1. Introduction

Yann Martel’s

The Life of Pi was originally deemed “unfilmable,” and it was not until director Ang Lee was brought on board that this assessment changed [

1]. In order to make visual portrayal possible, Ang Lee made extensive use of CGI to construct a 3D world that exhibits only a vestigial relationship to its real-life models. Because the film claims (as does the novel) that Pi Patel’s story can prompt belief in God, the persuasiveness of visual representation is a key element in interpreting the film. Indeed, it is impossible to make sense of the film’s extensive use of religious themes without understanding its use of immersive visual effects. This essay details Ang Lee’s extraordinary special effects work as a means of understanding the type of pluralistic, experiential “religion” espoused in the film. Indeed, as we shall see, he describes the making of the film and the effect he hopes to render in the audience in consistently “spiritual” terms. Traditionally, the religious imagination is grounded in community, doctrine, and tradition, but, in this case, the process is reversed. The imagination is ground, realized through religious pastiche and cinematic spectacle, which then forms the primary foundation of “belief,” if belief can be redefined as a hopeful, inspiring type of pluralistic, religiously-inflected experience of narrative.

For Ang Lee, the manufacture of a seamless, aesthetically appealing CGI world is a means of visually affirming the broadly conceived notions of interconnectedness and purpose that he borrows from Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Jewish mysticism. The film incorporates elements of these religions to portray the “better story” that viewers are then invited to believe, with the foundation of their belief being, primarily, their cinematic experience of it.

Pi asks the defining question of the novel after he tells both stories—a long, fantastically elaborate story involving Pi’s relationship with a ferocious tiger on a tiny lifeboat, and a shorter story, cruel but simple:

Pi: I’ve told you two stories about what happened out on the ocean. Neither explains what caused the sinking of the ship. And no one can prove which story is true and which is not. In both stories, the ship sinks, my family dies, and I suffer. So which story do you prefer?

Yann: The one with the tiger. That’s the better story.

Pi: Thank you. And so it goes with God. ([

2], p. 317).

This question appears at the end of the film as well, where instead of reflecting back on a sprawling written story as the “better” one, it points to the compelling visual images that viewers have just seen. Both novel and film purport that the “better story” involves Pi’s survival with Richard Parker; but whereas Martel must rely on vividly narrated descriptions of these interactions, Ang Lee presents us with a sparsely narrated visual portrait in which the natural environment participates in a visual dialogue with Pi Patel enriched through extensive use of CGI.

Martel begins his novel with a “Note” in which he describes a strange meeting with an old man who says: “I have a story that will make you believe in God” ([

2], p. x). The old man sends the author to Pi, now much older and living in Canada, and instructs him to “ask him all the questions you want” about his survival on a lifeboat ([

2], p. xi). The rest of the novel consists of Martel’s attempt to tell Pi’s story “in his voice and through his eyes” ([

2], p. xii). The film largely adopts this layered structure, punctuating Pi’s adventure on the ocean with cuts to the author’s encounter with the adult Pi Patel. However in the film, we do not just

read Pi’s words—we also

see Pi’s story unfold in visual detail. The animals are not merely imagined—they are perceived in visual close-up. The ocean is not just a backdrop—it is a character in its own right, reflecting Pi’s mood, impacting his decisions, and delivering mystical visions to boy and tiger. The novel’s premise is based on the invitation to readers to believe Pi’s story

without seeing it. Viewers of the film, by contrast, are invited to believe Pi’s story

because they are seeing it. The story Pi tells in Ang Lee’s film is visually enhanced, made credible by the CGI and 3D techniques meant to draw viewers into its pluralistic religious perspective.

Brent Plate has observed the ability of both religion and film to “bend” raw materials in the creation of new worlds:

Religions and films each create alternate worlds utilizing the raw materials of space and time and elements, bending each of them in new ways and forcing them to fit particular standards and desires. Film does this through camera angles and movements, framing devices, lighting, costume, acting, editing and other aspects of production. Religions achieve this through setting apart particular objects and periods of time and deeming them ‘sacred,’ through attention to specially charged objects (symbols), through the telling of stories (myths), and by gathering people together to focus on some particular event (ritual).

Ang Lee’s film works in all of these ways. It utilizes the raw materials of space and time to create a new virtual world of “specially charged objects” that are “set apart” in time and space. The film is both myth and ritual, incorporating elements of both, reinforced by digital design intended to frame the ordinary as spectacular.

2. Rituals and Tropes

Real-life rituals punctuated the film’s production in ways that are deeply connected with what happens onscreen, and which echo the film’s largely pluralistic, broad themes of interconnectedness. Elias Alouf, a yoga teacher from Lebanon, helped Sharma “find his spiritual inner tiger” with yoga training sessions as long as four hours per day ([

4], p. 79). Ang Lee also did yoga with Sharma, since “as a filmmaker” Ang Lee “goes through the journey himself” ([

4], p. 79). Ang Lee asked Sharma to pray every night: “He has to kneel down by the bed. But he doesn’t pray to any god—he just designates something that works for him—speaks to that person and confesses” ([

4], p. 124). This off-screen religious engagement is mimicked in the film’s onscreen take on religion, in which Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity, and Jewish mysticism are all utilized as part of a visual argument for life’s interconnectedness.

Drawing on her own Hindu background, Shailaya Sharma, Suraj Sharma’s mother, engineered an

aarati ceremony to mark Sharma’s entry into his role as Pi Patel.

Aarati is a ceremony of blessing for transitional moments in life. Several participants, including Sharma, his mother, and Ang Lee gathered in a small room with a table with incense, a symbolic

guru dakshina shawl, plantains, betel leaves, and additional offerings. Shailaja Sharma said: “Since Suraj was to embark on a very significant journey with Ang, we definitely wanted to perform

aarati for Ang and demonstrate our commitment, pride in him, respect, love, and devotion” ([

4], p. 48). The ceremony involved the lighting of candles, incense, and the draping of a fabric over Ang Lee. Prayers followed, with Sharma kneeling at Ang Lee’s feet. Shailaja relates that: “Sharma’s grandmother had instructed that he should prostrate himself before Ang and accept him as his guru as he was going to be trained and educated in a new discipline by Ang” ([

4], p. 48). The ceremony made Ang Lee uncomfortable, but he says he was able to view it in the context of his own Confucian culture: “I have to be the righteous man so Sharma can follow me, not just obey me. I have to deserve

him” ([

4], p. 48). David Womark recognized a “very deep emotional connection between Ang and Sharma” ([

4], p. 79). The production of the film was marked by a number of such constructed rituals, all drawing broadly on existing religious practices but transforming them to induce a sense of symbolic passage for the crew. Even the film’s locations reflect a broad sweep in cultural influence. The company responsible for most of the visual effects, Rhythm & Hues, has offices in Los Angeles (United States), Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), Vancouver (Canada), and Mumbai and Hyderabad (India). Much of the filming, however, especially the water sequences, took place in an abandoned airport in Taichung (Taiwan) ([

4], p. 15). Imagery and architecture were taken from sites in Pondicherry and Munmar (India).

The filming of

The Life of Pi began with a ritual Ang Lee calls the “big luck ceremony,” a quasi-religious event that takes place at the start of every Ang Lee production. The ceremony is an “adaptation of an old Chinese tradition,” made new for use with film production. A table is laid with offerings for the gods, including cakes, fruit, tea and flowers, and sometimes an entire cooked pig. The cast and crew hold incense while Ang Lee says a prayer. Everyone bows in four directions to frighten away evil. Then Ang Lee shouts “Action!” and a gong is struck [

5]. David Womark has wittily remarked that: “For every location in [

The Life of Pi], every stage, every time we went anyplace, we thanked the gods. And I will tell you something: this is the first water movie in the entire history of filmmaking to come close to its schedule” ([

4], p. 84). Despite the obvious elements of ritual at work here, Ang Lee says that the “big luck” ceremony “is not overtly religious.” When directing cast and crew to respond during the ceremony, he says: "You pray to whoever is up there blessing us” [

5]. He elsewhere relates: “It’s a moment of quiet. You never ask for good luck, just the important small things, like safety and smoothness. It’s like you don’t pray to God to win the lottery, you say, ‘give me strength’. Its the same principle” ([

4], p. 84). The adapted nature of these religious rituals was obviously accommodating to a variety of backgrounds in cast and crew. Ang Lee’s rituals were influenced by existing religions but are also about the filmmaking process

itself as a kind of religious process.

