The Relationship between Perceived Health Message Motivation and Social Cognitive Beliefs in Persuasive Health Communication

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Health Communication

2.2. Behavior Modeling

2.3. Social Cognitive Theory

2.4. Gender-Based Tailoring

3. Method

3.1. Research Objectives

- Ensure the message is clear.

- Ensure the message is credible, believable and realistic.

- Provide good evidence for costs (threats) and benefits for not doing and doing the target behavior, respectively.

- Ensure the message uses an appeal that is appropriate for the target audience.

- Ensure the messenger is seen as a credible source of the information.

- Ensure the message will not be offensive or harm the target audience.

- Ensure the behavior the target audience is asked to perform is reasonably easy.

- Ensure the message gets and maintains the attention of the target audience.

3.2. Research Questions

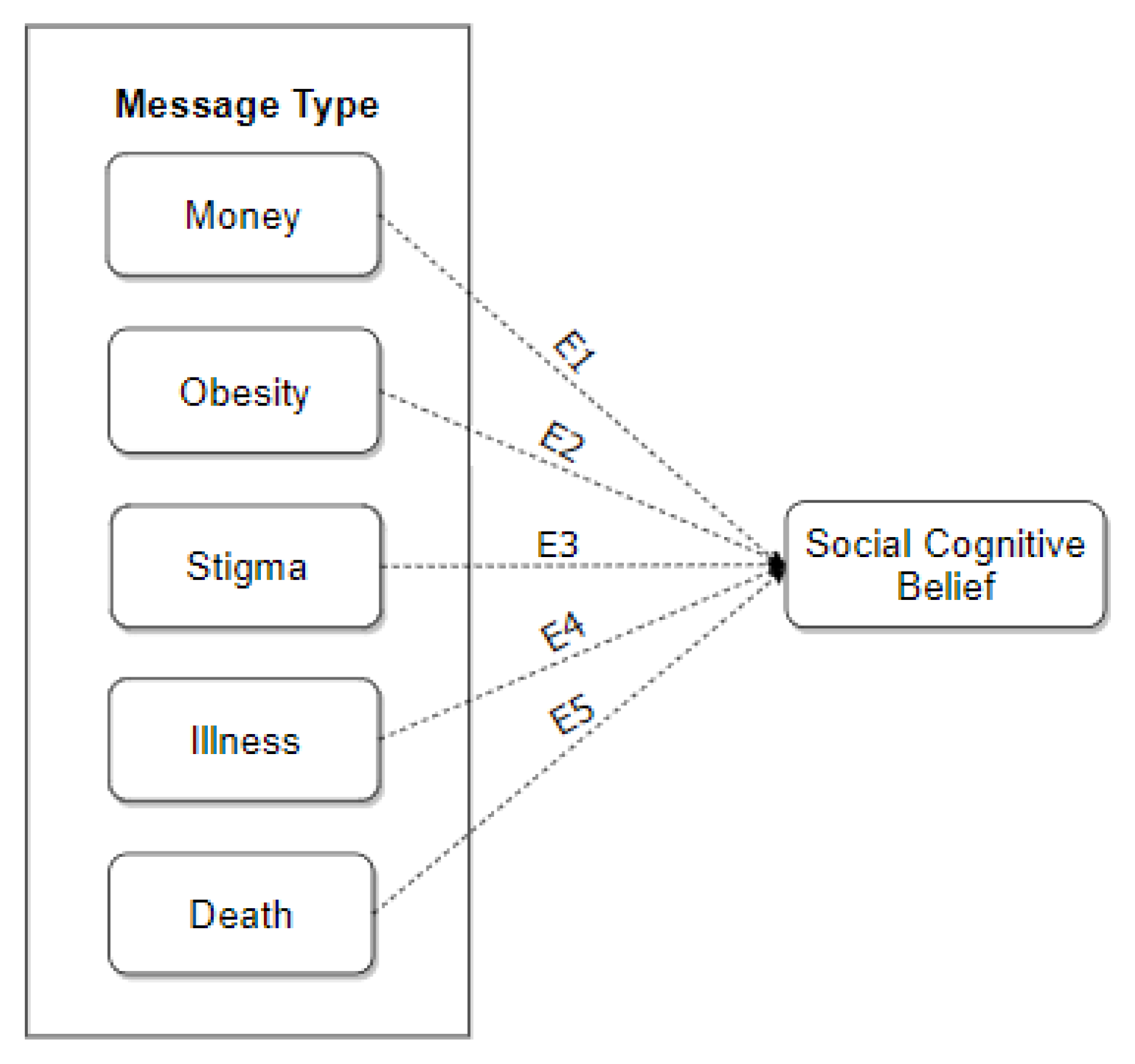

3.3. Exploratory Model

3.4. Participants

4. Results

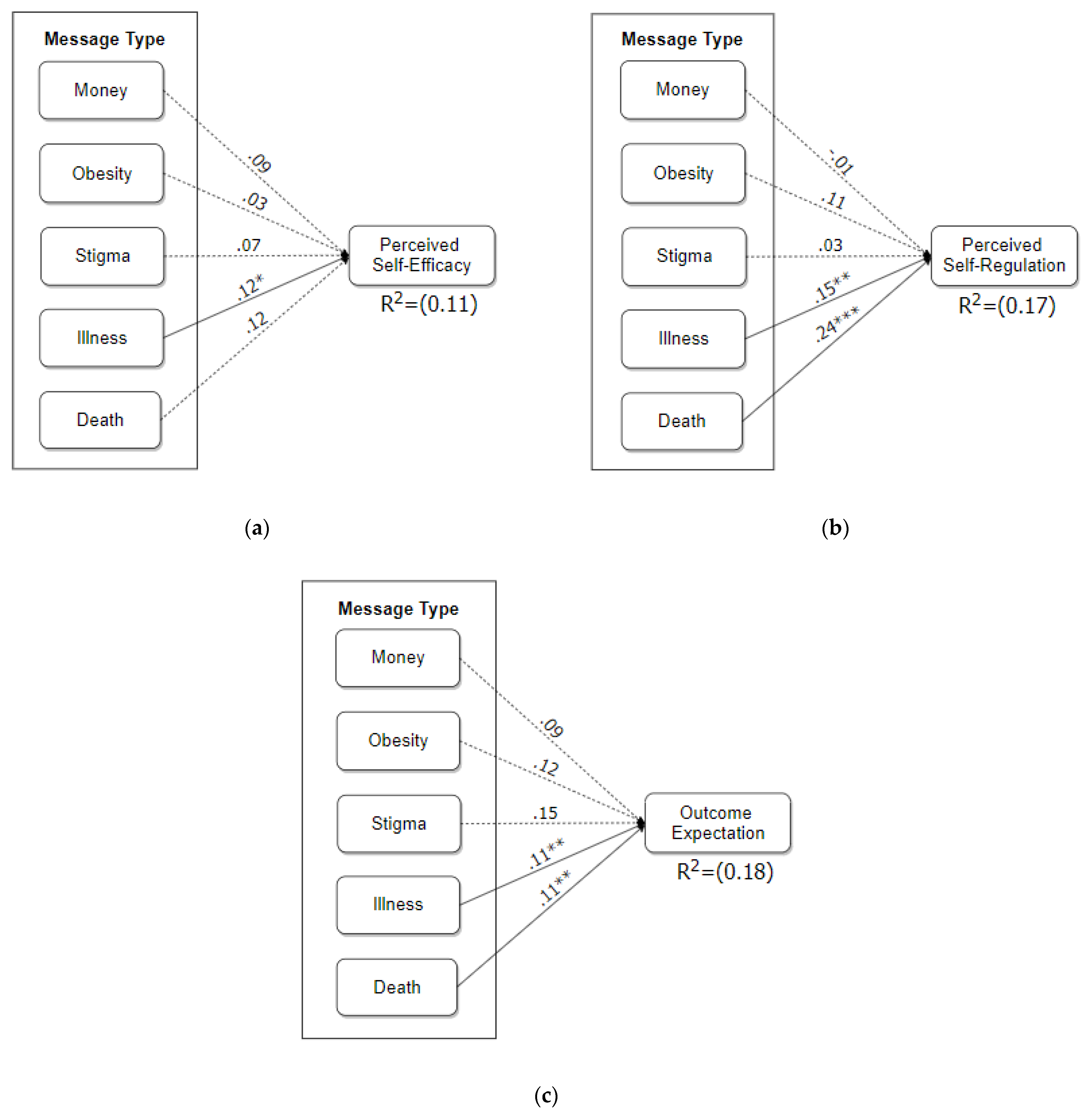

4.1. Path Modeling

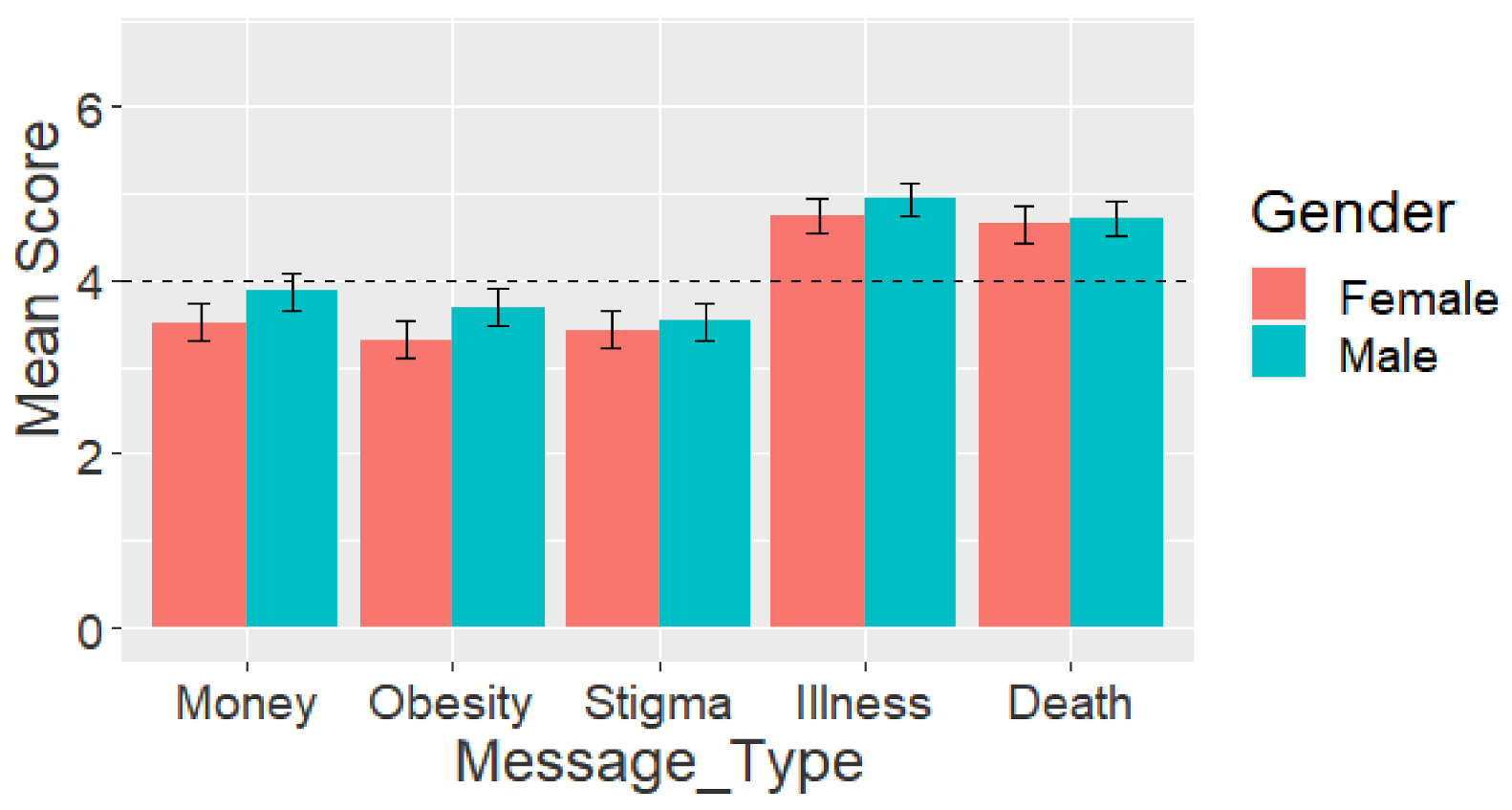

4.2. Analysis of Variance

5. Discussion

5.1. Relationship between Perceived Motivation of Health Messages and Social–Cognitive Beliefs

5.2. Perceived Motivation of Health Messages

5.3. Gender Differences in the Relationship between Perceived Motivation of Health Messages and Users’ Social–Cognitive Beliefs about Bodyweight Exercise

5.4. Differences in Levels of Perceived Motivation of Health Messages of Different Types

5.5. Summary and Implications of Main Findings in the Design of Persuasive Health Messages

- Users are motivated by illness- and death-related health messages, but not by financial cost-, obesity-, and social stigma-related messages.

- There is a significant relationship between the perceived motivation of illness- and death-related messages and users’ social–cognitive beliefs about exercise.

- The more users are motivated by illness- and/or death-related messages, the more likely they are to have high outcome expectations, believe in their ability to perform a health behavior, and regulate themselves towards achieving the health goals.

- Due to the above findings, Illness- and death-related messages may be used as a persuasive technique to motivate behavior change in persuasive health communication.

- Social stigma-based messages related to obesity are likely to be effective in influencing the social–cognitive beliefs of females, but not those of males.

5.6. Contributions

5.7. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Public Health Communications. A Public Health Intervention. Available online: https://professionals.wrha.mb.ca/old/extranet/publichealth/priorities-communication.php (accessed on 31 July 2021).

