Liveness over Fairness (Part I): A Statistically Grounded Framework for Detecting and Mitigating PoW Wave Attacks

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Novel Contributions Beyond Existing Work

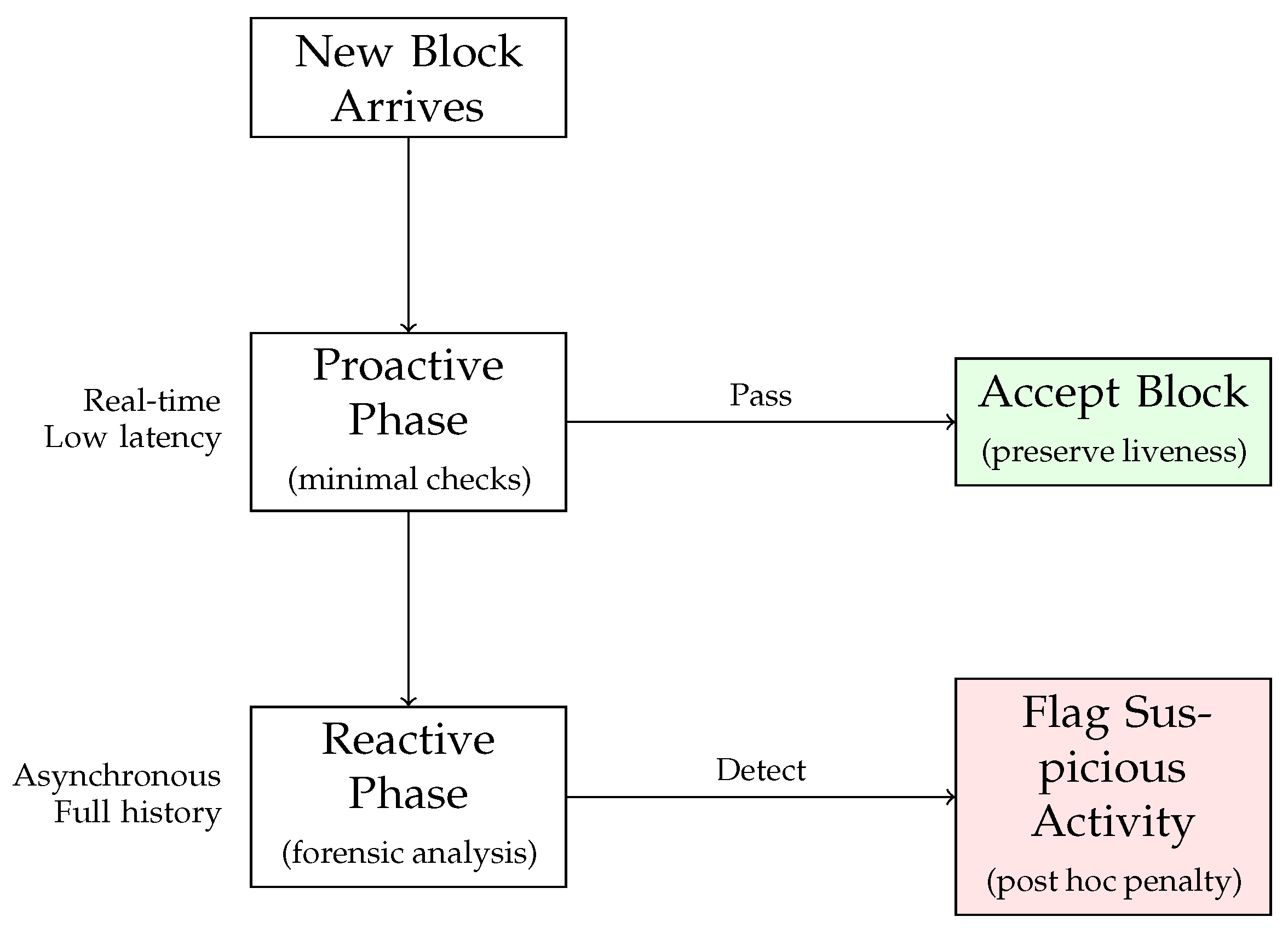

- Separation of liveness from enforcement: Dual-phase architecture that accepts blocks optimistically while performing rigorous forensic analysis asynchronously.

