Critical Factors and Practices in Mitigating Cybercrimes within E-Government Services: A Rapid Review on Optimising Public Service Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Critical Factors and Management Practices

1.2. Public Service Management

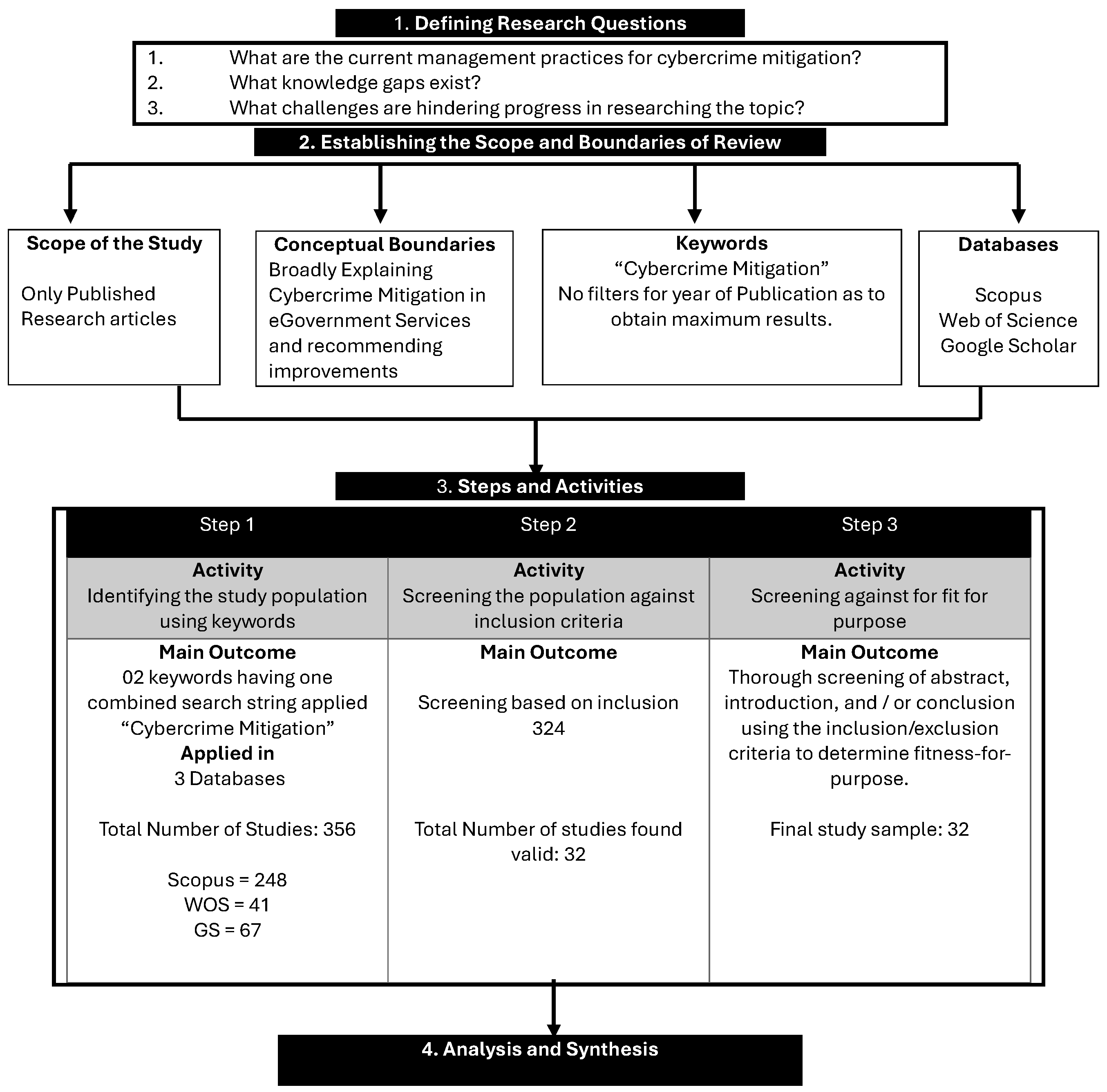

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Extracting Factors

| Technical | Managerial | Behavioural | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. No | Source | Cybersecurity Frameworks | Data Recording | Event Logging | Manage IT Risk | Monitor Network | Access Control | Centralise Cybersecurity | Training | Awareness | Policy | Audit | Resources | Collaboration | Legal Response | Top Management Support | Learning from Incidents | Monitoring Performance | Cyber Insurance | Compliance | Criminal Behaviour |