In addition to rituals

about the film, there were also a number of rituals depicted

within the film, but which reflect the same loosely pluralistic approach. The film’s portrayal of religion depends heavily upon research completed by David Magee, the screenwriter, who grew up in Flint, Michigan—as far from Pondicherry as you can get. Magee admits that he had a hard time at first, since he had such little familiarity with some of the religious traditions, especially Hinduism. He read books about comparative religion, studied Indian folktales, looked at mosque and temple design, learned about rituals, listened to South Indian classical music, and watched Indian dance. He read history, comic books, epics, and essays. He looked at paintings and watched films ([

4], p. 27). He then shared his findings with Ang Lee, and the two planned out how to handle new visual portrayals of rituals in the film, drawing on the basic outlines in Martel’s novel where possible. The film’s awareness of world religions, then, is filtered heavily through the perspectives of an American screenwriter, a Taiwanese-born director, and a Spanish-born Canadian novelist. It is pluralistic, to be sure, but not especially nuanced. It could be argued that

The Life of Pi engages too simply with vast, ancient, complex, and geographically shaped religious traditions. This is part of the puzzle of the film: its religious message is trite, but the techniques used to produce that message are so visually appealing that– at least for a while—one

wants to buy into Ang Lee’s pluralistic promise.

The blend of onscreen and off-screen religious experience in

The Life of Pi is reflected in the utilization of real-life religious spaces for the onscreen depiction of Pi’s early spiritual explorations. For Pi’s foray into Christianity, the Holy Rosary Church in Pondicherry was used, situated anew within digitally enhanced pastoral images of tea-growing fields in Munmar (

Figure 1). Ang Lee wanted colorful workers in the shot, so he hired 900 extras and transported them 45 minutes each way, costuming them in bright prints and making them appear to be tea-pickers in the fields—humans in tune with their natural environment. He wanted it to look like “the placement of small figures in a Chinese landscape painting” ([

4], p. 100). We can see similar influences at work in some of the shots of Pi’s boat, so small as to be nearly impossible to spot amidst huge crashing waves. These visual choices reinforce the notion that humans are simply one part of a larger, connected environment.

The mosque shown in the film is Pondicherry’s Jamia Mosque. Film crews got permission to shoot only on the outer areas of the building. However, Ang Lee needed Pi to experience a sense of entry to visually parallel his exposure to sacred spaces in Hinduism and Christianity. The Jamia Mosque became the only one of the religious buildings to involve digital manipulation of the sacred space itself, as the camera crew put up a blue-screen on the threshold of the mosque so they could add in the praying crowd (

Figure 2) ([

4], p. 102). Despite the structural parallels of three sacred buildings to visually represent Pi’s exploration of the three faiths, the overall treatment of Islam in

The Life of Pi is shallower than the treatment of Hinduism and Christianity. This limited treatment may be a nod of respect toward traditional Islam’s reticence about visual portrayal of living things. Some Muslims object to visual representation of living things because they want to honor God as the only rightful maker of all living creatures. As a result, much of Islamic art and architecture relies heavily on abstract geometric forms and floral patterns, rather than showing people or animals. From a traditional Muslim point of view, then, one could argue that CGI artists are playing God when they create the digitally rendered animals that inhabit Pi’s world.

The novel relates that the form of Islam modeled for Pi most strongly is Sufism, a mystical mode of Islam that focuses on the unity of all living creatures within the Godhead. The “pious baker” in the novel who introduces Pi to Islam is a seeker of

fana, or “union with God” and explicitly identifies himself as Sufi ([

2], p. 61). Sufis, like mystically minded Jews, Christians, and Hindus, see the world as intimately connected to a Creator at the root of all things. This notion further invites recognition of connectedness between the elements of nature, as all have the capacity to manifest God’s singular purpose. Perhaps, then, the lighter treatment of Islam in Ang Lee’s

Life of Pi can be explained simply by the difficulty of visually representing the Sufi notion of

fana. Instead, the notion of connectedness borrowed from Sufism shows up in more general forms, in the CGI-controlled environments that, as we shall see, depict an interdependent world tightly managed with purpose.

