Empowering Pedestrian Safety: Unveiling a Lightweight Scheme for Improved Vehicle-Pedestrian Safety

Abstract

1. Introduction

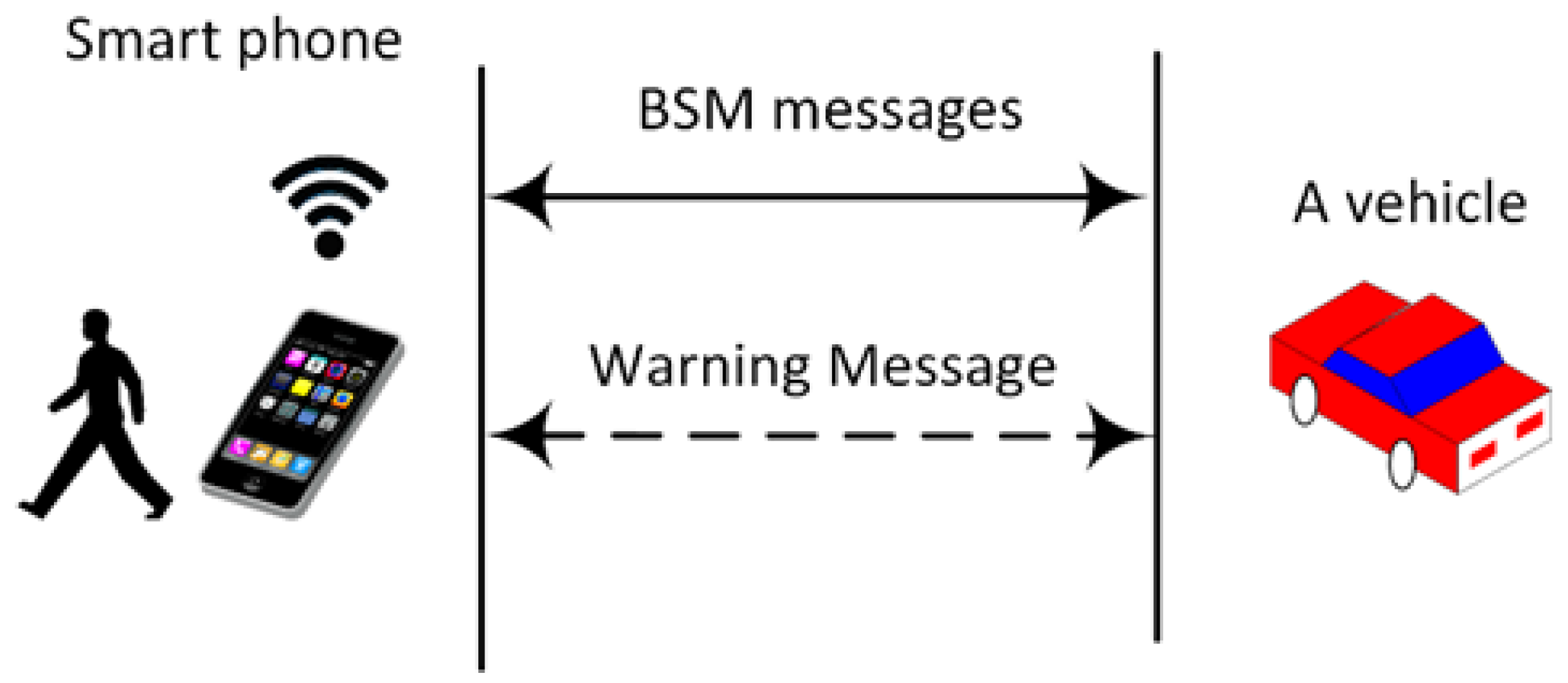

- We build up on our previous V2P lightweight scheme [21] by enhancing an efficient VANET-based pedestrian protection scheme based on vehicle-to-pedestrian (V2P) communication between smart vehicles and vulnerable road users’ smartphones. Consequently, our scheme contributes to a decrease in road collisions and casualties that are likely to occur, and roads are anticipated to become safer as a result.

- We show the efficiency of our scheme through simulations and implementations to meet the real-time constraints of V2P communications in different traffic scenarios. We measured critical network parameters in terms of average throughput, processing delay, and network load.