| 1 | [29] | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | [2] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | [30] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | [27] | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | [31] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 | [32] | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | [33] | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | [34] | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | [35] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||

| 10 | [36] | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | [37] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||

| 12 | [38] | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | [39] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| 14 | [40] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

| 15 | [41] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | [42] | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | [43] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||

| 18 | [44] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

| 19 | [45] | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | [46] | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | [47] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||

| 22 | [48] | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | [49] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

| 24 | [50] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||

| 25 | [51] | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | [52] | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||||

| 27 | [4] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||

| 28 | [53] | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||||

| 29 | [54] | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||||

| 30 | [55] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||||

| 31 | [56] | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||

| 32 | [57] | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||||

3.2. Extracting Theoretical Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Stream I (Technical)

- Cybersecurity Frameworks

- Data recording and event logging

- Manage IT Risk

- Network Monitoring

- Access Control

- Centralised Cybersecurity

4.2. Research Stream II (Managerial)

- Training

- Awareness

- Policy

- Audit

- Resources

- Collaboration

- Legal Response

- Top Management Support

- Learning from Incidents

- Monitoring Performance

- Cyber Insurance

4.3. Research Stream III (Behavioural)

- Compliance

- Criminal Mindset

4.4. Theoretical Underpinning of Studies

- Individual-level theories

- Institutional-Level Theories

4.5. Knowledge Gaps and Challenges

4.6. Theoretical Contribution

5. Conclusions

Future Research Recommendations

- Management perspective studies in cybercrime mitigation within e-government services, provided the study is context-specific (regional, institutional or problem-oriented).

- Development of a theory of cybercrime prevention within the e-government services domain or information system security domain, including human intervention.

- Checking the feasibility of results from one study to other different contexts to understand their viability, especially in the lower development index of countries identified in the UN e-government survey [21].

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| S. No | Source | Findings | Population | Theory | Context | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [57] | Expats collaborate with local accomplices to commit economic cybercrimes, particularly focusing on money laundering through false identification and sham companies to launder money. | Ghanaians in US | N/A | Economic cybercrime | Content Analysis |

| 2 | [48] | Increasing awareness in students can reduce cybercrimes. | Students in Jordan, higher education institutes | N/A | Impact of awareness | Quantitative |

| 3 | [46] | Awareness and data safety campaigns from governments must be initiated. | US, Singapore and India | N/A | Comparing essential elements to mitigate cybercrimes | Quantitative |

| 4 | [32] | Awareness is important to adopt technology; however, government initiatives and legal awareness have limited influence in adoption of preventive behaviour. | Smart city population in India | UTAT Model | Mitigate cybercriminal activities | Quantitative |

| 5 | [27] | It is crucial to identify and enhance cooperative relationships between state-based law enforcement and private sector initiatives in law enforcement. | Regulatory bodies and private industry | N/A | Law enforcement for prevention | Review |

| 6 | [45] | Despite existing anti-cybercrime and anti-money-laundering legislation, weaknesses of global regulations and state-level enforcement are issues. | Case laws and policy documents | AML Model | Cybercrime law and best practices to reduce weaknesses | Document Analysis |

| 7 | [50] | To cater for cybercrime challenges, the government should revise criminal and procedural laws, strengthen electronic device security measures and enhance training and awareness among law enforcement and administrative officials. | Indonesia | N/A | Legal framework of cybercrime prevention | Qualitative Descriptive |

| 8 | [49] | A decision support framework assists in understanding the impact of cyber fraud, which further assists in deciding the sector where prevention and mitigation can deliver most effect, for instance, on profitability, goodwill, customers’ satisfaction or risk management. | 17 licensed banks in South Africa | N/A | Adaptive response policy | Analytical Hierarchy Process |

