Abstract

Gamification, commonly defined as the use of game elements in non-game contexts, is a relatively novel term, yet it has been gaining popularity across a wide range of academic and industrial disciplines. In the marketing field, companies are increasingly gamifying their mobile apps and online platforms to enrich their customers’ digital experiences. Whilst there has been a number of systematic studies examining the influence of gamification on user engagement across different fields, none has reviewed its role in brand value co-creation. Following a systematic literature review procedure via the online research platform EBSCOhost, this paper is the first to survey a set of empirical studies examining the role and impact of gamification on brand value co-creation. A final pool of 32 empirical studies implies the existence of four types of activities that are co-created by online users and positively influenced by gamification, namely: customer service, insights sharing, word-of-mouth, and random task. Moreover, this paper highlights the major game dynamics driving these activities, the key findings of each of the covered studies and their main theoretical underpinnings. Lastly, a set of noteworthy research directions for future related studies are suggested, comprising the exploration of novel game elements, and new co-creation activities related to corporate social responsibilities and physical commercial operations.

1. Introduction

Although relatively novel, the term of gamification, which first emerged around 2010, has since gained fast recognition across both the scholarly and practical domains [1]. Principally targeting users’ engagement in order to promote behavioural changes [2,3], gamification is majorly defined as the use of game elements in non-game contexts [4]. It is comprised of game mechanics—also known as game functional components—such as points and leader boards, which in turn spark compatible game dynamics that trigger players’ desires, like rewards and competition [5]. Although gamification can take the form of card decks and board games, modern gamified systems are mostly employed via digital means, such as web-based and mobile-based applications [6].

Nowadays, gamification has been widely applied in the educational and business sectors to promote engagement [7,8] and game elements are becoming increasingly embedded in students’ learning processes [9] and employees’ daily tasks [10]. Recently, an emerging base of evidence presented gamification as a promising strategy for improving students’ learning [11,12] and employees’ productivity [13,14].

Aside from its internal use in workplaces, business companies are also gamifying their external marketing activities, aiming to improve the digital experience of both current and potential customers [15]. While the broad concept of gamification “in” the marketing context embraces three types of gamified advertisements known as “Advergames”, “In game advertisement” and “social network games” [16], these three do not meet the academic criteria of this term [17]. In contrast with the basic definition of gamification, known as the use of game elements in non-game contexts, they actually adopt a distinct model, promoting advertisements throughout entertainment games. In the marketing literature, gamification has been primarily presented as the practice of adding a sense of value to mundane activities [18] or, as elaborated by Huotari and Hamari [1] (p. 25), “the process of enhancing a service with affordances for gameful experiences in order to support users’ overall value creation”.

As emphasised by Brodie et al. [19], customers’ engagement is often driven by their psychological perceptions towards the brand. This has been supported by a systematic review conducted by Tobon et al. [3], which highlighted five main psychological theories often referred to in assessing the marketing implications of gamification. The five theories are: self-determination theory, technology acceptance model, theory of planned behaviour, flow theory, and social-influence theory. Although the influence of gamification on customer engagement has been reviewed in the literature from further theoretical perspectives, most of these were of a psychological nature, which reflects the fundamental role of users’ psychology in mediating the effect of gamification on their behavioural outcomes and value creation experiences [1].

The concept of value creation, traditionally shaped from the research streams of the service dominant logic, service logic and customer-dominant logic, has been originally regarded as the independent perception that consumers tend to conceive towards a service quality, either during or after the consumption process [20]. As per the service-dominant logic, this could be viewed as a joint, but indirect, creation between the firms and their consumers who use their knowledge and skills to continue the marketing, consumption, and value creation process [21]. With customers tending to demand more active roles in production and decision making [22], firms no longer perceive them as passive targets [23]. Instead, they are opening their processes and systems for consumers to craft customised consumption experiences [24] and get involved in new product/service development [25]. This conceptual shift from customer value creation to value co-creation has been significantly boosted by the rise of the internet [25] and the emergence of social media networks [26]. According to Nambisan and Nambisan [27], customer co-creation in virtual communities has been associated with five key roles, namely: product conceptualiser, product designer, product tester, product support specialist and product marketer. All through the rapid expansion of this phenomenon, a more advanced version known as “crowdsourcing’ has surfaced, where firms structurally use their customers’ collective intelligence to deliver specific and well-constructed tasks [28].

