Abstract

The process of identifying and managing Information and Communication Technology (ICT) risks has become a concern and a challenge for public and private organizations. In this context, risk management methodologies within the Brazilian Federal Public Administration organizations have become indispensable to help the managers of these organizations in decision making, especially in the distribution of public funds, elaboration of public policies focused on transparency, social actions contemplating indemnities, and social benefits, among others. In addition, the various ICT projects controlled by the public administration need a methodology to perform their management of ICT resources. In this article, we present the Governance and Risk Management methodology used to model the Administrative Council for Economic Defense (CADE) macro processes. The proposed methodology used the risk management process aligned to the ISO 31000 standards. This alignment was necessary for mapping CADE’s risk events, regardless of their complexity. The modeled ICT risk processes will support the organization’s managers in decision making and may be used or customized by any other organization of the Brazilian Federal Public Administration.

1. Introduction

Risk management is a fundamental activity for a public or private organization to be managed at all levels. It is an essential part of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Governance [1,2]. In addition, it contributes to the maturity of organizational management systems. Due to this relationship with all organization levels, risk management is associated with all organizational activities, and interaction with stakeholders is fundamental.

For the risk management process execution, it is essential to understand its iterative nature. This characteristic is relevant to the maturity of the process since its purpose is continuous improvement and monitoring, among the contributions of the risk management process. In addition, it is important to mention that performing risk management correctly allows organizations to consistently establish their strategy, paving the way for achieving organizational objectives and assisting stakeholders in making decisions. The scope of the risk management process is to carry out coordinated activities to direct and control the organization in risk-related matters [1].

Soares Netto et al. [3] stated that the concern with risks is a key aspect, as it ensures that organizational strategic objectives are less exposed to risks due to ICT failures. Because of this, the risks related to ICT problems are being considered increasingly relevant and present in managers’ agendas, since the impact that this type of risk can bring to the business has serious consequences since organizations are increasingly having their end activities dependent on the ICT area.

The lack of a methodology to perform risk management can be disastrous for public organizations and cause some consequences that can affect the citizens’ lives directly or indirectly, decreasing the credibility of the services offered to the population [4]. Chagas [5] analyzed the risks related to the economic area of a public administration organization and identified the importance of a methodology to manage risks due to the economic instabilities and the uncertainties inherent to the context of these organizations. In addition, efficient risk management in public organizations helps in the fight against corruption [6].

The General Law of Data Protection (LGPD) [7,8,9] and its respective punishments in case of non-compliance, keeping people’s data secure has become a current concern and, consequently, has become a point to consider when designing a risk management model, since there is the possibility that such information can be leaked or used illegally by third parties.

In public organizations, some methodologies address risk management with the primary purpose of mitigating possible fraud. For example, Miranda [10] highlighted the Manual of Integrity Management, Risks and Internal Controls of the Ministry of Planning, Development, and Management (MP), a methodology consisting of five steps aimed at meeting the demands of the MP. Another highlight is the Risk Management Manual of the Federal Audit Court (TCU) [11], whose objective is not only limited to managing risks but expands to possible opportunities.

This work is an expansion of the paper published in the ICEIS 2021 conference (23th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems) [9]. It presents the evolution of the modeling of the processes of Risk Management and Governance of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) based on the ISO 31000 [1]. The modeled processes can be customized and used by other Public Administration organizations and can support ICT managers in decision making, especially in the identification, analysis, evaluation, and mitigation of ICT risks.

The main goal of this paper is to apply the models proposed in the ISO 31.000 [1] in risk management in a Brazilian federal public administration agency by mapping the organization’s risk processes. Thus, we define the following hypothesis: Is it possible to apply of the ISO 31000 guidelines in the risk management solutions in public organizations? In order to map the processes, we conducted a literature review to identify existing studies in this context and held several meetings with the agency’s stakeholders to validate the identified risks and perform their classification, frequency, and impact. By identifying the risks, the organization will be able to define action plans to respond to the possible events, avoiding, mitigating, accepting, or even sharing the risks with the stakeholders. The survey of risk events will provide the organization with a more profound knowledge of the scenario in which it operates, whose record will be an input for decision making regarding the organization’s vulnerabilities and strengths, as well as the threats and opportunities that are part of the context of the federal public administration.

2. Background and Related Works

Public administration organizations carry out various types of activities, which are related to the provision of health services, social security, infrastructure development, research financing, regulation, taxes, among others [12]. The activities provided by these organizations involve a certain degree of risk, which may involve, but are not limited to, fraud, deficiency in service provision, waste, inefficiency, and loss of opportunity [12].

Risk management under the Federal Executive Branch in Brazil is governed by Complementary Normative Instruction (CNI) Nº 1, of 10 May 2016 [13]. The regulation provides that the bodies and entities of the Federal Executive Branch must adopt measures to systematize practices related to risk management, internal controls, and governance. The measures related to risk management that are determined in the CNI are related to implementing, maintaining, monitoring, and reviewing the risk management process, checking compatibility with the organization’s mission and strategic objectives, following the guidelines of the normative [13].

Brazilian government decision-making is subject to strong, and growing expectations of transparency and public accountability [14]. This need for transparency involves complex issues related to how the federal public administration’s risk management can be conducted in order to avoid possible threats to the organization [15]. It is also important to highlight a particularity of risks in the private sector, which differs from the public sector, regarding the confidentiality of decisions concerning risks. In the public sector, there is a requirement for accountability, which makes decisions public and transparent. In the private sector, these decisions are usually confidential, taking into account strategic business issues [15].

In private sectors, Sedinić and Perušić [16] mentioned the perspective of companies dealing with complex applications (such as banking, mining, or airport sectors). For the authors, early identification, analysis (including correlation and aggregation if necessary), assessment, and monitoring of risks allow them to develop an action plan whose decisions are made in such a way that these risks do not affect their business. It is also important to mention that there is a growing concern with financial statements in this kind of application, especially when sent to external audits.

Another interpretation of risk management in private organizations involves Industry 4.0, focused on the automation of its processes due to the Internet of Things (IoT). Brocal et al. [17] highlighted the practicality of risk management systems, classifying four hierarchical types of risks, these being: (a) risk governance, which involves the decision making of these risks respecting their processes and their organizations; (b) risk management, related to the use of methodologies and frameworks to provide the development team with a detailed analysis of their risks and their consequences; (c) risks related to occupational health and safety, concerning the people who develop means to manage the risks and their working conditions, and; (d) emerging risk management, which refers to the risks embedded in new technologies.

Risk management can be carried out at different administrative levels, being totally independent of the type in which the organization is inserted—be it public or private. In this context, several works were published in relation to risk management with a focus on different solutions. El-kiki et al. [18] presented the mGovernment framework to control and manage risks in government services, so that the framework could help in forecasting the benefits, in addition to calculating the risks resulting from any changes that are necessary for the context of administration governmental. After the proposal of the framework by the authors, other research was carried out with the objective of better understanding the mGovernment through the perspective of its users, so that the effectiveness of the framework could be measured [19] and also, its day-to-day use of the organization to minimize the impacts caused by the challenges of risk management [20].

Silva et al. [21] conducted with several Brazilian government agencies, the application of the Adaptation of Failure Mode and Effect Analysis (FMEA) to the Information Technology Solution Contracting Planning process as a tool to carry out risk management. The results made it possible for the agencies to review the procedures of the ICT contracting process so that improvements could be implemented. In addition, it allowed the agencies to customize the FMEA to suit the reality of each organization. Some works were published with the purpose of analyzing and understanding how risk management is carried out in different countries. Oulasvirta and Anttiroiko [22] analyzed the risk management carried out by the government of Finland. The results showed that even though the era of ICT is in evidence, the adoption of risk management in the country is still slow in municipal administrations (whether in large or small cities). Nadikattu [23] investigated the critical areas of ICT Governance in the United States private sector, pointing out the management components and the role of each component to mitigate the risk associated with it.

Junior [24] analyzed the challenges of implementing risk management in a Brazilian state government in terms of the impact of this type of management. For this, the author conducted a round of 13 interviews and observed the behavior of each participant. The results showed that, although risk management serves to legitimize the expansion of the organization’s internal control, the participants’ understanding was limited by at least three issues: (i) barriers in the auditors’ professional identity; (ii) the low relevance of internal controls; and (iii) the difficulty of disclosure of strategic risks. Finally, Elamir [25] sought to better understand the needs, benefits and approaches to risk management focused on the health area, making a comparison between traditional and business risk management approaches. In addition, the author presented a methodology called bow tie to assess the risk prospects proposed by the American Society for Health Risk Management.

