Abstract

The cinema of the Dardenne brothers represents a new kind of cinema, one that challenges a number of our conventional ways of thinking about the distinction between religion and secularism, belief and unbelief. Their films explore the intricacies of spiritual and ethical transformations as they are experienced within embodied, material life. These features of their cinema will be examined primarily through the lens of Emmanuel Levinas’s philosophy of the imbrication of the drama of existence and the ethical intrigue of self and Other. The work of the Dardenne brothers can be understood as an attempt to express what I describe as a “faith without faith”—a recognition of the absolute centrality of belief for the development of a responsible subject but in the absence of a traditional faith in a personal deity.

1. Introduction

The films of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne represent a new kind of cinema that forcefully captures our current existential and spiritual state of affairs1. I contend that the power of their films derives from an awareness of the necessity for transcendence in a time when traditional, institutional religion appears incapable of addressing that very need for significant numbers of people in the western world. Their films can be conceived as attempting to perform a task formerly carried out by means of explicitly religious rituals and practices.

How we characterize what is “new” in their cinematic philosophy, however, is critical. One needs the right words to describe what is at play in their work. Some critics and commentators have been justified in recognizing the persistent presence of religious themes in their films—beyond the very secular surface that we first encounter on the screen. Attentive viewers will undoubtedly notice the many allusions to biblical sources in those films2. Without careful qualification, however, the term “religious” is simply misleading. We are fortunate to have at our disposal a number of illuminating interviews that one or both of the brothers have given over the years. In addition, we now have ample written material, in particular, from Luc Dardenne about the significance of their art3. His written reflections reveal a genuine preoccupation with religion, but from the standpoint of someone who grapples with the question of the death of God. Indeed, that theme is repeated so many times in his most recent work that a superficial reading of that text might lead one to think that we are dealing with a straightforward atheistic view of life. He himself recently admits of having no faith in a personal God. However, the simple epithet of “atheist” is as problematic as “religious” in this context. When asked about his own relation to faith, his response puts us on notice that this is no simple atheism: “that does not mean that I cannot speak about God, or that I cannot feel a relationship with such a Being that does not exist”4 The religious impulse goes to the heart of what it means to be human, for him, and, presumably, his brother5—even if, at the end of the day, he, admittedly, lacks faith in the personal God that is attested to in the monotheistic traditions. The Dardenne brothers’ films, I maintain, take religious experience seriously but beyond the traditional and conventional ways that we conceive of the dichotomies of religion and secularism, belief and unbelief.

In an effort to better understand what is at stake in their remarkable work, I will make special use of the philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas. Much has already been said about the obvious links between Levinas and the Dardenne brothers6. My own distinct approach frames that relationship in terms of Levinas’s depiction of the imbrication of two dramas that are at play in human life. That framing, I hope, can shed further light on the brothers’ highly original cinematic style—one whose phenomenological reduction (it is not a stretch to call it that) has the capacity to reveal what is most hidden in the drama of existence and the ethical relation with the Other. Finally, Levinas also provides us with a useful way of positioning their aesthetic production with respect to the question of faith.

2. Levinas and the Invisible Drama of Self and Other

One would be hard pressed to find a more felicitous coupling of film and philosophy then the relationship that conjoins the cinema of the Dardenne brothers and Levinas’s thought. What makes this particular pairing between philosopher and artist so fruitful is the fact that the filmmakers in question are intimately familiar with Levinas’s ideas. Luc Dardenne, who pursued graduate level work in philosophy, studied with Levinas when he was a visiting professor at the University of Louvain. The filmmaker explicitly acknowledges the brothers’ indebtedness to Levinas’s philosophy in various interviews and in his books. However, before discussing their work, I want to briefly sketch some of the basic attributes of what, for Levinas, constitutes the human drama and how art either neglects or distorts these features.

The human drama, for Levinas, is comprised of two separate but related dramas7. The first drama concerns our relationship to being or existence. Levinas refers to this relationship as the “drama of being” ([10], p. 40). This drama is primarily characterized by the self’s precarious place within being. For Levinas, the self is an ontological point or moment that temporarily arrests the flux or indeterminacy of being, what he calls the il y a or “there is.” The il y a, for Levinas, represents being in its most diffuse state, existence shorn of all determinations or thingness. Its biblical corollary is the tohu wa bohu of Genesis 1:2; the formless and empty darkness out of which a world eventually emerges. Despite its accomplishment, the fact that it has staked out a place within the impersonal murmur of being, the self is nevertheless constantly threatened by the possibility of being undone by the diffusiveness of the il y a. Levinas describes the il y a as threat, but also as a site of fascination for the self. The fascination has in large part to do with some of the extreme states that the il y a can give rise to. When in the grip of the il y a, the boundaries of selfhood begin to dissolve giving rise to intense affective paroxysms. In 1947, Levinas observes that when the ego is under the spell of the il y a it is “submerged by the night, invaded, depersonalized, stifled by it” ([11], p. 58). These liminal states create the impression of a kind of transcendence, relief from the burden of existence. For Levinas, however, this impression is nothing more than a powerful illusion. For the impersonal and anonymous experience of the il y a only serves to confirm the ubiquity of being, its vice-grip hold on the self. Far from offering freedom from being, the il y a represents for Levinas the “no exit” par excellence. Put otherwise: there is so proper solution to the problem of human existence from within the strict parameters of being itself.