As firms are increasingly launching online forums to incite their communities’ engagement [29] and open their innovation processes up for customers’ contribution [30,31], studies are increasingly exploring the role of intrinsic and extrinsic factors in motivating customers to participate in virtual co-creation communities. Accordingly, Lakhani et al. [32] highlighted the salient role of monetary rewards and task enjoyment, whereas Brabham [33] pointed to people’s desire to develop self-creative skills, build networks and support the community. Furthermore, Füller [34] summarised the most prevalent factors in the literature in ten main aspects, namely: playfulness, curiosity, self-efficacy, skill development, information seeking, recognition, community support, making friends, personal need, and monetary compensation.

Since consumers are generally fun seekers in nature [35], companies are progressively gamifying their virtual co-creative platforms to trigger users’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivations [36]. As per Füller [34], these motivations are the key drivers of customers’ engagement in online co-creation activities, as it immerses them in flowing experiences through which they impulsively stretch their skills to optimally achieve clearly defined goals and tasks [37]. All across the gamification literature, the concept of customers’ value co-creation has been interpreted in two different contexts. One is regarded as “experience value co-creation” [38,39], where customers’ contribution is merely limited to their participation in a gamified experience that ultimately seeks to increase their brand loyalty. The second, known as “brand value co-creation” [40] refers to their involvement in business-related activities, such as promoting, advocating, collaborating, and sharing knowledge with their companies [41], leading in turn to brand innovation and growth [42]. In brand value co-creation, “there is still lack of clarity in identifying different dimensions that constitute value for company” [43] (p. 452), which highlights the need for “more thorough exploration of the goals the companies seek and techniques of consumer engagement the companies use for it” [43] (p. 452).

Recently, numerous studies have systematically surveyed the use of gamification in different contexts, yet none have explored the influence of gamification on brand value co-creation. Through a systematic literature review, this paper addresses this gap and seeks to gauge the impact of gamified experiences on consumers’ willingness to co-create, and the key factors promoting it. Hence, this paper aims to identify the different types of co-creation activities that are positively affected by gamification, along with the key game dynamics driving them.

2. Materials and Methods

All the way through attaining and managing an evidence-informed knowledge in the designated research context, a systematic review model is processed. This methodology has been chosen because of its transparent, effective, and comprehensible approach in gathering and analysing information [44]. Subsequently, a structured review protocol comprising of the key stages in management studies [45] has been developed as follows:

- First, in an attempt to scan the widest number of relevant papers in the context of gamified co-creative environments, EBSCOhost online research platform was selected. The covered databases were EBSCO’s private library, Gale Academic OneFile, The Directory of Open Access Journals, in addition to the four major databases embracing the largest number of papers in the subject area: ScienceDirect, Springer, Emerald and IEEE Xplore [46].

- As gamification is only beginning to get substantial academic recognition since around 2010, the search query was set to cover the period between 2010 and 2020. Using the Boolean research technique for results’ filtration and irrelevancy minimisation [47], the first search covered all papers that comprised a conjunction of the term “gamification” with each of the following terms in their abstract section: “GAMIFICATION and CO-CREATION” or “GAMIFICATION and CROWDSOURCING” or “GAMIFICATION and SHARING ECONOMY” or “GAMIFICATION and CUSTOMER(S)” or “GAMIFICATION and CONSUMER(S)” or “GAMIFICATION and ONLINE and USER(S)”. These terms were prudently selected, given their remarkable predominance across dozens of randomly selected papers in relation to the context of study, just prior to pursuing the searching process. The first stage of the search, which only covered papers written in English, resulted in a sample of 1073 papers, which were then automatically reduced to 783 following an exact-duplications removal.

- Next, search inclusion criteria were set to solely hedge quality academic papers. Thus, only peer-reviewed academic articles and conference papers were filtered, leading to a result of 571 papers.

- Subsequently, a manual check for each of the collected papers was processed to ensure that only empirical studies that examine the use of gamification for brand value co-creation in the B2C sector are kept. Consequently, 33 relevant papers were retained.

- Finally, to ensure that no relevant articles were missed, a further manual check of the 571 papers was conducted. The revision has conversely resulted in withdrawing one paper out of the adopted pool, as it merely examines the impact of gamification on gig workers rather than end users, which does not match with the “B2C” inclusion criterion in the review protocol. The final number of adopted papers thus dropped to 32.

3. Results

This section features the key outcomes of the systematic literature review. In Table 1, a summary of the main empirical findings and their underpinning theories across the 32 studies is presented.

Table 1.

Key findings of the surveyed case studies.