| 9 | [56] | The study suggests an inclusive policy framework that incorporates legal, governance, internal control and regulatory elements aimed at strengthening cybersecurity within South African banks. | Professionals of South African banking sector | FMLC | Cyberfraud mitigation in banking | Mixed Method |

| 10 | [51] | Frequent training and government alerts may also be important for cyberattack prevention. | Financial executives from UAE banks | Protection Motivation Theory | Cyberattack prevention in UAE using leadership | Quantitative |

| 11 | [52] | The research underscores the importance of tailored punishments to deter cybercrimes and ensure fairness in legal responses to technology-related offences. | Laws of UK, USA, China, Ethiopia and Pakistan | Deterrence Theory | Punishment of cybercriminals | Review |

| 12 | [54] | Cybersecurity is the key element of mitigating the risk and incidents of cybercrime. Targeted educational initiatives and policy measures can enhance cybercrime prevention. | General population in USA | Routine Activity Theory | Cybersecurity knowledge and awareness | Quantitative |

| 13 | [55] | The strategies of policy updates, system modifications, partnerships, new software integration, enhanced training, security improvements and rigorous monitoring aim to ensure a cybersafe environment now and in future crises. | Cybersecurity experts and top managers in Australia | Learning Loop Framework | Cybersecurity challenges in higher education | Qualitative |

| 14 | [33] | Regulatory frameworks must be strengthened to enforce mandatory cybersecurity standards and regular audits across financial institutions, fostering collaborative efforts between banks, regulatory bodies and law enforcement agencies. | Administration-level employees inPakistan | N/A | Impact on performance of banking sector | Quantitative |

| 15 | [34] | Use of cyber insurance to manage financial risks associated with cyber incidents and collaborative efforts between public and private sectors can enhance national cybersecurity resilience. | Collaboration of reviewers from India and the USA | Risk Management Theories | Model selection for threat mitigation | Review |

| 16 | [31] | Resources for implementing cybersecurity measures in e-government portals. Collaboration to centralise cybersecurity in small cities. | China | Socio-Technical Analysis | E-Government development from public value perspective | Qualitative |

| 17 | [41] | The operational aspects of information security in e-government are inherently complex, which contributes to the limited amount of scientific research dedicated to this field. | Ukraine | N/A | Review of country’s information legislation | Review |

| 18 | [42] | E-government has shown a notable correlation with increased commitments to cybersecurity and business utilisation. | 127 countries | Quantitative | ||

| 19 | [43] | The standard operating procedures developed by NIST and ISO for cybersecurity are important. The major vulnerabilities are weak security systems, lack of awareness and enterprise failure. | Saudi Arabia | N/A | E-government cyberthreats and vulnerabilities | Mixed Method |

| 20 | [30] | Policy, training, audits and compliance are regarded to be the best management practices. Organisations must be up to date with industry standards and information security management. | India | N/A | Information security management practices | Case Study |

| 21 | [44] | NIST management practices are important, stressing thorough data recording and registration to reduce failure. | Italy | NIST Framework | Cyber resilience using managerial practices | Qualitative |

| 22 | [35] | ISO controls can be used as guidelines for managerial practices in information security management. | N/A | N/A | Guidelines for enhancing IS management | Review |

| 23 | [40] | Importance of bridging socio-technical gaps in cybersecurity frameworks to achieve effectiveness. Recommendations include adopting integrated management processes, ensuring compliance with regulatory standards and fostering continuous improvement in cybersecurity practices across governmental and organisational levels. | Global context | Socio-Technical Systems | Optimising cybersecurity practices as a socio-technical management process | Mixed Method Research |

| 24 | [2] | The study suggests that information security should be considered the responsibility of management, and further notes that information security managers should consider a holistic approach. | N/A | N/A | Information security management practices | Review |

| 25 | [38] | The NIST framework can be used for cybersecurity self-evaluation within SMEs. Government can encourage SMEs to use the NIST framework and enhance national cyber resilience. | N/A | NIST Framework | Cybersecurity evaluation tool for SMEs | Quantitative |

| 26 | [39] | The NIST framework constitutes cybersecurity management practices which are important to structure the processes and information security of an organisation. | Cybersecurity experts in Germany | Conceptual | Information security factors | Qualitative |