The existential desert of the il y a represents, for him, the antithesis of human encounter and solidarity. The drama of being unfolds within an anonymous space devoid of an accountable “I” who can genuinely express “here I am”8 in response to the ethical demands of a “You” who stands before it. As far as Levinas is concerned, the only genuine site of transcendence is to be found in another drama, one that his later work refers to as the “ethical intrigue” ([12], p. 200). With this second drama, another figure appears on the scene: the Other—and with, the Other, a hint or trace of the divine also makes itself known. Levinas’s mature work attempts to describe the nature of the invisible drama that draws together self, Other, and an ever-receding Wholly Other who we are constantly in danger of ossifying or idolizing as a result of the inevitably self-limiting nature of names and concepts. As a way to avoid this danger, Judaism has a long-standing tradition of proliferating the names for the absolute Other. Levinas repeats this gesture in his own writing, employing, as he does, a multitude of names for this third party within the ethical drama of human existence: the traditional designation of “God”, the philosophical term “Infinite”, and even neologisms like “Illeity”. It is critical for Levinas that we avoid focusing on this third at the expense of the other parties that make up the ethical intrigue. The encounter with the human Other gives rise to what Levinas calls the “idea of God that comes to mind”—a jarring awareness that something greater, Infinite, breaks through in that encounter, but which simultaneously removes itself from my reach. As such, for Levinas, talk of “God” is legitimate only within the context of the asymmetrical relationship between myself and the flesh-and-blood Other who, from an ethical perspective, always has the upper hand over me. “Ethics is not the corollary of the vision of God”, the Jewish philosopher states, “it is the very vision. Ethics is an optic, such that everything I know of God and everything I can hear of His word and reasonably say to Him must find an ethical expression” ([13], p. 17). The Other impinges, breaks through with her ethical demands, before I have had an opportunity to respond or make sense of her. It is in that relationship that I am left with a trace, a hint, of a force that we can legitimately—but always with the utmost caution—name “God”.

Ethical substitution—one of the central concepts of his later philosophy—is meant to capture the peculiar relation that is established between myself and the others in my midst. For Levinas, the other human being has the remarkable capacity to morally interrogate my existence. The Other accuses me, challenges me, and makes seemingly infinite demands on me. These actions on the part of the Other are not initiated by the self. That is, left to ourselves, we would gladly pursue our own selfish desires. However, the Other will not have it that way. She questions my very attempt to establish myself as the center of my reality. There is a kind of displacement that transpires when we encounter others. Our entire focus shifts—from self-concern and self-preservation—to a responsiveness that is reoriented outside of the self. This displacement is so radical at times that the self finds itself seemingly occupying the Other’s place. I can feel so utterly obligated towards the Other as to literally feel that I have been taken hostage by him or her. This is what Levinas means by “substitution” [14]. For Levinas, ethical substitution is at the heart of our humanity. If the Other lacked this capacity to alter our way of being in the world, we would be condemned to the meaningless vagaries of the il y a as well as to a state of perpetual war, that is, an endless, futile battle of ego against ego. As a result of the ethical drama, the threat and fascination of the il y a within the tragic drama of being provisionally loses its grip on the human imagination, to be replaced by the promise of hope, frankness, and responsibility.

The nature of ethical substitution is such that it powerfully suggests, for Levinas, a connection between the other human being and the divine or Infinite. That the Other can make the self morally question its place under the sun and can do so by short-circuiting the cogito’s representational and rationalizing capacities suggests to Levinas—adapting a famous expression of Plato’s—the trace of the good beyond being. This insight receives, for Levinas, its first major articulation with the advent of Judaism. The Jewish scriptures identifies the essence of the divine with an obligation to look after the “widow”, “orphan”, and “stranger”, that is, the most vulnerable in society (for example, Deut. 10:18). The New Testament extends this view, for example, in the admonition that if religion has any authentic significance, it does so, not as a set of badges that one wears to publicly express one’s supposed religiosity, but rather in one’s ethical comportment, and specifically—repeating almost word for word the earlier Mosaic demand—in one’s responsibility “to look after orphans and widows in their distress” (James 1:26–27). For Levinas, the ethical commandment that comes from the Other highlights the revelatory nature of ethics. By emphasizing the exteriority of the call, ethics for Levinas is itself a kind of religious encounter, albeit invisible. For, as Levinas sees it, the trace of the divine always already recedes from the ethical relation even as it underwrites the relation as such.

Given Levinas’s emphatic position that what is essential to the human drama remains invisible to the phenomenological gaze, it would seem that art and its various methods of representation cannot do justice to the religious or spiritual background of the ethical intrigue. An initial reading of Levinas’s most well-known statement on aesthetics, his 1948 essay “Reality and its Shadow,” would strongly suggest that not only can art not do justice to the human intrigue, but that it will inevitably distort and displace what is truly at stake in that intrigue. In this essay and later in Totality and Infinity, Levinas maintains that art substitutes façade for the face, illusory spectacle for the provocations of the ethical intrigue. “Reality and its Shadow” decries the image as that which “marks a hold over us rather than our initiative, [it is] a fundamental passivity” ([15], p. 132). The image, Levinas goes on to say, is a form of “incantation”, a primal rhythm that possesses the subject, rather than a mediated concept that maintains a critical distance from the object to which it refers. What seems most vexing for Levinas is the capacity for the image to disengage us from reality, to obscure the exigencies of material existence. Art, for Levinas, belongs to a realm prior to creation, where indeterminacy rules and subjectivity has yet to emerge or has been eclipsed. The plasticity of art, in other words, transports us to the inhuman realm of the il y a. Its lifeless images point to other formless images and away from the ethical intrigue. In this way, art shares the same nature as the hallucinations that possess the self when it finds itself in the grip of the il y a. In short, the aesthetic experience could not be further removed both in practice and in the content that it divulges from the ethical encounter of self and Other. Levinas does not limit these critical remarks to the plastic arts, but extends them to include “music, literature, theatre”, and, not surprisingly, “cinema” as well ([15], p. 139).

