Community-Based Integrated Care System for People with Mental Illness in Japan: Evaluating Location Characteristics of Group Homes to Determine the Feasibility of Daily Life Skill Training

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Target Area

2.2. Terms Used in This Study

2.2.1. Community-Based Integrated Care System for People with Mental Illness (CICSM)

2.2.2. Every-Day Living Area (ELA)

2.3. Types and Sources of Data Used for Analysis

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. GH Capacity and Geographical Distribution

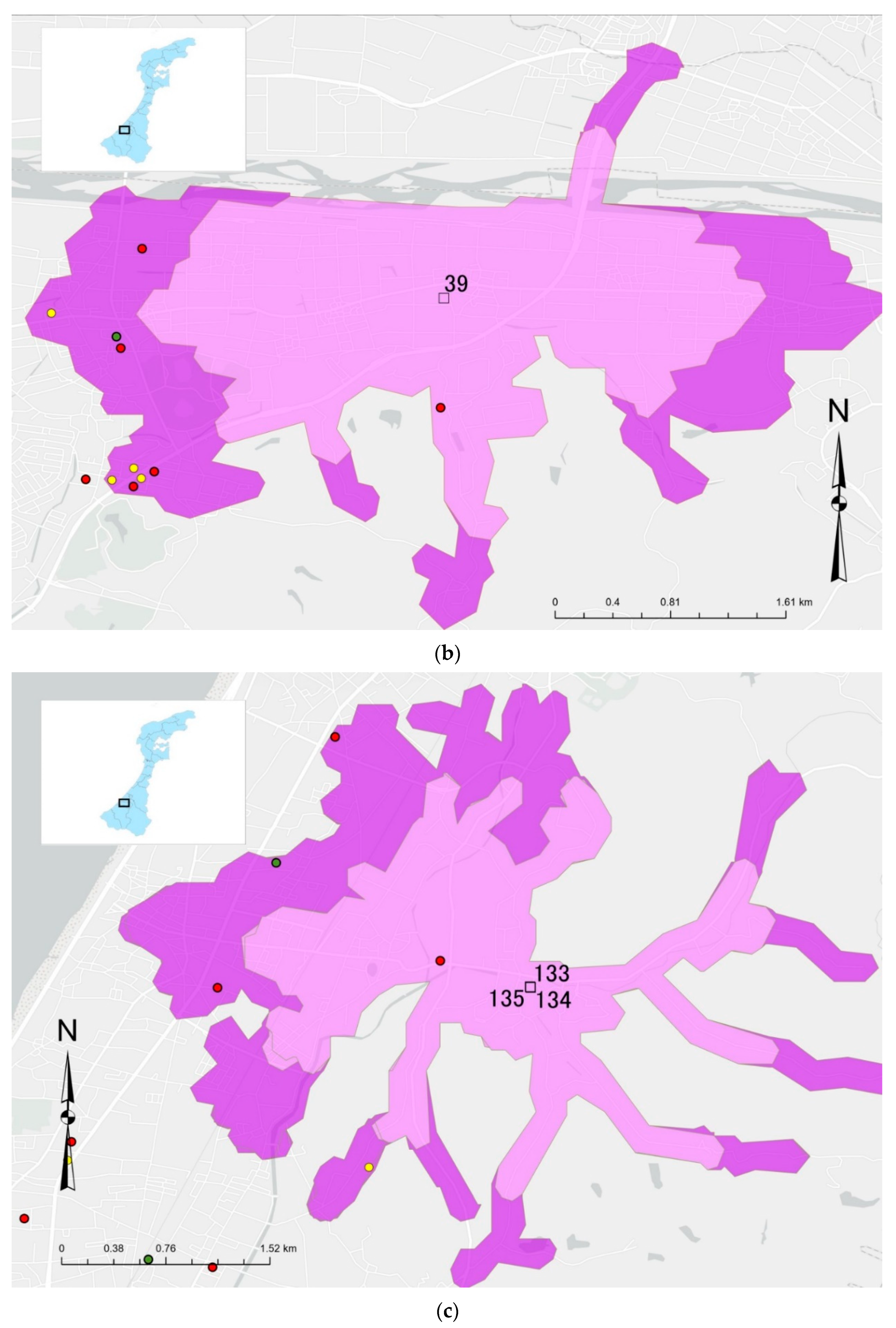

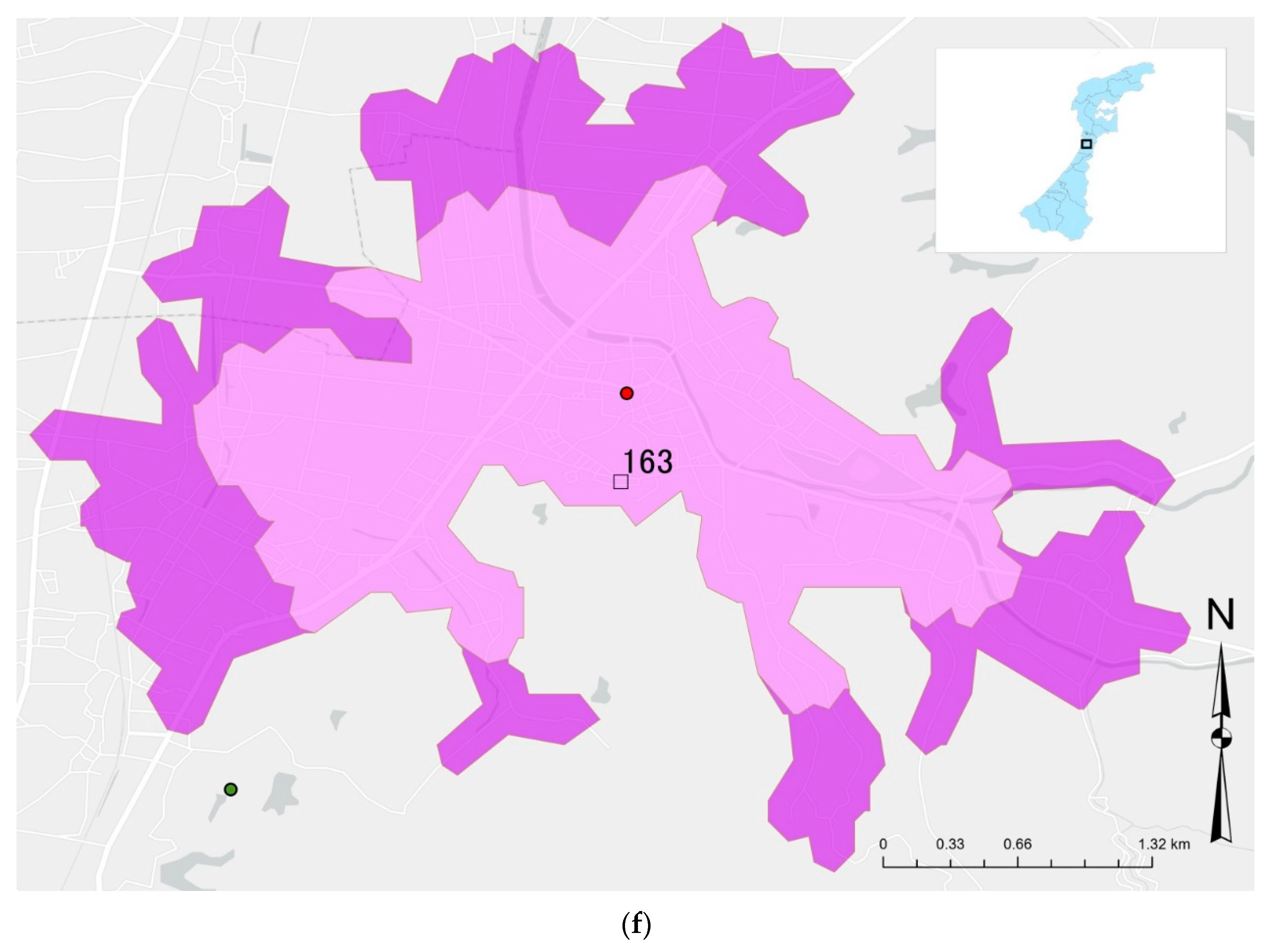

2.6. Service Area Analysis of Distance from GHs to SPs to Obtain Daily Necessities

3. Results

3.1. Geographical Distribution of GHs and SPs in ELAs

3.2. Location Status of GHs with No SPs in Their ELAs

3.3. Location Status of GH with Only One SP

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- GHs without SP in ELA cannot train their residents in shopping skills as defined in the CICSM;

