Cyclists’ Crossing Intentions When Interacting with Automated Vehicles: A Virtual Reality Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Apparatus

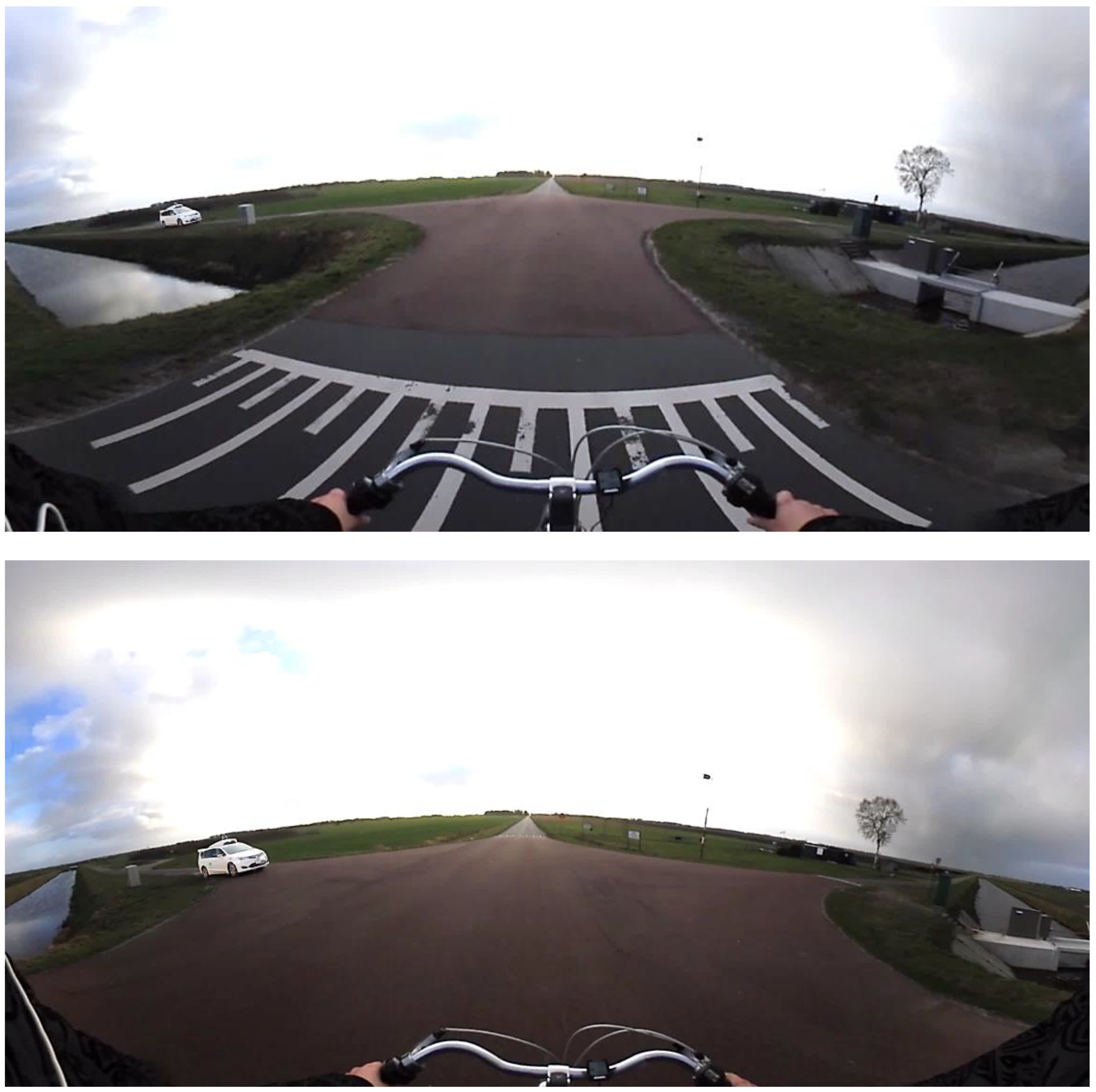

2.2. Location

2.3. Pilot Studies

2.4. Sample

2.5. Questionnaires

2.6. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Crossing Intentions

3.3. Perceived Behavioral Control and Perceived Risk

3.4. Models Per Session

3.5. Performance of the VR Method

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- SWOV. 2017. Available online: https://www.swov.nl/feiten-cijfers/factsheet/fietsers (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Pucher, J.; Buehler, R. Cycling towards a more sustainable transport future. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, K.; Abobakr, A.; Nahavandi, D.; Iskander, J.; Attia, M.; Hossny, M.; Nahavandi, S. Cyclist Intent Prediction using 3D LIDAR Sensors for Fully Automated Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, C.G.; Gavrila, D. Will the Pedestrian Cross? A Study on Pedestrian Path Prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2014, 15, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Färber, B. Pedestrians at the kerb—Recognising the action intentions of humans. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grembek, O.; Kurzhanskiy, A.; Medury, A.; Varaiya, P.; Yu, M. Making Intersections Safer with I2V Communication. Available online: https://par.nsf.gov/servlets/purl/10101212 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Hagenzieker, M.; Van Der Kint, S.; Vissers, L.; Van Schagen, I.N.L.G.; De Bruin, J.; Van Gent, P.; Commandeur, J.J.F. Interactions between cyclists and automated vehicles: Results of a photo experiment. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2020, 12, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merat, N.; Louw, T.; Madigan, R.; Wilbrink, M.; Schieben, A. What externally presented information do VRUs require when interacting with fully Automated Road Transport Systems in shared space? Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 118, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vissers, L.; Van der Kint, S.; Van Schagen, I.; Hagenzieker, M.P. Safe interaction between cyclists, pedestrians and automated vehicles. What do we know and what do we need to know? Hague SWOV Inst. Road Saf. Res. 2016, 46, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Guéguen, N.; Meineri, S.; Eyssartier, C. A pedestrian’s stare and drivers’ stopping behavior: A field experiment at the pedestrian crossing. Saf. Sci. 2015, 75, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, V.M.; Habibovic, A.; Andersson, J.; Lagström, T.; Nilsson, M.; Sirkka, A.; Fagerlönn, J.; Fredriksson, R.; Edgren, C.; Krupenia, S.; et al. Will there be new communication needs when introducing automated vehicles to the urban context? In Advances in Human Aspects of Transportation; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2017; p. 786. [Google Scholar]