Following the trend of Distributed Software Development (DDS) [26], and its advantages for organizations, Filippetto et al. [27] aimed to improve the quality of projects developed by organizations through Átropos. This model aims to manage the risks that may occur during the software life cycle. The authors conducted a case study in a software development company. The model consists of inputs (which initiates the application based on some database), risk identification (where the identification of activities, their ramifications, and impact assessment of such risks occurs). The management problem is the risk signaling by bots that monitor the project and the context model (capable of storing the history of events with their risks so that such information can be consulted for future projects). In their ramifications, the authors use the Risk Analytical Framework (RAF) for correct risk identification.

Kim [28] studied the effects of Effective Risk Management (RM) and its relationship with managers in South Korea’s food industry based on three aspects: (a) individual characteristics, (b) meta-structure variables, and (c) organizational variables. RM consists of systematic development platforms that identify and report each diagnosed risk to the development team. Other concepts used by the author is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), focused on the rational study of managers concerning proactivity and their ability to prevent risks and react when necessary, and; the Institutional Theory, which investigates the decision making made by managers and its impact on the company.

A significant concern for highly complex companies, Sedinic and Perusic [16] studied the usage of Information Security Risk Management methodologies. It works in harmony with each company’s overall risk management, using as an example three methodologies based on ISO 27001 [29] that have been adopted by a telecommunication company operating in Croatia and other European countries. The methodologies are: (a) Information Security Management System (ISMS), a process that consists of five steps and provides the identification and management of risk, classifying it into four categories (very low, low, medium, and high); (b) Basic Security Assessment (BSA), which comprises a list containing 20 risks (including location, file integrity, data production, and manipulation, among others), and is used only at system initiation and; (c) IT Security Risk Management, a process that consists of five steps and that is adopted to assess some specific security risks of the Information Technology area, establishing as threats the factors related to confidentiality and data integrity, as well as the availability of this information (that can be leaked or sent by mistake), is categorized as low, medium or high risk, depending on its probability and impact on the operation.

Júnior and Filho [30] detailed the Risk Management Implementation Project, introduced by the Government of the Federal District (GDF) in 2019. In cooperation with the Office of the Comptroller General of the Federal District (CGDF), whose project started in 2015—with the main purpose of improving public management and its risks through good communication with the agencies, providing the identification and classification of risks according to their complexities and allowing managers to make a decision consistent with their reality. A risk management system focused on the public sector is essential for fraud prevention, correct allocation of funds, and reduction of superfluous expenses.

Gallis and Alves [31] investigated the risks pertinent to the financial area. The authors based themselves on the Banking Supervisory Council of Basel—created by the G-10 in 1974, on the concept of Operational Risk (encompassing issues such as human failure, system, process, and external factors) and Banking Risk (which involves risks pertinent to interest rates, credit, and stock market shares). In this area, identifying risk from its history and the issuing of probabilities is essential for the investor to be aware of the financial asset available and its variables, which external changes or market trends can influence.

Miranda [10] proposed a methodology for risk management in the Ministry of Planning, Development, and Management (MP), based on cycles and with the following steps: (a) Survey of the Environment; (b) Identification, investigating the history of risks and their consequences; (c) Assessment of these risks, establishing their degrees of complexity and corresponding probabilities; (d) Risk Response, involving planning to address this risk, and; (e) Information, Communication, and Monitoring, responsible for reporting the risk management situation and conducting evaluations.

Tshabalala and Khoza [32] studied the concept of Effective Conflict Risk Management (ECM) aimed at the agile development market, which consists of managing a project’s risks continuously and flexibly to changes, in order to provide fast release delivery. The authors conducted a qualitative survey with 179 people working in the ICT field to verify its effectiveness.

The Secretariat of Planning, Governance, and Management (SEPLAN) [11] of the Federal Court of Accounts (TCU) presented the details about the Risk Management Program to improve risk management, especially in court decisions. The TCU’s Risk Management Manual consists of a document containing the information related to risks to be understood concisely and transparently. The proposed process consists of eight steps: (a) Establishing the Context; (b) Risk Identification; (c) Risk Analysis; (d) Risk Assessment; (e) Risk Treatment; (f) Communication and Consultation with Stakeholders; (g) Monitoring, and; (h) Continuous Improvement.

Ávila [33] studied the importance of risk management methodologies for municipal governments in Brazil regarding fraud prevention and transparency, based on the protocols adopted in the government of Canada. Based on the generic risk management process proposed by Hill and Dinsdale [34]—that is, risk identification, impact assessment, decision making, and monitoring—the author emphasized issues to be discussed in municipal governments about the strengths and weaknesses of management, going through the knowledge analysis of their employees, establishing objectives and managing these risks.

Junior [24] conducted an analysis based on accountability in-state public institutions in order to investigate the pertinent risks, their management by managers, and the impacts they may cause on society. The authors considered a survey conducted by internal state auditors, and this study aimed to implement a risk management system to provide greater internal control of public administration through thirteen interviews. The results found problems related to lack of interest in risk management (such as high demand from state agencies and change of teams) and lack of leadership. These problems can hinder public transparency.

Okonofua and Rahman [35] studied the factors that contribute to proper risk management and proposed the creation of the Risk Management Plan (RMP), a technique to engage people, process, and technology in a process so that organizations follow a detailed document that contains all phases of a project—i.e., elicitation, analysis, development, testing, and remediation—and provide a controlled and monitored RMP. RMP consists of three steps: (a) Management Support; (b) Risk Management Development; (c) Success Criteria; and (d) Ongoing Monitoring and Analysis.

Brocal et al. [17] studied the impacts and risks that the Internet of Things brings about in Industry 4.0 in its relationships between man, machine, and robot. In their research, the authors proposed methodologies based on Complex Systems Governance (CSG) that builds on the three characteristics of IoT—RFID identification, sensing, and actuation—along with risk management systems in organizations and human performance analytics (such as strength and logical reasoning).

Aiming at better risk management in the hiring of services focused on ICT in public organizations, Silva et al. [21] proposed an adaptation to the Failure Mode and Effect Analysis (FMEA) within the Information Technology Solution Hiring Planning (PCSTI). Based on laws and ordinances enacted in the state and federal spheres, the authors’ proposed adjustment to FMEA consists of five steps: planning, general risk study, analysis to define its complexity, interpretation of data and results, and monitoring, which were approved by five public entities through interviews and brainstorming, established in the methodology’s process.

Okonofua et al. [36] investigated the existing gaps in the literature on risks involved in the Information Security (IS) area for leadership decisions and their influence on risk management in this segment. For the authors, the use of the Full Range Leadership Theory (FRLT) proposed by Bass and Avolio [37], provides through the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) nine properties for three types of leadership: transactional, transformational, and passive-preventive, which are effective for risk management.

3. Methodology

The objective of this work is to present the stages of the risk management process of the ICT processes of the General Coordination of Information and Communication Technology (CGTI) of the Administrative Council for Economic Defense (CADE). The organization has its methodology for risk management, prepared according to ISO IEC 31000 [1] and the set of rules and regulations published by the Federal Public Administration (APF), among them: (1) Joint Normative Instruction number 01/2016 [13] which provides for internal controls, risk management, and governance within the Federal Executive Branch; (2) decree number 9023 of 22 November 2017 [38] which provides on the governance policy of the federal public administration; (3) CADE ordinance number 283, of 11 May 2018 [39] which approves the Governance Policy, Integrity Management, Risks, and Management Controls within the scope of the Administrative Council for Economic Defense.

