1. Introduction

Therefore, I urge you, brothers and sisters, in view of God’s mercy, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship. Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will.

—Romans 12:1–3

Miracles happen, why play with if or if not? Why not have a movie that does not beat around the bush? Anyone can get healing at any time God wants and He does not jerk people around like secular writers of religious things who write about uncertain crap.

[…] the script is written by a struggling agnostic and represents the typical crap that wanders through their feeble non-committal minds.

—Netflix User Review. 2 stars

1

For all its facetiousness, the review of Jessica Hausner’s 2009 Lourdes quoted above gestures towards a serious provocation, which turns around the dualism of mind and body in relation to religion. Following a young MS sufferer’s visit to the eponymous pilgrimage site, somewhere around its midpoint, the film sees its protagonist, Christine, hitherto paralysed from the neck down, suddenly stand and walk. A miracle has seemingly occurred. But as the film draws to a close Christine stumbles, falls, and takes once more to her wheelchair, raising the devastating possibility that her healing has only been temporary.

A similar ambiguity characterises the final moments of Dietrich Brüggemann’s 2014

Stations of the Cross/Kreuzweg. Immediately after anorexic teen Maria, a young Christian compelled to give herself over to God as a human sacrifice, is declared dead by doctors, her chronically mute brother Johannes utters his first word. Has Maria’s martyrdom been justly rewarded? Or is this an ironic coincidence? The stylistic choices made by both Brüggemann and Hausner leave the spectator uncertain as to what exactly has occurred

2. Jonathan Romney, in his review of

Lourdes for the

Independent, puts the matter more eloquently, stating that, “you can’t easily pin down” these films, which are by turns “compassionate, ironic, slyly condemnatory. Put a Catholic and an atheist in the same screening, and they’ll see two different films” [

4].

For the anonymous Netflix user and Romney alike, the lack of formal and narrative closure seems to be symptomatic of a certain cinematic “agnosticism”. What enrages the former however is the manner in which this agnosticism forces the creation of meaning onto “the beholder”. Of course film history is familiar with the conceit of using narrative aperture, amongst other stylistic and aesthetic devices, in order to rupture illusionism and bring about an “active” spectator

3. It is my contention, however, that the effect of coupling religious subject matter with a very distinctive film style in

Lourdes and

Stations of the Cross goes beyond an intentionalist paradigm, as our reviewer would have it, or a politicised implication of the spectator in the film’s worldview, as film theory so often claims. Instead, in what follows I will examine how these films negotiate formally and thematically between faith and doubt, religion and secularism, cynicism and credence, arguing that their lack of decipherability is a deliberate strategy for illustrating—perhaps even simulating—the problem of belief

4.

In their fascination with religious themes and questions, these films stand in a tradition of works by filmmakers stretching from Carl Dreyer, Ingmar Bergman and Robert Bresson to Terrence Malick and Lars von Trier. However, while they occupy a similar place at the interstices of religion, secularism and art, their purview is rather different. These films do not proselytise. But nor, like the work of Luis Buñuel or Jean-Luc Godard, do they satirise, at least not straightforwardly

5. Eschewing adherence to either side of religious debate, they offer us experiences that resist easy classification. If we are to understand them as agnostic, it is my contention that—far from an individual position on the part of each filmmaker or a trite manner of forcing meaning-making onto the spectator—this is agnosticism is embedded in the film’s very frames. Through their aesthetic choices, these films are suggestive of a fundamental unknowability in relation to religious experience.

2. An Uncertain Style: Planimetric Staging in Lourdes

The events of

Lourdes turn around the visit of a group of pilgrims and their carers, members of the Order of Malta led by the devout Sister Cecile, to the holy site. Shot by Martin Gschlacht, with production design by Katharina Wöppermann, the film is cast in a heavily restricted colour palate consisting of muted colours with strong elements of fire engine red and cerulean blue: the red of the uniforms of the Order of Malta and the blue of the Virgin Mary [

7]. It opens with a high angle, wide shot of an empty hotel conference centre, which slowly fills from either side of the screen with characters, including Christine (Sylvie Testud), pushed in her wheelchair into the centre of the shot (

Figure 1). A certain theatricality in the film’s staging and shooting is thus announced from the outset, and Hausner explains that throughout the film, “the actors move almost as if they were in a ballet—they move in and out of a static frame that for its part stays detached and cool” [

7]. She adds that the camera, “is like God’s Eye—observing, never interfering” [

7].

Little action takes place over the film’s first half, which comprises a series of wry vignettes about the pilgrim experience and is shot mostly in medium close-up within Lourdes’s interiors, in keeping with Christine’s confinement to these spaces. Indeed throughout the film, the camera’s view of the world mirrors but does not replicate Christine’s view. A largely passive, observant character, Christine says little and gives little away (when asked for example whether she likes Cecile, Christine remains silent, offering up a habitual Giaconda smile)

6. Since she is in a wheelchair, her eye line often rests at the other characters’ waist height, tilting upwards when it takes in faces. The camera mimics this positioning, refusing point of view shots yet allowing us partial access to Christine’s observations. To give an example, at one juncture we hover at eye level with Christine as behind her. Her carer Maria and handsome helper Kuno brush hands (

Figure 2). We notice this tentative approach that she—and no one else—sees. Crucially however it is not framed for us through Christine’s perspective. We see like Christine but we do not see through her eyes: we share her observations but not her subjective responses to them.

