A Proposed Translation of an Altai Mountain Inscription Presumed to Be from the 7th Century BC

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

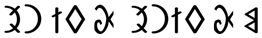

3.1. A Reexamination of the Old Hungarian Signs

is likely mirrored to make the combination with the

is likely mirrored to make the combination with the  sign easier and to save more space. The ligature is read as na.

sign easier and to save more space. The ligature is read as na.

is clearly visible. In addition, there are two parallel lines that belong to the head of one of the engraved deers. These lines do not belong to the Old Hungarian inscription and should be ignored. Unfortunately, Sartkožauly considered these lines part of the inscription and obtained an Old Hungarian

is clearly visible. In addition, there are two parallel lines that belong to the head of one of the engraved deers. These lines do not belong to the Old Hungarian inscription and should be ignored. Unfortunately, Sartkožauly considered these lines part of the inscription and obtained an Old Hungarian  sign in this place.

sign in this place.

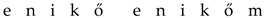

and ő sign

and ő sign  . Together they can be read as kő.

. Together they can be read as kő.3.2. Transliteration and Translation of the Altai Inscription

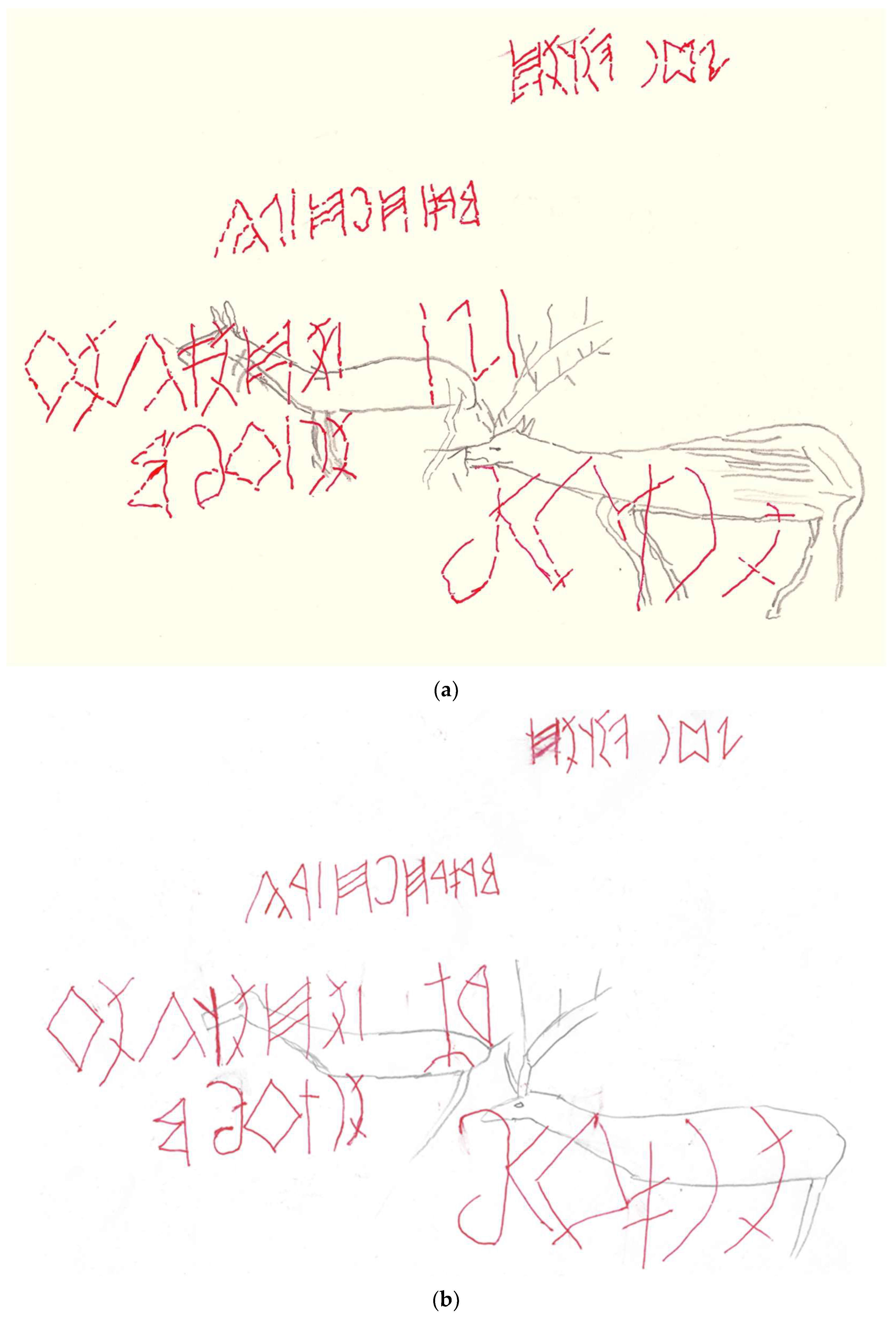

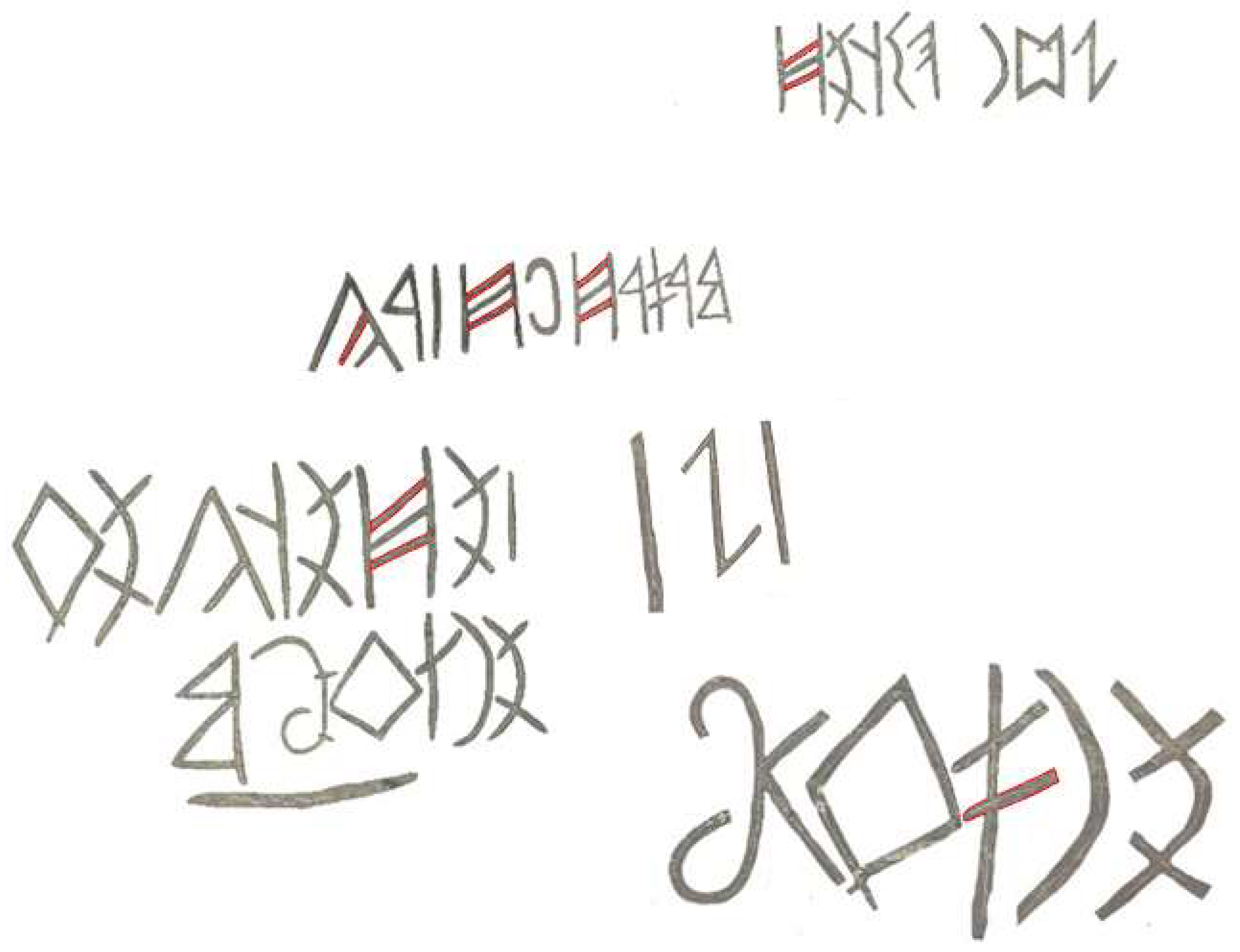

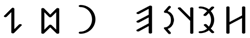

- The first row of the inscription starts with the name Kun Peter. Interestingly, the family name Kun is written first, and the given name Peter is written second. This order agrees with the Hungarian word order. In addition, Peter is a common given name in Hungary, and Kun, meaning ‘Cuman’, is also a common family name. In fact, Hungarian Kunság is the name of a region of Hungary that was settled by Cumans in the 13th century. Many people in that region consider themselves to be descendants of the Cumans and took Kun as a family name in later centuries.

