Knowledge Integrity in Large Language Models: A State-of-The-Art Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Questions

- 1.

- RQ1: What techniques are currently used to ensure information and knowledge integrity in Large Language Models (LLMs)?

- 2.

- RQ2: How does knowledge distillation contribute to preserving integrity in LLMs?

- 3.

- RQ3: What approaches are proposed to safeguard semantic integrity in LLM outputs?

- 4.

- RQ4: What methods are employed to implement provenance tracking in LLMs?

1.2. Contributions of This Review

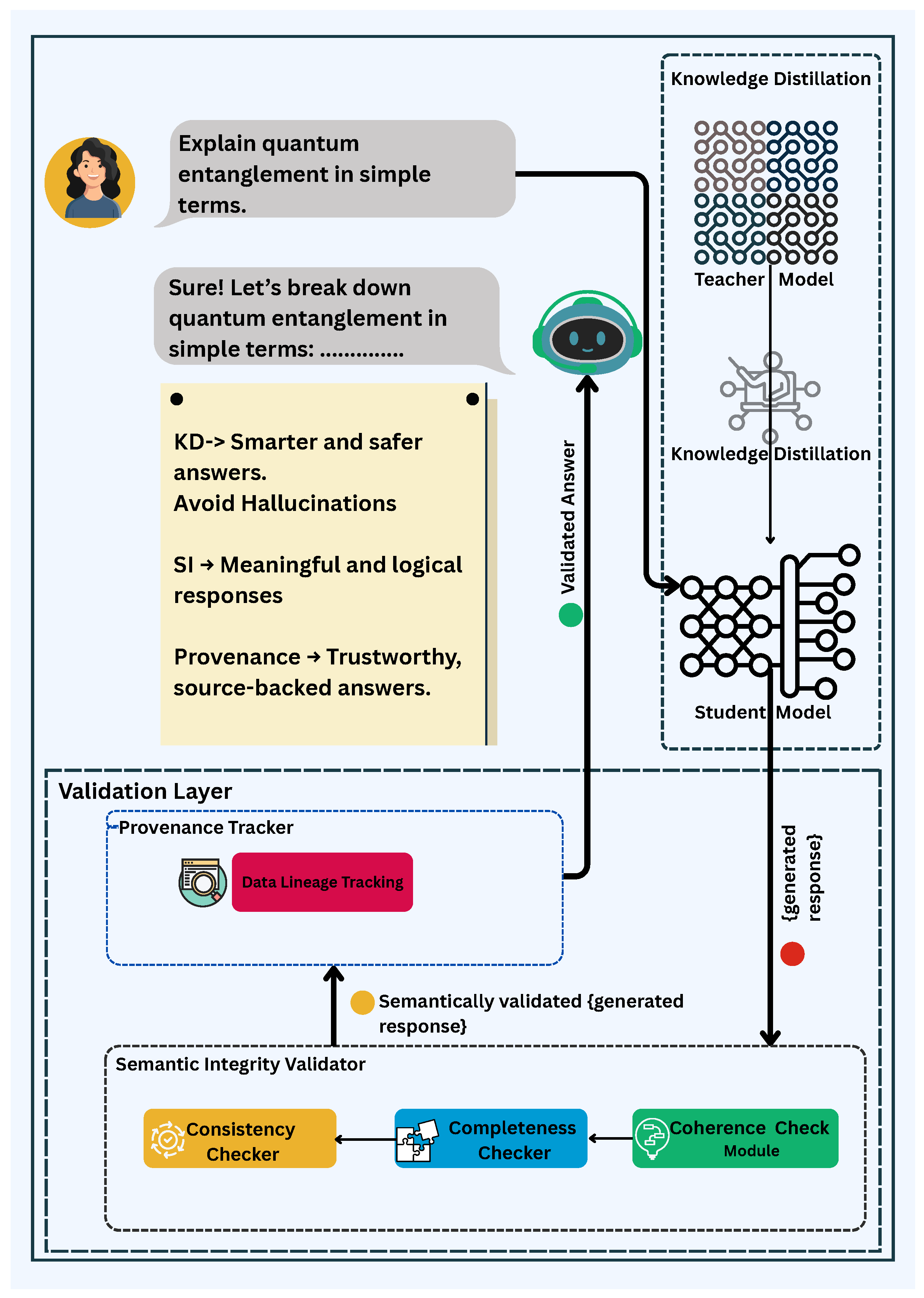

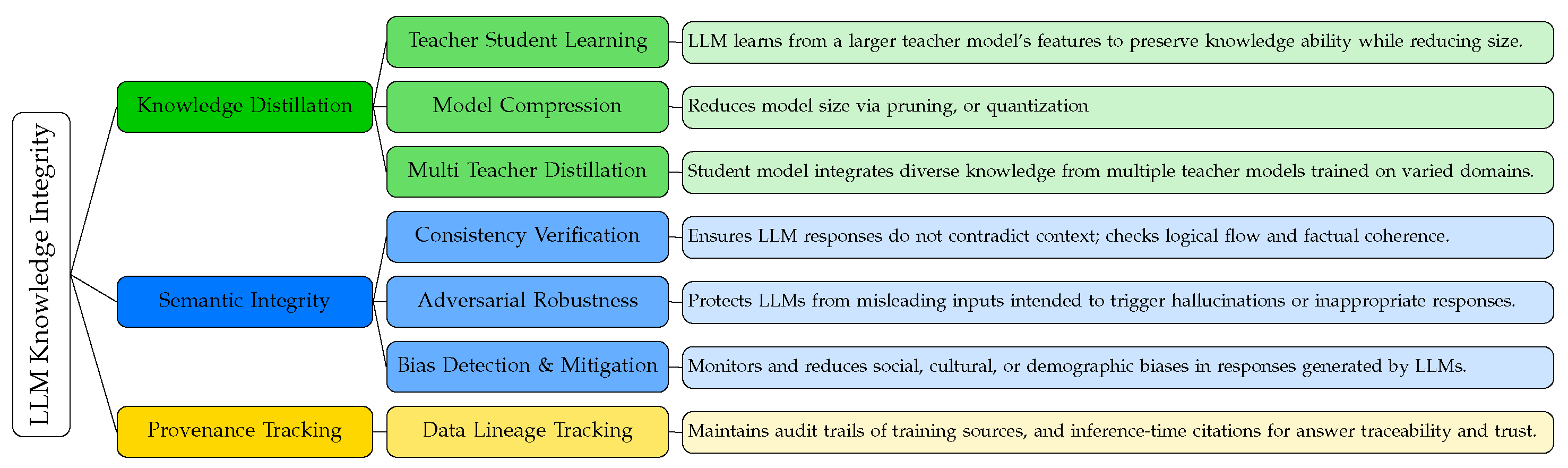

- A comprehensive taxonomy of LLM information and knowledge integrity, focusing on knowledge distillation, semantic integrity, and provenance tracking.