But is this the entire story? Is Levinas’s final view then that art—cinema included—is fundamentally irreconcilable, even in conflict, with the spiritual and ethical truths of human existence? To get beyond the impasse that such an interpretation leads to, it might be useful to keep in mind a couple of points concerning Levinas’s critique that have already been foregrounded by commentators like Richard Kearney [16], but which bear repeating in this present context. First, Levinas, much like Plato before him, and with whom he is often linked on this issue, does not condemn art tout court as much as challenge some of the more grandiose claims that are made on its behalf. In this respect, art, Levinas states categorically in “Reality and its Shadow”, is “not the supreme value of civilization” as some would have us believe ([15], p. 142). The second point is that Levinas’s privileging of criticism over art does not rule out the possibility that the artist and the critic can be one in the same—a claim that is touched on towards the end of “Reality and its Shadow”, and developed further in his subsequent essays on aesthetics. In later essays on writers like Celan and Proust [17], Levinas expresses his praise for a form of literature that calls into question the very illusory trappings of art. Such art is sometimes deployed in the service of drawing our attention to both the ethical demands of the Other and the ways that we evade them. Of course, even if we acknowledge the possibility of an ethically oriented literature in Levinas’s thought, the question still remains as to whether or not the same can be said of cinema. There are so few references to cinema in Levinas’s work as to make it impossible to definitively answer this question on the basis of textual evidence alone. However, it might not be so difficult for us to imagine what such a redeemed cinema might resemble. Certainly, the history of cinema criticism provides us with some possible examples, including two from the list of great luminaries of film theory: Siegfried Kracauer and André Bazin. When Kracauer declares that the technical features of film must be deployed in the service of the camera’s capacity to record reality [18], it is impossible to miss the ethical imperative behind his claim. For Kracauer, film should be a form of truth-telling. The ethical and spiritual force behind Bazin’s theory of realism is likewise evident. Bazin describes the realist filmmaker’s vocation as one of love for the reality he or she captures with the camera.

The Dardenne brothers undoubtedly could be added to this list of filmmakers who demonstrate a genuine compassion for their characters or subjects. I also suspect that Levinas would regard the creative efforts of his former student and his brother as a redemptive form of cinema, one that grapples with the essentials of the human drama.There is no way of completely understanding the art of Flaherty, Renoir, Vigo, and especially Chaplin unless we try to discover beforehand what particular kind of tenderness, of sensual or sentimental affection, they reflect. In my opinion, the cinema more than any other art is particularly bound up with love.([19], p. 72)

As deeply engaged and responsible filmmakers, the Dardenne brothers consciously employ the tools of cinematography not to dazzle their audience, but rather to capture what defines us as both individuals and partners in the human intrigue. In this regard, the brothers are very aware of how images when treated for their own sake can, and most certainly do, traffic in the inhuman nature of indeterminate being. Thus Luc Dardenne writes in his diary:

Many hours spent in front of a television screen: broadcasting a neutral, muted flux, a continuum that envelops, an indeterminate presence that numbs. A state of torpor that closely resembles what Levinas writes in relation to the il y a, the murmur of being. No word, no sound, no image can bring this state to an end…To drown in the flux, in the density of the void…that is the deep desire of the telespectator…([2], p. 59)

To this use of imagery, which is of course not limited to the moving images of television but is equally present on the screens of movie theatres, Luc Dardenne counterpoises another type of image, one that speaks to the ethical intrigue rather than to the seductive deluge of vapid, amorphous images which have the power to seize us and pull us back into the void of the existential wasteland of the tohu wa bohu.

3. Faith without Faith: A Postsecular Cinema

The Dardenne brothers, I maintain, offer us an excellent example of an ethical cinema—one that tracks the key contours of the ethical intrigue and the perils of the drama of being wherein the ego takes flight into the seductive allure of anonymous existence. Like Levinas, they too share an apprehension of the image9, of its propensity for the inhuman. The brothers charge themselves with the demanding task of representing the ineffable features of our humanity. The desire to represent the deepest aesthetic, moral, and spiritual dimensions of the human being seems further complicated, even insurmountable, in the case of artists whose vocation is cinema. If the prohibition of the graven image means that the static image is minimally met with initial reservation, then it is doubly so with the moving image. Cinema’s capacity to reflect back both the surface and movement of reality makes it an even more powerful tool of enchantment and sorcery. The consternation with the image is intensified in the case of film, because cinema’s formal features (i.e., special effects, montage, etc.) make it possible to graphically render the contents of the world as well as the human imagination in spectacular and mesmerizing ways. Although, as Bazin, amongst others, points out, cinema is at the same time remarkably well suited to give testimony to experiences that often elude other media.

