Green Purchase Behavior in Indonesia: Examining the Role of Knowledge, Trust and Marketing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.2.1. Environmental Knowledge (EK)

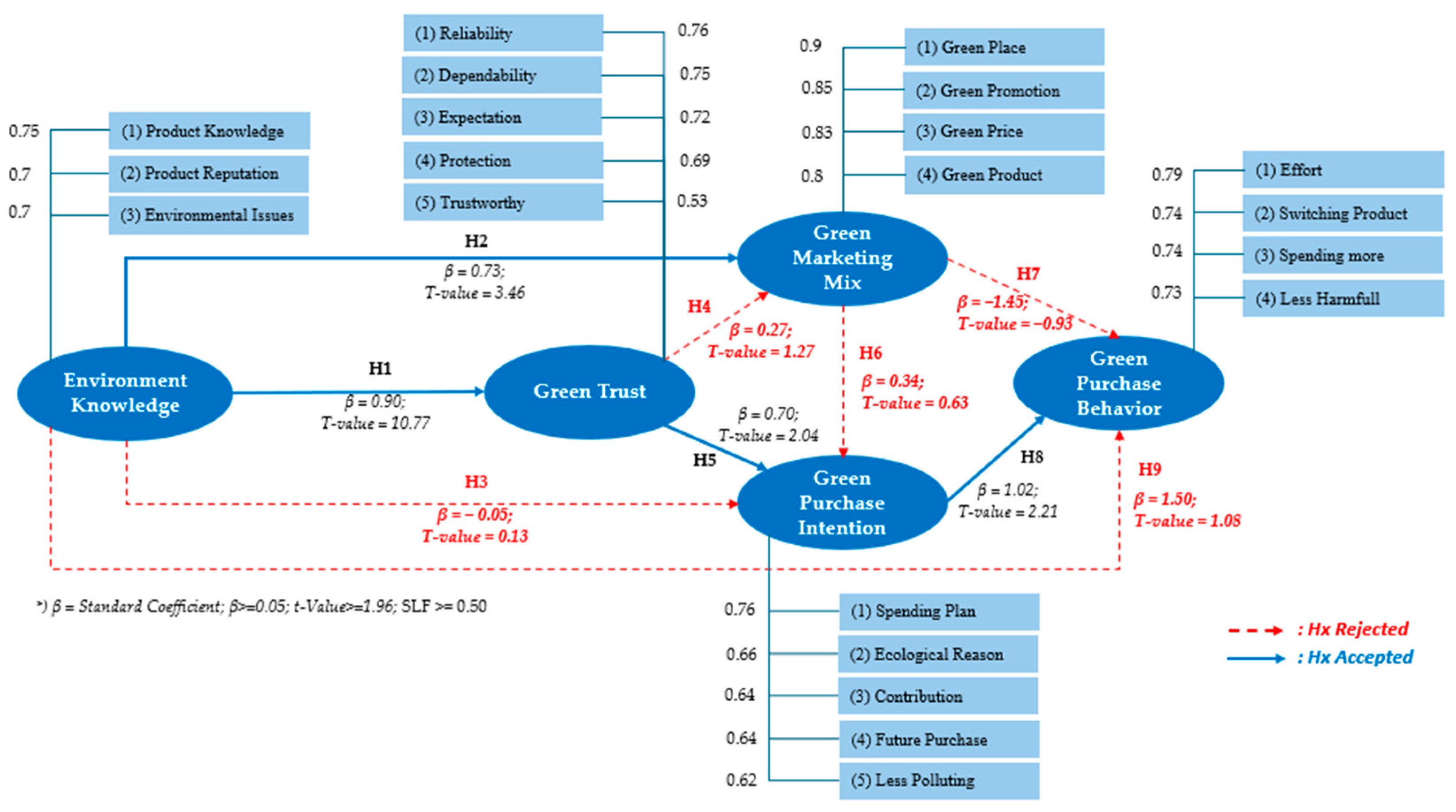

- H1: Environmental knowledge positively influences green trust.

- H2: Environmental knowledge positively influences the green marketing mix.

- H3: Environmental knowledge positively influences green purchase intention.

2.2.2. Green Trust (GT)

- H4: Green trust positively influences the green marketing mix.

- H5: Green trust positively influences green purchase intention.

2.2.3. Green Marketing Mix (GMM)

- H6: The green marketing mix positively influences green purchase intention.

- H7: The green marketing mix positively influences green purchase behavior.

2.2.4. Green Purchase Intention (GPI)

- H8: Green purchase intention positively influences green purchase behavior.

2.2.5. Green Purchase Behavior (GPB)

- H9: Environmental knowledge positively influences green purchase behavior.

2.3. Research Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Instrumentation

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Ethical Consideration

4. Results

4.1. Samples and Data Collection Procedures

4.2. Data Screening and Data Analysis

4.3. Demographic Profile

4.4. Normality, Collinearity, Homogeneity, and Reliability

- Normality: The Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests showed non-normality (p < 0.05), confirming the need for non-parametric or robust analytical methods.

- Collinearity: Spearman’s correlation and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) results showed no multicollinearity; all values were below the 0.85 threshold.

- Homogeneity: Levene’s test indicated unequal variances in expenditure level (GPI, p = 0.025) and residence (GMM, p = 0.014), suggesting socio-economic influence on these variables.

- Reliability: Cronbach’s alpha values exceeded 0.70 for all constructs (ENK, GTR, GMM, GPI, GPB), confirming acceptable internal consistency [158].

4.5. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.6. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Analysis

4.6.1. Measurement Model Analysis

4.6.2. Overall Measurement Model

4.6.3. Structural Equation Model (SEM) Analysis

4.7. Summary of Hypotheses

5. Discussion

5.1. Demograpic Profile

5.2. Accepted Hypotheses

5.3. Rejected Hypotheses

5.3.1. Environmental Knowledge Requires Mediation

5.3.2. Trust Does Not Shape Green Marketing Strategy

5.3.3. Green Marketing Mix Alone Is Insufficient

5.4. Research Contributions

5.4.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.4.2. Managerial Contributions

- Trust building is essential: Firms should increase transparency in sustainability claims through the use of third-party certifications, credible eco-labels, and clear communication of environmental benefits to reinforce green trust and reduce skepticism.

