMV-28 [

14], FGMV-29 [

15]; the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) with standards IEEE 2888.3 [

16], IEEE 2888.4 [

17]; and others. In their research, Kyoungro Yoon, Sang-Kyun Kim, and their colleagues summarize the main content of the IEEE 2888 standard, which is designed to connect the physical world with virtual environments. They also visualized this standard with Draft Architecture for Virtual Reality Disaster Response Training System with Six Degrees of Freedom (6 DoF) [

18].

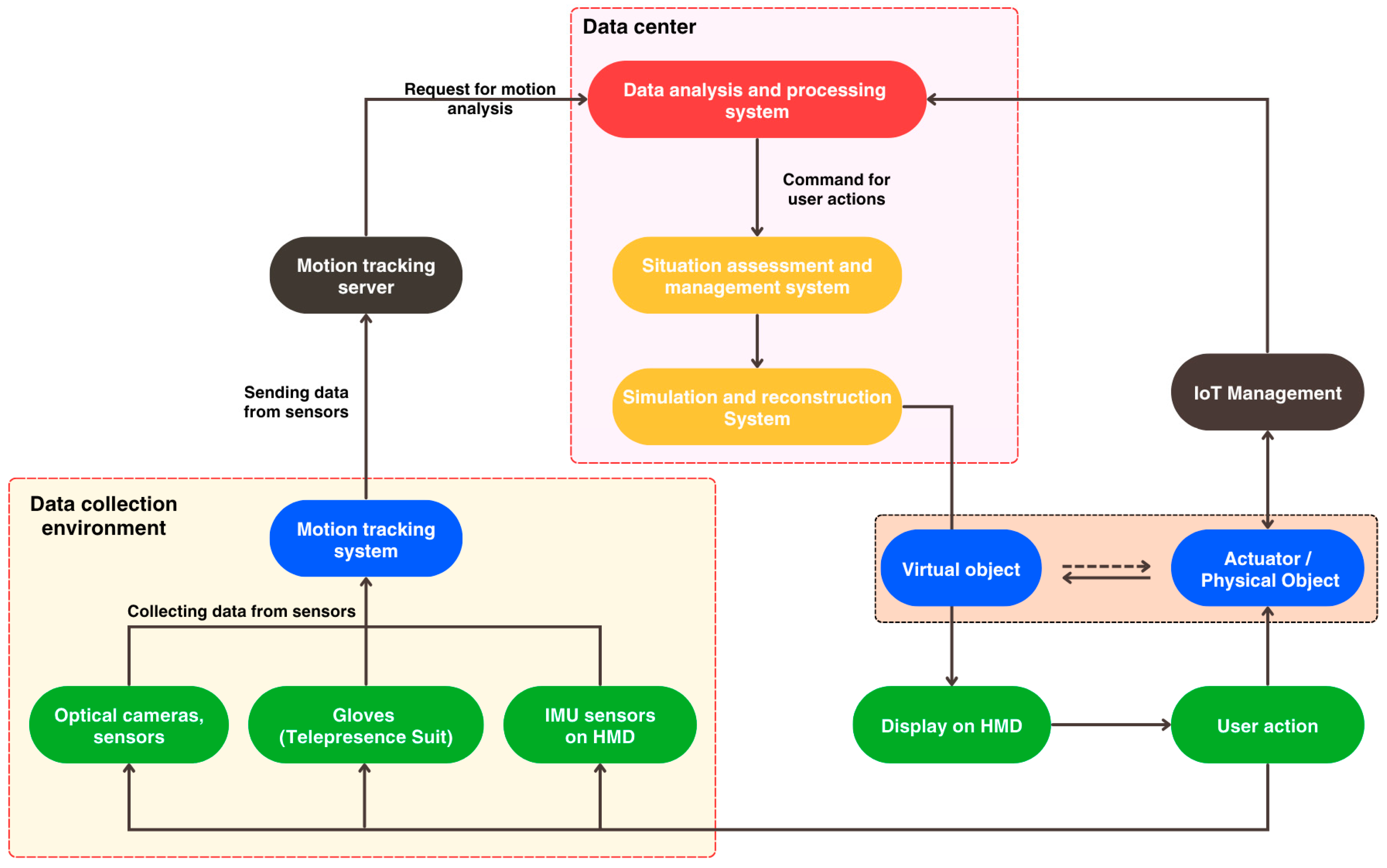

Figure 1 shows the architecture of user behavior virtualization in the metaverse virtual environment according to the IEEE 2888.4 standard.