- Tafidis, P.; Pirdavani, A.; Brijs, T.; Farah, H. Can automated vehicles improve cyclist safety in urban areas? Safety 2019, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, R.; Nordhoff, S.; Fox, C.; Amini, R.E.; Louw, T.; Wilbrink, M.; Schieben, A.; Merat, N. Understanding Interactions between Automated Road Transport Systems and Other Road Users: A Video Analysis. Available online: https://scihub.wikicn.top/10.1016/j.trf.2019.09.006 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Bjørnskau, T.; De Ceunynck, T.; Fyhri, A.; Hagenzieker, M.; Ivina, D.; Johansson, O.J.; Laureshyn, A. Cyclists interacting with self-driving buses–hypotheses and empirical findings in real traffic. In Proceedings of the International Cycling Safety Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 18–20 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Palmeiro, A.; van der Kint, S.; Hagenzieker, M.P.; van Schagen, I.N.L.G.; de Winter, J.C.F. Interactions between cyclists and automated vehicles: Results of an international photo-based survey. In Proceedings of the 7th International Cycling Safety Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 10–11 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vlakveld, W.; Van der Kint, S.; Hagenzieker, M. Cyclists’ intentions to yield for automated cars at intersections when they have right of way: Results of an experiment using high-quality video animations. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 71, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, G.; Johnston, L.; Richardson, M. An investigation of road crossing in a virtual environment. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2003, 35, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, T.A.; Rucklidge, J.J.; Owen, D. Road-Crossing Safety in Virtual Reality: A Comparison of Adolescents with and Without ADHD. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2006, 35, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plumert, J.M.; Kearney, J.; Cremer, J.F. Children’s Perception of Gap Affordances: Bicycling Across Traffic-Filled Intersections in an Immersive Virtual Environment. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb, S.; Carruth, D.W.; Sween, R.; Strawderman, L.J.; Garrison, T.M. Efficacy of virtual reality in pedestrian safety research. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 65, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CROW. Available online: https://www.crow.nl/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- KiM. Mobiliteitsbeeld. 2016. Available online: https://www.kenniscentrumsportenbewegen.nl/kennisbank/publicaties/?mobiliteitsbeeld-2016&kb_id=21518 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Waymo. On the Road. 2018. Available online: https://waymo.com/ontheroad/ (accessed on 27 September 2018).