Rejecting the idea of creating images for their own sake or for the purpose of enchanting an audience, the Dardenne brothers have set for themselves the alternative task of offering testimony to the human condition and in particular to witnessing the ethical intrigue. Over the past two decades, they have created films that attempt to represent the transformative possibilities of ethical substitution. Their distinct camera work can be conceived as a meticulous spiritual exercise, one which permits them access to phenomena and experiences that otherwise fail to register in our minds. The use of the term “spiritual” in this context is not contrived. The Dardenne brothers are not averse to using that language themselves to talk about their work. As they note in one interview “perhaps filming gestures and very specific, material things is what allows the viewer to sense everything that is spiritual, unseen, and not a part of materiality” ([21], p. 132). The movement of their camera is painstakingly attentive to the materiality of the world—in the service of showing what otherwise might go unseen: “[w]e tend to think that the closer one gets to the cup, to the hand, to the mouth whose lips are drinking, the more one will be able to feel something invisible—a dimension we want to follow and which would otherwise be less present in the film” ([21], p. 132). Developing this observation in greater detail, Luc Dardenne, in one of his most perceptive film journal entries, notes:

The movements of our camera are rendered necessary by our desire to be in things, inside the relations between glances and bodies, bodies and scenery. If the camera films a body in profile, immobile, with a wall behind it, and if this body begins to walk along the wall, the camera will go there, passing in front of the body, slipping between the wall and the body making a movement that will frame the body in profile and the wall behind it, and then the wall and the body…([2], p. 138)

We immediately recognize in these words a succinct description of one of the hallmarks of their cinema. Their distinctive way of tracking the human body is evident from La Promesse (1996) [22] onwards. It is especially pronounced in Le Fils (2002) [23] in which most of the narrative telling is communicated through the presence of the body rather than the manipulation of narrative temporality, that is, montage. A brief analysis of the opening sequence reveals the intricacies of their cinematic style. The body is the precise starting point of the film just as the title credit appears. After a few seconds of the black backdrop of the title credit that first appears we suddenly realize that what we are actually seeing is a darkened, extreme close-up of the protagonist’s back. From that moment onwards, the camera meticulously trails every movement of Olivier’s restless body. This often produces the impression that the camera is always just catching up to his corporeal shifts and turns. This approach to filming the human body is established in the opening shot of the film. It is maintained for the duration of the film. In the opening seconds of the film, as the camera slowly moves away from his back, it gradually shifts upwards to shoulder level. We now see the back of Olivier’s head and neck (Figure 1). From there, it pans leftward, revealing in the process a middle-aged woman (Figure 2). The camera then pans rightward, returning to the previous vantage point directly behind his head and neck. It then moves slowly down following the contours of his left arm and stops to show us that Olivier is holding a document (Figure 3)—presumably something that was just handed to him by the woman. We are always just an arm’s reach away from the objects and people in Olivier’s immediate environment. A minute later—after a brief interruption involving a malfunctioning circular saw—we are made to appreciate, again through his bodily gestures, that the document communicates something jarring (Figure 4). The body registers an apprehension. The camera moves in even closer. Olivier’s troubled face fills the screen in profile. And while he continues to move the camera suddenly stops. The face of the woman who just a moment or two earlier stood before him now occupies the frame (Figure 5). The expression on her face mirrors Olivier’s consternation. Like this sequence, the rest of the film intimately follows the motility of Olivier’s body as it contends with its ever-dynamic environment.

Figure 1.

Opening Sequence of Le Fils.

Figure 2.

Opening Sequence of Le Fils.

Figure 3.

Opening Sequence of Le Fils.

Figure 4.

Apprehension.

Figure 5.

Apprehension.

What motivates this “desire to be in things”? Luc Dardenne poses this very question: “Why this desire that my brother and I share absolutely? Why don’t we keep our distance from bodies…?” Reflecting as he does on the intensity of their camera’s attentiveness in relation to the phenomena at hand, the Belgian cineaste, directs his self-questioning specifically to the human subjects that their films track with unrelenting dedication. “Why these solitary, uprooted, nervous, bodies…?” And, furthermore, why, he inquires, do the brothers not film these bodies at a distance? To which he confesses that he and his brother, of course, “would like to…but something in us resists that”, and compels them, instead, to do otherwise. And, then, finally, an admission of what is to be found “inside” those things and bodies. “Perhaps it’s because we find there”, he continues, “close to things, between bodies, a presence of the human reality, a fire, a warmth that irradiates, that burns and insulates us from a sadness that reigns in the void, the very great void in life. It is our way of not despairing, to have faith again” ([2], pp. 138–39). Rather than adopting the safety of distance which their lens afford them, their camera, instead, consciously plunges into the very being of their subject matter, inhabiting it in much the same way that meditation requires one to be present to intrusive or even painful thoughts and sensations, rather than to flee them, as we are all want to do.

The materiality that the brothers have in mind is not the crude sort that is often peddled by reductive materialism. There is an irreducible depth in material existence. Disrupting the drama of being—at the material level of vulnerable, exposed bodies encountering one another—is the ethical intrigue. Again, Levinas seems to be a major influence here. In the final phase of his philosophy, Levinas prefers the term proximity to his earlier invocation of the face. The face he had insisted on earlier is not simply what we see, its plasticity. There is “more” to the face, a surplus beyond what is observed by our senses. As a result of repeated misunderstanding, Levinas began to employ “proximity” as a way to suggest a form of irreducible presence to our embodied life—that marks a paradoxical experience that is at once near and intimate but simultaneously far (in the sense that it is outside my capacity to control) and strange—that yet exceeds my capacity to master it. No matter how much I try, I cannot assimilate the excessive surplus of the Other’s proximity. The Other’s irreducible strangeness unsettles me, pulls me out of myself, denudes me, exposes me, turns me inside out.