Sensors, cameras, touch gloves, or telepresence suits collect data about the user and the environment. Aggregated data from the motion tracking system is sent to the motion tracking server. The motion tracking server processes the data and sends analysis requests to the computing system (Data Center). Here, the analysis and processing system receives the input data, analyzes the movement, and sends commands for user actions. The situation assessment system analyzes the received data, issues commands in response to the user’s actions within the virtual environment, and sends them to the simulation and reconstruction system. The situation assessment system analyzes the received data, issues commands in response to the user’s actions from the virtual environment, and sends them to the modeling and reconstruction system. Here, the system predicts and simulates the user’s movements and the environment based on the collected data. Simulation models, integrated together and displayed in a “virtual” form in the HMD, simulate the feedback of the virtual object/environment with the user’s actions. Internet of Things (IoT) devices convey to users the sensation of feedback from virtual objects/environments, while simultaneously collecting and transmitting data to the system for modeling assessment and calculation of the user’s next actions.

The metaverse is not only a technological trend but also opens opportunities for breakthroughs in many fields. Typical applications include virtual classrooms or experimental modeling in education; psychotherapy, telemedicine in the medical field; virtual office, virtual store in commerce and business; and others.

Currently, one of our key research projects is being conducted in Mega Lab 6G of the Saint Petersburg State University of Telecommunications named after Prof. M.A. Bonch-Bruevich is aimed at applying the metaverse in the field of medicine. We were fortunate to meet and exchange experiences with leading doctors. They shared with us a method of treatment based on psychotherapy for patients who, after severe injuries, are almost unable to move or move. When a patient unfortunately suffers a serious injury to a limb or other body part, muscle rehabilitation is very important to avoid muscle atrophy and loss of mobility. Treatment is usually performed using massage in combination with physiotherapy. Recent medical research has shown that muscle stimulation through sensory memory in areas of the brain responsible for motor control or associated with sensation and pain has a more positive effect in the rehabilitation treatment of patients after severe injury [

19].

With our efforts, we have obtained the first results of this research. However, there are difficulties that we encounter. The most typical is the virtualization of real-world objects into a virtual environment. The size and coordinates of the object, as well as the simulation of the user’s actions affecting the environment, have relatively large errors compared to the real version. This phenomenon in the field of augmented and virtual reality is also being researched and discussed, and can be called unintended “unintended spatial distortion” in the virtual world [

10]. This is a key factor in determining the feasibility of this research. The metaverse, especially in the medical field, should provide users with the most realistic sensation, both visual, auditory, and tactile, like what they experience in the real world. Therefore, this issue needs to be studied and considered deeply and comprehensively.

There are many causes that can lead to this phenomenon, which are divided into two main groups: human factors and technical factors.

In the course of our research, we present technical factors that may lead to spatial distortion in virtual worlds within the Metaverse, which are systematized in

Figure 2.

The energy factor does not directly lead to spatial distortion in the virtual world, but is an important fundamental factor that ensures a reliable infrastructure for the entire system, from data processing performance, images, to simulation models, etc. Lack of Energy for processing can lead to errors and omissions in data collection, processing, and operations in the virtual world, which in turn leads to errors in the virtualization process.

Like energy, the Internet is an important component of the Metaverse infrastructure and a foundation for carrying out other functions. There are four aspects of Quality of Service (QoS) on the Internet that need to be considered: latency, bandwidth, jitter, and packet loss [

20].

Like the Internet quality of service (QoS) requirements for virtual or augmented reality application domains, the metaverse requires an Internet with extremely low latency and high bandwidth. High latency will lead to a situation where data cannot be updated in a timely manner, especially when simulating the movement of objects in the real world. This can lead to positioning errors in the virtual space, which may even cause motion sickness in users. Low bandwidth prevents data from being processed and transmitted on time, causing it to be rendered in the virtual environment as incomplete or simplified models, losing the necessary detail. Latency fluctuations cause instability in the transmission and rendering of graphics and other data of virtualized objects. Packet loss is an extremely important factor when considering the realism and high precision of virtualization in virtual environments. When data files are not transmitted or are lost during transmission, the object is not simulated, or parts of the object are not fully simulated in the virtual space.

In general, the quality of Internet service directly affects the stability, authenticity, and integrity of space and real-world objects that are modeled and reconstructed digitally in the virtual environment. The four elements of QoS on the Internet interact with each other and affect the quality of the virtual world. Therefore, they must be considered simultaneously and comprehensively.

There are three main groups of devices considered here: a group of data collection devices, a group of image display devices, and a group of devices that help users interact with the virtual environment.

Data acquisition devices include sensor systems, cameras, and more. As the name suggests, their role is to collect data according to the function of each type of device provided to the system, to analyze and process the information for simulation in a virtual environment.

Visual display devices include head-mounted displays (HMDs), virtual reality glasses, or projection systems. They help users and those around them observe what is happening in the virtual world. Visual display devices include head-mounted displays (HMDs), virtual reality glasses, or projection systems. They help users and those around them observe what is happening in the virtual world.

Devices that help interact with virtual environments include touch gloves, portable controllers, telepresence suits, and others. They allow users to interact and perform actions in a virtual environment. Based on the data transmitted from these devices, the system models the user’s behavior in the virtual environment.