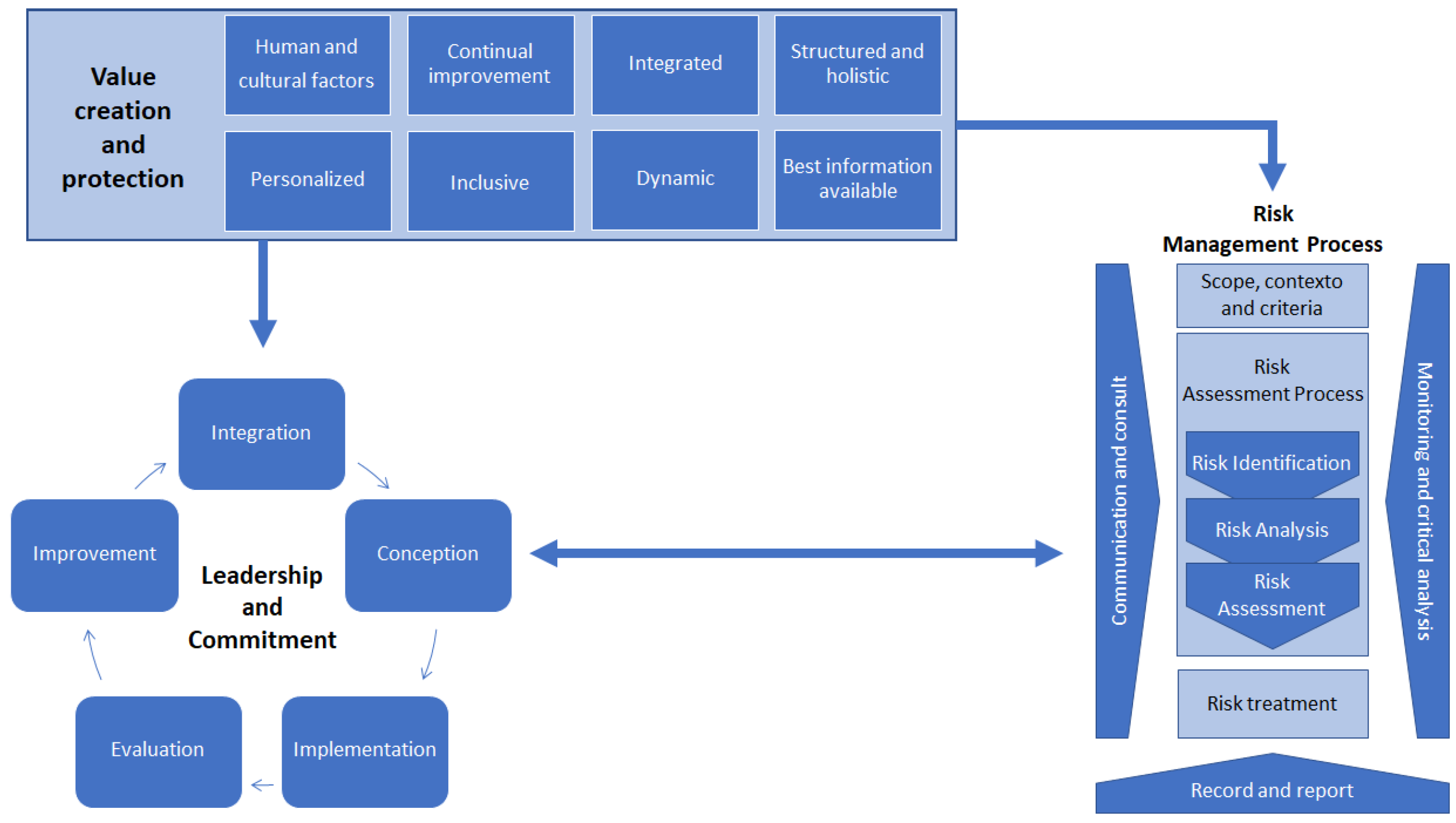

According to the 31010 [40] standard, the assessment process is the part of risk management that provides a structured process to identify how the objectives may be affected; also, according to the standard, the process tries to answer the following fundamental questions: (1) what may happen and why?; (2) what are the consequences?; (3) what is the probability of its future occurrence?; (4) are there factors that mitigate the consequence or reduce the risk probability?; and (5) is the risk level tolerable or acceptable, and does it require additional treatment? To gather the necessary information for the mapping of risk events in CGTI’s processes, we adopted the risk management process based on the 31000 [1] standard. The components of the standard are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Elements of the Risk Management Process [1].

According to ABNT NBR ISO/IEC 31000 [1], risk identification has the purpose of finding, recognizing, and describing risks that may help or hinder an organization from achieving its objectives. Risk identification involves identifying risk events, their causes, and consequences. In this phase of the work, we consider the typologies defined in CADE’s methodology, which we can classify as 1. Operational risks: Events that can compromise the body or entity’s activities, usually associated with failures, deficiency, or inadequacy of internal processes, people, infrastructure, and systems; 2. Body image/reputation risks: Events that can compromise society’s trust (or that of partners, clients, or suppliers) about the body or entity’s capacity to fulfill its institutional mission; 3. Legal risks: Events derived from legislative or regulatory changes that may compromise the activities of the organ or entity; 4. Financial/budgetary risks: Events that may compromise the capacity of the organ or entity to count on the budgetary and financial resources necessary to carry out its activities, or, still, events that may compromise the budget execution itself, such as delays in the bidding schedule; 5. Integrity risks: Risks that configure actions or omissions that may favor the occurrence of frauds or acts of corruption.

In the risk assessment phase, which aims to support decisions, risks are assessed based on the probability that they will occur and on the impact they may have on the organization’s objectives. Probability should be measured by analyzing the causes of the risk event, observing aspects such as observed or expected frequency. Categorized by weights and in descending order, the parameters for the definition according to the probability analysis are 5. Very high probability: with an occurrence above 90%, and expected, repetitive and constant event; 4. High probability: with an occurrence between 50% and 90%, an event can occur in a usual way; 3. Medium probability: contemplating occurrences between 30 percent and 50 percent establishes a prediction of when an event can occur but is expected; 2. Low probability: with a possibility of incidence between 10 percent and 30 percent, refers to an event with characteristics similar to the previous one, with the difference that in this weight, the event is unexpected; 1. Very low probability: representing possibilities below 10 percent refers to an extraordinary event.

The impacts are the effects of the occurrence of a risk event and are measured from the analysis of the effects. These events can be described in five categories in descending order, according to their weight: 5. Catastrophic: classified as weight 5, this risk event impacts the objectives irreversibly; 4. Robust: with weight 4, it impacts the objectives whose reversal becomes difficult; 3. Moderate: the risk event negatively impacts the objective but can be recoverable; 2. Weak: the effects influence the established objectives in a negligible manner, and; 1. Insignificant: the impact on the objectives is minimal.

Considering the risk level is the product of probability X impact. Thus, the risk level is expressed by combining the probability of occurrence of a risk event and its impacts on the organization’s objectives. Following this relation and considering the established weights, the methodology adopted by CADE classifies the impacts according to their complexity, defining in a low to extreme risk level, in which the incidence of an event with a pre-established probability of occurrence may have insignificant or disastrous consequences. Once the level of risk is known, it is necessary to establish strategies to treat the risks. Risk treatment involves the identification of options to treat these risks, evaluating these options, and selecting the most appropriate alternatives to modify the risk level (Risk Response). CADE, in the adoption of its methodology, establishes the following risk responses: 1. Low risk: it is understood that the risk level is within tolerance, being considered the acceptance of this occurrence; 2. Medium risk: A response divided between acceptance and reduction indicates that the risk level is close to but not within the established tolerance; 3. High risk: defined with the response of reducing, transfer, and avoid, it is an indication that the risk level is outside the established tolerance and needs to be reduced to acceptable levels; 4. Extreme risk: following the three risk responses proposed in the previous item, the actions in this category aim at reducing the impact immediately, even if it is difficult to reduce it to an acceptable level.

Organization Context

The CGTI is one of the portfolios that make up the Directorate of Administration and Planning (DAP) of CADE. Through the Information Technology Master Plan (PDTI), established between the years 2017 and 2020, the CGTI defined in its Strategic ICT Objectives its mission, vision, and values, which are: (1) Improve the management of users and employees; (2) Implement information systems; (3) Provide its employees with a robust infrastructure; (4) Ensure Information and Communication Security; (5) Foster management and governance, and; (6) Improve the provision of services to society.

