Abstract

The adoption of telemedicine among the elderly is vital due to their unique healthcare needs and growing engagement with technology. This study explores the factors influencing their adoption behaviors, identifying both facilitating and inhibiting elements. While previous research has examined these factors, few have empirically assessed the simultaneous influence of barriers and enablers using a sample of elderly individuals. Using behavioral reasoning theory (BRT), this research investigates telehealth adoption behaviors of the elderly in India. A conceptual model incorporates both “reasons for” and “reasons against” adopting telehealth, capturing the nuanced dynamics of adoption behaviors. Data from 375 elderly individuals were collected to validate the model through structural equation modeling. The findings reveal that openness to change significantly enhances attitudes towards telehealth and “reasons for” adoption, influencing behaviors. This research contributes to the healthcare ecosystem by improving the understanding of telehealth adoption among the elderly. It validates the impact of openness to change alongside reasons for and against adoption, refining the understanding of behavior. By addressing impediments and leveraging facilitators, this study suggests strategies to maximize telehealth usage among the elderly, particularly those who are isolated, improving their access to medical services.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and technological advancements have expedited the digital transformation across various industries. In healthcare, this shift has enabled a significant digital revolution in service delivery through the adoption of telehealth [1,2,3]. By utilizing telecommunications technology to strengthen medical treatment and accessibility, telehealth epitomizes a radical change in the way healthcare is delivered [4,5,6,7]. Telehealth was initially developed to provide medical consultations to individuals in remote locations. However, it has evolved into a crucial technology that is integral to modern healthcare systems. Telehealth encompasses a range of services, including real-time video chats, remote consultations, and the exchange of medical data, enabling healthcare delivery that is more flexible, effective, and centered on patient needs. According to the World Health Organization [8], telehealth involves “the delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by health care professionals using Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) to exchange valid information for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease and injuries, as well as for research and evaluation, and the continuing education of health care providers, all aimed at improving the health of individuals and their communities” [8].

According to a 2023 report by the Technology, Information Forecasting and Assessment Council (TIFAC), the telehealth market in India is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 31 percent for the 2020–2025 period and reach a turnover of $5.5 billion. The report says that the increasing demand for teleconsultation, telepathology, teleradiology, and e-pharmacy have acted as the levers for this growth. The first set of official regulations to standardize medical procedures across India was established in 2020 by the Medical Council of India (MCI), the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), NITI Aayog, and the Board of Governors (BoG). This landmark legislation significantly enhanced the accessibility of the nation’s healthcare system, particularly through the expansion of telehealth services. In the Indian context, teleconsultations are primarily facilitated by eSanjeevani, a government-owned service that is offered free of charge [9]. Additionally, there are paid services such as Practo, Apollo 24/7, and others that also provide teleconsultation options [10,11].

While previous research has indicated that telehealth adoption is notably lower among the elderly compared to younger demographics [7,12], advancements in medical facilities and a decrease in mortality rates have led to increased longevity among the elderly. As per the Income-tax Act, India 1961, a senior citizen or elderly is an individual whose age is 60 years or more but less than 80 years. In comparison, a super senior citizen is an individual whose age is 80 years or more. As per the “India Aging Report 2023”, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), in collaboration with the International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS), one-fifth of the population will comprise people above 60 by 2050.

This demographic shift has prompted governments worldwide to prioritize the health of the elderly, developing targeted programs to meet their specific needs [13,14]. Given these factors, there is a pressing need to explore the determinants influencing telemedicine adoption among the elderly. Understanding these factors is critical for crafting interventions that effectively address the barriers and enhance the facilitators to telehealth utilization, ensuring that this increasingly significant demographic can access vital healthcare services.

Hence, in order to attain a thorough understanding of the cognitive processes involved in the adoption of telehealth by the elderly, this research tries to validate both facilitators and inhibitors and their impact on attitude and adoption behavior. By considering the theoretical underpinning of Behavioural Reasoning Theory (BRT) [15], this research examines “reasons for”, “reasons against”, attitudes, adoption behavior, and openness to change as values to understand the adoption of telehealth among the elderly. BRT is preferred in this research due to the limited scope of validating only drivers of existing technology adoption models (i.e., TAM, UTAUT, and IRT). Further, BRT emphasizes context-specific reasons within a single framework, highlighting its targeted approach to understanding behaviors [16,17,18]. BRT further explores additional conceptual linkages through reasons (for and against) to enhance comprehension of human behavior and decision-making [19]. Fourth, BRT highlights the importance of values in adoption and explains the relationships between attitude and actual adoption [20]. Hence, this research tries to answer the following questions:

RQ1: What are the various “reasons for” and “reasons against” the adoption of telehealth by the elderly?

RQ2: Do personal values (openness to change) impact “reasons for”, “reasons against”, and attitudes towards the adoption of telehealth by the elderly?

2. Theoretical Underpinnings

A thorough literature review was conducted to understand telemedicine adoption among the elderly in India. To find relevant articles, the following combination of keywords was considered: (“Telehealth” OR “Telemedicine” AND “Elderly” OR “Adoption” OR “Barriers”). This combination was used within academic databases like “Science Direct”, “Emerald Insights”, “MDPI”, “Google Scholar”, and “Ebsco”. A few duplicates were removed. Further, articles were screened based on quality, and only empirical studies were considered. A few book chapters were also removed due to non-rigorous review. We reviewed the literature in two parts. In the first instance, relevant studies covering the behavioral reasoning theory were examined to gain insight into the theory. Secondly, part of the literature review covered articles concerning telehealth.