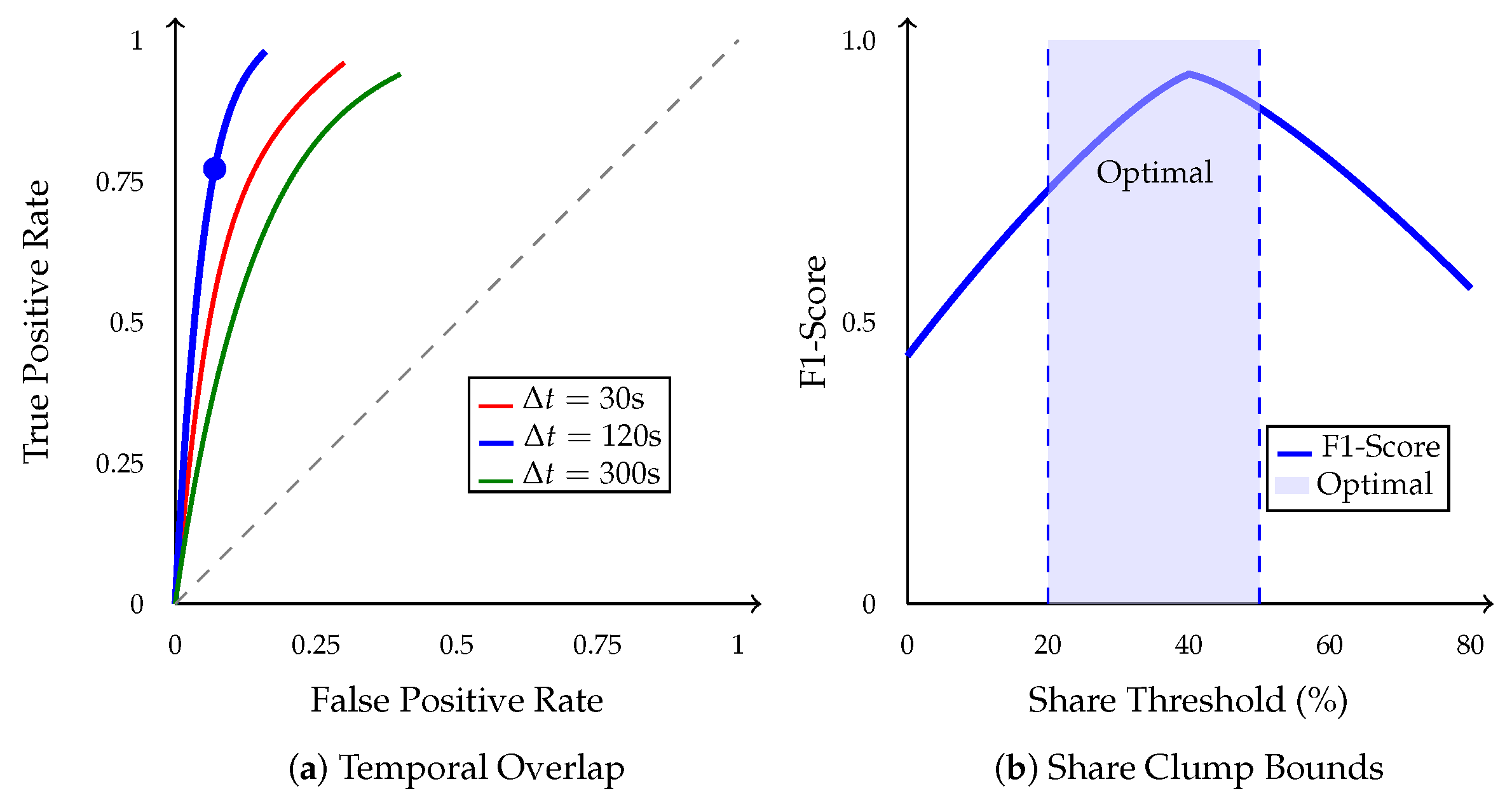

- Controller-aligned detection: Detection windows synchronized to DAA boundaries with physics-informed anomaly statistics.

- Transitive collusion grouping: Union-find algorithm that identifies coordinated attacks through temporal overlap analysis.

- FDR control: Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to bound false positives while maintaining high detection power.

- Economic deterrence with formal proofs: Theorem proving that penalties on unvested rewards make attacks asymptotically unprofitable for rational adversaries.

1.2. Design Philosophy: Prioritizing Liveness over Premature Rejection

1.3. Contributions

- 1.