| 27 | [47] | Implementing technical measures, senior management in cybersecurity governance, strengthening regulatory frameworks, conducting regular training programmes for employees, fostering collaboration among stakeholders, investing in cybersecurity infrastructure and integrating insights from institutional theory into cybersecurity strategies. | Technology department staff members and e-government officials in Jordanian ministries | HOT Framework, Institutional Theory | Cybersecurity enhancement in public sector organisations | Quantitative |

| 28 | [4] | Cybersecurity is a shared responsibility, involving not just governments but also organisations and individuals. A unified effort from all stakeholders can effectively combat cybercrime. | Global | N/A | Cybersecurity tactics in mitigating cybercrimes | Mixed Method |

| 29 | [36] | Lessons from advanced nations can help mitigate electronic tax cybercrimes. Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa should establish strong institutions to monitor and address cyber tax crimes effectively. | Nigeria and South Africa | N/A | Crime in electronic taxation | Review |

| 30 | [53] | The government needs to develop relevant anti-cybercrime laws with stringent penalties, as well as cybercrime policies tailored for the business sector. Additionally, law enforcement officers must be trained to bridge the skills gap currently hampering their response to cybercrime. | 38 retail players in Zimbabwe | Routine Activity Theory | Cybercrimes in developing third world | Mixed Method |

| 31 | [37] | Particularly in the context of Pakistan, management and resources are deemed more important for the success of e-government services than social and economic factors. | Multiple agencies in Pakistan | Critical Success Factors | E-government Success in Pakistan | Mixed |

| 32 | [29] | Incident management trainings should be initiated by government. | N/A | N/A | Incident management practices | Review |