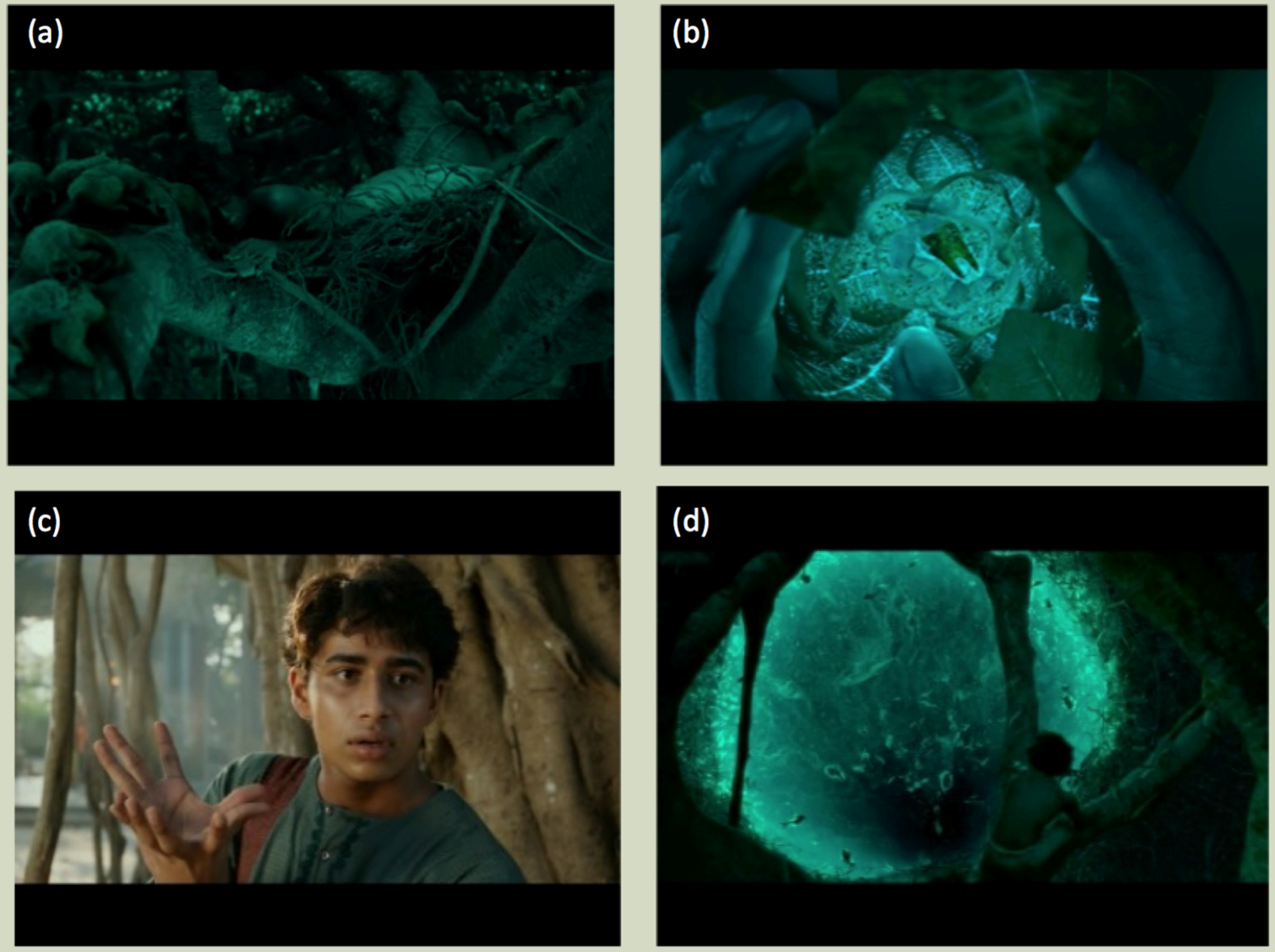

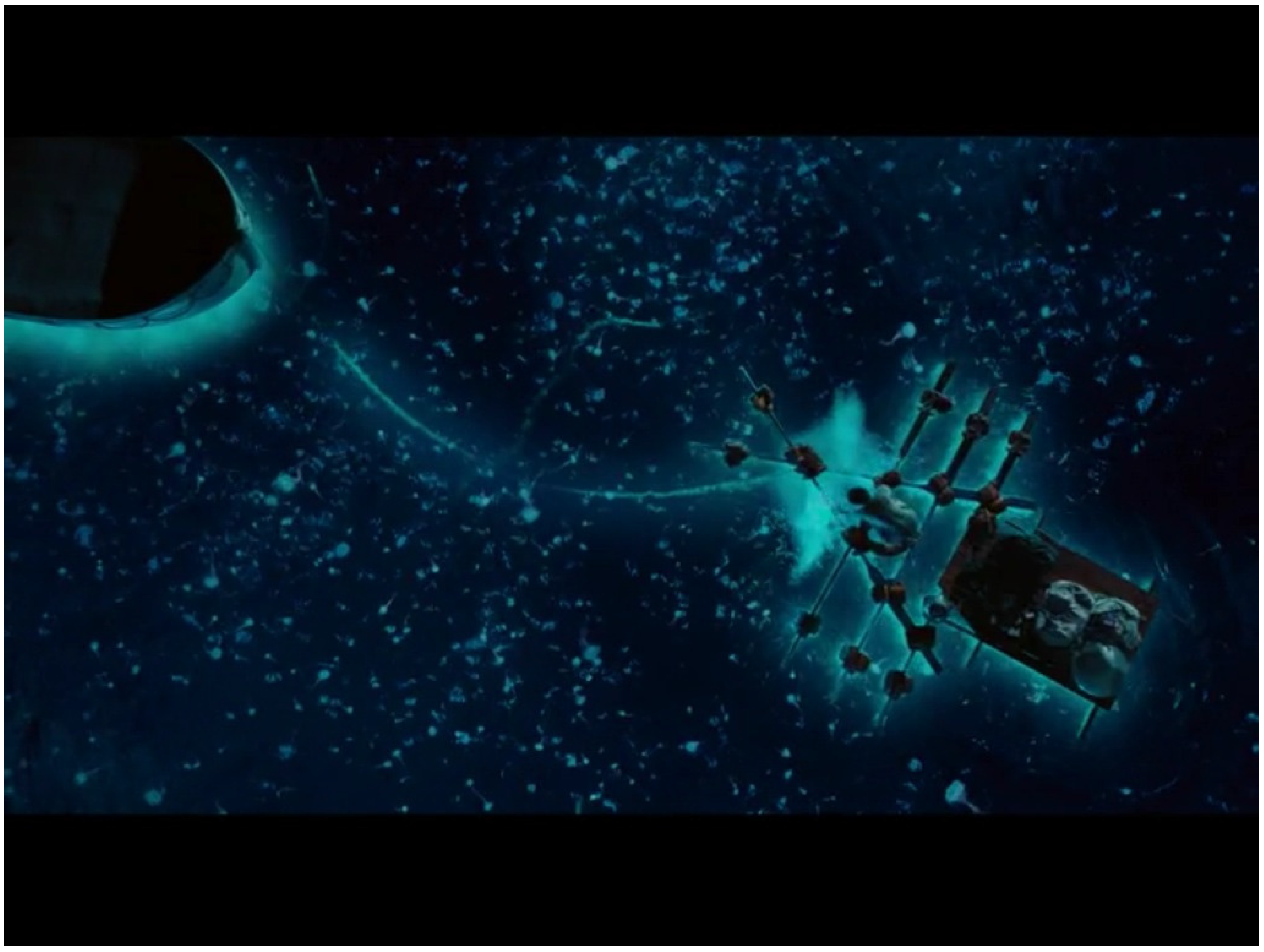

Hinduism gets the fullest visual treatment of any religion in the film. This makes sense, given the importance of Indian culture in the film’s storyline. The crew used the Sri Gokilambal Thirukameshwara Hindu Temple in Villianur, six miles from Pondicherry, as a visual model. Here, crew not only got inside the space, but used it for newly engineered religious rituals affiliated with the film. At the temple, Ang Lee adapted and filmed an elaborate Hindu ceremony meant to honor Vishnu, creating visual echoes of pinpoint lights that would recur throughout the film: during young Pi’s prayers; on the carnivorous island; and while Pi is suspended in the water above the sunken ship. The ceremony was based on a ritual that Ang Lee had read about in research materials for the film and was based on descriptions of a real procedure that had taken place at another temple.

In Ang Lee’s re-creation of the ceremony, the deity is floated around a basin near the temple while musicians play for the god on a raft (

Figure 3). For Castelli, the experience was authentic largely because of the inclusion of numerous Hindu extras, including “the entire populations of a number of local villages recruited for that one scene” ([

4], p. 103). The authenticity of the puja ritual was enhanced by full participation by cast and crew: “Everyone in the production participated in lighting the lamps and launching them across the water” resulting in about 3000 floating lights. An assistant on the film, Kho Shin Wong, reports: “The process was almost like more than just the filming of a movie. In the way that Ang embodies the entire movie all the time, we were able to help embody that aspect of it” ([

4], p. 103). Ang Lee said that: “It was a very, very exciting night. Nothing like it, very spiritual” ([

4], p. 103). This was more than just staging of a visual spectacle; it was a ritual itself, borrowed from Hinduism but transformed to support a message of symbolic unity in accord with the film’s own spiritual message.

The temple lights ritual had multiple layers: it was a ritual

within the film,

for the film, as well as a ritual

beyond the film with authentic meaning for the extras, the cast and crew, and for viewers. Nitya Mehra, a crewmember, remarked that: “The thirty-million-gods multiplicity of Hinduism is such that this ceremony could be both a complete invention and, at the same time, deeply authentic” ([

4], p. 103). Hinduism certainly allows for adaptation; but something more is also happening here, in that Ang Lee’s film

itself can be viewed as a kind of artistic offering to the gods, (

Figure 4). Just as the gods recline to hear the music played on the raft, so too they sit and view Ang Lee’s film, presumably enchanted by its visual display.

The film portrays a rite of passage through the creation of a story about Anandi, a young woman who is Pi’s first love. Ang Lee says he was struck by a dance class sequence of Bharatanatyam dancing in Kalakshetra, as portrayed in Louis Malle’s 1960 series

Phantom India (

Figure 5). Ang Lee echoes the visual scenes of

Phantom India, presenting Anandi as a dancer who offers Pi affection as well as the enigmatic wisdom that “the lotus flower is hiding in the forest.” This phrase functions as a prophecy gesturing toward Pi’s time on a forested island as he becomes a kind of “flower” himself, blooming with new awareness. Ang Lee uses visual echoes of the lotus flower throughout the film, complicating Anandi’s prophecy by having Pi discover a human tooth within an eerie lotus-like blossom that he finds on the island and visually associating the lotus with love of Anandi as well as with death. Pi plucks the blossom from the tree in an echo of the Garden of Eden. Embellishing the plot in Martel’s novel, Ang Lee uses visual symbolism to suggest that that the discovery of the lotus tooth “hiding in the forest” offers Pi deeper awareness of the precarious relationship between life and death.