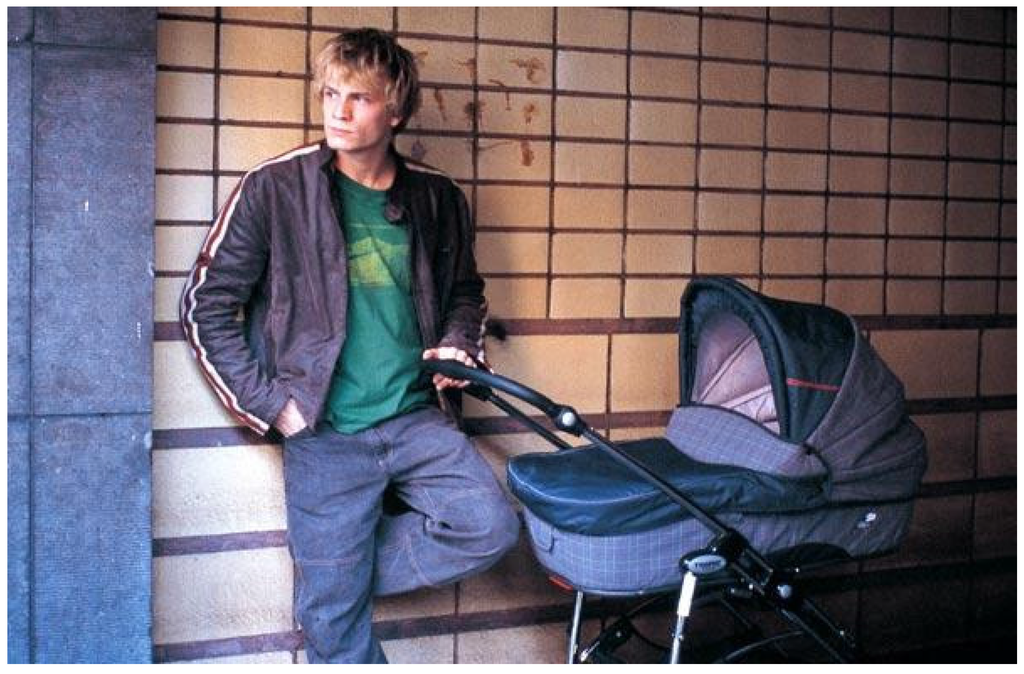

The debt owed to Levinas can be seen in a number of their films, and, perhaps, most explicitly in L’Enfant (2005) [24], which received the prestigious Palme d’Or award at Cannes in 2005. This film, like their previous three major features (La Promesse, Rosetta, and Le Fils), as well as subsequent films since then (like Deux jours, une nuit), illustrates the redemptive force of responsibility, specifically, how the self is transformed in its response to the Other’s unrelenting interrogations and demands. L’Enfant tracks the movement from the arid, narcissistic, often violent, universe that the ego inhabits to the ethically meaningful world that is made possible by the Other’s provocation to respond. In other words, this film, like their other work, narrates the tensions that exist between the drama of being and the ethical intrigue of self and Other. It is important to note, however, that these dramas do not play themselves out in two distinct realities, one material, the other, immaterial. Rather, we experience ethical and spiritual transcendence in the very heart of embodied, material existence. In the first installment of Au Dos de nos images, Luc Dardenne singles out the following line from one of Levinas’s commentaries on rabbinical texts dealing with the messianic: “spiritual life is essentially a moral life and its home is the economic sphere” ([13], p. 62; trans. modified). To which the filmmaker immediately adds: “this view of Levinas is also that of our cinema” ([2], p. 71).

The film features a freewheeling homeless youth by the name of Bruno and his girlfriend Sonia. Bruno lives off Sonia’s welfare checks and his petty theft activity. We learn at the beginning of the film that Sonia, his girlfriend has just had their baby. While in the hospital, without telling her that he has done so, he sublets her apartment in order to pocket the extra money. When she finally tracks him down on the street to introduce him to his son, the hurried Bruno can barely spare a moment for his own prodigy. When Sonia lifts Jimmy, their son, so that Bruno might embrace him, his awkwardness barely conceals his disinterest. Indeed, he seems perversely relieved when a second or two later he notices that the would-be-victim he has been staking across the street is about to get away and he uses this as an opportunity to call his accomplice on his cell phone. That he reaches for his phone rather than the creature in Sonia’s extended arms establishes for the viewer the extent of his self-immersion. Bruno’s self-regard reaches its high-point when tired of having to wait in line for Sonia’s social assistance cheque he decides to take up the offer of one of his shady associates who claims to know someone who traffics in babies for the adoption black-market. Some time later that afternoon, Bruno, unbeknownst to Sonia, exchanges his own flesh and blood for a hefty wad of cash.

For someone who has not seen the film, the temptation at this point in my description of it might be to imagine Bruno as evil incarnate. Yet, the film discourages this view. The fact is that for much of the film, Bruno comes across as a likeable person. His playful demeanor and his easy-going attitude make him no different than any typical twenty-something male in our midst. As seen through the camera of the Dardenne brothers, Bruno is no monster. If he is capable of carrying out as objectionable a deed as selling his own son, we see that this has more to do with his all-too-human egoism and indifference than it does to some ostensible evil inclination operating within him. If we must speak of evil in this context then we must qualify it as Hannah Arendt did as utterly banal [25]. From his own selfish perspective, Bruno’s decisions appear to him not only beneficial but justified as well. Selling Jimmy for a few thousand Euros appears to him eminently reasonable. His son, after all, will be in better hands and he and Sonia desperately need the money. Thus when the alarmed Sonia asks him where Jimmy is, after returning to her with an empty baby stroller, Bruno responds matter-of-factly, “I sold him”. To which he then adds, as if to reassure her, “don’t worry we can always make another one”.