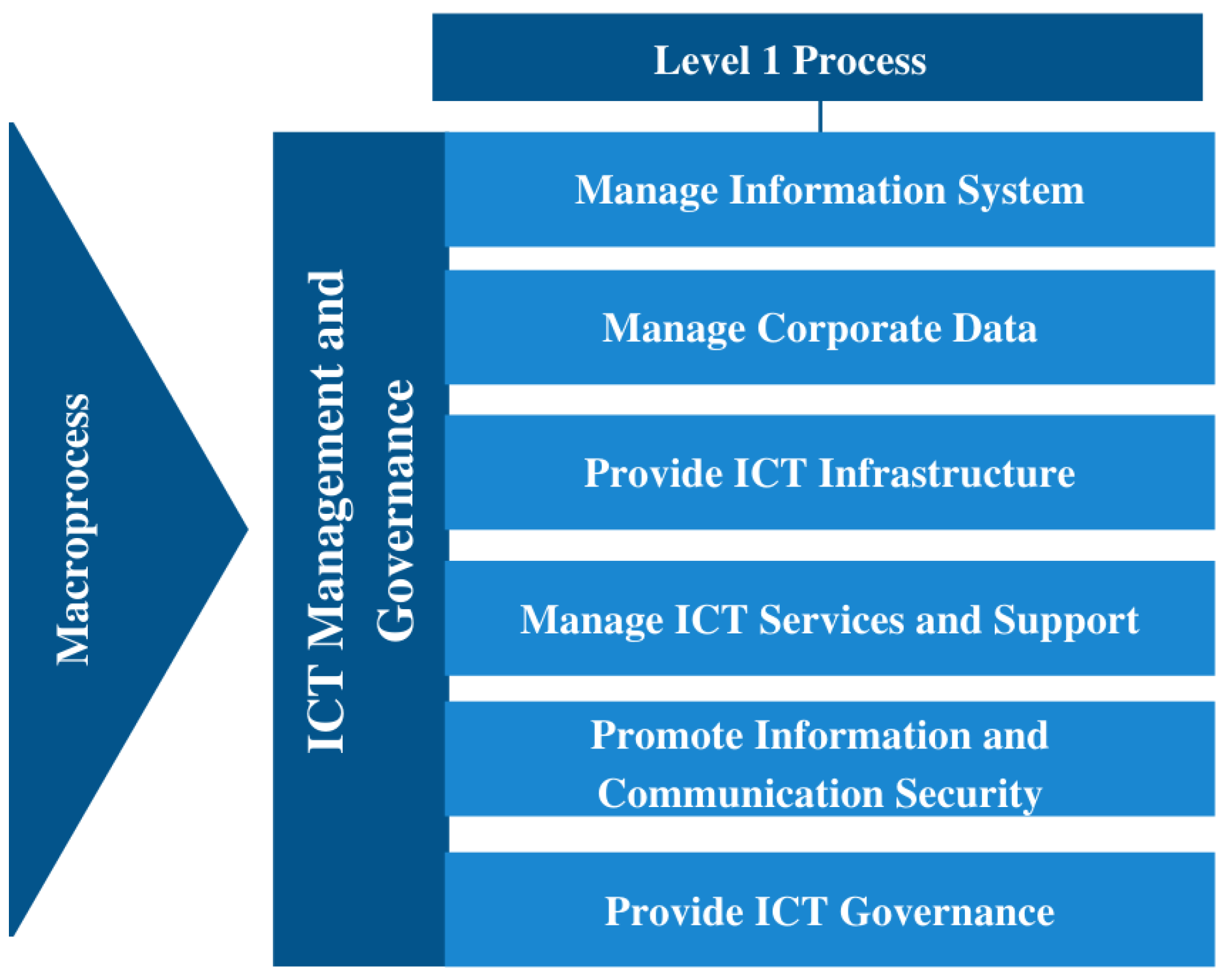

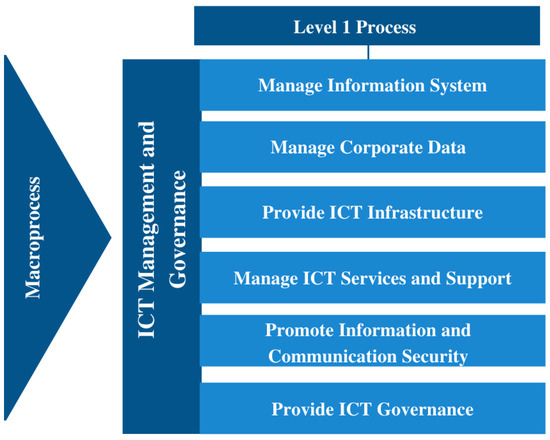

Aggregated in the ICT Management and Governance Macroprocess, are the CGTI level I processes, defined based on CADE’s value chain, as shown in Figure 2, from which risk events will be identified taking into account specific regulations and legislation.

Figure 2.

Level 1 process [41].

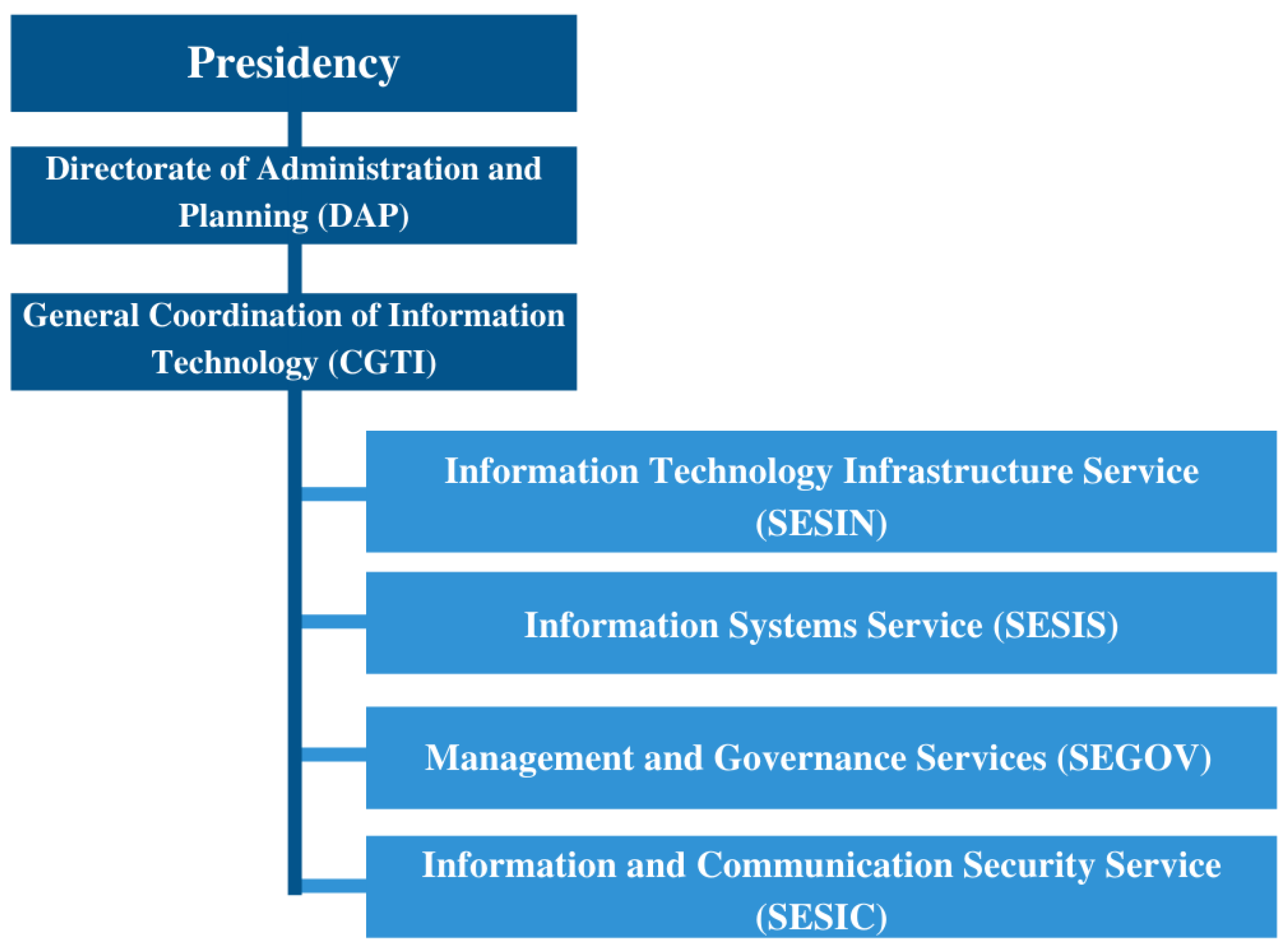

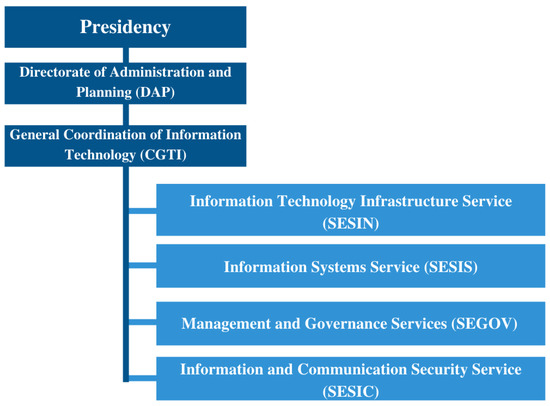

In order to execute these processes and achieve strategic objectives, CGTI’s structure is divided into organizational units: Information Technology Infrastructure Service (SESIN); Information Systems Service (SESIS); Management and Governance Services (SEGOV); and Information and Communication Security Service (SESIC), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structure of the General Coordination of Information and Communication Technology (CGTI) [42].