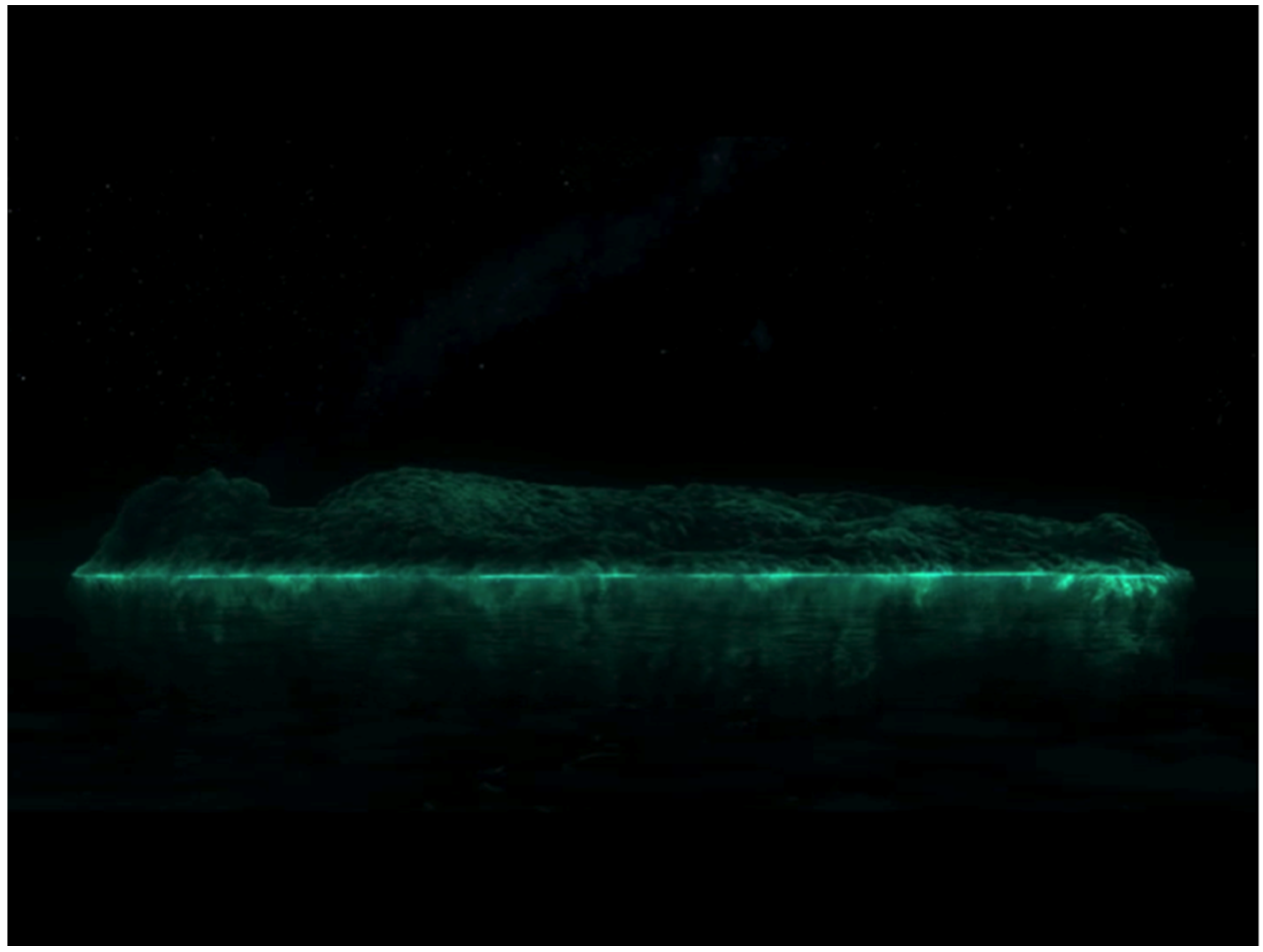

The lotus is closely linked to the symbolism of the banyan tree. For the film’s producers, the banyan tree is “a living metaphor for eternal life, continuously renewing itself even as everything else around it flickers and vanishes” ([

4], p. 31). The banyan tree became the perfect visual complement to the novel’s less explicit treatment of vegetation. Because of its visual appeal, the banyan tree “branched out and took root across the film,” visually linked with the lotus through the hand gestures of Pi as well as through the portrayal of the CGI-made blossoms of the island’s banyan limbs (

Figure 6) ([

4], p. 32). The Hindu

Puranas relate a story about the banyan tree that may be influential here. The

rishi Markandeya was adrift on a cosmic ocean after a fire destroyed his home. A banyan tree appears in the waters nearby him. A boy, who turns out to be Vishnu, is sitting in the banyan tree. Vishnu invites the exhausted Markandeya to enter into him and rest a while. Markandeya is amazed to discover the entire universe inside Vishnu’s body. It is not hard to see how this story inspired Ang Lee, with Pi functioning symbolically as the boy Vishnu as well as the lost-at-sea Markandeya—he is god and exile at once. In the film, the island is constructed via CGI with the banyan tree as model, and in a cutaway shot, we see the virtually-crafted island in the shape of a body in profile, a type of Vishnu asleep on the ocean (

Figure 7).

The entire universe resides in that island-tree, in the mouth of the boy-god Pi who also temporarily resides there, and in the hands of the cinema-god Ang Lee who (also like Vishnu) weaves the story onscreen. Indeed, the immense CGI dream woven throughout

The Life of Pi is like the banyan tree—intricately rooted together underground, a living organism that is much more than its individual parts (

Figure 8). This theme of interconnectedness shows up throughout the film, linked to the twin symbols of the banyan tree and lotus and woven into the portrayal of world religions.

Anandi’s identification as a dancer may mark her as a devotee of Nataraja, an incarnation of Shiva, who is also often seen dancing. Nataraja dances in order to destroy the universe when it has run its course, and to clear the way for a new universe to take its place. As a representative of Nataraja, Anandi gives Pi a “sacred thread” or

rakhi, and wraps it around his wrist as a sign of devotion. The

rakhi is “an image of time passing and [Pi’s] ever more tenuous connection to his past” ([

4], p. 27). As time goes on, we watch the thread age and fray, a visible sign of Pi’s increasingly fragile hold on his old story. It is no coincidence that Pi lets go of the

rakhi (and his relationship to Anandi) by tying the thread to the tree on the carnivorous island. The tree becomes a rich visual symbol, evoking Eden as Pi plucks the tooth-filled “fruit” that prompts him to leave this problematic paradise. Now seeing the world as an adult, Pi willingly leaves the lotus-banyan garden. Perhaps Pi has realized that death haunts us all no matter where we live, whether in a boat with a fierce carnivore or in a tree on a seemingly lush island. Nataraja’s dance

is the wisdom inherent in the “fruit” of the tree: We all move between two universes, one being created and another being destroyed.

3. Visual Effects: Working Cinematic Miracles

In the film, to believe the “better” story is to accept the film’s computer-generated, 3D portrayal of the story of the animals and island as visually authentic. In an essay written on the release of the film, Martel says that: “Life is a breathless adventure that calls you to make choices, not a calculation whose risks you must hedge.” He asks: “Are you directed by the flat edicts of rationality, or open to more marvelous possibilities? Do you need to know for certain, are you limited by that necessity, or are you willing to make leaps of faith?” ([

6], p. 9). The choice, in both novel and in film, is in which story you will believe. However, there are more than just two stories here. In addition to the two stories Pi himself relates in the novel, there are also the stories spun by Martel as author, by the old man Martel says he meets to hear Pi’s story, and of course, there is the visual story now told within the film. Ang Lee uses CGI manipulation to introduce nuances and interpretive threads not present in the novel, and as one would do with any good midrash, he embellishes elements of the story he received.