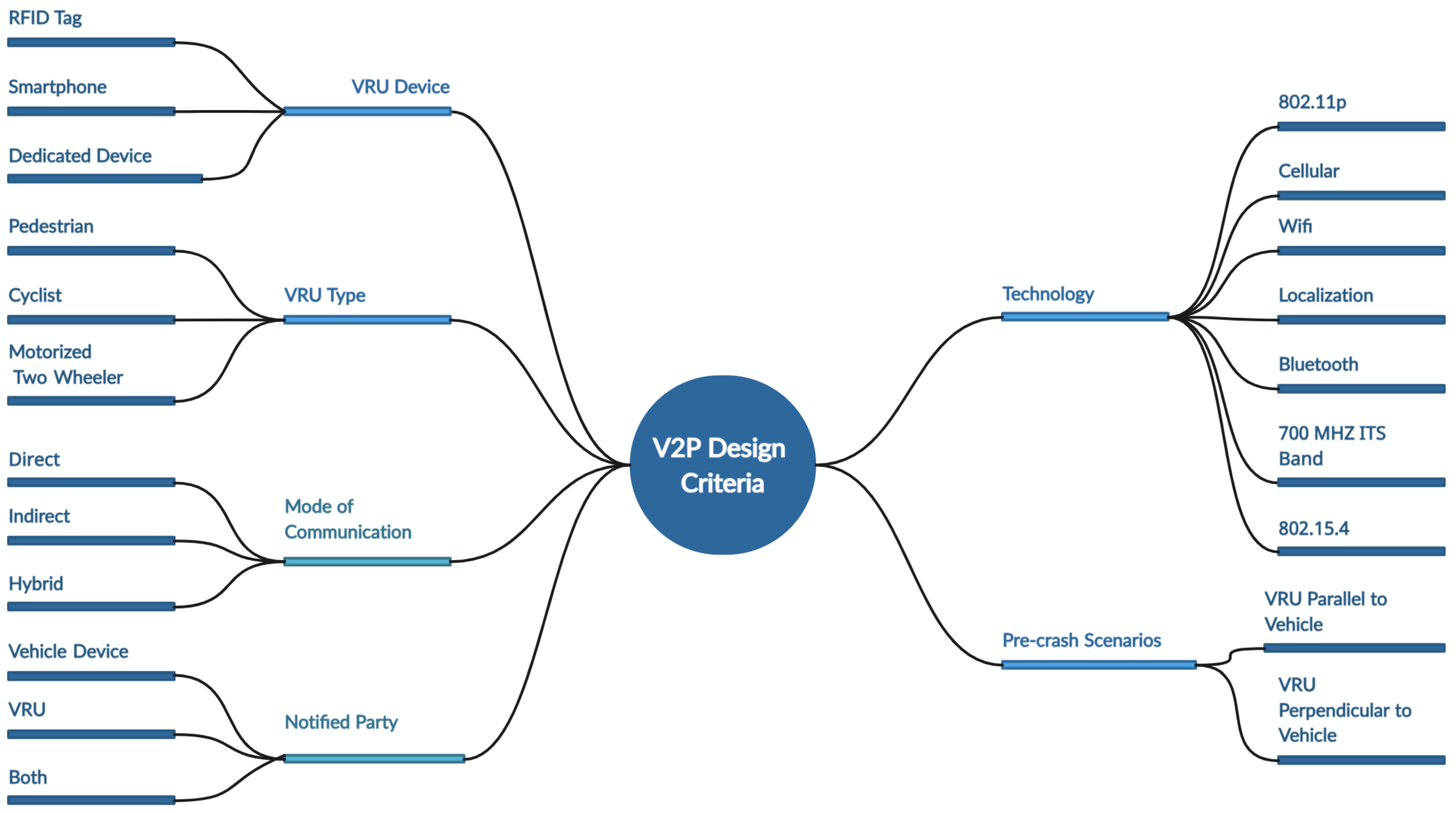

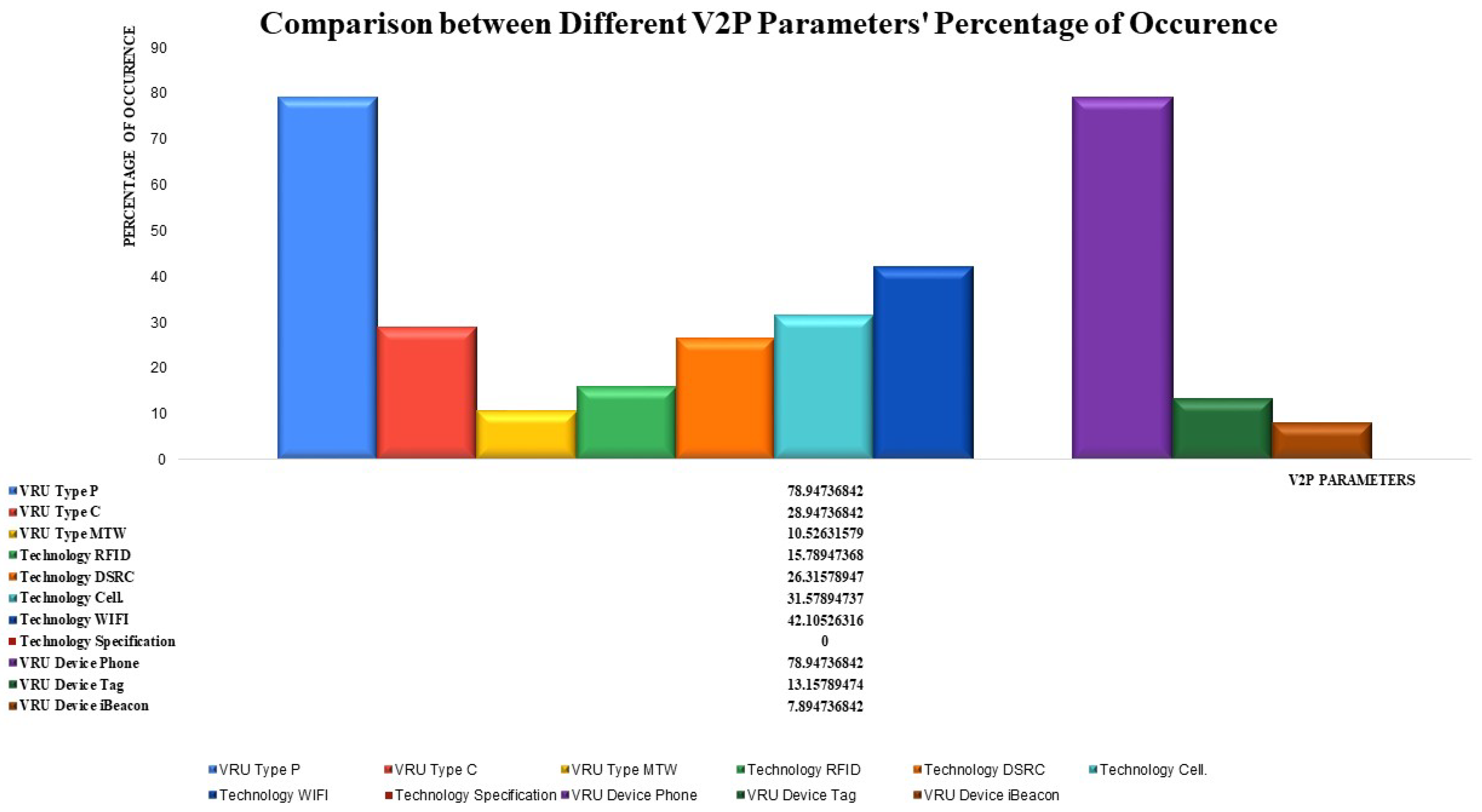

- We compare the different technologies used in V2P system design in terms of range, latency, and ease of deployment in our related work and study the factors that influence V2P system design specifications, like VRU types, VRU roles, VRU devices, communication technologies, notified parties, and purpose.

