Protocol of Taste and See: A Feasibility Study of a Church-Based, Healthy, Intuitive Eating Programme

Abstract

:1. Background: Obesity—What Has Religion Got to Do with It?

2. Aim

3. Objectives

- To determine how feasible it is to evaluate Taste and See within a UK church setting in preparation for developing a randomised controlled trial.

- To investigate change in physical, psychological and spiritual well-being in participants pre and post programme, and at six-month follow-up.

- To assess change in eating behaviour, nutritional intake and physical activity pre and post programme, and at six-month follow-up.

- To investigate participant acceptability of a Christian weight management programme to those who do not attend church or are not Christian.

4. Design

5. Participants

5.1. Inclusion Criteria

5.2. Exclusion Criteria

6. Recruitment Strategy

- To the church congregation through: posters, the church newsletter, the church website and announcements at Sunday services.

- Outside of the congregation through: word of mouth invitations to interested friends and acquaintances.

- An article about the study and an invitation to participate will be placed in the parish council magazine, which is distributed to all households in the area.

7. Sample Size

8. Ethical Approval

9. Information Session and Screening

10. Taste and See Programme Details

- Scientific content of evidence-based dietetic practice,

- Group activities to consider application of these dietetic principles in participants’ own lives,

- Biblical view on the issues raised,

- Opportunity, without obligation, to respond individually to spiritual content if participants wish to do so,

- Activity for the week to practice making health behavior changes,

- Daily Bible reading and prayer material for those who want to engage with this.

11. Ongoing Support and Follow-up

12. Group Facilitators

- The need for an ethical code of conduct regarding good clinical practice and spiritual diversity,

- The importance of good group facilitation and communication skills,

- Broad principals of intuitive eating and the need to support participants’ own behaviour change solutions rather than provide advice.

- Basic principles of a healthy diet and recommended physical activity levels as defined by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence.

- When to refer on to a professional counsellor or General Medical Practitioner,

- The importance of collecting data and evaluation procedures.