4. Results

4.1. Provide ICT Governance

According to the ISO/IEC 38500 [43], ICT governance is the system by which the current and future use of ICT is directed and controlled within the organization. Within CADE, the SEGOV (Figure 3) has as one of its attributions to manage the risks related to ICT governance. The attributions/responsibilities of the SEGOV are: 1. to plan, coordinate, and guide the actions of acquisition and contract management related to management and governance; 2. to manage projects related to ICT management and governance; 3. To implement and sustain management and governance solutions; 4. to identify, evaluate and propose technology solutions to support CADE’s last activities; 5. to propose policies and guidelines concerning the planning, implementation, and maintenance of activities related to information and communication technology governance; 6. to formulate and maintain an information and communication technology governance and management model.

In its PDTI, CGTI also listed its ICT needs regarding the strategic objective of Promoting ICT Management and Governance, which were considered in the phase of establishing the context for risk identification, which are: (1) Implement and formalize the processes of ICT Risk Management, ICT Business Continuity, ICT Contracting and Contract Management for ICT Goods and Services, ICT Governance, ICT Portfolio, and Project Management, and ICT Service Management; (2) Knowledge management project; (3) Standardization of the Artifacts of Contracting ICT Services and Goods Acquisitions and; (4) Implementation of the data integration and quality solution. In a case study carried out at CADE by Canedo et al. [42], after applying a questionnaire to the CGTI members/servers, the authors identified among the processes not defined and not implemented, the ICT Service Continuity, ICT Project Management and ICT Service Management processes. In addition, the authors identified the absence of some artifacts related to ICT processes that were already implemented at CADE.

Thus, based on the strategic objectives of PDTI, the ICT needs, and the duties of SEGOV, identifying risks in the process of Providing ICT Governance began. In this initial phase, the Brainstorming technique was used with the CGTI team. Five events were listed, which are: 1. flaws in the implementation of the Risk Management process at CGTI: of operational typology, these problems are caused by flaws related to the team’s knowledge about risks, prioritization of the risk management process, and implementations of the Agir system, its effects reflect in the exposure of risks that can affect the business, in the non-fulfillment of compliance rules and the accountability, fitting as internal control the use of ordinances and norms regarding risk management at CADE; 2. Non-formalization of the project management methodology: of an operational nature, it relates the events linked to projects and has as its causes the non-prioritization on the part of experienced members, the lack of knowledge of some members, and the low adherence to concepts directed towards project management, resulting in delays in the stipulated deadlines, lack of details in the results and standardization problems; 3. Failures in the management of human resources of ICT: with operational typology, these events occur due to lack related to corporate systems for people management, the adaptation of new employees, procedures for performance evaluation, and interaction of leaders on related topics, causing a high turnover of servers, difficulty in the viability of processes and drop in performance of employees, fitting as internal control the use of norms directed to people management; 4. Non-implementation of knowledge management: also of an operational nature, generated by the low knowledge management culture and lack of process definition, resulting in loss of organizational knowledge and discontinuity; 5. Failure in delivering value from CGTI to the business: of strategic nature, it is caused by failures related to the strategic alignment between business and ICT, communication of the ICT area with CADE’s senior management and governance structures, it leads to delivery problems, budget execution, affects the achievement of the organization’s goals and waste of time in non-relevant initiatives, whose internal control provides for the use of governance norms.

Once the risk events related to the process of Providing ICT Governance were identified by the CGTI team, the risk assessment process defined by the ISO 31000 [1] follows to the next step, risk analysis, which aims to understand the nature and characteristics of the identified risks. Having as a reference the criteria established by the CADE methodology, as presented in Section 3, the CGTI team analyzed the identified risk events defining the probability of occurrence, and the impact of such events in the accomplishment of the ICT objectives related to the process under analysis, the Table 1 presents this information, as well as the answers to the risks also defined by the team.

Table 1.

Risk Assessment of the Provide ICT Governance process.

After selecting the answers to the risks, the next step is the creation of new internal controls or revision and improvement of already existing controls, regarding the risk events of the process to Provide ICT Governance, the CGTI defined actions to be implemented, as follows (1) Training activities; (2) Implementation of risk management according to CADE’s methodology; (3) Analyze alternatives for the AGIR System; (4) Publish and adopt Project Management methodologies/good practices; (5) Implementation of Pg. CADE; (6) Publicize the new employees’ adaptation process; (7) CGTI’s participation in the General Data Plan; (8) Encourage the use of project management tools, such as Wiki, Redmine, and GitHub; (9) Map CGTI’s business processes and; (10) Formalize CGTI’s Communication Plan. These actions are the responsibility of the CGTI coordinator and the other CGTI leaders and will be implemented by December 2021.

Completing this step provides the agency with the necessary inputs so that managers can continue to critically analyze and monitor the risks of the organization’s Providing ICT Governance process.

4.2. Provide ICT Infrastructure

Among the level I processes of CGTI is the process of Providing Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Infrastructure, whose sector responsible is the SESIN; the sector has the following attributions/responsibilities: 1. plan, coordinate and guide the actions of acquisition and contract management related to infrastructure; 2. Managing projects related to ICT infrastructure; 3. Implementing and sustaining communication and connectivity solutions; 4. Managing risks related to ICT management and governance; 5. Identifying, evaluating, and proposing technology solutions to support CADE’s last activities; 6. Coordinate the sustaining of information technology and communication assets; 7. assist users in operating information technology and communication assets; 8. maintain the operability of CADE’s safe room.

The risk events defined by the CGTI team, their causes, effects, and typology, as well as the internal controls already in place related to the Provision of ICT Infrastructure process, are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Risk events identified in the Provide ICT Infrastructure process.

Once the risk events were identified for the Providing ICT Infrastructure process, the CGTI team performed the risk assessment, defining the probability and the impact of these events on its activities and goals, according to Table 3.

Table 3.

Risk Assessment of the Provide ICT Infrastructure process.

After selecting the answers to the risks, the next step is the creation of new internal controls or review and improvement of existing controls; regarding the risk events of the Provision of ICT Infrastructure process, the CGTI defined actions to be implemented, as follows (1) Create a process/manual for raising technical requirements; (2) Participation of the infrastructure team since the beginning of the process/project; (3) Create a communications plan; (4) Update the ordinance No. 406. These actions are the responsibility of the entire CGTI and, more specifically of SESIN, and aim to be implemented by December 2021.

With the completion of this stage, the institution has inputs to proceed with the critical analysis and monitoring of the risks of Providing CADE’s ICT Infrastructure.

4.3. Manage Information System and Manage Corporate Data

According to CADE’s Information and Communication Technology Master Plan 2017/2020, CGTI is the unit responsible for the management of information and communication technology resources, having SESIS as its subordinate area, as presented in the Figure 3, SESIS’ attributions are: 1. planning, implementing and making available solutions based on information systems to meet business needs; 2. promoting the development of corporate information systems based on the Electronic Government Interoperability Standards and e-gov accessibility; 3. Coordinating the activities related to the systems architecture management; 4. Supervising the systems development processes for the information technology and communication projects; 5. Performing the acquisitions related to the information systems portfolio of CADE’s Information Technology and Communication Master Plan; 6. Managing projects related to the information systems portfolio of CADE’s Information Technology and Communication Master Plan; 7. Continuity, support of third-party platforms; 8. Data management and governance.

The last two attributions (7 and 8) are not formalized in the Internal Rules of the Organ since the managers added them at the time of the interview for this work. However, since SESIS is responsible for the two-level 1 processes presented in Figure 2, being them (1) Manage Information System and (2) Manage Corporate Data, Table 4 and Table 5 present the identification of the risk events of the respective processes.

Table 4.

Identified Risk Events in the Manage Information System process.

Table 5.

Identified Risk Events in the Corporate Data Management process.

Once the risk events were identified for the processes under the responsibility of the SESIS unit, the CGTI team performed the risk assessment, defining the probability and impact of these events on its activities and objectives, according to the Table 6 and Table 7, respectively.

Table 6.

Risk Assessment of the Manage Information System process.

Table 7.

Risk Assessment of the Manage Corporate Data process.

After selecting the responses to the risks, the next step is the creation of new internal controls or revision and improvement of existing ones: (1) Training regarding the structure and quality of the specification of demands; (2) Establish project importance criteria and make the business area aware of the adherence to the established criteria; (3) Strengthening the business areas and software factory regarding the importance of specification alignment and validation; (4) New tender; (5) Establish mechanisms to validate the use of the methodology; (6) Guarantee a prioritized agenda for training; (7) Acquisition of a new solution to support project and portfolio management; (8) Creation of scenarios/studies about the long-term viability of the project; (9) Establish preventive criteria to avoid the acquisition of a platform with insufficient documentation and outside the market standards. These actions are the responsibility of the entire CGTI and, more specifically, the SESIS unit and aim to be implemented by December 2022, considering that item 4 also requires the participation of the General Coordination of People Management, the CGESP.