Currently, the quality of these optimized devices is extremely high. However, technical inaccuracies still exist, even if they are very minor. When using a metaverse system, many data collection devices are required. Therefore, if the permissible error of all these devices is not properly controlled, the collected error will have a clear difference compared to reality. This will lead to errors in the entire system, and the consequence will be spatial distortions in the virtual world.

This is an extremely important fundamental component of the entire system. Two main aspects are considered: hardware and software (algorithms).

Hardware includes the central processing unit (CPU), graphics processing unit (GPU), random access memory (RAM), and others. When the amount of data being processed exceeds the hardware limit, the data is not fully updated in real time, which leads to distortion effects such as spatial scaling or frame stuttering.

The computing system processes data incorrectly or uses inefficient algorithms, such as simulating a collision between two spherical solid objects on a straight line in the real world, causing them to pass through each other or move in an unnatural manner instead of moving in the opposite direction of their original motion.

Solving the problem of virtualization in the metaverse requires the use of many different algorithms. These include data analysis and synthesis algorithms, data synchronization algorithms, simulation (digital reconstruction) algorithms, integration algorithms, and other algorithms.

Data analysis and synthesis algorithms help analyze and synthesize data transmitted from sensors, cameras, user devices, etc., in order to filter out noise, detect errors, and format the data in a way that is suitable for a computing system.

Data is collected from multiple device sources and distributed sensors. Each device has its own characteristics. Data synchronization algorithms help maintain consistency, reduce errors, prevent information conflicts, minimize latency, and optimize data transmission between system components.

Simulation (digital reconstruction) algorithms include user avatar simulation, environment simulation, object/person simulation, physics simulation algorithms, behavior simulation algorithms, and other algorithms. These algorithms are required to ensure high accuracy to create a realistic user experience and a sense of presence in the real world. However, this remains a challenge in metaverse environments.

Integrating simulation models and digital reconstruction into one virtual environment is also a serious challenge. The data from many different models is very large and complex; the models overlap, so the integration algorithms must provide very high accuracy.

These algorithms play an important role in solving each stage of the virtualization process from reality to the virtual world, as well as in managing the virtual environment. Incorrect processing of these algorithms will directly lead to spatial distortions in the virtual environment.

In summary, the development of modern technologies provides a foundational platform for the emergence and evolution of metaverses in the near future, where users not only “look” into the virtual world but must truly “feel” present within it. This presence relies heavily on the ability to accurately and instantly reflect every action and gesture of the user in the real world into the virtual environment through the avatar. To achieve that, one of the important issues that needs to be carefully considered is the unintended spatial distortion in the virtual world. There are many causes that can lead to this phenomenon, which are divided into two main groups: human factors and technical factors. In our research, we have identified technical and hardware-related factors that contribute to this phenomenon, including energy issues, internet QoS, device limitations, as well as processing and computing systems. Various approaches are being researched and implemented to overcome the above challenges. In particular, optimized algorithms are improved to enhance system performance, while AI is utilized to support device management, data processing, and more efficient computational operations. This is also the next research and development trend of the metaverse, as well as other related technologies.

4. Improving the Accuracy of Avatar Motion Based on the Gaussian Process Regression Method

4.2. Real-Time Data Filtering Using Gaussian Process Regression

For continuous data, such as results from sensor measurements, in recent years, the Gaussian process regression method has emerged as a solution for models where the relationships between the data are complex and nonlinear. Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) is a non-parametric machine learning method based on probability theory that uses Gaussian processes to model data. Unlike many traditional regression methods that aim to estimate the parameters of a predefined function, GPR works by defining a probability distribution directly over the space of functions that can describe the observed data [

25]. This approach has two main advantages: first, GPR can model complex and nonlinear relationships in data without requiring strict assumptions about the functional form; second, it provides not only predicted values but also a quantitative assessment of the uncertainty associated with each prediction. It is this capability that makes GPR such a powerful and flexible tool [

26]. A Gaussian process is defined as a collection of random variables, any finite subset of which follows a Gaussian distribution. However, the biggest problem this method faces is the complexity of the algorithm and the memory requirements for large datasets. Therefore, it is not suitable for real-time processing tasks.

To overcome the limitations mentioned above, variations in this method are being developed and enhanced accordingly. In this research, the Sparse Variational Gaussian Process (SVGP) is used. SVGP uses a small set of inducing points to provide an approximate representation of the posterior distribution instead of working directly with the entire dataset. This allows for a significant reduction in computation time, resource consumption, and memory usage, while simultaneously speeding up the processing. The implementation of SVGP is shown in

Figure 3.

The basic working principle of SVGP is to use variational methods to approximate a complex real posterior distribution

p(

f|

y) by computing a more easily manipulated variational distribution

q(

f), which serves as an approximate distribution. Instead of calculating the exact posterior distribution, which is often difficult to determine, we seek the “best” approximation in a family of simpler distributions, which is defined as follows [

27]:

where

u—inducing points selected from the full range of values;

q(u)—variational distribution over the variables u;

—conditional distribution of the latent function f at any point, given the function values at the inducing points u are known.

