Mapping Theoretical Perspectives for Requisite Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Defining Requisite Resilience as a Capability Within Complex Adaptive Systems

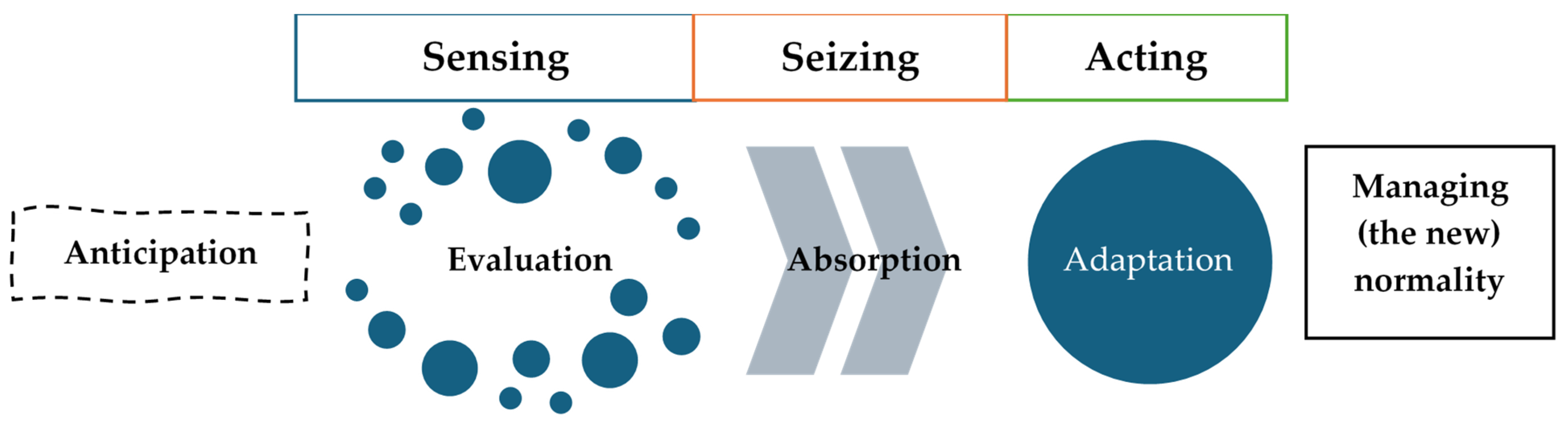

2.1. Requisite Resilience

2.2. Complex Adaptive Systems

2.3. Interorganizational Interactions as a Source of Resilience

3. Methodological Approach

3.1. Identification and Categorisation

3.2. Evaluation Grid and Operational Definitions

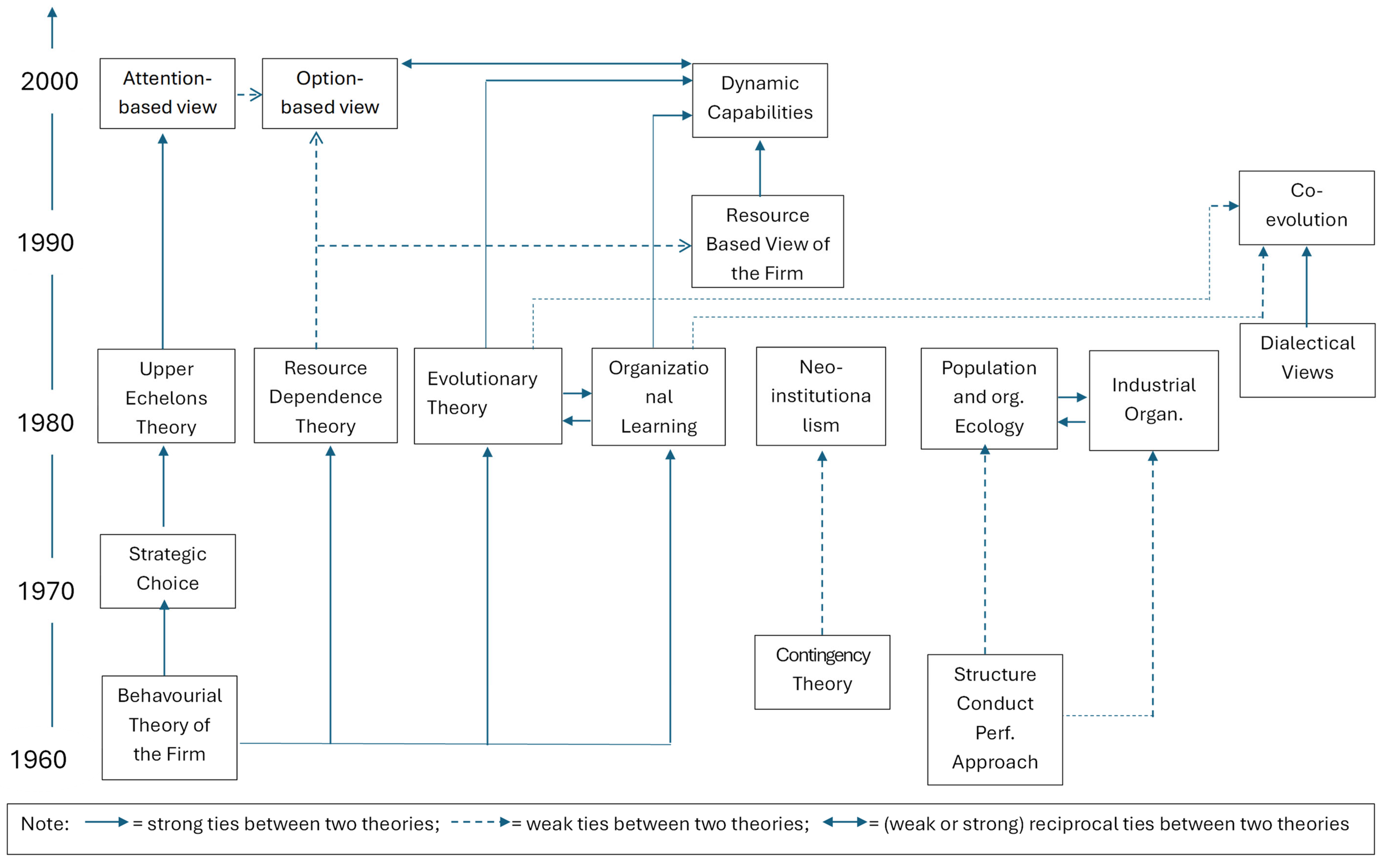

4. Main Theories

4.1. Foundational or Diagnostic Theories

4.1.1. Organizational Ecology

4.1.2. Contingency Theory and Neo-Institutionalism

4.2. Enabling or Capability-Building Theories

4.2.1. Strategic Choice and Upper Echelons Theory

4.2.2. Resource Dependence Theory

4.2.3. Resources, Dynamic Capabilities and Knowledge

4.2.4. Dialectical and Co-Evolutionary Perspectives

4.2.5. Attention-Based View

4.3. From Passive to Active Requisite Resilience

5. Analysis of Theories of the Firm for Requisite Resilience

5.1. Mapping

5.2. Discussion: Evaluation of Theoretical Contributions to Requisite Resilience

5.2.1. Foundational Perspectives as Contextual Baselines

5.2.2. Enabling Perspectives as Drivers of Adaptive Agency

5.2.3. Capability-Based Perspectives as Enablers of Sustained Adaptability

5.2.4. Oriented Perspectives as Integrators of Constraint and Agency

5.2.5. Cognitive Perspectives as Triggers for Timely Adaptation

5.3. Integrating Perspectives for Requisite Resilience

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elkington, R. Leadership Decision-Making Leveraging Big Data in Vuca Contexts. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2018, 12, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghemawat, P. The New Global Road Map: Enduring Strategies for Turbulent Times; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management: Organizing for Innovation and Growth; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; ISBN 0-19-954512-X. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, E.; Neukam, M.; Martins-Nourry, L.; Gnamm, M.-B.; Djuricic, K.; Raffin, D.; Burger-Helmchen, T. Requisite Resilience: Towards a Definition; evoREG Research Note #50; Fraunhofer ISI: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Boisot, M.; McKelvey, B. Complexity and Organization-Environment Relations: Revisiting Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety. In The SAGE Handbook of Complexity and Management; Allen, P., Maguire, S., McKelvey, B., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Levinthal, D.A.; Marino, A. Three Facets of Organizational Adaptation: Selection, Variety, and Plasticity. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Wise Company: How Companies Create Continuous Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, E.; Bellaj, A.; Bischoff, L.; Djuricic, K.; Jülicher, M.; Gnamm, M.-B.; Martins-Nourry, L.; Raffin, D.; Muller, E. Deep Resilience: Towards a Working Definition; evoREG Research Notes #48; Fraunhofer ISI: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Duchek, S. Organizational Resilience: A Capability-Based Conceptualization. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnard, K.; Bhamra, R. Organisational Resilience: Development of a Conceptual Framework for Organisational Responses. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5581–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhaime, I.M.; Hitt, M.A.; Lyles, M.A. Strategic Management: State of the Field and Its Future; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-0-19-009089-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, W.R. An Introduction to Cybernetics; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1956; ISBN 978-1-61427-765-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, M.; Stanske, S.; Lieberman, M. Strategic Responses to Crisis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, O16–O27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidanboy, M. Organizations and Complex Adaptative Systems; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gkatzoglou, F.; Sofianos, E.; Barbier-Gauchard, A. The EU Public Debt Synchronization: A Complex Networks Approach. Economies 2025, 13, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heraud, J.-A.; Kerr, F.; Burger-Helmchen, T. Creative Management of Complex Systems; Wiley-ISTE: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-84821-957-1. [Google Scholar]

- George, G.; Lin, Y. Analytics, Innovation, and Organizational Adaptation. Innovation 2017, 19, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D. Organizational Learning: Theory, Method and Practice, 2nd ed.; Financial Times/Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, R.D. Complexity and Creativity in Organizations; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P. Complexity Theory and Organization Science. Organ. Sci. 1999, 10, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnard, K.; Bhamra, R.; Tsinopoulos, C. Building Organizational Resilience: Four Configurations. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2018, 65, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottam, R.; Ranson, W.; Vounckx, R. Chaos and Chaos; Complexity and Hierarchy. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2015, 32, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, B.; Ramanujam, R. Through the Looking Glass of Complexity: The Dynamics of Organizations as Adaptive and Evolving Systems. Organ. Sci. 1999, 10, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.; Bhatia, M. Organizational Complexity and Computation. In The Blackwell Companion to Organizations; Baum, J.A.C., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 442–466. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Sull, D.N. Strategy as Simple Rules. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2001, 79, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, I.P. Technology Management—A Complex Adaptive Systems Approach. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2003, 25, 728–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohendet, P.; Llerena, P. Routines and Incentives: The Role of Communities in the Firm. Ind. Corp. Change 2003, 12, 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, S. Brain of the Firm; Chichester Eng. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1981; ISBN 978-0-471-27687-6. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. Decision and Control; Chichester, John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-471-94838-4. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, S. Diagnosing the System for Organizations; Chichester West Sussex; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-471-90675-9. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, W.L.; Lee, M.; Lim, W.-S. The Relational Activation of Resilience Model: How Leadership Activates Resilience in an Organizational Crisis. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2017, 25, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behfar, S.K.; Turkina, E.; Burger-Helmchen, T. Knowledge Management in OSS Communities: Relationship between Dense and Sparse Network Structures. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 38, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luedicke, M.K.; Husemann, K.C.; Furnari, S.; Ladstaetter, F. Radically Open Strategizing: How the Premium Cola Collective Takes Open Strategy to the Extreme. Long Range Plann. 2017, 50, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbook on the Economics and Theory of the Firm; Dietrich, M., Krafft, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-78195-611-3. [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom, P.; Roberts, J. Economic Theories of the Firm: Past, Present, and Future. Can. J. Econ. 1988, 21, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H.; Lampel, J.; Ahlstrand, B. Strategy Safari: A Guided Tour Through The Wilds of Strategic Management; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 0-7432-7057-6. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, I.T.; Cooper, C.L.; Sarkar, M.; Curran, T. Resilience Training in the Workplace from 2003 to 2014: A Systematic Review. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 533–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raetze, S.; Duchek, S.; Maynard, M.T.; Kirkman, B.L. Resilience in Organizations: An Integrative Multilevel Review and Editorial Introduction. Group Organ. Manag. 2021, 46, 607–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton, A.M. The Six Dimensions of Strong Theory. Organ. Sci. 2025, 36, 1242–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, G.R. Organizational Ecology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1984, 10, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.; Freeman, J. The Population Ecology of Oganizations. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 82, 50–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger-Helmchen, T.; Hussler, C.; Cohendet, P. Les Grands Auteurs en Management de L’innovation et de la Créativité, 1st ed.; Editions EMS: Paris, France, 2016; ISBN 978-2-84769-812-1. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, H. Organizations Evolving, 1st ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1999; ISBN 0-8039-8918-0. [Google Scholar]