- Consumer education: Targeted awareness campaigns can enhance environmental knowledge, thereby indirectly boosting purchase intention through heightened trust.

- Affordability as a critical enabler: Given that price is the most influential element of the green marketing mix, firms and governments must address the trust–affordability gap through the following:

- Tax incentives or subsidies for sustainable products [201].

- Value-based pricing strategies that emphasize long-term savings.

- Loyalty programs and cost reduction innovations such as eco-friendly packaging or localized production.

- Targeted marketing strategies: Promotions should integrate TPB elements, including subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, to reduce the intention–behavior gap. Strategies might include the following:

- Leveraging social influence via green endorsements and peer recommendations [202].

- Designing green products that fit seamlessly into consumers’ existing routines and lifestyle preferences.

- Enable supportive ecosystems: Policymakers should complement firm-level efforts by creating enabling environments through public awareness campaigns, CSR-linked tax reliefs and infrastructure investments that facilitate sustainable consumption (e.g., green logistics, accessible eco-products).

5.5. Research Limitations

5.6. Suggestions for Future Research

- Broaden Geographic and Cultural Scope: Future studies should investigate green consumer behavior across diverse Indonesian regions, particularly rural areas, to capture socio-economic and cultural variability. Cross-national comparisons between emerging and developed economies may further contextualize behavioral determinants [203].

- Examine Mediators and Moderators: The indirect relationship between environmental knowledge (ENK) and green purchase behavior (GPB) calls for the inclusion of mediators such as environmental concern or perceived consumer effectiveness. Moderators like income, education, and environmental literacy may clarify boundary conditions for behavioral activation [204,205].

- Apply Longitudinal and Experimental Designs: To observe behavioral change over time, researchers should adopt longitudinal methods. Experimental approaches, such as A/B testing or simulated shopping scenarios, can establish causal links between interventions (e.g., pricing, labeling) and outcomes [202,203].

- Deconstruct the Green Marketing Mix (GMM): Given GMM’s non-significant direct effects, future research should analyze individual elements (product, price, place, promotion) to determine their relative influence across consumer segments and contexts.

- Explore Dimensions of Trust: As green trust (GTR) significantly mediates green behavior, future studies should distinguish between institutional, brand, and product trust. Understanding how trust is built, through certifications, CSR, or peer reviews—can inform both practice and policy [204].

- Incorporate Identity and Lifestyle Factors: Further investigation into eco-identity, values congruence, and lifestyle fit may uncover more nuanced predictors of green consumption. Segmenting consumers by eco-lifestyle profiles could improve targeting effectiveness.

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Measured Variable | Scale | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soppping Experience: Have you ever shopped organic food product at a supermarket or hypermarket? | Yes No | 0 1 | Filters respondents to ensure they have lifetime experience purchasing organic food at a supermarket or hypermarket. If respondents don’t have the shopping experience, they cannot access the next questions. |

| Area/Region: In which area/region of Jabodetabek do you live in Indonesia? | Jakarta | 0 | Filters respondents to ensure they are from the defined study region. If respondents live outside the Jabodetabek area in Indonesia, they cannot access the next questions. This question helps the researcher track the unit of analysis. |

| Bogor | 1 | ||

| Depok | 2 | ||

| Tangerang | 3 | ||

| Bekasi | 4 | ||

| Others | 5 | ||

| Gender | Male | 0 | Explores differences in green purchasing behavior by gender. |

| Female | 1 | ||

| Others | 2 | ||

| Age | 18–24 | 0 | Examines the relationship between age and the research model variables. |

| 25–35 | 1 | ||

| 36–45 | 2 | ||

| 46–55 | 3 | ||

| 55 and more | 4 | ||

| Total household Expenditure Rate per Month | ≥Rp7,500,000 | 0 | Assesses whether household expenditure influences green product purchasing behavior. |

| Rp5,000,001–Rp7,500,000 | 1 | ||

| Rp3,000,000–Rp5,000,000 | 2 | ||

| Rp2,000,001–Rp3,000,000 | 3 | ||

| Rp1,500,001–Rp2,000,000 | 4 | ||

| Rp1,000,001–Rp1,500,000 | 5 | ||

| ≤Rp1,000,000 | 6 | ||

| Education Level | Postgraduated (Master/Doctoral) | 0 | Evaluates the influence of educational background on green purchasing behavior. |

| Graduated (Bachelor) | 1 | ||

| Secondary (High School) | 2 | ||

| Vocational and less | 3 | ||

| Place of Living | Village (Rural Area) | 0 | Investigates whether place of residence affects green behavior as a daily lifestyle factor. |

| Town (Suburban Area) | 1 | ||

| City (Urban Area) | 2 |

| Latent Variable | Code | Measurement | No. of Item |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Knowledge (ENK) | ENK1–ENK3 | ENK1: I can tell if the appliances I bought are good for the environment ENK2: I know more about recycling than other ordinary people ENK3: I thoroughly know about environmental issues | 3 |

| Green Trust (GTR) | GTR1–GTR5 | GTR1: I feel that organic food product environmental commitments are generally reliable GTR2: I feel that organic food product environmental performance is generally dependable GTR3: I feel that organic food product environmental argument is generally trustworthy GTR4: Organic food product environmental concern meets my expectations GTR5: Organic food product keeps promises and commitments for environmental protection | 5 |

| Green Marketing Mix (GMM) | GPO1–GPO4 | Green Product (GPO) GPO1: Green product companies focus on manufacturing products that have the lowest rate of negative human reflection. GPO2: Green product companies contribute to producing green products with less pollution. GPO3: There is an effective control on green products that green product companies produce. GPO4: Green product companies make products free of strong toxic materials. | 16 |

| GPR1–GPR4 | Green Price (GPR) GPR1: Green product companies raise the prices of their products, which negatively affects the environment that happens due to misusage. GPR2: Increased prices of green products sometimes stop me from purchasing them. GPR3: The price difference between green products and conventional products is large. GPR4: Green products have a price that is proportional to their quality | ||