For example, in both film and novel, allusions to the biblical story of Noah are used to demonstrate the magnitude of God’s power. This association is clear in the film’s early scenes with Pi in the hull of the boat amongst a menagerie of animals (

Figure 9). Early in Pi’s sea journey, he imagines that his brother is still alive. In this fantasy, his brother accuses him of seeing himself like Noah: “You find yourself a great big lifeboat and you fill it with animals? You think you’re Noah or something?” There are also resonances with the story of Job, who is sorely tested through the loss of all that he holds dear. The same God who blesses Pi with beautiful sunsets and fish to eat can remove all of his supplies in a moment of indifference. In the film, we see this power demonstrated in the extended 3D scenes of Pi’s encounter with the ocean. Deborah Potter, correspondent for

Religion & Ethics Newsweekly, remarks that: “Stranded in the ocean, Pi senses God’s presence and power in the beauty of nature, stunningly conveyed in 3-D, but like Job in the Old Testament, he also rails at God for his suffering” [

7]. It is Pi’s suffering that compels him to create the tale that gives him a reason to live. In

The Life of Pi, God’s power is visually demonstrated by 3-D storms that pound and pummel. Pi, unlike Job, finds God’s power enthralling, if also terrifying. Furthermore, for Pi, stories are the most effective way to combat loss. Indeed, stories become the banyan roots that link together otherwise meaningless events, suggesting purpose and design where it seems there may be none.

Screenwriter David Magee and director Ang Lee agree that the novel is about “the different ways in which stories help us through our lives, whether they’re religious stories or, quite literally, the act of storytelling itself” ([

4], p. 19). Martel writes: “[W]e need stories. We’re not just work animals, destined to eat, labor, and sleep. We’re also thinking animals, and there’s no better way to weave together all of our thoughts about who we are and where we’re going and what it all means than through a story” ([

6], p. 9). Stories orient us. They provide purpose, especially in times of hardship. For Magee,

The Life of Pi is “really about the possibility of finding meaning through the structure that telling stories imposes upon the chaos of life” ([

4], pp. 19–20).

Ang Lee says that artful storytelling is deeply spiritual, since it “turns the infinite into a narrative with a beginning, middle, and end; at the same time, it allows a glimpse of the irrational and the unknown through devices such as images and metaphors.” Storytelling, he says:

provides reassurance, filling an emotional need that rationality denies us. But storytelling is not enough; even as we go about our rational lives, a deep part of us continues to yearn for some direct access to the unknown—we want to belong to it, to surrender to it, and to become the vessels of some power greater than ourselves.

Ang Lee’s disparagement of the “rational” is curious, because The Life of Pi relies heavily upon a computational premise for the spiritual story it tells. The film achieves its imaginative vision precisely by the visual effects that are the meticulous—and rational—work of hundreds of animators working for well over a year. Whether one believes in God or not, The Life of Pi provides access to a greater “unknown” by giving us a visually rich, immersive world of landscapes and animals that invites wonder.

Michael Fink and Jacquelyn Ford Morie offer three instances in which the use of visual effects is called for: first, when there is “no practical way to film the scenes described by the script or required by the director;” second, when using traditional filming methods might endanger someone’s life; and third, when using visual effects saves money due to issues relating to “scale or location” ([

9], p. 3). Ang Lee’s use of visual effects in

The Life of Pi reflects some of these challenges. The story’s intense interaction between a boy and a tiger was potentially dangerous enough that “no production would dare to risk [it], and no insurance company would dare to underwrite [it]” ([

10], p. 54). The choice for visual effects certainly did not save money, however, with an incredible $120 million budget [

11]. Instead of visual effects representing the simplest way to tell the story, in

The Life of Pi they are the result of an intentional, calculated vision. The aim of the producers was to “make the viewer believe that a boy and a tiger coexisted on a tiny lifeboat in the middle of the Pacific Ocean for 227 days” ([

10], p. 81). The goal was believability in terms most viewers would readily accept.

The computational basis of the film is seen in major components like the sky and ocean, but also in the animals with which Pi interacts. The animals are largely digital creations, only some of which were blended with performances by live models. The result is an ability to intensely control the visual storyline. The orangutan, Orange Juice, was shot with a real animal only for the cargo hold shots [

12]. The zebra has no real life referent at all (

Figure 10) ([

4], p. 148). The dream sequence with the whale and squid is a pure phantasm. The 60,000 meerkats on Pi’s carnivorous island are all digital. The hyena had a real-life model, but was rendered digitally for most shots on the boat. The tiger was the most complex entity created by the design team and involved four real-life tiger models and extensive digital creation of the composite tiger used in most of the film. Rather than detract from the film’s sense of aesthetic authenticity, the choice for CGI made the story more possible to portray, since the digital animals could be manipulated in ways that made them at least seem natural.

The design of virtual media figures, says Steve Tillis, is like puppetry, since both endeavors share the “crucial trait of presenting characters through a site of signification other than actual living beings” ([

13], p. 185). Drawing on Walter Benjamin, Tillis points out that real actors have an “aura” of presence that is lost through “mechanical reproduction” when they become screen presences. Puppets experience a similar kind of translation to screen as people since both begin as material originals: “Puppets cannot, of course, feel strange in front of a camera, but their lack of feeling does not obviate the estrangement that takes place when the actuality of their physical presence is reduced to a mere two-dimensional look-alike.” The situation is different for virtually manufactured objects, Tillis says, because they “cannot generally be said to lose their presence in time and space when presented by their particular medium, for their presence is actually created by the medium. They are not media reproductions, that is, but original productions made possible through media” ([

13], p. 183). Ang Lee’s digital animals have no presence beyond their function in Pi’s story. They are not actors, but creations.

North et al. rightly point out that we should not imagine that cinema was ever presented in a “pure, honest state free from the spectres of illusion and deception.” However, the intensive development of digital tools in recent decades has vastly increased how easy it is for images to be “manipulated and faked in the digital realm” ([

14], p. 7). As Tillis puts it, “in the age of media production, it is the aura of the work of art—a work without any unique existence in time and place—that is

created” ([

13], p. 183). One could say, then, that CGI entities like

The Life of Pi’s zebra and squid are aura

only, in that they gesture toward a real thing, but toward no

particular real thing. Although four tigers were used for modeling, Richard Parker points to no single referent either, and took the work of 600 animators working over a year to make, producing the virtual tiger that “snarls, lunges, and swipes at [Pi] with a paw the size of a pie plate” ([

15], p. 75).

The use of animated “puppets” in

The Life of Pi eliminated the threat of working with live animals in a restricted environment. It also allowed for greater freedom of emotional expression in visual storytelling. For example, live shots of a hyena jumping up and down in the boat were spliced with CGI images of a digital hyena running. The two hyenas, fake and real, had to be perfectly matched in post-production, with the result that the digital hyena moves faster than a real animal could, in order to increase the “drama” of its threat ([

10], p. 70). Orangutans are difficult to train for film use and can become violent—thus, an animated orangutan was used for all shots. This choice enabled manipulations of the animal, including Orange Juice’s ability to exhibit a subtle emotional reaction when asked about her missing son. Even with this kind of deliberate shaping of effect, the animating team worked to actively resist the temptation to anthropomorphize the animals ([

10], p. 73). Ang Lee and his team of animators wanted the animals to be believable—but believable in terms of the story Pi was telling.