2. Proposed Vulnerable Road Users Protection Scheme

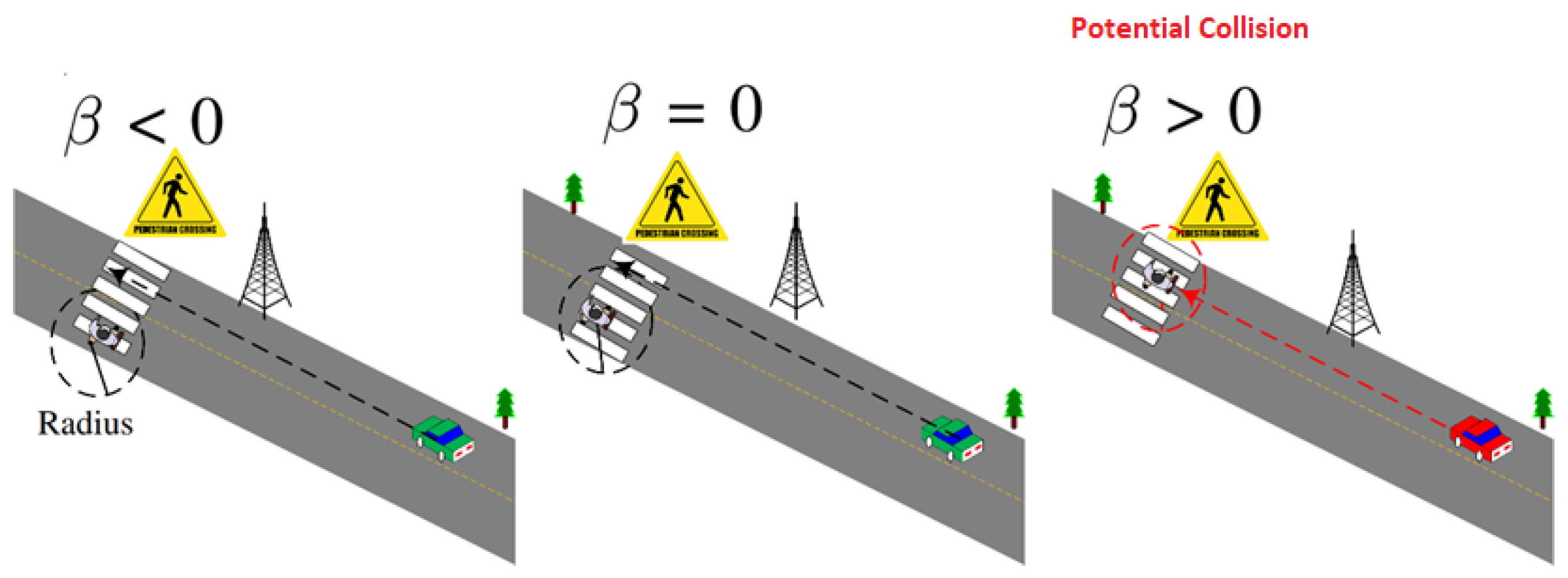

Scheme Overview and Network Model

| Algorithm 1 Efficient Collision Detection Algorithm (CDA) |

|

3. Simulation

3.1. Simulation Setup

- Low traffic scenario: 50 vehicles/10 pedestrians;

- Average traffic scenario: 100 vehicles/30 pedestrians;

- High traffic scenario: 145 vehicles/60 pedestrians.

