Abstract

The unprecedented global rise in mental anguish is closely linked with the erosion of our social fabric, economic and political systems, and to our natural environments. We are facing multiple new large-scale threats to health, safety, and security, with a growing lack of trust in others and in authorities. Pervasive stress, anxiety, depression, and uncertainty are of a nature and scale we have never seen before—manifesting in surging violence, community breakdown, domestic abuse, opioid and other drug overdoses, social isolation, and suicides—with alarming new mental health trends in children and young people. This has been made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic and amplified by an exponential increase in the amount and immediacy of information propagated through electronic media—often negative with manipulative intent aimed at dividing opinions through anger and fear. At the same time, there has been progressive erosion of kindness, civility, compassion, and social supports. Here, in this report from a “campfire” meeting held by the Nova Institute for Health, we discuss the importance of understanding the complexity of these interrelated threats which impact individual and collective mental health. Our dialog highlighted the need for efforts that build both individual and community resilience with more empowering, positive, and inspiring shared narratives that increase purpose and belonging. This includes placing greater value on positive assets that promote awareness and resilience, including creativity, spirituality, mindfulness, and nature connection—recognizing that ‘inner’ transitions contribute to shifts in mindsets for ‘outward’ transformation in communities and the world at large. Ultimately, these strategies also encourage and normalize mutualistic values that are essential for collectively improving the health of people, places, and the planet, by overcoming the destructive, exploitative worldviews which created so many of our current challenges in the first place.

1. Introduction: A World in Distress

Our world is in crisis. Numerous large-scale challenges pose threats to the health, safety, and security of individuals and societies, with enormous psychological consequences. An already significant pre-existing decline in mental health was greatly exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, the World Health Organization reported that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a 28% increase in cases of major depressive disorder and a 27% increase in cases of anxiety disorders worldwide. Low and middle-income countries were significantly affected [1].

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were concerning signs of declining mental health. There has been a staggering increase in “deaths of despair” (from suicide, drug use, and alcohol use) in the United States over the past few decades [2], with similar trends in the United Kingdom [3]. Psychological stress is also increasing, notably in young people. In 2019, a United States study documented significant increases in serious psychological distress, major depression or suicidal thoughts, and more attempted suicides in adolescents and young adults [4].

Whether or not the reported increasing rates of mental disorders represents a distinct global pandemic may be a matter of debate, but there is no contention that mental disorders are occurring at unacceptably high levels throughout the world [5]. Mental disorders are associated with personal, familial, and socioeconomic risk factors, including poverty, marginalization, and trauma [5,6]. Anxiety and depression are also associated with the destruction of our physical environments [7,8], and declining physical health with the noncommunicable disease (NCD) pandemic [9]. Thus, while there may be regional differences in how mental distress is manifest, there are common underlying determinants and global trends that warrant more general concern.

As Richard Reuter, editor of the International Journal of Drug Policy wrote recently: “Ever since 1978, with almost clockwork regularity, the [fatal overdose] number has risen by about 7.4% year after year from 1978 to about 2018...Overdose deaths have witnessed exponential growth since 1979...though the findings are specific to the United States, there is nothing about the potential mechanisms that should apply only in that one country” [10].

To consider these complexities and strategies to address them, we held an interdisciplinary ‘campfire’ meeting in April 2022, hosted by the Nova Institute for Health. Our discussions spanned these complexities and explored the common threads and approaches to solutions. Our goal was to underscore the interconnections and interdependencies between the mental health crisis and the many local and global challenges undermining the health of people, places, and planet (Figure 1). This overarching perspective accentuates the need for integrated solutions.