The variational distribution

q(

u) is often chosen to be a simple and easy-to-use distribution, the most common of which is the multivariate Gaussian distribution:

where

m—expected vector (mean);

S—covariance matrix.

Step 1: Train and save the SVGP model weights

This step is performed on a server or on computing systems with sufficiently powerful hardware.

For the model to “learn” the characteristics of the prior values, the following components of the SVGP model need to be defined [

28]:

- −

Mean function μ(u) defines the prior mathematical expectation of the Gaussian process. It serves as the “baseline” for the model’s predictions. A simple and common choice for this function is a constant μ(u) = C, where C is a constant optimized during the training process.

- −

The covariance function, or kernel function, defines the prior covariance structure of the Gaussian process, describes the degree of similarity between data points, and influences the shape of the modeled function. Various algorithms act as covariance functions. In this research, Scalekernel is used as a covariance function, which is defined as follows:

where

—output scale parameter;

—Matern kernel matrix;

—smoothness parameter;

Г(.)—gamma function;

d—distance between two arbitrary induced points ui and uj;

Θ—lengthscale parameter, which controls the range of influence between points;

—modified Bessel function of the second kind.

—The modified Bessel function of the second kind is one of two linearly independent solutions of the modified Bessel differential equation:

- −

The Likelihood Function defines the relationship between the values of the latent function

f and the observed labels

y. It describes how noise is added to the values of the latent function to obtain the observed data. Gaussian Likelihood is the standard likelihood function and is defined as follows:

where

—random noise sampled from a normal distribution;

—noise variance parameter.

The main goal of training the SVGP model is to optimize the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO)—the variational lower bound or loss function. It is important to note that optimizing the ELBO is mathematically equivalent to minimizing the Kullback–Leibler divergence between the approximate (predicted) posterior distribution and the actual posterior distribution. Many versions of ELBO have been successfully studied, including VariationalELBO [

29] (Hensman et al., 2014), PredictiveLogLikelihood [

30] (Jankowiak et al., 2020), GammaRobustVariationalELBO [

31] (Knoblauch, 2019). They have advantages and disadvantages compared to each other. In this research, considering the nature of the data and possible technical limitations of the equipment, the VariationalELBO was used as the loss function, which is defined as follows:

where

N—the number of data points.

There are 2 main components in formula (8):

- −

The first component is the expected log-likelihood under the variational distribution

q(

f), which measures how well the model fits the observed data:

- −

The second component is the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between the variational distribution q(u) and the prior distribution p(u):

where

β—proportionality constant that reduces the adjustment effect of the KL divergence,

β = 1 leads to the true variational ELBO.

This component acts as a regularization mechanism, encouraging q(u) not to deviate too far from the prior distribution. This helps prevent overfitting and maintain the plausibility of the probabilistic model.

In the field of machine learning in general, algorithms developed for model optimization aim to minimize the ‘loss function’ by adjusting the model’s weight. The general mechanism of these algorithms operates by moving in the opposite direction of the increasing gradient (the derivative of the loss function). The gradient points in the direction of greatest increase, and going in the opposite direction means “going down the hill” to the point of minimum error.

Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) is one of the most popular, widely used, and effective adaptive learning rate optimization algorithms in machine learning models [

32,

33]. This optimization method is also used in this research. It combines ideas from Momentum and RMSProp to achieve fast and stable convergence. Momentum aims to accelerate the gradient in a consistent direction by adding a portion of the previous gradient to the current gradient. In other words, the gradient accumulates “momentum” over time, allowing the model to ignore ‘flat’ regions and reduce oscillations in areas with rapidly changing “slopes”. Meanwhile, RMSProp adjusts the learning rate for each individual parameter based on its variance. Parameters with large gradients receive smaller update steps, while parameters with small gradients receive larger ones.

The process of updating the parameters of the Adam optimizer model θ at time t includes the following steps:

- −

- −

Gradient moving average update:

- −

Update the moving average squared gradient:

- −

- −

where

—gradient operator with respect to

;

β1—decay rate for the first moment estimate;

β2—decay rate for the second moment estimate;

α—learning rate (step size);

ϵ—small constant to prevent division by zero when

it is very small.

This process is performed continuously for all values of the model’s training data and repeated many times to find the optimal parameters. At each training cycle (epoch), the data is split into random mini-batches that are fed to the model. ELBO is computed for each mini-back. Gradients are computed using the backward pass. Then, the model parameters are updated using the Adam optimizer.

Once the model has been trained, the best-performing weight sets are saved and passed to the SVGP, where they are used to process the data obtained from the potentiometers.

Step 2: Prediction (Use) with SVGP

In this step, the model can be deployed on edge data collection devices (without strict hardware requirements). Here, the SVGP model loads the set of weights transmitted from the server after training for further use.