- An analysis of knowledge distillation techniques to promote hallucination-free and content-aware responses in smaller LLMs.

- An examination of semantic integrity and provenance tracking approaches to mitigate threats, ensure legitimate outputs, and enhance the authenticity and traceability of LLM-generated content.

2. Background

2.1. General Overview

2.1.1. Large Language Models

2.1.2. Information Security in Large Language Models

2.1.3. Knowledge Management in Large Language Models

2.1.4. Integrity in LLM Context

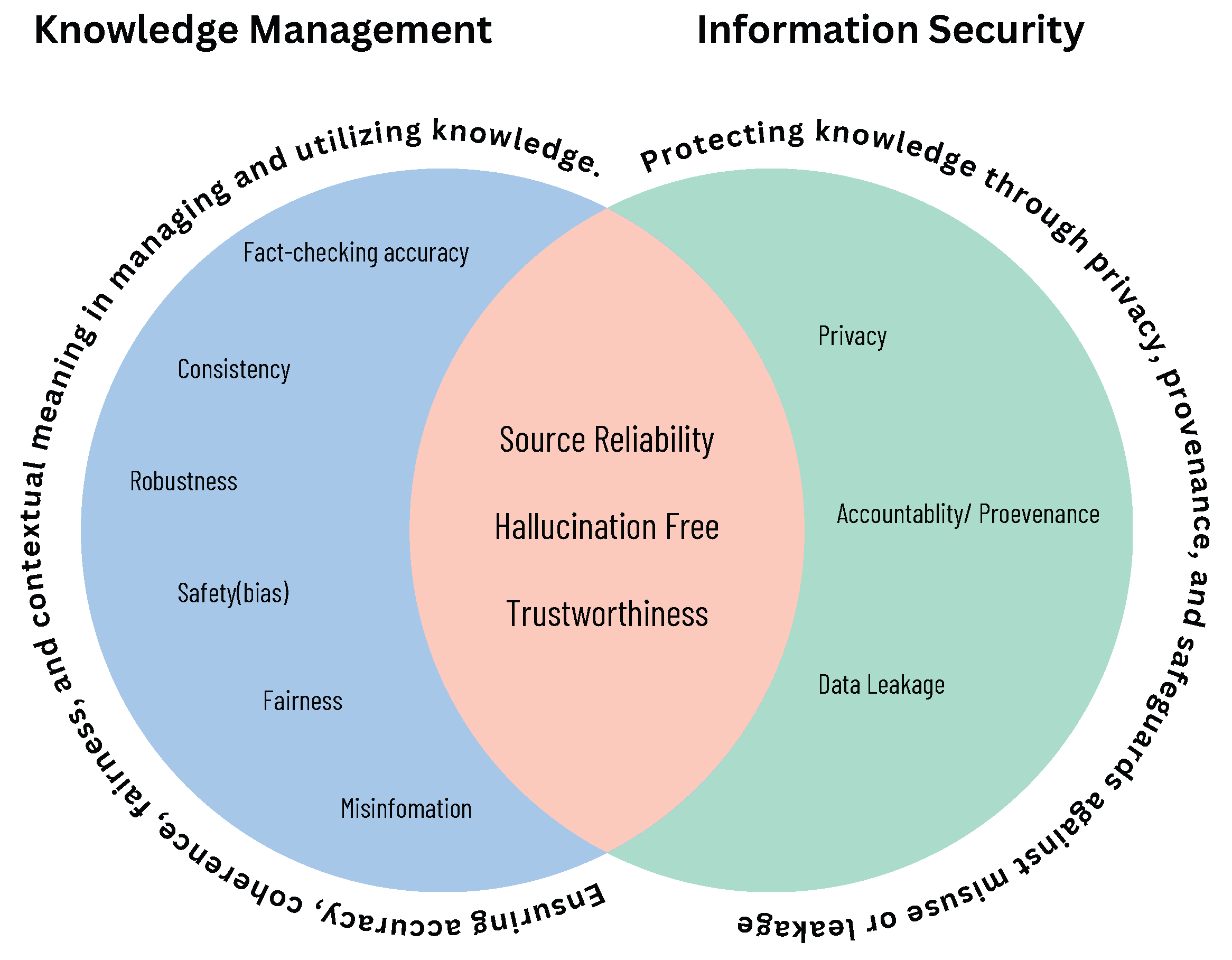

2.1.5. Bridging Knowledge Management and Information Security

2.1.6. Knowledge Distillation

2.1.7. Semantic Integrity

2.1.8. Provenance Tracking in LLMs

2.2. Framework for Knowledge Integrity

3. Comparison with Existing Work

- Knowledge Distillation: Improving model efficiency while retaining performance.

- Semantic Integrity: Ensuring the consistency and correctness of generated outputs.

- Provenance Tracking: Enhancing traceability and accountability in model training and usage.