13. Measures

13.1. Demographics

13.2. Height, Weight, Percentage Body Fat and Blood Pressure

13.3. Depression, Anxiety and Mental Well-Being

13.4. Eating Behaviour

13.5. Spiritual Well-Being

13.6. Religious Well-Being

13.7. Religiosity

13.8. Physical Activity

13.9. Nutrient Intake

13.10. Participant Acceptability

13.11. Facilitator Feasibility

14. Data Analysis

15. Implementation of Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gema Frühbeck, and Volkan Yumuk. “Obesity: A Gateway Disease with a Rising Prevalence.” Obesity Facts 7 (2014): 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholas Finer. “Medical consequences of obesity.” Medicine 39 (2011): 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington: AICR, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Floriana S. Luppino, Leonore M. de Wit, Paul F. Bouvy, Theo Stijnen, Pim Cuijpers, Brenda WJH Penninx, and Frans G. Zitman. “Overweight, obesity, and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies.” Archives of General Psychiatry 67 (2010): 220–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Interventions on Diet and Physical Activity: What Works: Summary Report. Geneva: WHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harold Koenig, Dana King, and Verna B. Carson. Handbook of Religion and Health, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gary E. Fraser. “Diet as primordial prevention in Seventh-Day Adventists.” Preventive Medicine 29 (1999): S18–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajni Banthia, Judith Tedlie Moskowitz, Michael Acree, and Susan Folkman. “Socioeconomic differences in the effects of prayer on physical symptoms and quality of life.” Journal of Health Psychology 12 (2007): 249–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristopher J. Gauthier, Andrew N. Christopher, Mark I. Walter, Ronney Mourad, and Pam Marek. “Religiosity, religious doubt, and the need for cognition: Their interactive relationship with life satisfaction.” Journal of Happiness Studies 7 (2006): 139–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael King. “The Challenge of Research into Religion and Spirituality (Keynote 1).” Journal for the Study of Spirituality 4 (2014): 106–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven R. Hawks, Marylynn B. Goudy, and Julie A. Gast. “Emotional Eating and Spiritual Well-Being: A Possible Connection? ” American Journal of Health Education 34 (2003): 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborah Lycett. “The Association of Religious Affiliation and Body Mass Index (BMI): An Analysis from the Health Survey for England.” Journal of Religion and Health 54 (2014): 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kristie Lancaster, Lori Carter-Edwards, Stephanie Grilo, Chwan Li Shen, and Antoinette Schoenthaler. “Obesity interventions in African American faith-based organizations: A systematic review.” Obesity Reviews 15 (2014): 159–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeroen Barte, Nancy Ter Bogt, Rik Bogers, Pedro Teixeira, Bryan Blissmer, Trevor Mori, and Wanda Bemelmans. “Maintenance of weight loss after lifestyle interventions for overweight and obesity, a systematic review.” Obesity Reviews 11 (2010): 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traci Mann, A. Janet Tomiyama, Erika Westling, Ann-Marie Lew, Barbra Samuels, and Jason Chatman. “Medicare’s Search for Effective Obesity Treatments: Diets are Not the Answer.” American Psychologist 62 (2007): 220–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janet Polivy, Julie Coleman, and C. Peter Herman. “The effect of deprivation on food cravings and eating behavior in restrained and unrestrained eaters.” International Journal of Eating Disorders 38 (2005): 301–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfgang Stroebe, Guido M. van Koningsbruggen, Esther K. Papies, and Henk Aarts. “Why most Dieters Fail but some Succeed: A Goal Conflict Model of Eating Behavior.” Psychological Review 120 (2013): 110–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katrijn Houben, Anne Roefs, and Anita Jansen. “Guilty pleasures II: Restrained eaters’ implicit preferences for high, moderate and low-caloric food.” Eating Behaviors 13 (2012): 275–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurette Dubé, Jordan L. LeBel, and Ji Lu. “Affect asymmetry and comfort food consumption.” Physiology & Behavior 86 (2005): 559–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiera Buchanan, and Jeanie Sheffield. “Why do diets fail?: An exploration of dieters’ experiences using thematic analysis.” Journal of Health Psychology. Published electronically 16 December 2015. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maria Letizia Petroni, Nicola Villanova, Sebastiano Avagnina, Maria Antonia Fusco, Giuseppe Fatati, Angelo Compare, Giulio Marchesini, and QUOVADIS Study Group. “Psychological distress in morbid obesity in relation to weight history.” Obesity Surgery 17 (2007): 391–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linda Bacon, Judith S. Stern, Marta D. van Loan, and Nancy L. Keim. “Size acceptance and intuitive eating improve health for obese, female chronic dieters.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association 105 (2005): 929–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazanin Khasteganan, Deborah Lycett, Andy Turner, Amanda Farley, Nicola Lindson-Hawley, and Gill Furze. “Health, not weight loss, focused versus conventional weight loss programmes for cardiovascular risk factors: Protocol for a Cochrane Review.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7 (2014): CD011182. [Google Scholar]

- Jacinta Ashworth, and Ian Farthing. Churchgoing in the UK. A Research Report from Tearfund on Church Attendance in the UK. London: Tearfund, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Natti Ronel, and Galit Libman. “Eating Disorders and Recovery: Lessons from Overeaters Anonymous.” Clinical Social Work Journal 31 (2003): 155–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChurchCare. “Open and Sustainable.” 2012. Available online: http://www.churchcare.co.uk/churches/open-sustainable (accessed on 11 February 2016).