- For older people with mental illness, distant SPs can interfere with shopping skills training;

- GHs with only one SP may not be able to provide adequate shopping skills training because residents who experience delusions about the SP may refuse to access it.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Visions in Reform of Mental Health and Medical Welfare. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2004/09/dl/tp0902-1a.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of Medical Facility (Static/Dynamic) Surveys, and Hospital Reports in 2002. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/iryosd/02/index.html (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of Medical Facility (Static/Dynamic) Surveys, and Hospital Reports in 2014. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/iryosd/14/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Materials Related to Mental Health, Medical Care and Welfare. Available online: https://www.ncnp.go.jp/nimh/seisaku/data/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Guideline of Community-Based Integrated Care System for People with Mental Illness. Available online: https://www.mhlw-houkatsucare-ikou.jp/guide/h30-cccsguideline-all.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Prince, J.D.; Akincigil, A.; Kalay, E.; Walkup, J.T.; Hoover, D.R.; Lucas, J.; Bowblis, J.; Crystal, S. Psychiatric Rehospitalization Among Elderly Persons in the United States. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attili, T.; Atti, A.R.; Moretti, F.; Pedrini, E.; Forlani, M.; Bernabei, V.; Bonafede, R.; Ronchi, D.D. Leading Cause of Re-Hospitalization in an Italian Acute Psychiatric Unit: Preliminary Results. Eur. Psychiatry 2011, 26, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanouchi, Y. Considering Community “Recovery” from Hospital Discharge Rate and Re-Hospitalization Rate. J. Ment. Health 2018, 64, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Corigliano, V.; De Carolis, A.; Trovini, G.; Dehning, J.; Di Pietro, S.; Curto, M.; Donato, N.; De Pisa, E.; Girardi, P.; Comparelli, A. Neurocognition in Schizophrenia: From Prodrome to Multi-Episode Illness. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.D.; Heaton, R.K.; Paulsen, J.S.; Palmer, B.W.; Patterson, T.; Jeste, D.V. The Relationship of Neuropsychological Abilities to Specific Domains of Functional Capacity in Older Schizophrenia Patients. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 53, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipskaya, L.; Jarus, T.; Kotler, M. Influence of Cognition and Symptoms of Schizophrenia on IADL Performance. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2011, 18, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgutshini, T. Risk Factors for Psychiatric Re-Hospitalization: An Exploration. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 19, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romansky, J.B.; Lyons, J.S.; Lehner, R.K.; West, C.M. Factors Related to Psychiatric Hospital Readmission Among Children and Adolescents in State Custody. Psychiatr. Serv. 2003, 54, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Welfare Service for Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/hukushi_kaigo/shougaishahukushi/service/naiyou.html (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview about Survey of Social Welfare Institutions in 2008. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/fukushi/08/dl/kekka-jigyo1.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview about Survey of Social Welfare Institutions in 2019. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/fukushi/19/dl/kekka-kihonhyou02.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Future Direction of Measures for People with Mental Illness Who Have Been Hospitalized for a Long-Term to Facilitate Transition from Institutional to Community Setting. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-shingikai-12201000-shakaiengokyokushougaihokenfukushibu-kikakuka/0000051138.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Kopelowicz, A.; Liberman, R.P.; Zarate, R. Recent Advances in Social Skills Training for Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2006, 32, S12–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, A. Using GIS for Determining Variations in Health Access in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oh, K.; Jeong, S. Assessing the Spatial Distribution of Urban Parks Using GIS. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2007, 82, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifu, S.; Stellmacher, T. Accessibility of Public Recreational Parks in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A GIS Based Analysis at Sub-City Level. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2021, 57, 126916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheiïkh, R. GIS-Based Services Analysis and Multi-Criteria for Optimal Planning of Location of a Police Station. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2022, 35, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Li, Y.; Pan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, X. Study on Urban Fire Station Planning Based on Fire Risk Assessment and GIS Technology. Procedia Eng. 2018, 211, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa Prefectual Government. Ishikawa Plan for People with Disabilities in 2019. Available online: https://www.pref.ishikawa.lg.jp/fukusi/oshirase/documents/plan2019_book.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Okayama, T.; Usuda, K.; Okazaki, E.; Yamanouchi, Y. Number of Long-Term Inpatients in Japanese Psychiatric Care Beds: Trend Analysis from the Patient Survey and the 630 Survey. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAVITIME. Supermarkets Lists in Ishikawa Prefecture. Available online: https://www.navitime.co.jp/category/0202/17/ (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Google Maps. Available online: https://www.google.co.jp/maps/@36.6084096,136.6523904,14z (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- NAVITIME. Convenience Stores Lists in Ishikawa Prefecture. Available online: https://www.navitime.co.jp/category/0201/17/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- NAVITIME. Drugstores Lists in Ishikawa Prefecture. Available online: https://www.navitime.co.jp/category/0206005/17/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Ishikawa Prefectual Government. Information about Social Resources. Available online: http://www.pref.ishikawa.lg.jp/fukusi/kokoro-home/kokoro/shiryou.html (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Shimada, H.; Makizako, H.; Doi, T.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Suzuki, T. Incidence of Disability in Frail Older Persons With or Without Slow Walking Speed. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempfer, M.V.; Hamera, E.K.; Brown, C.E.; Cromwell, R.L. The Relations between Cognition and the Independent Living Skill of Shopping in People with Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 117, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, S.-A. Is a Program to Improve Grocery-Shopping Skills Clinically Effective in Improving Executive Function and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living of Patients with Schizophrenia? Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 48, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M.; Yokoyama, T.; Nakaya, T.; Fukuda, Y.; Takemi, Y.; Kusama, K.; Yoshiike, N.; Nozue, M.; Yoshiba, K.; Murayama, N. Food Accessibility and Perceptions of Shopping Difficulty among Elderly People Living Alone in Japan. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2016, 20, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Garety, P.A.; Kuipers, E.; Fowler, D.; Bebbington, P.E.; Dunn, G. Acting on Persecutory Delusions: The Importance of Safety Seeking. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsell, Y.; Henderson, A.S. Epidemiology of Paranoid Symptoms in an Elderly Population. Br. J. Psychiatry 1998, 172, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwama, N.; Tanaka, K.; Komaki, N.; Ikeda, M.; Asakawa, T. Mapping Residential Areas of Elderly People at High Risk of Undernutrition: Analysis of Mobile Sales Wagons from the Viewpoint of Food Desert Issues. J. Geogr. Chigaku Zassi 2016, 125, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| No. | Data type | Source | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GHs for People with mental illness (point) | Ishikawa Prefecture website | We created a list of GHs by collecting their names, addresses, and their capacity. We converted the addresses to coordinate values and plotted them (i.e., the center of each building) on a map. |