- Boutillier, S.; Laperche, B. II. Christopher Freeman. La systémique de l’innovation. In Les Grands Auteurs en Management de L’innovation et de la Créativité; EMS Éditions: Caen, France, 2023; pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Magretta, J. Understanding Michael Porter: The Essential Guide to Competitition and Strategy; Harvard Business Review Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, T.; Stalker, G.M. The Management of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1961; ISBN 978-0-19-828878-7. [Google Scholar]

- Burger-Helmchen, T.; Hussler, C.; Muller, P. Management; Vuibert: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, P.R.; Lorsch, J.W. Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 1976; ISBN 978-0-87584-064-2. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathe, K.; Witt, U. The Nature of the Firm—Static versus Developmental Interpretations. J. Manag. Gov. 2001, 5, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohendet, P.; Dupouët, O.; Llerena, P.; Naggar, R.; Rampa, R. Knowledge-Based Approaches to the Firm: An Idea-Driven Perspective. Ind. Corp. Change 2025, 34, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatecola, G.; Cristofaro, M. Hambrick and Mason’s “Upper Echelons Theory”: Evolution and Open Avenues. J. Manag. Hist. 2018, 26, 116–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, P.J.H. Scenario Planning: A Tool for Strategic Thinking. Sloan Manage. Rev. 1995, 36, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Popli, M.; Ahsan, F.M.; Mukherjee, D. Upper Echelons and Firm Internationalization: A Critical Review and Future Directions. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Hambrick, D.C. It’s All about Me: Narcissistic Chief Executive Officers and Their Effects on Company Strategy and Performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 351–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Models of Bounded Rationality, New ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982; ISBN 978-0-262-69086-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1978; ISBN 978-0-8047-4789-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gandia, R.; Gardet, E. Sources of Dependence and Strategies to Innovate: Evidence from Video Game SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 1136–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger-Helmchen, T. The Dynamics between Plural and Network-Based Entrepreneurship in Small High-Tech Firms. In Innovation Networks and Clusters: The Knowledge Backbone; Laperche, B., Uzunidis, D., Sommers, P., Eds.; Peter Lang: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gandia, R.; Brion, S. How to Avoid Dependence in the Videogame Industry: The Case of Ankama. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2016, 18, 26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1959; ISBN 0-19-828977-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerfelt, B. A Resource-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hamel, G. The Core Competence of the Corporation. Harvard Business Review, May–June 1990; 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Wright, M.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr. The Resource-Based View of the Firm: Ten Years after 1991. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, K.R.; Prahalad, C.K. A Resource-Based Theory of the Firm: Knowledge versus Opportunism. Organ. Sci. 1996, 7, 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussler, C.; Burger-Helmchen, T. La connaissance: L’atome de la stratégie. In Les Grands Courants en Management Stratégique; Liarte, S., Ed.; EMS GEODIF: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 195–220. ISBN 978-2-37687-317-4. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D.E.; Mousavi, R. A Knowledge Management Perspective of Generative Artificial Intelligence. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2024, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Burger-Helmchen, T. Evolving Knowledge Management: Artificial Intelligence and the Dynamics of Social Interactions. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felin, T.; Foss, N.J.; Ployhart, R.E. The Microfoundations Movement in Strategy and Organization Theory. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2015, 9, 575–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Furr, N.R.; Bingham, C.B. Microfoundations of Performance: Balancing Efficiency and Flexibility in Dynamic Environments. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Enacted Sensemaking in Crisis Situations. J. Manag. Stud. 1988, 25, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 0-7879-9649-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois, L.J. On the Measurement of Organizational Slack. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1981, 6, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger-Helmchen, T. Creation and Co-Evolution of Strategic Options by Firms: An Entrepreneurial and Managerial Approach of Flexibility and Resource Allocation. In Powerful Finance and Innovation Trends in a High-Risk Economy; Laperche, B., Uzunidis, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2008; pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Brahm, F.; Poblete, J. Organizational Culture, Adaptation, and Performance. Organ. Sci. 2024, 35, 1823–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, W.P.; Burgelman, R.A. Evolutionary Perspectives on Strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.R.; Dosi, G.; Helfat, C.E.; Pyka, A.; Saviotti, P.P.; Lee, K.; Dopfer, K.; Malerba, F.; Winter, S.G. Modern Evolutionary Economics: An Overview; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-108-44619-8. [Google Scholar]