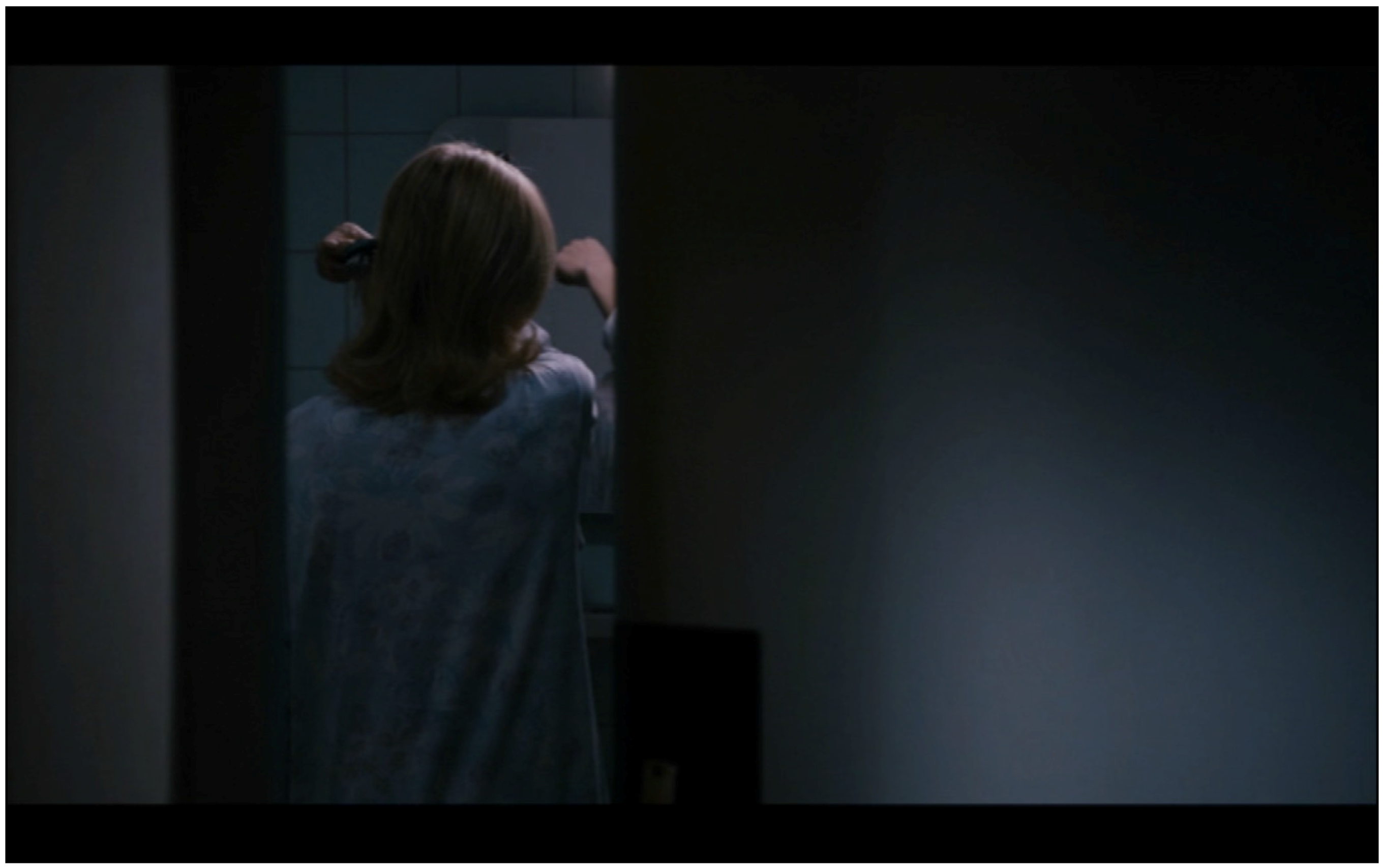

This epistemological disconnect becomes vitally important at the film’s turning point, when Christine rises from her bed and walks. A medium close up profile shot of Christine sees her lying in her darkened bedroom, her hands slowly unfurling before she sits and turns her back to camera. The lighting is dim to the point that Christine is almost a silhouette. Following a reverse shot of Christine’s roommate Frau Hartl watching Christine, the action then cuts to Christine standing and looking in the bathroom mirror, brushing her hair. What is so remarkable about this shot is that we see Christine through an open door that takes up only a fifth of a screen (the rest is blank walls), and can glimpse only the back of a head, a pair of shoulders, the tiniest suggestion of her reflection in the mirror (

Figure 3). Twice over we are denied the sight of Christine’s face: we cannot even begin to read her expression for signs of an emotional transformation. Christine is standing, this much we know, but it is hard to say what exactly has happened to bring this about. Later, at the film’s close, Christine will trip and fall during a dance with Kuno, and eventually return to her wheelchair. But although all the evidence is visible to us it is difficult to discern what is behind the events we see, not least due to the staging of the sequence.