To predict a new value

x*, SVGP computes the predictive distribution

[

34]:

In which:

where

—the covariance vector between the test point x* and the inducing points;

—the covariance matrix of the inducing points;

m—the mean vector of the variational distribution q(u);

—the prior variance at the test point x*;

—the transposed matrix of

—the covariance matrix of the variational distribution

.

4.3. Simulate and Evaluate the Results Obtained by the SVGP Method with Traditional Methods

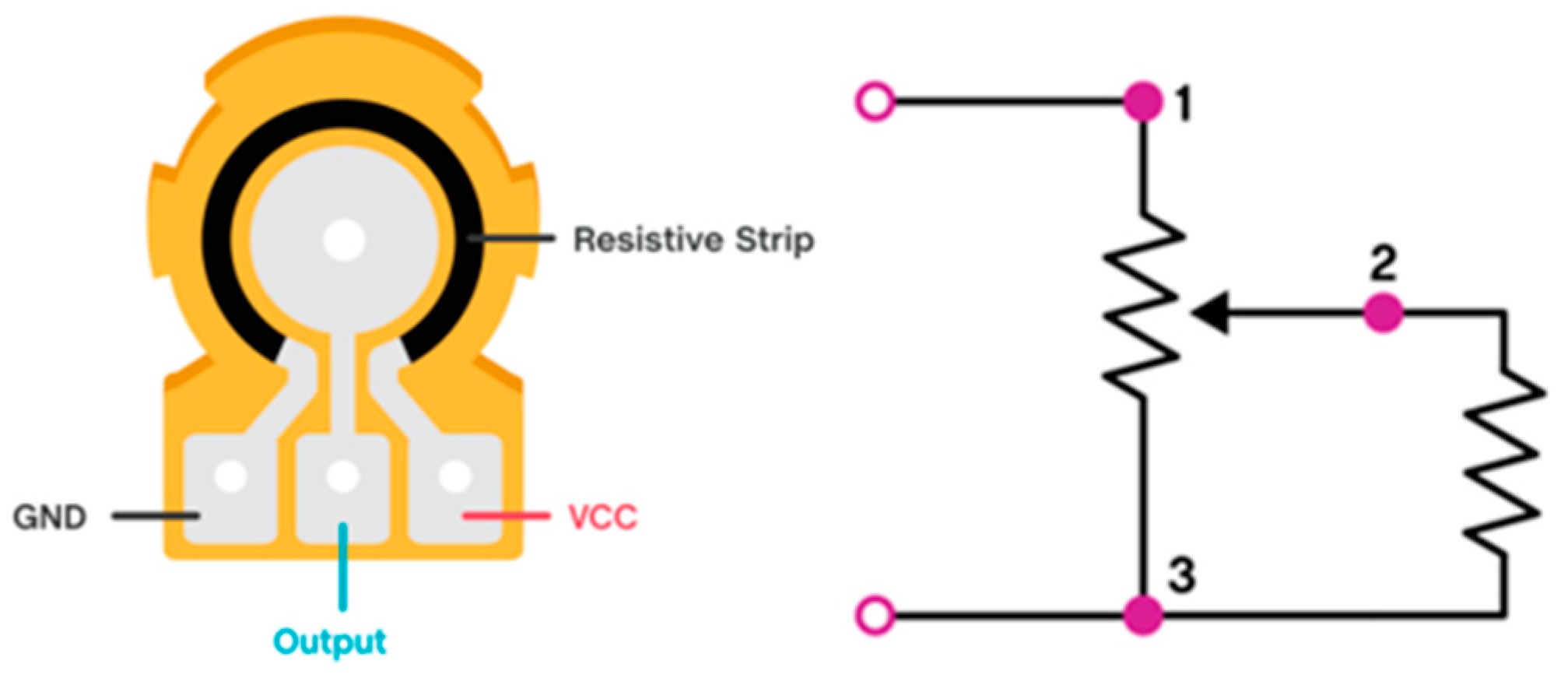

In this research, we use synthetic data. The dataset is simulated based on the real technical specifications of the Potentiometer 503 (

Figure 4), taking into account the positional relationships between the potentiometers during the process of capturing the user’s motion parameters. From this ideal dataset, we further consider and compute various types of noise and device errors that occur during measurement, thereby obtaining a noise-contaminated dataset. The types of noise and errors considered include:

- −

Thermal noise: random noise caused by the thermal motion of electrons in the resistor.

- −

Contact noise [

35]: caused by imperfect contact between the wiper and the resistive layer;

- −

Electromagnetic interference (EMI) [

36]: environmental effects causing;

- −

Temperature drift: resistance changes due to ambient temperature variation.

- −

Hysteresis: caused by mechanical friction and material elasticity;

- −

Missing data: simulating communication failures or ADC read errors;

- −

Analog-to-digital converter noise [

37];

- −

Burst errors and outliers: caused by strong impulse noise or temporary disconnections.