- Borsato, A.; Lorentz, A. Data Production and the Coevolving AI Trajectories: An Attempted Evolutionary Model. J. Evol. Econ. 2023, 33, 1427–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W. Towards an Attention-Based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, W.; Joseph, J. An Attention-Based Theory of Strategy Formulation: Linking Micro and Macro Perspectives in Strategy Processes. Adv. Strateg. Manag. 2005, 22, 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Mcmullen, J.S.; Ocasio, W. Is That an Opportunity? An Attention Model of Top Managers’ Opportunity Beliefs for Strategic Action. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 626–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigeorgis, L.; Reuer, J.J. Real Options Theory in Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaraonye, I.; Titus, V., Jr.; Cavanaugh, J. A Real Options Perspective on Entrepreneurial Orientation and Government Ties. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2025, 49, 817–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Williams, D.W.; Hunt, R.A. A Real Options Reasoning Perspective on Entrepreneurs’ Decision-Making Over Time. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2025, 10422587251371133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatecola, G. Organizational Adaptation: An Update. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2012, 20, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukam, M.; Bollinger, S. Encouraging Creative Teams to Integrate a Sustainable Approach to Technology. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 150, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element of Analysis | Example 1 (Cluster) | Example 2 (Ecosystem) | Example 3 (Crisis Coalition) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Exchange | Technical know-how, informal updates | Market intelligence, coordination data | Alerts, emergency procedures |

| Participants | Middle managers, engineers | Executives, business unit heads | Cross-level teams, crisis response units, all willing agents |

| Structure of Exchange | Informal, frequent, peer-to-peer | Structured meetings, digital platforms | Ad hoc, protocol-driven |

| Nature of Relationship | Cooperative, trust-based | Co-opetitive, strategic alliances | Temporary coordination |

| Pre-crisis Embeddedness | High, long-standing community ties | Moderate, strategic interdependence | Low, assembled during crisis |

| Impact on Requisite Resilience | Facilitates fast, decentralized response through shared norms and trust | Enables coordinated strategic repositioning with adaptive room for maneuver | Effectiveness depends rapid mobilization capacity |

| Theory | View of the Environment | Main Mechanism of Adaptation | Role of Managerial Agency | Implications for Requisite Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Ecology | Deterministic, environment selects survivors | Variation–selection–retention at population level | Minimal | Focus on passive RR: survival depends on structural fit; little capacity for strategic adaptation |

| Industrial Organization | Largely deterministic but allows strategic positioning | Competition driven by industry structure | Limited | Highlights external constraints but introduces strategic levers; RR depends on positioning within competitive dynamics |

| Contingency Theory | Adaptive, fit-driven | Structural alignment with environmental demands | Moderate | Supports RR when structures match environmental dynamism; emphasizes configurational adaptability |