Bruno’s phenomenology resembles that of the natural ego that Levinas so vividly describes in Totality and Infinity [26]. His own immediate needs lead him in general to overlook the fact that the world is populated by distinct others. Bruno carries himself in such a way as to make the most of what he can get from others at the same time that he shuns their accusations or demands. The viewer cannot help but be struck by the fact that for virtually the entire film, Bruno avoids his son’s gaze. Similarly, throughout much of the film, even while in the midst of others, Bruno is shown to be engrossed with his cell-phone, as if to suggest that he prefers the distancing that such technologies afford him over the directness of human proximity. However, the power to stand back from the world—viewing the world as a spectacle for one’s own benefit—concomitantly reveals the self’s fettered state. Bruno’s universe is the utilitarian world of maximizing pleasure and avoiding pain. However, that way of comporting oneself, as Levinas shows, belongs to the impersonal drama of being. That is, the universe as it exists prior to the ethical orientation revealed by the Other, a universe comprised exclusively of things and images in flux and not creatures assuming the responsibility that proximity to one another demands. The flipside of the ego’s desire for anonymity and sovereignty is existential and spiritual imprisonment.

The theme of self-imprisonment and isolation is central for the Dardenne brothers as it is in the cinema of one of their most important influences, that is, the work of Robert Bresson. The older French director is worth noting for our purposes because he too sets for himself the goal of representing the hidden spiritual drama of the human being. Admittedly, Levinas and Bresson are working on different philosophical and religious registers. For Levinas, the inaccessibility of the divine acts as a foil that is meant to return us towards—what he calls the supreme “detour”10—the only legitimate access to the divine, namely, the inter-human drama. By contrast, for the Catholic Bresson, the distance from the divine serves to underscore man’s fallenness. For Bresson, if the Hidden God reveals Himself he does so primarily as the result of the unmerited grace that God shows for His creatures. Despite this difference—which ought not to be exaggerated, because frequently for Bresson the catalyst for spiritual conversion involves other human beings—there are shared concerns between Bresson and Levinas that are worth noting. These similarities, as we will see, can be gleaned from the work of the Dardenne brothers who are indebted to both figures.

Like Levinas, Bresson has an eye for the deep ambiguity that riddles the self. The ego for both of them simultaneously represents sovereignty and imprisonment. On the one hand, the fact that the ego emerges against the background of an infinitely vast universe is, to use Pascal’s language, a virtual miracle. The ego’s emergence is a major accomplishment in the face of the anonymous indeterminacy of being. On the other hand, the ego faces its own existence as a crushing burden from which it cannot free itself. Bresson, especially in his early and middle films, made use of the prison theme as a metaphor for the human condition. The Dardenne brothers similarly convey the insularity of Bruno by frequently showing him against a wall, in a solitary space, contained by a fence, looking through bars (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). A similar device was used in Rosetta to heighten the principal character’s isolation from the world (Figure 9).

Figure 6.

Isolation.

Figure 7.

Isolation.

Figure 8.

Isolation.

Figure 9.

Isolation.

What finally breaks the illusion of absolute sovereignty is the Other’s accusation. This provocation, and the possibility to respond ethically on the part of the self, offers the only genuine way to transcend the ego’s limited purview. In response to the Other’s provocation, the self undergoes a kind of self-hollowing or self-evisceration. The Other erodes the self’s psychic armor, so to speak, and, in the process, makes the self receptive to the demands of others. Only the Other’s face—or, proximity, to use Levinas’s later preferred term—has the power to address the ego, to call it out of its tendency to hide or dissolve itself into its surroundings. In the absence of the Other, that is, where immanence prevails, “everything is absorbed, sunken into, walled in being...” ([14], p. 182). The temptation of the ego—its desire to establish a shell-like insularity—is challenged by the Other’s proximity, which “forbids the reclusion and reentry into the shell of the self” ([14], p. 183).

The final scene of the L’Enfant—one that pays homage to the famous ending of Bresson’s Pickpocket—powerfully conveys the transcendence of the ego, and the idea that the ethical drama implicates three different agents or forces: self, Other, and the wholly Other. Appalled by his indiscretions, Bruno, after retrieving Jimmy at a much higher cost than the initial compensation he was offered for his son, turns himself into the police. In this last scene, we see Bruno in prison. Sonia, who until now has been estranged from Bruno, comes to visit him. True to their form, the brothers film this particular scene by foregrounding the proximity between Bruno and Sonia, but also between ourselves and the characters that we watch. In this ethically climatic moment, the filmmakers refuse us the safe distance that might soften the impact of a challenge to our narcissistic fancy for flight and escape. Instead, we are immersed into the material reality of the setting: the cold, cement enclosure of the prison visitor’s room, the ambient backdrop of nearby conversations, and various other noises like the shuffling of chairs and the reverberating footsteps on the hard ground. The camera carefully tracks the movements, always at close range, first of Bruno as he enters the room, expressionless (Figure 10). He sits across from Sonia. She asks him if he would like some coffee. She gets up to retrieve some from a nearby vending machine. The camera follows her, away from and then back to the table, where she sits again. They exchange glances. Ravaged by Sonia’s gaze, Bruno finally breaks down in a torrent of tears and sobs (Figure 11). His tears give way to hers. They reach for each other’s hands. The two faces draw together. Followed by forgiving caresses. We sense that something has come undone in that space. We are made to witness the ethical intrigue: the self that is eviscerated by the presence of the Other. His egoistic defences no longer intact, Bruno feels the full brunt of his shame for the terrible pain he has inflicted on his lover. We are not witnessing two egos in conflict or even collaborating with one another. At that very moment, Bruno encounters the Other, not another ego. As his Other, Sonia’s presence broaches Bruno’s bodily and psychic space. From a Levinasian perspective, something else has broken through in that space. However, all we can say of this “more” is that it “comes to mind”. What we are made of aware at such moments, for Levinas, is the third, an ethical surplus that neither the self nor Other could have authored and as such deserves the name, however provisional, of “God” or the “Infinite”. If it were not for this third, the universe would be as Hobbes described it a heartless homo homini lupus.

