2. Levels of Being

Various schemes have been put forward to explain in more detail how human existence is structured into a series of emergent levels. Rauhala proposes four levels:

physical

biological

psychological

spiritual

The first three should be fairly uncontroversial. Also, Rauhala defines the spiritual in a way which should be acceptable to most people irrespective of their philosophical or analytical orientation, not to speak of their religious persuasions or lack thereof. Spirit is not to be understood as a substance of any sort, hence no ontological dualism is implied. Rauhala defines spirit as cogito which has become conscious and capable of experiencing meanings, i.e., having mental representations of the external world as well as of one’s own organic being

and finding them charged with value which goes beyond considerations such as practical use or immediate pleasure. The spiritual has its origin in the phenomenological notion of situatedness, which Rauhala defines as everything to which a bodily existence and cogito happen to be in relation to at a given time including geographical, historical, social, and cultural conditions, as well as intricate patterns of social configuration ([

1], p. 114). Meanings are not limited to symbolization and language but include faculties such as intuition, fantasy, ability to experience feelings and to appreciate beauty, art, and the holy. Individual subjectivity is a form of spirituality as manifested in faculties such as the sheer ability to enjoy existence without the pressures of responsibility and activity, or sensitivity cultivated in peace and tranquillity ([

1], p. 72).

In Rauhala’s scheme between the biological and the spiritual levels there is the psychic level, on which we experience such basic reactions as pleasure and displeasure, satisfaction and dissatisfaction, joy and fear, happiness and anxiety, etc. However, there is no self-consciousness on the psychic level. That is a spiritual phenomenon which requires taking distance from one’s immediate psychic experience and observing it as a phenomenon among others—the psychic experience being thus objectified. According to Rauhala, the spiritual level can only be explored properly when a distinction is maintained between it and the psychological level as its enabling condition ([

1], pp. 65–66). The development of an individual is a process of constant dialectic in which the primary structures are incorporated into and transformed by the developing of higher orders of structure each of which eliminates part of the autonomy of the previous level while acquiring some its own. This process gives new significance to the phenomena on the lower levels. When, for example, sexual desire is transformed into love and caring, a new order is introduced which articulates and governs that desire and related behaviour.

Rauhala’s approach derives from the philosophy of Maurice Merleau-Ponty. He emphasized that the foundation of all that can be achieved culturally rests on our mode of being-in-the world. Merleau-Ponty writes about three levels, the vital (more or less equivalent to Rauhala’s biological level), the psychological, and the spiritual orders of behaviour, each of which is related to the higher as a part to the total. Merleau-Ponty emphasizes that “it is not a question of two de facto orders external to each other, but of two types of relations, the second of which integrates the first.”([

2], pp. 180–81). Merleau-Ponty’s and Rauhala’s views may be characterized as holistic in that all the upper levels which they define function as systems in which a whole influences in a seminal way how its parts behave.

To appreciate what all this entails in terms of the history of ideas, we could not do better than refer to the hermeneutics of Paul Ricoeur. He saw the complementarity between what he called hermeneutics of suspicion and hermeneutics of faith as an essential component of any such account. On the one hand, we have an almost complete reversal of the traditional values of humanities expounded in the post-modern credo of there being no meaning that art could either conceal or reveal, only the simulacrum ([

3], pp. 217–18). The usual suspects of this line of thought are thinkers in contemporary film theory have been Jacques Lacan, Louis Althusser, Michel Foucault, and their followers, but of course the original figures of suspicion are Sigmund Freud, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Nietzsche. In the words of Ricoeur, the aim of these masters is to “carr[y] in reverse the work of falsification of the man of guile,” of an individual subject to various kinds of illusions. Waking him up begins by a reduction which entails explaining consciousness through causes (psychological, social, etc.), through genesis (individual, historical, etc.), through function (effective, ideological, etc.). Yet, although “all three begin with suspicion concerning the illusions of consciousness, and then proceed to employ the stratagem of deciphering … far from being detractors of ‘consciousness,’ [they all] aim at extending it” ([

4], p. 34).

Ricoeur warns us of the threat that we, “the heirs of philology, of exegesis, of the phenomenology of religion, of the psychoanalysis of language” face when we accept this “gift of ‘modernity’”. We must be aware that “the same epoch holds in reserve both the possibility of emptying language by radically formalizing it and the possibility of filling it anew by reminding itself of the fullest meanings, the most pregnant ones, the ones which are most bound by the presence of the sacred to man.” Ricoeur calls for a “logic of double meaning”, a logic which is “no longer formal logic, but a transcendental logic established on the level of the conditions of possibility; not the conditions of objectivity of nature, but the conditions of the appropriation of our desire to be”([

4], p. 48).

3. Dialectic between Reductionism and Holism

The crucial point in the reductionism vs. holism controversy lies in the question of how autonomous each of the higher levels is in respect of the underlying ones. At the extreme ends the strictest determinists allow for no autonomy at all for the higher levels, whereas holists argue that any lower level enables and conditions but does not necessarily determine an upper level. Many scientist and philosophers appear to intuitively favour either reductionist explanations or accounts which acknowledge the non-reducibility of emergent features. This opposition is a fundamental philosophical aporia and cannot be treated here with adequate depth. The briefest argumentation will have to suffice to justify the approach adopted in this article.