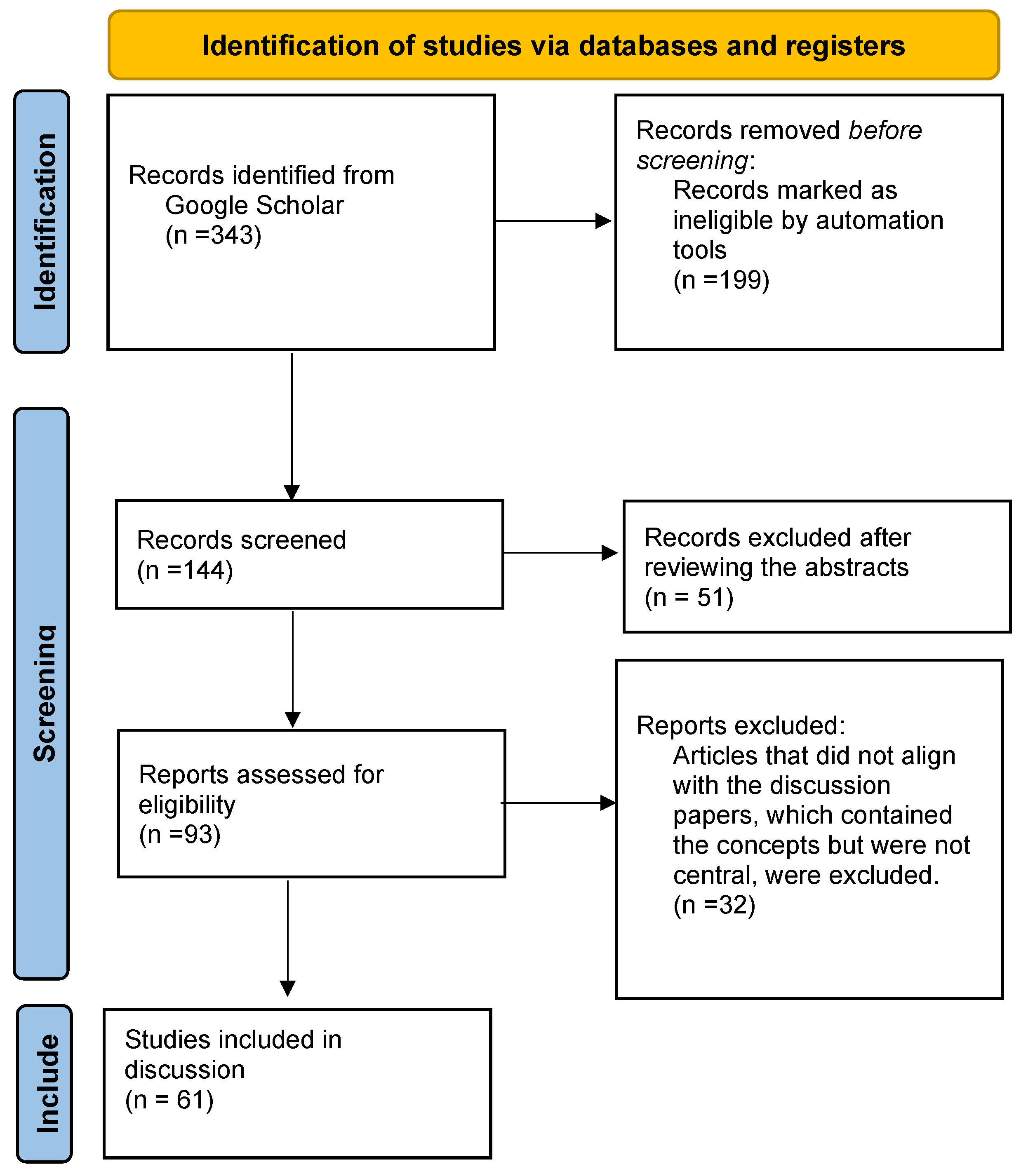

4. Methodology

- Identifying published studies on Knowledge Distillation in LLMs.

- Including studies that address Provenance Tracking in AI systems.

- Including studies that examine Semantic Integrity and its role in maintaining the trustworthiness of LLM outputs.

- The core search query combined the following criteria:

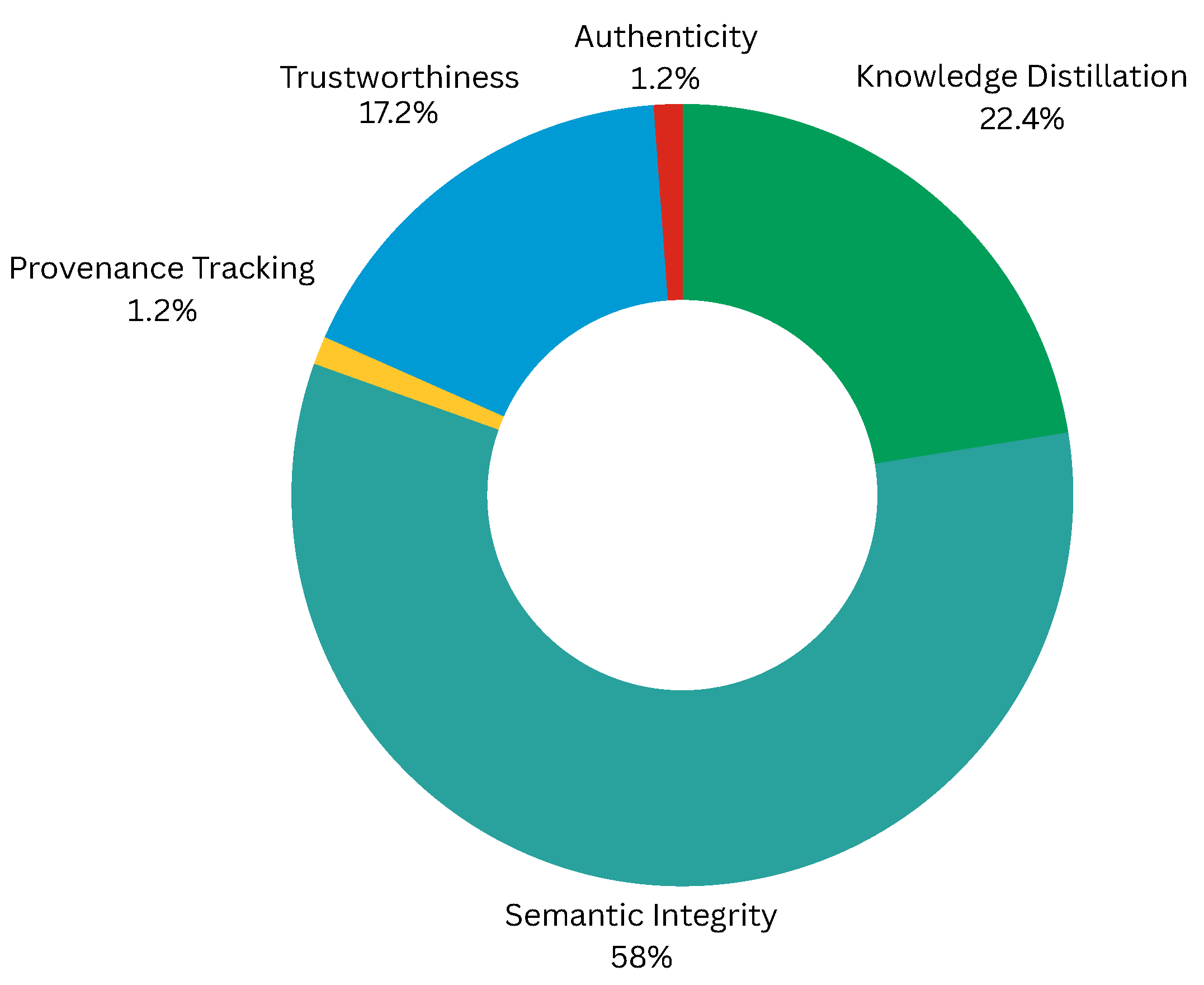

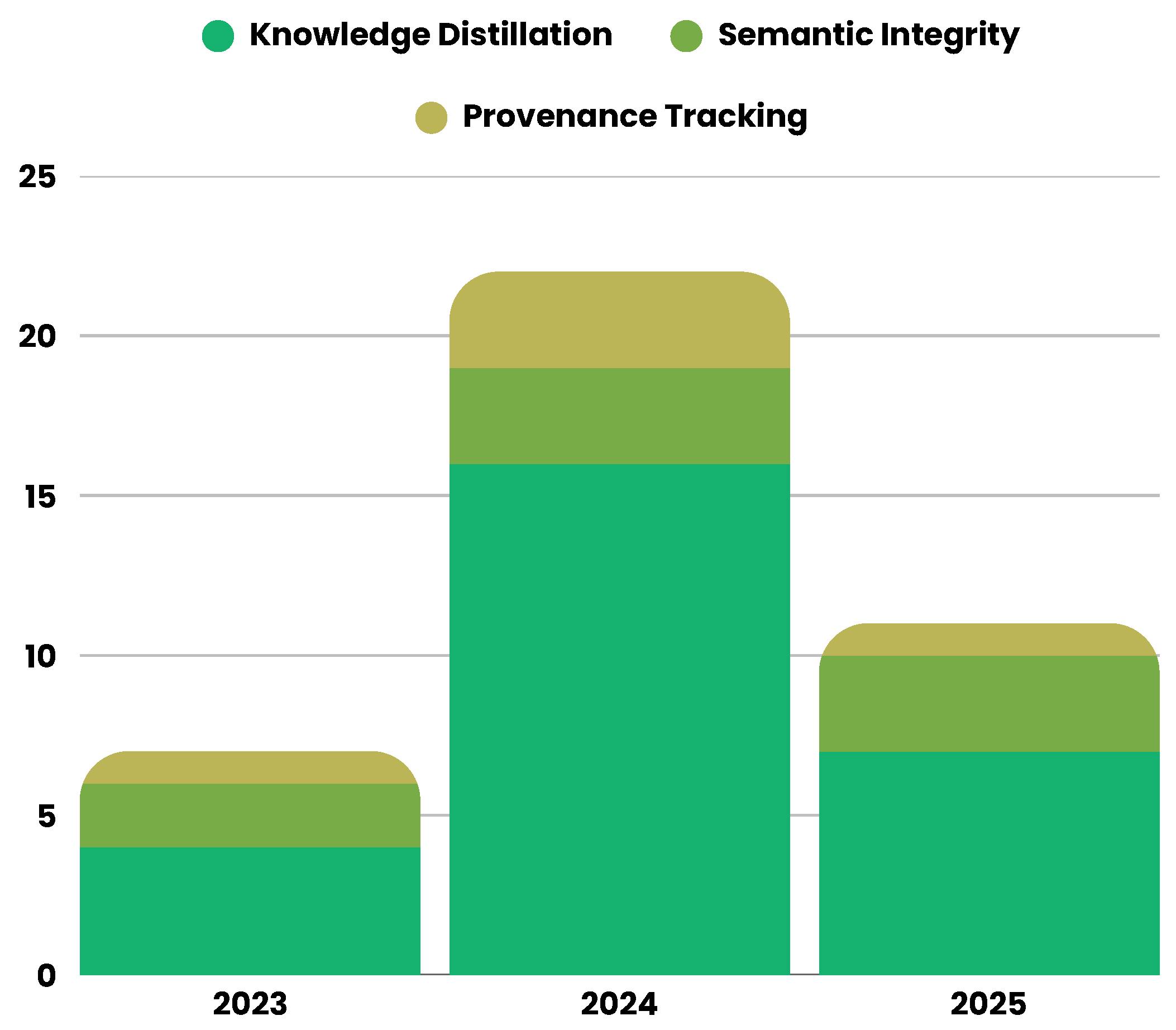

- Knowledge Distillation in LLMs: 77 papers

- Semantic Integrity in LLMs: 199 papers

- Provenance Tracking in LLMs: 4 papers

- Trustworthiness in LLMs: 59 papers

- Authenticity in LLMs: 4 papers

5. Key Findings of the Review

5.1. Knowledge Distillation

5.1.1. Teacher–Student Learning

- Confidential Distillation: Encrypting knowledge transfer to prevent unauthorized access [73]. The goal is to prevent unauthorized access to knowledge while still allowing a student model to learn from a teacher model.

5.1.2. Model Compression

- Quantization: Reducing parameter precision to enhance efficiency by reducing from 32-bit floats to 8-bit integers. Secure quantization prevents adversarial manipulation while maintaining predictive accuracy. In addition, TinyBERT and MicroBERT models have been enhanced successfully [77,78,79,80,81]. Accuracy is preserved by applying calibration and fine-tuning strategies during quantization-aware training.

5.1.3. Multi-Teacher Distillation

5.2. Semantic Integrity

5.2.1. Consistency Verification

5.2.2. Adversarial Robustness

5.2.3. Bias Detection and Mitigation

5.3. Provenance Tracking

Data Lineage Tracking

- Source Attribution: Identifying and recording the origins of both training and inference data to ensure verifiable and trustworthy knowledge generation [13]. Maintaining explicit records of data sources enables researchers and users to assess the reliability, credibility, and potential biases that influence model outputs.

- Data Versioning: Maintaining historical records of data modifications to track changes over time and prevent tampering. This ensures that model behavior and results can be accurately reproduced or audited.

- Dependency Tracking: Mapping data relationships and dependencies to prevent the propagation of errors or misinformation across multiple knowledge sources.