| GPL1–GPL4 | Green Place (GPL) GPL1: Environmentally friendly products are sold at reputable agents GPL2: Green product companies make delivery easy. GPL3: Green products companies aim to work with environmentally friendly agents. GPL4: The stores of green product companies are clean. | ||

| GPM1–GPM4 | Green Promotion (GPM) GPM1: Green product companies devote a special day to the environment. GPM2: Green product companies favor hosting environmental activities, festivities, seminars, and conferences. GPM3: Employees of green products companies advise customers on how to use their products not to harm the environment GPM4: Green product companies contribute to supporting environmental centers. | ||

| Green Purchase Intention (GPI) | GPI1–GPI5 | GPI1: I will consider buying green products as they are less polluting in the near future/in coming times GPI2: I will consider switching to green product brands for ecological reasons GPI3: I aim/plan to pay out/to spend more on green product rather than conventional product GPI4: I expect to purchase product in the future because of its positive environmental contribution GPI5: I certainly want to buy green products in coming future | 5 |

| Green Purchase Behavior (GPB) | GPB1–GPB4 | GPB1: I try to buy green product. GPB2: I have switched to buy green products because of the environmental benefits. GPB3: When I choose between the same type of products, I purchase the ones that are less harmful to the environment. GPB4: I buy green products even if they are more expensive than nongreen ones | 4 |