All the papers consisted of empirical studies that assess the role of gamification in online co-creation platforms—mainly websites and mobile apps—with only one study incorporating a further augmented-reality experience in a virtual smart store context [68]. Among the thirty-two studies, twenty-three are involved in real-life business cases, sixteen are associated with businesses of crowdsourcing nature, and four are related to the sharing economy industry which has been significantly thriving in recent years [36].

3.1. Co-Creation Activities

The examined gamified platforms promoted different sorts of co-creation activities across various industries, yet these diverse activities clearly manifested clusters of mutual characteristics. In order to identify each of these clusters, every single activity was scrutinised and associated with the ultimate objective it has been created for. Subsequently, four generic categories emerged, as follows:

- Word-of-mouth (WOM): Referring to all kinds of online endorsements that users perform in promoting a brand or any of its products or services, either by sharing and forwarding brand related contents or inviting friends to join the community, e.g., recommending people to join “Samsung Nation” [72].

- Insights sharing: Implying all sorts of insightful information users provide to a company. This can take the form of systemised tasks, such as undertaking surveys, voting on suggestions, and sharing live data, e.g., participating in paid surveys at “Amazon Mechanic Turk” [73], voting on proposals at “Threadless” [69] or sharing live road data to “My Drive Assist” app [55].

On the other hand, the collection of insights can be formless, whereby users impulsively share their ideas, feedback, and recommendations with their companies, e.g., expressing ideas and opinions at “Huawei” and “Xiaomi” online platforms [57].

- Customer service: Comprising all types of online assistance users provide to each other, such as answering questions, solving technical issues, or submitting helpful ratings and informative reviews about products or services, e.g., resolving users’ IT enquiries on “StackOverflow” [65] or providing hotel/restaurants ratings and reviews on “TripAdvisor” [56,71].

- Random task: Involving all other activities besides “WOM”, “Insights sharing” and “Customer service”. This typically refers to on-demand tasks in crowdsourcing platforms or trading tasks in sharing economy websites, e.g., delivering projects on “ZBJ” [62] or posting trade proposals on “Sharetribe” [36].

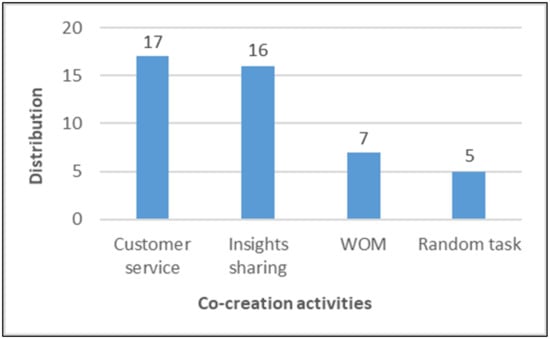

Following a thorough data analysis of the findings presented in Table 1, the statistics displayed in Figure 1 show that “customer service” and “insights sharing” are the most prevalent types of co-creation activities, appearing in 17 and 16 studies, respectively, followed by a seven-time appearance of “WOM” and five-time appearance of “random task”.

Figure 1.

Distribution of co-creation activities across the surveyed case studies.

3.2. Game Dynamics

Just like the discrepancy in defining the game dynamics’ elements throughout the literature [8], the reported papers similarly used inconsistent terms and notions. Hence, one consistent terminology has been developed in this study, adopting the terms and notions that were mostly referred to all across the papers.

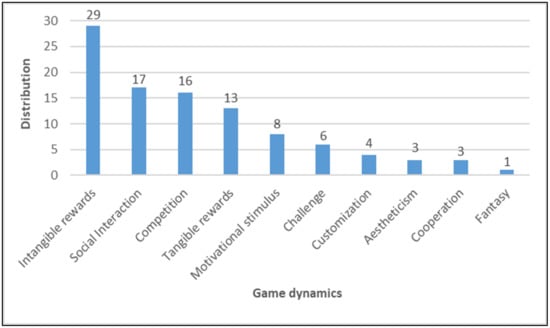

The statistics in Figure 2 show that “intangible rewards”, mainly carried through points and badges [75,76], is the most dominant game dynamic across all the case studies, appearing in 29 cases. The second most prevalent game dynamic is “social interaction”, typically triggered by social drivers such as altruism and reciprocity [60,65], sense of belonging [57,71] and social network building [66,69]. Very close to “social interaction” falls “competition”, commonly manifested through ranking tables and leader boards [58], then “tangible rewards” implying monetary prizes and gifts [75,76] with a respective appearance in 17, 16 and 13 case studies.