3.2. Simulation Metrics

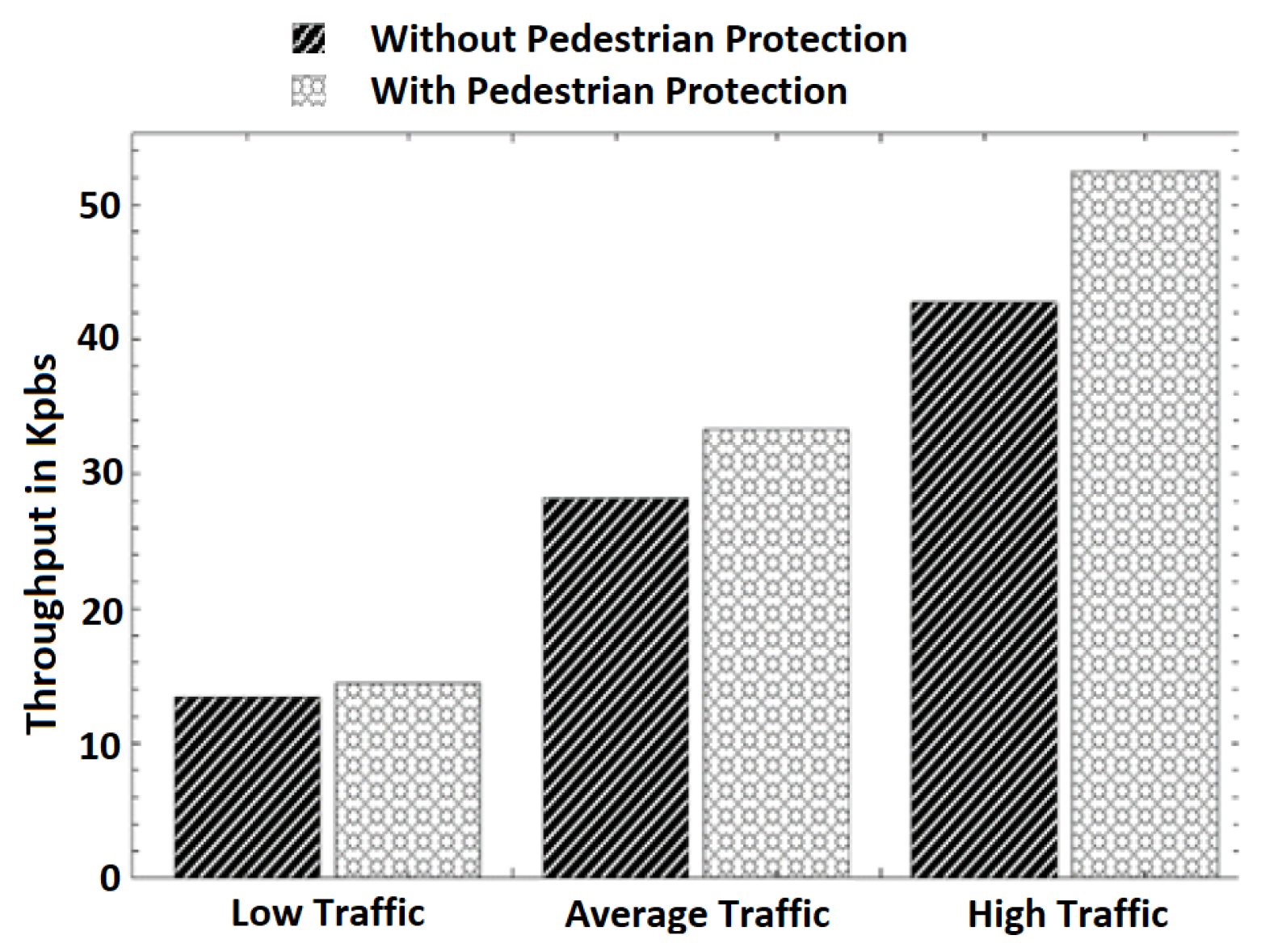

- Average throughput: The average amount of data in Kbps received by vehicles/pedestrians per second. This is an important metric for measuring the required bandwidth and assessing the feasibility of the proposed scheme.