Figure 10.

Prison Scene in L’Enfant.

Figure 11.

Proximity in L’Enfant.

The ending of L’Enfant is reminiscent of the moral conversion undergone by some of Dostoevsky’s own male protagonists in the presence of female companions who they have otherwise mistreated. One thinks here of Liza in Notes from Underground and, of course, Sonia’s namesake in Crime and Punishment. Dostoevsky we know consciously conceived of these female characters as Mary Magdalene figures, and more importantly, as Mary Magdalene transfigured by the divine presence of Christ. These female characters resemble Christ in two important ways: like him, their essential goodness makes them targets of abuse, and also like him they demonstrate an extraordinary capacity for love and compassion even in the face of the bitter hatred that is personally directed at them (as a side-note, the original title for L’Enfant was supposed to be “The Force of Love”). This idea is equally central for Bresson who we know was profoundly influenced by Dostoevsky’s literature. At the end of Bresson’s Pickpocket (Figure 12), the male protagonist finally breaks down before the infinite patience of Jeanne who he had previously rebuffed and neglected. The final words of Pickpocket—“Oh Jeanne, to reach you, what a strange path I had to take”—reminds me of Levinas’s recourse in Otherwise than Being to an old Portuguese adage which he notes succinctly summarizes the ethical drama that implicates self, Other, and God. The proverb in question is “God writes straight with crooked lines” ([14], p. 147). The crooked lines here refer to the torturous and strained relations between self and Other in the human intrigue. The redemptive possibilities that open up as a result of these “crooked lines” gesture towards another more radical and invisible source of the human intrigue, namely, the divine.

Figure 12.

Proximity in Pickpocket.

Luc Dardenne recognizes that religion traces the contours that delineate the dramas as described by Levinas. In this regard, he has on more than one occasion acknowledged the legacy of the monotheistic traditions in shaping our spiritual interiority and ethical sensibility. In an interview with the Belgian review, Toudi, he remarks:

The biblical texts say what life should be according to God, life according to the Law, according to Love, according to Justice. If one sees something religious in our films, it’s no doubt because the experiences of our characters refer to this life according to God which even without God today continues for us the life that is the most humanly possible, not for all situations in life, but at least for some.[6]

Despite this admission, his own lack of faith leads him to speculate that the name of “God” is perhaps an echo of the mother’s unremitting love for her child11. In this way, he departs from both Bresson and Levinas, for whom the divine or the Infinite cannot be traced back to any particular person or thing in the world. That is Luc Dardenne’s wager.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that the “atheism” that is expressed in his understanding of his cinema challenges a dominant account of secularism that has until recently defined the modern age—but which we are only now seeing signs of a creative renewal. Today, philosophers like Jürgen Habermas [27] speak of “postsecularism”. The postsecular is not an abandonment of secularism. It represents an effort to free Enlightenment secularity from the false dichotomies that it sets up between belief and unbelief, faith and reason. Most significantly, the postsecular drops the pretence that secular reason is fully rational and transparent while religion ostensibly is driven by an irrational faith. Instead, the postsecular position concedes—as Luc Dardenne is prepared to do—that faith in something outside of oneself is a necessary precondition for subjectivity in general. This is a faith in the Other’s capacity to save me from the despair of impersonal existence, though not a faith in a personal deity: faith without faith. For these reasons, I think it best to conceive of the cinema of the Dardenne brothers as an exemplary expression of the postsecular. In her own exploration of their cinema, Sarah Cooper makes a similar claim: “This is post-secular filmmaking that is comfortable with the place of religion in an industrial world in which faith and unbelief sit side by side, and through which the remnants of Judeo-Christian commands and counsel live on in secular morals and conduct” [28]. The postsecular cinema of the Dardenne brothers bears witness to the absolute necessity for transcendence from the binding limitations of our egoism, as the sine qua non of human solidarity.

4. Conclusions

The postsecular cinema of the Dardenne brothers poses a unique challenge to both a traditional understanding of faith and the modern concept of secularism. Some of Luc Dardenne’s recent writing might be misinterpreted as a form of atheism. But this is no conventional atheism. He fully recognizes and respects that religion—and in particular, the monotheistic faiths—pays careful attention to a dynamic of faith that is so essential for the well being of the self and the solidarity of a community. Nevertheless, in his most recent work, he conceives of our current task as learning to live without recourse to a personal God. His reflections on these matters suggest that the brothers’ cinema is an appreciation of the critical role that belief in an infinitely loving Other plays in the emergence of human subjectivity. Without such a belief, the self would collapse back on itself. And, at the same, time, their cinema can be understood as an attempt to live that faith without necessarily invoking in name or in practice the institutions or discourses of traditional religion. Consequently, I think it might be best to describe the cinema of the Dardenne brothers as an expression of faith without faith.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ryerson University’s Faculty of Arts for a grant that made it possible for me to develop this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bert Cardullo. “Rosetta Stone: A Consideration of the Dardenne Brothers’ Rosetta.” Journal of Religion and Film. Available online: https://www.unomaha.edu/jrf/rosetta.htm (accessed on 3 February 2016).