Regarding the process of Managing Corporate Data, the actions defined for implementation were: (1) Structure of a data governance service and (2) Qualification of professionals to work with data governance. These actions are the responsibility of the entire CGTI and, more specifically, of the SEGOV and SESIS units and have the goal to be fully implemented by December 2022, considering that item 2 is on an ongoing basis. With the completion of this stage, CGTI has inputs to proceed with the critical analysis and risk monitoring of the processes Information System Management and Corporate Data Management continuously and cyclically, in accordance with ISO/IEC 31000 [1].

The CGTI unit responsible for Managing ICT Services and Support is the SEGOV. To assist the team in identifying the risk events of these processes, we use the ICT Service Catalog (CSTIC), a document whose goal is to structure the information about the services offered and their tasks, to guide customers and users of the services, which are: 1. internet access; 2. network access; 3. Monitoring of sessions/meetings; 4. antivirus; 5. data storage; 6. update the IT environment; 7. data backup; 8. database; 9. closed-circuit TV; 10. service center; 11. electronic mail; 12. systems development; 13. firewall; 14. corporate printing; 15. network infrastructure; 16. Network Server; 17. Storage; 18. Portal support; 19. Systems support; 20. Software support; 21. Hardware support; 22. Corporate Telephony.

The risk events defined by the CGTI team, their causes, effects, and typology, as well as the existing internal controls related to the Manage ICT Services and Support process, are 1. Lack of service standardization: classified as an operational risk, this event is caused by lack of knowledge and a service script, causing standardization and rework problems, having as internal control the use of the GLPI Knowledge Base; 2. Missing a deadline to hire support: considered an operational risk, this risk event occurs through excess demand and lack of definition of the project’s scope, resulting in the discontinuity in the provision of support services and an increase in operational costs, with a planned flow of contract renewals and checkpoint meetings; 3. Centralization of knowledge in a few people: being an operational risk, this event, caused by the amount of personnel and lack of knowledge management process, results in the lack of a quick resolution of a problem and dependence on collaborators with specific skills to solve it, in which the internal control mentions the Demand Management System and the Password Vault System; 4. Poorly humanized customer service: considered an image risk, it is caused by lack of training and compliance to service protocols, generating a poor quality of service and harming the image of CGTI, impacting negatively on the User Satisfaction Index (INSI). Once the risk events have been identified, the CGTI team performed the risk assessment, defining the probability and the impact of these events on its activities and objectives, according to Table 8.

Table 8.

Risk Assessment of the Manage ICT Services and Support process.

To finalize the risk mapping of the Manage ICT Services and Support process, the CGTI team proposed new internal controls, assigning responsibilities and deadlines, in order to reduce the probability of occurrence of the identified risks, which are: 1. start monthly auditing if all calls have the associated knowledge bases, and if the knowledge bases are feasible (per sample); 2. Monthly monitoring of the hiring process in the control point meetings; 3. actions that promote the sharing of knowledge; 4. train the employee responsible for the relationship with outsources with the course “Disney Way to delight customers”; in which the responsibilities are of control inspectors, CGTI, the hiring planning team, and SEGOV, with deadlines set until December 2021. With the information generated, CGTI has inputs to perform the monitoring and critical analysis of all stages of risk management of the Manage ICT Services and Support process. According to ISO/IEC 31000, the purpose of monitoring is to ensure and continuously improve the quality and effectiveness of the process.

4.4. Promote Information and Communication Security

According to the ISO 27001 [29], organizations need to have an information security management system; its implementation is a strategic decision and aims to preserve the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information. At CADE, the Information and Communication Security Policy (POSIC) was defined, which structure is composed by the Information and Communication Security Committee (CSIC), by the CIS manager, and by the Network Incident Treatment and Response Team (ETIR). The CGTI has as one of its subordinated sectors the SESIC unit. Its attributions/responsibilities are (1) to plan, coordinate and guide the acquisition actions and contract management related to information and communication security; (2) to manage projects related to Information and Communication Security; (3) to implement and sustain information and communication security solutions; (4) to manage risks related to information and communication security; (5) to identify, evaluate and propose technology solutions to support CADE’s last activities; (6) to inform, guide and supervise the acquisition actions and contract management related to information and communication security. Furthermore, to inform, guide, and supervise CADE’s units to fulfill the information security norms applied to the information and communication technology; (7) To support the implementation of the information and communication security policy; (8) To perform actions related to ICT regarding the General Data Protection Law and the National Program of Sensitive Knowledge; (9) To promote disclosure campaigns and training, aiming to disseminate the Information and Communication Security Policy and the culture of information cybersecurity among internal and external users of information and communication technology resources.

The ISO/IEC 27005 [45] provides guidelines for the risk management process, specifically for information and communication security. The risk event identification step is performed by identifying the assets, threats, controls, vulnerabilities, and consequences to determine the events that may cause a potential loss to the organization. Among CGTI’s assets, we can categorize them in two sections: Primary Assets (PA) and Support and Infrastructure Assets (ASI). The AP consists of nine IDs corresponding to the information and communication security area, whose responsibility is exclusive to the head of SESIC, these being: (1) Management over acquisitions and correlative contracts; (2) Creation and management of projects; (3) Implementation of solutions; (4) Risk analysis; (5) Identification, evaluation and provide solutions in order to subsidize CADE’s finalist activities; (6) Inform CADE’s units about the measures taken and that affect the ICT sector; (7) Support to the implementation of policies aimed at this segment; (8) Adequacy of the internal ICT policies with the LGPD and the National Sensitive Knowledge Program; (9) Promote knowledge to internal and external users about the Information and Communication Security Policy in order to cultivate a culture of cyber security. On the other hand, ASI deals with CADE’s electronic equipment, physical and virtual spaces, which are the responsibility of the head of SESIN. These are (1) Technical Rooms; (2) Safe Room; (3) AWS Cloud (Amazon); (4) CADE’s Cloud; (5) Computers and Notebooks; (6) Servers’ Mobile Devices.

The team performed the identification of threats, which according to ISO/IEC 27005 [45] have the potential to compromise the assets, and therefore the organization. Threats can come from inside or outside the organization. The standard also highlights that a threat can affect more than one asset. The existing internal controls in CGTI were identified, such as the standards and processes already defined and the vulnerabilities. These, in turn, do not cause harm by themselves because there needs to be a corresponding threat to exploit it. Table 9 presents the identified items applied to the primary assets and the support and infrastructure assets.

Table 9.

Threats, Controls, and Vulnerabilities.

With the information described in Table 9, the CGTI team performed the identification of risk events related to SESIC assets and processes; we characterized the Risk Events with their causes, effects, and typology (image, legal, operational or reputational risk), according to the criteria established by CADE’s methodology. These are: (1) Non-implementation of the Continuity Management Process: of an operational nature, this event occurs due to the absence of human resources and failures in prioritizing the process, whose effects reflect in non-compliance with the recommendations of POSIC and the Information and Communication Technology Governance Policy (PGTIC), lack of a Project Continuity Policy, lack of a Management Plan—represented by the Disaster Recovery Plan (DRP) and the Operational Contingency Plan and reflects in the delay in response to incidents, for which the internal control proposes the use of POSIC/PGTIC and a defined Risk management Process; (2) Failure in the hiring of solutions and services: considered an operational risk, the event is caused by the lack of knowledge in the bidding process and of the solution to be contracted, which generates a misallocation of public resources and solutions that do not meet the needs, as internal control, provides for the application of standards related to hiring and contracting processes of ICT solutions; (3) Discontinuity of projects: being an operational risk, this event is motivated by the absence of human resources and a lack of project management methodology, which results in a compromising of the reach of CGTI’s objectives, for that CADE foresees in its internal control the use of Public Administration Norms—contemplating the Federal Comptroller General (CGU), the Federal Audit Court (TCU) and the Federal Attorney General (AGU)—and the use of Good Practice Manuals; (4) Incomplete/partial implementation of solutions: also of an operational nature, occurs due to the lack of knowledge of the solution (including the transmission of the same to the members of the portfolio) and the absence of human resources, generating expenditure of resources, compromise with the CGTI objectives and a greater possibility of compromising information security, which leads the internal control to analyze contractual specifications; (5) Inexistence of a formalized risk management process: considered an operational risk, this event occurs as a result of lack of knowledge, prioritization and absence of human resources, which compromises factors linked to information security; (6) Data leakage: considered a risk to CADE’s image and reputation, this event of serious nature is caused by faults related to the Risk Management Process not defined, knowledge in risk management and the absence of human resources with expertise in the information security area, which causes mainly data exposure (contemplating personal data, confidential information) and consequently compromises the body’s image, leading to the use of security solutions (firewall, antivirus) and norms; (7) Non-compliance with information security norms by the business areas: considered an operational risk, it is caused by the incompatibility of the solution with the CGTI structure and the lack of knowledge of security standards, resulting in vulnerability in the network and impossibility to implement a solution; (8) Unauthorized eavesdropping: being an image and reputation risk, it is caused by the lack of cameras in the technical rooms and the absence of access control, which result in an exposure of data and unauthorized copies, in which the internal control provides for the individual configuration of all virtual ports and the deactivation of unused ports; (9) Attempted improper access: Considered an operational risk, this event occurs due to failure in equipment configuration and update in security modules, which generates vulnerability in equipment, possibility of undue access—consequently having access to sensitive data—and privilege scale, being up to internal control the segregation of the network and the use of physical and logical access standards; (10) Lack of implementation of LGPD processes: of a legal nature, this event—whose causes are the same as in item (1)—generates a non-compliance with the Federal Government’s best practices guide and with the laws imposed in the LGPD.