- Production-ready framework: Complete dual-phase architecture with detailed description of algorithms and deployment experience that can be validated online (‘chain -sec’ command in GRIDNET OS).

- 2.

- Controller-aligned detection: Novel detection methodology synchronized with DAA dynamics for improved accuracy.

- 3.

- Transitive collusion grouping: Union-find based algorithm that identifies coordinated attacks through temporal overlap.

- 4.

- Formal economic deterrence: Theorems proving that penalties on unvested rewards make rational attacks unprofitable.

- 5.

- Comprehensive evaluation: 30-run experiments on 128-node testbed across three blockchain networks.

- 6.

- Limitations analysis: We discuss limitations of static models against adaptive adversaries, motivating the AI-driven enhancements presented in Part II of this series.

1.4. Paper Organization

2. Related Work

3. System Model and Threat Assumptions

3.1. Blockchain Model

3.2. Adversary Model

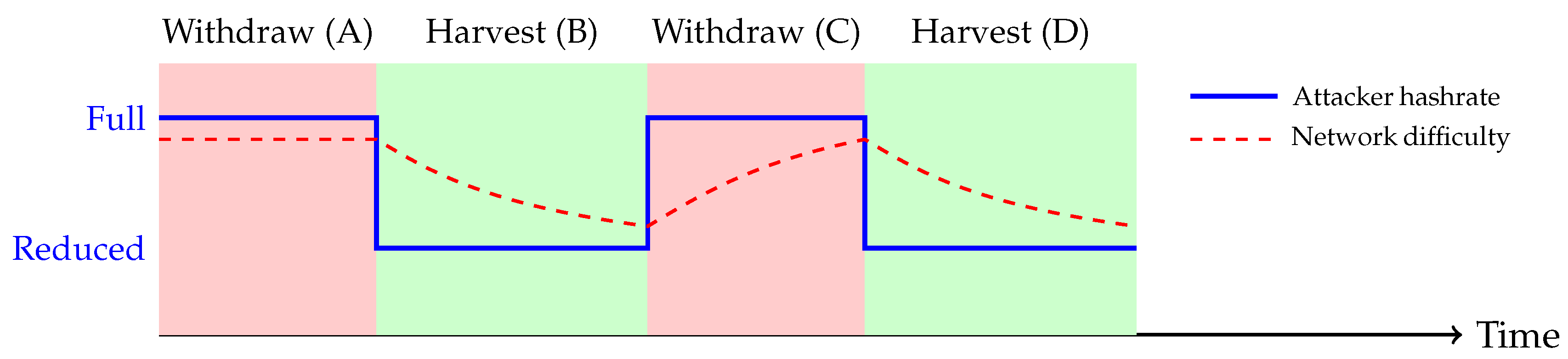

- Withdrawal phase (): Adversary reduces mining to negligible level (≈ of ).

- Harvest phase (): Adversary deploys full capacity ().

- Timing: Phases synchronized to DAA window boundaries to maximize difficulty suppression.

- A1 (Rational): Adversary seeks to maximize expected profit over long time horizons.

- A2 (Observable): All block headers and timestamps are public.

- A3 (Unvested penalties): Governance can forfeit unvested rewards upon detection.

- A4 (Detection lag): Detection occurs within blocks.

3.3. Design Objectives

- 1.

- Liveness: Maintain block production rate; avoid false rejections that stall consensus.

- 2.

- Detection accuracy: Achieve high true positive rate (TPR) while controlling false positive rate (FPR ).

- 3.

- Economic deterrence: Ensure expected attacker payoff is negative:

- 4.

- Fairness: Bound probability of falsely penalizing honest miners via FDR control.

4. Notation and Nomenclature

5. Framework Architecture

- 1.

- Phase 1 (Proactive): Real-time block validation with minimal checks to preserve liveness.

- 2.

- Phase 2 (Reactive): Asynchronous forensic analysis with comprehensive attack detection.