- Bandura, A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol. Health 1998, 13, 623–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, L.; Sheridan, S.; Lewis, M.; Boudewyns, V.; Melvin, K.L.; Kistler, C.; Lux, L.J.; Cullen, K.; Lohr, K.N. Communication and Dissemination Strategies to Facilitate the Use of Health-Related Evidence. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. 2013, 1–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Community Guide: Health Communication and Health Information Technology. Available online: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/health-communication-and-health-information-technology (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada. 2008; pp. 1–25. Available online: https://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/php-psp/ccph-cesp/pdfs/cc-manual-eng090407.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Wakefield, M.A.; Loken, B.; Hornik, R.C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 2010, 376, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rimal, R.N.; Lapinski, M.K. Why health communication is important in public health. Bull. World Health Organ. 2009, 87, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Ontario. Health Communication Message Review Criteria, 2nd ed.; Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012; Available online: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/H/2012/health-comm-review-crtieria.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Gallagher, K.M.; Updegraff, J.A. Health Message Framing Effects on Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior: A Meta-analytic Review. Ann. Behav. Med. 2012, 43, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, S. Book Review: mHealth: New Horizons for Health through Mobile Technologies: Based on the Findings of the Second Global Survey on eHealth (Global Observatory for eHealth Series, Volume 3). Health Inform. Res. 2012, 18, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.K.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Bernhardt, J.M. Mobile Text Messaging for Health: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gowin, M.; Cheney, M.K.; Gwin, S.H.; Wann, T.F. Health and Fitness App Use in College Students: A Qualitative Study. Am. J. Health Educ. 2015, 46, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murnane, E.L.; Huffaker, D.; Kossinets, G. Mobile health apps. In Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers (UbiComp ’15), Osaka, Japan, 9–11 September 2015; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 261–264. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.; Weber, I.; Cha, M.; Lee, C. Persistent Sharing of Fitness App Status on Twitter. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2016; Volume 27, pp. 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oyibo, K.; Olagunju, A.H.; Olabenjo, B.; Adaji, I.; Deters, R.; Vassileva, J. BEN’FIT: Design, implementation and evaluation of a culture-tailored fitness app. In Proceedings of the Adjunct Publication of the 27th Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, Larnaca, Cyprus, 6 June 2019; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, J.E.; Lepp, A.; Santo, A.; Glickman, E.; Dowdell, B. The relationship between fitness app use and physical activity behavior is mediated by exercise identity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keung, C.; Lee, A.; Lu, S.; O’Keefe, M. BunnyBolt: A mobile fitness app for youth. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, New York, NY, USA, 24–27 June 2013; pp. 585–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.S.; Wojcik, J.R.; Winett, R.A.; Williams, D.M. Social-cognitive determinants of physical activity: The influence of social support, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and self-regulation among participants in a church-based health promotion study. Health Psychol. 2006, 25, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyibo, K.; Orji, R.; Vassileva, J. Developing Culturally Relevant Design Guidelines for Encouraging Physical Activity: A Social Cognitive Theory Perspective. J. Health Inform. Res. 2018, 2, 319–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyibo, K.; Adaji, I.; Orji, R.; Olabenjo, B.; Azizi, M.; Vassileva, J. Perceived Persuasive Effect of Behavior Model Design in Fitness Apps. In Proceedings of the 26th Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, Singapore, 8–11 July 2018; pp. 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, A.; Bickmore, T.; Cange, A.; Kulshreshtha, A.; Kvedar, J. An Internet-Based Virtual Coach to Promote Physical Activity Adherence in Overweight Adults: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vollmer, J.; Schuster, P.; Giuliani, M. Plank Challenge with NAO: Using a Robot to Persuade Humans to Exercise Longer. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Persuasive Technology, Salzburg, Austria, 4–7 April 2016; pp. 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy, D.E.; Yang, C.-H.; Maher, J.P. Behavior Change Techniques in Top-Ranked Mobile Apps for Physical Activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 121–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Fountoukidou, S.; Ham, J.; Matzat, U.; Midden, C. Effects of an artificial agent as a behavioral model on motivational and learning outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stibe, A. Socially Influencing Systems: Persuading People to Engage with Publicly Displayed Twitter-Based Systems. 2014. Available online: http://urn.fi/urn:isbn:9789526205410 (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Lin, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-S.; Tsai, J.-C. Exploring the Triple Reciprocity of Information System Psychological Attachment; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 779–785. [Google Scholar]

- Fogg, B.J. Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 31–65. [Google Scholar]

- Oyibo, K.; Adaji, I.; Vassileva, J. Social cognitive determinants of exercise behavior in the context of behavior modeling: A mixed method approach. Digit. Health 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovniak, L.S.; Anderson, E.S.; Winett, R.A.; Stephens, R.S. Social cognitive determinants of physical activity in young adults: A prospective structural equation analysis. Ann. Behav. Med. 2002, 24, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R.; Renner, B. Social-cognitive predictors of health behavior: Action self-efficacy and coping self-efficacy. Health Psychol. 2000, 19, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcicki, T.; White, S.M.; McAuley, E. Assessing Outcome Expectations in Older Adults: The Multidimensional Outcome Expectations for Exercise Scale. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2009, 64, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breslin, S.; Wadhwa, B. Gender and Human-Computer Interaction. Wiley Handb. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2017, 1, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiano, S.; Borda, A.; Bowen, J.; Faulkner, X.; Gaia, G.; McDaid, S. Gender Issues in HCI Design for Web Access. In Advances in Universal Web Design and Evaluation: Research, Trends and Opportunities; Kur-niawan, S., Zaphiris, P., Eds.; Idea Group Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2006; pp. 116–153. [Google Scholar]