Among the most steadfast reductionists are certain neuroscientists who have forcefully challenged the notion of emergence. They wonder whether we really may boldly assume that the levels in the kind of schemes such as those introduced above actually do enjoy any degree of autonomy. Is it not more plausible, they say, to think that everything can be reduced to ever more fundamental elements in the name of the unalterable law of causality? This inevitably leads into treating reduction as the only legitimate form of scientific pursuit. Mary Midgley criticizes such accounts for seeking to boil everything down into a single doctrine without realizing that this is merely one form of responding to the demand for explanatory unity: the matter/mind opposition may just as well be scrutinized by putting mind before matter as vice versa. It certainly does appear that here there is really no purely argumentative way to choose between the two, although philosophers and other scholars as well as many laymen have been strongly inclined to choose between them. As Midgley points out, embracing either monolithic materialism or monolithic idealism consistently leads to strange paradoxes. “What is needed has to be something more like a double-aspect account, in which

we do not talk of two different kinds of stuff at all, but of two complementary points of view: the inner and the outer, subjective and objective” ([

5], p. 142).

Richard Sperry in turn treats this issue as a question of the power of the whole over its parts, i.e., conscious high order cerebral processes exercising a certain power over constituent neural and chemical elements: “The conscious mind is put to work and given reason for being and for having been evolved in a material world”([

6], pp. 296–97). Sperry warns against reductionism “that would always explain the whole in terms of ‘nothing but’ the parts [as this] leads to an infinite nihilistic regress in which eventually everything is held to be explainable in terms of essentially nothing”. By contrast, according to the emergent materialist view, “emergent properties of a system S cannot be derived by any true physical theory from information concerning the elements of S and their interrelations”—thus, the whole may be assumed to be more than the sum of its parts ([

7], p. 22). The more extreme view is that consciousness is by nature something that cannot satisfactorily be explained in functional terms. It has to be complemented with a phenomenological account of what consciousness actually amounts to in terms of being-in-the-world.

The idea that a lower level can explain a higher one is tempting but the path to which it beckons is not as direct as such apparent conceptual simplicity might suggest. Jean-Michel Roy et al. in their introduction to an enormously interesting collection of essays

Naturalizing Phenomenology, state that: “It is … not enough to pile up levels of explanation; they have to be integrated into a single hierarchic explanatory framework that demonstrates their mutual compatibility” ([

8], p. 45). This is a laudable aim, but what does it mean in practice? Cognitive science has traditionally seen as its calling to remain a natural science and to withhold from making any objectively non-verifiable assumptions. According to Roy and his colleagues:

Cognitive Science makes the crucial assumption that the processes sustaining cognitive behaviour can be explained at different levels and varying degrees of abstraction, each one corresponding to a specific discipline or set of disciplines. At the most concrete level the explanation is biological, whereas at the most abstract level, the explanation is only functional in the sense that ”information” processes are characterized in terms of abstract entities, functionally defined.

Furthermore, “Cognitive Science maintains that there is no substantial difference between giving a functional explanation of the information processing activity responsible for the cognitive behaviour of an organism and explaining this behaviour in mental terms.” At its extreme “Cognitive Science claims to have discovered a non-controversial materialist solution to the mind-body problem.” ([

8], p. 5). There has even been a “

Consciousness Boom”, which can be seen “part as an attempt to demonstrate that the principles on which the Cognitive Revolution was based do not rule out a systematic investigation of phenomenological data” ([

8], p. 13). All in all, an ever richer understanding of how being is structured in interrelated levels seems to be on the rise. William Bechtel enhances our understanding of how different levels of inquiry are interrelated: “Inquiries at different levels complement each other both in the sense of providing information that cannot be procured at other levels and also in the sense of providing information that can limit the range of possibilities at other levels” ([

9], p. 174). He emphasizes that reduction alone cannot explain phenomena in which parts of a mechanism behave in a certain way partly because of their role in an integrated whole and partly because the whole most likely interacts with other entities ([

9], p. 183). A science dedicated to phenomena of various levels is thus needed: “Higher-level inquiries and reductionist inquiries complement each other, and often provide heuristic guidance to each other. Neither on its own suffices and neither can do the work of the other” ([

9], p. 193).

Complementarity of approaches is also crucially needed in examining how various forms or representations such as narratives affect us. Cognitivist film studies has focused on how certain formal features of a film generate certain responses in the spectator. At times this approach has quite unnecessarily been counterpoised against culturalist accounts of what kind of meanings films have had for spectators in various social contexts, not to speak of the hermeneutical project of interpretation. Here, again, we have an explanatory gap to bridge.

4. Existential Narratology

One of the major evolutionary advantages of humans is the capacity to create representations in our mind not only of how things are but also how things could be; not only to understand what is but also to fantasize about something completely different. On these lines, Donald E. Brown in his

Human Universals refers to research conducted by D’Aquili and Laughlin, who argue that by virtue of what they call the

cognitive imperative we humans are

driven to “organize unexplained external stimuli into some coherent cognitive matrix.” When the community cannot offer concrete causal explanations to phenomena, “first causes in the form of supernatural entities are generated” ([

10], p. 99). This typically takes the form of a narrative which suggests meaning that transcends immediate perception and understanding of reality within a symbolic sphere of some kind. It is important to appreciate that mythical stories or fiction in general are by no means inferior ways of modelling reality which in due course could be replaced by rational explanations about how things really are when viewed in terms of sober frame of mind. They are emergent phenomena which we humans use to explore, articulate, and enrich our experience of being-in-the-world. They do so by appealing first of all to our reason and pragmatic attempts at establishing a practical relationship with the world, but even more importantly by articulating our more ineffable existential concerns which fall beyond rationalizations. Psychology may offer convincing accounts as to what kind of cognitive functions trigger those concerns or attempts at coping with them, but it cannot offer much in the way of satisfying those concerns. Narratives have the ability to evoke responses at least in some of us that are every bit as important for our orientation into the world as are responses to concrete real life situations.