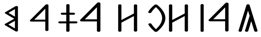

- The second row of the inscription contains the Hungarian word Magyarország, which means ‘Hungary.’ The Hungarians’ neighbors apparently confused the Hungarians with the Huns and the Onogurs, who occupied present day Hungary before the Magyars and allied peoples arrived in the 9th century. For example, German speakers in Austria and Germany call the country Ungarn.

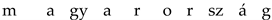

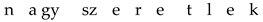

- The third row of the inscription contains the Hungarian word nagy, which means ‘big’ or ‘much’, and the Hungarian word szeretlek, which means ‘I love you.’ Hence the two words together express the sentence ‘I much love you.’

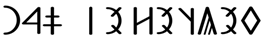

- The fourth row of the inscription contains the Hungarian word Enikő, which is a common woman’s name, and its conjugation Enikőm, where the -m suffix is a first-person possessive marker. Hence the meaning of Enikő, Enikőm is ‘Enikő, my Enikő’. The name Enikő is said to derive from Hungarian enéh meaning ‘young hind (female deer)’ [4]. It is perhaps for this reason that we see two deers drawn next to these words in the inscription.

4. The Inscription’s Implications for the Development of the Old Hungarian Script

5. An Alternative Translation of the Inscription

- Line 1: kunpétez

- Line 2: magy sz zcz sz

- Line 3: sz ksz sz eze gügek

- Line 4: enü ? o en sz kom

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sartkožauly, K. Complete Atlas of the Orkhon Monuments; Almaty Samga Press: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2019; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia, Old Hungarian Script. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OldHungarianscript (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Benkő, E.; Sándor, K.; Vásáry, I. A Székely Írás Emlékei; Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont: Budapest, Hungary, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia, Enikő. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enikő (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Revesz, P.Z. Establishing the West-Ugric language family with Minoan, Hattic and Hungarian by a decipherment of Linear A. WSEAS Trans. Inf. Sci. Appli. 2017, 14, 306–335. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, G. Magyar Hieroglif Írás; Írástörténeti Kutatóintézet: Budapest, Hungary, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Revesz, P.Z. Minoan archaeogenetic data mining reveals Danube Basin and western Black Sea littoral origin. Int. J. Biol. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 13, 108–120. [Google Scholar]

- Revesz, P.Z. Data mining autosomal archaeogenetic data to determine Minoan origins. In Proceedings of the 25th International Database Engineering and Applications Symposium, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–16 July 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revesz, P.Z. Art motif similarity measure analysis: Fertile Crescent, Old European, Scythian and Hungarian elements in Minoan culture. WSEAS Trans. Math. 2019, 18, 264–287. [Google Scholar]

- Maracskó, A. Hungarian Orientalism and the Zichy Expeditions. Master’s Thesis, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zaicz, G. (Ed.) Etimológiai Szótár: A Magyar Szavak és Toldalékok Eredete; Tinta Press: Budapest, Hungary, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Row | Script | Inscription |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Altai, right-to-left |  |

| Old Hungarian, left-to-right |  | |

| Latin |  | |

| 2 | Altai, right-to-left |  |

| Old Hungarian, left-to-right |  | |

| Latin |  | |

| 3 | Altai, right-to-left |  |

| Old Hungarian, left-to-right |  | |

| Latin |  | |

| 4 | Altai, right-to-left |  |

| Old Hungarian, left-to-right |  | |

| Latin |  |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Revesz, P.Z.; Varga, G. A Proposed Translation of an Altai Mountain Inscription Presumed to Be from the 7th Century BC. Information 2022, 13, 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13050243

Revesz PZ, Varga G. A Proposed Translation of an Altai Mountain Inscription Presumed to Be from the 7th Century BC. Information. 2022; 13(5):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13050243

Chicago/Turabian StyleRevesz, Peter Z., and Géza Varga. 2022. "A Proposed Translation of an Altai Mountain Inscription Presumed to Be from the 7th Century BC" Information 13, no. 5: 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13050243

APA StyleRevesz, P. Z., & Varga, G. (2022). A Proposed Translation of an Altai Mountain Inscription Presumed to Be from the 7th Century BC. Information, 13(5), 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13050243