- Orji, R.; Mandryk, R.; Vassileva, J. Gender and Persuasive Technology: Examining the Persuasiveness of Persuasive Strategies by Gender Groups. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Persuasive Technology, Padova, Italy, 21 May 2014; pp. 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Oyibo, K.; Orji, R.; Vassileva, J. The Influence of Culture in the Effect of Age and Gender on Social Influence in Persuasive Technology. In Proceedings of the Adjunct Publication of the 25th Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, Bratislava, Slovakia, 12 July 2017; ACM: New York, NY, USA,; pp. 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullahi, A.M.; Oyibo, K.; Orji, R.; Kawu, A.A. The Influence of Age, Gender, and Cognitive Ability on the Susceptibility to Persuasive Strategies. Information 2019, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oyibo, K.; Vassileva, J. Investigation of persuasive system design predictors of competitive behavior in fitness application: A mixed-method approach. Digit. Health 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dağgöl, G.D. Perceived Academic Motivation and Learner Empowerment Levels of EFL Students in Turkish Context. Particip. Educ. Res. 2020, 7, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, I.M.; Kamins, M.A. Effectively using death in health messages: Social loss versus physical mortality salience. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 18, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.K.; Cohen, G.L. Accepting Threatening Information: Self–Affirmation and the Reduction of Defensive Biases. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 11, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, J.L.; Arndt, J. The implications of death for health: A terror management health model for behavioral health promotion. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 115, 1032–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyibo, K.; Vassileva, J. Investigation of the moderating effect of race-based personalization of behavior model design in fitness application. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Block, L.G.; Keller, P.A. When to Accentuate the Negative: The Effects of Perceived Efficacy and Message Framing on Intentions to Perform a Health-Related Behavior. J. Mark. Res. 1995, 32, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBCNews. Physical Inactivity Costs Taxpayers 6.8B a Year; Canadian Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/physical-inactivity-costs-taxpayers-6-8b-a-year-1.1134811 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Hodgson, C.; Corscadden, L.; Taylor, A.; Sebold, A.; Pearson, C.; Kwan, A.; Sommerer, S.; Halley, R.L.; Walsh, P.; Shane, A.; et al. Obesity in Canada: A joint report from the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Can. Inst. Health Inf. 2011, 62, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lavie, C.J.; Thomas, R.J.; Squires, R.W.; Allison, T.G.; Milani, R.V. Exercise training and cardiac rehabilitation in primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2009, 84, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Obesity in Canada. Available online: https://obesitycanada.ca/obesity-in-canada/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- McGaan, L. Introduction to Persuasion, Monmouth College. Available online: https://department.monm.edu/cata/rankin/Classes/Scat101/assignments/rational.htm (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Buhrmester, M.D.; Kwang, T.; Gosling, S. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, G. PLS Path Modeling with R. 2013. Available online: https://www.gastonsanchez.com/PLS_Path_Modeling_with_R.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.; Fangwei, Z.; Siddiqi, A.F.; Ali, Z.; Shabbir, M.S. Structural Equation Model for Evaluating Factors Affecting Quality of Social Infrastructure Projects. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunn, T.J.; Baguley, T.; Brunsden, V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br. J. Psychol. 2013, 105, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peters, G. userfriendlyscience: Quantitative Analysis Made Accessible. R Package. Version 0.3-0. 2015. Available online: https://rdrr.io/cran/userfriendlyscience/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Birrell, I. Obesity: Africa’s New Crisis. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/sep/21/obesity-africas-new-crisis (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Cialdini, R.B. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, revised ed.; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Oyibo, K.; Adaji, I.; Orji, R.; Olabenjo, B.; Vassileva, J. Susceptibility to persuasive strategies: A comparative analysis of Nige-rians vs. Canadians. In Proceedings of the 26th Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization—UMAP 2018, Singapore, 8–11 July 2018; pp. 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley, M.P. Family Communication at the End of Life. Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R. Weight Discrimination: A Socially Acceptable Injustice. Available online: http://www.obesityaction.org/wp-content/uploads/Obesity-Discrimination.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Andreyeva, T.; Puhl, R.M.; Brownell, K.D. Changes in Perceived Weight Discrimination among Americans, 1995–1996 through 2004–2006. Obesity 2008, 16, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.; Brownell, K. Bias, Discrimination and Obesity. Handb. Obes. 2008, 461–470, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity. Yale Study Shows Weight Bias Is as Prevalent as Racial Discrimination. Available online: https://news.yale.edu/2008/03/27/yale-study-shows-weight-bias-prevalent-racial-discrimination (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Oyibo, K. Designing Culture-Tailored Persuasive Technology to Promote Physical Activity. 2020. Available online: https://harvest.usask.ca/handle/10388/12943 (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Spörrle, M.; Bekk, M. Meta-Analytic Guidelines for Evaluating Single-Item Reliabilities of Personality Instruments. Assessment 2013, 21, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist, L.; Rossiter, J.R. The Predictive Validity of Multiple-Item versus Single-Item Measures of the Same Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 44, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Overall Question and Items |

