A Systems Approach to Validating Large Language Model Information Extraction: The Learnability Framework Applied to Historical Legal Texts

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Information Extraction Validation: Current Approaches and Limitations

1.2. Large Language Models in Information Extraction: Opportunities and Challenges

1.3. Systems Theory and Information Extraction Validation

1.4. Research Objectives and Contributions

- RQ1: How can the internal consistency of LLM-based IE be quantitatively measured as a systemic property in the absence of ground-truth annotations?

- RQ2: Does this proposed validation system provide robust empirical evidence of systematic, semantically coherent IE when applied to historical legal texts?

- RQ3: What are the implications of using such a framework for enhancing the reliability of AI-assisted IE in computational research?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Corpus and Information Extraction Task Definition

2.1.1. Historical Legal Corpus

2.1.2. Information Extraction Schema Design

2.2. Large Language Model Information Extraction System

2.2.1. LLM Architecture and Selection

2.2.2. Prompt Engineering for Information Extraction

2.2.3. Information Extraction Implementation

2.3. The Learnability Framework for Information Extraction Validation

2.3.1. Theoretical Foundation: Distinguishing Learnability from Cross-Validation

2.3.2. Implementation of Internal Validation

2.4. External Multi-Method Validation

2.4.1. Multi-LLM Information Extraction Comparison

2.4.2. Human Expert Validation Protocol

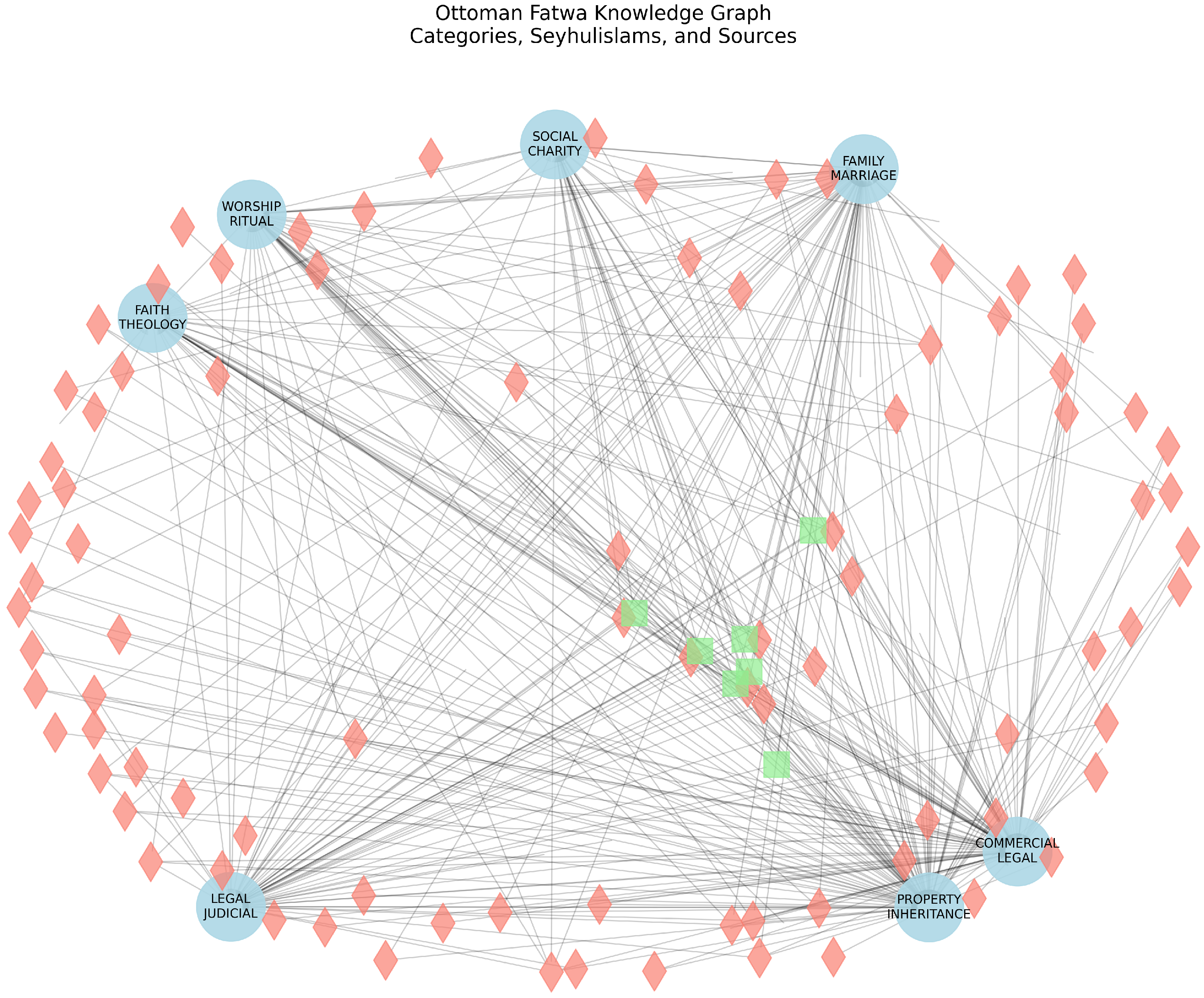

2.5. Knowledge Graph Construction from Validated Extractions

3. Results

3.1. Information Extraction System Performance and Statistical Robustness

3.2. External Validation: Comprehensive Multi-LLM Comparison