Referring to the primitive impulses behind our artistic and spiritual activities has become a commonplace in modern critical theory. Sartre for one came to the conclusion that we humans are pathological by nature, pathetically trying to suppress our awareness of our nothingness. In this view even imagination appears merely as a form of illness, or rather, like desperate clinging to a fundamental illness ([

3], p. 77). The opposite view emerges in Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy. In his view art emerges as a way of relating to nature only by transcending it ([

11], p. 78). It is about “the

coming to awareness by man of his own existence in the world”. Art participates in the growth of our self-awareness by articulating shades of experience, some of which thus become integrated into how we think and experience, how we recall and hope, the great moments of our lives as well as the texture of our daily lives ([

11], p. 81). Thus narratives have the capacity to exemplify both phenomenological and spiritual aspects of the human condition.

Torben Grodal has convincingly argued that certain traits that have evolved in the course of the development of mammals affect the kinds of narratives that we humans consume. For example, the instinctive tendency to take care of offspring is first of all an effective evolutionary strategy, which is given more specific manifestations within a given culture, often manifested in a moral code. However, it also creates a disposition to enjoy stories in which traits such as bonding, solidarity, and helping others loom large. Furthermore, as such dispositions inhibit certain other tendencies in human behaviour, conflicts arise which are negotiated not only in real-life terms but also in fictional narratives which are held to treat basic human issues ([

12], pp. 10–11). We have a need to ever deepen our understanding of the human condition and thus we are fascinated by stories that have existential relevance. Sad stories can be enjoyed, because they address the tragic features of life in a concentrated, focused way ([

12], p. 151). One might add that this is at once both something more and less. It may be inadequate as regards understanding the mental phenomena that is its root cause. However, it is also something lot more, as it contributes to the constituting of a human sphere of existence in which the workings of the mind are transformed so as to give rise to a spiritual level on which meaning is appreciated at face value rather as a symptom of complex cognitive functions. On its own, cognitive science or neuroscience can only explain how the system that makes all this possible works, and at the psychological level explain what kind attractors shape the formation of narratives as well as the fantasies to which they give rise. However, the socially shared existential content, which makes phenomena meaningful, simply lies categorically beyond its explanatory realm unless complemented by an appropriate culturalist account. The same applies to the notion of an imaginary sphere, the true meaning of which emerges only on the spiritual level.

The spiritual in art and entertainment works through maintaining the imaginary sphere from which it emerges: only with this buffer or filter against raw reality can there be something that may be called spirit. This is first of all because we need the imaginary to deal with knowledge and experiences too horrible or traumatic to be constantly maintained in consciousness. It need not be a question of ignoring these things, but rather of ensuring that one is able to maintain a sufficient mental distance so as not to be paralyzed by the horrible things one has learned about or has personally experienced. However, the imaginary also has the more affirmative function of allowing for the

seeing as mode to emerge, culminating in the spiritual capacities of being able to see something which transcends one’s or one’s community’s immediate self-interest, finding immaterial things as worth striving and even fighting for, seeing someone as eminently loveable, finding an abstract scientific discovery worth pursuing etc. The relationship between the imaginary and the spiritual may be seen as an instance of the self-taking into possession itself as an autonomous person carrying certain responsibilities toward its community, fellow individuals, and itself as a creature with certain past accountabilities, present responsibilities, and future commitments. The imaginary is also the psychological faculty which enables the level of spirit to emerge as upholding of faith in the possibility of meaning in the face of the meaningless cosmos or the indifference of much of the social sphere. It serves as an interface with others, including the “other” that is part of the structure of the self, allowing for needs and desires, emotions and responses to be exchanged, negotiated, and sublimated. It is a creative response to being, to perception and understanding. Frank Kermode writes: “… in ‘making sense’ of the world we still feel a need, harder than ever to satisfy because of an accumulated scepticism, to experience that concordance of beginning, middle, and end which is the essence of out explanatory fictions, and especially when they belong to cultural traditions which treat historical time as primarily rectilinear rather than cyclic” ([

13], pp. 35–36). Harder it may be, made even harder by the rhetoric of avant-garde which would do away with all such notions—but all the more important for that. We have every reason to think of narratives as

the technique of coping with temporal experience with all its philosophical and ethical underpinnings.

Fascination with existential issues can give rise to more complex forms of narration in which the treatment of existential issues rises to a new level. On the basis of a cognitive account, we may explore how stylistic features are used to create perceptual challenges which “activate[e] the brain to find more signs of hidden meanings than can actually be identified, and tend to articulate ‘lofty’, abstract, and allegorical meanings”. Depending on the narrative context this may even be experienced as sublime (12], pp. 106, 233). Moreover, narrative cum stylistic devices can be used to create a “

meaning effect”, i.e., to trigger the mind to seek for a meaning where there is none for the narrative to provide. Simply presenting counterintuitive events may produce this effect, provided, of course, that the overall narrative context supports the possibility of meaning ([

12], p. 149). As in the case of a metaphor, when an explanation in concrete terms is not available, the mind automatically seeks for a more abstract, or, “higher” meaning. This may be seen as a strategy by which we seek to articulate those existential questions which may have their root in the workings of our mind but which we are not able to conceptualize:

Art films express a key tendency in the evolution of the human mind: the increasing importance of the “inner” mental landscape brought about through a massive expansion in mental resources. Art films tend to focus on how experiences are processed in the inner world, as opposed to focusing on experiences in an exterior world. They use visual means to indicate abstract meanings, including stylistic devices aimed at making visual phenomena “special” and suggestive of higher meaning.