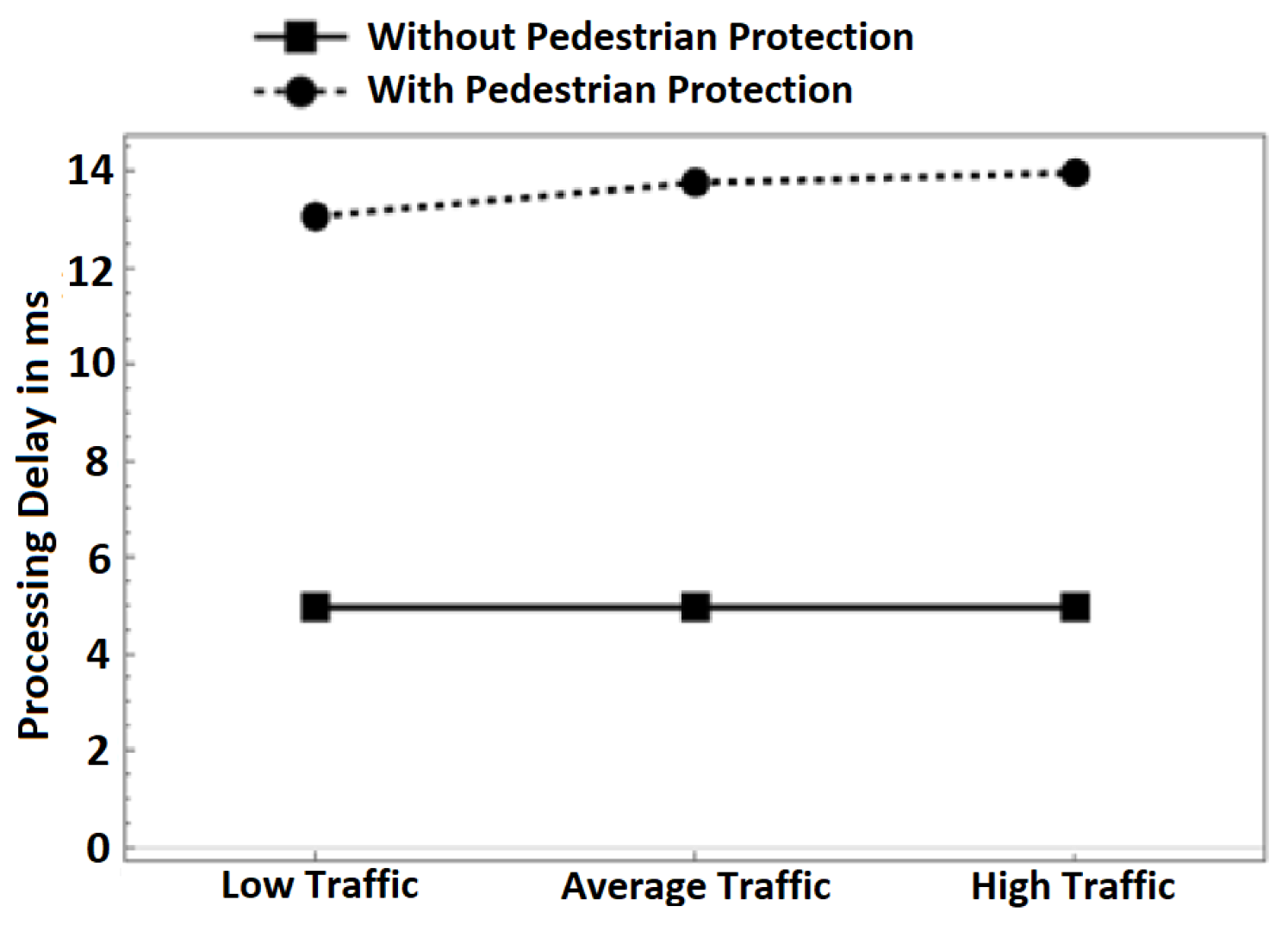

- Processing delay: This is the average time it takes to run our proposed scheme and send a reply back to the sender. For example, when a vehicle receives a BSM message from a pedestrian, it runs our scheme and sends a warning message if it detects a collision. The processing delay is the time between the reception of the BSM message and the transmission of the warning message.

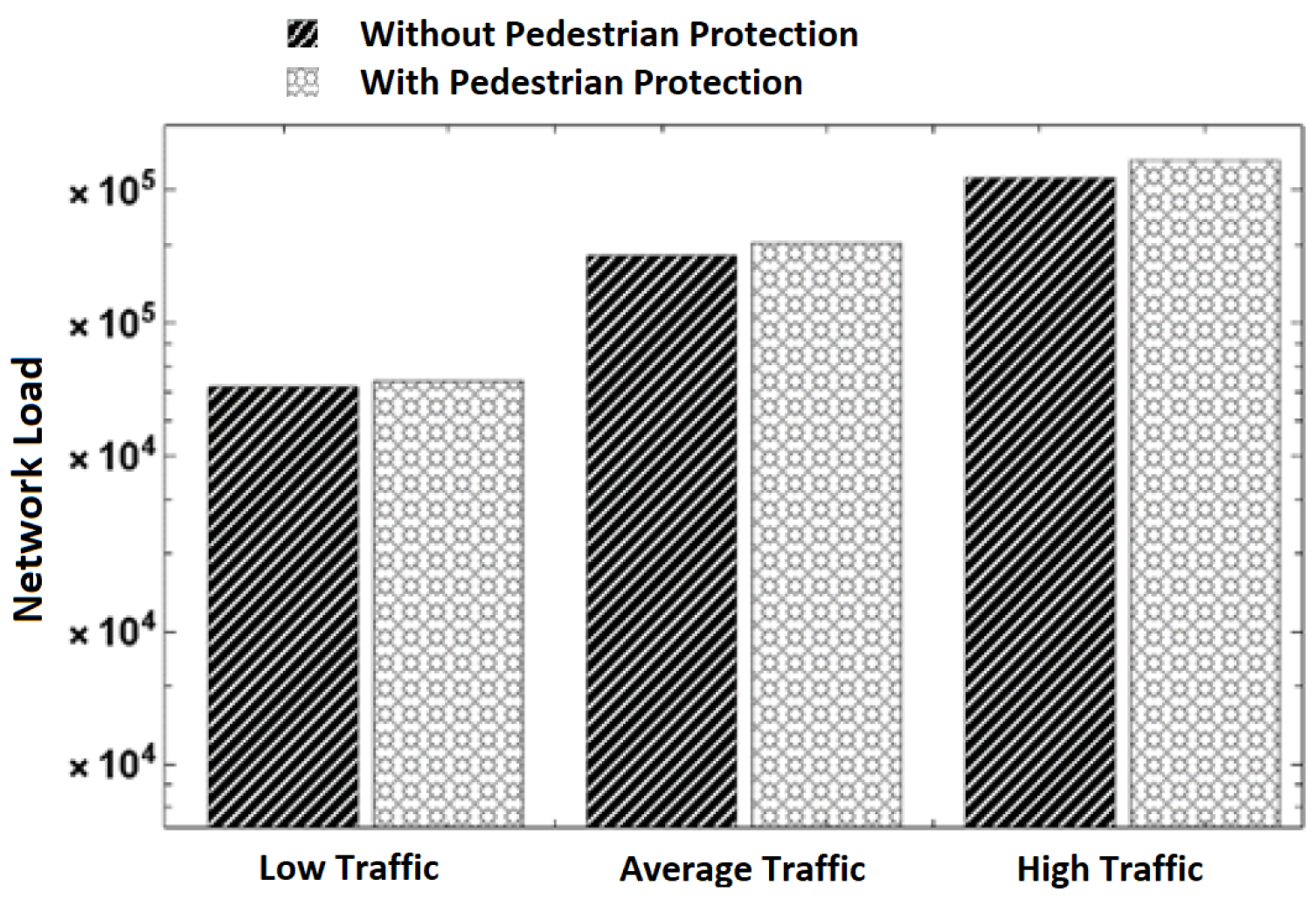

- Network load: This is the total number of packets sent by vehicles and pedestrians within the simulation time.