- Luc Dardenne. Au dos de nos images (1991–2005). Paris: Seuil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Luc Dardenne, and Jean-Pierre Dardenne. Au dos de nos images II (2005–2014). Paris: Seuil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Luc Dardenne. Sur l’affaire humaine. Paris: Seuil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Luc Dardenne. “Peut-on penser l’inconsolable sans consolation? ” Interview by José Fontaine. Available online: http://www.larevuetoudi.org/fr/story/chapitre-x-peut-penser-linconsolable-sans-consolation-interview-de-luc-dardenne (accessed on 3 February 2016).

- Luc Dardenne. “Can the Inconsolable be Thought without Consolation? An Interview with Luc Dardenne.” In Accursed Films: Postsecular Cinema between the Tree of Life and Melancholia. Edited by John Caruana and Mark Cauchi. Albany: SUNY Press, forthcoming.

- Sarah Cooper. “Mortal Ethics: Reading Levinas with the Dardenne Brothers.” Film-Philosophy 11 (2007): 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- Philip Mosley. The Cinema of the Dardenne Brothers: Responsible Realism. London and New York: Wallflower Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- John Caruana. “The Drama of Being: Levinas and the History of Philosophy’.” Continental Philosophy Review 40 (2006): 251–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel Levinas. Time and the Other. Translated by Richard A. Cohen. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel Levinas. Existence and Existents. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel Levinas. God, Death, and Time. Translated by Bettina Bergo. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel Levinas. Difficult Freedom: Essays on Judaism. Translated by Seán Hand. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel Levinas. Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel Levinas. “Reality and its Shadow.” In The Levinas Reader. Edited by Séan Hand. Oxford and Cambridge: Blackwell, 1989, pp. 129–43. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Kearney. “Levinas and the Ethics of Imagining.” In Between Ethics and Aesthetics: Crossing the Boundaries. Edited by Dorota Glowacka and Stephen Boos. Albany: SUNY Press, 2002, pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel Levinas. Proper Names. Translated by Michael B. Smith. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried Kracauer. Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality. New York: Oxford University Press, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- André Bazin. What Is Cinema? Translated by Hugh Gray. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Libby Saxton. “Blinding Visions: Levinas, Ethics, Faciality.” In Film and Ethics: Foreclosed Encounters. Edited by Lisa Downing and Libby Saxton. New York and London: Routledge, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Luc Dardenne, and Jean-Pierre Dardenne. “Taking the Measure of Human Relationships: An Interview with the Dardenne Brothers.” In Committed Cinema. Edited by Bert Cardullo. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- La Promesse, Directed by Jean-Pierre Dardenne, and Luc Dardenne. Liège: Les Films du Fleuve, 1996, DVD.

- Le Fils, Directed by Jean-Pierre Dardenne, and Luc Dardenne. Liège: Les Films du Fleuve, 2002, DVD.

- L’Enfan, Directed by Jean-Pierre Dardenne, and Luc Dardenne. Liège: Les Films du Fleuve, 2005, DVD.

- Hannah Arendt. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. London: Faber & Faber, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel Levinas. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgen Habermas. An Awareness of What Is Missing: Faith and Reason in a Post-Secular Age. Malden: Polity Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sarah Cooper. “Put yourself in my place’: Two Days, One Night and the Journey Back to Life.” In Accursed Films: Postsecular Cinema Between the Tree of Life and Melancholia. Edited by John Caruana and Mark Cauchi. Albany: SUNY Press, forthcoming.

- 1I would like to thank Isobel Bowditch and Doug Cummings for reading an earlier version of this paper and for their insightful comments. Special thanks, as well, to Joe Kickasola for the invitation to contribute to this special issue, and for his encouraging support and feedback.

- 2See, for example: Bert Cardullo, 2002 [1].

- 3See [2,3,4]. All translations from these texts are mine.

- 4“Interview de Luc Dardenne” [5]. An English translation of this interview will appear in Accursed Films: Postsecular Cinema between the Tree of Life and Melancholia. Edited by John Caruana and Mark Cauchi [6].

- 5Despite the fact of frequently speaking with a common voice in many of their interviews, I cannot, of course, say with certainty that they share similar views on the matters discussed in my article. And, so, while I leave open the real possibility that Jean-Pierre may not always concur with his brother, Luc, on some of the details discussed here, I will, nevertheless, for the sake of my exposition, assume that their views coincide.

- 6See, in particular, Sarah Cooper [7] and Philip Mosley [8].

- 7I develop this notion of the dramatic dimension of Levinas’s philosophy in greater detail in “The Drama of Being: Levinas and the History of Philosophy.” [9].

- 8In the Jewish scriptures, the “here I am” [hineni] expresses the most vigilant form of readiness before the otherness of God, as attested mostly notably by Abraham and Moses. See, for e.g., Gen. 22:1 and 22:11.

- 9For an extended discussion of the Jewish apprehension with the image as it applies to Levinas’s thought and cinema, see Libby Saxton’s “Blinding Visions: Levinas, Ethics, Faciality.” [20].

- 10See, for example, Otherwise than Being ([14], p. 12).

- 11This is a theme he develops in Sur l’affaire humaine [4].

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).