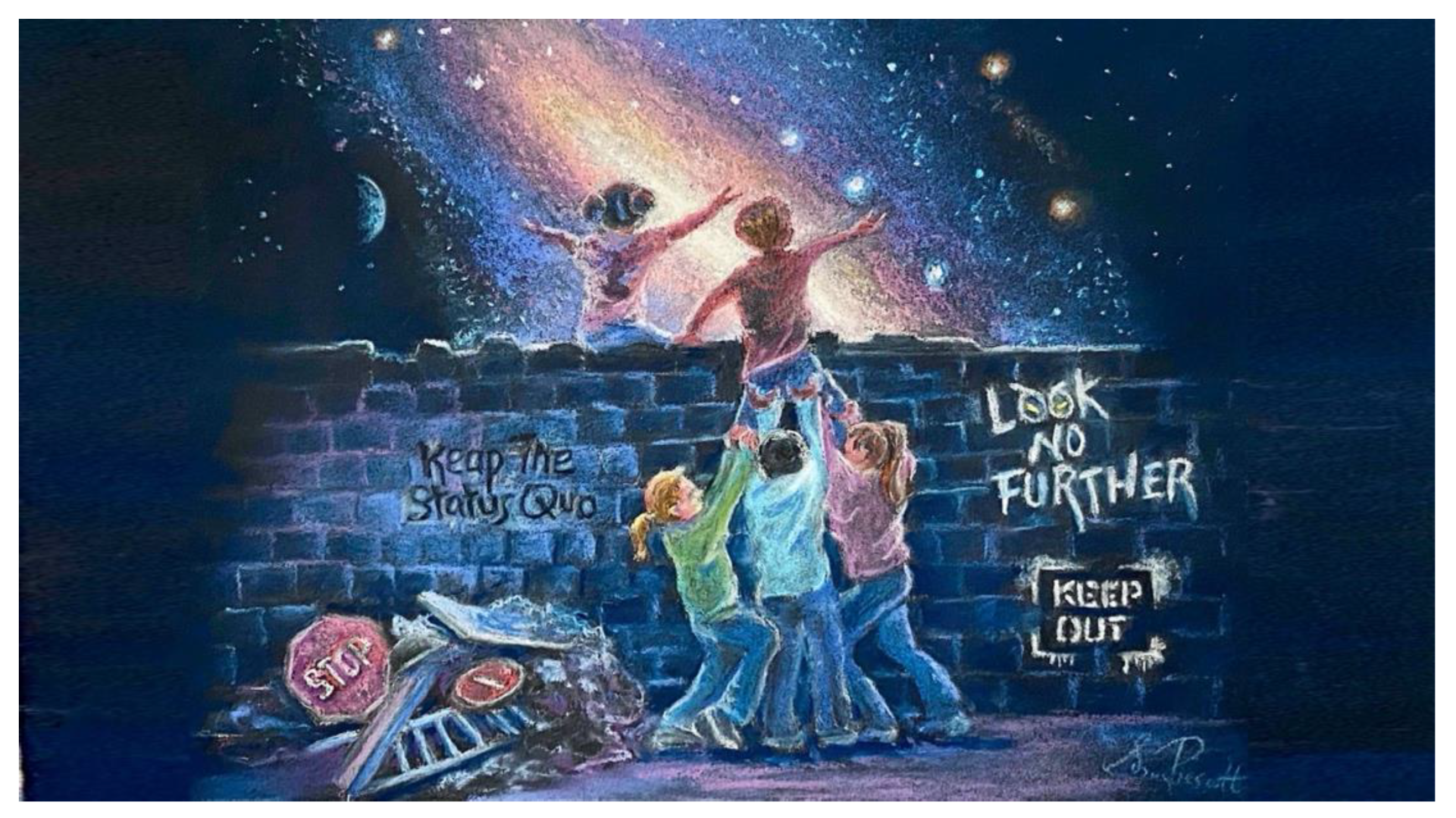

Figure 1.

An era of unprecedented stress, anxiety, and uncertainty of a nature and scale we have never really seen before. We are facing multiple new large-scale threats to health, safety, security, to our social, economic, and political systems, and to our natural environments at all scales. This is being amplified by an exponential increase in the amount and immediacy of information propagated through electronic media, often negative with manipulative intent or ulterior motives aimed at dividing opinions through anger and fear. (Art created by author S.L.P.).

2. Complex Causes and Consequences Require Integrated Perspectives

We cannot consider mental health without considering the complex interactions with our physical health, our social connectedness, and the health of ‘where’ we live and ‘how’ we live (Figure 2). Our relationship with nature, the food we eat, our physical and social activity, and the opportunity (or lack thereof) for healthful choices, have major biological influences on both our physical and mental health.

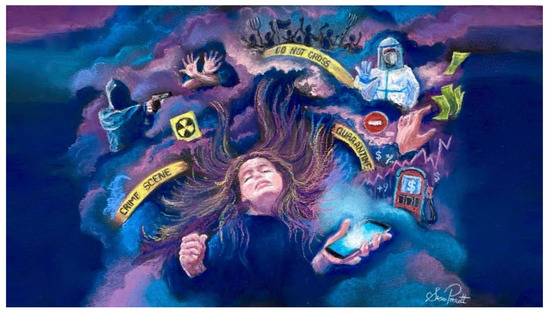

Figure 2.

“Breaking points”: connections between personal and planetary health. Large-scale damage to natural systems and erosion of social environments is implicated in the unparalleled rise in mental and physical disease—through both biological and psychological pathways. As many as 75% of youth are frightened about the future because of climate and environmental concerns. (Art created by author S.L.P.).

Progressive degradation of physical environments, urban grey space (displacing greenspace), a more sedentary screen-based culture, and shifts towards more ultra-processed food and beverages have contributed to a slow-building global pandemic of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) over the past decades—including the exponential rise in mental health disorders. The collective detrimental effects of these large-scale ecological changes, described as ‘dysbiotic drift’, penetrate to the molecular level, including the microbial systems at the foundations of immune and metabolic health. Well-documented associations between mental health (mood, anxiety, and mental clarity) and dysbiotic gut microbiota (with associated inflammation and metabolic dysregulation), provide a common biological pathway for numerous environmental effects at the cellular level. For example, documented changes in human microbiomes and gut health with urbanization have been linked with dietary patterns, antibiotics, emulsifiers, air pollution, nature-disconnection, and innumerable environmental toxins as major determinants of the escalation in virtually all NCDs, and are implicated in physiological vulnerability to mental health disorders.

Equally, there has been degradation of our social environments, community cohesion, and emotional supports—all vitally important for mental health and resilience. We are seeing erosion of kindness, civility, and compassion [11,12]. This loss of ‘positive’ influences has also contributed to community breakdown, isolation, and despair (Figure 1). The rise of social media has promoted a culture of superficial self-obsession, with a documented rise in collective narcissism and declining empathy [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]—with damaging consequences at scale [21].

The frantic, accelerating pace of life with information overload, social media fatigue, and multi-screening, are eroding attention spans [22], memory [23], and adding to mental stress and fatigue [24]. We have seen the emergence of “nomophobia”—the fear of being unable to access one’s cellphone. Screen media is also associated with physical consequences such as body image dissatisfaction, and unhealthy eating, sleeping, and physical behaviors [25,26]. In a vicious spiral, social platforms that provide a platform for individual behaviors often contribute more significantly to collective stress. Both the causes and consequences of mental distress are manifest at scale in significant increases in family breakdown and domestic violence [27] which have surged globally with the COVID-19 pandemic [28].