5.1. Phase 1: Proactive Block Validation

5.1.1. Timestamp Verification

| Algorithm 1 Proactive Timestamp Validation |

|

5.1.2. PoW and Difficulty Verification

| Algorithm 2 Proactive PoW Difficulty Validation |

|

5.2. Phase 2: Reactive Chain Analysis

5.2.1. Controller-Aligned Window Maintenance

| Algorithm 3 Detection Window Maintenance |

|

5.2.2. Difficulty-Phase Concentration Detection

| Algorithm 4 Difficulty Phase Concentration Detection |

|

5.2.3. Temporal Overlap Grouping

| Algorithm 5 Temporal Overlap Grouping (Union-Find) |

|

5.2.4. Main Analysis Pipeline

| Algorithm 6 Chain Window Analysis |

|

5.2.5. Timestamp Manipulation Forensics

| Algorithm 7 Block Timestamp Manipulation Analysis |

|

6. Implementation and Evaluation

6.1. Experimental Setup

- Withdrawal phase: Duration (288 blocks). Adversaries reduce mining to 10% capacity.

- Harvest phase: Duration (144 blocks). Adversaries deploy full 100% capacity.

- Cycle period: blocks ≈ 72 h.

6.2. Evaluation Metrics

- Detection performance: Precision, Recall, F1-score, false positive rate (FPR), Area Under Curve (AUC) for ROC analysis

- Adversary profit (%): We define profit percentage relative to honest baseline aswhere ROI (return on investment) is the ratio of rewards earned to expected rewards under proportional mining. A negative profit indicates the attacker loses more than they would earn through honest mining. For example, means the attacker’s losses are 1.5 times their expected honest revenue.

- Profit suppression: Reduction in adversary’s profit relative to honest miner baseline.

- Latency: Average time between attack onset and detection.