In this closing scene, as throughout the majority of the film, Hausner and her production team draw heavily on two distinctive image schemas

7. The first of these makes use of what David Bordwell, following the art historian Heinrich Wölfflin, calls “recessive space” [

8]. Here, figures present diagonals that shoot from foreground to background by setting the foreground plane a distance from the camera, rendering characters’ expressions and relationships inscrutable and avoiding a clear focal point in the foreground. The second, Bordwell (again after Wölfflin) terms “planimetric”. In planimetric shots the background is resolutely perpendicular to the lens axis, and the figures stand fully frontal, in profile, or with their backs directly to us” ([

8], p. 167). Bordwell elaborates:

[In the planimetric shot], the camera stands perpendicular to a rear surface, usually a wall. The characters are strung across the frame like clothes on a line. Sometimes they’re facing us, so the image looks like people in a police lineup. Sometimes the figures are in profile, usually for the sake of conversation, but just as often they talk while facing front.

Sometimes the shots are taken from fairly close, at other times the characters are dwarfed by the surroundings. In either case, this sort of framing avoids lining them up along receding diagonals. When there is a vanishing point, it tends to be in the center. If the characters are set up in depth, they tend to occupy parallel rows.

The functions of the planimetric shot are various. In the films of Rainer Fassbinder and Kitano Takeshi, for example, it tends to evoke stasis and passivity, although for Kitano, as for Wes Anderson, it also gestures towards naivety and simplicity. Anderson also draws upon planimetric compositions to create a deadpan humour, as do Buster Keaton and Jacques Tati, two early practitioners of the shot. Nonetheless, if there is a prototypical use of the shot then for Bordwell it is in political modernist works such as Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise or Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielmann, films which draw upon the planimetric to suggest absurdity [

9]. Historically, both the recessive and the planimetric were used by filmmakers to dedramatize the action muting the flow of the narrative, hence their associations with neorealism, political modernism and counter-cinema. Far from diminishing our view of salient information, these shots place all the information on display but leave us clueless as to where this information is all heading. Hausner uses them in combination to rather different effect to previous filmmakers, however, as an aesthetic of agnosticism. To illustrate, let’s look at the closing few moments of

Lourdes.

The film’s final sequence takes place during a party celebrating the pilgrims’ last night in Lourdes (

Figure 4). In a straight-on shot, we are presented with Christine and Kuno dancing in the centre of the screen (

Figure 5). Behind them is a stage, framed by a proscenium arch of red balloons, on which a cabaret singer performs. Between the two, other couples dance. The focal pair revolve on the spot then turn to face each at right angles to the camera. Suddenly Christine drops out of the bottom of the frame. We cut to a recessive shot of some other party goers (

Figure 6), abruptly alert to the commotion, and back to Christine and Kuno, encircled by onlookers as he helps her up. The camera tracks them as they leave the dance floor and prop themselves against a wall in another example of recessive staging. It shifts perspective as the pair are joined by Frau Hartl, bringing Christine’s wheelchair. Kuno, Christine and Frau Hartl line up facing the camera in a planimetric composition (

Figure 7). Bruno departs, leaving Hartl and Christine dead centre, as if in a mugshot. There is then a cut to an extraordinary composition of four characters stacked back to back in an inverse V shape (these are the film’s Greek chorus and I shall return to them towards the end of the essay) (

Figure 8). Another planimetric shot shows us Maria and the singer bouncing on stage, singing, ironically—Al Bano and Romino Power’s Eurovision hit “Felicità/Happiness” (

Figure 9). A recessive shot lingers on Frau Hartl and Christine (

Figure 10). The latter eventually moves round into the front of the frame, lining herself up with her companion, and sits down in her wheelchair, transforming the recessive to the planimetric. The film closes on her face in profile, impassive and unreadable (

Figure 11).

Unlike the recessiveness of earlier directors such as Michelangelo Antonioni and Theo Angelopoulos, both of whom Bordwell has written about at some length [

10], Hausner’s recessiveness tends to be very shallow, lacking depth or distance, bringing it closer to a planimetric image. The diagonals that feature are stunted: they don’t take us into the frame—towards a far off vanishing point—but rather lead nowhere. Perspective is usually centered, as in the two shot of Fr. Hartl and Christine. The intercut planimetric shots that quite literally tackle their subject matter head-on are even more impenetrable to the spectator: the edits offering the promise of more information, but delivering more ambiguity, hence their ability to convey a sense of agnosticism. Their strict, stacked planes refuse us space to insinuate our gaze, or to plunge ourselves into a dynamic, diagonal, playing space. The images and characters square up to us, blocking entry into the cinematic world whose gates they guard. We can observe, but not interfere. The effect is heightened by the harsh halogen lighting. This lighting casts the interior world that Christine, for the most part, inhabits in a flat, shadowless pallor. When the action occasionally moves outside, individual portraits are replaced by frieze-like compositions or theatrical tableaux. In one particularly striking example the pilgrims line up under a series of statues at Lourdes Grotto, a stone wall splitting the screen horizontally in half so that the two groups appear as if reflections of one another (

Figure 12).