Concerns over world events, climate change, and wide-spread environmental damage also affect mental health—notably in young people (Figure 2). There are increasing levels of eco-anxiety and solastalgia, the sense of loss and powerlessness induced by the destruction of our natural environment [7]. A survey of 10,000 youths (aged 16 to 25 years) from 10 countries indicated that 75% feel the “future is frightening”, 56% feel that “humanity is doomed”, and 39% are “hesitant to have children” because of global warming [8]. This adds to numerous other concerns about the future, including financial uncertainty in young people [29]. International studies reveal that young people were more vulnerable to stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms associated with the COVID-19 pandemic—an anticipated mental health pandemic that will continue for years to come, as was seen in the aftermath of other global crises, such as the Spanish flu and the Great Depression [29].

Collectively, this complexity underscores that the mental health crisis must be addressed with coordinated approaches that recognize and address the span of influences—from the level of individuals and families to the level of communities and wider societies.

3. A crisis of Relationship: A Common Theme in All Our Global Challenges

As we consider both the causes and the consequences of our many global challenges, we see the human mind and collective mindsets are at the center of this global reality as both ‘driver’ and ‘victim’ of our growing problems, further underscoring the bidirectional relationships between personal and planetary health. In search of common threads, the many intersecting crises of the modern era can be viewed as consequences of “broken relationships”—disconnection from each other, from the natural world, and from our own sense of self and purpose [30] (Figure 3).

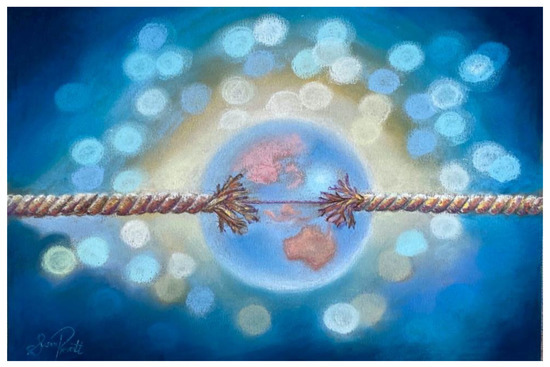

Figure 3.

“Common Threads”: broken relationships in all systems. In broad terms, many of our personal, local, and global challenges arise from broken relationships—with each other, with our communities, with nature, and even with our own sense of purpose. Solutions must lie in restoring bonds, including emotional bonds, for benefits across these scales. (Art created by author S.L.P.).

The importance of “bonds between humans, spirit and nature” and the inter-connectedness of all life [31] are foundational within Indigenous land-based worldviews, and at the source of health for all things [32]. These traditional knowledges have long recognized that interference with the balance of natural systems and rhythms directly impacts human wellbeing—a perspective that encompasses the living energy of nature, with spiritual rather than just materialistic value [33].

This ‘relational’ world view is at odds with the primarily ‘transactional’ nature of western culture. The dominant western narratives are grounded in exploitation, territorialism, overconsumption, and superficial short-term gratification with little regard for consequences [34,35]. We are immersed in predatory narratives with ulterior motives for power or profit—aimed at polarizing opinions through anger and fear, or simply enticing us to consume more products to feel better about ourselves [34].

‘Disconnection from nature’ and the impact on mental and physical health has been magnified by increasing screen time and technology culture, especially in younger generations [36]. Psychologists have argued that available evidence indicates that ‘nature relatedness’ is a basic psychological need [37]. Lower measures of nature relatedness have been linked with lower general health and mental wellbeing [38,39], as well as less concern for the sustainability of the natural environment [40,41]. In contrast, intervention research involving children exposed to biodiversity-rich environments indicates that psychological wellbeing and nature relatedness can improve in tandem [42].

Thus, protecting human health and flourishing for all of life on Earth requires urgent deep structural changes in how we live [43]. However, this cannot be achieved without confronting the underlying value-systems and systems of exploitation and wealth concentration that created and continue to perpetuate our many global challenges of the Anthropocene in the first place, and strengthen efforts to heal territorial, adversarial, and exploitative relationships with nature and each other.

Faced with an existential ‘relationship crisis’ (with ourselves, others, and the world at large) the solutions must lie in restoring bonds, including emotional bonds, across these scales for more connected consciousness that will benefit personal and planetary health (interdependent systems on all scales). This includes the importance of investing in positive emotional assets and shifting mindsets through ‘inner’ transitions that can contribute to ‘outward’ transformation and break the cycle of fear and destruction.

4. Making Connections and Restoring Relationships: Necessitates Intersectoral Collaboration

In the United States, the opioid crisis has been one of the most striking manifestations of declining mental health and community breakdown. There are documented associations between fatal and non-fatal opioid overdose and mental disorders [44]. Although this has been building for decades [2], deaths from drug overdoses have doubled in the United States since 2015 [45]. The steepest rise occurred over 2020, with 100,000 overdose deaths in the first year of COVID-19 pandemic [45], with sustained increases in emergency visits for overdoses in many centers [46]. More than ever, this calls for multidimensional efforts that consider individuals, families, and communities from a life-course and intergenerational perspective in the context of the wider environment, strengthening understanding to enhance connections and positive relationships across these dimensions.