| Total Item | 33 |

References

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Roser, M.; Ritchie, H.; Ortiz-Ospina, E. Population Growth. Our World in Data. 2019. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Tietenberg, T.; Lewis, L. Environmental and Natural Resource Economics: A Contemporary Approach, 10th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo, M.; Gasparatos, A. Corporate environmental sustainability in the retail sector: Drivers, strategies and performance measurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y. Green marketing and consumer purchasing behavior in the retail sector: A study of green products. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 27, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerke, M.; Weitkamp, M.; Bosse, D. Ethical consumption: Understanding consumer behavior towards sustainable products. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Joost, G.; Basso, M. Green consumption behavior in the retail industry: Understanding consumer choices and preferences for sustainable products. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, S.; Smith, A.; Naughton, B. The changing landscape of consumer behavior: An analysis of the rise of green products. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 42, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, D. Green products and consumer choice: The role of environmental performance and resource efficiency. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2120–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, A.; Catană, S.-A.; Deselnicu, D.C.; Cioca, L.-I.; Ioanid, A. Factors influencing consumer behavior toward green products: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, M.S.; Cheok, M.Y.; Alenezi, H. Assessing the Impact of Green Consumption Behavior and Green Purchase Intention among Millennials toward Sustainable Environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 23335–23347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, I.; Jayasinghe, U.; Perera, R. Green consumption and consumer behaviors toward environmental protection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G. The influence of green marketing on consumers’ purchase intentions: An empirical study in India. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Green products: An exploratory study on the consumer behavior in emerging economies of the East. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F.; Chai, L.T. Attitude toward the environment and green products: Consumer perspective. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2010, 4, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlau, W.; Hirsch, D. Sustainable consumption and the attitude-behaviour-gap phenomenon—Causes and measurements towards sustainable development. Int. J. Food Syst. Dynamics 2015, 6, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ghodeswar, B.M. Factors affecting consumers’ green purchase behavior: A study in the Indian context. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; SSSP Springer Series in Social Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.H.; Chang, C.H.; Yansritakul, C. Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isac, N.; Javed, A.; Radulescu, M.; Cismasu, I.D.L.; Yousaf, Z.; Serbu, R.S. Is greenwashing impacting on green brand trust and purchase intentions? Mediating role of environmental knowledge. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 12345–12367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. How to regain green consumer trust after greenwashing: Experimental Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hwang, H.; Choi, S.M. The effects of green trust on consumer eco-friendly product purchasing intention. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, N.; Makris, I.; Deirmentzoglou, G.A.; Apostolopoulos, S. The Impact of Greenwashing Awareness and Green Perceived Benefits on Green Purchase Propensity: The Mediating Role of Green Consumer Confusion. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saren, M. Marketing theory. Marketing Theory: A Student Text, 2nd ed.; Baker, M., Saren, M., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2010; pp. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Ghodeswar, B.M. Green marketing mix: A review of literature and direction for future research. Int. J. Appl. Bus. Int. Manag. 2015, 6, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, J.A. The New Rules of Green Marketing: Strategies, Tools, and Inspiration for Sustainable Branding; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Govender, J.P.; Govender, T.L. The influence of green marketing on consumer purchase behavior. Environ. Econ. 2016, 7, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasika, I.B.M.; Friedlingstein, P.; Sitch, S.; O’Sullivan, M.; Duran-Rojas, M.C.; Rosan, T.M.; Goldewijk, K.K.; Pongratz, J.; Schwingshackl, C.; Chini, L.P.; et al. Uncertainties in Carbon Emissions from Land Use and Land Cover Change in Indonesia. Biogeosciences 2025, 22, 3547–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MEF). Indonesia’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) Under the Paris Agreement; Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017; Available online: https://www.menlhk.go.id (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Climate Transparency. Climate Transparency Report: Indonesia. 2022. Available online: https://www.climate-transparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/CT2022-Indonesia-Web.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). Ecological Impacts of Palm Oil Expansion in Indonesia. 2016. Available online: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Indonesia-palm-oil-expansion_ICCT_july2016.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Carbon Brief. The Carbon Brief Profile: Indonesia. 2020. Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org/the-carbon-brief-profile-indonesia/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). Sustainable Consumption in Indonesia: The Role of Green Products and Organic Markets; WWF Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014; Available online: https://www.wwf.or.id (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Indonesian Organic Alliance. The Growth of Organic Food Markets in Indonesia; Indonesian Organic Alliance: Bogor, Indonesia, 2014; Available online: https://www.organic-indonesia.org (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Air Pollution in Indonesia: Health Impacts and Mitigation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www.who.int (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision; United Nations Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://population.un.org/wup (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Suhartanto, D.; Kartikasari, A.; Arsawan, I.W.E.; Suhaeni, T.; Anggraeni, T. Driving youngsters to be green: The case of plant-based food consumption in Indonesia. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Mohd Suki, N.; Najib, M.; Suhaeni, T.; Kania, R. Young Muslim consumers’ attitude towards green plastic products: The role of environmental concern, knowledge of the environment and religiosity. J. Islam. Mark. 2023, 14, 3168–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Dean, D.; Amalia, F.A.; Triyuni, N.N. Attitude formation towards green products evidence in Indonesia: Integrating environment, culture, and religion. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2024, 30, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation—Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028, Erratum in Lancet 2015, 386, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.S.; Frumkin, H. Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Making Peace with Nature: A Scientific Blueprint to Tackle the Climate, Biodiversity and Pollution Emergencies; United Nations: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/making-peace-nature (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Greenland, S. Pro-environmental purchase behaviour: The role of consumers’ biospheric values. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kim, Y.; Lee, H. Consumer behavior toward green products in the green marketing mix. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wu, Y. Green products and their environmental impacts: From production to consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The drivers of green brand equity: Green brand image, green satisfaction, and green trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Toward green trust: The influences of green perceived quality, green perceived risk, and green satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Benoît-Moreau, F.; Larceneux, F. How sustainability ratings might deter ‘greenwashing’: A closer look at ethical corporate communication. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Thyagaraj, K.S. Understanding the influence of green marketing on green purchase behavior from the perspective of Indian consumers. Int. J. Manag. Res. Bus. Strategy 2015, 4, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Ghodeswar, B.M. Factors affecting consumers’ green product purchase decisions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnawas, I.; Altarifi, S. Exploring the role of brand trust and brand attachment in the relationship between green marketing and brand equity in the green retail context. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Yu, Z.; Umar, M.; Kumar, A.; Badii, M.H. Green marketing strategies and their role in influencing customer behavior in GCC countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Mohammed, R.; Haroon, M.S. The role of subjective norms in the theory of planned behavior in the context of green purchase intention: A meta-analytic path analysis. J. Bus. Retail Manag. Res. 2014, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Setyowati, D.L.; Sukoco, B.M. Urban green purchase behavior: The role of environmental knowledge and attitudes in Jakarta. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, R.N.; Hati, S.R.H. Investigating green purchase behavior in Jakarta: An application of TPB model. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2020, 11, 1447–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Crane, A. Green Marketing: Legend, Myth, Farce or Prophesy? Qual. Mark. Res. 2005, 8, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Coudounaris, D.N.; Hultman, M. Drivers and Outcomes of Green Marketing Performance: A Conceptual Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, M.C. Two avenues for encouraging conservation behaviors. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2003, 10, 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.F.; Chang, C.H. The moderating role of environmental concern in the relationship between green marketing and consumer trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, D.; Wünderlich, N.V.; Hutter, K. When does sustainability drive consumer behavior? The role of consumers’ personal values. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, L.; Gielens, K.; De Vries, F. The impact of environmental claims on consumer trust and purchase intentions: The moderating role of consumers’ environmental awareness. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 551–565. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Zeng, Q. A study on consumer attitudes towards green products in China: Analyzing the impact of environmental concern and the role of marketing communications. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 523–529. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Green marketing and its impact on the environment: A study on consumer behavior in India. Int. J. Manag. 2015, 6, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. The effects of environmental knowledge on consumers’ pro-environmental behavior: An analysis of green purchasing intention. J. Consum. Aff. 2013, 47, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrete, L.; Del Bosque, I.R.; Garcia, J.A. Consumer environmental behavior: General vs. environmentally friendly product purchase. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaola, P.; Sieng, H.; Chia, W.L. Environmental knowledge and its effect on the green purchase intention: A case of Botswana. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 8, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmat, M.; Santosa, P.I. The influence of eco-label and green advertising on green purchase behavior in Greater Jakarta. Indones. J. Sustain. Account. Manag. 2021, 5, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, R.F.; Oktaviani, R.; Andriani, L.; Amrina, E. Determinants of Indonesian millennials’ intention to buy eco-friendly products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsyah, D.P.; Othman, N.; Bakri, M.H. Green lifestyle among Indonesian consumers: The role of environmental knowledge and awareness. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 16636–16658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S. Greenwashing: A study of the environmental claims in corporate social responsibility reports. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufidah, I.; Djajadikerta, H.G.; Zhang, J. Green consumer behavior in an emerging market: The mediating role of green trust. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in India. Int. J. Res. Commer. Manag. 2011, 2, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Zeng, F. The impact of environmental concern on consumer purchase intention: The role of demography and lifestyle. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2011, 5, 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, T.O. Impact of green marketing mix on purchase intention. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2018, 5, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaola, P.; Chia, S.C.; Mohammed, A.S. The impact of the green marketing mix on consumer purchase intentions: A case study of green products. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 6, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Li, Y. Exploring the impact of the green marketing mix on environmental attitudes and purchase intentions: Moderating role of environmental knowledge in China’s emerging markets. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; del Bosque, I.R. Green marketing and its influence on consumer purchase intentions: The case of Spain. Sustainability 2013, 5, 1344–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. The effects of green marketing on consumer purchase behavior: A focus on product innovation and eco-certifications. Sustainability 2019, 11, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Netto, S.V.; Sobral, M.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.B.; Soares, G.R.D. Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 122556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The means and end of greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Tao, L.; Li, C. The role of consumer skepticism toward green advertising in evaluating green brand credibility and purchase intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, M.A.; Tjiptono, F. Green brand image and green purchase intention among Jakarta millennials. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 2022, 29, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawati, D.; Saragih, H.S. Green marketing and its impact on green product purchasing intention in Indonesia. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Res. 2018, 16, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Thyagaraj, K.S. Understanding the influence of green marketing on consumer green purchase behavior. Int. J. Manag. Res. Rev. 2015, 5, 369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, G.; Dai, J.; Xu, Z. The role of cultural values in green purchasing intention: Empirical evidence from Chinese consumers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavosa, M.; Saputra, J.; Lee, C. Green purchase intention: The power of success in green marketing promotion. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 75, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaola, P.P.; Potiane, B.; Mokhethi, M. Environmental concern, attitude towards green products and green purchase intentions of consumers in Lesotho. Ethiop. J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 2014, 7, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. The relationship between green marketing and environmental sustainability: A comprehensive study of green marketing in emerging economies. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C. Consumer’s environmental attitudes and behavior: The influence of environmental concern, attitude towards eco-labeled products, and environmental knowledge. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, D.J.; Hogg, M.A.; White, K.M. The theory of planned behavior: Self-identity, social identity and group norms. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 43, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors affecting green purchase behaviour and future research directions. Int. Strat. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Greenland, S. Pro-environmental purchase behaviour: The role of consumers’ biospheric values, attitudes and advertising skepticism. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, M.L.; Tan, L.P. Exploring the gap between consumers’ green rhetoric and purchasing behaviour. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, B.; Sumurung, H.; Salwa, N. Influence of green innovation on consumer purchase intentions for eco-friendly products. Ris. J. Apl. Ekon. Akunt. Bisnis 2024, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Gender differences in Egyptian consumers’ green purchase behaviour: The effects of environmental knowledge, concern and attitude. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Sroufe, R.; Shahbaz, M. Industry 4.0 and the circular economy: A literature review and recommendations for future research. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2038–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatu, V.M.; Mat, N.K.N. A review of consumer environmental behaviour and purchase intention. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Tan, L.P.; Tjiptono, F.; Yang, L. Exploring consumers’ purchase intention toward green products in an emerging market: The role of consumers’ perceived readiness. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojiaku, O.C.; Nkamnebe, A.D.; Nwaizugbo, I.C. Determinants of green consumer behavior: The influence of green advertising and green brand equity. J. Manag. Sustain. 2018, 8, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.-M.; Balaji, M.S. Linking green skepticism to green purchase behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, Á.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Environmental education does not consistently translate into action: The mediating role of personal norms and contextual facilitators. J. Environ. Educ. 2013, 44, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Sharma, P. Overcoming the “knowledge–action gap”: Contextual barriers to green purchase in developing economies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. “Green Marketing”: An analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, J.M.; Baquero, C.; Gomez, M. Understanding sustainable consumer behavior in the COVID-19 era. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Isa, Z.; Fontaine, R. Post-pandemic consumer behavior: An empirical study. J. Consum. Mark. 2022, 39, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach, 7th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alharahsheh, H.H.; Pius, A. A Review of Key Paradigms: Positivism vs. Interpretivism. Glob. Acad. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 2, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bucic, T.; Harris, J.; Arli, D. Ethical consumers among the Millennials: A cross-national study. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.; Heitmeyer, J. Looking at Gen Y shopping preferences and intentions: Exploring the role of experience and apparel involvement. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdust, L. Green consumer behavior in Indonesia: An analysis of the factors influencing the purchase of green products. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 180, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPS–Statistics Indonesia. Demographic Statistics Indonesia: Results of Population Census 2020; BPS–Statistics Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2025; Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2025/01/31/29a40174e02f20a7a31b5bc3/demographic-statistics-indonesia--results-of-population-census-2020-.html (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Slamet, A.; Haryono, T.; Wibowo, A. Environmental awareness and green consumption behavior in Indonesia: A case study of Jabodetabek. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haryono, S.; Wardoyo, P. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for Management Research with AMOS; BPFE-Yogyakarta: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Singgih, M.L. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts and Applications with AMOS; Graha Ilmu: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, L. Understanding consumer behavior towards green products: A review of literature. J. Sustain. Mark. 2020, 6, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Bohlen, G.M. Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Liu, C.; Kim, S. Environmentally sustainable textile and apparel consumption: The role of consumer knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness and perceived personal relevance. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. A hierarchical analysis of the green purchasing behavior of Egyptian consumers. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2007, 19, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.-C. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior model to investigate purchase intention of green products among Thai consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalanon, P.; Chen, J.-S.; Le, T.-T.-Y. “Why do we buy green products?” An extended theory of the planned behavior model for green product purchase behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, J.; Pachero, M. Green consumer behavior in the organic food sector: The role of trust. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Augusto, J.A.; Garrido-Lecca-Vera, C.; Lodeiros-Zubiria, M.L.; Mauricio-Andia, M. Green marketing: Drivers in the process of buying green products—The role of green satisfaction, green trust, green WOM and green perceived value. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, L.; Kuźniar, W. Green purchase behaviour gap: The effect of past behaviour on green food product purchase intentions among individual consumers. Foods 2024, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munamba, X.; Nuangjamnong, Y. The impact of green marketing mix and attitude towards the green purchase intention among generation Y consumers in Bangkok. SSRN Electron. J. 2021, 3968444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kim, D. The effect of green marketing mix on outdoor brand attitude and loyalty: A bifactor structural model approach with a moderator of outdoor involvement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Liu, Y.; Aduldecha, S.; Junaidi, J. Leveraging customer green behavior toward green marketing mix and electronic word-of-mouth. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Deng, T. Research on the green purchase intentions from the perspective of product knowledge. Sustainability 2016, 8, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, E.; Sousa, S.; Viseu, C.; Larguinho, M. Analysing the influence of green marketing communication in consumers’ green purchase behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzog, M.A. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res. Nurs. Health 2008, 31, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johanson, G.A.; Brooks, G.P. Initial scale development: Sample size for pilot studies. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010, 70, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Maidenhead, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- British Psychological Society (BPS). Ethics Guidelines for Internet-Mediated Research; British Psychological Society: Leicester, UK, 2021; Available online: https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsrep.2021.rep155 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Available online: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394260645 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Yan, Q.; Chen, J.; De Strycker, L. An outlier detection method based on mahalanobis distance for source localization. Sensors 2018, 18, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPS–Statistics Indonesia. Consumption Expenditure of Population of Indonesia March 2020; BPS–Statistics Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020; Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/en/publication/2020/11/02/2d7c91e53ab840a301689f34/pengeluaran-untuk-konsumsi-penduduk-indonesia-maret-2020.html (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- BPS–Statistics Indonesia. Consumption Expenditure of Population of Indonesia March 2022; BPS–Statistics Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2022; Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/en/publication/2022/10/20/b9e45d7c9aeb2112005aaf53/pengeluaran-untuk-konsumsi-penduduk-indonesia-maret-2022.html (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Ministry of Manpower of the Republic of Indonesia (Kemnaker). Upah Minimum Provinsi dan Upah Minimum Kabupaten/Kota (2022–2025); SatuData Kemnaker, Government of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2025; Available online: https://satudata.kemnaker.go.id (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wijanto, S.H. Structural Equation Modeling Dengan LISREL 8.8: Konsep & Tutorial; Graha Ilmu: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, F.; Sarti, S.; Frey, M. Are green consumers really green? Exploring the factors behind the actual consumption of organic food products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Consumer preferences for environmentally friendly apple production methods: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 20, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F. The drivers of consumers’ green purchasing decisions: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the value-belief-norm theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Green purchase behavior of Indian consumers: A meta-analytic study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ogden, D.T. To Buy or Not to Buy? A Social Dilemma Perspective on Green Purchasing. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, F.A.; Rennie, D. Consumer Perceptions on Organic Food. Int. Food Res. J. 2012, 19, 1277–1281. [Google Scholar]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Zielke, S. Can’t buy me green? A review of consumer perceptions of and behavior toward the price of organic food. J. Consum. Aff. 2017, 51, 211–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaoikonomou, E.; Simmers, C.; Dangelico, R.M. Consumers’ buying behavior toward organic food in greece. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2011, 24, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatu, M.K.; Mat, N.K.N. The mediating effects of green trust and perceived behavioral control on the direct determinants of intention to purchase green products in Nigeria. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkaite-Vaitonė, N.; Skackauskiene, I. How misleading marketing affects consumer green purchasing habits. Bus. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Umrani, W.A.; Khan, A.; Khan, M.M. Responsible leadership and employee’s pro-environmental behavior: The role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, A.; Lu, L. Sustainable development in the hospitality industry: A review of the literature. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Tsamakos, A.; Vrechopoulos, A.P.; Avramidis, P.K. Corporate social responsibility: Attributions, loyalty, and the mediating role of trust. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 42, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, O.; Singh, J.J.; Batista-Foguet, J.M. The role of brand experience and affective commitment in determining brand loyalty. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 18, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of consumers’ green purchase behavior in a developing nation: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Park, J.; Chi, C.G. Consequences of “Greenwashing”: Consumers’ reactions to hotels’ green initiatives. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1054–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Predicting consumer behavior for buying organic food: A cross-national study. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2019, 47, 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iovino, R.; Iraldo, F. The Circular economy and consumer behaviour: The mediating role of information seeking in buying circular packaging. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Umrani, W.A.; Khan, A.; Gul, A. The impact of perceived environmental CSR on green purchase intention: The mediating role of green trust and moderating role of green self-efficacy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Macdonnell, R.; Ellard, J. Green by choice or by necessity? The influence of situational factors on consumer preferences for green products. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 45, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Consumer buying behavior in green products: A comparison of environmental knowledge and green trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 22, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.M.; Chao, H.-F.; Lee, K.M. Understanding consumer purchase behavior for green products: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Green marketing: A critical review. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Das, D.; Tripathi, D. Examining the role of consumers’ environmental knowledge in green consumption: A comparative study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to shift consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guideline for researchers and practitioners. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Poškus, M. Environmental knowledge and attitudes toward green products: A study on lithuanian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, M.; Martinez, C. Green marketing and consumers’ attitudes towards sustainability: The role of trust and greenwashing. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G.; Opresnik, M.O.; Cunningham, P. Principles of Marketing, 17th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Janssens, W.; Van den Bergh, J.; Rayp, G. The effect of green claims on consumer’s price perceptions: A cross-national study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 45, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, K.-P.; Hennigs, N.; Behrens, S.; Klarmann, C.; Pape, J.; Thelen, M. The impact of green brand management on brand equity. J. Brand Manag. 2014, 21, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Jiménez, R.; Merle, A. The role of trust in the marketing mix: Exploring the impact of consumer trust on consumer loyalty in the digital age. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. The attitude-behavior gap in sustainable consumer behavior: A review and research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G. Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair-trade coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2018, 42, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Bohlen, G.M.; Diamantopoulos, A. The link between green purchasing decisions and measures of environmental concern. Eur. J. Mark. 1996, 30, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2011, 25, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. Green organizational identity: The influence of green marketing on consumer purchase intention. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.A.; Ibrahim, A.S. The influence of environmental knowledge on green purchase intention: The role of green trust and green marketing. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadas, K.K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M. Green marketing orientation: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasaya, M.; Li, W.; Bae, H. The role of green trust in enhancing consumer satisfaction and loyalty towards green products: Evidence from the sustainable fashion industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102297. [Google Scholar]