|---|---|

| Health Message [Does not motivate me to start or continue exercising (1) to Completely motivates me to start or continue exercising (7)] | Please kindly rate the following messages below:

|

| Self-Efficacy [Not Confident (0) to Confident (100)] [33] | How confident are you that you can complete at home the proposed weekly number of push-ups (entered previously) for the next 3 months.

|

| Outcome Expectation [Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5)] [35] | The [name of exercise] will…

|

| Self-Regulation [Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5)] [31] | To achieve my proposed weekly average number of push-ups…

|

| Criterion | Subgroup | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 327 | 48.9% |

| Male | 342 | 51.1% | |

| Age | 18–24 | 126 | 18.8% |

| 25–34 | 296 | 44.2% | |

| 35–44 | 155 | 23.2% | |

| 45–54 | 60 | 9.0% | |

| 54+ | 32 | 4.8% | |

| Education | Tech/Trade School | 86 | 12.9% |

| High School | 136 | 20.3% | |

| BSc | 316 | 47.2% | |

| MSc | 96 | 14.3% | |

| PhD | 15 | 2.2% | |

| Others | 20 | 3.0% | |

| Canada | 214 | 32.0% | |

| Country of Origin | United States | 378 | 56.5% |

| Others | 77 | 11.5% | |

| Race | Black | 52 | 7.8% |

| Brown | 99 | 14.8% | |

| White | 518 | 77.4% | |

| Observer– Model Race | BB | 74 | 11.1% |

| BW | 78 | 11.7% | |

| WW | 255 | 38.1% | |

| WB | 262 | 39.2% | |

| Years on the Internet | 0–3 | 4 | 0.6% |

| 4–6 | 31 | 4.6% | |

| 7–9 | 60 | 9.0% | |

| >10 | 574 | 85.8% |

| Message Type | Self-Efficacy | Self-Regulation | Outcome Expectation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | Sig | M | F | Sig | M | F | Sig | |

| Money | 0.14 | 0.15 | p < 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.00 | n.s | 0.10 | 0.06 | n.s |

| Obesity | 0.07 | −0.04 | n.s | 0.06 | 0.05 | n.s | 0.06 | 0.21 | n.s |

| Illness | 0.16 * | 0.11 | n.s | 0.20 * | 0.16 * | n.s | 0.17 * | 0.03 * | n.s |

| Death | 0.12 | 0.06 | n.s | 0.24 * | 0.21 * | n.s | 0.19 * | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Stigma | 0.02 | 0.17 * | p < 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.11 | n.s | 0.08 | 0.14 *** | p < 0.05 |

| R2 | 14% | 13% | 22% | 18% | 21% | 18% | |||

| GOF | 33% | 31% | 32% | 36% | 31% | 28% | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oyibo, K. The Relationship between Perceived Health Message Motivation and Social Cognitive Beliefs in Persuasive Health Communication. Information 2021, 12, 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12090350

Oyibo K. The Relationship between Perceived Health Message Motivation and Social Cognitive Beliefs in Persuasive Health Communication. Information. 2021; 12(9):350. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12090350

Chicago/Turabian StyleOyibo, Kiemute. 2021. "The Relationship between Perceived Health Message Motivation and Social Cognitive Beliefs in Persuasive Health Communication" Information 12, no. 9: 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12090350

APA StyleOyibo, K. (2021). The Relationship between Perceived Health Message Motivation and Social Cognitive Beliefs in Persuasive Health Communication. Information, 12(9), 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12090350