This stylisation—a kind of aesthetic minimalism that has led to comparisons with the photographer Jeff Wall [

4]—has superficial overlap with the Brechtian self-reflexivity of political modernism and its aim to create an “active” spectator [

5]. And indeed, as David Bordwell has pointed out, the planimetric and the recessive have often been explained in terms of an anti-Hollywood agenda and overarching resistance to bourgeois ideology ([

10], p. 266). But he also takes pains to underline that the two staging schemas can be bent to significantly different purposes, stating that, “As a pair of international norms, the perpendicular option and the oblique strategy answer to the transcultural and non-ideological purpose of directing or deflecting attention within the image, while also serving specific formal and expressive ends in particular films” [

10]. What, then, is the expressive end that these devices serve here? Succinctly put, it is to call attention to the impenetrability of the image, the inexplicableness of what we see. Throughout the film, the visual is foregrounded: through theatricality, through clear, overt presentation of events. But explanations are withheld. We might put this otherwise as a lack of priority within the image. That is, there is nothing—psychologically, formally, acoustically —to tell us which part of the image is the most important to be considering. This literal de-centring of the viewer gestures towards spectatorial humility, analogous to the Biblical idea: “who has known the mind of the Lord?” (Romans 11:34). The transcendental subject of apparatus theory is thus replaced by a spectator whose knowledge can only ever be partial, even when—indeed especially when—his or her vision is total.

Lourdes, then, is a film in which we see everything and yet we are unable to make easy sense of it. Hausner has herself has commented that her films are about “the mystery of human beings”, stating that “it is hard to know what goes on inside a person, one has to stay outside a person’s inner feelings. It’s impossible to understand someone completely or even half way. In that sense, everyone stays alone” [

7]. Just so, we see Christine as we see others in ordinary life. We face her. We look at her, and we see what happens to her. But that is all we can know, all there is for us to know. To paraphrase Susan Sontag, the temptation to search for a deeper meaning in

Lourdes should be resisted, because what matters is the pure, immediate, unfathomable surface of its images, and its rigorous refusal to offer us a beneath [

11]. Which is not to say there is no meaning to

Lourdes, but that there is no interpretative key: its meaning is there on the surface, in its liberating anti-symbolic quality.

3. Not Quite Spiritual Cinema: Stations of the Cross

Directed by Dietrich Brüggemann but scripted by his sister, Anna,

Stations of the Cross (henceforth

Stations) takes the principle of aesthetic minimalism underpinning

Lourdes and pares it back further still. The film is inspired by the Christian artistic tradition of The Stations of the Cross: a series of images—usually paintings but sometimes sculptures or tapestries—depicting Jesus’s journey to his crucifixion at Calvary. Starting with Christ’s sentencing and ending with his burial, there are usually fourteen stations, of which anywhere between seven and fourteen might be rendered. They hang in churches and cathedrals, serving as a reminder of the sacrifice that Christ made for the sake of humankind, intended to inspire contemplation, gratitude and remorse. The narrative follows teenage protagonist Maria (Lea van Acken), a member of the fictional Society of St. Paul

8, as she becomes increasingly extreme in her devotion to Jesus. After a chance remark by Father Weber causes Maria to consider the notion of self-sacrifice, she develops anorexia, believing that by giving herself to God she might win a miracle of healing for her mute younger brother. Sure enough, as Maria passes away, her young brother speaks his first word. In the film’s closing shot, her friend Christian is shown visiting her grave.

Mirroring its protagonist’s asceticism, the direction of

Stations is sparse to the point of abnegation. Cast in dingy browns, greys and greens, the film is divided into fourteen self-contained chapters each representing a different station and filmed in a continuous deep-focus long take. (The camera moves only three times throughout the film, notably during the last shot, when it pulls up and out into an overhead shot of the graveyard). Like

Lourdes, the film signals a relationship to art and artifice from its opening scene, which bears a remarkable similarity to Leonardo da Vinci’s painting The Last Supper (

Figure 13)

9. Indeed this film explicitly draws on a Christian art-historical tradition. Set outside in what appears to be a local park, the second chapter, “Jesus carries his cross”, calls to mind Raphael’s Madonna of the Meadows (1505) (

Figure 14), while in the eleventh, “Jesus is nailed to the cross” Maria resembles Bellini’s Imago Pietatis (

ca. 1457): eyes downcast, wrists crossed (

Figure 15). The framing and staging of each the fourteen long takes demand a comparison with classical works of painting, even where the reference points are less obvious. Brüggemann draws on the recessive far less frequently than Hausner, although chapter nine, “Jesus falls for the third time”, makes elegant use of church pews to create a layered structure of parallel receding lines, amongst which we must seek out Maria’s fervent face (

Figure 16). Likewise chapter three, “Jesus falls for the first time” deploys a series of stacked bookshelves to equally striking effect (

Figure 17). As if to hide the line these bookshelves inscribe, or prevent a psychological inference of a line (or vanishing point), the production designer seems to have pulled the back bookshelf more toward the middle of the frame, so the shelves (and back door of the room) look more like two-dimensional planes overlapping (as rectangles) rather than a receding series of volumes. Despite its actual depth, the recessive image feels very flat.