6. Conclusions and Future Research

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kulkarni, P.; Mahabaleshwarkar, A.; Kulkarni, M.; Sirsikar, N.; Gadgil, K. Conversational AI: An overview of methodologies, applications & future scope. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2019 5th International Conference on Computing, Communication, Control and Automation (ICCUBEA), Pune, India, 19–21 September 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Galley, M.; Li, L. Neural approaches to conversational AI. In Proceedings of the 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 8–12 July 2018; pp. 1371–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Manikandan, S.; Kishore, R. Ai-driven Text Generation: A Novel Gpt-based Approach for Automated Content Creation. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2024 2nd International Conference on Networking and Communications (ICNWC), Chennai, India, 2–4 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Duan, J.; Xu, K.; Cai, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y. A survey on large language model (llm) security and privacy: The good, the bad, and the ugly. High-Confid. Comput. 2024, 4, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Kong, K.; Liu, N.; Cui, L.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Kankanhalli, M. An llm can fool itself: A prompt-based adversarial attack. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.13345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.M.; Liu, Y. Condefects: A new dataset to address the data leakage concern for llm-based fault localization and program repair. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.16253. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Wei, L.; Cao, H.; Zhou, W.; Hu, S. Can large language models understand content and propagation for misinformation detection: An empirical study. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.12699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xhonneux, S.; Sordoni, A.; Günnemann, S.; Gidel, G.; Schwinn, L. Efficient adversarial training in llms with continuous attacks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 1502–1530. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Mo, F.; Wang, D.; Fu, Y.; Liu, K. LEKA: LLM-Enhanced Knowledge Augmentation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.17802. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, H.; Gao, S.; Sun, Q.; Li, J. Towards Objective Fine-tuning: How LLMs’ Prior Knowledge Causes Potential Poor Calibration? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.20903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zou, G.; Yang, S.; Lin, S.; Gan, Y.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y. Large language model meets graph neural network in knowledge distillation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 17295–17304. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, S.S.; Soremekun, E.; Chattopadhyay, S. Knowledge-based consistency testing of large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.12830. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Lu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Dai, Z.; Foo, C.S.; Ng, S.K.; Low, B.K.H. Source Attribution for Large Language Model-Generated Data. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.00646. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Li, M.; Tao, C.; Shen, T.; Cheng, R.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Tao, D.; Zhou, T. A survey on knowledge distillation of large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.13116. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Yoon, K.J. Knowledge distillation and student-teacher learning for visual intelligence: A review and new outlooks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 3048–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.; Chon, D. Trust & Safety of LLMs and LLMs in Trust & Safety. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.02113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. A survey on evaluation of large language models. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-training. OpenAI Technical Report. 2018. Available online: https://cdn.openai.com/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language_understanding_paper.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI Blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, G.; Mesnard, T.; Hardin, C.; Dadashi, R.; Bhupatiraju, S.; Pathak, S.; Sifre, L.; Rivière, M.; Kale, M.S.; Love, J.; et al. Gemma: Open models based on gemini research and technology. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.08295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, G.; Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Alayrac, J.B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; Dai, A.M.; Hauth, A.; Millican, K.; et al. Gemini: A family of highly capable multimodal models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, G.; Georgiev, P.; Lei, V.I.; Burnell, R.; Bai, L.; Gulati, A.; Tanzer, G.; Vincent, D.; Pan, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Gemini 1.5: Unlocking multimodal understanding across millions of tokens of context. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.05530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), (NAACL-HLT 2019), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, T.; Liu, Z.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, S.; Wu, Z.; Lyu, Y.; Shu, P.; Yu, X.; et al. Evaluation of openai o1: Opportunities and challenges of agi. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.18486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazi, Z.A.; Peng, W. Large language models in healthcare and medical domain: A review. Informatics 2024, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shool, S.; Adimi, S.; Saboori Amleshi, R.; Bitaraf, E.; Golpira, R.; Tara, M. A systematic review of large language model (LLM) evaluations in clinical medicine. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2025, 25, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Z.; Ma, J.; Zhang, X.; Hao, N.; Yan, A.; Nourbakhsh, A.; Yang, X.; McAuley, J.; Petzold, L.; Wang, W.Y. A survey on large language models for critical societal domains: Finance, healthcare, and law. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.01769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Wang, S.; Xie, J.; Zhu, T.; Yan, Y.; Ye, J.; Zhong, A.; Hu, X.; Liang, J.; Yu, P.S.; et al. Llm agents for education: Advances and applications. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.11733. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, C.; Li, Z.; Li, X. Information security based on llm approaches: A review. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.18215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Cummings, M.; Stimpson, A. Strengthening LLM trust boundaries: A survey of prompt injection attacks. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Human-Machine Systems (ICHMS), Toronto, ON, Canada, 15–17 May 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Zhu, W.; Jiao, P.; Gao, D.; Wu, O. Data poisoning in deep learning: A survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.22759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Qiu, Y.; Yu, H.; Yu, W.; Kong, J.; Chong, B.; Chen, B.; Wang, X.; Xia, S.T.; Xu, K. Privacy leakage on dnns: A survey of model inversion attacks and defenses. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.04013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leybzon, D.; Kervadec, C. Learning, forgetting, remembering: Insights from tracking llm memorization during training. In Proceedings of the 7th BlackboxNLP Workshop: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP, Miami, FL, USA, 15 November 2024; pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.Z.; Razniewski, S.; Kalo, J.C.; Singhania, S.; Chen, J.; Dietze, S.; Jabeen, H.; Omeliyanenko, J.; Zhang, W.; Lissandrini, M.; et al. Large language models and knowledge graphs: Opportunities and challenges. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.06374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Li, W.; Cai, M.; Saraipour, K.; Zhang, Z.; Lakkaraju, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S. How Post-Training Reshapes LLMs: A Mechanistic View on Knowledge, Truthfulness, Refusal, and Confidence. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.02904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Hou U, L.; Li, Z.; Guo, W. Large language model enhanced knowledge representation learning: A survey. Data Sci. Eng. 2025, 10, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mökander, J.; Schuett, J.; Kirk, H.R.; Floridi, L. Auditing large language models: A three-layered approach. AI Ethics 2024, 4, 1085–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldanda, A.K.; Zhang, S.X.; Das, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Rawls, S.; Sahu, S.; Naphade, M. Llm surgery: Efficient knowledge unlearning and editing in large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.13054. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, C.; Li, J. Knowledge editing for large language models: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Qi, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W. Knowledge conflicts for llms: A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.08319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Yu, B.; Maybank, S.J.; Tao, D. Knowledge distillation: A survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 1789–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Pei, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Chawla, N. Knowledge distillation on graphs: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 57, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, F.; Rhee, J.; Choe, Y.R. Knowledge Transfer from LLMs to Provenance Analysis: A Semantic-Augmented Method for APT Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.18316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Gao, C.; Yan, B.; Chen, Y. Survey on knowledge distillation for large language models: Methods, evaluation, and application. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Hasan, S.; Arafat, N.A.; Khan, A. Logical Consistency of Large Language Models in Fact-checking. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.16100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Yue, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhang, T.; Jiayang, C.; Yao, Y.; Gao, W.; Hu, X.; Qi, Z.; et al. Survey on factuality in large language models: Knowledge, retrieval and domain-specificity. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.07521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Stoll, A.; Lange, L.; Adel, H.; Schütze, H.; Strötgen, J. Bring Your Own Knowledge: A Survey of Methods for LLM Knowledge Expansion. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Xie, W.; Ng, S.K.; Chua, T.S. Knowledge Boundary of Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.12472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ruan, W.; Huang, W.; Jin, G.; Dong, Y.; Wu, C.; Bensalem, S.; Mu, R.; Qi, Y.; Zhao, X.; et al. A survey of safety and trustworthiness of large language models through the lens of verification and validation. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B. Procedures for Performing Systematic Reviews; Keele University: Keele, UK, 2004; Volume 33, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Woodcock, P.; Macura, B.; Collins, A. Making literature reviews more reliable through application of lessons from systematic reviews. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallett, R.; Hagen-Zanker, J.; Slater, R.; Duvendack, M. The benefits and challenges of using systematic reviews in international development research. J. Dev. Eff. 2012, 4, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirgaonkar, A.; Pandey, N.; Abay, N.C.; Aktas, T.; Aski, V. Knowledge Distillation Using Frontier Open-source LLMs: Generalizability and the Role of Synthetic Data. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.18588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nag, S.; Liu, H.; Tang, X.; Sarwar, S.M.; Cui, L.; Gu, H.; Wang, S.; He, Q.; Tang, J. Learning with Less: Knowledge Distillation from Large Language Models via Unlabeled Data. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Proceedings of the 2025 Annual Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL 2025), Albuquerque, NM, USA, 29 April–4 May 2025; Chiruzzo, L., Ritter, A., Wang, L., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 2627–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, X.; Liu, D.; Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, X. Teacher-student architecture for knowledge distillation: A survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.04268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Que, H.; Deng, K.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G.; Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; et al. Ddk: Distilling domain knowledge for efficient large language models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 98297–98319. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.; He, Z.; Gandre, S.A.; Pasupulety, U.; Shivakumar, S.K.; Lerman, K. Smoothing Out Hallucinations: Mitigating LLM Hallucination with Smoothed Knowledge Distillation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.11306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Dong, L.; Wei, F.; Huang, M. MiniLLM: Knowledge distillation of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.08543. [Google Scholar]

