Sensing and Longing for God in Andrey Zvyagintsev’s The Return and Leviathan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Manoussakis

2.1. Relational Theology

When we strive to redefine the person phenomenologically as prosopon, namely, as this coincidence of the phenomenon (essence) with phenomenality (existence), that is, a hypostasized ek-sistence, we have in mind nothing else but the event of the Incarnation. Pace Heidegger and St. Thomas, we do not think that God’s self-hypostasizing of His existence should be mutually exclusive of man’s potential of transcending his nature by choosing to be (and become) who he is. If man can exist as a person (which is what Heidegger claims concerning the Dasein), that is because God (the person par excellence) became man.([4], p. 31)

2.2. Manoussakis’s Methodology in the Context of Contemporary Phenomenological Film Studies

...[T]ouch is not about ownership or complete knowledge of the other, but is truly intersubjective. Just as, in the exchange of glances with an other, we can see ourselves seeing, in the contact of our skin with another’s, we can feel ourselves feeling. We feel ourselves as if for the first time in that moment, and as if from an external “point of touch”.([11], p. 35)

3. “Seeing” through Not Seeing: Visuality, Negation, and Space

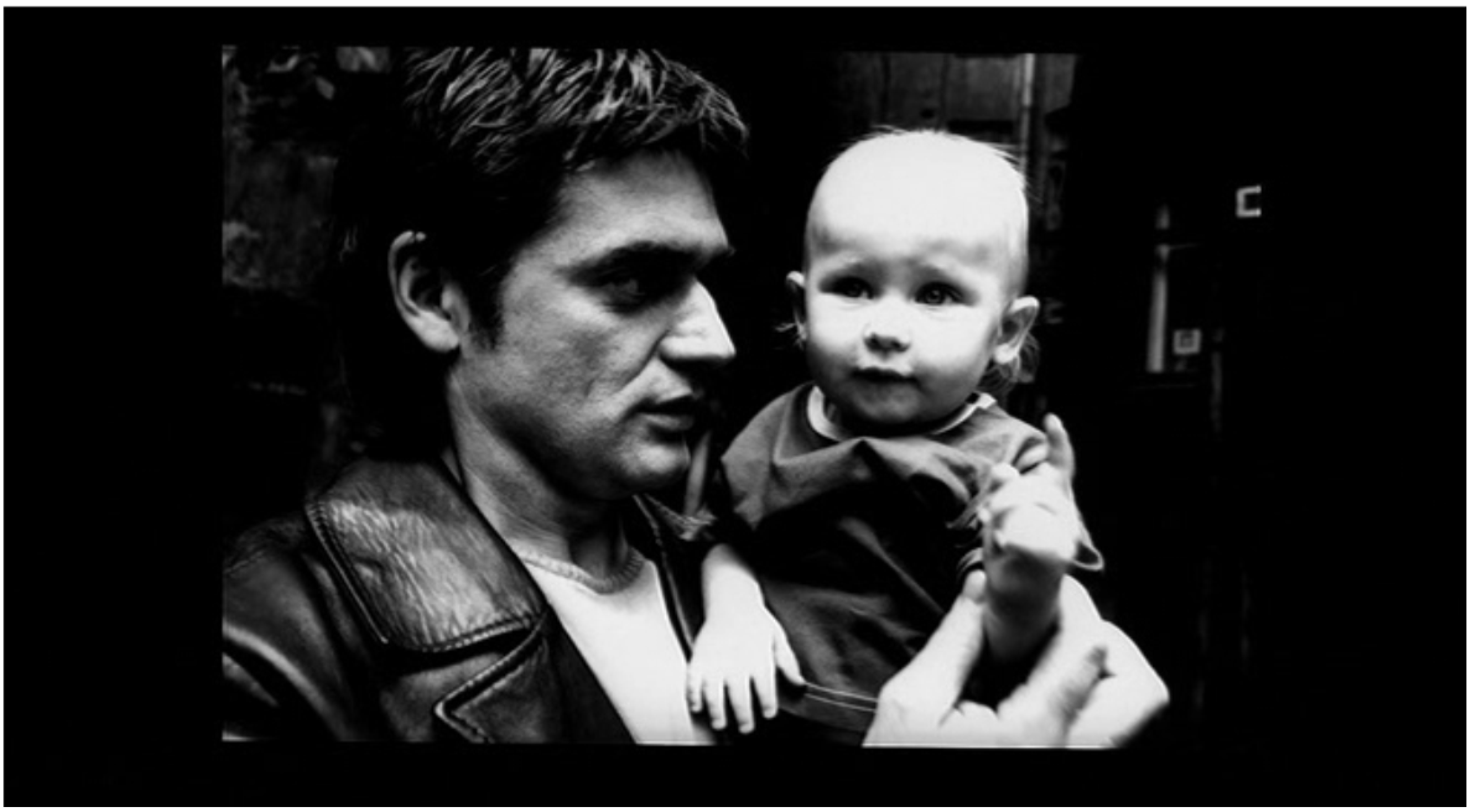

3.1. The Return

3.2. Leviathan

4. “Hymn”: Hearing and Time

Thus, it is not we that expect a phenomenon or even the other/Other, but this other/Other that challenges us to discover ourselves.When this happens, when my perspective is countered, inversed, returned to me, I am no longer the privileged subject that establishes and constitutes the objectivity of the world (the thinghood of the things), but merely a dative; I become this “to whom” the world, as the world-to-come, is given. For only then can there be a world given, when I make myself available as a receiver, as gifted (l’adonné) with the gift of givenness.([5], p. 67)