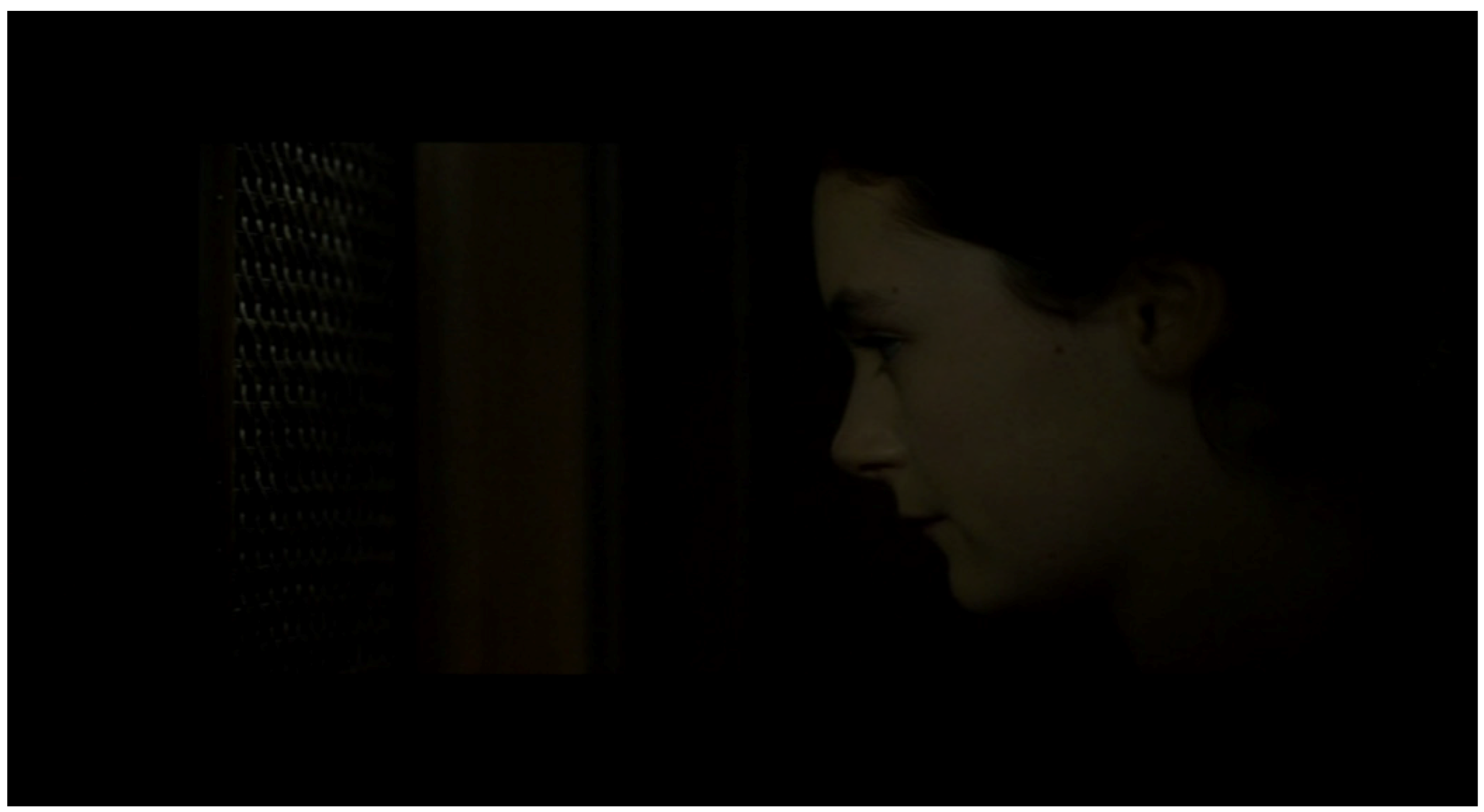

The film emphasises its construction, putting the tight framing to double work as it also provides a visual echo of the film’s theme of fundamentalism and oppression. Maria is literally boxed in. In chapter five, “Simon of Cirene helps Jesus to carry the cross”, Maria sits alone in a confessional, the small squares of the grill casting shadows on her face (

Figure 18). In chapter four, “Jesus meets his mother” she is framed in two shot with her mother through a car windscreen (

Figure 19). In three sequences, we see small groups positioned around a table, the perpendicular lines of the framing mirrored by the crucifixes that litter the background walls and the books that serve as an alternative to the pernicious pleasures of “a world of TV and Facebook and people who’ve sold their souls to be dead in the middle of life”. Like

Lourdes, too,

Stations features a scene in which characters pose for a group portrait, taking the planimetric aesthetic that underpins the two films to its logical extreme (

Figure 20 and

Figure 21).

The aesthetic minimalism that characterises

Stations of the Cross has been described by critics as “cold”, and “severe” [

12]. Incorporating chapter titles, long takes, minimal editing, a cast of largely non-professional actors, eschewing non-diegetic music and to a large extent plot (since we know where Maria is headed…), it has superficial similarities with what Paul Schrader has described as “transcendental” and Susan Sontag “spiritual” style, a style that while not explicitly religious is nonetheless couched in religiosity. In order to see how

Stations resists such religiosity, however, hewing instead to an agnostic aesthetic, it is important then to briefly delineate the defining characteristics of spiritual style.