Purely digital figures like those in

The Life of Pi “are something new, not only chronologically but also conceptually” and “[f]or better or for worse, the age of media production is a new age that must be accounted for on its own terms” ([

13], p. 183). For the animals in

The Life of Pi, aura is split from physical presence, creating a disparity that unnerves viewers who recognize the animals in near-perfect similitude but know that the animals are merely digital creations. This is part of what makes

The Life of Pi unusual in its use of CGI: The animals in

The Life of Pi are compelling not because they show us something extraordinary. Rather, they enchant the ordinary by extraordinary means. It is primarily the method of their creation that enthralls.

Richard Parker most readily inspires what Trachtenberg sees as an instance of the “uncanny,” that uncomfortable response wherein a nonliving entity achieves a degree of realism that nearly fools the viewer, and thus leaves her feeling uncomfortable (

Figure 11) ([

15], p. 85). It is often impossible to tell when there is a real tiger on the screen and when there is a digital one, even though in

The Life of Pi, 86% of the time the tiger is pure effects ([

15], p. 2). The rest of the time, one of the four real tigers appears, mainly in the swimming scenes. These four tigers were videotaped extensively to provide the visual modeling that created Richard Parker, including the muscles rippling beneath his skin and the ten million tiger hairs that were enhanced with “subsurface scattering” of light to make them seem more realistic ([

15], p. 12). The company responsible for the animals, Rhythm & Hues, took their work very seriously, as Westenhofer explains:

We’ve done digital animals before. We try to make them as real as possible, and then they go sing and dance. This was our opportunity to really fool somebody. So I wanted to base every shot on reference. I told Ang [Lee] it is too easy to anthropomorphize something even if you don’t want to. I wanted a real tiger in there to cut with. I wanted to force the bar to be pushed. [The tigers on set] gave us better reference than we would have gotten elsewhere. We had eight weeks with real tigers in the real lighting situation. And Erik De Boer, our animation director, had so much reference that we could comb through. He got close-ups of paws moving.

Richard Parker’s fur and markings were modeled primarily on a tiger named King, though his movements came from all of the tigers ([

4], p. 48). Richard Parker performs in a way that is intrinsically connected to these real tigers: he lunges, pants, leaps, and flexes his paws. He is a fully functional entity within his virtual environment. Trachtenberg explains that to “sustain the dream of the movie,” all the illusions had to reinforce one another and viewers had to perceive the real tigers as of a piece with the virtual tiger: “The tiger had to part the water as he waded through it; the water had to break and swirl around his moving body, affect the fur differently depending on whether it lay above or below the water’s surface.” This feat was even harder than it sounds, since the water and the tiger were part of unique software packages, so technicians “had to find a way to get those packages ‘to talk to each other and to interact’” ([

15], p. 77).

Upon first viewing the film, Peter Trachtenberg reacted negatively to the photo-realism of the fabricated tiger: “But what did I have to get indignant about, except at having been charmed back into a child’s credulity…only to be told that the thing I believed wasn’t real?” The tiger, Richard Parker, a masterpiece of CGI, enacts a kind of “idolatrous authenticity,” promising that every quiver, every sniff, is lifelike ([

15], p. 90). Stephen Prince describes the appeal of visual verisimilitude in contemporary CGI: “Visual effects have always been a seduction of reality, more so today than ever before. This seduction is not predicated upon an impulse to betray or abandon reality but rather to beguile it so as to draw close, study and emulate it, and even transcend it” ([

16], p. 9). Trachtenberg found himself frustrated that the tiger onscreen had no indexical origin; Richard Parker was simply a visual spectacle engineered by digital tools that managed to “make the plausible [seem] conclusive” ([

15], p. 77). Real tiger melded with fake tiger, swimming in real and fake water. Once you recognize the artistry involved, the mesmerizing detail certainly makes you

want to believe Pi’s fantastic story, even if it does not convince you about God.

In the film, the emotional connection between boy, tiger, sky, and sea is portrayed via punctuation of repeated shots in which the four are featured in the same frame and with blended mood (

Figure 12). When Pi is calm, the sea is quiet, the sky radiant, and Richard Parker sleeps. When Pi is agitated, the sea whips into a frenzy, the sky grows dark, and Richard Parker paces. In planning the movie, the script supervisor created a chart detailing Pi’s process of “becoming a tiger” but linking this process also to the visuals of sky and sea. The visual elements were corroborated to support this development and to indicate Pi’s evolving “spiritual state” ([

4], p. 78). Mary Cybulski adds that the visuals of sky and sea reveal about Pi “how healthy he is, how close to God he is, how close he is to being Richard Parker” ([

4], p. 78).

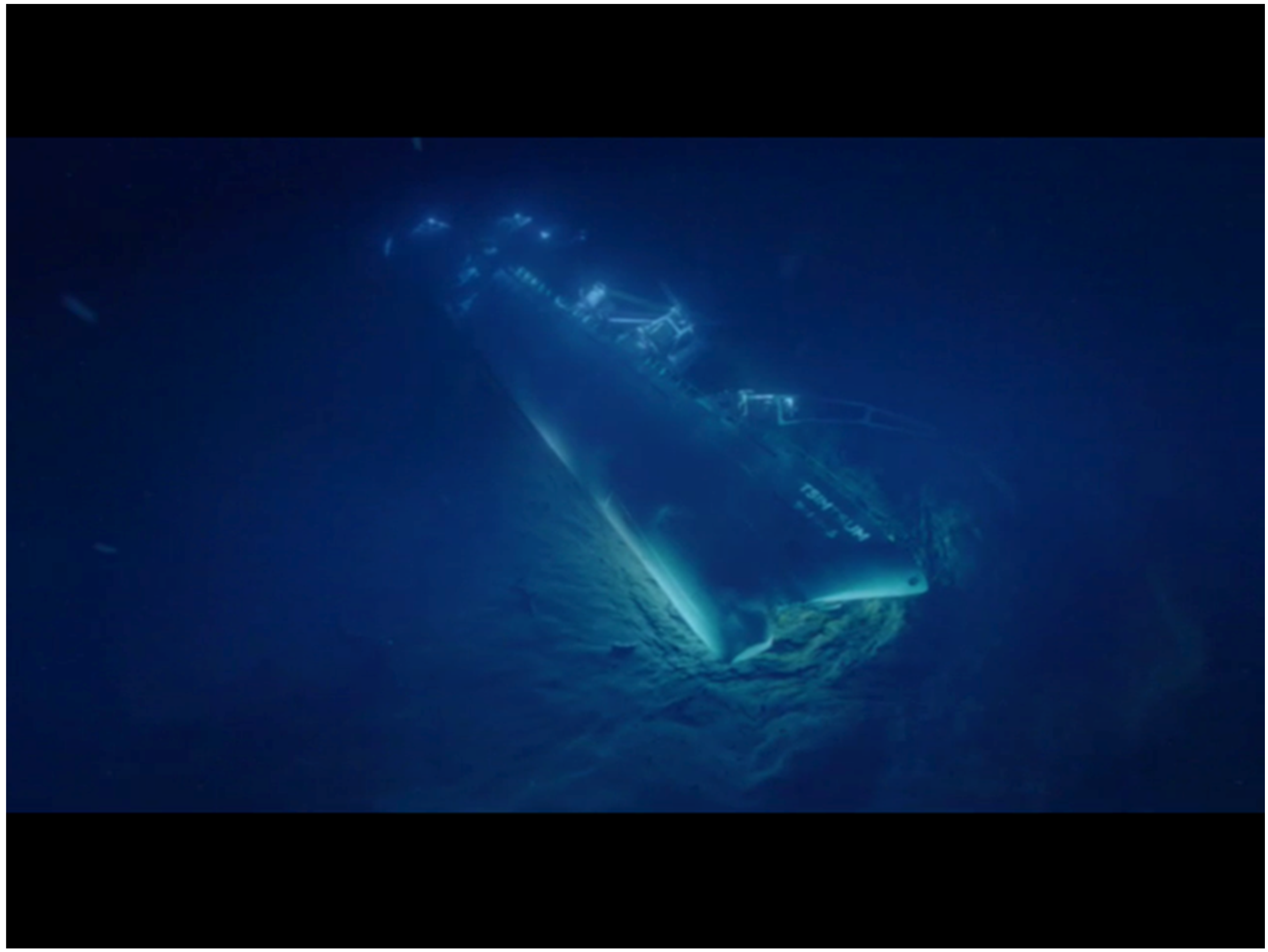

The vast majority of the film takes place on the ocean, a carefully crafted digital entity which Ang Lee wanted to be viewed as “a character” in its own right [

17]. Certainly, CGI has been used to great effect in portrayal of dramatic scenes of the ocean in films like

The Abyss (1989),

Titanic (1995), or

Waterworld (1995). Things have changed a lot since the 1980s and 1990s, though.