2.1. Behavioral Reasoning Theory (BRT)

Understanding behavior toward a novel technology has attained significant attention from researchers in the technology adoption domain. Researchers have extensively validated models like the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Unified Theory of Technology Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT and UTAUT2), and Innovation Resistance Theory (IRT) to understand the adoption of novel technologies but most of these studies have delved into one single perspective, i.e., either drivers [21,22,23] or barriers [24,25]. Therefore, it is crucial to simultaneously evaluate both the motivators facilitating technology adoption and the inhibitors restricting user engagement within a unified research framework to derive meaningful conclusions [19]. Against this backdrop, ref. [15] BRT encompasses both the “reasons for” and “reasons against” the adoption of any new technology. Compared with other technology adoption models, this model was superior as it covered intricated linkages between reasons (for and against adopting a technology), values, attitudes, and technology adoption. Hence, to understand the apprehension of the elderly towards adopting telehealth for their day-to-day routine follow-ups with physicians, this research studies “reasons for” and “reasons against”. BRT has found increased acceptance among researchers to understand the reasons for and against that influence users’ behavioral intentions in different domains. Value and reasoning (reason for and against) are context-specific perceptions that vary depending on the study situation, according to the BRT framework [18,26]. Therefore, by assisting users in making decisions, BRT contributes a more profound knowledge of the elements that influence technology adoption and creates essential connections between attitudes, values, and actual adoption. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that BRT outperforms traditional technology adoption models in explaining diversity in people’s intentions [20]. This provides more assurance to validate BRT about telehealth adoption by the elderly.

Moreover, BRT being contingent and conditional, researchers have the freedom to select the values, “reasons for”, and “reasons against” the adoption of a technology [11,20]. Therefore, we select openness to change as a value impacting the elderly’s adoption of telehealth. In addition, based on the methodology suggested by previous researchers, “reasons for” and “reasons against” were operationalized as second-order reflective constructs in this research [11,19,26].

2.2. Reason for and against Adoption

Telehealth adoption remains slow among the elderly despite the rigorous efforts of the government due to several reasons that are unidentified to date. A few studies (e.g., [3,6,25]) attempted to elicit the reasons associated with the adoption of telehealth. Still, the elderly may have good reasons to refrain from using telehealth, and this study tries to elicit those underlying constraints. A two-step approach was followed to extract the “reasons for” and “reasons against” the adoption of telehealth by the elderly, as extracting the reasons requires vital information along with cognitive thinking. After reviewing the literature, various factors related to telehealth adoption and resistance were identified. These factors were then explored through focus group discussions with the elderly to identify those most relevant to their experiences and needs. A few factors were dropped as per the suggestions from the focus group discussions. As [15] suggested, each focus group member was requested to rate each item on a designed scale ranging from 0 to 3. This cohort helped us to identify the top barriers considered as “reasons against” in this research (lack of empathetic cooperation and social interaction, personal inertia, and technological anxiety) and top facilitators considered as “reasons for” (relative advantage, compatibility, and ease of self-monitoring) in this research. All these constructs were eventually selected based on their significance and literature support from previous studies.

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Value (Openness to Change)

Openness to change is a belief that “motivates people to follow their own intellectual and emotional interest in unpredictable and uncertain directions” [27]. It is based on two sub-dimensions: stimulation, covering diversity and excitement, and self-direction, reflecting the need for individuality and self-sufficiency [28]. The elderly who welcome change and are ready to learn new technologies appreciate telehealth [6]. Users open to change are willing to try new products and do not hesitate to take risks [29]. Hence, users who consider openness to change are early adopters with positive attitudes and a proactive mindset and are ready to adopt a novel technology [30]. Hence, it could be inferred that openness to change will significantly impact the attitude of the elderly towards adopting telehealth.

Previous researchers insisted on attitude as a central construct predicting behavior [11,18,31]. Users develop a positive attitude toward innovation by observing it well-suited to their values [18]. Since this research validates BRT, which underlines that users’ values will impact their attitude towards the adoption of technology, hence we propose that:

H1(a).

Openness to change is positively related to “reasons for” the adoption of telehealth;

H1(b).

Openness to change is negatively related to “reasons against” the adoption of telehealth;

H1(c).

Openness to change is positively related to attitude towards telehealth.

3.2. Attitude and Adoption Behavior

BRT concretely represents positive and negative feelings for certain occurrences and uses attitudes to anticipate decision behavior [15]. There is extant literature available validating the impact of attitude on adoption behavior [26,32,33]. The study by Sivathanu [28] confirmed the positive impact of attitude on adoption behavior among the elderly concerning IoT adoption. Another study by Tandon et al. [12] among the elderly confirmed the effect of attitudes on the continued intention to adopt healthcare apps. Previous studies hypothesized that users’ attitudes towards telehealth positively impact their intention to adopt behavioral intentions [6,34]. In the context of telehealth adoption by the elderly, adoption and behavior demonstrate a favorable attitude, thus impacting users’ adoption behavior. Therefore, increased positive attitudes may lead to repeated use of the technology. Hence:

H2.

The elderly’s attitude towards telehealth impacts their adoption behavior.

3.3. Reasons against the Adoption of Telehealth Adoption among the Elderly

Adopting a novel technology requires significant changes in the behavior and cognitive skills of the users, thereby leading to their acceptance of the technology. However, apprehensions in users’ minds lead to rejection of a technology [11,25]. In this research, the motivation of the elderly to resist the use of telehealth is categorized as a lack of empathetic cooperation and social interaction, personal inertia, poorly designed interface, and technological anxiety.