To find opportunities in these challenges, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has several initiatives that seek to look at health promotion and disease prevention in more integrated ways and engage more diverse stakeholders. For example, the All of Us Research Program [47], which was originally launched in 2015 to investigate the links between biology, lifestyle, and the environment in over one million people across the United States, has expanded to consider the wider social determinants of health. There are also more focused efforts at NIH to bring different groups together to integrate coordinated ideas and strategies for specific problems. Two key examples were discussed by Dr Wendy B. Smith (Associate Director, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR), NIH). Each illustrate the growing awareness of connections between person, place, and planet in the context of the major public health crisis.

The first was in response to the opioid crisis. The NIH has been at the forefront of developing biologics and interventions for treatments of substance abuse. In 2018, the OBSSR played a key role in establishing an NIH-wide pain and opioid initiative [48,49]. They brought together diverse group of stakeholders to give deeper more nuanced perspective to the issues of despair, depression, and isolation—with a focus on the social factors, community factors, and the level of resources [48].This broadened engagement from the standard researcher-driven model to include those who do not typically have a voice at the table: representatives from emergency health services, law and justice, economics, and a range of community representatives. Some of the commentaries from this initiative are published in a special supplement of the American Journal of Public Health “US Opioid and Pain Crises: Gaps and Opportunities in Multidisciplinary Research” [50], including legal, government, research, advocate, lived experience, military implications, and racial disparity perspectives.

The second example discussed was the COVID-19 crisis—which has greatly exacerbated the mental health crisis and complicated efforts to address the opioid epidemic. The sheer magnitude of the psychological impacts has served to reduce the stigma of mental health and promote more open conversations. Again, although the COVID-19-crisis has been a global experience, the impact has been very different between individuals and families, depending on work situations, social support systems, level of isolation, access to treatment, and pre-existing risk factors—many of which occur along a socioeconomic gradient. From the NIH perspective, this is another example where the traditional biomedical approach has not been sufficient. There are excellent vaccines and excellent treatments, but the challenges lie in whether they are universally available, and whether people are willing to use them. Political ideologies, polarizing narratives, misinformation, and institutional distrust have penetrated the health agenda in new ways since 2020 [51,52], as another manifestation of the deteriorating social climate. The OBSSR has announced several NIH-wide funding streams for research addressing these wider issues as they pertain to the COVID-19 pandemic and interventions to ameliorate these downstream health impacts.

All these opportunities for diverse engagement have underscored a shared desire to ‘find the positives’ in these situations. Any crisis or trauma can precipitate change through post traumatic growth. A global crisis (or many) may be an opportunity to catalyze action for much needed global change [53]. We can already see that our current predicament has initiated countless new conversations across traditionally siloed disciples and sectors. Considering the future of our children and the generations to come is a powerful perspective for promoting a unifying vision and the long-range implications if we do not act. One consistent emergent theme from many of these conversations was the need for more empathy, altruism, compassion and caring–for each other, for ourselves, and for our planet.

6. The Power of Narrative for Personal and Planetary Mindsets

Storytelling is a central universal feature of the development and propagation of culture [75]. Narratives create our reality, our perceptions of the world, and ourselves—including the barrage of manipulative narratives employed in advertising and marketing [34]. In particular, the stories we tell our children are vital in promoting healthy mindsets early in life, when many value systems become established—including empathy, social concern, and care for the environment. As such, childhood is a powerful window in which to affect a frameshift in attitudes capable of influencing the future ‘health’ trajectory of individuals, communities, and the wider environment.

Narrative medicine is part of a contemporary movement that underscores the importance of the story in healthcare [76]. While this basic premise is as old as the history of medicine, it is regaining recognition as a powerful tool in communicating and co-creating wellness and health behaviours. In community settings, storytelling promotes cooperative social behavior, equity, and egalitarianism. For these reasons, proactively employing constructive narratives is an important tool in addressing health challenges at both the personal and the planetary scale (Figure 5).

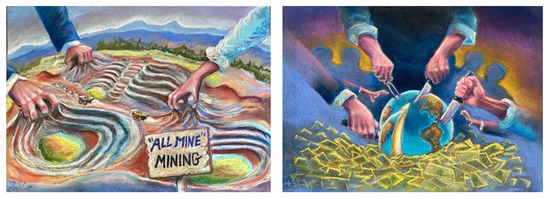

Figure 5.

Mindsets of the Anthropocene:We share the reflections by author J.M.G. in response to this art by author S.L.P.: “For me these images reflect the ‘I, me, mine’ focus of the Anthropocene—literally extracting (mining) all we can take from the Earth. This “my-ning” culture has a lot to do with the development of distress and disease and disconnection. In contrast, healing is the process of becoming whole and connected, of going beyond ‘just me’ towards the wholeness of ‘we-ving’ (weaving) things together and reconnecting to become stronger and more resilient. I enjoyed creating this play on words when I saw the art”. Jeffrey Greeson, in response to art by Susan Prescott.

In 2017, one of the authors (M.E-S.) established a narrative medicine course that includes a planetary health perspective. With a central theme of re-valuing ‘humanity’ in contemporary healthcare practice, it employs narrative competence tools (such as reflection and mindfulness) to re-conceptualizing well-being. This considers how narratives can shape health or illness (belief and behaviours) and responses to these. It extends to how narratives govern wider biopsychosocial determinants of health and resilience, and how we see ourselves in the wider world. These perspectives help students appreciate how narratives influence mindsets and attitudes to ourselves, and to our environment, and the ways in which these are connected.