- Anshumann, A.; Zaidi, M.A.; Kedia, A.; Ahn, J.; Kwon, T.; Lee, K.; Lee, H.; Lee, J. Sparse Logit Sampling: Accelerating Knowledge Distillation in LLMs. In Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Vienna, Austria, 27 July–1 August 2025; pp. 18085–18108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, S.; Gao, F.; Zhuang, Y.; Tang, S.; Liu, Q.; Xu, M. Logic Distillation: Learning from Code Function by Function for Planning and Decision-making. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.19405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tian, B.; Yu, F.; He, Y. An Anomaly Detection Model Training Method Based on LLM Knowledge Distillation. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2024 International Conference on Networking and Network Applications (NaNA), Yinchuan City, China, 9–12 August 2024; pp. 472–477. [Google Scholar]

- Di Palo, F.; Singhi, P.; Fadlallah, B. Performance-Guided LLM Knowledge Distillation for Efficient Text Classification at Scale. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.05045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Bang, J.; Kwon, S.; Kim, T. Multi-aspect Knowledge Distillation with Large Language Model. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.13341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Tao, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, R.; Zhao, Z.; Wong, N. Rethinking kullback-leibler divergence in knowledge distillation for large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.02657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Z.; Yang, Y.; Huang, M.; Li, D. LLM-based privacy data augmentation guided by knowledge distillation with a distribution tutor for medical text classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.16515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gou, J.; Yu, B.; Du, L.; Tao, Z.Y.D. Federated distillation: A survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.08564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Zhu, T.; Zhou, W.; Yu, P.S. Knowledge distillation in federated learning: A survey on long lasting challenges and new solutions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangpu, Q.; Gao, H. Efficient Model Compression and Knowledge Distillation on Llama 2: Achieving High Performance with Reduced Computational Cost. 2024. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/osf/hax36 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Du, D.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, S.; Guo, J.; Cao, T.; Chu, X.; Xu, N. Bitdistiller: Unleashing the potential of sub-4-bit llms via self-distillation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.10631. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, A.; Stock, P.; Graham, B.; Grave, E.; Gribonval, R.; Jegou, H.; Joulin, A. Training with quantization noise for extreme model compression. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.07320. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Oguz, B.; Zhao, C.; Chang, E.; Stock, P.; Mehdad, Y.; Shi, Y.; Krishnamoorthi, R.; Chandra, V. Llm-qat: Data-free quantization aware training for large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.17888. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, E.; Fang, L.; Ma, P.; Zhai, X. Knowledge distillation of LLM for automatic scoring of science education assessments. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.15842. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pang, P.C.I. MicroBERT: Distilling MoE-Based Knowledge from BERT into a Lighter Model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivas, S.T.; Muralidharan, S.; Joshi, R.; Chochowski, M.; Mahabaleshwarkar, A.S.; Shen, G.; Zeng, J.; Chen, Z.; Suhara, Y.; Diao, S.; et al. Llm pruning and distillation in practice: The minitron approach. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.11796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, S.; Turuvekere Sreenivas, S.; Joshi, R.; Chochowski, M.; Patwary, M.; Shoeybi, M.; Catanzaro, B.; Kautz, J.; Molchanov, P. Compact language models via pruning and knowledge distillation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 41076–41102. [Google Scholar]

- Mansourian, A.M.; Ahmadi, R.; Ghafouri, M.; Babaei, A.M.; Golezani, E.B.; Ghamchi, Z.Y.; Ramezanian, V.; Taherian, A.; Dinashi, K.; Miri, A.; et al. A Comprehensive Survey on Knowledge Distillation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.12067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, G.; Huang, J.X. MTMS: Multi-teacher Multi-stage Knowledge Distillation for Reasoning-Based Machine Reading Comprehension. In Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 1995–2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Han, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, W.; Chawla, N.V. Beyond Answers: Transferring Reasoning Capabilities to Smaller LLMs Using Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.04616. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Xu, P.; Chang, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, L.; Chen, X. When object detection meets knowledge distillation: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 10555–10579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shi, L. DistillSeq: A Framework for Safety Alignment Testing in Large Language Models Using Knowledge Distillation. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, Vienna, Austria, 16–20 September 2024; pp. 578–589. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Wang, Y.; Ye, J.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, P.; Xu, K. Semantic Importance-Aware Communications with Semantic Correction Using Large Language Models. IEEE Trans. Mach. Learn. Commun. Netw. 2025, 3, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.W.; Chan, J.; Fu, M.; Kim, N.; Mehta, A.; Raghavan, D.; Cetintemel, U. Semantic Integrity Constraints: Declarative Guardrails for AI-Augmented Data Processing Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.00600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, H.; Gupta, V.; Rosati, D.; Majumdar, S. Semantic consistency for assuring reliability of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.09138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galitsky, B.; Chernyavskiy, A.; Ilvovsky, D. Truth-o-meter: Handling multiple inconsistent sources repairing LLM hallucinations. In Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 2817–2821. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, A.; Richardson, S.; Schneider, J.; Cummings, A.; Forsberg, N.; Klein, J. Semantic drift mitigation in large language model knowledge retention using the residual knowledge stability concept. TechRxiv Preprint 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Sun, H.; Xue, N. Fact-checking AI-generated news reports: Can LLMs catch their own lies? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.18293. [Google Scholar]