While we have to acknowledge reductively that an effect of higher meaning is achieved by certain formal means, we must also study the role of films, first of all, in constructing and maintaining a symbolic sphere of Žižek’s description, and then further explore how this can be reinterpreted as making existential sense. It is an interpretative task, and is no doubt best done by a critical mind aware of all the levels on which such effects are based. This approach considerably expands our sense and understanding of the various functions cinema and film have in our lives and in our societies. The conclusion the eminent scholars mentioned above have reached through analysing Pickpocket serves as an illuminating example of how delicate the balancing act between reductive and holistic accounts can be. However, this complementarity is needed in order to achieve a comprehensive understanding of how an art film such as Pickpocket is able to address key spiritual issues in a non-obvious fashion and actually suggest the possibility of restoring or maintaining faith.

5. Form and Faith in Pickpocket

David Bordwell has analysed in cognitive terms why many people experience Bresson’s Pickpocket (1959) as a religious film despite there being no explicit reference to religion or anything obviously transcendental. Before Bordwell, Paul Schrader also studied the formal structure of this as well as a number of other films in terms of his notion of “transcendental style in film”. He, however, discussed formal means as a way of treating something that by its very nature cannot be addressed directly. This approach connects in an illuminating way with the way Žižek employs the Lacanian notion of the “imaginary” as the mental faculty which allows us to take a certain distance from “raw reality” and adopt an attitude that allows for meaning to emerge beyond obvious rationalizations. Here, the imaginary is discussed in phenomenological terms as a way of treating on a psychological level what on an experiential level is described as a spiritual phenomenon, offering the possibility of experiencing its affirmation.

In his

Narration in the Fiction Film Bordwell offers a meticulous study of the subtle patterning of

Pickpocket in terms of what he has defined as “

parametric narration”. In this mode of narration, style is organized and emphasized to such a degree that it is at least as important as narration ([

14], p. 275). Bordwell analyses how

Pickpocket is so overwhelmingly full of stylistic patterns that it is impossible to assimilate it even on repeated viewings. Yet, it creates a sense of an order, which Bordwell characterizes as “

nonsignifying”. Because of this abundance of “order over meaning”, Bordwell refers to the film’s “stubborn resistance to interpretation”, claiming that interpretive analysis is not able to account for the most crucial features of this film ([

14], p. 306). Bordwell is not really interested in what happens to the characters and what kind of spiritual experience that could be taken to represent—the latter being a matter of interpretation, something that for Bordwell is at best subordinate to stylistic analysis. But even those of us inclined to making meaning in terms of human experience have to admit that interpretation is likely to remain shallow if it does not take into account the formal features through which that experience is represented in this particular film.

Toward the end of his analysis Bordwell argues: “Among other advantages, analysis of parametric form helps reveal the formal causes of that aura of mystery and transcendence which viewers and critics commonly attribute to Bresson’s work.” He emphasizes that any sense of transcendence here is merely a formal effect which can be explained in cognitive terms: “Because no evident denotative meaning is forthcoming from such obvious patterning, the viewer itches to move to the connotative level … Order without meaning tantalizes” ([

14], p. 305). This may well be so, but the question remains, does this reductive analysis exhaust the potential for meaning inherent in

Pickpocket? At the very least we should take into account the narrative framework within which we recognize certain human issues being treated and within which certain formal effects can have that causal effect on us which Bordwell so well describes. Crucially, the narrative in question is one of the type that in Kermode’s words is needed to counter the accumulation of scepticism—or, in terms of the present analysis, to counter lack of faith, succumbing to nothingness. Thus, we might do well to explore

Pickpocket, to borrow the words of W.C. Clocksin, as an instance of a legitimate way of “expressing the transcendent meaning and structure of the knowledge and concerns of all human beings” ([

15], p. 191).

In his

Transcendental Style in Film Paul Schrader analyses how Carl Dreyer, Robert Bresson, and Yasujiro Ozu use certain stylistic devices to make “the immanent […] expressive of the Transcendent” ([

16], p. 8). Transcendental style is most clearly evident in Ozu’s family-office cycle and Bresson’s prison cycle films [

17]. On the structural level this style consists of three steps: (1) The everyday: a meticulous representation of the dull, banal commonplaces of everyday living; (2) Disparity: an actual or potential disunity between man and his environment which culminates in a decisive action; and (3) Stasis: a frozen view of life which does not resolve disparity but transcends it ([

16], pp. 39, 42, 49). In Schrader’s view, elements such as plot, acting, characterization, camerawork, music, dialogue, and editing are not used to express anything, rather, their non-expressivity functions as a starting point of the transcendental style: “Transcendental style stylizes reality by eliminating (or nearly eliminating) those elements which are primarily expressive of human experience, thereby robbing the conventional interpretations of reality of their relevance and power” ([

16], p. 11). We may notice a crucial similarity in Bordwell’s and Schrader’s accounts: both focus on the formal structure and style offering something that defies ordinary responses yet entice the viewer to seek meaning, but the significance they assign to that quest differs wildly.