3.2.1. Model Selection and Architectural Diversity

- Claude-3.5-Sonnet (Anthropic): Our primary extraction model

- DeepSeek-Reasoner: Reasoning-optimized architecture

- GPT-4 (OpenAI): Different transformer variant

- Gemini-Pro (Google): Multimodal foundation model

- Llama-3.1-70B (Meta): Open-weight model

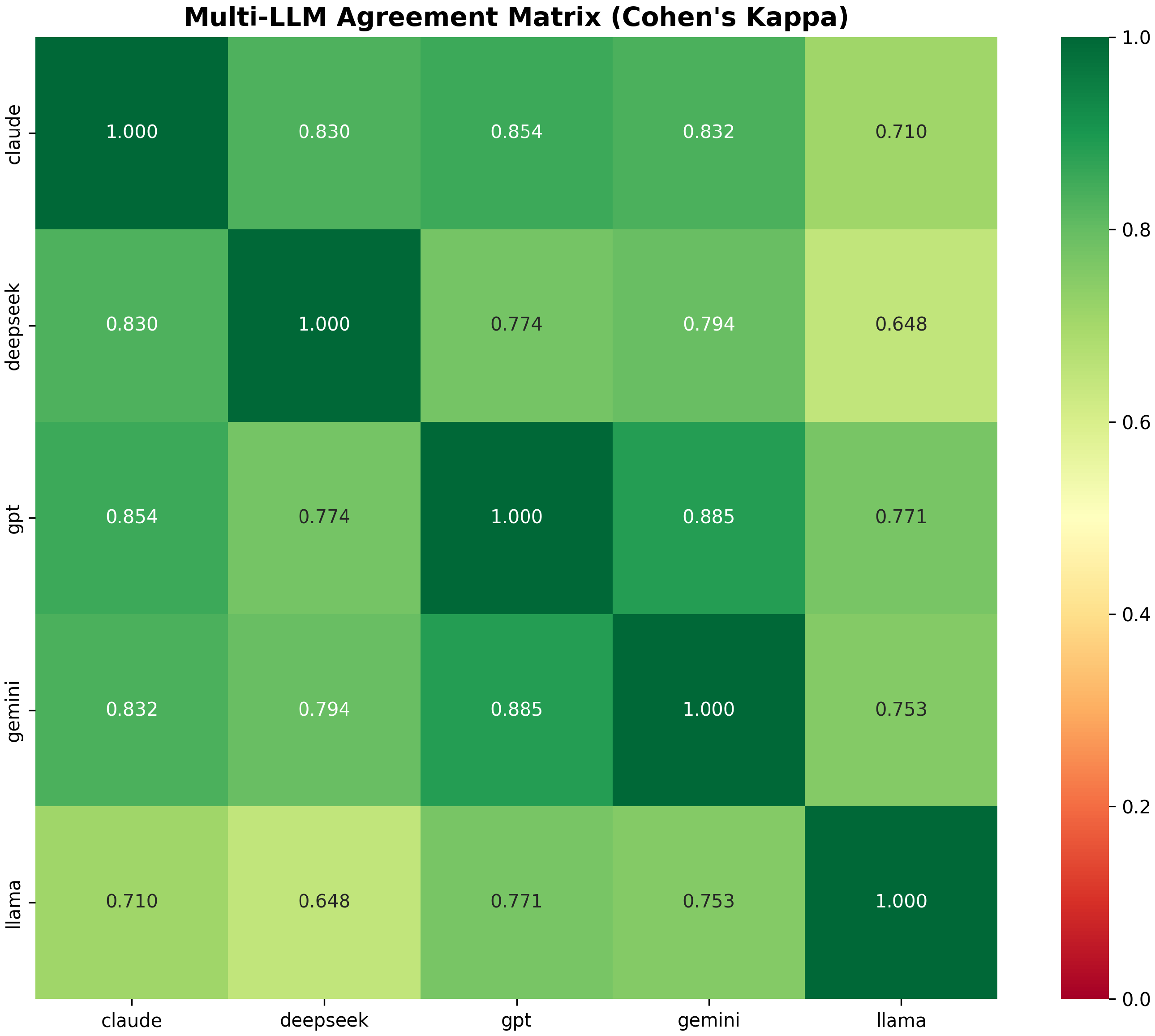

3.2.2. Quantitative Agreement Analysis

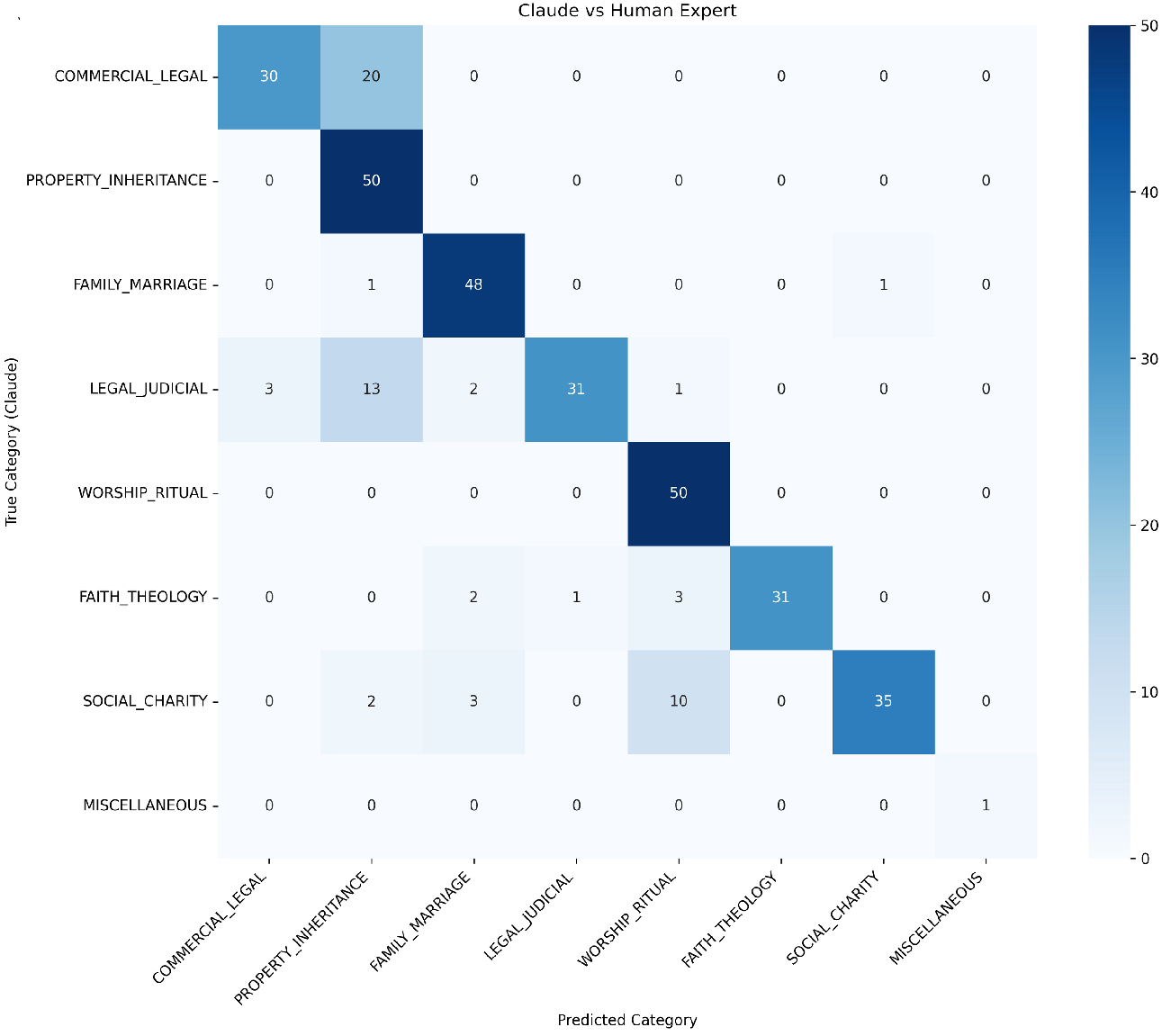

3.2.3. Confusion Pattern Analysis Across Models

3.3. Error Analysis: Semantic Coherence in Classification Disagreements

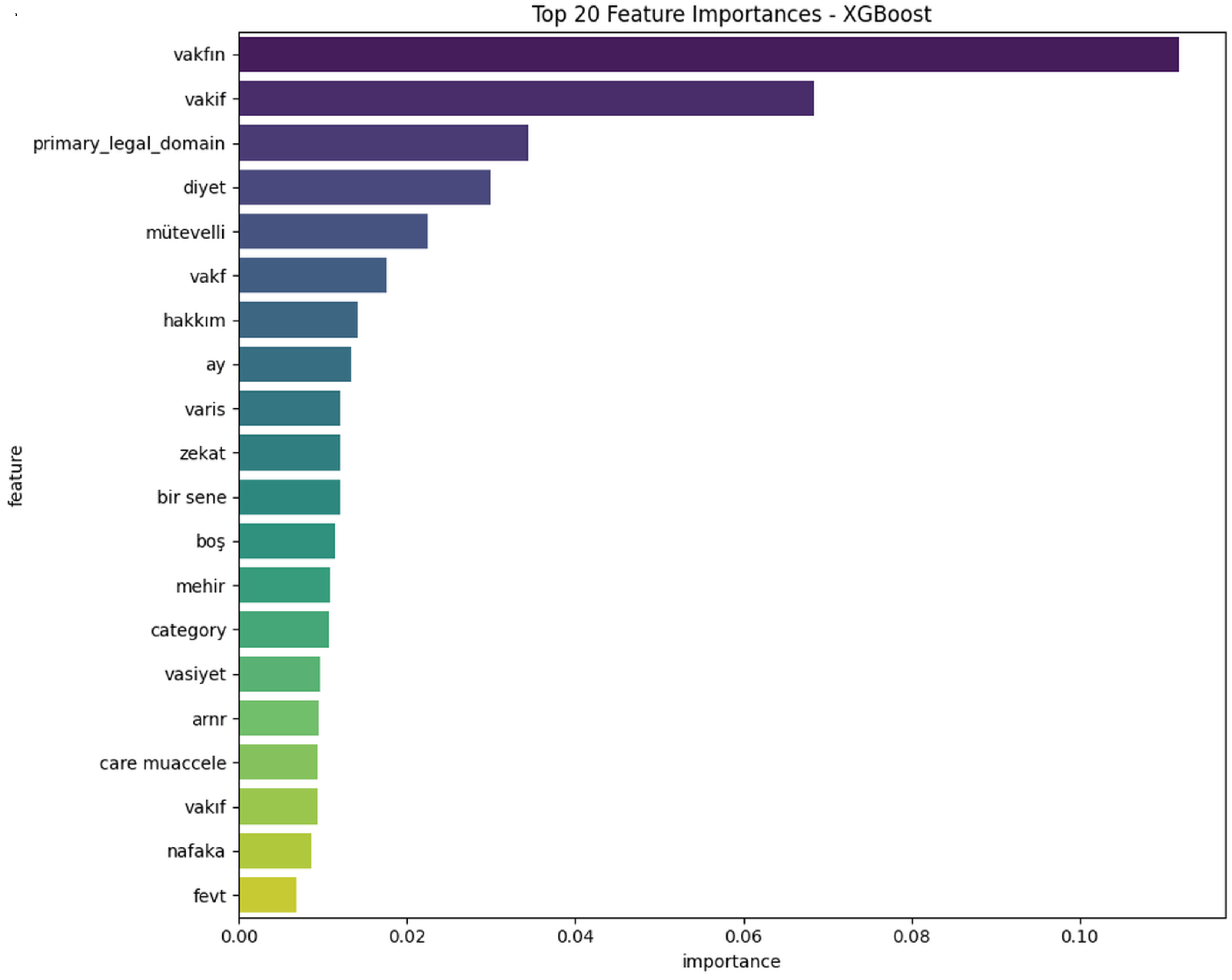

3.4. Feature Importance Analysis: Linguistic Validation

3.5. Human Expert Validation

3.6. Learning Curve Analysis: Evidence of Data Quality

3.7. Cost-Effectiveness and Scalability

- Total cost: USD 200 for 20,809 documents (USD 0.01 per document).

- Processing time: 5 s per document (parallelizable).