Both writers refer to the work of Robert Bresson in describing the features of this strain of filmmaking, and both are heavily influenced by the French critic André Bazin. For Schrader, “transcendental style…strives towards the ineffable and invisible” through “...precise temporal means—camera angles, dialogue, editing—for predetermined transcendental ends” [

13]. Transcendental style seeks to “maximize the mystery of existence”, by “eliminating those elements that are primarily expressive of human experience, thereby robbing conventional interpretations of reality of their relevance and power” ([

13], pp. 10–11). It does so by reducing to status all those elements that help the viewer “understand” the event onscreen: “plot, acting, characterization, camerawork, music, dialogue, editing” ([

13], p. 11). Sontag couches her argument in terms of reflection and awareness of form. Bresson’s films, and those like them, present their form in an emphatic way, and as a result invite the use of reflection on the spectator’s part ([

14], p. 179). She states that:

Reflective art is art which, in effect, imposes a certain discipline on the audience—postponing easy gratification. Even boredom can be a permissible means of such easy discipline. Giving prominence to what is artifice in the work of art is another means. One thinks here of Brecht’s idea of theatre. Brecht advocated strategies of staging—like having a narrator, putting musicians on stage, interposing filmed scenes—and a technique of acting so that the audience could distance itself and not become uncritically “involved” in the plot and the fate of the characters. Bresson wishes distance, too. But his aim, I would imagine, is not to keep hot emotions cool so that intelligence can prevail. The emotional distance typical of Bresson’s films seems to exist for another reason altogether: because all identification with characters, deeply conceived, is an impertinence—an affront to the mystery that is human action and the human heart.

Aesthetically, Stations has certain commonalities with Bresson’s work. Since I am arguing here that the concern with mystery and its preservation—a definitive component of transcendental/spiritual style according to Schrader and Sontag—is essential to Stations (and in a different, but related, way to Lourdes) and since these films, like Bresson’s, preserve that mystery through the paring down of style, one might well ask why I do not consider these films to be doing the same thing as Bresson’s films. The answer involves several points.

Firstly, while Schrader is clear that what he calls the transcendental film style “is not determined by the film-makers’ personalities, culture, politics, economics or morality” ([

13], p. 3), and that transcendental art, “is not sectarian” ([

13], p. 7), he nonetheless emphasises Bresson’s own Catholicism as determinative of his aesthetic practices

10. So too does Sontag when she writes that Bresson is “committed to an explicit religious point of view” ([

14], p. 191). This contrasts with Hausner’s and Brüggemann’s statements to the effect that the films meditate on matters of faith without themselves being expressive of a religious worldview [

7,

12]. Brüggemann cites the global resurgence of radical practitioners of faith as inspiration for

Stations. “While in the late 20th century we were still able to believe that religion had more or less become irrelevant”, he states, “today we see the opposite everywhere: the spread of Evangelical Christians in America, the permanent media presence of militant Islam” [

15].

Stations imagines a local manifestation of this phenomenon: a portrait of fundamentalism and the damage that it can wreak on impressionable young minds, in the European context

11.

Second is the question of realism. Both at the level of style and narrative, Bresson’s films remain resolutely tied to the naturalistic. Characters live, suffer and die. His cinematography is rooted in a Bazinian realism that pays attention to the minutiae of the matter it captures through the objective quality of the cinematic lens. His films pretend to transparency: they offer a “window” onto the world in all its createdness, sloughing off the “spiritual dust and grime”, as Bazin puts it, with which our eyes have covered it, and presenting it “in all its virginal purity” to our attention and consequently, as Bazin would have it, to our love ([

16], p. 15). Thus Bresson’s works insist on the (film) world as an hierophanic expression of the divine and—related to this—on the inexorability of human destiny, as determined by divine providence. This predestination is expressed in the very titling of

Un condamné à mort s’est échappé ou Le vent souffle où il veut/A Man Escaped or: The Wind Bloweth Where It Listeth (1956), which announces the film’s conclusion before it has even begun [

17]. Both

Lourdes and

Stations, on the other hand, are characterised by a greater ambiguity, an ambiguity that is due in part to their aesthetic minimalism, but also, paradoxically, to the presence of miracles within these films, which introduce the supernatural into their purviews.

4. The Ineffable and the Unknown

At this juncture, I want to take a detour via Lars von Trier’s 1996 film Breaking the Waves, another work which turns upon the suffering female body and which concludes with what would appear to be a miracle, albeit of a different kind. Distraught after her husband Jan is paralysed in a mining accident, Bess, a simple young woman brought up in a strict Calvinist sect, becomes convinced that she can save him by having sex with strangers. After she is violently assaulted by two men on a ship at anchor in the harbour, Bess, like Maria, dies in hospital and shortly afterwards Jan is healed. She is to be given a sinner’s burial by the church elders but in the film’s closing sequence Jan and his friends are shown to have stolen her body and disposed of it at sea. The camera pans up to show heavenly bells ringing out in the sky.

Von Trier’s film has been widely written about in relation to questions of (largely Christian) religion and self-sacrifice

12, but two articles, by Jeffrey Pence and Stephen Heath, hold particular salience to my concerns here [

19,

20]. With specific reference to the film’s miracle, Heath suggests that there are two available readings. On the one hand

Breaking the Waves can be seen as naturalist, “involving no acceptance of any miracle but offering rather the painful and tragic depiction of a community and the harshness of its religion” ([

20], p. 94). On the other, the film can be seen as supernaturalist, “with Jan’s recovery having all the force of a miracle, allowing us very strongly to ascertain the power of love”. Heath continues: “Of course, these two versions go together, the recto and verso of a film that conjoins and slides between them in despair and euphoria, in trouble with their relation, their simultaneity” ([

20], p. 95). Ultimately, however, he argues that we have to come down on one side: belief in the miracle, or in the bells as metaphor: for freedom, for hope.