As Schrader notes,

Pickpocket is eminently suitable for demonstrating the workings of the transcendental style. The protagonist Michel displays hardly any feelings. He appears to live in a relentlessly bleak world, almost completely detached of normal human concerns. Only his mother’s death seems to elicit at least a slight emotional tremor in him, and only during one encounter with the police inspector does he briefly loose his nerve. He has an obsession, pickpocketing, which seems to subordinate all his other activities and human relationships. Success in this activity excites him, but this is only reported in his voice-over, never displayed. The spectator is invited to the share in this elation in an elaborate montage sequence in which Michel and two of his accomplishes are shown committing a series of thefts in a virtuoso fashion. Michel develops considerable skills, but admits that in the last instance he is at the mercy of chance. Clearly, he needs that excitement in order to ignore the spiritual void into which he has drifted. As Paulo Obada points out, right from the beginning the settings of the first two scenes, the hippodrome and the police station, stand for the opposition of chance and the rigidity of law ([

18], p. 25). At the very end of the film law prevails, but as if by chance a spiritual change takes place. Toward the end of the film Michel is caught and sent to prison. In his voice-over he expresses his loss of faith in life: “Why live?” However, the next time his girlfriend Jeanne visits him, “something illuminated her face”, he tells us in a voice-over, unexpectedly kisses her through the bars, and says: “Oh Jeanne, how long it has taken me to come to you.” Jean Baptiste Lully’s tender music breaks out to accompany Michel’s closing words, possibly addressed only to us [

19]. Depending on the spectator, this scene can be enormously effective, even suggesting transcendence (

Figure 5 at the conclusion).

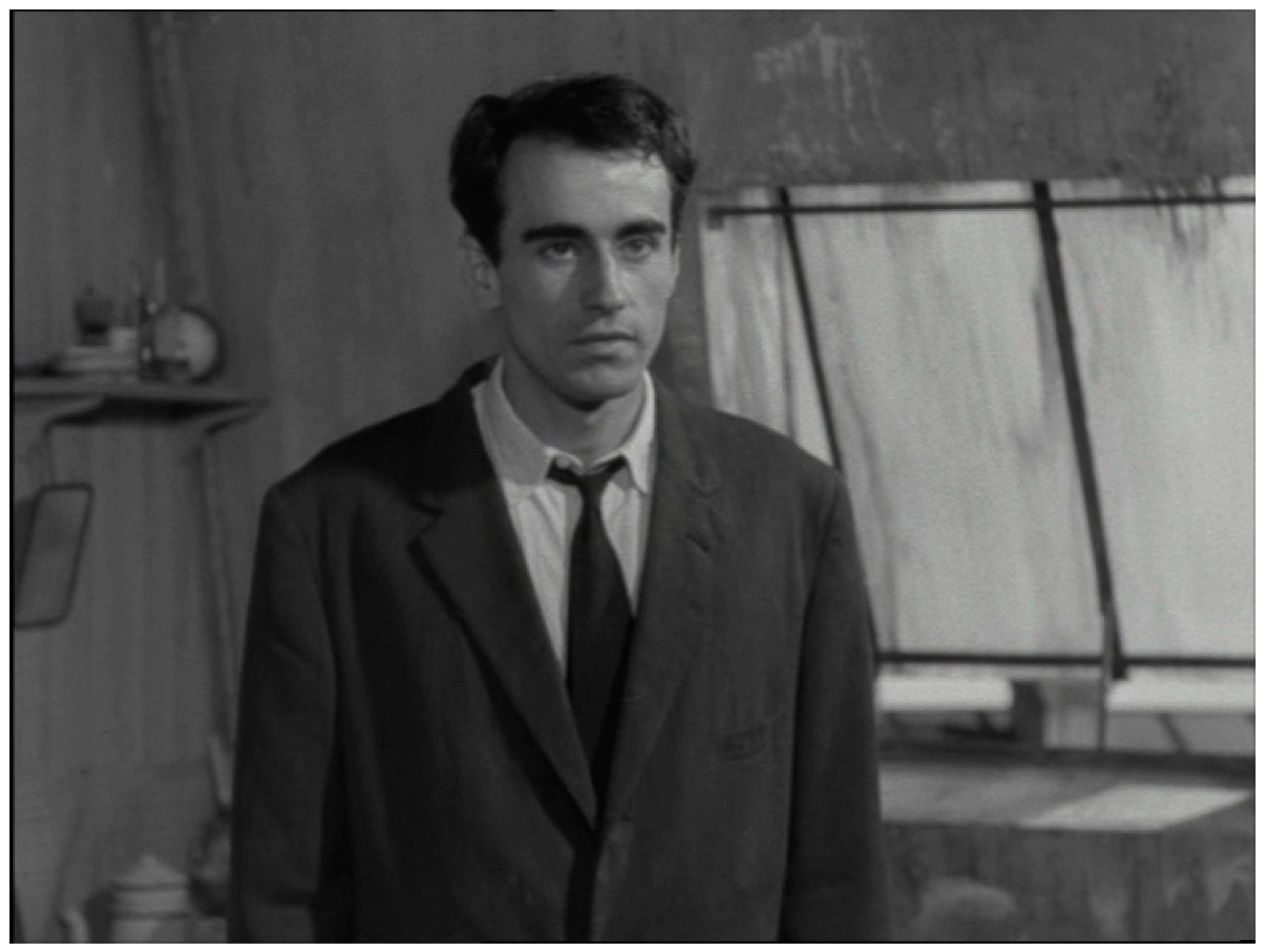

The efficacy of the process Schrader describes relies indeed on Bresson’s extremely controlled use of cinematic means: the slightly unnaturally restrained, decisively non-psychological acting which denies any easy point of identification, often highly elliptical narration, slow tempo, austerity of the sets, lack of establishing shots, tight framings and compositions, fairly static camerawork and repetitive or minimalistically varied patterns of découpage (