- Total time: 28.9 h (reducible with parallelization).

4. Discussion

4.1. Validation Without Ground Truth: A Paradigm Shift

4.2. Comparison with Prior Validation Methods

4.3. Implications for Knowledge Graph Construction

4.4. Limitations and Boundary Conditions

4.5. Practical Implementation Guidelines

- Learnability Score () > 0.85: High-quality extraction.

- = 0.70–0.85: Moderate quality requiring targeted review.

- < 0.70: Systematic issues requiring revision.

- > 0.75: Sufficient agreement for research applications.

- = 0.60–0.75: Acceptable with acknowledged limitations.

- < 0.60: Inadequate reliability requiring redesign.

5. Conclusions

- Primary contributions:

- (i)

- A systems-based validation paradigm that provides scalable, model-agnostic quality assessment without ground truth.

- (ii)

- Comprehensive multi-LLM validation demonstrating robust cross-model consensus across diverse architectures.

- (iii)

- Detailed error analysis revealing semantically meaningful confusion patterns that reflect genuine domain ambiguity.

- (iv)

- Practical implementation guidelines with cost-efficiency metrics (USD 0.01 per document).

- (v)

- An explicit pathway to knowledge graphs using validated labels as high-confidence anchors.

- Broader Impact:

- Future Directions:

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Large Language Model Information Extraction Prompt

You are an expert in information extraction from legal documents and Islamic jurisprudence classification. Your task is to perform structured information extraction on Ottoman fatwa records, categorizing them into predefined legal domains to create machine-readable knowledge representations.

INFORMATION EXTRACTION TASK: Extract the primary legal domain from each fatwa document by analyzing both explicit terminological markers and implicit contextual ↪ cues.