Figure 2.

Distribution of game dynamics across the surveyed case studies.

It is also worth mentioning that the remaining game dynamics which were less prevalent in the surveyed case studies have no cohesive conception in the gamification academic repertoire; however, they are generally recognised in the literature for embracing the following mechanics:

- Motivational stimulus: Progress bar; scoring system; instant messages [48,62,69]

- Challenge: Missions with success/failure outcomes; challenging rules; time pressure [59,68,77]

- Customisation: Avatars; personalised features [40,49,52]

- Aestheticism: Attractive visual design; narrative stories [49,52,57]

- Cooperation: Collaborative tasks and missions [41,58,63]

- Fantasy: Exciting experiences carried through fascinating features and/or advanced technologies [68,78,79].

3.3. The Crowdsourcing Industry

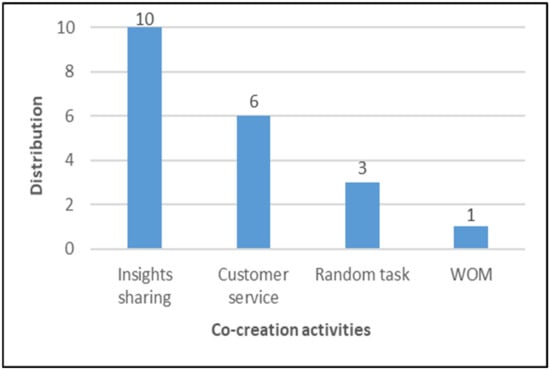

The statistics in Figure 3, which solely feature data from the crowdsourcing platforms, show that insights sharing is by far the most frequently employed type of co-creation activity, followed by “customer service”, “random task” and “WOM”.

Figure 3.

Distribution of co-creation activities across “crowdsourcing” case studies.

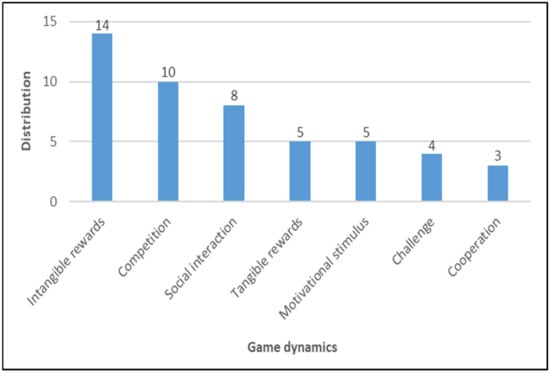

Furthermore, a significant ranking swap between “competition” and “social interaction” across crowdsourcing platforms was spotted, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Distribution of game dynamics across “crowdsourcing” case studies.

3.4. Underpinning Theories

Although the surveyed studies were conducted in various fields and throughout different methodologies, Table 2 highlights the prominent theories underpinning most of these studies, along with the key findings associated with each theory.

Table 2.

Major underpinning theories and their related findings across the surveyed case studies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Results Interpretation

Besides interpreting the key findings of this study, this section points out a set of limitations and innovative research directions to be addressed in the future.

Despite the wide adoption in the literature of Huotari and Hamari’s [1] proposed definition of gamification as a process for supporting users’ overall value creation, there is still no unified understanding of such a value [20] and no way to clearly observe it empirically [63]. Upon identifying two types of users’ value co-creation that are endorsed by gamification, labelled “experience value co-creation” and “brand value co-creation”, the systematic survey conducted in this paper regarding the latter has revealed major findings to build on in future research.

Applying gamification in online platforms is found to positively influence four major types of activities that are co-created by users. In the conventional form of the business-to-consumer sector, firms are primarily using their gamified systems to encourage their users to undertake “customer service” and “insights sharing” activities, obviously given their impact on leveraging brands’ familiarity and innovation. Crowdsourcing companies, in turn, are primarily using gamification to promote “insights sharing”, followed by “customer service” and “random task”. Surprisingly, word-of-mouth, which has been traditionally recognised as a key aspect in brand value co-creation [80], appeared in less than quarter of the thirty-two reported studies. In a primitive interpretation of this paradox, this could be linked to the findings of Nobre and Ferreira [40], who revealed consumers’ impulsive tendency to spread positive word-of-mouth when enjoying the gamified experience, thus limiting firms’ need to promote such a “spontaneous” activity through hedonic or utilitarian incentives. Moreover, all of the identified “random task” activities in the surveyed papers were remarkably executed within the sharing economy and crowdsourcing industries, where a large segment of firms promote trading activities and on-demand business projects respectively.