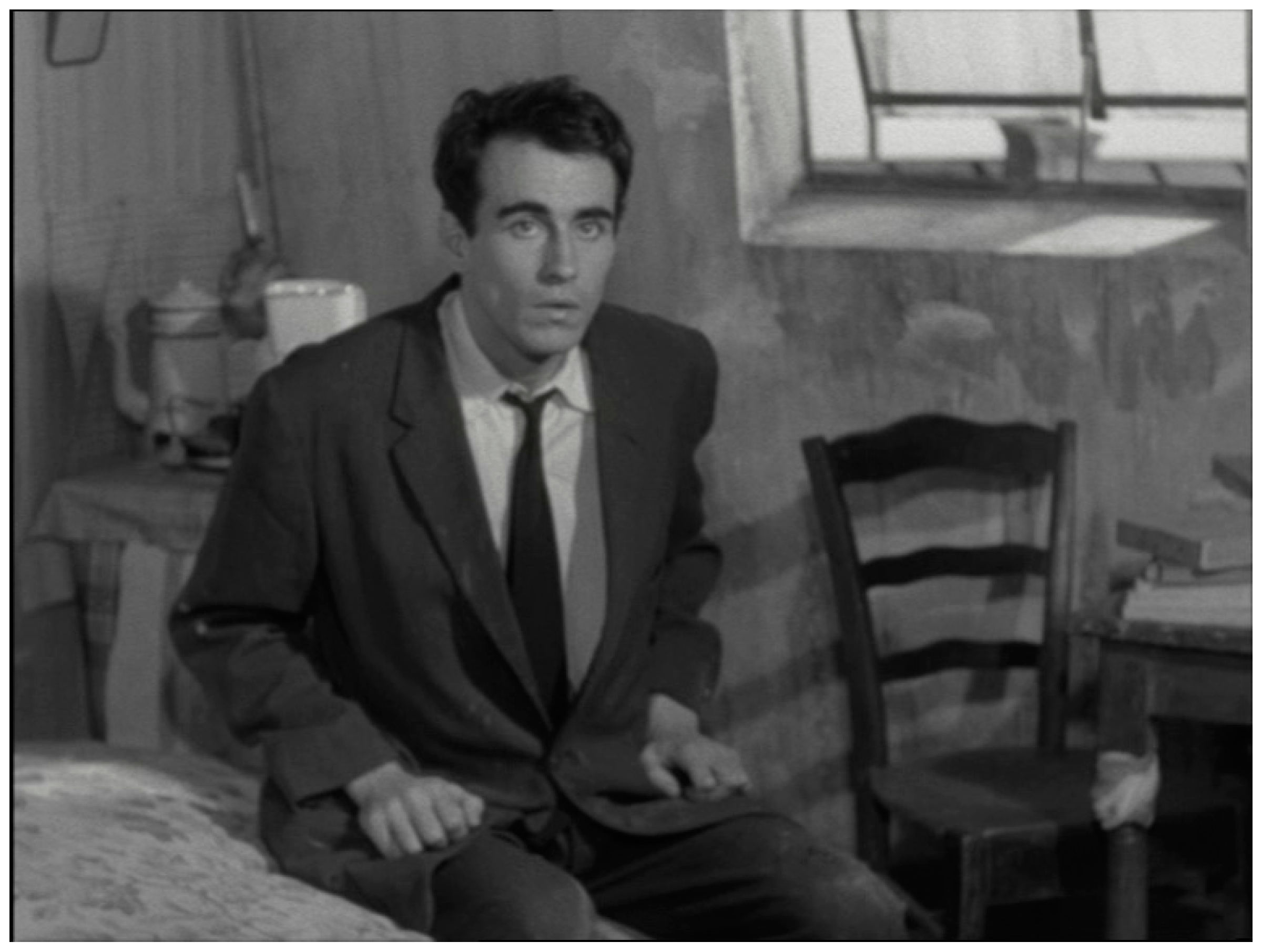

Figure 2). The soundtrack is equally carefully crafted. The concluding prison sequence is accompanied merely by the chilly sounds of openings and closings of the prison doors and the dull sound of footsteps in the corridors. We have reached the second phase of the transcendental style, disparity. Being confined to a prison cell obviously serves as a metaphor of existential separation, not being able to experience full togetherness with other people—a theme and variation of Bresson’s “prison tetralogy”, if not his entire cinematic output. Yet, recalling how limited Michel’s ability to interact with people closest to him has been throughout the film, it appears as if not being able to pursue his passion rather than confinement in itself makes Michel confront his existential vacuum. The austerity of the film’s style has the all-important function of making this Sartrean nothingness appear like genuine threat, making conscious existence appear as merely an epiphenomenon. Why live, indeed (

Figure 3). On the level of mere plot functions the answer is a melodramatic cliché: There is a person who loves you and loving her will give you the sense of meaning in life. The film does relate how such true love prevails despite adversity and even the failure to understand where one’s true blessings lie, but the formal features of the film save this narrative from lapsing into banality.