- Chanenson, J.; Pickering, M.; Apthorpe, N. Automating governing knowledge commons and contextual integrity (GKC-CI) privacy policy annotations with large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.02192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Ye, W.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, N.; et al. Promptrobust: Towards evaluating the robustness of large language models on adversarial prompts. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM Workshop on Large AI Systems and Models with Privacy and Safety Analysis, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 14–18 October 2023; pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Ruan, S.; Su, H.; Yin, Z. Exploring the robustness of decision-level through adversarial attacks on llm-based embodied models. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 8120–8128. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, M. Adversarial attacks on large language models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Science, Engineering and Management, Birmingham, UK, 16–18 August 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Su, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X. Sanitizing Large Language Models in Bug Detection with Data-Flow. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 3790–3805. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Singh, N.; Vatsal, S. Robustness of llms to perturbations in text. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.08989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Zhang, J.M.; Bu, Q.; Xie, X.; Chen, J.; Cui, H. Bias testing and mitigation in llm-based code generation. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2025, 34, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Chen, K.; Li, M.; Feng, P.; Bi, Z.; Liu, J.; Niu, Q. Securing large language models: Addressing bias, misinformation, and prompt attacks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.08087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, J.E. Explainable AI for Large Language Models via Context-Aware Word Embeddings. In Proceedings of the 2025 AIAA Science and Technology Forum and Exposition (AIAA SCITECH Forum), Orlando, FL, USA, 6–10 January 2025; p. 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Mumuni, F.; Mumuni, A. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI): From inherent explainability to large language models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.09967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, S.; Treutlein, J.; Bricken, T.; Lindsey, J.; Marcus, J.; Mishra-Sharma, S.; Ziegler, D.; Ameisen, E.; Batson, J.; Belonax, T.; et al. Auditing language models for hidden objectives. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.10965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Vorster, L. LLM Supply Chain Provenance: A Blockchain-Based Approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on AI Research, Lisbon, Portugal, 5–6 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Knowledge Management (KM) | Information Security (IS) |

|---|---|---|

| Truthfulness | Fact-checking accuracy, consistency, source reliability | Source reliability |

| Robustness | Adversarial robustness, out-of-distribution robustness | – |

| Safety | Toxicity, bias and discrimination, misinformation | – |

| Fairness | Group fairness, individual fairness, counterfactual fairness | – |

| Privacy | – | Data privacy, membership inference, attribute inference |

| Reference | Title | Highlight | Comparison with Our Work |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [53] | Bring Your Own Knowledge: A Survey of Methods for LLM Knowledge Expansion | Reviews methods for enhancing LLMs with diverse knowledge, including continual learning and retrieval-based adaptation. | Our work extends integrity preservation by incorporating provenance and distillation within secure contexts. |

| Li et al. [54] | Knowledge Boundary of Large Language Models: A Survey | Explores LLM knowledge boundaries, categorizes knowledge types, and review methods to identify and address limitations in knowledge retention and accuracy. | Our work investigates the interplay between security, knowledge distillation, and provenance mechanisms to offer a comprehensive perspective on LLM output integrity. |

| Wang et al. [42] | Large Language Model Enhanced Knowledge Representation Learning: A Survey | Highlights how LLMs enhance Knowledge Representation Learning (KRL). | Our work shifts the focus by including distillation, provenance, and security to address integrity beyond KRL. |

| Yang et al. [50] | Survey on Knowledge Distillation for Large Language Models: Methods, Evaluation, and Application | Surveys knowledge distillation for LLMs, categorizing techniques into white-box and black-box KD. | Our work connects knowledge distillation and semantic integrity to provenance and security for robust LLM integrity. |

| Huang et al. [55] | A survey of safety and trustworthiness of large language models through the lens of verification and validation | Reviews safety and trustworthiness of LLMs, categorising vulnerabilities and examining traditional verification and validation techniques. | Our work integrates safety and trustworthiness with provenance, distillation, and semantic integrity to strengthen LLM robustness. |

| Xu et al. [14] | A survey on knowledge distillation of large language models | Provides a comprehensive analysis of knowledge distillation for LLMs. | Our work extends knowledge distillation by emphasizing its role in integrity and provenance within LLMs. |

| Criteria | Value |

|---|---|

| Source | Google Scholar |

| Type | Journal, Conference, Book Chapters |

| Search Field | Title |

| Sort Order | Relevance |

| Year Range | 2023–2025 |

| Paper | KD Type | Strengths | Weaknesses/Limitations | Applications/Implementation | Data/Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General/Survey KD | |||||

| [47] | Survey | Comprehensive overview of KD techniques | General survey; lacks experiments | Theoretical understanding | N/A |

| [87] | Object Detection KD Survey | Focused on object detection; highlights challenges | Limited to OD; not NLP-generalizable | Object detection | Detection datasets |

| [48] | Graph KD Survey | Handles structured graph data | Less explored for LLMs | Graph-based learning | Graph datasets |

| [74] | Federated KD Survey | Overview of federated KD methods | Survey only; no experiments | Distributed learning/federated learning | Federated datasets |

| [75] | Federated KD Survey | Highlights challenges and solutions | Mostly conceptual | Federated learning/NLP | Distributed nodes/data |

| Teacher–Student/LLM → Student | |||||

| [63] | Teacher–Student | Covers various architectures; adaptable | Mostly survey; minimal implementation | Model compression, NLP | GPU-heavy if teacher is large |

| [61] | Teacher–Student/LLM | Uses synthetic data; generalizable | Quality of synthetic data can affect student | NLP tasks; LLM distillation | Open-source LLM + synthetic data |

| [62] | LLM → Student via unlabeled data | Adaptive sample selection (LLKD); efficient | Depends on teacher confidence; complex selection | Text classification; NLP | LLM inference + student training |

| [64] | Domain Knowledge KD | Efficiently distills domain-specific knowledge | Limited to domain knowledge; scalability | Domain-specific NLP/LLM compression | Teacher + domain dataset |

| Teacher-Student/LLM → Student | |||||

| [65] | Smoothed KD | Reduces hallucinations in LLMs | Adds computational overhead | LLM hallucination mitigation | Teacher + student LLMs |

| [66] | LLM → Smaller LLM | Compresses LLMs effectively | May lose reasoning capability | Lightweight LLM deployment | Teacher LLM required |

| [68] | Logic Distillation | Function-by-function code distillation; task-specific | Limited to code/planning tasks | Planning, decision-making | Teacher LLM + code dataset |