Jeffrey Pence takes issue with this either/or position. In “Cinema of the Sublime: Theorizing the Ineffable”, he argues that

Breaking the Waves is part of a body of films that “produce experiences, and call for responses, at the edge of the knowable”. In this much, his project would appear to be much like my own. Pence is concerned with “the limits of what we can know as a result of engaging with certain religiously inflected films”, and admonishes the reader that such an approach “begins with abandoning methodological certainty”. For Pence, insight into these films cannot be contained by a predetermined goal”, but he goes on to declare an interest in what he refers to as “spiritual films” (by which he understands films that address spiritual topics without relying on traditional sources of religious authority), thus aligning his critique with those of Schrader and Sontag

13.

For Pence, the spiritual, as the discourse for exploring experiences of what he terms “the ineffable”, “mediates between the otherwise opposed realms of transcendence and everydayness.”

It is a questioning of the possible meanings and implications of encounters otherwise beyond our customary cognitive and rhetorical categories of understanding; it speaks not strictly to the faculties of reason but to that admixture of thought and affect more characteristic of aesthetic experience.

Pence takes

Breaking the Waves as his indicative example of what such mediation might look and feel like. He refutes socio-historical readings that attempt to situate the film in contemporary European politics with recourse to the film’s “exaggerated conventions of realistic representation”, and “drive to exceed the particularities of its concrete setting” ([

19], p. 46). These excesses include director of photography Robby Müller’s frenetic, handheld camerawork, the film’s “extraordinarily palette of textures and colours”, wild sound, and Emily Watson’s emotive, melodramatic performance as Bess. For Pence, these features both ground the film in reality, bolstering its overall plausibility, and signal its spiritual aspirations. Most importantly of all, however, is the film’s ending:

…an ending that is comprehensible only in terms of the extraordinary, the transcendent, the sublime: a sudden, shocking encounter with an order or magnitude of being that nearly outstrips our abilities to perceive and process it […] By affirming Bess’s self-sacrifice through sensory evidence—not only Jan’s recovery but also the pealing bells of the over the ocean—the film’s ending redeems and embodies our affective investment in her spiritual desire.

([

19], p. 54, my emphasis)

Pence’s argument stumbles over something of a paradox here. For by claiming that

Breaking the Waves is typical of spiritual cinema in that it offers “representations of reality that are phenomenologically if not materially singular”, that its “indeterminacy may generate…affective involvement”, Pence allies himself —perhaps unwittingly—with a certain branch of affect theory spearheaded by Vivian Sobchack and Laura U. Marks

14. The problem for Pence is that far from calling for the spectator to abandon certainty, as Pence desires they should, such affect theorists lay distinct claims to knowledge through phenomenological subjectivism. That is, while Sobchack, Marks and company may reject objective, rational, “knowledge” of film, they nonetheless make a claim for the “somatic intelligibility” of the image and the “somatic intelligence” of the spectator’s body, to borrow Vivian Sobchack’s terms [

24].

For Sobchack, films that affect us bodily, as Pence claims

Breaking the Waves does, are meaningful

because of our bodies. Hence she is able to claim that when watching Jane Campion’s

The Piano, her fingers “

knew” what she was looking at

15. Von Trier’s film is undoubtedly one that produces a somatic experience. Bess herself is almost pure body: flailing, weeping, screaming, laughing, veering and wheeling. And Pence is right to point to the film’s melodramatic excesses as vital in our affective engagement with the film

16. But be that as it may, for Pence to claim that the

Breaking the Waves gestures towards the unknown because the language it uses is that of the body rather than the reason is at best somewhat naive, overlooking the body’s own claim to knowledge. Certainty is not the preserve of reason alone: as Sobchack so eloquently argues, the body can also offer certainty.

Thus while

Breaking the Waves may well replace rational argument with bodily affect, the result is the reinscription, rather than the abandonment, of certainty. Indeed Pence, in his own words, sees the “sensory evidence” of the film’s ending as incontrovertible ([

19], p. 61). And this conviction stems from the film’s melodramatic excesses. That is, the sheer emotional force of

Breaking the Waves—a film characterised by a frenzied, urgent desire to see, a desire thwarted until its very last moments—accounts for its ultimate persuasiveness. As Stephen Heath describes it, “the classic containment of the action of a film in a vision that the film steadily represents, is here bafflement […] distance and implication consequently lose all sense”. At least until, “the epilogue resolves the problems in that final shot, takes the miraculous distance of the absolute achieved, jumps from close-up, here and now naturalist particularity—the world of Bess and Dr. Richardson and oil-rigs and the church without bells—to the heavens—the re-establishment of the bells, recovering to this end a controlling third-person position” ([

20], pp. 102–3). It seems then that the “ineffable”, in Pence’s use of it, has more to do with that which cannot be articulated than that which cannot be known. The ending of

Breaking the Waves takes us beyond language, perhaps, but not beyond knowledge.