Table 10 presents the assessment of the risk events identified by the team; by analyzing the probability and impact of the identified risk events, the team was able to assess the level of risk and then select how they will respond to the risk.

Table 10.

Risk Assessment of the Promote Information and Communication Security process.

After selecting the risk responses, the next step is to create new internal controls or review and improve existing ones: (1) implementation of the business continuity management process; (2) creation of a process/manual for collecting technical requirements; (3) hiring of specialized information security services; (4) formalization of the risk management process; (5) implementation of LGPD processes; (6) campaigns and user training to raise awareness; (7) definition of procedures and standards for periodic scans; (8) software and equipment update management policy; (9) implementation of vulnerability management procedures; and, (10) hiring of intrusion testing services. These actions are the responsibility of the entire CGTI and, more specifically, of the SESIC unit, with the head of SEGOV, all of which will be implemented by December 2022. With the completion of this stage, the CGTI has inputs to proceed with the critical analysis and monitoring of the risks of the process of Promoting Information and Communication Security in a continuous and cyclical manner.

4.5. Discussion

The quality of public services is the best indicator of the good functioning of the state and the government, these exercising their role through the federal public administration. Increasing the quality of services requires good coordination of public agencies at any level as well as increasing the performance of these entities. An increased degree of public service quality means increasing citizens’ trust in federal public administration. The implementation of risk management process requires special attention to detail being a large-scale process whose actions aim to streamline federal public administration. At the level of federal public administration, the implementation and/or use, depending on the stage at which the implementation process is, of the ISO 31.000 is monitored and supported. The ISO 31.000 is especially recommended because over the last decades it has been shown that ISO can be used in any type of public organization.

In this context, this work was motivated based on a need to generate new insights into ISO 31.000-based risk management. ISO 31.000 use is an essential technique for good risk management. After applying the ISO 31.000 guidelines on identification, classification, impact, level and risk response, it was possible to define the organization’s threats, controls and vulnerabilities. Furthermore, we found that the ISO 31.000 guidelines provide good guidance in identifying and analyzing risks. This study has some implications for research and practice. For research, our study can help researchers seeking to advance ISO 31.000-Based Risk Management. For instance, the results of this paper show the use of ISO 31.000 in the risk management. Thus, the reported information can guide researchers to identify gaps and develop new technological solutions to automate and minimize human effort in ISO 31.000-based risk management activities and the decision-making process. For practitioners, this study shows how public companies can use risk management with the ISO 31.000. Therefore, they can use it to understand the risk management use process and use the existing resources in the company to improve organizational learning in risk management. In addition, can use the results to support the decision-making process and support the professionals in managing risk by reusing knowledge and assisting in decision-making. This can make it easier to identify, analyze and evaluate risks in the company’s organizational process and help them to use ISO 31.000 in the company.

5. Threats to Validity

This research presents some threats that may affect the results. The first involves the communication gap among members of CADE’s ICT governance team, which leads to problems such as (1) raising irrelevant or superficial risks to the organization’s context; (2) ignoring potential risks due to lack of knowledge; and (3) lack of an in-depth validation of all risks identified during the process. With these risks identified, we held meetings with those responsible for CADE’s ICT governance to present and detail the identified risks and mitigate this threat.

Another threat is related to ICT processes that have not been mapped systemically by the ICT management and governance team. The lack of modeling of all processes can lead to a limited view of potential risks linked to its activities, which may negatively impact CADE’s risk management process. In order to mitigate this threat, CADE started modeling the ICT Governance processes that were not yet systematically modeled.

Regarding the external factors that may cause some threat to this study, we can mention that some team members do not have an adequate level of proficiency in the organization’s ICT Management and Governance processes, causing the imprecision of details and the possibility of failures. To mitigate this risk, we held meetings with managers to validate the risks identified and discuss employees’ perceptions about each risk.

Finally, Table 9—regarding the events of the Support and Infrastructure Assets—needs detailed information regarding the vulnerabilities that can occur through a failure, such as telecommunication problems, fire, and theft, the consequences of which can directly affect the administrative routines of the organization.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we conducted a study to investigate the issues related to risk management. The identified works were essential to develop the case study and define a methodology for CADE’s risk management. Furthermore, from the review, it was possible to identify the variables to be analyzed in the risk management process, from identifying to monitoring risks.

In our findings, it is possible to conclude that due to the cyclical nature of the risk management process, it is possible to apply different techniques in the same steps based on the ICT macro processes. Therefore, being in opposite situations, it is not necessary to define a specific technique for each step of the process but to define a set of techniques and tools at different times for the same step. Due to this, it is understood the importance of the context definition step contemplated in the methodology proposed by ISO 31000, which enables the organization to define a set of techniques that can assist in the other steps of the risk management process, besides allowing a risk management process design adapted to the organization’s context.

This also contributes to helping mitigate some threats encountered in the development of the work, since from a process design that includes a set of techniques for each step, the stakeholders will be provided with inputs that promote good communication between teams and tools adapted to survey and assess the relevant risks, resulting in a consistent result that reflects the reality of the organization. As future work, we propose to address the identified validation threats and will advance CADE’s employees’ understanding of the adequacy of their processes with the Brazilian General Data Protection Law.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.D.C. and A.P.M.d.V.; methodology, A.P.M.d.V. and R.M.G.; validation, A.d.V.S., F.L.L.M. and B.J.G.P.; formal analysis, B.J.G.P. and R.T.d.S.J.; investigation, E.D.C. and A.P.M.d.V.; resources, E.D.C., A.P.M.d.V., R.M.G. and A.d.V.S.; data curation, E.D.C., A.P.M.d.V., R.M.G. and A.d.V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.D.C., A.P.M.d.V., R.M.G., A.d.V.S. and B.J.G.P.; writing—review and editing, R.T.d.S.J. and F.L.L.M.; visualization, E.D.C. and R.T.d.S.J.; supervision, E.D.C., R.T.d.S.J., F.L.L.M.; project administration, E.D.C., R.T.d.S.J., F.L.L.M., V.E.d.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by CNPq—Brazilian National Research Council (Grants 312180/2019-5 and 465741/2014-2), in part by the Administrative Council for Economic Defense (Grant CADE 08700.000047/2019-14), in part by the General Attorney of the Union (Grant AGU 697.935/2019), in part by the National Auditing Department of the Brazilian Health System SUS (Grant DENASUS 23106.118410/2020-85), in part by the Brazilian Ministry of the Economy (Grant DIPLA 005/2016), and in part by the General Attorney’s Office for the National Treasure (Grant PGFN 23106.148934/2019-67).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ISO/IEC 31000:2018; Risk Management—Guidelines. ISO—International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/65694.html (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Santos, P.O.L.d.; Silva, A.P.B.d.; Souza, J.; de Sousa, R.T., Jr. Proposal to build a maturity model in ICT governance and management. REAd. Rev. Eletrônica Adm. (Porto Alegre) 2020, 26, 463–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netto, S.; Fernandes, A. Proposta de artefato de identificaç ao de riscos nas contrataç oes de TI da Administraç ao Pública Federal, sob a ótica da ABNT NBR ISO 31000: Gest ao de riscos. Univ. Brasília 2013. Available online: https://repositorio.unb.br/handle/10482/13252 (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Anderson, J.M. Government Risk Management Lags behind Vendor Practices. IT Prof. 2013, 15, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavas, J.P. Risk Analysis in Theory and Practice; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, B.S. Gest ao de riscos na Administraç ao Pública como instrumento de combate à corrupç ao. Univ. Fed. Santa Catarina 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/218918 (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Martins, A.D.F.; da Silva Barros, P.V.; Monteiro, J.M.; de Castro Machado, J. LGPD: A Formal Concept Analysis and its Evaluation. In Proceedings of the Anais do XXXV Simpósio Brasileiro de Bancos de Dados, SBBD 2020, Online, 28 September–1 October 2020; pp. 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferr ao, S.É.R.; Carvalho, A.P.; Canedo, E.D.; Mota, A.P.B.; Costa, P.H.T.; Cerqueira, A.J. Diagnostic of Data Processing by Brazilian Organizations—A Low Compliance Issue. Information 2021, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canedo, E.D.; do Vale, A.P.M.; Gravina, R.M.; Patr ao, R.L.; de Souza, L.C.; dos Reis, V.E.; de Mendonça, F.L.L.; de Sousa, R.T., Jr. An Applied Risk Identification Approach in the ICT Governance and Management Macroprocesses of a Brazilian Federal Government Agency. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS)-Volume 1, SCITEPRESS, Online, 26–28 April 2021; pp. 272–279. Available online: https://www.scitepress.org/Papers/2021/104759/104759.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Miranda, R.F.d.A. Implementando a gest ao de riscos no setor público. Belo Horiz. Fórum 2017, 1, 204. [Google Scholar]