References

- Reddick, C.; Anthopoulos, L. Interactions with e-government, new digital media and traditional channel choices: Citizen-initiated factors. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2014, 8, 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, Z.A.; Shah, M.H.; Ahmed, J. Information security management needs more holistic approach: A literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.H.; Jones, P.; Choudrie, J. Cybercrimes prevention: Promising organisational practices. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.; Ojelade, I.; Taiwo, E.; Obunadike, C.; Oloyede, K. Cyber-Security Tactics in Mitigating Cyber-Crimes: A Review and Proposal. Int. J. Cryptogr. Inf. Secur. IJCIS 2023, 13. Available online: https://airccse.org/journal/ijcis/current2023.html (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- McLaughlin, M.D.; Gogan, J. Challenges and best practices in information security management. MIS Q. Exec. 2018, 17, 237–262. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, B. Enhancing the effectiveness of cybercrime prevention through policy monitoring. J. Crime Justice 2019, 42, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malodia, S.; Dhir, A.; Mishra, M.; Bhatti, Z.A. Future of e-Government: An integrated conceptual framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, C.M.; Nurse, J.R.C.; Franqueiraand, V.N.L. Learning from cyber security incidents: A systematic review and future research agenda. Comput. Secur. 2023, 132, 103309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganin, A.A.; Quach, P.; Panwar, M.; Collier, Z.A.; Keisler, J.M.; Marchese, D.; Linkov, I. Multicriteria Decision Framework for Cybersecurity Risk Assessment and Management. Risk Anal. 2020, 40, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, G.P. Fifteen years of e-government research in Ibero-America: A bibliometric analysis. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzy, M.; Ibrahim, B. The evolution of e-government research over two decades: Applying bibliometrics and science mapping analysis. Libr. Hi Tech 2022, 42, 227–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.K.; Thong, J.Y.; Brown, S.A.; Venkatesh, V. Design characteristics and service experience with e-government services: A public value perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2025, 80, 102834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Kim, J.H.; Mathiassen, L.; Moore, R. DATA BREACH MANAGEMENT: AN INTEGRATED RISK MODEL. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djotaroeno, M.; Beulen, E. Information Security Awareness in the Insurance Sector: Cognitive and Internal Factors and Combined Recommendations. Information 2024, 15, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobensack, M.; von Gerich, H.; Vyas, P.; Withall, J.; Peltonen, L.-M.; Block, L.J.; Davies, S.; Chan, R.; Van Bulck, L.; Cho, H.; et al. A rapid review on current and potential uses of large language models in nursing. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 154, 104753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garritty, C.; Gartlehner, G.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; King, V.J.; Hamel, C.; Kamel, C.; Affengruber, L.; Stevens, A. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 130, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Antony, J.; Zarin, W.; Strifler, L.; Ghassemi, M.; Ivory, J.; Perrier, L.; Hutton, B.; Moher, D.; Straus, S.E. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, V.J.; Stevens, A.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Kamel, C.; Garritty, C. Paper 2: Performing rapid reviews. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Kelly, S.; Moher, D.; Clifford, T.J. Quality of conduct and reporting in rapid reviews: An exploration of compliance with PRISMA and AMSTAR guidelines. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Khatri, P.; Duggal, H.K. Frameworks for developing impactful systematic literature reviews and theory building: What, Why and How? J. Decis. Syst. 2023, 32, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affairs, U.N.D.o.E.a.S. United Nations E-Government Survey 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210019446 (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Basu, S. Cybercrime Insurance is Making the Ransomware Problem Worse. 2022. Available online: https://theconversation.com/cybercrime-insurance-is-making-the-ransomware-problem-worse-189842 (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- van der Vegt, G.S.; Essens, P.; Wahlström, M.; George, G. Managing Risk and Resilience. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, A.J.; Mahmood, S.M.J. Strategic Management Practices in the Public Sector: A literature review–Descriptive. Int. J. Adv. Multidiscip. Res. 2021, 9, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassa, Y.W.; James, J.I.; Belay, E.G. Cybercrime Intention Recognition: A Systematic Literature Review. Information 2024, 15, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah-Ofori, A.; Opoku-Boateng, F.A. Mitigating cybercrimes in an evolving organizational landscape. Contin. Amp. Resil. Rev. 2023, 5, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, T.J. Regulating Cybercrime through Law Enforcement and Industry Mechanisms. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2018, 679, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enigbokan, O.K.; Ajayi, N. Managing Cybercrimes Through the Implementation of Security Measures. J. Inf. Warf. 2017, 16, 112–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tøndel, I.A.; Line, M.B.; Jaatun, M.G. Information security incident management: Current practice as reported in the literature. Comput. Secur. 2014, 45, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Gupta, M. Information Security Management Practices: Case Studies from India. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2017, 20, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Jayakar, K. A socio-technical analysis of China’s cybersecurity policy: Towards delivering trusted e-government services. Telecommun. Policy 2018, 42, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Kar, A.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kizgin, H. Prevention of cybercrimes in smart cities of India: From a citizen’s perspective. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 1153–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.S.; Islam, U. Cybercrime: An emerging threat to the banking sector of Pakistan. J. Financ. Crime 2019, 26, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Bagchi, K.K.; Kirs, P.J.; Shukla, G.K. Cyber Risk Assessment and Mitigation (CRAM) Framework Using Logit and Probit Models for Cyber Insurance. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 997–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topa, I.; Karyda, M. From theory to practice: Guidelines for enhancing information security management. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2019, 27, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eboibi, F.E.; Richards, N.U. Electronic taxation and cybercrimes in Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa: Lessons from Europe and the United States of America. Commonw. Law Bull. 2019, 45, 716–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.H.; Lee, J. Policymakers’ perspective about e-Government success using AHP approach: Policy implications towards entrenching Good Governance in Pakistan. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2019, 13, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, M.; Chatterjee, D. Calculated risk? A cybersecurity evaluation tool for SMEs. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesch, R.; Pfaff, M.; Krcmar, H. A comprehensive model of information security factors for decision-makers. Comput. Secur. 2020, 92, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatji, M.; Marnewick, A.; von Solms, S. Validation of a socio-technical management process for optimising cybersecurity practices. Comput. Secur. 