Schrader also points out that the potential effect of the film is achieved by means of formal repetition for which the spectator is not able to assign any precise meaning. Neither is the spectator likely to identify with Michel, although facing a similar existential question: wondering whether the process seen on the screen can really have any non-obvious meaning. Bresson does model an existential situation, but not by seeking to create an impression of psychologically rounded characters in a precisely defined social environment. Minimal cues suggest that Michel lives in Paris, but it is emphatically the Paris of dreary attic rooms rather than that of the great monuments, grand boulevards, and lovely parks (

Figure 4). The way Michel’s entries and exits from his minimally furnished bedsitter makes the passage to the street appear almost labyrinthine—the way entrances and exits from a visual theme and variations is one of Bordwell’s major examples of parametric narration in this film. Such parametric complexities are complemented by the subtle sense of tension that emerges from the extremely restrained fashion through which Michel’s pickpocketing is rendered. Although we are not cued to speculate whether he will succeed or not—already the opening text tells us that this will not be that kind of a film—we may still wonder what kind of an effect success or failure will have on Michel.

Michel’s reactions form the “strange paths, [which will bring] together two souls who otherwise might never have known one another,” as the opening text promises. However, rather than a plausible depiction of a psychological development, this narrative, in which characters with their traits in conjunction with the twists of the plot have certain precisely defined functions, serves as a fairly schematic demonstration of an existential possibility. The effect is further strengthened by what Bordwell calls “the ‘performed ‘nature of the découpage, whereby characters move into position of the shot/reverse-shot combination, as if figure behaviour and camera position secretly collaborated to fulfil an abstract stylistic formula” ([

14], p. 296). Similarly, the emphatically elliptical narration which may defy plausibility by letting events follow one another more quickly than they could possibly have happened (as András Kovács points out, Michel’s capture by the police at the beginning of the film could not take place within the timeframe implied ([

20], pp. 144–46), or refer to or merely imply leaps in time left accounted for (Michel’s two year stay in London). But above all, the essence of Bresson’s anti-psychological way of treating his characters lies in the abstraction of those human characteristics from which the trajectory announced in the opening text emerges.

Some spectators might not find Michel’s transformation at the very end of the film entirely plausible, but this would be an indication of an inappropriate way of following the narrative. Bresson is modelling only an abstract existential rather than a real life-like situation. The suddenness of this change of attitude has typically been interpreted as Bresson’s way of suggesting the work of grace. Some spectators might prefer an expression less loaded with religious connotations, such as a human encounter triggering the rise to a higher level of awareness opening a way out of a self-imposed psychological dilemma, but this is really beside the point. What matters is the notion of overcoming the intellectual and moral arrogance which blocks the possibility of human relationships—“I want no one, nothing,” Michel tells Jeanne when she first comes to see him in the prison. Bresson’s extremely controlled use of filmic means has throughout the film enforced a sense of spiritual confinement on the level of the world depicted, in which the spectator shares not so much through engagement with Michel but through the austere filmic texture on an obvious level on the one hand, and the controlled patterning of formal elements on a less obvious level on the other. As Schrader suggests, this economy of means enables a very slight gesture to have a profound effect, even to create the impression of a highly refined spiritual event, an establishment of a spiritual sphere which allows for experiencing something like a human encounter as a touch of grace. The final transformation does not resolve disparity, rather, it stands for accepting it: “If the viewer accepts the decisive action (and disparity), she accepts through this mental construct a view of life which can encompass both” ([

16], p. 82). In the last instance it is a question of having sensitivity for meaning that is not obviously there, that is merely suggested as something that by its very nature cannot be directly represented. Not everyone cares to embrace such a notion. Many people simply have no sense of the transcendental and are likely to find Bordwell’s analysis of the formal effect a sufficient explanation as to why

Pickpocket has such an impact on at least some of us—perhaps even on such sceptics themselves.

However, there is yet a third alternative that should be taken into consideration. In his analysis of Kieślowski’s

Blue Žižek discusses Julie’s quest as an attempt to regain a “fantasmatic frame that would mediate between her subjectivity and the raw Real” ([

21], p. 169). Žižek uses the word “fantasmatic” to emphasize that what is at issue is not something real, but rather a psychological construction that rises from a complex web of needs. A corresponding term which can be understood in more holistic way is the notion of “symbolic environment” or “symbolic sphere”, discussed briefly above. Julie has lost this after her husband and daughter have perished in a car crash, and with them her links with a symbolic environment that she needs to maintain a sense of meaning in life have been severed. Žižek’s notion becomes even more illuminating when “symbolic” is understood as “a legitimate way of expressing the transcendent meaning and structure of the knowledge and concerns of all human beings.” Thus, a symbolic sphere allows for inhabiting the real world as spiritual beings with the ability to extend outwards, toward other people, to one’s community, even the entire creation. This is something that can only be accepted by faith. Its opposite is negation, seeing oneself as an individual detached from the world and community at large, being void of a sense of values. In this light,

Blue is a story of how Julie gradually, in a paradoxical way, is able to recreate a symbolic environment for herself and thus regain her faith in life.