The Abyss was the first film to use CGI water effects, and James Cameron’s crew relied largely on underwater filming of live actors with minimal computer manipulation. Nonetheless, it took six months for visual effects designers to create just 75 seconds of computer graphics involving water swirling around an alien. In

Titanic, CGI of water is focused mainly on the sinking of the ship and does not directly shape the plot [

18]. For undersea shots in

Titanic, James Cameron filmed the actual sunken ship. Most shots in

Waterworld were filmed with water sets, except for about 30 seconds of CGI footage that took several months to produce. Twenty years later in

The Life of Pi, almost the entire film is shaped by water produced by CGI.

Using the real ocean was out of the question, since filming would be too difficult in 3D and mood could not be dramatically controlled. Westenhofer explains: “Three-fifths of the movie is on the ocean with Pi smack dab on the surface of the water, and we knew immediately that we couldn’t shoot a 3D movie on the open ocean” [

12]. Instead, Ang Lee had a football-field-sized wave pool constructed on the abandoned tarmac of a Taiwanese airport. The tank was the largest “self-generating wave tank” ever constructed for filming purposes ([

4], p. 54). Wires were mounted atop it in crisscross pattern with a 3D camera rig that moved around ([

4], p. 59). After filming, the water from the wave tank was blended with virtual ocean waves.

The team developed a symbolic vocabulary of swells and textures to match Pi’s emotional state, and wave styles were digitally developed to match them ([

4], p. 54). However, water is not easy to work with in virtual forms, and Westenhofer says it was “the hardest thing to solve” in the entire film [

17]. Castelli notes that “[w]ater, the most basic element of our existence, is fiendishly complicated and time-consuming to simulate and render” ([

4], p. 148). However, since 75 percent of the script takes place on a lifeboat or raft, water had to be dealt with ([

4], p. 52). To facilitate digital augmentation, the wave pool was surrounded with an enormous screen, and the digital water was meticulously modeled on the real ocean. Westenhofer explains:

We did as much research on the ocean as we did the animals. We went out on a Coastguard Cutter into a 50ft storm surge…Every time we wanted to keep some of the tank water we had to blend that with the visual effects water as closely as possible. We had to get the cadence of the waves in the tank water to continue into the digital side and that is very challenging.

Guillaume Rocheron of The Moving Picture Company explains that they used as many as 1.5 billion particles of water in a single shot. The stormy seas scene required 20 machines to simulate, and took a week to calculate [

12]. The water was manufactured not just for authenticity in matching actual waves, but also as a means of indicating Pi’s state of mind. This mode of digital manipulation was also used with the sky, to create a composite emotional palette.

Digital artists selected 120 favorite images of skies from 18,000 HDRIs (high dynamic range images) mostly taken in Florida (

Figure 13). These images were then enhanced with richer colors, sharper lines, and denser patterns and integrated into the film’s emotional landscape of sky and sea. Westenhofer states:

Every sky started from a photograph but there was always the license saying, “This is Pi’s recollection of the journey”—so we could add a little fantasticism to it. Especially, perhaps, the morning he wakes up and the ocean is completely still—though there have been some sailors who have talked to Ang and told him that [lighting] does happen on the ocean and nobody believes them. That sky is more golden than you’re going to get from photographs so we pushed that along.

The most beautiful, awe-inspiring moments in the film—including the impossibly gorgeous morning scene on a “completely still” ocean—are digitally rendered (

Figure 14). This is not surprising, since all film is illusory to some degree; however, the enormous dependence on CGI in

The Life of Pi reveals the role that illusion can play in the representation of quiet, natural environments.

The Life of Pi is an emotional composite of real and fake water, real and fake tiger, real and fake sky, real and fake story, with significant slippage between the poles. Indeed, the film can be read as a residue, an aura, of our own lives—a cinematic echo of our own world, made a “better” story for having passed through CGI control.

The design of the boat, the parched look of skin, knots in rope, all were intended to lull the viewer into investing in the film’s fabricated world. Steven Callahan, a real-life recovered castaway who served as a consultant on the film, says that he was brought in to “bring a kind of authenticity and believability to the film, [to] always lobby for reality” [

19]. In

The Life of Pi, this “reality” was achieved largely through visual effects. Using the example of

Jurassic Park’s dinosaurs, Prince points to the appeal of rich CGI as a means of inviting a kind of pleasure fueled by believability: “No one watching

Jurassic Park was fooled into thinking that dinosaurs were actually alive, but because digital tools established perceptual realism with new levels of sensory detail, viewers could be sensually persuaded to believe in the fiction and to participate in the pleasures it offered” ([

16], p. 33). If Ang Lee has his way, the CGI techniques in the film are meant not just to entertain, but also to convince through fakery. The CGI version of Pi’s tale is the “better story” we are invited to believe.

As opposed to films with spectacular special effects like

Jurassic Park or

The Matrix,

The Life of Pi uses digital techniques to represent the ordinary in extraordinary ways: the earthy grounds of a zoo, the tumultuous waves of the ocean, and the rippling muscles of a Bengal tiger. The digital qualities of the film come via a realistic style: We see thousands of virtual meerkats, but the creatures are not anthropomorphized. We see a vast undersea vision filled with incredible sea creatures, but we read it as Pi’s dream. We see a tiger and a boy become friends, but the animal never loses its potential for ferocity. As Prince notes, computer-generated visual effects are “composites.” They are “artificial collages,” not “camera records of reality.” The visual effects in

The Life of Pi are “fictional truths” with a complex and uncertain relationship to real things ([

16], p. 53). There is a palpable tension here: the film makes its promises of authenticity by grounding its story in a seductive visual illusion.

Visual effects like these challenge long-held presumptions about how real-life images relate to images onscreen. As Prince points out, influential film theorists like André Bazin and Roland Barthes have argued that film depends upon a direct relationship between the object being filmed and what we see on the screen, since “[p]hotographs are said to make documentary claims about the nature of reality” ([

16], p. 148). Even Sergei Eisenstein pointed toward the photographic reliability of individual shots, which (despite their ability to symbolize meaning via montage) exhibit a “tendency toward complete factual immutability [that] is rooted in nature” ([

16], p. 238). The shift toward photorealism via digitally rendered effects has changed this presumption, shifting the “ontological status” of film for viewers ([

16], p. 148). Digitally rendered effects can veer more toward virtual reality than toward photography if they create an immersive enough environment. Prince offers an explanatory comparison between the art of

trompe l’oeil and the work of virtual reality:

The concepts of trompe l’oeil or illusionism aim to utilize representations that appear faithful to real impressions, the pretense that two-dimensional surfaces are three-dimensional. The decisive factor in trompe l’oeil, however, is that the deception is always recognizable; in most cases, because the medium is at odds with what is depicted and this is realized by the observer in seconds, or even fractions of seconds. This moment of aesthetic pleasure, of aware and conscious recognition, where perhaps the process of deception is a challenge to the connoisseur, differs from the concept of the virtual and its historic precursors, which are geared to unconscious deception. With the means at the disposal of this illusionism, the imaginary is given the appearance of the real: mimesis is constructed through precision of details, surficial appearance, lighting, perspective, and palette of colors. From its isolated perfectionism, the illusion space seeks to compose from these elements a complex assembled structure with synergetic effects.