5. Conclusions: On Whose Authority, the Miracle?

What, though, of the ending of

Stations of the Cross? Where does that take us? As the camera cuts to reveal those bells at the close of

Breaking the Waves, we are left in no doubt as to what motivates this shot: the joyous peal of bells heard by the men on the rig below elicit a bodily sense of relief even before the impossible, otherworldly crane shot offers us a God’s eye view of the action (

Figure 22 and

Figure 23). We may buy into a supernatural reading of this end scene, or we may understand it as metaphor. Whichever side of the fence we come down on, it is clear that this final sequence offers a sincere celebration of Bess’s goodness. At the end of

Stations of the Cross the camera similarly pulls up and out to offers us a high angle on the scene unfolding (

Figure 24 and

Figure 25). As in

Breaking the Waves, this closing shot represents a stylistic break: we move from naturalism to supernaturalism in Von Trier’s film, from stasis to movement in Brüggemann’s. And both follow an apparent miracle following the heroine’s martyrdom: in the former, Jan walks; in the latter, Johannes speaks. Yet the appeal that Von Trier’s film makes to certainty—via bodily knowledge, via divine knowledge—is markedly lacking from Brüggemann’s film.

In fact extraordinary camera movement notwithstanding, the final shot of Stations is resolutely rooted in the natural. Opening with a mechanical digger heaping mud onto Maria’s open grave, it is sound-tracked by the dull crunching of operating machinery, and the penultimate sight it offer us is of Christian, Maria’s only friend, shuffling away from the grave with his hands in pockets, before the camera tilts to look upwards, towards the clouds. Since we have so far seen events through the fixed and rigid position of the art gallery patron, the possibility that we are witnessing a point of view shot floats before us, such that the movement might serve as a representation of Maria’s spirit rising upwards. But the rupture is a subtle one, the tone—bathetic, banal, mired in the grim and grimy—contiguous with what has gone before. This upwards gesture might be a final ironic shrug, the camera’s articulation of the sentiment “Is that all there is?”. Both readings are suggested. There is little within the image or its staging to help us decide between the two.

As we have seen, Pence and Heath disagree on the manner in which Breaking the Waves produces spectatorial knowledge. For Heath, the spectator understands the film’s conclusion rationally, for Pence, he or she understands it bodily. In their divergent ways, though, both these readings suggest that the film is ultimately knowable. We can say, with some confidence, what has happened. Time and again, Stations and Lourdes raise the question of whether it is ever possible pronounce judgement on the events that we witness within their narratives. Lourdes in particular repeatedly features diegetic audiences—at mass, at sermons, watching both singers and dancers at the disco—who comment with presumed authority on what they have seen. In one intriguing instance of mise-en-abyme, for example, we see the pilgrims watching a video of a man who has apparently been healed of lameness. Both we and they note that he sits throughout his testimony: thus even his authority over what has happened to his own body is troubled by their suspicions about his authenticity. Just so Christine’s miracle of healing would seem—at first at least—incontrovertible. Yet the Order’s first response is to appeal for the miracle to be recognised by the Vatican. In Stations, meanwhile, Maria’s mother insists upon her saintliness to the undertaker preparing her funeral, running through a checklist of her qualifications for official martyrdom before proclaiming that she will not rest “until her official beatification”.

Comparing personal faith with institutional religion, Mieke Bal has distinguished between “the desire for spirituality and the desire for authority” [

26], but

Lourdes and

Stations alike collapse this distinction, as so far as they frustrate any search for absolute truth or certainty. In fact, Hausner embeds a mocking commentary on the futility of the search for meaning in the film itself. As mentioned above, Lourdes features a Greek chorus of sorts, in the shape of Fraus Spor and Huber and their extended circle, a gang who constantly query whether Christine’s healing is a miracle and if so why her (as opposed to another pilgrim), falling back on circular logic and Church authority to make sense of events that are, perhaps, arbitrary. The mischievous humour with which they are treated serves as a reminder of how foolish such pursuits are. After Christine’s collapse, her fellow pilgrims speculate on her fate:

Person 1. A pity, I almost believed it.

Person 2. What do you mean? She tripped, that’s all.

Person 3. Just imagine if it doesn’t last? That would be so cruel. How could God do that?

Person 4. If it doesn’t last, then it wasn’t a real miracle. So He is not in charge.

Person 3. Who is then?

The open-ended discussion raises questions of interpretation as well as authorial intent: who controls events, and how do we understand them? Does the witness or creator have the final say? By poking fun at the interlocuteurs, though, Hausner suggests that such questions are not only empty but also absurd—and perhaps, after all, the two are not so different. The Brüggemanns meanwhile mock the notion of absolutes via the figure of Maria’s mother, who in response to one character’s consolation that, “Everyone has their own faith. Many roads lead to Rome”, admonishes, “No. There is only one way. People always mistake religion for some private matter. But religion is all about facts. Do you understand?”

If there is a lesson to be taken from these two films, perhaps it is precisely that religion is not all about facts, but rather about how we, as individuals, connect with the evidence before our eyes, evidence that can only take us so far. Perfectly poised at a precipice between faith and doubt, religion and secularism, cynicism and credence, both Stations and Lourdes make everything visible to us but refuse to comment upon it. In different but related ways their filmmakers present overlapping fields of possibility to the viewer, and ask him or her not to come to a firm conclusion on those possibilities, but to engage with them in a constructive, empathetic, and logically sensible way. In different but related manners, the films offer a challenge to integrate head and heart, perhaps. But for the spectator of Lourdes and Stations alike, all that we can be certain of is uncertainty itself.