Empathetic cooperation and social interaction: Shareef et al. [35] validated empathetic cooperation and social interaction, which may be defined as “the level of scope and availability of sympathetically and socially interactive service that develops the perception of esteemed social involvement” [p. 6]. The elderly, while adopting any technology, look for an emotional connection with their healthcare professional. In conventional healthcare, eye contact and general reassurance help build trust between doctors and patients [12,36,37]. This emotional therapeutic relationship is significant for patient satisfaction, thereby playing a major role in patient satisfaction [35]. Telehealth relies upon messaging applications, conversations via telephone, and videoconferencing. Though it is feasible to use modern applications, elderly people prefer face-to-face conversations. Interaction with the latest applications weakens emotional bonds, leading to a sense of emotional detachment from society [37,38].

Technological anxiety: Technological anxiety implies the phobia or nervousness that users experience while switching to a novel technology [35,39]. Elderly people who are less tech-savvy may fear using technology, which may reduce their interest, and thus, may lead them to abandon technology [40]. Navigating through complicated telehealth interfaces and dealing with technical content may perplex them, leading to the avoidance of technology [41]. Previous studies [1,14], considered technological anxiety as a negative emotion and validated its negative impact on adopting a technology. Hence, by considering the opinion of the elderly and support from the previous extant literature, technological anxiety has been validated as a “reason against” technology adoption.

Personal Inertia: Inertia is the tendency to give up on a situation despite the advantages and replacements offered by a specific technology [42]. Even when technology provides more functionality and gives enticement, inertia refers to a person’s aversion to adopting it since they are attached to their current condition [43,44]. When ingrained habits prevent the implementation of innovative tactics, inertia arises in the healthcare setting [12,45]. A previous study by Rahman and Bandyopadhyay [46] considered inertia as a major factor in avoiding innovation. On the other hand, in the study by Tandon et al. [12] on the elderly, inertia emerged as insignificant. Hence, there is a need to validate inertia further concerning novel technologies, especially in the healthcare sector. Due to the status quo, the elderly might not see the benefits of telehealth and thus may prefer to visit healthcare professionals for follow-up visits. Therefore, it is proposed that:

H3(a).

“Reasons against” negatively impact attitude towards Telehealth.

H3(b).

“Reasons against” negatively impact adoption behavior towards telehealth.

3.4. Reasons for the Adoption of Telehealth Adoption among the Elderly

Telehealth differs from conventional healthcare, which is being evaluated by the elderly. When used repeatedly, user behavior is significantly influenced by the relative advantages of telehealth over conventional healthcare [6,26]. The elderly may be willing to adopt new technology due to flexibility and health-related information [26,28]. In this research, in an attempt to determine and assess the factors relevant to telehealth adoption, we selected variables like relative advantage, compatibility, and ease of self-monitoring, which may be considered among the most pertinent telehealth adoption factors among the elderly.

Relative Advantage: Telehealth, though picked up during COVID-19, offers multiple advantages over traditional healthcare systems, such as improved diagnosis, increased accessibility, and reduced waiting time [25,47]. This, in turn, leads to a positive attitude towards telehealth by the elderly living secluded lives either after the death of one partner or their children’s departure [11,26,28]. Further, Chen and Zhang [48] highlighted that reasonable cost, adequate quality, appropriate information, and diverse functions encourage users to adopt healthcare applications to ease routine functions. Thus, when the elderly perceive telehealth as beneficial, they are less likely to express their concern about its adoption. Therefore, relative advantage was considered as a reason for the adoption of telehealth by the elderly.

Compatibility: The extent to which a potential adopter perceives a technological innovation harmonious with the current values, needs, and experiences is recognized as compatibility [49]. However, Tung et al. [50] emphasized compatibility as a major factor influencing adoption behavior. Tsai et al. [1] validated compatibility as a dominant variable influencing telehealth. In another study, Cimperman et al. [51] combined TAM and compatibility among healthcare practitioners. The results of this study indicated a positive impact of compatibility on attitude. Hence, based on the above discussion, we considered compatibility the “reason for” the adoption of telehealth among the elderly in India.

Ease of Self-monitoring: Ease of self-monitoring is a process where the elderly can track their health based on health tracking devices like appliances using telehealth devices. It corresponds to the ease of use of any technology. Self-monitoring is essential in the context of telehealth, particularly for the elderly, who frequently have chronic diseases that need ongoing care [52,53,54]. Technological developments have simplified and increased accessibility to self-monitoring. Self-monitoring due to telehealth has the potential to save healthcare expenditures for the elderly by reducing the need for hospital visits and remote consultations from physicians. Therefore:

H4(a).

Reasons for positively impacting attitude towards telehealth.

H4(b).

Reasons for positive impact adoption behavior towards telehealth.

4. Method

4.1. Instrument

Both “reasons for” and “reasons against” were considered second-order reflective constructs in this research, as suggested by the previous extant literature [11,19]. The scale items of relative advantage and compatibility were adapted from [1,26]. Personal inertia was measured with a scale adapted from Tsai et al. [1] and Tandon et al. [12]. Three items adapted from [54,55] measured the ease of self-monitoring. The studies by Dwivedi et al. [36] and Tandon et al. [12] were mobilized to develop the scale items of empathetic cooperation and social interaction, as well as technological anxiety. The scale items of openness to change and attitude were taken from the previous study by Sivathanu [28]. All the scale items were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1, “Totally disagree”, to 5, “Totally agree”. See Appendix A for more details regarding the specific items of each measured construct.