| 2 | List of Supermarkets (point) | Website of major supermarkets in Ishikawa, navigation map website [26,27] | We created a list of supermarkets by collecting their names and addresses. We converted the addresses to coordinate values and plotted them on a map. |

| 3 | List of Convenience stores (point) | Website of major convenience stores in Ishikawa, navigation map website [27,28] | We created a list of convenience stores by collecting their names and addresses. We converted the addresses to coordinate values and plotted them on a map. |

| 4 | List of Drugstores (point) | Website of major drugstores in Ishikawa, navigation map website [27,29] | We created a list of drugstores by collecting their names and addresses. We converted the addresses to coordinate values and plotted them on a map. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nagayama, Y.; Nakai, H. Community-Based Integrated Care System for People with Mental Illness in Japan: Evaluating Location Characteristics of Group Homes to Determine the Feasibility of Daily Life Skill Training. Challenges 2022, 13, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe13020038

Nagayama Y, Nakai H. Community-Based Integrated Care System for People with Mental Illness in Japan: Evaluating Location Characteristics of Group Homes to Determine the Feasibility of Daily Life Skill Training. Challenges. 2022; 13(2):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe13020038

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagayama, Yutaka, and Hisao Nakai. 2022. "Community-Based Integrated Care System for People with Mental Illness in Japan: Evaluating Location Characteristics of Group Homes to Determine the Feasibility of Daily Life Skill Training" Challenges 13, no. 2: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe13020038

APA StyleNagayama, Y., & Nakai, H. (2022). Community-Based Integrated Care System for People with Mental Illness in Japan: Evaluating Location Characteristics of Group Homes to Determine the Feasibility of Daily Life Skill Training. Challenges, 13(2), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe13020038