7. Results

7.1. Detection Performance

7.2. Ablation Study

7.3. Sensitivity Analysis

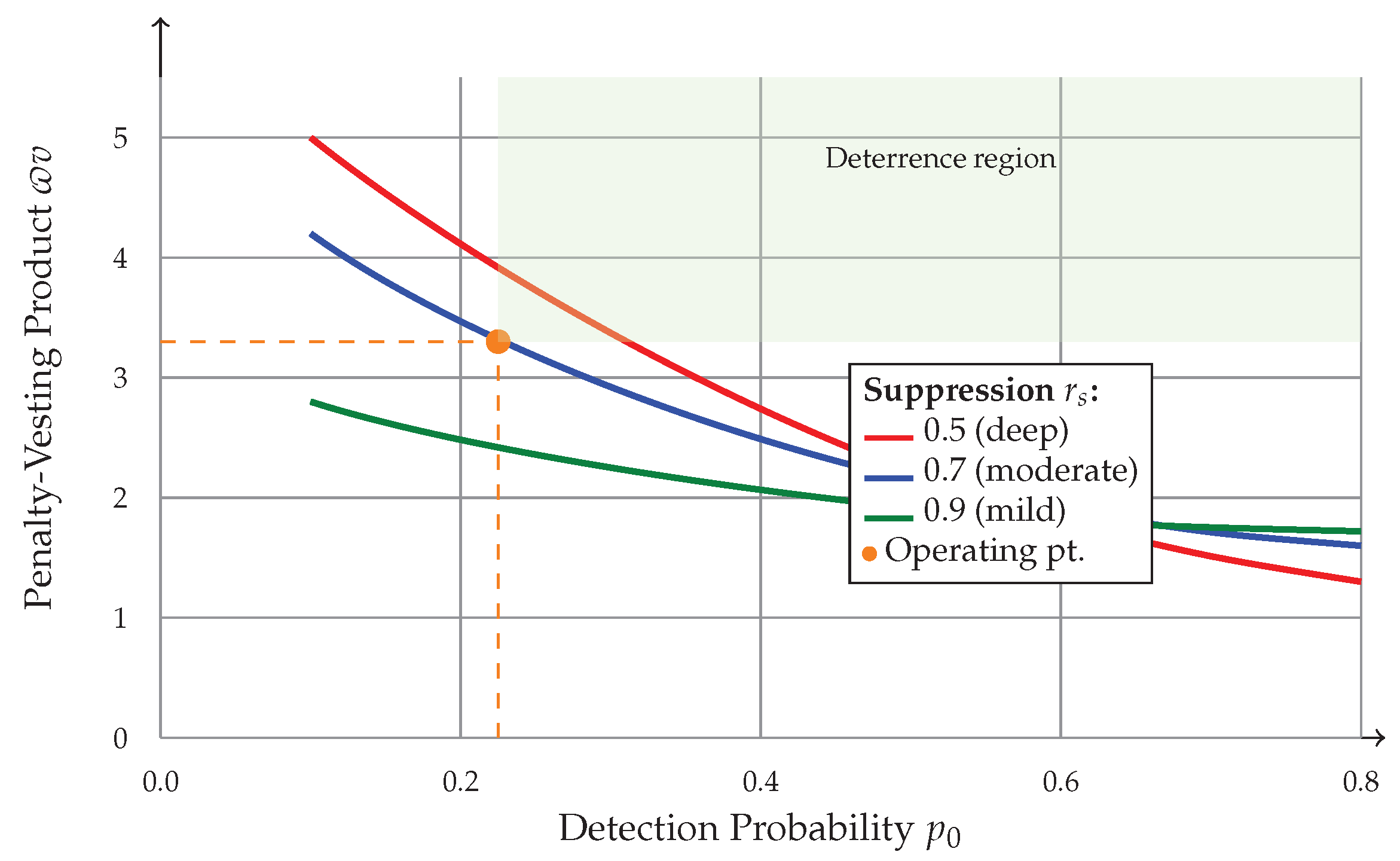

- Deeper difficulty suppression (): requires higher to maintain deterrence due to increased attack profitability.

- Higher detection probability (): significantly reduces required , improving capital efficiency.

- Operating point (, ): a conservative choice providing robustness against parameter uncertainty.

8. Theoretical Validation: Formal Economic Deterrence

8.1. Symbol Definitions for Economic Analysis

- : Expected gain function quantifying profit from reduced difficulty, where is mean difficulty during attack and during honest mining.

- : Number of blocks abstained during withdrawal phase.

- : Fraction of adversarial hashrate temporarily offline during difficulty suppression.

- : Penalty multiplier on unvested rewards (governance parameter, ).

- v: Fraction of rewards unvested at detection time ().

- R: Per-block reward (protocol-specified).

- : Minimum fraction of DAA window exhibiting anomalous behavior for detection ().

- : Lower bound on detection probability per cycle.

- : Difficulty suppression ratio.

8.2. Main Theorem

Intuition: Consider a wave attacker who gains extra blocks through difficulty manipulation (benefit) but faces penalty on unvested rewards when detected (cost). The key insight is that if detection probability is high enough and penalty ϖ is large enough, the expected cost exceeds the benefit. Theorem 1 quantifies the exact threshold where attacks become unprofitable. The proof establishes three key results: (1) detection probability increases with difficulty suppression depth, (2) expected penalties scale with flagged blocks, and (3) rational attackers face negative expected payoff when .

- Detection probability variance: Actual varies with specific attack patterns; using point estimate introduces conservative bias.

- Difficulty suppression estimation: Ratio computed from finite samples with standard error.

- Network dynamics: Transient hashrate fluctuations can temporarily reduce effective detection probability by 5–15%.

- Governance feasibility: Value represents practical compromise between deterrence strength and community acceptability.

- Gain function: has units [reward/block] × [blocks] × [dimensionless] × [dimensionless] = [reward] per cycle. ✓

- Expected loss: has units [dimensionless] × [dimensionless] × [reward/block] × [dimensionless] × [blocks] × [dimensionless] × [dimensionless] = [reward] per cycle. ✓

- Abstention cost: has units [blocks] × [reward/block] = [reward] per cycle. ✓

9. Security Analysis and Limitations

9.1. Robustness

9.2. Limitations and Future Work

9.2.1. Feasibility of Penalty Enforcement

9.2.2. Parameter Selection and Governance Challenges

- 1.

- Community resistance: High penalties may be perceived as authoritarian, creating political friction within decentralized communities. Blockchain governance often prioritizes minimizing intervention, making aggressive penalty regimes difficult to implement.

- 2.

- Optimal parameter uncertainty: The required depends on detection probability , which varies with attack characteristics. Setting too low fails to deter attacks; setting it too high risks over-penalizing honest miners during false positives, eroding trust in the system.

- 3.

- Consensus requirement: Parameter updates require community consensus, which can take months or years. Adversaries can exploit this inertia by adapting faster than governance can respond.

- 4.

- Capital efficiency trade-offs: Longer vesting periods V improve detection window coverage but reduce capital efficiency for honest miners who must wait longer to access rewards. This creates tension between security and economic competitiveness.

9.2.3. Adaptive Adversaries and the Arms Race

- 1.

- Gradual intensity reduction: Slowly decrease attack amplitude over time to stay below detection thresholds while still earning modest excess profits. For example, reducing difficulty suppression from to may halve the detection probability while retaining 30% of attack profits.

- 2.