- Lasuin, F.; Ching, T.S. Green marketing strategies for sustainable business practices: An analysis of the theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 137, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, R.; Sayuti, A.J.; Yasa, N.N.K. Urban vs. rural consumer behavior in indonesia: The moderating role of environmental awareness in green purchase intention. J. Manaj. Kewirausahaan 2021, 23, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.B. Researching the internet: A beginner’s guide to online research. J. Res. Pract. 2005, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green purchase behavior using theory of planned behavior and environmental concern. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F.; Tung, P.J. The moderating effect of green purchase behavior on the relationship between environmental concern and green purchase intention. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1717–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boztepe, A. Green marketing and its impact on consumer buying behavior. Eur. J. Econ. Political Stud. 2012, 5, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E.; Stumpf, S.A. Green marketing strategies: An examination of stakeholders and the opportunities they present. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Wahab, H.; Diaa, N.M.; Nagaty, S.A. Demographic characteristics and consumer decision-making styles: Do they impact fashion product involvement? Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2208430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, L.S.; Środa-Murawska, S.; Smoliński, P.; Biegańska, J. Rural–urban divide: Generation Z and pro-environmental behaviour. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Z. Influencing factors of residents’ green perception under urban–rural differences: A socio-ecological model approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnan, O.; Konyalı, S. Ethical and responsible food purchasing decisions of consumers within the scope of sustainable food policies: A case study of Istanbul Province. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanjuntak, M.; Nafila, N.L.; Yuliati, L.N.; Johan, I.R.; Najib, M.; Sabri, M.F. Environmental care attitudes and intention to purchase green products: Impact of environmental knowledge, word of mouth, and green marketing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Bai, R. How does green product knowledge effectively promote green purchase intention? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, L.; Kuźniar, W. Green purchase behavior: The effectiveness of sociodemographic variables for explaining green purchases in emerging market. Sustainability 2021, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynalova, Z.; Namazova, N. Revealing consumer behavior toward green consumption. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Characteristics | Classification Standards | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 145 | 68.70% |