4.2. Data Collection and Sample

Since the sample considered in this research comprised the elderly, data were collected using non-probability sampling techniques. Non-probability sampling methods are common in technology adoption studies [1,6]. We considered the threshold that Bentler and Chou [56] proposed to determine the sample size where a N/Q ratio of 5:1 was proposed. Therefore, a sample size of 375 was used in this study to improve the generalizability of the model. A two-step approach was followed for data collection. The scale items from diverse studies were consolidated as a questionnaire during the first step. This questionnaire was shared with three doctors, five elderly, and four academicians for face and content validity. This group suggested minor changes in the language, which were incorporated. After this, the questionnaire was piloted with 45 elderly people and 10 doctors practicing telehealth. The Cronbach’s Alpha scores indicated reliability values of more than 0.7 for all the constructs. Hence, no item was deleted, and we initiated the actual data collection process. In conducting this research, we adhered strictly to the ethical guidelines established by the first author’s institution. All the necessary approvals and permissions were obtained to collect data, and we ensured that all institutional and legal standards were met. This research was based on measuring the perception of the elderly, which included collecting their views, experiences, and opinions without altering their behavior. Experimentations require different ethical considerations, but since no experiment was conducted in the framework of this study, this specific requirement did not apply. In this case, informed consent was obtained from the hospitals before contacting the respondents. Additionally, before asking any questions, we comprehensively explained the study’s objectives and procedures and assured them of the anonymity of responses. We also assured them that this study was conducted only for academic purposes and ensured voluntary participation. Both online and offline modes were used to collect data. An online Google Form was created and circulated through social media and hospitals. Data were collected in multiple ways. We considered both personal visits and online mediums for the collection of data. We visited elderly homes, hospitals, NGOs, and various medical camps organized primarily for the elderly. The elderly were also contacted online by sending the forms to various WhatsApp groups.

We also requested the elderly to provide referrals among their peers who regularly take teleconsultations. We received 398 forms, of which 375 were considered for further analysis. A few forms were eliminated as they were incomplete, and most of the questions were left blank. Some forms showing outlier values, like an age of more than 200, were also removed. The research was conducted from March 2024 to May 2024.

4.3. Initial Data Quality Checks

We carried out several preliminary quality tests on data. The first step involved looking for missing values of less than 1% in the data. The arithmetic mean was used in place of these values [57]. We encouraged respondents to answer the questionnaire honestly by assuring them that their responses would stay confidential and the data would only be used for scholarly research, which helped to counteract the social desirability bias—comparing the early and late responders allowed for the additional testing of non-response bias. The absence of substantial disparities in the descriptive statistics suggests that non-response bias is not a problem in this sample. Common method bias (CMB) was addressed by Harman’s single-component test. The test resulted in a single factor variance of 23.97%, below the prescribed threshold value of 50.00%, thus indicating the absence of CMB.

5. Results and Findings

Data were analyzed using AMOS version 23. Co-variance-based SEM (CB-SEM) was preferred in this research to validate the hypothesized model due to the refractive nature of the constructs. Firstly, the measurement model was validated through reliability and validity, followed by SEM to validate the proposed hypotheses.

5.1. Measurement Model

First, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to measure standardized loadings, reliability, content validity, and discriminant validity to arrive at the measurement mode. The item loadings of all the items were above the recommended threshold of 0.6 [58]. Similarly, the Average Variance Extracted, Composite Reliability, and Cronbach’s Alpha values of all the constructs exceeded the prescribed threshold of 0.5 and 0.7, respectively (Table 1). Discriminant validity was assessed, and the square root of all the constructs was more than the inter-item correlations (Table 2). Thus, after obtaining sufficient validity and reliability, the data appeared appropriate to evaluate the path correlations.

Table 1.

Measurement model.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity.

5.2. Structural Model

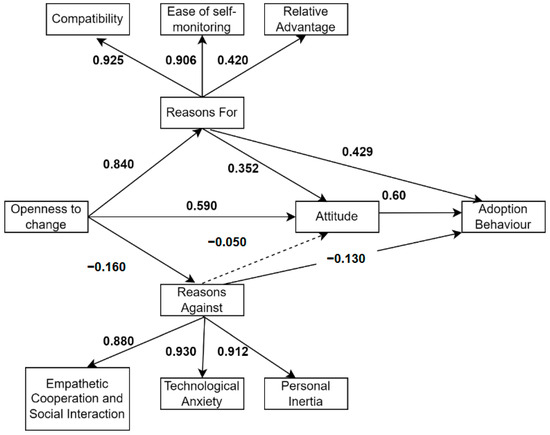

Table 3 and Figure 1 show the structural model results indicating the path coefficients of the hypothesized relationships. SEM analysis revealed that the majority of hypotheses were supported. Explicitly, reasons for positively influence the elderly’s attitude towards telehealth (β = 0.352, p = 0.015), while reasons against indicate a negative but insignificant impact on the attitude towards telehealth (β = −0.050, p = 0.362). However, the impact of reasons against was significantly negative on adoption behavior (β = −0.13, p = 0.024). Reasons for had a significant and positive impact on adoption behavior (β = 0.429, p = 0.001). Moving on to personal values, we considered openness to change as a personal value in this research. Openness to change strongly impacted reasons for (β = 0.840, p = 0.001) and had a negative, significant but lower impact on reasons against (β = −0.16, p = 0.04) compared to reasons for. Attitude strongly impacted the adoption of telehealth among the elderly (β = 0.840, p = 0.001).