To collect the user’s motion data, four potentiometers are set up in the following positions:

- •

A potentiometer mounted on the lateral side of the shoulder, with its axis of rotation parallel to the body, partially attached to the torso and partially to the arm, measuring the shoulder elevation angle, set as the origin of the coordinate system;

- •

A potentiometer mounted on the upper part of the shoulder, with its axis of rotation parallel to the longitudinal axis of the humerus, measures the arm rotation angle.

- •

A potentiometer mounted on the elbow, the axis of rotation parallel to the axis of flexion of the elbow, at a distance of about 30 cm from the shoulder potentiometers.

- •

A potentiometer mounted on the wrist, the axis of rotation parallel to the axis of flexion/extension, at a distance of about 25 cm from the elbow potentiometer.

In this reseach, we used the 503 potentiometer model (WH148) manufactured by Chengdu Guosheng Technology Co., Ltd., Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, China. The main parameters of the 503 potentiometers are as follows:

- •

Input voltage: Vcc = 5 V;

- •

Total resistance: Rtotal = 50 kΩ.

These potentiometers are configured to have the same time markers for data recording.

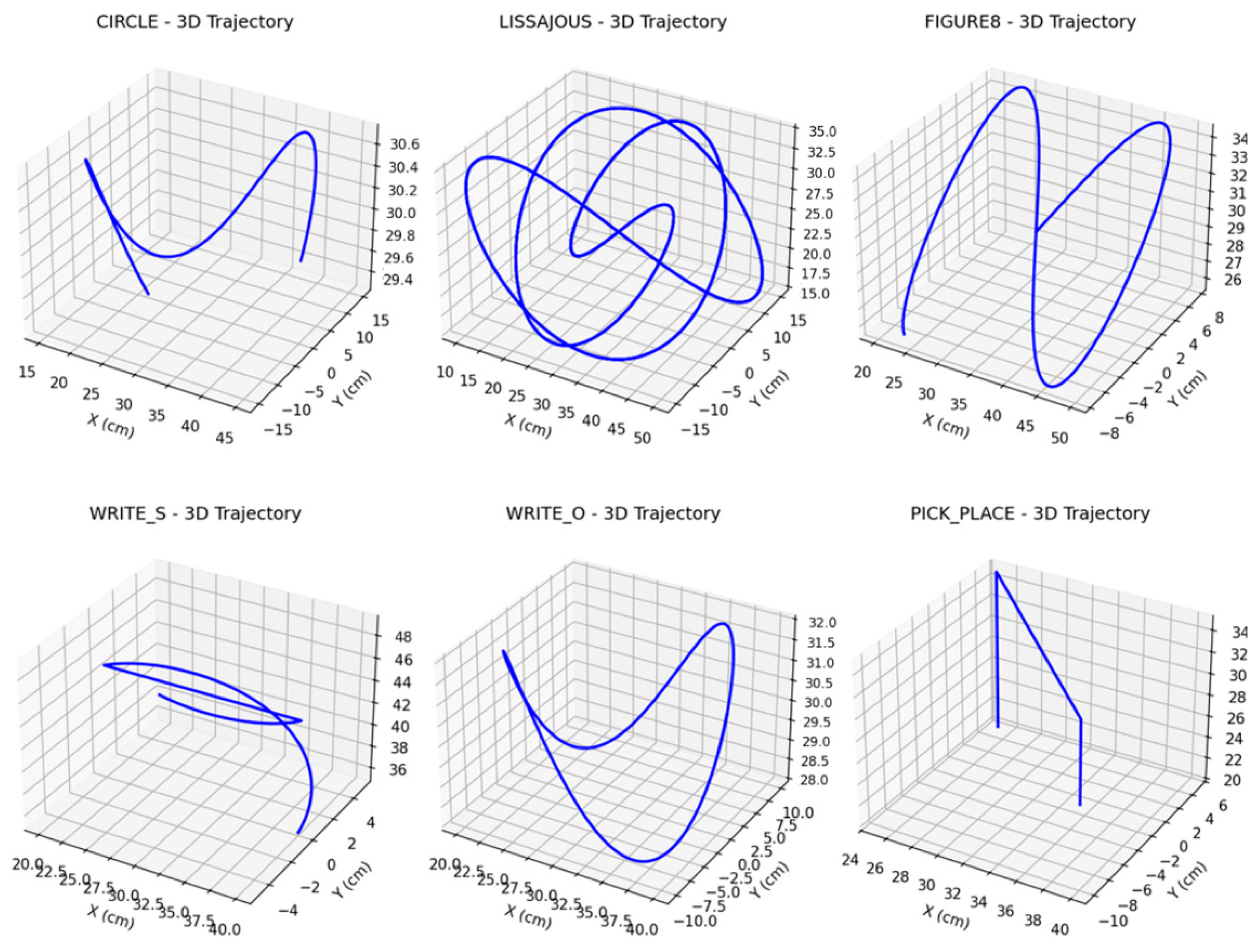

We simulate 60 different types of user movements, with approximately 1000 samples for each type. These movements are based on six main categories, including circle, Lissajous, figure eight, write S, write O, and pick and place (

Figure 5). From each type of movement, one dataset is selected for training the model.