3.3. Simulation Results

- Average throughput: The average throughput at different traffic scenarios is presented in Figure 6 It can be observed that the throughput increases with an increase in the number of vehicles and pedestrians in both schemes. In different traffic scenarios, the throughput’s increase is expected because the number of transmissions increases as the number of vehicles and pedestrians grows. We observed that our scheme introduces slightly more throughput in all traffic scenarios than the pure V2V scheme. This is because pedestrians’ engagement in communication with vehicles introduces more transmission and the reception of data. However, the increase in the throughput introduced by our scheme is minimal. For example, it can be observed that the throughputs of the pure V2V scheme and the scheme with pedestrian protection in the average traffic scenario are 28.21 and 33.28 Kbps, respectively. This is a 15% throughput increase introduced by our scheme for pedestrian safety. In addition, the throughput increase is only 8% in the low-traffic scenario.

- Processing delay: Figure 7 depicts the average processing delay. We differentiate between the delay in both schemes: with pedestrian protection and without pedestrian protection. In the pedestrian protection scheme, we run our scheme after the verification process of BSM messages. In the other scheme, we only run the verification process of BSM messages. We set the verification time of BSM messages to be 4.97 ms according to [24,25]. As observed in the following Figure 7, the delay introduced by both schemes is almost constant in all traffic scenarios, even with increasing the number of nodes in the high-traffic scenario. We observe that in our scheme, the processing delay times are 13.07, 13.77, and 13.97 ms in all traffic scenarios. Without pedestrian protection, the delay times are 4.97 ms for the same traffic scenarios. The introduced delay by our scheme is only 8 ms, which is a minimal cost and proves that our scheme is lightweight and fits well in VANET safety applications. More importantly, the delay is far below 100 ms even in dense traffic scenarios, which meets the minimum latency requirements of VANET safety applications according to [26,27].

- Network load: The number of packets transmitted throughout the simulation time at different traffic scenarios is shown in Figure 8. It can be observed that the number of packets increases with an increase in the number of vehicles and pedestrians involved in communication. This is normal behavior because of the increase in packet transmission. When comparing the pure V2V scheme with our scheme, we can observe that our scheme has more packets transmitted. We attribute the increase in transmitted packets to the pedestrians’ communication with vehicles. The increase in network load due to the use of our scheme is negligible. For example, our scheme transmits 73,967 packets while the pure V2V scheme transmits 71,712 packets in the low-traffic scenario. This is an increase in the transmission of 2255 packets only (3%), which is a small bandwidth cost for protecting pedestrians.

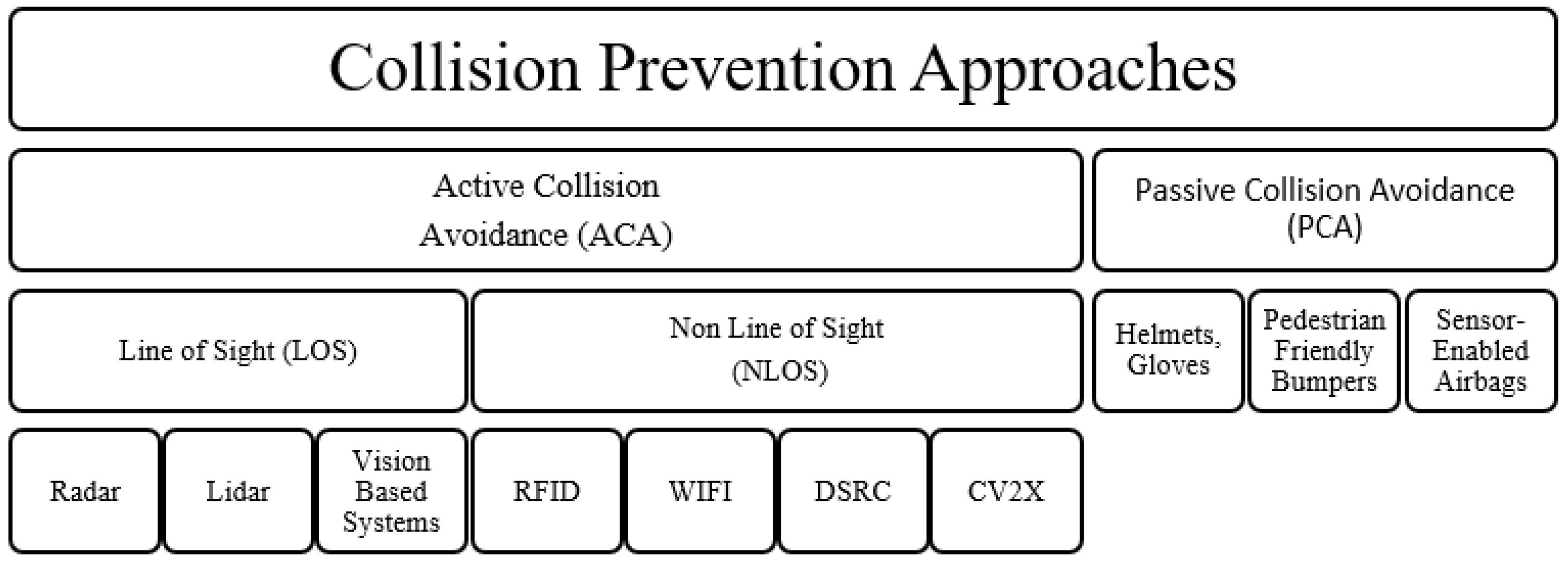

4. Related Work

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Future Work

- The study of the effect of including a synchronization server in our V2P system to measure the expected delay;