On the other hand, the data analysis of the employed game dynamics highlights a predicted predominance of “intangible rewards” across all the studied cases, given its pivotal role in promoting all other dynamics. Surprisingly, the prominent role given to “tangible rewards” in the literature was slightly surpassed by “social interaction” and “competition”. This matches with the findings of Kavaliova et al. [69], who claimed users’ inclination for fun and enjoyment over tangible returns when engaged in gamified experiences. In the crowdsourcing industry, “competition” is ranked second just after “intangible rewards”, apparently reflecting the fierce environment companies tend to promote in this sector in order to get the most out of their employed contestants [81].

From a theoretical perspective, most of the prevalent marketing theories that were referred to across the surveyed studies match with those previously reported by Tobon et al. [3]. Additionally, the goal-setting theory, largely related to the flow theory, was found to be used in three studies. Furthermore, other social-related theories beyond “social influence” were reported, specifically: social-cognitive, social-comparison, social-exchange and social-proof theories. The findings of the studies involving these social-related theories showcase that, when it comes to brand value co-creation, users’ psychology is fundamentally correlated with the perceived social value generating from their gamified experiences.

Overall, the findings of this study underline a positive correlation between users’ enjoyment of the gamified experience and their intention to contribute to brand value creation. This relationship is found to be typically mediated by the hedonic value of various types of game dynamics that range from “intangible rewards”, “social interactions”, and “competition”, to some less prominent ones, such as “motivational stimulus”, “challenge” “customisation”, “aestheticism, and “cooperation”. It has been also realised that, unlike other game dynamics, “social interactions” plays a unique dual role that involves both hedonic and utilitarian values, whereby users concurrently enjoy the social interface and harness it to gain knowledge, promote their ideas, and build their private social networks. Tangible rewards on the other hand, merely providing utilitarian values [82], are found effective, yet less essential in shaping users’ value co-creation experiences.

4.2. Limitations

Despite its insightful and promising outcomes, this paper has some limitations that could be further elaborated in future related research. First, the papers’ scanning stage in the employed methodology was limited to one bibliographic search provider. Although major academic databases were selected, employing further search engines could have been of benefit. On the other hand, the paper only involves empirical studies in an attempt to understand the impact of gamification on brand value co-creation; however, plenty of real-life examples in various industries were omitted because no concrete findings are available to examine. Such missed opportunities should be addressed in future empirical studies, especially with respect to emerging industries such as the sharing economy which was only covered in this paper through four examples, two out of which related to the same brand named “Sharetribe”. Another limitation embedded in this study lies in grouping together a wide range of co-creation activities under one proposed class, labelled as “random task”. As random tasks could vary from very simple activities to highly professional projects, future studies can refine this further and split it into more visible sections. Such a segregation could be based on different criteria, such as the level of skills required from users, tasks’ delivery time, or even the types of business industries these tasks belong to.

Furthermore, this study reviews the influence of gamification on users at a general scale, with no adequate information on their demographic attributes which could definitely help in better understanding the attitudes and behaviour of users towards gamified systems. The studied cases also lacked an examination of the actual and prospective implications of negative experiences on users’ satisfaction and brand loyalty. Finally, although gamification was proven to be significantly effective in encouraging users to engage in co-creation activities, this has been majorly associated with their short-term monitored behaviour. As implied by Tobon et al. [3], there are still many doubts regarding the effectiveness of gamification on users’ momentum on the long run.

4.3. Future Research Directions

In accordance with to the above-mentioned tips, future research should primarily consider gathering users’ demographic attributes, as highlighted by Köse et al. [55], Nobre and Ferreira [40] and Ruiz-Alba et al. [59]. This can also include other aspects, such as their previous experiences and familiarity with game-based systems, as suggested by Xi and Hamari [57]. Indeed, this could serve to not only increase understanding of the behaviour of active users, but also passive and reluctant ones. Accordingly, further theories not previously approached in the literature could potentially be considered, such as the expectancy-value theory and the expectation-confirmation theory, in order to evaluate the impact of users’ presumptions on their actual behaviour. On the other hand, the implications of negative gamified experiences and the misuse of game mechanics should also be explored, whereby many signs of users’ dissatisfaction have been noticed and need further investigations [41,69,72].