The visual effects of

The Life of Pi seem to lie somewhere between

trompe l’oeil and virtual reality. Visual Effects Supervisor Bill Westenhofer said that as leader of the effect team, his goal was “to make it look like we did nothing at all” ([

4], p. 144). The ordinariness of the ocean, a boy, and a Bengal tiger become remarkable when viewers marvel at the millions of digitally rendered water drops or the intricately rendered tiger paws. Just the shot of the

Tsimtsum sinking contained around 269 million virtual spray droplets, all managed by technicians intending to make them appear as natural as possible ([

4], p. 149). Ang Lee took the basic ingredients of the novel and manufactured an exceedingly complex, visual world that mimics our own, but is much more carefully calibrated. It is, in effect, our own world rendered purposeful onscreen.

4. Pastiche, Myth, Faith

Faith, says Ang Lee, is to jump from the limited viewpoint of the human to the unknown beyond, “and this leap takes place through another dimension” ([

8], p. 13). However, as director, Ang Lee is in complete control of the world he builds; it is hardly an “unknown” even if it may appear wondrous to viewers. The new “dimension,” of film, especially with 3D, invites a further “leap” into another world. Yet the viewer is aware at all times that

The Life of Pi is an illusion, particularly because of the 3D glasses perched on the viewer’s nose. Ang Lee’s use of visual effects is meant to make us see how beautiful our own real world can be by showing us a lovingly, intentionally manufactured one. In a way, this is how religion at its best works too: it shows us an ideal state of affairs, and invites our immersion in that system.

As Plate has observed, both religious and filmic worlds “are made up of borrowed fragments and pasted together in ever-new ways; myths are updated and transmediated, rituals reinvented, symbols morphed” ([

3], p. 4). We see this process at work in

The Life of Pi’s interactions with Judaism, the only religion that Pi does not explicitly sample in his visits to sacred sites, but the one that arguably has the greatest impact on the film’s approach to visual storytelling. In the novel, Martel makes explicit reference to Lurianic Kabbalah early on, indicating that Pi Patel studied it in college, writing his fourth year thesis on Luria’s “cosmogony theory” ([

2], p. 3). Several additional references to Kabbalah occur in the film: Pi tells the writer interviewing him that he teaches a course on Kabbalah at the university, and we get a glimpse of the name of the sunken ship, the

Tsimtsum, glowing eerily at the bottom of the ocean (

Figure 15). These references are enormously important clues, since Kabbalah may be the key to making sense of how storytelling works in the film.

In Kabbalistic mythology, creation begins with a problem: “How can there be a world if God is everywhere? If God is ‘all in all,’ how can there be things which are not God? How can God create the world out of nothing if there is no nothing?” ([

20], p. 261). For God to make anything, he must “withdraw” or “retreat” to make room for creation: He must back away in order to manufacture a blank space—a screen—upon which to make something new. In terms of visual effects, he must draw up a computational matrix on which to place his creations. To accomplish this goal, God’s “whole power” is “concentrated and contracted in a single point” ([

20], p. 260). God withdraws from Godself, leaving a space that is now

not-God—a space in which a new story-world might emerge. As Gershom Scholem puts it: “God was compelled to make room for the world by, as it were, abandoning a region within Himself, a kind of mystical primordial space from which He withdrew in order to return to it in the act of creation and revelation” ([

20], p. 261). This withdrawal, or

Tsimtsum, can be viewed as “the deepest symbol of Exile” ([

20], p. 261).

Ang Lee seems to be fully aware of the rich potential of a Kabbalistic reading as an analogy for filmmaking. In a critical early scene, he shows us Pi hovering in the water “withdrawn” from the sunken ship (

Figure 16). Pi is helpless, pathetic, and broken, exiled from his past and the family he had loved. The name of the ship—the

Tsimtsum—marks this Pi as a new creator being born from the midst of suffering and exile. Similar to God, Pi mourns the loss. The scene of the sunken ship is almost completely manufactured via CGI, with Pi’s body superimposed against a virtual rendering of the boat in the ocean. This moment presents a visual argument that Pi—like God—has been “removed” from his previous identity, producing a grievous rift that can now be filled with something new, and perhaps

must be filled. Storytelling becomes the means by which Pi, as creator, addresses this loss.

One of the distinguishing features of Kabbalah is its insistence that God suffers with us; indeed, creation itself implies a kind of disaster, since God cannot create something that is not God, without cleaving in some way. As a result, God’s new creation is painfully exiled from God, and this fissure is unavoidable. God’s creation takes on a life of its own apart from the creator, just as all stories do—including Ang Lee’s film. Pi, like God, experiences radical exile, and, like God, he copes with devastation by integrating loss into the story itself thereby rendering the pain meaningful. Certainly, Pi did not intend this loss, but one could say that God did not intend loss either when he withdrew into himself in the cosmic Tsimtsum. Into the abyss, these creators then project their stories: God projects the story of humanity; Pi projects the story of the tiger; and Ang Lee projects the story of Pi, using the rich effects of CGI to craft a world that draws us in to Pi’s dream. God, like a cosmic projectionist, emits light into the empty space. Ang Lee, like God, fills the void with stories.

According to Kabbalistic myth, God first tried to contain the light of creation in cosmic “vessels.” We can think of these vessels as attempts to limit divine power by circumscribing it within fixed boundaries in the void. The vessels broke because they were, by their very nature, unable to contain the divine presence. God’s power was just too great. This

Shevirath Ha-Kelim, or “breaking of the vessels” causes “sparks” of divine light to fall into the abyss, marking God’s first attempt at creation as a failure ([

20], p. 265). In some ways, though, this additional rift is inevitable: God’s light is so powerful that it will burst any boundaries put upon it. God

wants to express Himself, to create something new that is

not-God, but this act is inherently destructive and creative at the same time. If we view God as a filmmaker, then,

we are God’s cinematic production—the illusory aura or residue of his expression, the “sparks” that fall into the abyss when God attempts to tell God’s story: we are the visual effects, if you like. There is a mythic tension here between creation and retraction, expression and repression, projection and reception. Ang Lee borrows this resonance for the story of Pi, who also is defined by the relationship between destruction and creation, and who also is marred by loss and driven to create nonetheless.

Ang Lee and screenwriter David Magee appear to know something of the contradictions inherent in Kabbalistic mythology when they use the “Storm of God” scene to evoke the tension between creation and loss. Guillame Rocheron of MPC describes this scene as the “climax” of Pi’s journey, when he is starving and exhausted. The storm was portrayed digitally as “even bigger than what you might see in reality—because it is Pi’s perception of the storm” ([

10], p. 76). In this moment, “a more spiritual dimension enters into the film, a dissolution of the self into the surrounding vast unknown that [Ang] Lee wanted Sharma to access” ([

4], p. 124). Spreading his arms into the storm, accepting that he cannot undo the catastrophe of the

Tsimtsum, Pi shouts: “God, I give myself to you. I am your vessel. Whatever comes, I want to know. Show me.” Pi agrees to be the vessel into which God projects his creative light, even though he understands that such a choice brings with it suffering. Undoing Job’s frustration, Pi willingly bears the pain of creation. He agrees to be God’s story, knowing just what that means. Pi is also the “vessel” into which the film-god Ang Lee projects his

own midrashic story, using visual effects as a means of creating a world that is recognizable as our own, if more enchanted and more dangerous.