- Randomized attack patterns: Introduce stochastic variation in withdrawal/harvest phase durations to break temporal correlations that union-find grouping relies on. By decorrelating attack phases across cycles, adversaries can fragment their signature across multiple detection windows.

- 3.

- Threshold probing: Conduct exploratory attacks at varying intensities to map out detection boundaries, then operate just below the threshold. This is analogous to adversarial machine learning attacks where adversaries probe model decision boundaries.

- 4.

- Multi-timescale attacks: Operate across multiple timescales (e.g., mixing short 1-week cycles with long 3-month cycles) to exploit different detection window sizes and confuse statistical aggregators.

- 5.

- Exploiting parameter knowledge: If detection thresholds become public knowledge (as required for transparency in open blockchain governance), adversaries can reverse-engineer optimal attack strategies that maximize profit while minimizing detection risk.

9.2.4. Detection Latency and Vesting Window Constraints

9.2.5. False Positive Impact on Network Stability

9.2.6. Motivating Part II: The Need for Adaptive Defenses

- Continuously adapts detection thresholds based on observed attack patterns;

- Learns optimal penalty schedules dynamically without requiring governance intervention for every adjustment;

- Engages in game-theoretic co-evolution with adaptive adversaries;

- Maintains provable convergence properties while offering superior empirical performance against intelligent attackers.

10. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eyal, I.; Sirer, E.G. Majority is not enough: Bitcoin mining is vulnerable. Commun. ACM 2018, 61, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, K.; Kumar, S.; Miller, A.; Shi, E. Stubborn mining: Generalizing selfish mining and combining with an eclipse attack. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy, Saarbrücken, Germany, 21–24 March 2016; pp. 305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Skowroński, R. The open blockchain-aided multi-agent symbiotic cyber–physical systems. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 94, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowroński, R.; Brzeziński, J. UI dApps meet decentralized operating systems. Electronics 2022, 11, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowroński, R.; Brzeziński, J. SPIDE: Sybil-proof, incentivized data exchange. Cluster Comput. 2022, 25, 2241–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Zur, R.; Eyal, I.; Tamar, A. Undetectable Selfish Mining. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.06847. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Duan, S. Timestamp Manipulation: Timestamp-Based Nakamoto-Style Blockchains are Vulnerable. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.05328. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.N.; Campajola, C.; Tessone, C.J. Statistical detection of selfish mining in proof-of-work blockchain systems. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapirshtein, A.; Sompolinsky, Y.; Zohar, A. Optimal selfish mining strategies in Bitcoin. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 26–30 January 2015; pp. 515–532. [Google Scholar]

- Meshkov, D.; Chepurnoy, A.; Jansen, M. Short Paper: Revisiting Difficulty Control for Blockchain Systems. In Proceedings of the International Workshops on Data Privacy Management, Cryptocurrencies and Blockchain Technology, Barcelona, Spain, 7 September 2017; pp. 429–436. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M.; Liskov, B. Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance. In Proceedings of the 3rd Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 22–25 February 1999; pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Buterin, V.; Hernandez, D.; Kamphefner, T.; Pham, K.; Qiao, Z.; Ryan, D.; Sin, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.X. Combining GHOST and Casper. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.03052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiayias, A.; Koutsoupias, E.; Kyropoulou, M.; Tselekounis, Y. Blockchain mining games. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Economics and Computation, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 24–28 July 2016; pp. 365–382. [Google Scholar]

- Skowroński, R. Adaptive threat mitigation in PoW blockchains (Part II): A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach to Countering Evasive Adversaries. Poznan University of Technology: Poznań, Poland, 2025; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Symbol | Definition | Typical Value/Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network and System | N | Set of all nodes in the network | – |