Above all, this literature review opens the floor for further studies to explore novel ideas around the use of gamification for brand value co-creation. The intriguing fantasy dynamic driven by the in-store technology interface example [68] raised the importance of considering innovative gaming features. This might involve the application of advanced technologies, such as augmented reality, virtual reality and mixed reality. On the other hand, the promising findings of the virtual CSR experiment [54] highlighted the potential role of gamification in promoting end-users’ contribution to actual CSR activities. Although real-life examples in this field might be limited, this certainly reflects a major opportunity for researchers to undertake conceptual and experimental related studies. Last but not least, the digital nature of the “random task” activities reported in this paper opens the scope for researchers to explore the possibility of using gamification for fostering users’ co-creation of physical tasks, typically with respect to commercial operations encompassing sales and merchandising activities.

5. Conclusions

With firms’ emerging tendency to involve their customers in their business processes, increasing interest is devoted to the concept of customer value co-creation. While this concept basically refers to creating mutual value for both the company and the consumer, the use of gamification has addressed it from two main perspectives: one that denotes a merely entertaining experience which increase users’ brand loyalty, and another with a further objective of availing their inputs in support of brand value creation. This systematic survey, reporting on a set of empirical studies, has revealed the existence of four major types of brand value co-creation activities that are promoted throughout various game dynamics of disparate levels of impact. Although gamification is showing significant effectiveness in motivating customers to engage in online communities and contribute to brand value creation, very few of these studies investigate the influence of gamification on long-term outcomes, as well as the implications of negative experiences on users’ overall satisfaction. Demographic factors should also be studied in order to better understand the attitude and behaviour of active and passive users, possibly with reference to new marketing theories beyond the predominant ones. We also recommend further exploration of the role and impact of gamification in the rapidly growing sharing economy industry which is rarely discussed in the literature. Finally, we shed light on the potential inclusion of advanced gaming technologies that could further energise users’ experiences, as well as considering gamifying additional co-creation activities that were not outlined in the literature but are typically related to physical commercial operations and corporate social responsibilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.A.M., P.P. and R.K.; methodology, M.A.M.; software, M.A.M.; validation, M.A.M.; formal analysis, M.A.M.; investigation, M.A.M.; resources, M.A.M.; data curation, M.A.M. and R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.M.; writing—review and editing, M.A.M., P.P. and R.K.; visualisation, M.A.M. and R.K.; supervision, P.P.; project administration, M.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Huotari, K.; Hamari, J. A definition for gamification: Anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electron. Markets 2017, 27, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoech, D.; Boyas, J.F.; Black, B.M.; Elias-Lambert, N. Gamification for behavior change: Lessons from developing a social, multiuser, Web-tablet based prevention game for youths. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2013, 31, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobon, S.; Ruiz-Alba, J.L.; García-Madariaga, J. Gamification and online consumer decisions: Is the game over? Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 128, 113167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zichermann, G.; Cunningham, C. Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps, 1st ed.; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Patrício, R.; Moreira, A.C.; Zurlo, F. Gamification approaches to the early stage of innovation. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2018, 27, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridis, P.; Hadjicosta, K.; Shi, V.G.; Dunwell, I.; Baines, T.; Bigdeli, A.; Bustinza, O.F.; Uren, V. State-of-the-Art in business games. Int. J. Serious Games 2015, 2, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szendrői, L.; Dhir, K.S.; Czakó, K. Gamification in for-profit organisations: A mapping study. Bus. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.; Doyle, E. Gamification and student motivation. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 24, 1162–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Schuster, L.; Seung Jin, H. Gamification and the impact of extrinsic motivation on needs satisfaction: Making work fun? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 106, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putz, L.M.; Hofbauer, F.; Treiblmaier, H. Can gamification help to improve education? Findings from a longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 110, 106392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M.; Homner, L. The gamification of learning: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 32, 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, E.T.; Camblin, J.G.; Jones, F.D.; Wine, B. On the implementation of a gamified professional development system for direct care staff. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 2019, 39, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Burgers, M.J.; Kaan, A.M.; Lamberts, B.F.; Migchelbrink, K.; Van den Ouweland, R.C.P.M.; Meijer, T. Gamification in Dutch Businesses: An Explorative Case Study. SAGE Open 2020, 43, 729–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does gamification work? A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th HI International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 3025–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlutter, R.; Capella, M.L. The Gamification of advertising: Analysis and research directions of in-game advertising, advergames, and advertising in social network games. J. Advert. 