| Female | 65 | 30.92% | |

| Others | 1 | 0.38% | |

| Age | 18–25 | 10 | 4.96% |

| 26–35 | 67 | 31.68% | |

| 36–45 | 87 | 41.22% | |

| 46–55 | 35 | 16.41% | |

| 55 and more | 12 | 5.73% | |

| Total Household Expenditure Rate per Month | ≥Rp7,500,000 | 58 | 27.50% |

| Rp5,000,001–Rp7,500,000 | 56 | 26.70% | |

| Rp3,000,000–Rp5,000,000 | 55 | 26.00% | |

| Rp2,000,001–Rp3,000,000 | 23 | 10.70% | |

| Rp1,500,001–Rp2,000,000 | 10 | 4.60% | |

| Rp1,000,001–Rp1,500,000 | 7 | 3.40% | |

| ≤Rp1,000,000 | 2 | 1.10% | |

| Education Level | Postgraduated (Master/Doctoral) | 15 | 7.30% |

| Undergraduated (Bachelor) | 154 | 73.30% | |

| Secondary (High School) | 35 | 16.40% | |

| Vocational and less | 7 | 3.10% | |

| Place of Living | Village (Rural Area) | 7 | 3.40% |

| Town (Suburban Area) | 39 | 18.40% | |

| City (Urban Area) | 164 | 78.20% |

| Construct | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Knowledge (ENK) | 3.96 | 0.69 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 0.874 |

| Green Trust (GTR) | 3.99 | 0.61 | 1.80 | 5.00 | 0.879 |

| Green Marketing Mix (GMM) | 4.04 | 0.55 | 2.58 | 5.00 | 0.939 |

| 4.03 | 0.62 | 2.00 | 5.00 | – |

| 4.11 | 0.59 | 2.75 | 5.00 | – |

| 3.99 | 0.60 | 2.50 | 5.00 | – |

| 4.03 | 0.61 | 2.00 | 5.00 | – |

| Green Purchase Intention (GPI) | 4.01 | 0.60 | 1.80 | 5.00 | 0.869 |

| Green Purchase Behavior (GPB) | 3.97 | 0.68 | 1.50 | 5.00 | 0.901 |

| Latent Variable | Dimension | SLF * | Error | Construct Reliability | Variable Extracted | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >0.70 | >0.5 | |||||

| ENK | ENK | 0.75 | 0.50 | Reliable | ||

| ENK1 | 0.76 | 0.42 | Valid | |||

| ENK2 | 0.72 | 0.48 | Valid | |||

| ENK3 | 0.64 | 0.59 | Valid | |||

| GTR | GTR | 0.83 | 0.50 | Reliable | ||

| GT1 | 0.81 | 0.34 | Valid | |||

| GT2 | 0.74 | 0.45 | Valid | |||

| GT3 | 0.50 | 0.78 | Valid | |||

| GT4 | 0.71 | 0.51 | Valid | |||

| GT5 | 0.74 | 0.46 | Valid | |||

| GMM | GMM | 1.00 | 0.99 | Reliable | ||

| GMM.GPO | 0.92 | 0.14 | Valid | |||

| GMM.GPR | 1.00 | −0.0059 | Valid | |||

| GMM.GPL | 1.03 | −0.66 | Valid | |||

| GMM.GPM | 0.94 | 0.11 | Valid | |||

| GPI | GPI | 0.80 | 0.45 | Reliable | ||

| GPI1 | 0.65 | 0.58 | Valid | |||

| GPI2 | 0.70 | 0.51 | Valid | |||

| GPI3 | 0.65 | 0.58 | Valid | |||

| GPI4 | 0.62 | 0.62 | Valid | |||

| GPI5 | 0.72 | 0.49 | Valid | |||

| GPB | GPB | 0.85 | 0.59 | Reliable | ||

| GPB1 | 0.77 | 0.41 | Valid | |||

| GPB2 | 0.73 | 0.47 | Valid | |||

| GPB3 | 0.68 | 0.54 | Valid | |||

| GPB4 | 0.87 | 0.24 | Valid |

| GOFI | Criteria | Value | Result | GOFI | Criteria | Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCS | ≤2 | 1.05401 | Good Fit | NFI | ≥0.90 | 0.99 | Good Fit |

| p-value | >0.05 | 0.30 | Good Fit | NNFI | ≥0.90 | 1.00 | Perfect Fit |

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.016 | Good Fit | CFI | ≥0.90 | 1.00 | Perfect Fit |

| RMR | ≤0.05 | 0.040 | Good Fit | IFI | ≥0.90 | 1.00 | Perfect Fit |

| GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.90 | Good Fit | RFI | ≥0.90 | 0.98 | Good fit |

| Latent Variable | Dimension | SLF * | Error | Construct Reliability | Variable Extracted | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >0.70 | >0.5 | |||||