Table 3.

Path Analysis.

Figure 1.

Results of hypotheses testing.

Regarding second-order relationships, predictors of reasons for had a stronger relationship compared to reasons against. Compatibility emerged as the strongest predictor of reasons for (β = 0.925, p = 0.001), followed by ease of self-monitoring (β = 0.906, p = 0.001) and relative advantage (β = 0.20, p = 0.000). Among the reasons against, technological anxiety attained the highest loadings (β = 0.930, p = 0.001), followed by personal Inertia (β = 0.912, p = 0.000) and lack of empathetic cooperation and social interaction (β = 0.880, p = 0.000), which had albeit lower loadings. The model fit indices indicated an acceptable alignment with the following values: CMIN/df = 2.684, GFI = 0.898, NFI = 0.904, CFI = 0.937, TLI = 0.926, IFI = 0.937, and RMSEA = 0.067.

6. Conclusions

By considering the theoretical underpinning of BRT, this research tries to validate the attitude and adoption behavior of telehealth adoption among the elderly by taking a sample from India. This study validates the diverse paths, including “reasons for” and “reasons against” the adoption of AI in healthcare.

In response to the first research question, i.e., understanding “reasons for” and “reasons against” various reasons in both the domains were validated. Among the “reasons for”, compatibility emerged as the strongest reason for the adoption of telehealth by the elderly, and this is supported by previous research [1,51]. This was followed by ease of self-monitoring, a finding supported by previous studies [53,54]. Among all the “reasons for”, relative advantage emerged as significant but had the least loadings, which is in sync with the previous literature [26,59]. This may be because the elderly using telehealth are well-versed in the advantages of telehealth and consider other factors more important. The key reasons for rejecting telehealth among the elderly were technological anxiety, personal inertia, and lack of empathetic cooperation, and social interaction. Technological anxiety emerged as the strongest inhibitor, and previous studies supported this finding [1,35,39]. This was followed by personal inertia, which also supports the findings of previous research studies on healthcare [45,46].

Moving further, the research findings differ from the previous studies where, interestingly, “reasons against” have an insignificant impact on attitude, thus contradicting the conclusions of earlier studies [19,28]. However, “reasons for” have a significant positive impact on adoption behavior [26,28,32,33].

The ”reasons for” demonstrated a significant positive impact on attitude and adoption behavior, and the findings align with previous research studies [11,31]. This reflects the fact that reasons for craft attitude while technology adoption is driven by context-specific factors. Moreover, the path coefficient illustrates that the reasons for have notably higher loadings compared to the arguments against, suggesting that the former has a greater influence than the latter.

Furthermore, the significant impact of openness to change as a personal value in the context of telehealth reinforces reasons for the adoption of telehealth by the elderly. This finding conforms to the previously reported research [6,28,29]. This research confirms previous studies’ well-established causal association between values and attitudes (e.g., [31,60,61]. After the COVID-19 pandemic, several efforts have been made by world governments, especially in India, to reach out to patients through several telehealth initiatives. However, the penetration of these programs remains slow, and telehealth has not been able to penetrate [62,63,64,65]. Healthcare providers search for various strategies to deliver healthcare to those who cannot obtain treatment due to geographical and infrastructural barriers, as highlighted in the previous studies [25,66]. Since relative advantage emerged as significant in this research, a few studies consider it an essential factor for a few studies in the specific Indian context [65,67]. Telehealth is a service innovation move due to convenience, cost-effectiveness, and flexibility, making it more patient-centric [68]. Yadav et al. [11] confirmed relative advantage, and compatibility as drivers, and technological anxiety as impediments in the context of mobile healthcare apps. Though researchers in India have studied telehealth by taking diverse populations, yet there are limited studies specifically targeting the elderly in the context [65,69,70], but a comprehensive model is still needed to understand the drivers as well as barriers to getting an in-depth understanding of the telehealth adoption in India.

7. Implications of This Study

This research has implications for academicians and researchers trying to conduct research on telehealth, as well as policymakers, in devising adequate strategies for implementing telehealth, especially with respect to the elderly.

First, this study extends BRT in the context of telehealth with respect to the elderly. This validity of reasons for and reasons against provides valuable insights and develops an all-inclusive model covering vital problems explicitly related to the elderly living a secluded life. This validation of “reasons for” and “reasons against” in a single study adds to the prevailing realm of knowledge, where most of the previous studies have relied on either drivers [6] or barriers [25] or based on the validation of TAM [71]. The model established by this research, validating reasons for and reasons against attitude, adoption behavior, and openness to change as a value, helps the researchers comprehend the decision-making process of the elderly. Understanding an extensive series of constructs in an all-inclusive model is vital and can help learn the elderly’s behavior regarding telehealth.

This research has practical implications for policymakers and organizations that are handling telehealth implementation. The research results indicate that openness to change is strongly related to “reasons for” the adoption of telehealth. Hence, it becomes imperative that service providers elaborate on the benefits of telehealth to generate awareness among the elderly for the frequent use of telehealth in their day-to-day routine self-monitoring. Telehealth may be positioned as an important service, especially for the secluded elderly, and it may be portrayed as a need-of-the-hour service. This might lead to its repeated use for health monitoring.