| [69] | LLM → Student/Anomaly | Focused on anomaly detection | Specific to network anomalies | Anomaly detection models | LLM + anomaly dataset |

| [70] | LLM → Student/Text Classification | Performance-guided; scalable | Requires teacher inference | Text classification at scale | Teacher LLM + text datasets |

| [71] | Multi-aspect KD | Captures multiple aspects of teacher knowledge | Complexity in combining aspects | NLP; LLM reasoning | Teacher LLM + student model |

| [72] | KD Metrics/LLM | Rethinks KL divergence for LLM distillation | Only focuses on loss; needs experiments | LLM training/evaluation | Teacher + student LLM |

| [73] | Privacy-aware KD | Guides student with distribution tutor; protects privacy | Limited to medical text; complex tutor mechanism | Medical text classification | LLM + privacy dataset |

| [80] | LLM → Student/Assessment | Auto-scoring science assessments | Limited to education domain | Educational assessment scoring | Teacher LLM + student data |

| [81] | MoE → Lighter Model | Distills Mixture-of-Experts BERT to small model | MoE-specific; task limited | Lightweight NLP models | Teacher MoE BERT |

| [49] | LLM → Security | Semantic-augmented knowledge transfer for APT detection | Limited to provenance analysis; needs LLM teacher | Cybersecurity; APT detection | LLM + network logs |

| [61] | Teacher–Student LLM | Uses open-source LLMs; evaluates generalizability | Synthetic data quality critical | NLP model compression | LLM + synthetic data |

| [62] | LLM → Student | Efficient with unlabeled data | Pseudo-label noise | NLP | Teacher LLM + unlabeled dataset |

| Model Compression/Quantization/Pruning | |||||

| [76] | LLaMA2 Compression | High performance; low computation cost | Focused on LLaMA2 only | Model compression | GPU + quantization |

| [11] | GNN + LLM KD | Combines graph info | Limited to graph-based tasks | NLP + graph tasks | LLM + GNN data |

| [77] | Self-distillation/Sub-4-bit LLM | Very low-bit models; efficient | May degrade performance if too low-bit | LLM compression | GPU + quantized LLM |

| Model Compression/Quantization/Pruning | |||||

| [78] | Quantization + KD | Extreme model compression | Only tested on small models | Model compression | Quantization noise training |

| [79] | Data-free QAT KD | Quantization aware training for LLM | Data-free assumptions may limit generality | LLM compression | Teacher + student LLM |

| [83] | Pruning + KD | Compact LMs; pruning + distillation | Needs careful pruning schedule | Efficient LLM deployment | Teacher + pruning framework |

| [82] | Pruning + KD (Minitron) | Practical LLM distillation workflow | Implementation heavy | LLM pruning | Teacher LLM + GPU |

| Multi-Teacher/Multi-Stage | |||||

| [85] | Multi-teacher Multi-stage | Combines multiple teachers; reasoning-focused | High computation; complex alignment | MRC (Machine Reading Comprehension) | Multiple teacher models |

| [86] | Multi-Teacher/ Reasoning | Transfers reasoning capabilities; multi-teacher | Computationally expensive | Small LLM reasoning improvement | Teacher LLMs |

| [84] | Survey/ Comprehensive | Covers most KD methods; up-to-date | No experiments; mainly conceptual | Reference for KD research | N/A |

| Papers | Focus/Domain | Method/Approach | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency Verification | |||

| [88] | Safety Alignment | Knowledge Distillation framework for testing LLMs | Evaluating LLM safety and alignment |

| [89] | Semantic Communications | Importance-aware semantic correction using LLMs | Reliable communication |

| [51] | Logical Consistency | Consistency verification of LLM outputs | Fact-checking and verification |

| [90] | Semantic Integrity Constraints | Declarative guardrails for AI-augmented data processing | Ensuring reliable data transformations |

| [92] | Inconsistent Sources | Multi-source repair to mitigate hallucinations | Improving factual correctness of LLM outputs |

| [93] | Semantic Drift | Residual knowledge stability concept | Maintaining knowledge retention in LLMs |

| [91] | Semantic Consistency | Monitoring and enforcing consistency constraints | Reliable LLM outputs |

| [94] | Fact-Checking | LLM self-evaluation for detecting misinformation | Automated detection of AI-generated false reports |

| [95] | Contextual Integrity/Privacy | Automating privacy policy annotations using LLMs | Governance and compliance |

| Adversarial Robustness | |||

| [96] | Adversarial Prompts | Evaluation of LLMs under adversarial prompts | Measuring LLM robustness |

| [97] | Adversarial Attacks | Decision-level robustness analysis | Assessing vulnerability of embodied LLMs |

| [98] | Adversarial Attacks | Attack strategies on LLMs | Understanding LLM weaknesses |

| [99] | Bug Detection | Data-flow sanitization with LLMs | Improving reliability of code-generation LLMs |

| [100] | Text Perturbations | Robustness testing | Ensuring stability of LLM outputs |

| Bias Detection and Mitigation | |||

| [101] | Bias in Code Generation | Bias testing and mitigation in LLMs | Reducing unwanted bias in outputs |

| [102] | Bias | Addressing bias, misinformation, prompt attacks | Secure LLM deployment |

| Technique | Sub-Techniques | Purpose | Integrity Aspect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Distillation | Teacher-Student | Preserves knowledge from teacher to student | Knowledge Management |

| Model Compression | Reduces complexity, preserves knowledge | Knowledge Management | |

| Multi-Teacher | Integrates insights from multiple teachers for robustness | Knowledge Management | |

| Semantic Integrity | Consistency Verification | Ensures outputs are logically coherent | Knowledge Management |

| Adversarial Robustness | Protects model from manipulated inputs | Information Security | |

| Bias Mitigation | Reduces social, cultural, demographic biases | Knowledge Management and Information Security | |

| Provenance Tracking | Data Lineage | Maintains traceable records of data usage | Information Security |

| Source Attribution | Identifies origin of data and outputs | Information Security and Knowledge Management |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abishethvarman, V.; Sabrina, F.; Kwan, P. Knowledge Integrity in Large Language Models: A State-of-The-Art Review. Information 2025, 16, 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121076

Abishethvarman V, Sabrina F, Kwan P. Knowledge Integrity in Large Language Models: A State-of-The-Art Review. Information. 2025; 16(12):1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121076

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbishethvarman, Vadivel, Fariza Sabrina, and Paul Kwan. 2025. "Knowledge Integrity in Large Language Models: A State-of-The-Art Review" Information 16, no. 12: 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121076

APA StyleAbishethvarman, V., Sabrina, F., & Kwan, P. (2025). Knowledge Integrity in Large Language Models: A State-of-The-Art Review. Information, 16(12), 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121076