TARGET CATEGORIES (Choose ONE): - COMMERCIAL_LEGAL: All commercial transactions, trade, property rights, financial dealings, business partnerships, rentals, agency relationships. Keywords: trade, sales, finance, rental, partnership, property rights, land, agency, trust, icare, bey, şirket, vekalet - PROPERTY_INHERITANCE: Inheritance law, wills, endowments (waqf), religious foundations, property transfer through inheritance or donation. Keywords: inheritance, wills, waqf, endowment, miras, vakıf, hibe, vasiyet - FAMILY_MARRIAGE: Marriage contracts, marital rights, divorce procedures, family relationships, spousal obligations. Keywords: marriage, divorce, family, spouse, nikâh, talak, zevc/zevce, family ↪ rights - LEGAL_JUDICIAL: Court procedures, legal evidence, criminal law, judicial processes, legal rights, punishment. Keywords: court, evidence, criminal, qisas, hudud, judge, şahit, dava, mahkeme - WORSHIP_RITUAL: Daily prayers, congregational prayers, pilgrimage, fasting, purification, ritual worship practices. Keywords: prayer, fasting, pilgrimage, purification, namaz/salat, oruç, hac, ↪ abdest - FAITH_THEOLOGY: Religious beliefs, theological questions, matters of faith, destiny, core Islamic doctrines. Keywords: faith, belief, theology, destiny, iman, akaid, kader - SOCIAL_CHARITY: Charitable obligations, social ethics, community ↪ responsibilities, food regulations, zakat. Keywords: charity, ethics, zakat, social conduct, sadaka, ahlak, food, drink

CLASSIFICATION PRIORITY HIERARCHY: 1. COMMERCIAL_LEGAL (if involves business/property transactions) 2. PROPERTY_INHERITANCE (if involves inheritance/waqf/property transfer) 3. FAMILY_MARRIAGE (if involves marital/family relationships) 4. LEGAL_JUDICIAL (if involves court procedures/criminal matters) 5. WORSHIP_RITUAL (if involves religious practices/rituals) 6. FAITH_THEOLOGY (if involves beliefs/theological questions) 7. SOCIAL_CHARITY (if involves social ethics/charitable obligations)

OUTPUT FORMAT:

Respond with a valid JSON object containing exactly this field:

{

"ew_category": "CATEGORY_NAME"

}

CRITICAL: Your response must be ONLY valid JSON. No explanations, no additional ↪ text, no markdown formatting.

References

- Sarawagi, S. Information extraction. Found. Trends Databases 2008, 1, 261–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, A.; Cafarella, M.; Banko, M.; Etzioni, O.; Broadhead, M.; Soderland, S. TextRunner: Open information extraction on the Web. In Proceedings of the Human Language Technologies: The Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Rochester, NY, USA, 22–27 April 2007; pp. 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Rodriguez, J.L.; Hogan, A.; Lopez-Arevalo, I. Information extraction meets the Semantic Web: A survey. Semant. Web 2020, 11, 255–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Li, Q.; Sun, L.; Peng, W.; Liu, P. Large Language Models for Information Extraction: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.12563. [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa, S.; Amir, S.; Wallace, B.C. Revisiting relation extraction in the era of large language models. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; pp. 15566–15589. [Google Scholar]

- Gilardi, F.; Alizadeh, M.; Kubli, M. ChatGPT outperforms crowd-workers for text-annotation tasks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2305016120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A.; Vashisht, S.; Penha, G.; Beirami, A. LLMs Accelerate Annotation for Medical Information Extraction. In Proceedings of the Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning, New York, NY, USA, 11–13 April 2023; pp. 82–100. [Google Scholar]

- Aroyo, L.; Welty, C. Truth Is a Lie: Crowd Truth and the Seven Myths of Human Annotation. AI Mag. 2015, 36, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İmber, C. Ebu’s-su’ud: The Islamic Legal Tradition; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pustejovsky, J.; Stubbs, A. Natural Language Annotation for Machine Learning; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Artstein, R.; Poesio, M. Inter-coder agreement for computational linguistics. Comput. Linguist. 2008, 34, 555–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, B. The “Problem” of Human Label Variation: On Ground Truth in Data, Modeling and Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; pp. 10671–10682. [Google Scholar]