The notions of fantasmatic frame and symbolic sphere can equally well be applied to what happens at the very end of Pickpocket. The former carries more strongly the connotations of overcoming the sense of nothingness through a mental framework what can only be imaginary; the latter—according to the interpretation of the present writer—allows for conceiving of the imaginary as a very genuine dimension of human existence, as real as our material existence, only differently so. Pickpocketing seems to have been merely a fantasmatic frame that has prevented Michel from facing raw reality. It has given him a course in life, but merely as an obsession which creates a protective shield that actually prevents him from fully engaging with people nearest to him. By way of contrast, the final cinematic gesture is indicative of reaching the symbolic sphere as it stands for a sudden, inexplicable overcoming of the constraints that have prevented such engagement. These notions could explain in terms of the diegesis (i.e., in terms of the fictional world and its narrative logic) what takes place on the psychological level. Again, there are many who find psychoanalysis just as unpalatable as notions of transcendence, but even they may find plausible the notion that, as conscious beings, we humans must be able to maintain an ability for seeing and experiencing things as somehow significant rather than just raw, meaningless reality. Religion, art, party ideology, or a strong sense of belonging to a certain ethnic or social group may serve as frames within which a personal symbolic sphere may be constructed. This may take the form of someone just feeling he or she knows what to believe, how to behave and what to do in life. On a more sophisticated level, particularly as may occasionally be the case in connection with a work of art, this functions above all as a suggestion of the possibility of there being such a symbolic sphere which would enable maintaining faith in life. This may well be all the more efficacious if no declaration of faith is actually spelled out. When the narrative does not offer a framework within which the cognitive effect of Bordwell’s description could be easily fitted, the spectator has to draw on his or her spiritual resources to find a more or less clearly articulated interpretation for the experience the film evokes in him or her. This interpretation may be profoundly meaningful and resounding.

Thus, Bordwell’s analysis does not annul the point Schrader makes. He, too, discusses an effect achieved by certain aesthetic means, but focuses more on the overall pattern, which more obviously mirrors the human need for the kind of meaning that can serve as a foundation of faith. The difference of the status between these accounts is the scope of the cognitive effect to which stylistic patterning gives rise. While for Bordwell it appears to be something purely ephemeral that is better explained away, for Schrader employing aesthetic strategies in order to relate to things transcendental is as old as art itself—and still as relevant. Byzantine icons have had very similar functions in peoples’ lives, with their strict formalism having not only a certain psychological function but also, by virtue of that function, a certain meaning. We have to deal also with that meaning—irrespective of our ideas about transcendence—if we want to understand a work of art such as Pickpocket as a cultural artefact. Perhaps it is not a mere coincidence that Bordwell has written monographs also about Dreyer and Ozu—the same directors Schrader analyses under the aegis of the transcendental style. These are splendid examples of his scholarship but they take us only so far, they only reach a certain level in explaining how we relate to the films made by these directors. Higher levels of appreciation remain to be accounted for.

While Bordwell might well have written the point about clarifying mystifying notions about

Pickpocket with Schrader in mind—something that also Žižek might want to do following his own paths of reasoning—and although Bordwell and Žižek have fiercely attacked each other’s scholarly positions [

22], we should nevertheless ask whether their analyses and approaches really are mutually incompatible or whether they actually address different levels or aspects of relating to a cinematic work of art. In fact, the various issues to which films like

Blue of

Pickpocket give rise can all be placed on different levels as regards engagement with audiovisually represented fiction, ranging from primary perception through the narrative representation of orientation to a physical, social, and existential environment to the ways in which audiovisual representation can be used to refer and even maintain a symbolic sphere. The crucial factor that allows for this depiction is the bracketing of the psychological level to which the protagonist’s development could be reduced. As Schrader points out, it is left for the spectator to either reject or accept this suggestion of the transcendental.

Grodal’s approach is also quite compatible with Paul Schrader’s analysis. The difference, if there is any, lies in that for Schrader what Grodal refers to as meaning effect is a legitimate means of depicting transcendental experience—something that because of its ineffable quality cannot be referred to directly, only suggested in immanent terms. The crucial point is that we need (at least) these two levels of description, one by nature reductionist, the other holistic. Whereas on one level of description aesthetic strategies may be examined as triggering psychological processes by which a conscious mind responds to the need to experience its existence as meaningful and reasonably ordered, on yet another level this has irreducible qualities and validity which can be treated only within its own terms of reference. Thus, on this second level, the point is that the mind experiences the processes triggered in our brains by those aesthetic strategies as sensations of beautiful and sublime or transcendental meaning. The second level is fundamentally irreducible to the first in that the reality of existential content cannot be reduced to “lower” level processes which serve as its platform. From the existential point of view, such a reduction is simply beside the point. Clinging to such a reduction at the expense of treating the issues at hand in their own terms, their face value, so to say, is a sure indication of lack of understanding of how artistic devices can be used to symbolize or to model and articulate lived experience in a way that appeals both to our sense and senses. A holistic approach on the lines of Merleau-Ponty and Rauhala, on the other hand, without making any metaphysical claims, allow us to interpret a film such as Pickpocket in terms of a spiritual quest, awareness of the possibility of maintaining faith in the face of nothingness. It is left for the spectator to interpret this opening to otherness according to his or her own convictions, either as transcending the limits of the ego and opening oneself to otherness as the love of one’s fellow men, or something “wholly other”, a power experienced as overwhelming presence of God. The reductionistically-minded, overwhelmed rather by their faith in the power of reason, would be all too quick to give an explanation of the neurophysiology of either interpretation. Such extreme positions, due to lack of sufficient common ground in the form of existential experience or conceptual framework, are not negotiable. However, a philosophical position seeking a balance between reductionist and holistic accounts, the hermeneutics of suspicion and faith, at least creates an explanatory field on which the notion of transcendence can be legitimately posited, even if for some it will appear a bit too much, for others just too little.