As compatibility and ease of self-monitoring emerged significantly in this research, the implication is that service providers must develop easy-to-understand telehealth procedures. Further, telehealth applications may be improved with enhanced functionality features like quick navigation and gamified applications. These may, in turn, cause technological anxiety to emerge significantly in this research. In this research, the lack of empathetic cooperation and social interaction emerged as one of the strong barriers; hence, healthcare professionals providing telehealth consultations need to be empathetic, offer a further element of attachment, and develop social relationships with the elderly. This will, in turn, remove the barriers and make telehealth a routine procedure for the elderly.

Thus, it may be concluded that though the elderly are open to change and willing to adopt telehealth, they still need assistance to overcome barriers like personal inertia and technological anxiety. This may be due to a change in the lifestyle after COVID-19 and the compatibility with the existing healthcare system. Yet, they need a human touch to overcome the apprehensions that emerged dominant through this research. The reasons for and against that emerged as significant in this study are significant for academicians seeking to enhance their research in telehealth, for healthcare organizations using telehealth for patient treatment and online consultations, and for service providers to design telehealth equipment with easy-to-understand features.

8. Limitations and Future Scope

This study has limitations related to the sample selected, i.e., we considered only the elderly from India in this sample. Future studies may replicate this model in developed countries as there may be a difference in technological exposure and facilities among the elderly in these countries. Future studies may compare the perceptions of young, middle-aged, and elderly regarding telehealth adoption. The “reasons for” and “reasons against” may be validated across specific illnesses and injuries requiring a different procedure. A notable example would be chronic illnesses. Besides, this conceptual model may be modified according to culture, norms, and values. Further, a mixed-method research design could be conducted to identify further insights into the domain. In addition, this research has taken only one stakeholder as a sample, and future research studies may compare the perceptions of healthcare professionals treating patients through telehealth with those of patients receiving regular treatment through telehealth. Although past research has shown that specific technologies, such as peer-to-peer online health communities (OHCs) favour patient compliance [72], it remains unclear whether telehealth fosters similar outcomes. Future research could, therefore, investigate the impact of telehealth on patient compliance and on its determinants, including patient empowerment, patient satisfaction, and patient commitment [72]. Finally, user-involved design of digital health products is on the rise [73], and future research could investigate the modalities of elderly user involvement in the design of telehealth and its influence on satisfaction, commitment, and compliance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.T.; methodology, U.T.; software, U.T.; validation, U.T., M.E. and M.S.; formal analysis, U.T.; investigation, U.T., M.E. and M.S.; resources, M.E.; data curation, U.T.; writing—original draft preparation, U.T.; writing—review and editing, M.E., M.S. and M.K.; visualization, M.E., M.S. and M.K.; supervision, M.E.; project administration, U.T.; funding acquisition, M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived by the Chitkara Business School Ethics Committee, for this study, due to the fact that the study did not involve an experimental study design. As per the institutional guidelines, only experiments require ethical approval at the first author’s institution where the study was conducted.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Scale Items and Their Source | |

|---|---|

| Main Construct | Indicator/Item |

| Relative Advantage | Compared to personal visits to the doctor, telehealth can save money. |

| Compared with offline health services, getting teleconsultation on time is more convenient for me. | |

| Compared with offline health services, I think telehealth services (such as appointments, medical treatment, and taking medicine) are more efficient. | |

| Compatibility | The service provided by telehealth can satisfy my demands regarding health management. |

| [1] | Services provided by telehealth connect with my daily life. |

| Applying telehealth services does not create any conflicts with my living habits. | |

| Ease of Self-monitoring | The instructions provided for self-monitoring through telehealth are clear. |

| [54,55] | I can easily access support if I encounter difficulties with self-monitoring using telehealth. |

| The instructions provided for self-monitoring through telehealth are easy to understand. | |

| Value of openness to change | I always look for new things in telehealth to do. |

| [18] | I look for adventure while using telehealth. |

| I am open to new experiences. | |

| Personal Inertia | I will continue to apply traditional physical measurement tools because they are part of my life. |

| [1,12] | Even though traditional physical measurement tools are not effective, I will continue to apply them. |

| I am already used to these traditional physical measurement tools. | |

| Technological Anxiety | I feel afraid to use telehealth. |

| [1] | I feel nervous about using telehealth. |

| I feel uncomfortable using telehealth. | |

| Empathetic Cooperation and Social Interaction | Using telehealth weakens my emotional bonds with healthcare providers. |

| [12,35] | Telehealth decreases my scope to interact socially. |

| I feel social detachment while using telehealth. | |

| Attitude | I feel comfortable using telehealth. |

| [1] | Using telehealth provides lots of benefits over the conventional healthcare system. |

| Using telehealth in the near future adds a lot of value. | |

| Adoption Intention | I will use telehealth in the near future. |

| [1] | I will try to replace my current physical mode of health checkup with telehealth. |