- Appelt, D.E.; Hobbs, J.R.; Bear, J.; Israel, D.; Tyson, M. FASTUS: A finite-state processor for information extraction from real-world text. In Proceedings of the 13th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Chambéry, France, 28 August–3 September 1993; pp. 1172–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, R.; O’Connor, B.; Jurafsky, D.; Ng, A.Y. Cheap and fast-but is it good? Evaluating non-expert annotations for natural language tasks. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–27 October 2008; pp. 254–263. [Google Scholar]

- Ratner, A.; Sa, C.D.; Wu, S.; Selsam, D.; Ré, C. Data programming: Creating large training sets, quickly. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016; pp. 3567–3575. [Google Scholar]

- Ratner, A.; Bach, S.H.; Ehrenberg, H.; Fries, J.; Wu, S.; Ré, C. Snorkel: Rapid training data creation with weak supervision. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2017, 11, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northcutt, C.G.; Jiang, L.; Chuang, I.L. Confident Learning: Estimating Uncertainty in Dataset Labels. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2021, 70, 1373–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swayamdipta, S.; Schwartz, R.; Lourie, N.; Wang, Y.; Hajishirzi, H.; Smith, N.A.; Choi, Y. Dataset Cartography: Mapping and Diagnosing Datasets with Training Dynamics. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 9275–9293. [Google Scholar]

- Toneva, M.; Sordoni, A.; des Combes, R.T.; Trischler, A.; Bengio, Y.; Gordon, G.J. An Empirical Study of Example Forgetting During Deep Neural Network Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, M.; Ganguli, S.; Dziugaite, G.K. Deep learning on a data diet: Finding important examples early in training. In Proceedings of the 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Online, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 20596–20607. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A Survey of Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.18223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Chalkidis, I.; Fergadiotis, M.; Malakasiotis, P.; Aletras, N.; Androutsopoulos, I. LEGAL-BERT: The Muppets straight out of Law School. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 2898–2904. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Pleiss, G.; Sun, Y.; Weinberger, K.Q. On Calibration of Modern Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 1321–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Taşdemir, E.F.B.; Tandoğan, Z.; Akansu, S.D.; Kızılırmak, F.; Şen, U.; Akca, A.; Kuru, M.; Yanıkoğlu, B. Automatic Transcription of Ottoman Documents Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR), Athens, Greece, 30–31 August 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Yuan, W.; Fu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Hayashi, H.; Neubig, G. Pre-train, Prompt, and Predict: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Methods in Natural Language Processing. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Valiant, L.G. A Theory of the Learnable. Commun. ACM 1984, 27, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgündüz, A. Şeyhülislam Ebüssuüd Efendi Fetvaları; Osmanlı Araştırmaları Vakfı: Istanbul, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cebeci, İ. Ceride-i İlmiyye Fetvaları; Klasik Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Demirtaş, H.N. Açıklamalı Osmanlı Fetvaları: Fetâvâ-yi Ali Efendi; Kubbealtı Neşriyatı: Istanbul, Turkey, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Efendi, A.; el-Gedûsî, H.M.b.A. Neticetü’l-Fetava; Kaya, S., Algın, B., Çelikçi, A.N., Kaval, E., Eds.; Klasik Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, S. Fetāvâ-yı Feyziye; Klasik Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, S.; Algın, B.; Trabzonlu, Z.; Erkan, A. Behcetü’l-Fetava; Klasik Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, S.; Toprak, E.; Kaval Koss, N.; Mercan, Z. Câmiu’l-Icareteyn; Klasik Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Anthropic. Introducing Claude 3.5 Sonnet. 2025. Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-5-sonnet (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 36th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022; pp. 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, M. Cross-Validatory Choice and Assessment of Statistical Predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1974, 36, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeepSeek AI. DeepSeek-V2 and DeepSeek-Coder-V2 Technical Report. 2025. Available online: https://deepseek.com/research (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Hripcsak, G.; Rothschild, A.S. Agreement, the f-measure, and reliability in information retrieval. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2005, 12, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Domain | Description | Key Linguistic Markers |