- We will study different behaviors of pedestrians to consider the differences in their patterns of motion (like children, elderly pedestrians, and disabled pedestrians);

- We will include different types of vulnerable road users other than pedestrians, like cyclists and motorized two-wheelers in our study.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garcia-Roger, D.; Gonzalez, E.E.; Martín-Sacristán, D.; Monserrat, J.F. V2X support in 3GPP specifications: From 4G to 5G and beyond. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 190946–190963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, R.S.; Brodie, C. Road safety evidence review: Understanding the role of speeding and speed in serious crash trauma: A case study of New Zealand. J. Road Saf. 2022, 33, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakim, L.L.; Ghani, N.A. A review of road traffic hazard and risk analysis assessment. Environment 2022, 7, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatality Facts 2020 Yearly Snapshot. 2020. Available online: https://www.iihs.org/topics/fatality-statistics/detail/yearly-snapshot (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Malone, K.; Silla, A.; Johansson, C.; Bell, D. Safety, mobility and comfort assessment methodologies of intelligent transport systems for vulnerable road users. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2017, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Road Traffic Injuries. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Gandhi, T.; Trivedi, M.M. Pedestrian protection systems: Issues, survey, and challenges. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2007, 8, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.C.; Harris, M.A.; Teschke, K.; Cripton, P.A.; Winters, M. The impact of transportation infrastructure on bicycling injuries and crashes: A review of the literature. Environ. Health 2009, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanparijs, J.; Panis, L.I.; Meeusen, R.; De Geus, B. Exposure measurement in bicycle safety analysis: A review of the literature. Accid Anal. Prev. 2015, 84, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, T.; Ngo, V.L.; Nguyen, H. Design of pedestrian friendly vehicle bumper. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2010, 24, 2067–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumos. Ride the Brightest with a LUMOS Helmet, 2020. Available online: https://ridelumos.com/ (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Zackees. Zackees Turn Signal Gloves 2.0. 2020. Available online: https://www.bicycling.com/bikes-gear/g34706221/10-cutting-edge-gifts-for-tech-loving-cyclists-1605659452/ (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Hovding. The World’s Safest Bicycle Helmet Isnt a Helmet. 2020. Available online: https://hovding.com/ (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Constant, A.; Lagarde, E. Protecting vulnerable road users from injury. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, J.J.; Merdrignac, P.; Shagdar, O.; Nashashibi, F.; Naranjo, J.E. Vehicle to pedestrian communications for protection of vulnerable road users. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium Proceedings, Dearborn, MI, USA, 8–11 June 2014; pp. 1037–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Heinovski, J.; Stratmann, L.; Buse, D.S.; Klingler, F.; Franke, M.; Oczko, M.C.H.; Sommer, C.; Scharlau, I.; Dressler, F. Modeling Cycling Behavior to Improve Bicyclists’ Safety at Intersections—A Networking Perspective. In Proceedings of the IEEE 20th International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks(WoWMoM), Washington, DC, USA, 10–12 June 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Habibovic, A.; Davidsson, J. Causation mechanisms in car-to-vulnerable road user crashes: Implications for active safety systems. Accid Anal. Prev. 2012, 49, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, K.F.; Wang, C.; Feng, Y.; Tian, Y.C. Time synchronization in vehicular ad-hoc networks: A survey on theory and practice. Veh. Commun. 2018, 14, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, J.; Silva, L.; Fernandes, B.; Almeida, J.; Ferreira, J. Empowering Vulnerable Road Users in C-ITS. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 9–13 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johan Scholliers, M.v.S.; Moerman, K. Integration of vulnerable road users in cooperative ITS systems. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2017, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabieh, K.; Aydogan, A.F.; Azer, M.A. Towards Safer Roads: An Efficient VANET-based Pedestrian Protection Scheme. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Communications, Computing, Cybersecurity, and Informatics (CCCI), Beijing, China, 15–17 October 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NS3. The Network Simulator NS3. Available online: https://www.nsnam.org/ (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- SUMO. Simulation of Urban Mobility (SUMO) Documentation. Available online: https://sumo.dlr.de/docs/Tools/Trip.html (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Petit, J.; Mammeri, Z. Authentication and consensus overhead in vehicular ad hoc networks. Telecommun. Syst. 2013, 52, 2699–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, J. Analysis of ecdsa authentication processing in vanets. In Proceedings of the 2009 3rd International Conference on New Technologies, Mobility and Security, Cairo, Egypt, 20–23 December 2009; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Ma, D.; Regan, A. TARI: Meeting delay requirements in VANETs with efficient authentication and revocation. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Wireless Access in Vehicular Environments (WAVE), Shanghai, China, 21–22 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chantaksinopas, I.; Lee, W.; Prayote, A.; Oothongsap, P. Delay-sensitive applications in vanet and seamless connectivity: The limitation of UMTS network. Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2012, 12, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, I.; Jiménez, F.; Calderón, M.; Naranjo, J.E.; Anaya, J.J. Reducing unnecessary alerts in pedestrian protection systems based on p2v communications. Electronics 2019, 8, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashdan, I.; de Ponte Müller, F.; Jost, T.; Sand, S.; Caire, G. Large-scale fading characteristics and models for vehicle-to-pedestrian channel at 5-GHz. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 107648–107658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béduneau, G.; Jaber, G.; Ducourthial, B. A method for predicting ITS cooperative applications performances. Comput. Netw. 2022, 216, 109148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, T.; Yáñez, A.; Umaña, S.C.; Hafid, A.S. Impact of safety message generation rules on the awareness of vulnerable road users. Sensors 2021, 21, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komamiya, W.; Tang, S.; Obana, S. Radiation angle estimation and high-precision pedestrian positioning by tracking change of channel state information. Sensors 2020, 20, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, M.; Ding, Z. A VRU Collision Warning System with Kalman-Filter-Based Positioning Accuracy Improvement. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Information Communication and Software Engineering (ICICSE), Chengdu, China, 19–21 March 2021; pp. 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, Z.; Zaidan, A.; Ahmed, M.A.; Bahaa, B.; Albahri, O.; Alamoodi, A.; Malik, R.; Albahri, A.; Ameen, H.; Garfan, S.; et al. An approach to pedestrian walking behaviour classification in wireless communication and network failure contexts. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 8, 909–931. [Google Scholar]