| Neo-institutionalism | Deterministic through institutional norms | Isomorphism via legitimacy-seeking behaviours | Minimal | Ensures stability but risks rigidity; promotes RR in stable contexts but limits transformative capacity |

| Upper Echelons Theory | Adaptive, cognition-driven | Executive perceptions shape strategy | High | RR depends on diversity and cognitive capabilities of leadership teams; highlights bounded rationality |

| Resource Dependence Theory | Interdependent | Managing external ties to secure critical resources | Moderate to high | RR linked to network strategies and ability to reconfigure partnerships under uncertainty |

| Resource-Based View | Resource-centric, partially deterministic | Leveraging valuable, rare, inimitable resources | Moderate | Focuses on robustness via resource control but less on rapid adaptability |

| Dynamic Capabilities | Adaptive and process-driven | Integrating, building, and reconfiguring competences | High | Central for RR: combines robustness and agility to thrive under turbulence |

| Knowledge-Based View | Adaptive, learning-oriented | Creation, sharing, and exploitation of knowledge | High | RR emerges from collective learning and continuous innovation in complex environments |

| Dialectical & Co-evolutionary | Reciprocal causality | Mutual shaping between firm and environment | High | Explains RR as dynamic balance between structural constraints and strategic agency over time |

| Attention-Based View | Adaptive, cognition- and process-driven | Allocation and focus of managerial attention | High | RR enhanced when firms detect weak signals, prioritise critical cues, and mobilise timely responses |

| Option-Based View | Uncertainty-sensitive, flexibility-oriented | Strategic investment in future options | High | Positions RR as a portfolio of adaptive pathways; maintains optionality under deep uncertainty |

| Theory/Perspective | Core Logic/Emphasis | Grain of Analysis | Main RR Stage Supported (Anticipation, Absorption, Adaptation, Managing the New Normal) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organisational ecology | Population-level selection; survival of forms | Industry/population | Anticipation—highlights environmental constraints and vulnerabilities |

| Industrial organisation | Market structure shapes firm conduct and performance | Industry/firm | Anticipation—identifies structural barriers and competitive pressures |

| Neo-institutionalism | Legitimacy and conformity to institutional pressures | Organisation/field | Managing the new normal—explains conformity and persistence under institutional rules |

| Strategic choice | Managerial discretion in shaping strategies | Firm/decision makers | Adaptation—agency and discretion guide proactive change |

| Upper echelons theory | Executive characteristics shape firm outcomes | Top management team | Anticipation & adaptation—cognitive traits condition weak-signal detection and action |

| Resource-based view | Firm resources as source of advantage | Firm | Absorption—buffers shocks by leveraging unique resource stocks |

| Dynamic capabilities | Reconfiguring resources to adapt to change | Firm/process | Adaptation—explicit reconfiguration for renewal |

| Knowledge-based view | Knowledge creation and integration as strategic asset | Firm/team | Absorption & adaptation—supports learning and knowledge application |

| Evolutionary economics | Routines and variation-selection-retention processes | Firm/industry | Managing the new normal—explains gradual renewal and long-term adjustment |

| Attention-based view | Organisational attention shapes strategic action | Organisation/decision | Anticipation—ensures detection and prioritisation of critical signals |

| Option-based reasoning | Investments as real options under uncertainty | Firm/project | Adaptation—guides choices under uncertainty before committing to action |

| Co-evolutionary perspectives | Mutual adaptation between firms and environments | Interorganisational/field | Adaptation & managing the new normal—joint adjustments with partners and ecosystems |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neukam, M.; Muller, E.; Burger-Helmchen, T. Mapping Theoretical Perspectives for Requisite Resilience. Information 2025, 16, 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100854

Neukam M, Muller E, Burger-Helmchen T. Mapping Theoretical Perspectives for Requisite Resilience. Information. 2025; 16(10):854. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100854

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeukam, Marion, Emmanuel Muller, and Thierry Burger-Helmchen. 2025. "Mapping Theoretical Perspectives for Requisite Resilience" Information 16, no. 10: 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100854

APA StyleNeukam, M., Muller, E., & Burger-Helmchen, T. (2025). Mapping Theoretical Perspectives for Requisite Resilience. Information, 16(10), 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100854