| M | Set of mining operators () | – | |

| H | Total network hashrate | Variable | |

| W | DAA window size (blocks) | 144 blocks (testbed) | |

| T | Target inter-block interval | 600 s (GRIDNET) | |

| k | Confirmation depth | 6 blocks | |

| Block arrival rate () | Variable | ||

| Attack and Detection | Adversary’s hashrate fraction | ||

| Fraction of hashrate offline | Temporary withdrawal | ||

| S | Adversarial coalition set () | – | |

| Anomaly threshold parameter | 0.5 | ||

| Time overlap window for collusion | 120 s | ||

| Minimum fraction of anomalous window | |||

| Detection probability lower bound | Protocol-dependent | ||

| Probability of flagging attack window | ≥ | ||

| Single-block anomaly probability | Derived | ||

| Economic and Penalty | R | Per-block reward | Protocol-specific |

| v | Vesting fraction (unvested) | ||

| V | Vesting period (blocks) | Must exceed D | |

| D | Detection latency (blocks) | <V | |

| Penalty multiplier when armed | ≥ | ||

| L | Expected lost reward per cycle | Variable | |

| Number of blocks abstained | Integer | ||

| Difficulty and Mining | D | Network difficulty | Time-varying |

| Average difficulty | Time-averaged | ||

| Honest average difficulty | Baseline | ||

| Attack average difficulty | Suppressed | ||

| Difficulty suppression ratio | |||

| Suppressed difficulty | |||

| Gross wave gain function | Exploitation gain | ||

| Statistical Measures | Mean inter-block time | Window-specific | |

| Standard deviation | Window-specific | ||

| Z-score for operator o | Anomaly metric | ||

| False Discovery Rate target | 0.05 | ||

| FDR | Empirical False Discovery Rate | ≤ | |

| TPR | True positive rate (Recall) | Detection metric | |

| FPR | False positive rate | Type I error | |

| AUC | Area Under ROC Curve | Model quality | |

| EWMA | Exponentially Weighted Moving Average | Smoothing | |

| Attack Phases | Withdrawal phase duration | blocks | |

| Harvest phase duration | W blocks | ||

| Full attack cycle period | blocks | ||

| Expected value operator | Probability theory |

| Network | Precision | Recall | F1 | FPR | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bitcoin | 96.6 (±1.2) | 89.2 (±2.1) | 92.7 (±1.4) | 3.4 (±0.8) | 0.967 |

| 95% CI: [96.2, 97.0], [88.4, 90.0], [91.2, 94.1], [3.1, 3.7], [0.958, 0.976] | |||||

| ETC | 95.0 (±1.5) | 91.5 (±1.8) | 93.2 (±1.3) | 4.9 (±1.1) | 0.953 |

| 95% CI: [94.5, 95.5], [90.8, 92.2], [92.7, 93.7], [4.5, 5.3], [0.941, 0.965] | |||||

| Monacoin | 95.8 (±1.3) | 95.8 (±1.6) | 95.8 (±1.2) | 4.2 (±0.9) | 0.979 |

| 95% CI: [95.3, 96.3], [95.2, 96.4], [95.3, 96.3], [3.9, 4.5], [0.972, 0.986] | |||||

| Baseline | 78.3 (±2.8) | 71.5 (±3.2) | 74.7 (±2.6) | 21.7 (±3.5) | 0.749 |

| 95% CI: [77.2, 79.4], [70.3, 72.7], [71.5, 77.8], [20.2, 23.2], [0.732, 0.766] | |||||

| Configuration | Prec | Recall | F1 | FPR | g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Framework | 96.6 | 89.2 | 92.7 | 3.4 | – |

| w/o Union-Find | 96.2 | 65.8 | 78.0 | +0.4 | 6.21 |

| : −14.7 F1; | |||||

| w/o Cooldown | 78.4 | 88.5 | 83.1 | +10.9 | 4.18 |

| : −9.6 F1; | |||||

| w/o Difficulty Feat. | 95.8 | 69.1 | 80.3 | +0.8 | 5.73 |

| : −12.4 F1; | |||||

| w/o FDR Control | 85.2 | 91.3 | 88.1 | +14.6 | 2.94 |

| : −4.6 F1; | |||||

| Variance Only | 78.3 | 71.5 | 74.7 | +18.3 | 7.84 |

| : −18.0 F1; | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skowroński, R. Liveness over Fairness (Part I): A Statistically Grounded Framework for Detecting and Mitigating PoW Wave Attacks. Information 2025, 16, 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121060

Skowroński R. Liveness over Fairness (Part I): A Statistically Grounded Framework for Detecting and Mitigating PoW Wave Attacks. Information. 2025; 16(12):1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121060

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkowroński, Rafał. 2025. "Liveness over Fairness (Part I): A Statistically Grounded Framework for Detecting and Mitigating PoW Wave Attacks" Information 16, no. 12: 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121060

APA StyleSkowroński, R. (2025). Liveness over Fairness (Part I): A Statistically Grounded Framework for Detecting and Mitigating PoW Wave Attacks. Information, 16(12), 1060. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121060