| ENK | ENK | 0.76 | 0.51 | Reliable | ||

| ENK1 | 0.70 | 0.51 | Valid | |||

| ENK2 | 0.75 | 0.44 | Valid | |||

| ENK3 | 0.70 | 0.51 | Valid | |||

| GTR | GTR | 0.82 | 0.49 | Reliable | ||

| GT1 | 0.77 | 0.41 | Valid | |||

| GT2 | 0.75 | 0.44 | Valid | |||

| GT3 | 0.53 | 0.72 | Valid | |||

| GT4 | 0.72 | 0.48 | Valid | |||

| GT5 | 0.69 | 0.52 | Valid | |||

| GMM | GMM | 0.90 | 0.74 | Reliable | ||

| GMM.GPO | 0.80 | 0.35 | Valid | |||

| GMM.GPR | 0.83 | 0.32 | Valid | |||

| GMM.GPL | 0.90 | 0.19 | Valid | |||

| GMM.GPM | 0.85 | 0.27 | Valid | |||

| GPI | GPI | 0.80 | 0.45 | Reliable | ||

| GPI1 | 0.62 | 0.61 | Valid | |||

| GPI2 | 0.66 | 0.56 | Valid | |||

| GPI3 | 0.76 | 0.42 | Valid | |||

| GPI4 | 0.64 | 0.59 | Valid | |||

| GPI5 | 0.64 | 0.58 | Valid | |||

| GPB | GPB | 0.84 | 0.56 | Reliable | ||

| GPB1 | 0.74 | 0.45 | Valid | |||

| GPB2 | 0.74 | 0.45 | Valid | |||

| GPB3 | 0.73 | 0.47 | Valid | |||

| GPB4 | 0.79 | 0.37 | Valid |

| GOFI | Criteria | Value | Result | GOFI | Criteria | Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCS | ≤2 | 0.93662 | Good Fit | NFI | ≥0.90 | 0.99 | Good Fit |

| p-value | >0.05 | 0.70 | Good Fit | NNFI | ≥0.90 | 1.00 | Perfect Fit |

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.000 | Perfect Fit | CFI | ≥0.90 | 1.00 | Perfect Fit |

| SRMR | ≤0.05 | 0.0140 | Good Fit | IFI | ≥0.90 | 1.00 | Perfect Fit |

| GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.88 | Marginal Fit | RFI | ≥0.90 | 0.99 | Good Fit |

| Latent Variable | Dimension | SLF * | Error | Construct Reliability | Variable Extracted | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >0.70 | >0.5 | |||||

| ENK | ENK | 0.76 | 0.51 | Reliable | ||

| ENK1 | 0.7 | 0.5 | Valid | |||

| ENK2 | 0.75 | 0.44 | Valid | |||

| ENK3 | 0.7 | 0.52 | Valid | |||

| GTR | GTR | 0.82 | 0.50 | Reliable | ||

| GT1 | 0.76 | 0.42 | Valid | |||

| GT2 | 0.75 | 0.44 | Valid | |||

| GT3 | 0.53 | 0.72 | Valid | |||

| GT4 | 0.72 | 0.48 | Valid | |||

| GT5 | 0.69 | 0.52 | Valid | |||

| GMM | GMM | 0.90 | 0.74 | Reliable | ||

| GMM.GPO | 0.8 | 0.35 | Valid | |||

| GMM.GPR | 0.83 | 0.32 | Valid | |||

| GMM.GPL | 0.9 | 0.19 | Valid | |||

| GMM.GPM | 0.85 | 0.27 | Valid | |||

| GPI | GPI | 0.80 | 0.44 | Reliable | ||

| GPI1 | 0.62 | 0.62 | Valid | |||

| GPI2 | 0.66 | 0.57 | Valid | |||

| GPI3 | 0.76 | 0.42 | Valid | |||

| GPI4 | 0.64 | 0.59 | Valid | |||

| GPI5 | 0.64 | 0.59 | Valid | |||

| GPB | GPB | 0.84 | 0.57 | Reliable | ||

| GPB1 | 0.74 | 0.45 | Valid | |||

| GPB2 | 0.74 | 0.45 | Valid | |||

| GPB3 | 0.73 | 0.4 | Valid | |||

| GPB4 | 0.79 | 0.37 | Valid |

| Hypotheses | Path | β | t-value | S.E | Margin of Error | CI (95%) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ENK → GTR | 0.90 | 10.77 | 0.0835 | 0.163 | 0.737, 1.063 | Accepted |

| H2 | ENK → GMM | 0.73 | 3.46 | 0.2107 | 0.412 | 0.318, 1.142 | Accepted |

| H3 | ENK → GPI | −0.05 | −0.13 | 0.3846 | 0.756 | −0.806, 0.706 | Rejected |

| H4 | GTR → GMM | 0.27 | 1.27 | 0.2126 | 0.416 | −0.146, 0.686 | Rejected |

| H5 | GTR → GPI | 0.70 | 2.04 | 0.3431 | 0.673 | 0.027, 1.373 | Accepted |

| H6 | GMM → GPI | 0.34 | 0.63 | 0.5397 | 1.057 | −0.718, 1.398 | Rejected |

| H7 | GMM → GPB | −1.45 | −0.93 | 1.5591 | 3.053 | −4.505, 1.605 | Rejected |

| H8 | GPI → GPB | 1.02 | 2.21 | 0.4611 | 0.904 | 0.116, 1.924 | Accepted |

| H9 | ENK → GPB | 1.50 | 1.08 | 1.3889 | 2.722 | −1.222, 4.222 | Rejected |

| No | Effects | Pathways | β Calculation | β Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE * | IE ** | DE * | IE ** | |||

| 1 | ENK → GMM | β2 | n. a | 0.73 | n. a | 0.73 |

| 2 | ENK → GTR → GPI | β3 | β1* β5 | −0.05 | 0.63 | 0.58 |

| 3 | ENK → GTR → GPI → GPB | β9 | β1* β5* β8 | 1.50 | 0.6426 | 2.1426 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vironika, P.; Maulida, M. Green Purchase Behavior in Indonesia: Examining the Role of Knowledge, Trust and Marketing. Challenges 2025, 16, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16030041

Vironika P, Maulida M. Green Purchase Behavior in Indonesia: Examining the Role of Knowledge, Trust and Marketing. Challenges. 2025; 16(3):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16030041

Chicago/Turabian StyleVironika, Philia, and Mira Maulida. 2025. "Green Purchase Behavior in Indonesia: Examining the Role of Knowledge, Trust and Marketing" Challenges 16, no. 3: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16030041

APA StyleVironika, P., & Maulida, M. (2025). Green Purchase Behavior in Indonesia: Examining the Role of Knowledge, Trust and Marketing. Challenges, 16(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16030041