Our health is partly a function of how we see and react to stressful situations, which has implications at the cellular level. Even in the absence of major life challenges, we are exposed to stress-producing stimuli every day. For example, the barrage of stories and memes from social media. Here, our student physicians co-created a more positive narrative around this constant source of stress (shared in Box 2). To ‘change the story’ is to change how we see and feel about something, and to change how it affects us. To change it together builds community and empowers action. A small example of how we can change our story and expand our vantage point every day.

Being more mindful can make us more aware of the many “inner narratives” that shape our beliefs, behaviours and attitudes to ourselves, others, and the world around us. Becoming more aware is the first step to changing limiting belief systems and unhelpful self-fulfilling narratives. We can be more mindful about the “stories” we propagate around us to others.

Box 2. From Digital Immersion to Mindful Awareness: A video narrative created by Medical Students from Cairo University, Egypt *.

“The Internet has become a cornerstone in our way of life.

With over 8 million Facebook page posts, 60,000 Instagram photos, and nearly half

a million tweets generated per minute, it is clearly a force to be reckoned with.

However, this powerful communication tool is a double-edged sword. Consumers,

especially children and teens, can spend hundreds of hours monthly on a wide variety

of different apps available to them. Enter TikTok—the latest addition to the bunch

and one of the most popular video-sharing platforms of all time. It contains a

universe of different topics discussed in the form of short videos, usually less

than one minute, by from creators from all age groups and backgrounds. This can

be an extremely helpful instrument for learning, raising awareness, spreading

cultural knowledge, and building stronger community. But it can also be a tool

to spread misinformation, and negative news, and set negative trends that adversely

affect many of the people watching them. So, as the next generation, it is our

responsibility to use these instruments to build a society that revolves around

the wellbeing of person, place, and planet—and to be true leaders of change in

an era of mind-boggling evolution.

“More mindful awareness is key to coping with a daily barrage

of stressors. By learning how to control our minds, such as with meditation, there

are biological and several hormonal changes that help control our biochemical

stess responses. Just as our great grandmother’s knew, our attitudes, beliefs,

and emotions can influence our health and resilience. As physicians, we need to

radiate positivity towards better caring for oneself and others. Reflection, mindfulness,

and storytelling can promote the prosocial qualities in societies, with hope and

vision towards planetary health in the face of pressing global challenges. This

is not just a set of ideas, but a set of powerful values that can create small

changes towards bigger efforts to in shift illness narratives towards a more hopeful

landscape that optimizes health at all scales”.

* We sincerely thank the medical students for their narrative (see Acknowledgements).

In the wider context, there is great interest in the ways in which a change in narratives can be propagated for positive social change [77]. It is well recognized that “tipping points” for collective change can be achieved by relatively small groups seeding new narratives. While there is debate about the extent to which Chenoweth’s “3.5% rule” (for successful nonviolent social movements against autocratic regimes) applies in western democratic situations [78,79], there is no doubt that small groups can make a large difference [77]. This is more likely if the new ideas resonate (the “stickiness factor”), and if there is a social or environmental need (the “power of context”) [77].

As we consider the many challenges facing societies today, it is clear that criticizing ‘old stories’ will change nothing if we do not have ‘new stories’ to replace them. Improving health (of people, places, and planet) depends on narratives that give greater emphasis to values, purpose, education (especially in young people), positive emotional assets, self-awareness, and mutualism—conditions likely to promote more “positive contagions”.

7. Conclusions: Promoting Connected Consciousness

A core goal of our meeting was to articulate the layered dimensions of our interconnected challenges, consider the elements needed for change, and cultivate the inspiration to act. This also involved “looking over the parapet” to extend the horizon of hope and possibilities (Figure 6). Our discussions underscored that, in an era of broken relationships on every level, solutions lie in pathways to reconnection. Everything is pointing to the need for more connected consciousness—aligning personal and planetary mindsets, for stronger relationships with ourselves, others, and the natural world—because in doing so we also restore our hope and purpose.

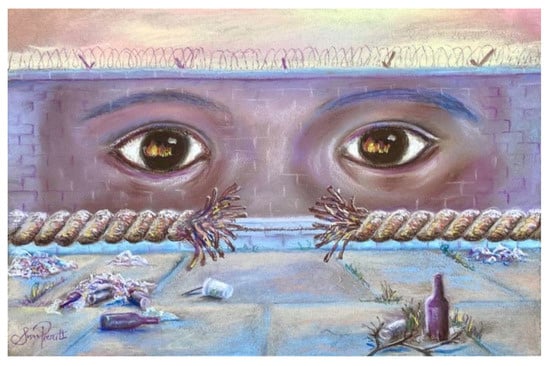

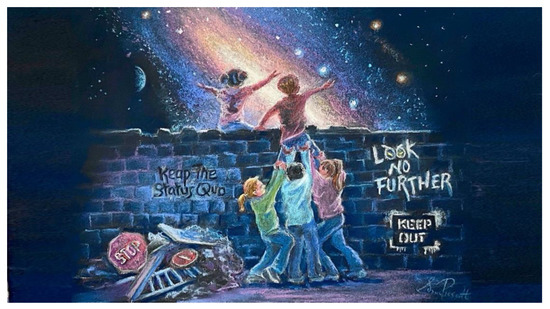

Figure 6.

“Looking over the parapet”: Aspirational goals for new horizons of possibility. (Art created by author S.L.P.).

In considering actions for change, some of the ‘core ingredients’ identified from our meeting are articulated in Box 3. Because our complex threats are interrelated, we also depend on integrated solutions that can only be built through connectivity and meaningful relationships. Such efforts build both individual and community resilience with more empowering shared narratives that also increase purpose and belonging.