| I plan to use telehealth. | |

References

- Tsai, J.M.; Cheng, M.J.; Tsai, H.H.; Hung, S.W.; Chen, Y.L. Acceptance and resistance of telehealth: The perspective of dual-factor concepts in technology adoption. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, V.H.; Dastidar, B.G.; Suri, S.; Jani, A.R. Perspectives and use of telemedicine by doctors in India: A cross-sectional study. Health Policy Technol. 2024, 13, 100845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Zakkariya, K.A.; Peethambaran, M. Predicting virtual care continuance intention in the post-Covid world: Empirical evidence from an emerging economy. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2023, 16, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimi, M.; Goren, U.; Grossman, Z. Barriers and challenges to telemedicine usage among the elderly population in Israel in light of the COVID-19 era: A qualitative study. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241240235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turcotte, S.; Bouchard, C.; Rousseau, J.; DeBroux Leduc, R.; Bier, N.; Kairy, D.; Dang-Vu, T.T.; Sarimanukoglu, K.; Dubé, F.; Bourgeois Racine, C.; et al. Factors influencing older adults’ participation in telehealth interventions for primary prevention and health promotion: A rapid review. Australas. J. Ageing 2024, 43, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Tandon, U.; Kumar, H. Understanding medical service quality, system quality and information quality of Tele-Health for sustainable development in the Indian context. Kybernetes 2023. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.M.; Jacobs, J.; Yefimova, M.; Greene, L.; Heyworth, L.; Zulman, D.M. Virtual care expansion in the Veterans health administration during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical services and patient characteristics associated with utilization. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Global Observatory for eHealth. Telemedicine: Opportunities and Developments in Member States: Report on the Second Global Survey on eHealth; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44497 (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Sajid, M.; Zakkariya, K.A.; Surira, M.D.; Thomas, L. Why are Indian Digital Natives Resisting Telemedicine Innovation Resistance Theory Perspective. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Generalla, J.; Thompson, B.; Haidet, P. Facilitating the feedback process on a clinical clerkship using a smartphone application. Acad. Psychiatry 2017, 41, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Giri, A.; Chatterjee, S. Understanding the users’ motivation and barriers in adopting healthcare apps: A mixed-method approach using behavioral reasoning theory. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 183, 121932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, U.; Ertz, M.; Shashi. Continued Intention of mHealth Care Applications among the Elderly: An Enabler and Inhibitor Perspective. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, M.S.; Laato, S.; Islam, A.N.; Bao, Y. Continued use intention of wearable health technologies among the elderly: An enablers and inhibitors perspective. Internet Res. 2021, 31, 1611–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.G.; DiNitto, D.M.; Marti, C.N.; Choi, B.Y. Telehealth use among older adults during COVID-19: Associations with sociodemographic and health characteristics, technology device ownership, and technology learning. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2022, 41, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westaby, J.D. Behavioral reasoning theory: Identifying new linkages underlying intentions and behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 98, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virmani, N.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S. Adoption of industry 4.0 evidence in emerging economy: Behavioral reasoning theory perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 188, 122317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalicic, L.; Weismayer, C. Consumers’ reasons and perceived value co-creation of using artificial intelligence-enabled travel service agents. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudy, M.C.; Garcia, R.; O’Driscoll, A. Consumer resistance to innovation—A behavioral reasoning perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Koshta, N.; Goyal, R.K.; Sakashita, M.; Almotairi, M. Behavioral reasoning theory (BRT) perspectives on E-waste recycling and management. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaby, J.D.; Probst, T.M.; Lee, B.C. Leadership decision-making: A behavioral reasoning theory analysis. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banbury, A.; Smith, A.C.; Mehrotra, A.; Page, M.; Caffery, L.J. A comparison study between metropolitan and rural hospital-based telehealth activity to inform adoption and expansion. J. Telemed. Telecare 2023, 29, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, X.; Burtch, G. Healthcare across boundaries: Urban-rural differences in the consequences of telehealth adoption. Inf. Syst. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Chua, J.Y.; Li, X.; Wang, X. The determinants of users’ intention to adopt telehealth: Health belief, perceived value and self-determination perspectives. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarabyat, I.A.; Al-Nsair, N.; Alrimawi, I.; Al-Yateem, N.; Shudifat, R.M.; Saifan, A.R. Perceived barriers to effective use of telehealth in managing the care of patients with cardiovascular diseases: A qualitative study exploring healthcare professionals’ views in Jordan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, S.; Tandon, U. Understanding barriers of telemedicine adoption: A study in North India. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2022, 39, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H. Exploring the adoption decisions of mobile health service users: A behavioral reasoning theory perspective. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 2241–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sivathanu, B. Adoption of Internet of things (IOT) based wearables for healthcare of older adults–a behavioural reasoning theory (BRT) approach. J. Enabling Technol. 2018, 12, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, P.; Wach, D.; Costa, S.; Moriano, J.A. Values matter, Don’t They?–combining theory of planned behavior and personal values as predictors of social entrepreneurial intention. J. Soc. Entrep. 2019, 10, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G.; Van der Werff, E.; Lurvink, J. The significance of hedonic values for environmentally relevant attitudes, preferences, and actions. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Gupta, A.; Dixit, S.; Kumar, H. Knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding COVID-19: A cross-sectional study among rural population in a northern Indian District. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 4769–4773. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Li, C.; Guo, J.; Zhao, G. An investigation into the adoption behavior of mhealth users: From the perspective of the push-pull-mooring framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Qian, L. Understanding the potential adoption of autonomous vehicles in China: The perspective of behavioral reasoning theory. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 669–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, X.; Ye, G. Understanding the keyword adoption behavior patterns of researchers from a functional structure perspective. Scientometrics 2024, 129, 3359–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, M.A.; Kumar, V.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kumar, U.; Akram, M.S.; Raman, R. A new health care system enabled by machine intelligence: Elderly people’s trust or losing self control. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 162, 120334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Malina, L.; Dzurenda, P.; Srivastava, G. Optimized blockchain model for Internet of things based healthcare applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 42nd International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Budapest, Hungary, 1–3 July 2019; pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, R.K.; Badger, K.; Barton, K.L.; Kohut, M.; Clark, M. The implementation of telemedicine in the COVID-19 Era. J. Maine Med. Cent. 2021, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber, S.; McNaughton, R.B. Resilience and entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 1129–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.A.; Shafiq, M.; Kakria, P. Investigating acceptance of telemedicine services through an extended technology acceptance model (TAM). Technol. Soc. 2020, 60, 101212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, P. Willingness to use telemedicine for psychiatric care. Telemed. J. e-Health 2004, 10, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Z.; Khalid, K. The adoption of M-government services from the user’s perspectives: Empirical evidence from the United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia-Palacios, L.; Pérez-López, R.; Polo-Redondo, Y. Enemies of cloud services usage: Inertia and switching costs. Serv. Bus. 2016, 10, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, W.; Zeckhauser, R. Status quo bias in decision making. J. Risk Uncertain. 1988, 1, 7–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polites, G.L.; Karahanna, E. Shackled to the status quo: The inhibiting effects of incumbent system habit, switching costs, and inertia on new system acceptance. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.V.; Das, S. Medical practitioner’s adoption of intelligent clinical diagnostic decision support systems: A mixed-methods study. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Bandyopadhyay, S. An observable effect of spin inertia in slow magneto-dynamics: Increase of the switching error rates in nanoscale ferromagnets. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2021, 33, 355801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Muff, A.; Meschiany, G.; Lev-Ari, S. Adequacy of web-based activities as a substitute for in-person activities for older persons during the COVID-19 pandemic: Survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X. How environmental uncertainty moderates the effect of relative advantage and perceived credibility on the adoption of mobile health services by Chinese organizations in the big data era? Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2016, 2016, 3618402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Lessons for guidelines from the diffusion of innovations. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Improv. 1995, 21, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, F.C.; Chang, S.C.; Chou, C.M. An extension of trust and TAM model with IDT in the adoption of the electronic logistics information system in HIS in the medical industry. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2008, 77, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asua, J.; Orruño, E.; Reviriego, E.; Gagnon, M.P. Healthcare professional acceptance of telemonitoring for chronic care patients in primary care. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2012, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.V.; Sethares, K.A. Facilitators and barriers to the adoption of telehealth in older adults: An integrative review. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2014, 32, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimperman, M.; Brenčič, M.M.; Trkman, P.; Stanonik, M.D.L. Older adults’ perceptions of home telehealth services. Telemed. e-Health 2013, 19, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, C.; Fohn, J.; Wilson, N.; Patlan, E.N.; Zipp, S.; Mileski, M. Utilization barriers and medical outcomes commensurate with the use of telehealth among older adults: Systematic review. JMIR Med. Inform. 2020, 8, e20359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Xiao, L.; Blonstein, A.C. Measurement of self-monitoring web technology acceptance and use in an e-health weight-loss trial. Telemed. e-Health 2013, 19, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentler, P.M.; Chou, C.-P. Practical Issues in Structural Modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiheydari, N.; Delgosha, M.S.; Olya, H. Scepticism and resistance to IoMT in healthcare: Application of behavioural reasoning theory with configurational perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 169, 120807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.; Yun, J.; Yu, S. My smart speaker is cool! Perceived coolness, perceived values, and users’ attitude toward smart speakers. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 560–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N.; Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Tan, T.M.; Alharbi, F. Behavioral reasoning perspectives to brand love toward natural products: Moderating role of environmental concern and household size. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Hafeez-Baig, A.; Gururajan, R.; Chakraborty, S. Conceptual framework for telehealth adoption in Indian healthcare. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference of the Asia Pacific Decision Sciences Institute: Full Papers, Asia-Pacific Decision Sciences Institute (APDSI), New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–25 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chellaiyan, V.G.; Nirupama, A.Y.; Taneja, N. Telemedicine in India: Where do we stand? J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 1872–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandachi, D.; Dang, B.N.; Lucari, B.; Teti, M.; Giordano, T.P. Exploring the attitude of patients with HIV about using telehealth for HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2020, 34, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, R. Telehealth and COVID-19: Using technology to accelerate the curve on access and quality healthcare for citizens in India. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, M.; Mittal, A. Employees’ change in perception when artificial intelligence integrates with human resource management: A mediating role of AI-tech trust. Benchmarking Int. J. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplaga, M. A cross-sectional study assessing determinants of the attitude to the introduction of eHealth services among patients suffering from chronic conditions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2015, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, S.; Mittal, A.; Marwah, S. Service innovation, corporate reputation and word-of-mouth in the banking sector: A test on multigroup-moderated mediation effect. Benchmarking Int. J. 2020, 27, 406–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasekaba, T.M.; Pereira, P.; Rani, G.V.; Johnson, R.; McKechnie, R.; Blackberry, I. Exploring telehealth readiness in a resource limited setting: Digital and health literacy among older people in Rural India (DAHLIA). Geriatrics 2022, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, B.S.; Shalini, S.P.; Rao, Y.M.; Hedberg, P.; Liljegren, P.D.; Edin-Liljegren, A. Challenges for Technology Adoption Towards Primary Geriatrics Services. DY Patil J. Health Sci. 2022, 10, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.; Warshaw, P. Technology acceptance model. J. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-Pontevia, A.F.; Menvielle, L.; Ertz, M. Effects of three antecedents of patient compliance for users of peer-to-peer online health communities: Cross-sectional study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menvielle, L.; Ertz, M.; François, J.; Audrain-Pontevia, A.F. User-Involved Design of Digital Health Products. In Revolutions in Product Design for Healthcare: Advances in Product Design and Design Methods for Healthcare; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).