|---|---|---|

| COMMERCIAL_LEGAL | Commercial transactions, property rights, financial dealings, business partnerships | trade, sales, finance, rental, partnership, property rights, land, agency, trust, icare, bey, şirket, vekalet |

| PROPERTY_INHERITANCE | Inheritance law, wills, endowments (waqf), property transfer through inheritance or donation | inheritance, wills, waqf, endowment, miras, vakıf, hibe, vasiyet |

| FAMILY_MARRIAGE | Marriage contracts, marital rights, divorce procedures, family relationships, spousal obligations | marriage, divorce, family, spouse, nikâh, talak, zevc/zevce, family rights |

| LEGAL_JUDICIAL | Court procedures, legal evidence, criminal law, judicial processes, legal rights, punishment | court, evidence, criminal, qisas, hudud, judge, şahit, dava, mahkeme |

| WORSHIP_RITUAL | Daily prayers, congregational prayers, pilgrimage, fasting, purification, ritual worship practices | prayer, fasting, pilgrimage, purification, namaz/salat, oruç, hac, abdest |

| FAITH_THEOLOGY | Religious beliefs, theological questions, matters of faith, destiny, core Islamic doctrines | faith, belief, theology, destiny, iman, akaid, kader |

| SOCIAL_CHARITY | Charitable obligations, social ethics, community responsibilities, food regulations, zakat | charity, ethics, zakat, social conduct, sadaka, ahlak, food, drink |

| Model | Test Accuracy | Test F1-Macro | CV Mean (F1) | CV Std (F1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.9565 | 0.9452 | 0.9459 | 0.0091 |

| SVM | 0.9389 | 0.9151 | 0.9112 | 0.0049 |

| Random Forest | 0.9291 | 0.8833 | 0.8965 | 0.0166 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.8810 | 0.8187 | 0.8247 | 0.0122 |

| Claude | DeepSeek | GPT-4 | Gemini | Llama | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claude | 1.000 | ||||

| DeepSeek | 0.830 | 1.000 | |||

| GPT-4 | 0.854 | 0.774 | 1.000 | ||

| Gemini | 0.832 | 0.794 | 0.885 | 1.000 | |

| Llama | 0.710 | 0.648 | 0.771 | 0.753 | 1.000 |

| Average | 0.807 | 0.762 | 0.821 | 0.816 | 0.720 |

| ID | Ottoman Text (Excerpt) | English Translation | Classifications | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAMIUL_0576 | “sahib-i arz ol değirmen ocağını tapu ile Bekir’e verip…” | (The landowner gave the mill site to Bekir with title deed…) | Claude: COMMERCIAL Others: PROPERTY | Contains both transactional and property transfer elements |

| CAMIUL_1073 | “Zeyd tarlasını şu kadar akçe bedel mukabelesinde…” | (Zeyd [transferred] his field for such amount of akçe…) | Claude: COMMERCIAL Others: PROPERTY | Combines sale, property transfer, and inheritance aspects |

| Method | Ground Truth | Scalability | Domain-Agnostic | Interpretable | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Standard | Required | Low | Yes | High | High |

| Crowdsourcing | Created | High | Limited | Medium | Medium |

| Weak Supervision | Partial | High | Yes | Low | Low |

| Learnability (Ours) | Not Required | High | Yes | High | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Çetinkaya, A. A Systems Approach to Validating Large Language Model Information Extraction: The Learnability Framework Applied to Historical Legal Texts. Information 2025, 16, 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110960

Çetinkaya A. A Systems Approach to Validating Large Language Model Information Extraction: The Learnability Framework Applied to Historical Legal Texts. Information. 2025; 16(11):960. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110960

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇetinkaya, Ali. 2025. "A Systems Approach to Validating Large Language Model Information Extraction: The Learnability Framework Applied to Historical Legal Texts" Information 16, no. 11: 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110960

APA StyleÇetinkaya, A. (2025). A Systems Approach to Validating Large Language Model Information Extraction: The Learnability Framework Applied to Historical Legal Texts. Information, 16(11), 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16110960