- Tribunal de Contas da União. Manual de Gestão de Riscos do TCU. Available online: https://portal.tcu.gov.br/planejamento-governanca-e-gestao/gestao-de-riscos/manual-de-gestao-de-riscos/ (accessed on 15 August 2021).

- Rana, T.; Hoque, Z.; Jacobs, K. Public sector reform implications for performance measurement and risk management practice: Insights from Australia. Public Money Manag. 2019, 39, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instrução Normativa Conjunta Ministério da Economia, Controladoria-Geral da União n. 01, de 2016. Available online: https://repositorio.cgu.gov.br/handle/1/33947 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Vanalle, R.M.; Lucato, W.; Ganga, G.; Alves Filho, A. Risk management in the automotive supply chain: An exploratory study in Brazil. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, C.; Rothstein, H. Business Risk Management in Government: Pitfalls and Possibilities. SSRN Electron. J. 2000, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sedinic, I.; Perusic, T. Security Risk Management in complex organization. In Proceedings of the 38th International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics, MIPRO 2015, Opatija, Croatia, 25–29 May 2015; Biljanovic, P., Butkovic, Z., Skala, K., Mikac, B., Cicin-Sain, M., Sruk, V., Ribaric, S., Gros, S., Vrdoljak, B., Mauher, M., et al., Eds.; IEEE: Opatija, Croatia, 2015; pp. 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocal, F.; González, C.; Komljenovic, D.; Katina, P.F.; Sebastián, M.A. Emerging Risk Management in Industry 4.0: An Approach to Improve Organizational and Human Performance in the Complex Systems. Complexity 2019, 2019, 2089763:1–2089763:13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Kiki, T.; Lawrence, E.; Steele, R. A management framework for mobile government services. In Proceedings of the CollECTeR, Sydney, Australia, 13 July 2005; pp. 2009–2014. [Google Scholar]

- El-Kiki, T.; Lawrence, E. Mobile User Satisfaction & Usage Analysis Model of MGovernment Services. Verified OK. Consortium International. 2006. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10453/6900 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Kiki, T.E.; Lawrence, E. Government as a mobile enterprise: Real-time, ubiquitous government. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Information Technology: New Generations (ITNG’06), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 10–12 April 2006; pp. 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.A.d.; Oliveira, E.C.d.; Canedo, E.D. Avaliaç ao de Riscos do Processo de Planejamento da Contrataç ao de TI: Uma proposta para Órg aos Governamentais Brasileiros. Rev. Bras. Sist. Inf. Rio Jan. 2016, 9, 168–186. [Google Scholar]

- Oulasvirta, L.; Anttiroiko, A.V. Adoption of comprehensive risk management in local government. Local Gov. Stud. 2017, 43, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nadikattu, R.R. Risk Management in Private Sector. SSRN Electron. J. 2019, 22, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, V.H.K. Gest ao de riscos no setor público brasileiro: Uma nova lógica de accountability? Rev. Contab. Organ. 2020, 14, 163964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamir, H. Enterprise risk management and bow ties: Going beyond patient safety. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2019, 26, 770–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audy, J.L.N. Desenvolvimento Distribuído de Software; Elsevier: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Filippetto, A.S.; Lima, R.; Barbosa, J. Um Modelo de Gerenciamento de Riscos para Projetos de Software com Equipes Distribuídas. iSys-Braz. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 13, 114–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S. The role of knowledge and organizational support in explaining managers’ active risk management behavior. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2019, 32, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 27001:2013; Information Technology—Security Techniques—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. ISO—International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/54534.html (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- De Araújo Júnior, J.B.; de Pinho Filho, L.C. Implantaç ao da Gest ao de Riscos no Governo do Distrito Federal–GDF: Uma Iniciativa de Inovaç ao da Gest ao Pública. Rev. Processus Estud. Gest Jurídicos Financ. 2019, 10, 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gallis, M.P.; Alves, F.M. Operaç oes Bancárias: Riscos e incertezas Operacionais. Rev. Eletrônica Dep. Ciências Contábeis Dep. Atuária Métodos Quant. (REDECA) 2018, 5, 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tshabalala, M.M.; Khoza, L.T. Maximizing the Organization’s Technology Leverage through Effective Conflict Risk Management within Agile Teams. In Proceedings of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists, SAICSIT 2019, Skukuza, South Africa, 17–18 September 2019; de Villiers, C., Smuts, H., Eds.; ACM: Skukuza, South Africa, 2019; pp. 33:1–33:6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, M.D.G. Gest ao de riscos no setor público. Rev.-Controle-Doutrina Artig. 2014, 12, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.; Dinsdale, G. Uma base para o desenvolvimento de estratégias de aprendizagem para a gest ao de riscos no serviço público. Cad. ENAP 2003, 23, 80. Available online: http://repositorio.enap.gov.br/handle/1/692 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Okonofua, H.; Rahman, S. Evaluating the Risk Management Plan and Addressing Factors for Successes in Government Agencies. In Proceedings of the 17th IEEE International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications/12th IEEE International Conference on Big Data Science and Engineering, TrustCom/BigDataSE 2018, New York, NY, USA, 1–3 August 2018; pp. 1589–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonofua, H.; Rahman, S.; Ivanova, R. An Empirical Examination of the Effects of IT Leadership on Information Security Risk Management in USA Organizations. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Computers and Their Applications, CATA 2019, EPiC Series in Computing, Honolulu, HI, USA, 18–20 March 2019; Lee, G., Jin, Y., Eds.; 2019; Volume 58, pp. 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Antonakis, J.; Avolio, B.J.; Sivasubramaniam, N. Context and leadership: An examination of the nine-factor full-range leadership theory using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 261–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidência da República. Decreto Nº 9.203, de 22 de Novembro de 2017. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/decreto/d9203.htm (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Presidência da República. PORTARIA Nº 283, DE 11 DE MAIO DE 2018. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/web/guest/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/14551033/do1-2018-05-16-portaria-n-283-de-11-de-maio-de-2018-14551029 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- ISO/IEC 31010:2019; Risk Management—Risk Assessment Techniques. 2nd ed. Number ISO/IEC 31010:2019 in ISO/TC 262 Risk Management. ISO—International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–264.

- Conselho Administrativo de Defesa Econômica. Plano Diretor de Tecnologia da Informação e Comunicação (2021–2024). Available online: https://cdn.cade.gov.br/Portal/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/tecnologia-da-informacao/Plano%20Diretor%20de%20TIC%20do%20CADE%202021-2024%20-%20v1.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Canedo, E.D.; do Vale, A.P.M.; Patr ao, R.L.; de Souza, L.C.; Gravina, R.M.; dos Reis, V.E.; de Mendonça, F.L.L.; de Sousa, R.T., Jr. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Governance Processes: A Case Study. Information 2020, 11, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 38500:2018; Information Technology—Governance of IT for the Organization. ISO—International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/62816.html (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Presidência da República. Instrução Normativa n. 01, 05 de Abril de 2019. Available online: https://repositorio.cgu.gov.br/handle/1/63755 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- ISO/IEC 27005:2018; Information Technology—Security Techniques—Information Security Risk Management. ISO—International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/75281.html (accessed on 1 July 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).