- Bernhoft, I.M.; Carstensen, G. Preferences and behaviour of pedestrians and cyclists by age and gender. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiroz, Y.; Onelcin, P.; Alver, Y. Illegal road crossing behavior of pedestrians at overpass locations: Factors affecting gap acceptance, crossing times and overpass use. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 80, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granié, M.-A.; Pannetier, M.; Guého, L. Developing a self-reporting method to measure pedestrian behaviors at all ages. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 50, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, J.P.N.; Farah, H.; Van Arem, B.; Hagenzieker, M.P. Studying pedestrians’ crossing behavior when interacting with automated vehicles using virtual reality. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 66, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payre, W.; Cestac, J.; Delhomme, P. Fully automated driving: Impact of trust and practice on manual control recovery. Hum. Factors 2015, 58, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witmer, B.G.; Jerome, C.J.; Singer, M.J. The factor structure of the presence questionnaire. Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2005, 14, 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, J.E.; Bles, W.; Groen, E.L. A theory on visually induced motion sickness. Displays 2008, 29, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubeck, A.J.A.; Bos, J.E.; Stins, J.F. Motion in images is essential to cause motion sickness symptoms, but not to increase postural sway. Displays 2015, 38, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Emmerik, M.L.; De Vries, S.C.; Bos, J.E. Internal and external fields of view affect cybersickness. Displays 2011, 32, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Horrey, W.J.; Yu, R. The effect of conformity tendency on pedestrians’ road-crossing intentions in China: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2009, 41, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund Research Ltd. Repeated Measures ANOVA. 2018. Available online: https://statistics.laerd.com/statistical-guides/repeated-measures-anova-statistical-guide.php (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Kincaid, C. Guidelines for Selecting the Covariance Structure in Mixed Model Analysis. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis. 2005, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings/proceedings/sugi30/198-30.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Singer, J.D. Using SAS PROC MIXED to Fit Multilevel Models, Hierarchical Models, and Individual Growth Models. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 1998, 23, 323–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxley, J.; Ihsen, E.; Fildes, B.N.; Charlton, J.L.; Day, R.H. Crossing roads safely: An experimental study of age differences in gap selection by pedestrians. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2005, 37, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Cohen, P.; Chen, S. How Big is a Big Odds Ratio? Interpreting the Magnitudes of Odds Ratios in Epidemiological Studies. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2010, 39, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeiro, A.R.; Van Der Kint, S.; Vissers, L.; Farah, H.; De Winter, J.; Hagenzieker, M.P. Interaction between pedestrians and automated vehicles: A Wizard of Oz experiment. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 58, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Levels | Annotation | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle type | 2 | AV | Automated Vehicle |

| CV | Conventional Vehicle | ||

| Vehicle speed | 2 | 20 | Vehicle driving speed 20 km/h |

| 30 | Vehicle driving speed 30 km/h | ||

| Gap size | 2 | Small Gap (SG) | Gap between vehicle and cyclist was 0.5 s/2.8 m (V = 20)/4.2 m (V = 30) |

| Large Gap (LG) | Gap between vehicle and cyclist was 2 s/11.1 m (V = 20)/16.7 m (V = 30) | ||

| Priority to the cyclist | 2 | Yes | Cyclist had priority over the vehicle |

| No | Vehicle had priority over the cyclist |

| Fixed Coefficients | Β (SE) | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slow down | ||||

| Intercept | −0.74(2.22) | 0.48 | [0.01,37.50] | 0.73 |

| Vehicle type (1 = CV, 2 * = AV) | −0.19(0.19) | 0.83 | [0.57,1.21] | 0.33 |

| Gap distance (meters; 1 = 2.8 m, 4 * = 16.7 m) | 2.36(0.21) | 10.55 | [7.03,15.85] | <0.001 |

| Gap distance (meters; 2 = 4.2 m, 4 * = 16.7 m) | 2.39(0.20) | 10.92 | [7.31,16.31] | <0.001 |

| Gap distance (meters; 3 = 11.1 m, 4 * = 16.7 m) | 0.10(0.21) | 1.01 | [0.73,1.65] | 0.65 |

| Priority to cyclist (1 = yes, 2 * = no) | −2.03(0.15) | 0.13 | [0.10,0.17] | <0.001 |