4.1. The Return

4.2. Leviathan

5. “Touching Itself”: Self-Perception and “Haptic Knowledge”

When, then, the soul is compared to the hand, much more is said about the soul than what, we might, at first glance, think to be the case. For in “touching” the things it seeks to know, the soul-hand is also “touched” back by the world. As “touched”, in the act of comprehending, the soul becomes aware of itself. It becomes aware of itself as a soul that “touches” the world. This self-awareness achieves the impossible—for it could be said that in some sense the soul, aware of itself as a soul, is touching itself.([5], p. 127)

5.1. The Return

5.2. Leviathan

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Julija Anochina. Dychanie Kamnja: Mir Fil’mov Andreja Zvjaginceva: Sbornik Statej i Materialov. Moskva: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Andrey Zvyagintsev. The Return. Berlin: Kino International, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Andrey Zvyagintsev. Leviathan. New York: Sony Pictures Classics, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- John Panteleimon Manoussakis. “Toward a Fourth Reduction? ” In After God: Richard Kearney and the Religious Turn in Continental Philosophy. Edited by John Panteleimon Manoussakis. New York: Fordham Press, 2006, pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- John Panteleimon Manoussakis. God after Metaphysics: A Theological Aesthetic. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Charles M. Stang. “Being Neither Oneself Nor Someone Else: The Apophatic Anthropology of Dionysus the Areopagite.” In Apophatic Bodies: Negative Theology, Incarnation, and Relationality. Edited by Boesel Chris and Keller Catherine. New York: Fordham University Press, 2010, pp. 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Vivian C. Sobchack. The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vivian C. Sobchack. Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004, pp. 302–3. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph G. Kickasola. The Films of Krzysztof Kieślowski: The Liminal Image. New York: Continuum, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- David Morgan. The Embodied Eye: Religious Visual Culture and the Social Life of Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012, pp. 177–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jennifer M. Barker. The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- John Panteleimon Manoussakis. “Theophany and Indication: Reconciling Augustinian and Palamite Aesthetics.” Modern Theology 26 (2010): 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Luc Marion. In Excess: Studies of Saturated Phenomena. Translated by Robyn Horner, and Vincent Berraud. New York: Fordham University Press, 2002, pp. 113–19. [Google Scholar]

- Søren Kierkegaard, and Lowrie Walter. Fear and Trembling and the Sickness unto Death. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013, p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Andrey Zvyagintsev. Elena. Moscow: Non-Stop Productions, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosios Giakalis. Images of the Divine: The Theology of Icons at the Seventh Ecumenical Council, rev. ed. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2005, pp. 59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Denis J. Bekkering. “Leviathan.” Journal of Religion & Film. 2015. Available online: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol19/iss1/45 (accessed on 25 September 2015).

- John Panteleimon Manoussakis. “The Promise of the New and the Tyranny of the Same.” In Phenomenology and Eschatology: Not yet in the Now. Edited by Neal DeRoo and John Panteleimon Manoussakis. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate, 2009, pp. 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- 1If the Mantegna painting suggests that God is revealed in death (and, presumably, resurrection), the Bible illustration suggests the encounter with God can be terrifying, and deliverance may only come unexpectedly. In the film’s most climactic scene, Andrei screams that the father wants to kill him, provoking the father to grab an axe, hold it over him, and ask if he “really thinks so”. And, yet, thematically, it is Ivan who is in danger of actually being “sacrificed” (ready to jump from a watchtower) and eventually saved by the Father’s efforts. This may remind us of Søren Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling, where he states that Abraham first appears as a murderer, not a hero of faith, but the story requires a perspective of faith to be understood properly. Indeed, the whole story could be seen as a passion event of Abraham, bringing even more parallels to Christ into this context [14]. The Father, perceived as a monster, is truly a hero. Therefore, visual citations of death and sacrifice in religious art suggest we view the boys’ experience as an experience of God.

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kondyuk, D. Sensing and Longing for God in Andrey Zvyagintsev’s The Return and Leviathan. Religions 2016, 7, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7070082

Kondyuk D. Sensing and Longing for God in Andrey Zvyagintsev’s The Return and Leviathan. Religions. 2016; 7(7):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7070082

Chicago/Turabian StyleKondyuk, Denys. 2016. "Sensing and Longing for God in Andrey Zvyagintsev’s The Return and Leviathan" Religions 7, no. 7: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7070082

APA StyleKondyuk, D. (2016). Sensing and Longing for God in Andrey Zvyagintsev’s The Return and Leviathan. Religions, 7(7), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7070082