The simulated data of the user’s arm motion is collected by a potentiometer placed at the shoulder to measure the shoulder pitch angle, for the motion trajectory types shown in

Figure 6. It can be seen that the collected data has complex nonlinearity, so traditional methods such as the standard Kalman filter are not effective due to the requirement of data linearity.

To train the SVGP model, we used hardware from an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050 laptop GPU and utilized the built-in Gpytorch library [

28] to inherit and modify the model with the following parameters:

- •

Window sliding: 10 (helps the model learn the relationships between consecutive samples)

- •

Kernel hyperparameters: MaternKernel with smoothness parameter (ν = 2.5) and Automatic Relevance Determination equal to the size of the window sliding

- •

Number of inducing points: 300 randomly selected; however, their positions are learned and automatically optimized during training to minimize the loss at each epoch

- •

Mini-batch size: 128

- •

Number of epochs: 150

- •

Optimizer parameters: Adam with a learning rate of 0.01

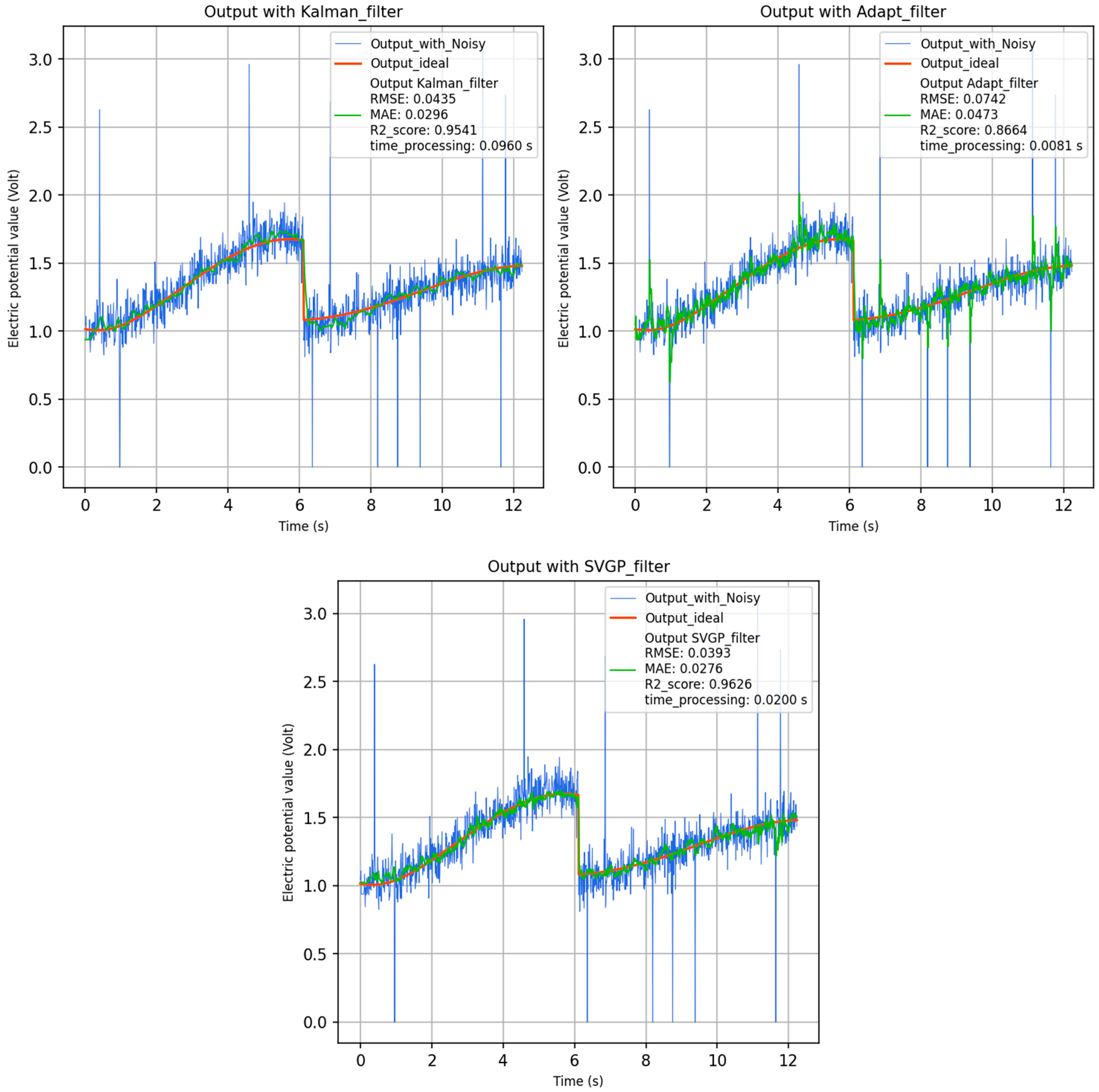

Evaluation of the deployability of SVGP on edge devices, where the hardware is not powerful enough. The pre-trained SVGP was executed on the device’s CPU, and its filtering results were compared with two other filtering methods on the same type of device for nonlinear data, including: Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) and an adaptive moving average filter, using data from the potentiometer placed at the shoulder to measure the shoulder pitch angle. The results for the motion trajectory “write-S” are shown in

Figure 7.

Table 1 presents the signal processing performance for different motion trajectories.

In addition to considering processing speed, the performance of the filters is evaluated based on the following three metrics, which are defined as follows:

- −

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE):

- −

Mean Absolute Error (MAE):

- −

where

—data recorded by the potentiometer under ideal conditions;

—data after processing by the filter;

—average value of data recorded by the potentiometer under ideal conditions.

It should be noted that the time values reported in the table represent the total processing time for all samples (excluding data transmission between devices and the handling of outliers). Therefore, the actual processing time per sample can be calculated by dividing the table values by approximately 1000, which is the number of samples per trajectory type.

From the collected data, it can be observed that the fastest data processing is achieved by the adaptive filter. For relatively simple or moderately complex motions such as Circle or Write S, the UKF demonstrates the highest performance, although the difference compared to SVGP is negligible; however, its processing time is 4–5 times longer. For more complex motions, such as Lissajous, Figure 8, Write S, and Pick and Place, SVGP demonstrates significantly better processing performance compared to the other two methods, while its processing speed shows only a slight difference relative to the adaptive filter. This indicates that, in simulated motion scenarios, SVGP provides a balanced trade-off between performance and data processing speed.

Compared to methods such as Cubature Kalman filters (CKF) or Particle Filter (PF). CKF is considered to perform better than UKF in many cases [

38,