2020, 95, 101846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politanskyi, V.; Lukianov, D.; Ponomarova, H.; Gyliaka, O. Information Security in E-Government: Legal Aspects. Cuest. Politicas 2021, 39, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, B.; Sebastian, M.P. Examining the relationship between e-government development, nation’s cyber-security commitment, business usage and economic prosperity: A cross-country analysis. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2021, 29, 737–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Alowaidi, M.A.; Sharma, S.K. Impact of security standards and policies on the credibility of e-government. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2021, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A.; Clemente, S.; Nonino, F.; Palombi, G. Effectiveness and Adoption of NIST Managerial Practices for Cyber Resilience in Italy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mugarura, N.; Ssali, E. Intricacies of anti-money laundering and cyber-crimes regulation in a fluid global system. J. Money Laund. Control. 2021, 24, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalafi, N.; Veeraraghavan, P. Self-sufficiencies in Cyber Technologies: A requirement study on Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2022, 22, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ma’Aitah, M.A. Investigating the drivers of cybersecurity enhancement in public organizations: The case of Jordan. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 88, e12223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadidi, I.; Nweiran, A.; Hilal, G. The influence of Cybercrime and legal awareness on the behavior of university of Jordan students. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbowale, O.E.; Klingelhöfer, H.E.; Zerihun, M.F. Analytical hierarchy processes and Pareto analysis for mitigating cybercrime in the financial sector. J. Financ. Crime 2021, 29, 984–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwary, I. Evaluating Legal Frameworks for Cybercrime in Indonesian Public Administration: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2023, 17, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Alshamsi, S.K. Determinants of Cyberattack Prevention in UAE Financial Organizations: Assessing the Mediating Role of Cybersecurity Leadership. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadam, N.; Anjum, N.; Alam, A.; Mirza, Q.A.; Assam, M.; Ismail, E.A.; Abonazel, M.R. How to punish cyber criminals: A study to investigate the target and consequence based punishments for malware attacks in UK, USA, China, Ethiopia & Pakistan. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugari, I.; Kunambura, M.; Obioha, E.E.; Gopo, N.R. Trends, impacts and responses to cybercrime in the Zimbabwean retail sector. Safer Communities 2023, 22, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Chua, Y.T. The Role of Cybersecurity Knowledge and Awareness in Cybersecurity Intention and Behavior in the United States. Crime Delinq. 2024, 70, 2250–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.; Chadhar, M.; Firmin, S. Countermeasure Strategies to Address Cybersecurity Challenges Amidst Major Crises in the Higher Education and Research Sector: An Organisational Learning Perspective. Information 2024, 15, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbowale, O.E.; Klingelhöfer, H.E.; Zerihun, M.F.; Mashigo, P. Development of a policy and regulatory framework for mitigating cyberfraud in the South African banking industry. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakari, Y.; Amponsah, A.A. Amponsah, Economic cybercrime in the diaspora: Case of Ghanaian nationals in the USA. J. Money Laund. Control. 2024, 27, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, F.; Connolly, R. The great theory hunt: Does e-government really have a problem? Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leukfeldt, E.R. Phishing for suitable targets in the Netherlands: Routine activity theory and phishing victimization. Cyberpsychology, Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.; Leukfeldt, R. Phishing and malware attacks on online banking customers in the Netherlands: A qualitative analysis of factors leading to victimization. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 2016, 10, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Leukfeldt, E.R.; Yar, M. Applying routine activity theory to cybercrime: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Deviant Behav. 2016, 37, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.; Triplett, R. Capable guardians in the digital environment: The role of digital literacy in reducing phishing victimization. Deviant Behav. 2017, 38, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir, N.; Lawless, C.J. Exploring the human factor in cyber-enabled and cyber-dependent crime victimisation: A lifestyle routine activities approach. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 1665–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi-Tehrani, A.K.; Pontell, H.N. Phishing evolves: Analyzing the enduring cybercrime. Vict. Offenders 2021, 16, 316–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, L. Predicting online target hardening behaviors: An extension of routine activity theory for privacy-enhancing technologies and techniques. Deviant Behav. 2021, 42, 1532–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Gan, C.L.; Liew, T.W. Phishing victimization among Malaysian young adults: Cyber routine activities theory and attitude in information sharing online. J. Adult Prot. 2022, 24, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L. Guardians upon high: An application of routine activities theory to online identity theft in europe at the country and individual level. Br. J. Criminol. 2015, 56, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, J.E. Examining routine activity theory: A review of two books. Justice Q. 1995, 12, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, J.E.; Clarke, R.V. Situational Crime Prevention: Theory, Practice and Evidence. In Handbook on Crime and Deviance; Krohn, M., Hendrix, N., Penly Hall, G., Lizotte, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 355–376. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Gupta, M.; Rao, H.R. Insider threats in a financial institution. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansoori, A.; Al-Emran, M.; Shaalan, K. Exploring the Frontiers of Cybersecurity Behavior: A Systematic Review of Studies and Theories. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, N.S.; Von Solms, R.; Furnell, S. Information security policy compliance model in organizations. Comput. Secur. 2016, 56, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, N.S.; Maple, C.; Furnell, S.; Azad, M.A.; Perera, C.; Dabbagh, M.; Sookhak, M. Deterrence and prevention-based model to mitigate information security insider threats in organisations. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 97, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, G.D.; Siponen, M.; Pahnila, S. Toward a unified model of information security policy compliance. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.; Chi, Y.; Chao, L.R.; Tang, J. An integrated system theory of information security management. Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2003, 11, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, S.; Brendel, B. A Meta-Analysis of Deterrence Theory in Information Security Policy Compliance Research. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 1265–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, T.J. Understanding the state of criminological scholarship on cybercrimes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, D.W.; Welke, R.J. Coping with systems risk: Security planning models for management decision making. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohrke, F.T.; Frownfelter-Lohrke, C. Cybersecurity research from a management perspective: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. J. Gen. Manag. 2023, 48, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theories or Models | Context | Source |