| Risk group (1 = low, 2 * = high) | 0.56(0.15) | 1.76 | [1.31,2.37] | <0.001 |

| Stated Trust (1 = More, 3 * = No difference) | −0.30(0.32) | 0.74 | [0.40,1.38] | 0.34 |

| Stated Trust (2 = Less, 3 * = No difference) | −0.10(0.23) | 0.91 | [0.58,1.42] | 0.67 |

| Vehicle * Stated Trust (CV * More) | 0.76(0.44) | 2.14 | [0.90,5.10] | 0.09 |

| Vehicle * Stated Trust (CV * Less) | −0.75(0.33) | 0.47 | [0.25,0.90] | 0.02 |

| Cycle faster | ||||

| Intercept | −0.23(2.22) | 0.74 | [0.01,62.14] | 0.92 |

| Vehicle type (1 = CV, 2 * = AV) | 0.26(0.19) | 1.29 | [0.89,1.88] | 0.18 |

| Gap distance (meters; 1 = 2.8m, 4 * = 16.7 m) | 1.05(0.20) | 2.86 | [1.91,4.27] | <0.001 |

| Gap distance (meters; 2 = 4.2 m, 4 * = 16.7 m) | 0.31(0.21) | 1.36 | [0.91,2.04] | 0.14 |

| Gap distance (meters; 3 = 11.1 m, 4 * = 16.7 m) | 0.02(0.20) | 1.02 | [0.69,1.50] | 0.93 |

| Priority to cyclist (1 = yes, 2 * = no) | −0.99(0.15) | 0.37 | [0.28,0.50] | <0.001 |

| Risk group (1 = low, 2 * = high) | 0.30(0.15) | 1.35 | [1.00,1.81] | 0.05 |

| Stated Trust (1 = More, 3 * = No difference) | −0.44(0.32) | 0.65 | [0.34,1.21] | 0.17 |

| Stated Trust (2 = Less, 3 * = No difference) | −0.13(0.23) | 0.88 | [0.56,1.39] | 0.59 |

| Vehicle * Stated Trust (CV * More) | −0.10(0.45) | 0.90 | [0.37,2.18] | 0.82 |

| Vehicle * Stated Trust (CV * Less) | −0.56(0.33) | 0.57 | [0.30,1.08] | 0.08 |

| Session 1 | Session 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV | CV | AV | CV | |

| PBC | 5.2 (SD = 1.0) | 4.8 (SD = 1.2) | 5.0 (SD = 1.1) | 5.2 (SD = 1.3) |

| PR | 5.0 (SD = 1.1) | 4.2 (SD = 1.0) | 4.7 (SD = 1.2) | 5.0 (SD = 1.2) |

| Model | −2 LL | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full model (Table 2) | 10970.2 | 10974.2 | 10984.8 |

| Session 1 model (Table 4) | 4095.7 | 4099.8 | 4108.3 |

| Session 2 model (Table 5) | 5407.7 | 5411.7 | 5420.9 |

| Fixed Coefficients | Session 1 | Session 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Slow down | ||||

| Intercept | 12.31 | [0.10,1578.9] | 3.82 | [0.04,349.3] |

| Vehicle type (1 = AV, 2 + = CV) | 0.64 | [0.35,1.17] | 1.00 | [0.59,1.70] |

| Gap distance (meters; 1 = 2.8 m, 4 + = 16.7 m) | 8.35 *** | [4.27,16.34] | 13.32 *** | [7.50,23.67] |

| Gap distance (meters; 2 = 4.2 m, 4 + = 16.7 m) | 10.40 *** | [5.34,20.22] | 12.77 *** | [7.26,22.45] |

| Gap distance (meters; 3 = 11.1 m, 4 + = 16.7 m) | 1.07 | [0.54,2.11] | 1.11 | [0.63,1.97] |

| Priority to cyclist (1 = yes, 2 + = no) | 0.16 *** | [0.10,0.25] | 0.11 *** | [0.08,0.17] |

| Risk group(1 = low, 2 + = high) | 1.46 | [0.84,2.55] | 1.66 * | [1.07,2.60] |

| Stated Trust AV as compared to CV(1 = More, 3 + = No difference) | 0.66 | [0.23,1.89] | 0.39 | [0.15,1.01] |

| Stated Trust AV as compared to CV(2 = Less, 3 + = No difference) | 0.50 | [0.22,1.10] | 0.77 | [0.36,1.68] |