39]. Similarly to UKF, it provides effective signal processing for motions ranging from simple to moderately complex, with faster speed. However, a common limitation of Kalman filtering methods is that for highly nonlinear and complex motions, their processing capability is restricted. This limitation is better addressed by PF, but the main drawback of PF is its algorithmic complexity, which results in significantly slower processing speed compared to Kalman-filtering methods [

40].

Furthermore, when evaluating the feasibility of SVGP compared to other processing methods, in addition to performance and processing speed, another critical factor to consider is the cost of deployment and operation. For the goal of building a system capable of processing data directly on edge devices to reduce the load on central systems, such as in the Metaverse, the algorithm must strike a balance among all three factors. Other modern AI-based methods, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) multi-frame fusion filtering, require training datasets with tens of thousands of samples and a large number of hyperparameters. In contrast, SVGP only requires around 1000 to a few thousand samples for training and a small number of hyperparameters to learn the data characteristics. This results in significant differences in training time, model size, memory requirements, and computation speed, making SVGP more suitable for deployment on edge devices.

In summary, the SVGP-based filtering method provides a balanced signal processing solution, optimizing processing speed, performance, and operational and deployment costs. It has the potential to become a promising approach for data processing on edge devices with limited hardware resources in real-time systems, such as the Metaverse. The main challenges of this method lie in the following two aspects:

- −

Determining the number of inducing points: if the number of inducing points is too small, the model may underfit; if the number is too large, it increases memory usage and computation time, which slows down data processing speed.

- −

Ensuring training data: In practice, it is very difficult to provide the model with highly accurate data for training. Deploying high-precision measurement devices is complex and costly. In addition, a diverse range of data covering different motion trajectories is required. However, once the model is successfully trained, it can significantly reduce deployment costs and be applied on a large scale. This is particularly useful for wide-area distributed systems such as the Metaverse.

Using the data filtered by the SVGP method for the rendering process of the data collected by the four aforementioned potentiometers and comparing it with unfiltered data or data processed by an inefficient method, the results are shown in

Figure 8.

From the results obtained, it is easy to see that the data filtered by the SVGP method brings high accuracy, and insignificant deviation compared to data collected under ideal conditions. Conversely, data that is not filtered for noise or filtered using methods that require linearity introduces significant errors.

In summary, human motion data collected from sensors in real-time systems such as the metaverse are often nonlinear in nature. Meanwhile, traditional filters, e.g., Kalman, are designed for linear or near-linear systems with slowly varying parameters. This makes traditional filters ineffective, leading to significant errors in motion reconstruction. Applying AI to data processing provides effective methods to deal with this problem. For continuous data such as sensor measurements, SVGP is a powerful, efficient, and suitable solution for the noise filtering problem in nonlinear motion tracking systems.