|---|---|---|

| UTAUT Model | Smart Cities | [32] |

| Anti-Money Laundry Model | Global Regulatory System | [45] |

| Fraud Management Life Cycle | Banking Sector | [56] |

| Protection Motivation Theory | Banking Sector | [51] |

| Deterrence Theory | Laws in Global Context | [52] |

| Routine Activity Theory | General Population, Developing World | [53,54] |

| Learning Loop Framework | Higher Education | [55] |

| Risk Management Theories | Reviewers Collaboration | [34] |

| Socio-Technical Analysis | E-Government Public Value | [31] |

| NIST Cybersecurity Framework | Public Sector Cyber Resilience | [44] |

| Human-Organisation-Technology (HOT) Framework | Public Sector Organisations | [47] |

| Institutional Theory | Public Sector Organisations | [47] |

| Critical Success Factor | E-Government Sector | [37] |

| Socio-Technical STS Theory | E-Government Services | [40] |

| Gaps | Details | Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Sector-Specific Fragmentation | More attention towards monetary institutions than e-government services at large. | Interest in adapting behavioural models to the diverse needs of e-government services management throughout the landscape, not just financial institutions. |

| Regulatory and Policy Integration | Limited utilisation of cybersecurity models for governance. | Improve resilience in public sector digital services using international cybersecurity frameworks. |

| High Tech for High Ends | The technological recommendations do assist but are not affordable by third-world countries [21]. | Limited resources in adoption of state-of-the-art technology hinder public sector resilience to cybercrimes in third-world countries. |

| Managerial Integration for Cybercrime Prevention | Lack of managerial perspective in cybercrime mitigation within e-government services due to privacy and security concerns. | Involvement of managers in recommending prevention techniques within e-government services research. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mushtaq, S.; Shah, M. Critical Factors and Practices in Mitigating Cybercrimes within E-Government Services: A Rapid Review on Optimising Public Service Management. Information 2024, 15, 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15100619

Mushtaq S, Shah M. Critical Factors and Practices in Mitigating Cybercrimes within E-Government Services: A Rapid Review on Optimising Public Service Management. Information. 2024; 15(10):619. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15100619

Chicago/Turabian StyleMushtaq, Shahrukh, and Mahmood Shah. 2024. "Critical Factors and Practices in Mitigating Cybercrimes within E-Government Services: A Rapid Review on Optimising Public Service Management" Information 15, no. 10: 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15100619

APA StyleMushtaq, S., & Shah, M. (2024). Critical Factors and Practices in Mitigating Cybercrimes within E-Government Services: A Rapid Review on Optimising Public Service Management. Information, 15(10), 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15100619