Box 3. Actions for Change: Considering the Core Ingredients.

(Including aspirational changes that will only be achieved if we first include them in our goals)

- Widen recognition of the interconnections between our challenges and the limitations of isolated efforts.

- More inclusive, dynamic, creative, empowering approaches that include diverse engagement across sectors and communities.

- Enable, connect, and align “grass roots” efforts with more ‘top down’ approaches to problem—recognizing and elevating the value of local coal-face knowledge.

- Reduce the culture of polarization, marginalization, blame, and retribution which can permeate change agendas—with more efforts to find and amplify common ground and shared purpose.

- Promote a culture of kindness, respect and listening, including learnings from other cultures—in ways that empowers rather than dictates, and challenges authoritarian attitudes and social dominance behaviors.

- Place greater value on self-awareness and self-development for personal empowerment and wellness—recognizing that this also promotes altruism and community resilience (includes spirituality, creativity, nature relatedness etc.).

- Promote community, belonging and connection with others for a greater sense of social responsibility (includes effort to identify suffering for earlier intervention).

- Promote connection to nature to improve physical, mental and social health—and sense of environmental responsibility (includes effort to create healthier, safer community spaces).

- Create and promote positive narratives for hope and change, to shift the focus on ‘what is wrong with the world’ to ‘what we can do about it together’—including normalizing reciprocity and more mutualistic value systems.

- Create more tangible pathways for people to engage in meaningful change—as this generates hope, empowerment, and amplifies engagement.

- Businesses, institutions, and organizations act with greater, genuine, social and environmental responsibility towards. It becomes ‘unacceptable’ to act against the interest of people, places, or planet.

- Ensure that long-range thinking is at the core of all decisions and considers far ranging consequences and long-term effects of actions—including implication for the generations to come.

- Policies and practices that facilitate all these goals.

- Build and encourage connected consciousness—the awareness that all things are connected in ways that recognize the sacred importance of each individual element and its vital contribution and connection to the whole (that large-scale illness or damage of any elements has implications for whole systems).

So, in addition to addressing the many negative aspects of the physical, social, and economic environment that undermine wellbeing, we must place greater value on the positive assets that promote conscious connections and relationships, including creativity, spirituality, mindfulness, nature connection, and efforts to promote social cohesion and resilience—recognizing that both personal and collective actions are needed in tandem—and that each of us can make an important difference.

We quite literally need to change the stories that have shaped our reality and replace self-destructive narratives with more constructive ones. A more connected consciousness gives power to the more mutualistic attitudes and value systems, as we seek to overcome the exploitative worldviews that created our challenges in the first place. To paraphrase the words attributed to John Lennon and Yoko Ono:

“A dream you dream alone is only a dream.

A dream we dream together is reality”.

Above all, we must strive to be “wiser ancestors” and promote hope for the generations to come. For the sake of our children, we need to expand the focus from merely technical solutions to give greater emphasis to our deeper human potential—to our inner dimensions as the real heart of change. This deeper consciousness and relationship with the awe and wonder of life itself will improve mental and physical wellbeing, and our sense of connection with all things.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization of the meeting, S.L.P. in association with the Nova Institute leadership; generating content for meeting used this manuscript, S.L.P., J.M.G. and M.S.E.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.P.; writing—review and editing, J.M.G. and M.S.E.-S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wendy B. Smith, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, Maryland, United States, for her contribution to the meeting and discussions; we also thank the medical students from The University of Cairo, Egypt, who contributed to the presentations: Hania Gaber, Othman Rahed, Omar Yacoub, and Abdelrahman El-Badry. We also thank the members of the Nova Institute for Health and the planetary health community, including the inVIVO Planetary Health network and others, for their contribution to discussions at the meeting.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and COVID-19: Early Evidence of the Pandemic’s Impact: Scientific Brief, 2 March 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1 (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Tilstra, A.M.; Simon, D.H.; Masters, R.K. Trends in “Deaths of Despair” Among Working-Aged White and Black Americans, 1990–2017. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 190, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augarde, E.; Gunnell, D.; Mars, B.; Hickman, M. An ecological study of temporal trends in ‘deaths of despair’ in England and Wales. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M.; Cooper, A.B.; Joiner, T.E.; Duffy, M.E.; Binau, S.G. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Bhugra, D. Analysis of global prevalence of mental and substance use disorders within countries: Focus on sociodemographic characteristics and income levels. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2022, 34, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunting, L.; Nolan, E.; McCartan, C.; Davidson, G.; Grant, A.; Mulholland, C.; Schubotz, D.; McBride, O.; Murphy, J.; Shevlin, M. Prevalence and risk factors of mood and anxiety disorders in children and young people: Findings from the Northern Ireland Youth Wellbeing Survey. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 13591045221089841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Australas Psychiatry 2007, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usher, C. Eco-Anxiety. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 61, 341–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, M.; Patel, V.; Saxena, S.; Maj, M.; Maselko, J.; Phillips, M.R.; Rahman, A. No health without mental health. Lancet 2007, 370, 859–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, P. What are the implications of the steady 40 year rise in US fatal overdoses?: Introduction to a special section. Int. J. Drug Policy 2022, 104, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurbrugg, L.; Miner, K.N. Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Workplace Incivility: Who Is Most Targeted and Who Is Most Harmed? Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rosen, C.C.; Koopman, J.; Gabriel, A.S.; Johnson, R.E. Who strikes back? A daily investigation of when and why incivility begets incivility. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1620–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M.; Foster, J.D. Mapping the scale of the narcissism epidemic: Increases in narcissism 2002–2007 within ethnic groups. J. Res. Pers. 2008, 42, 1619–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K. Birth Cohort Differences in the Monitoring the Future Dataset and Elsewhere: Further Evidence for Generation Me-Commentary on Trzesniewski & Donnellan (2010). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, K.D.; Bernhardt, P.C. Comparing Millennials to pre-1987 students and with one another. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2010, 12, 579–602. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.K.; Benavides, P.; Heo, Y.H.; Park, S.W. Narcissism increase among college students in Korea: A cross-temporal meta-analysis (1999–2014). Korean J. Psychol. 2014, 33, 609–625. [Google Scholar]