2013, 42, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Chen, M. How gamification marketing activities motivate desirable consumer behaviors: Focusing on the role of brand love. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 88, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridis, P.; Hadjicosta, K.; Dunwell, I.; Lameras, P.; Baines, T.; Shi, V.G.; Ridgway, K.; Baldin, J.; Lightfoot, H. Gamification: Using gaming mechanics to promote a business. In Proceedings of the Spring Servitization Conference, Birmingham, UK, 2–14 May 2014; Aston University: Birmingham, UK, 2014; pp. 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Juric, B.; Ilic, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.V. Value co-creation in service marketing: A critical (re)view. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2019, 3, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, A.F.; Venkatesh, A. Liberatory Postmodernism and the reenchantment of consumption. J. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 239–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapscott, D.; Williams, A.D. Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything; Penguin Group: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Firat, A.F.; Dholakia, N.; Venkatesh, A. Marketing in a postmodern world. Eur. J. Mark. 1995, 29, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hern, M.; Rindfleisch, A. Customer co-creation: A typology and research agenda. Rev. Mark. Res. 2010, 6, 84–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rathore, A.K.; Ilavarasan, P.V.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Social media content and product co-creation: An emerging paradigm. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2016, 29, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Nambisan, P. How to profit from a better ‘virtual customer environment’. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2008, 49, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, R.; Booij, E.; Spruit, M. Reaching out: Involving users in innovation tasks through social media. In Proceedings of the ECIS 2012 Proceedings, Barcelona, Spain, 6 June 2012; p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Castle, N.W.; Combe, I.A.; Khusainova, R. Tracing social influence in responses to strategy change in an online community. J. Strateg. Mark. 2014, 22, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M.; Schultz, M. Toward a theory of brand co-creation with implications for brand governance. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani, K.R.; Jeppesen, L.B.; Lohse, P.A.; Panetta, J.A. The Value of Openness in Scientific Problem Solving; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brabham, D.C. Crowdsourcing as a model for problem solving: An introduction and cases. Converg. Int. J. Res. New Media Technol. 2008, 14, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füller, J. Refining virtual co-creation from a consumer perspective. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2010, 52, 98–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C.; Holbrook, M.B. Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J. Do badges increase user activity? A field experiment on the effects of gamification. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Csikzentmihaly, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A.; Schlager, T.; Sprott, D.E.; Herrmann, A. Gamified interactions: Whether, when, and how games facilitate self–brand connections. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 46, 652–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, J.; Ramberg, M.O.; Gustafsson, A.; Wästlund, E. Creating brand engagement through in-store gamified customer experiences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, H.; Ferreira, A. Gamification as a platform for brand co-creation experiences. J. Brand Manag. 2017, 24, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, T.; Poncin, I.; Hammedi, W. The Engagement process during value co-creation: Gamification in new product-development platforms. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2017, 21, 454–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedergaard, N.; Gyrd-Jones, R. Sustainable brand-based innovation: The role of corporate brands in driving sustainable innovation. J. Brand Manag. 2013, 20, 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piligrimiene, Z.; Dovaliene, A.; Virvilaite, R. Consumer engagement in value co-creation: What kind of value it creates for company? Eng. Econ. 2015, 26, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojania, K.G.; Sampson, M.; Ansari, M.T.; Ji, J.; Doucette, S.; Moher, D. How quickly do systematic reviews go out of date? A survival analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorbehbahani, F.; Salehi, F.; Zadeh, R.J. A systematic mapping study on gamification applied to e-marketing. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2019, 13, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiem, A.; Duşa, A. Boolean minimization in social science research: A review of current software for qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2013, 31, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Goh, D.; Lim, E. Understanding continuance intention toward crowdsourcing games: A longitudinal investigation. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prott, D.; Ebner, M. The use of gamification in gastronomic questionnaires. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2020, 14, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Shao, Z.; Li, X.; Feng, Y. Gamification and online impulse buying: The moderating effect of gender and age. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 102267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajarian, M.; Hemmati, S. A gamified word of mouth recommendation system for increasing customer purchase. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Smart City, Internet of Things and Applications (SCIOT), Mashhad, Iran, 16–17 September 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, N.; Hamari, J. Does gamification affect brand engagement and equity? A study in online brand communities. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Costello, F.J.; Lee, K.C. The Unobserved heterogeneneous influence of gamification and novelty-seeking traits on consumers’ repurchase intention in the omnichannel retailing. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, F.; Jiao, J.; Lin, P. Influence of virtual CSR gamification design elements on customers’ continuance intention of participating in social value co-creation: The mediation effect of psychological benefit. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 1305–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, D.B.; Morschheuser, B.; Hamari, J. Is it a tool or a toy? How user’s conception of a system’s purpose affects their experience and use. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, S.; Ramos, P.; Esmerado, J.; Jalali, S.M.J. Can we trace back hotel online reviews’ characteristics using gamification features? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, N.; Hamari, J. Does gamification satisfy needs? A study on the relationship between gamification features and intrinsic need satisfaction. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 46, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morschheuser, B.; Hamari, J.; Maedche, A. Cooperation or competition—When do people contribute more? A field experiment on gamification of crowdsourcing. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2019, 127, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Alba, J.L.; Soares, A.; Rodriguez-Molina, M.A.; Banoun, A. Gamification and entrepreneurial intentions. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2019, 26, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adornes, G.S.; Muniz, R.J. Collaborative technology and motivations: Utilization, value and gamification. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2019, 16, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczyński, K.; Zakrzewicz, M. Reviews with revenue in reputation: Credibility management method for consumer opinion platforms. Inf. Syst. 2019, 84, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Ye, J.H.; Yu, Y.; Yang, C.; Cui, T. Gamification artifacts and crowdsourcing participation: Examining the mediating role of intrinsic motivations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 81, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, T.; Hammedi, W.; Poncin, I. The boundaries of gamification for engaging customers: Effects of losing a contest in online co-creation communities. J. Interact. Mark. 2018, 44, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, F.; Furtado, F.; Filho, E. Stepbox: A proposal of share economy transport service. In Proceedings of the 13th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Caceres, Spain, 13–16 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penoyer, S.; Reynolds, B.; Marshall, B.; Cardon, P.W. Impact of users’ motivation on gamified crowdsourcing systems: A case of StackOverflow. Issues Inf. Syst. 2018, 14, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Kwon, S.; Na, H.; Chang, B. Factors affecting the adoption of gamified smart tourism applications: An integrative approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Schuckert, M.; Law, R.; Chen, C. Be a “Superhost”: The importance of badge systems for peer-to-peer rental accommodations. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poncin, I.; Garnier, M.; Ben Mimoun, M.; Leclercq, T. Smart technologies and shopping experience: Are gamification interfaces effective? The case of the smartstore. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 121, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaliova, M.; Virjee, F.; Maehle, N.; Kleppe, I.A. Crowdsourcing innovation and product development: Gamification as a motivational drive. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2016, 3, 1128132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goes, P.B.; Guo, C.; Lin, M. Do incentive hierarchies induce user effort? Evidence from an online knowledge exchange. Inf. Syst. Res. 2016, 27, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. The application and impact of gamification funware on trip planning and experiences: The case of TripAdvisor’s funware. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, T.; Garry, T. An investigation into gamification as a customer engagement experience environment. J. Serv. Mark. 2015, 29, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conaway, R.; Garay, M. Gamification and service marketing. SpringPlus 2014, 3, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J. Transforming homo economicus into homo ludens: A field experiment on gamification in a utilitarian peer-to-peer trading service. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013, 12, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ca Ziesemer, A.; Müller, L.; Silveira, M.S. Just Rate It! Gamification as part of recommendation. In Proceedings of the Human-Computer Interaction, Applications and Services, Crete, Greece, 22–27 June 2014; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meder, M.; Plumbaum, T.; Raczkowski, A.; Jain, B.; Albayrak, S. Gamification in ecommerce: Tangible vs. intangible rewards. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Academic Mindtrek Conference, Tampere, Finland, 10–11 October 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.; Pritchard, G.; Kernohan, H. Gamification in market research: Increasing enjoyment, participant engagement and richness of data, but what of data validity? Int. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 57, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.T.; Lee, W.H. Dynamical model for gamification of learning (DMGL). Multimed. Tools Appl. 2015, 74, 8483–8493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, G.P.; Wigati, E.K.; Utomo, Y.; Suryapranatac, L.K.P. Analysis of gamification models in education using MDA framework. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 135, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See-To, E.; Ho, K. Value co-creation and purchase intention in social network sites: The role of electronic word-of-mouth and trust—A theoretical analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevo, D.; Kotlarsky, J. Scoping Review of Crowdsourcing Literature: Insights for IS Research. In Information Systems Outsourcing; Hirschheim, R., Heinzl, A., Dibbern, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, V.G.; Baines, T.; Baldwin, J.; Keith, R.; Petridis, P.; Bigdeli, A.Z.; Uren, V.; Andrews, D. Using gamification to transform the adoption of servitization. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 63, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).