- Botache, D.; Dandan, L.; Bieshaar, M.; Sick, B. Early Pedestrian Movement Detection Using Smart Devices Based on Human Activity Recognition. In INFORMATIK 2019: 50 Jahre Gesellschaft für Informatik—Informatik für Gesellschaft (Workshop-Beiträge); Gesellschaft für Informatik eV: Bonn, Germany, 2019; pp. 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morold, M.; Nguyen, Q.H.; Bachmann, M.; David, K.; Dressler, F. Requirements on delay of VRU context detection for cooperative collision avoidance. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 92nd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Fall), Victoria, BC, Canada, 18 November–16 December 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q.H.; Morold, M.; David, K.; Dressler, F. Car-to-Pedestrian communication with MEC-support for adaptive safety of Vulnerable Road Users. Comput. Commun. 2020, 150, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang-Huy, N.; Michel, M.; Klaus, D.; Falko, D. Adaptive Safety Context Information for Vulnerable Road Users with MEC Support. In Proceedings of the 15th Annual Conference on Wireless On-Demand Network Systems and Services (WONS), Wengen, Switzerland, 22–24 January 2019; pp. 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Malinverno, M.; Avino, G.; Casetti, C.; Chiasserini, C.F.; Malandrino, F.; Scarpina, S. MEC-based collision avoidance for vehicles and vulnerable users. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.05299. [Google Scholar]

- Babar, M.; Tariq, M.U.; Almasoud, A.; Alshehri, M. Privacy-Aware Data Forensics of VRUs Using Machine Learning and Big Data Analytics. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2021, 2021, 3320436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabil, A.; Rabieh, K.; Kaleem, F.; Azer, M.A. Vehicle to Pedestrian Systems: Survey, Challenges and Recent Trends. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 123981–123994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasbi-Sarvestani, A.; Nourkhiz Mahjoub, H.; Fallah, Y.P.; Moradi-Pari, E.; Abuchaar, O. Implementation and Evaluation of a Cooperative Vehicle-to-Pedestrian Safety Application. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2017, 9, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewalkar, P.; Seitz, J. Vehicle-to-Pedestrian Communication for Vulnerable Road Users: Survey, Design Considerations, and Challenges. Sensors 2019, 19, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rettenmaier, M.; Schulze, J.; Bengler, K. How Much Space Is Required? Effect of Distance, Content, and Color on External Human-Machine Interface Size. Information 2020, 11, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, V.; Chang, C.M.; Javanmardi, E.; Nakazato, J.; Lin, P.; Igarashi, T.; Tsukada, M. Fostering Fuzzy Logic in Enhancing Pedestrian Safety: Harnessing Smart Pole Interaction Unit for Autonomous Vehicle-to-Pedestrian Communication and Decision Optimization. Electronics 2023, 12, 4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerra, E.M.; Shoman, M.; Imine, H.; Brasile, C.; Lantieri, C.; Vignali, V. The Visual Behaviour of the Cyclist: Comparison between Simulated and Real Scenarios. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter Name | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of lanes | 1 lane/direction | ||

| Map area | 600 × 600 m | ||

| Lane width | 2 m | ||

| Transmission range | 500 m | ||

| Data rate | 27 Mb/s | ||

| Average runs | 30 | ||

| Warning message | 50 Bytes | ||

| Traffic scenarios | Low traffic | Average traffic | High traffic |

| 50 vehicles/10 pedestrians | 100 vehicles/30 pedestrians | 145 vehicles/60 pedestrians | |

| Vehicle velocities | Vary in the range of 65–85 km/h | ||

| Maximum simulation time | 300 s | ||

| Basic safety message (BSM) interval | 200 ms | ||

| Basic safety message (BSM) size | 254 bytes | ||

| Challenge | Description | Efforts | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context Information Exchange |

|

|

|

| Precise Pedestrian Positioning |

| There are three types of solutions:

|

|

| Network Congestion |

|

|

|

| Energy Efficiency |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rabieh, K.; Samir, R.; Azer, M.A. Empowering Pedestrian Safety: Unveiling a Lightweight Scheme for Improved Vehicle-Pedestrian Safety. Information 2024, 15, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15030160

Rabieh K, Samir R, Azer MA. Empowering Pedestrian Safety: Unveiling a Lightweight Scheme for Improved Vehicle-Pedestrian Safety. Information. 2024; 15(3):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15030160

Chicago/Turabian StyleRabieh, Khaled, Rasha Samir, and Marianne A. Azer. 2024. "Empowering Pedestrian Safety: Unveiling a Lightweight Scheme for Improved Vehicle-Pedestrian Safety" Information 15, no. 3: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15030160

APA StyleRabieh, K., Samir, R., & Azer, M. A. (2024). Empowering Pedestrian Safety: Unveiling a Lightweight Scheme for Improved Vehicle-Pedestrian Safety. Information, 15(3), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15030160