- Billstedt, E.; Waern, M.; Falk, H.; Duberstein, P.; Ostling, S.; Hallstrom, T.; Skoog, I. Time Trends in Murray’s Psychogenic Needs over Three Decades in Swedish 75-Year-Olds. Gerontology 2017, 63, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, H.C.; Varnum, M.E.W.; Grossmann, I. Global Increases in Individualism. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1228–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, S.; Farley, S.D.; Donahue, J.J. Grandiosity on display: Social media behaviors and dimensions of narcissism. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2018, 134, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, J.L.; Campbell, W.K. Narcissism and Social Media Use: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2018, 7, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, A.C.; Prescott, S.L. Planetary Health: We Need to Talk about Narcissism. Challenges 2022, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J.S.; Pody, B.C.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.; McDonough, I.M. The effect of cellphones on attention and learning: The influences of time, distraction, and nomophobia. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debettencourt, M.T.; Cohen, J.D.; Lee, R.F.; Norman, K.A.; Turk-Browne, N.B. Closed-loop training of attention with real-time brain imaging. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; He, J. “Why Are You Running Away From Social Media?” Analysis of the Factors Influencing Social Media Fatigue: An Empirical Data Study Based on Chinese Youth. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 674641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, L.; Kirschen, G.W.; LeBourgeois, M.K.; Gradisar, M.; Garrison, M.M.; Montgomery-Downs, H.; Kirschen, H.; McHale, S.M.; Chang, A.M.; Buxton, O.M. Youth Screen Media Habits and Sleep: Sleep-Friendly Screen Behavior Recommendations for Clinicians, Educators, and Parents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 27, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rounsefell, K.; Gibson, S.; McLean, S.; Blair, M.; Molenaar, A.; Brennan, L.; Truby, H.; McCaffrey, T.A. Social media, body image and food choices in healthy young adults: A mixed methods systematic review. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandan, J.S.; Gokhale, K.M.; Bradbury-Jones, C.; Nirantharakumar, K.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Taylor, J. Exploration of trends in the incidence and prevalence of childhood maltreatment and domestic abuse recording in UK primary care: A retrospective cohort study using ‘the health improvement network’ database. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourti, A.; Stavridou, A.; Panagouli, E.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Spiliopoulou, C.; Tsolia, M.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Tsitsika, A. Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 17, 15248380211038690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, P.; Junge, M.; Meaklim, H.; Jackson, M.L. Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: A global cross-sectional survey. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 110236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K. The Common Thread: It’s a Relationship Crisis. Available online: https://cchange.no/2020/03/relationship-crisis/ (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Alvord, L.; Cohen, E. The Scalpel and the Silver Bear; Bantam: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Redvers, N.; Celidwen, Y.; Schultz, C.; Horn, O.; Githaiga, C.; Vera, M.; Perdrisat, M.; Mad Plume, L.; Kobei, D.; Kain, M.C.; et al. The determinants of planetary health: An Indigenous consensus perspective. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, e156–e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redvers, N.; Poelina, A.; Schulz, C.; Kobei, D.; Githaiga, C.; Perdrisat, M.; Prince, D.; Blondin, B. Indigenous Natural and First Law in Planetary Health. Challenges 2020, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, A.C.; Berman, S.H.; Berman, B.M.; Prescott, S.L. Healing Anthropocene Syndrome: Planetary Health Requires Remediation of the Toxic Post-Truth Environment. Challenges 2021, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.L.; Logan, A.C. Down to Earth: Planetary Health and Biophilosophy in the Symbiocene Epoch. Challenges 2017, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Cando, M.J.; Escandon, S.; Van Dyck, D.; Cardon, G.; Salvo, D.; Fiebelkorn, F.; Andrade, S.; Ochoa-Aviles, C.; Garcia, A.; Brito, J.; et al. Nature relatedness as a potential factor to promote physical activity and reduce sedentary behavior in Ecuadorian children. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D.E.; Pelletier, L.G. Is nature relatedness a basic human psychological need? A critical examination of the extant literature. Can. Psychol. 2018, 60, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martyn, P.; Brymer, E. The relationship between nature relatedness and anxiety. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 1436–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, C.M.L.; Schmitt, M.T. Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harvey, D.J.; Montgomery, L.N.; Harvey, H.; Hall, F.; Gange, A.C.; Watling, D. Psychological benefits of a biodiversity-focussed outdoor learning program for primary school children. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.S.; Pivor, J.I.; Saraiva, A.M. The Sao Paulo Declaration on Planetary Health. Lancet 2021, 398, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Draanen, J.; Tsang, C.; Mitra, S.; Phuong, V.; Murakami, A.; Karamouzian, M.; Richardson, L. Mental disorder and opioid overdose: A systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 647–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Rossen, L.; Sutton, P. Provisional Drug Overdose Data. National Center for Health Statistics. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Soares, W.E., 3rd; Melnick, E.R.; Nath, B.; D’Onofrio, G.; Paek, H.; Skains, R.M.; Walter, L.A.; Casey, M.F.; Napoli, A.; Hoppe, J.A.; et al. Emergency Department Visits for Nonfatal Opioid Overdose During the COVID-19 Pandemic Across Six US Health Care Systems. Ann. Emerg Med. 2022, 79, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program. Available online: https://allofus.nih.gov (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Smith, W.B. Behavioral and Social Sciences Research: Addressing the US Opioid and Pain Crises. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health—Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research NIH-wide Pain and Opioid Initiatives. Available online: https://obssr.od.nih.gov/about/nih-wide-pain-and-opioid-initiatives (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- American Journal of Public Health US Opioid and Pain Crises: Gaps and Opportunities in Multidisciplinary Research. Available online: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/toc/ajph/112/S1 (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Kerr, J.; Panagopoulos, C.; van der Linden, S. Political polarization on COVID-19 pandemic response in the United States. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021, 179, 110892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magarini, F.M.; Pinelli, M.; Sinisi, A.; Ferrari, S.; De Fazio, G.L.; Galeazzi, G.M. Irrational Beliefs about COVID-19: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, A.C.; Berman, S.H.; Scott, R.B.; Berman, B.M.; Prescott, S.L. Catalyst Twenty-Twenty: Post-Traumatic Growth at Scales of Person, Place and Planet. Challenges 2021, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N.S.; Malouff, J.M. The Impact of Signature Character Strengths Interventions: A Meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1179–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Brossmann, J.; Hendersson, H.; Kristjansdottir, R.; McDonald, C.; Scarampi, P. Mindfulness in sustainability science, practice, and teaching. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Logan, A.C.; Berman, S.H.; Scott, R.B.; Berman, B.M.; Prescott, S.L. Wise Ancestors, Good Ancestors: Why Mindfulness Matters in the Promotion of Planetary Health. Challenges 2021, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsson, O.; Bazin, O.; Fisher, S.D.; Goldberg, S.B. Effects of an 8-Week Mindfulness Course on Affective Polarization. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandra, T.K. Achieving triple dividend through mindfulness: More sustainable consumption, less unsustainable consumption and more life satisfaction. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 161, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Slade, R., al Khourdajie, A., van Diemen, R., McCollum, D., Pathak, M., Some, S., Vyas, P., Fradera, R., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, R. EU Officials Being Trained to Meditate to Help Fight Climate Crisis. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/04/eu-bureaucrats-being-trained-meditate-help-fight-climate-crisis (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Wamsler, C.; Osberg, G.; Osika, W.; Herndersson, H.; Mundaca, L. Linking internal and external transformation for sustainability and climate action: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 71, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, J. Mindfulness in politics and public policy. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ruane, C. “Be the change you want to see”: A politician’s perspective on mindfulness in politics. Humanist. Psychol. 2021, 49, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, J.; Bell, R.; Wamsler, C. Reconnection: Meeting the Climate Crisis Inside Out. Research and Policy Report. The Mindfulness Initiative and LUCSUS. Available online: https://www.themindfulnessinitiative.org/reconnection (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Burgess, D.J.; Beach, M.C.; Saha, S. Mindfulness practice: A promising approach to reducing the effects of clinician implicit bias on patients. Patient. Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houli, D.; Radford, M. An exploratory study using mindfulness meditation apps to buffer workplace technostress and information overload. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, e373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, H.J.E.M.; Otgaar, H.; Kalagi, J. Minding the source: The impact of mindfulness on source monitoring. Legal. Criminol. Psych. 2017, 22, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, G.; Weinschenk, A. Something Real about Fake News: The Role of Polarization and Social Media Mindfulness. Amcis 2020 Proceedings (Virtual). Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2020/social_computing/social_computing/8/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Sebastião, L.V. The Effects of Mindfulness and Meditation on Fake News Credibility. The Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 2019, Digital Repository Dissertation. Available online: https://www.lume.ufrgs.br/handle/10183/197895 (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Poon, K.T.; Jiang, Y.F. Getting Less Likes on Social Media: Mindfulness Ameliorates the Detrimental Effects of Feeling Left Out Online. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomantonio, M.; De Cristofaro, V.; Panno, A.; Pellegrini, V.; Salvati, M.; Leone, L. The mindful way out of materialism: Mindfulness mediates the association between regulatory modes and materialism. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 3124–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Z.; Liu, L.; Tan, X.Y.; Zheng, W.W. The moderating effect of dispositional mindfulness on the relationship between materialism and mental health. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2017, 107, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, J.; Lewis, D.; Poland, B.; Sanchez-Pimienta, C.E. Stop ringing the alarm; it is time to get out of the building! Can. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, Z.; Bohme, J.; Wamsler, C. Towards a relational paradigm in sustainability research, practice, and education. Ambio 2021, 50, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prescott, S.L.; Logan, A.C. Narrative Medicine Meets Planetary Health: Mindsets Matter in the Anthropocene. Challenges 2019, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charon, R. The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA 2001, 286, 1897–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gladwell, M. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference; Little, Brown and Company: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chenoweth, E.; Stephan, M.J.; Stephan, M. Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, K.R. Social movements and the (mis)use of research: Extinction Rebellion and the 3.5% rule. Interface A J. About Soc. Mov. 2020, 12, 591–615. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).