| Knowledge AVs | 0.77 * | [0.62,0.95] | 1.03 | [0.86,1.23] |

| PBC CV | 0.73 * | [0.53,1.00] | 0.79 | [0.56,1.11] |

| PR CV | 1.11 | [0.78,1.57] | 0.89 | [0.65,1.24] |

| PBC AV | 0.87 | [0.57,1.35] | 1.69 * | [1.11,2.58] |

| PR AV | 1.00 | [0.69,1.46] | 0.54 *** | [0.39,0.75] |

| Vehicle * Stated Trust(CV * More) | 2.26 | [0.69,8.86] | 2.09 | [0.62,7.11] |

| Vehicle * Stated Trust(CV * Less) | 1.32 | [0.44,3.98] | 0.31 * | [0.13,0.78] |

| Cycle faster | ||||

| Intercept | 23.66 | [0.18,3050.2] | 3.72 | [0.04,337.0] |

| Vehicle type (1 = AV, 2 + = CV) | 1.34 | [0.73,2.47] | 1.28 | [0.75,2.19] |

| Gap distance (meters; 1 = 2.8 m, 4 + = 16.7 m) | 1.44 | [0.74,2.80] | 4.84 *** | [2.74,8.54] |

| Gap distance (meters; 2 = 4.2 m, 4 + = 16.7 m) | 0.97 | [0.50,1.90] | 1.75 | [0.98,3.11] |

| Gap distance (meters; 3 = 11.1 m, 4 + = 16.7 m) | 0.95 | [0.51,1.80] | 1.12 | [0.65,1.93] |

| Priority to cyclist (1 = yes, 2 + = no) | 0.39 *** | [0.25,0.63] | 0.37 *** | [0.25,0.56] |

| Risk group(1 = low, 2 + = high) | 1.22 | [0.70,2.12] | 1.43 | [0.92,2.22] |

| Stated Trust AV as compared to CV(1 = More, 3 + = No difference) | 0.92 | [0.32,2.61] | 0.24 ** | [0.09,0.62] |

| Stated Trust AV as compared to CV(2 = Less, 3 + = No difference) | 0.61 | [0.27,1.36] | 0.84 | [0.38,1.83] |

| Knowledge AVs | 0.88 | [0.71,1.09] | 1.02 | [0.85,1.22] |

| PBC CV | 0.91 | [0.66,1.25] | 0.78 | [0.55,1.10] |

| PR CV | 0.78 | [0.55,1.11] | 0.80 | [0.58,1.11] |

| PBC AV | 0.84 | [0.55,1.29] | 2.09 *** | [1.37,3.20] |

| PR AV | 0.99 | [0.68,1.45] | 0.53 *** | [0.38,0.74] |

| Vehicle * Stated Trust(CV * More) | 0.51 | [0.13,2.06] | 1.24 | [0.36,4.32] |

| Vehicle * Stated Trust(CV * Less) | 1.18 | [0.39,3.52] | 0.34 ** | [0.14,0.84] |

| Involvement | Adaptation/Immersion | Interface Quality | Total Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 4.69 | 5.20 | 2.67 | 4.47 |

| SD | 0.57 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.64 |

| MISC Baseline | MISC 1 Session 1 | MISC 2 Session 1 | MISC 1 Session 2 | MISC Final | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.47 | 1.89 | 1.85 | 1.94 | 2.26 |

| SD | 0.98 | 2.18 | 1.02 | 1.39 | 1.82 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nuñez Velasco, J.P.; de Vries, A.; Farah, H.; van Arem, B.; Hagenzieker, M.P. Cyclists’ Crossing Intentions When Interacting with Automated Vehicles: A Virtual Reality Study. Information 2021, 12, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12010007

Nuñez Velasco JP, de Vries A, Farah H, van Arem B, Hagenzieker MP. Cyclists’ Crossing Intentions When Interacting with Automated Vehicles: A Virtual Reality Study. Information. 2021; 12(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleNuñez Velasco, Juan Pablo, Anouk de Vries, Haneen Farah, Bart van Arem, and Marjan P. Hagenzieker. 2021. "Cyclists’ Crossing Intentions When Interacting with Automated Vehicles: A Virtual Reality Study" Information 12, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12010007

APA StyleNuñez Velasco, J. P., de Vries, A., Farah, H., van Arem, B., & Hagenzieker, M. P. (2021). Cyclists’ Crossing Intentions When Interacting with Automated Vehicles: A Virtual Reality Study. Information, 12(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12010007