- Jan Karlsson, Lars-Olof Persson, Lars Sjöström, and Marriane Sullivan. “Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) in obese men and women. Results from the Swedish Obese Subjects.” International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorder 24 (2000): 1715–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan Michie, Michelle Richardson, Marie Johnston, Charles Abraham, Jill Francis, Wendy Hardeman, Martin P. Eccles, James Cane, and Caroline E. Wood. “The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 46 (2013): 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert L. Spitzer, Kurt Kroenke, Janet B. W. Williams, and Bernd Löwe. “A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7.” Archives of Internal Medicine 166 (2006): 1092–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurt Kroenke, and Robert L. Spitzer. “The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure.” Psychiatric Annals 32 (2002): 509–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth Tennant, Louise Hiller, Ruth Fishwick, Stephen Platt, Stephen Joseph, Scott Weich, Jane Parkinson, Jenny Secker, and Sarah Stewart-Brown. “The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation.” Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 5 (2007): 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy L. Tylka, and Ashley M. Kroon van Diest. “The Intuitive Eating Scale—2: Item Refinement and Psychometric Evaluation with College Women and Men.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 60 (2013): 137–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodger K. Bufford, Raymond F. Paloutzian, and Craig W. Ellison. “Norms for the spiritual well-being scale.” Journal of Psychology and Theology 19 (1991): 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jeff Levin, and Berton H. Kaplan. “The sorokin multidimensional inventory of love experience (SMILE): Development, validation, and religious determinants.” Review of Religious Research 51 (2010): 380–401. [Google Scholar]

- Harold G. Koenig, and Arndt Büssing. “The duke university religion index (DUREL): A five-item measure for use in epidemological studies.” Religions 1 (2010): 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal Krause. Religious Support. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research: A Report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Workshop Group. Kalamazoo: Fetzer Foundation, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- James F. Sallis, William L. Haskell, Peter D. Wood, Stephen P. Fortmann, Todd Rogers, Steven N. Blair, and Ralph S. Paffenbarger. “Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five City Project.” American Journal of Epidemiology 121 (1985): 91–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rod Dishman, and Mary Steinhardt. “Reliability and concurrent validity for a 7-d recall of physical activity in college students.” Medical Science Sports & Exercise 20 (1988): 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheila Bingham, Aedin Cassidy, Timothy Cole, Ailsa Welch, Shirley Runswick, Alison Black, David Thurnham, Chris Bates, Kay-Tee Khaw, Timothy Key, and et al. “Validation of weighed records and other methods of dietary assessment using the 24 h urine nitrogen technique and other biological markers.” British Journal of Nutrition 73 (1995): 531–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendy Wrieden, Heather Peace, Julie Armstrong, and Karen Barton. “A short review of dietary assessment methods used in National and Scottish Research Studies.” 2003. Available online: http://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/multimedia/pdfs/scotdietassessmethods.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Y. Claire Wang, Klim McPherson, Tim Marsh, Steven L. Gortmaker, and Martin Brown. “Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK.” The Lancet 378 (2011): 815–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | Key Points, Activities and (Key Behaviour Change Techniques) | Scientific Principle | Biblical Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1: Your Relationship with Food | |||

| To develop an awareness of self, of eating habits and of a God who cares about this | Everyone in the group has a similar problem (social support—general and emotional); this is something that you can involve God in, if you would like to (conserving mental resources). Complete food and mood diary (self-monitoring of behaviour) | The holistic aspects of eating The evidence for addressing the spiritual in weight management. | We are physical and spiritual beings. God loves us and wants to be involved in our lives |

| Session 2: What dietary rules do you follow? | |||

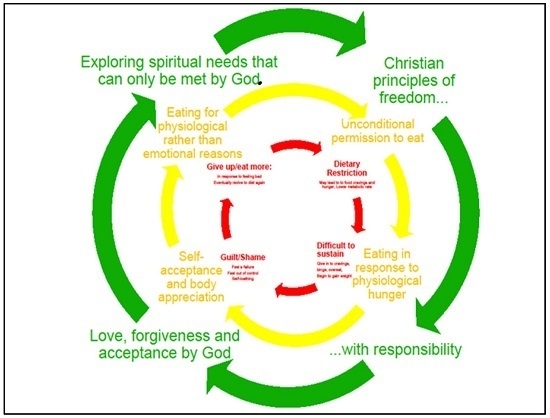

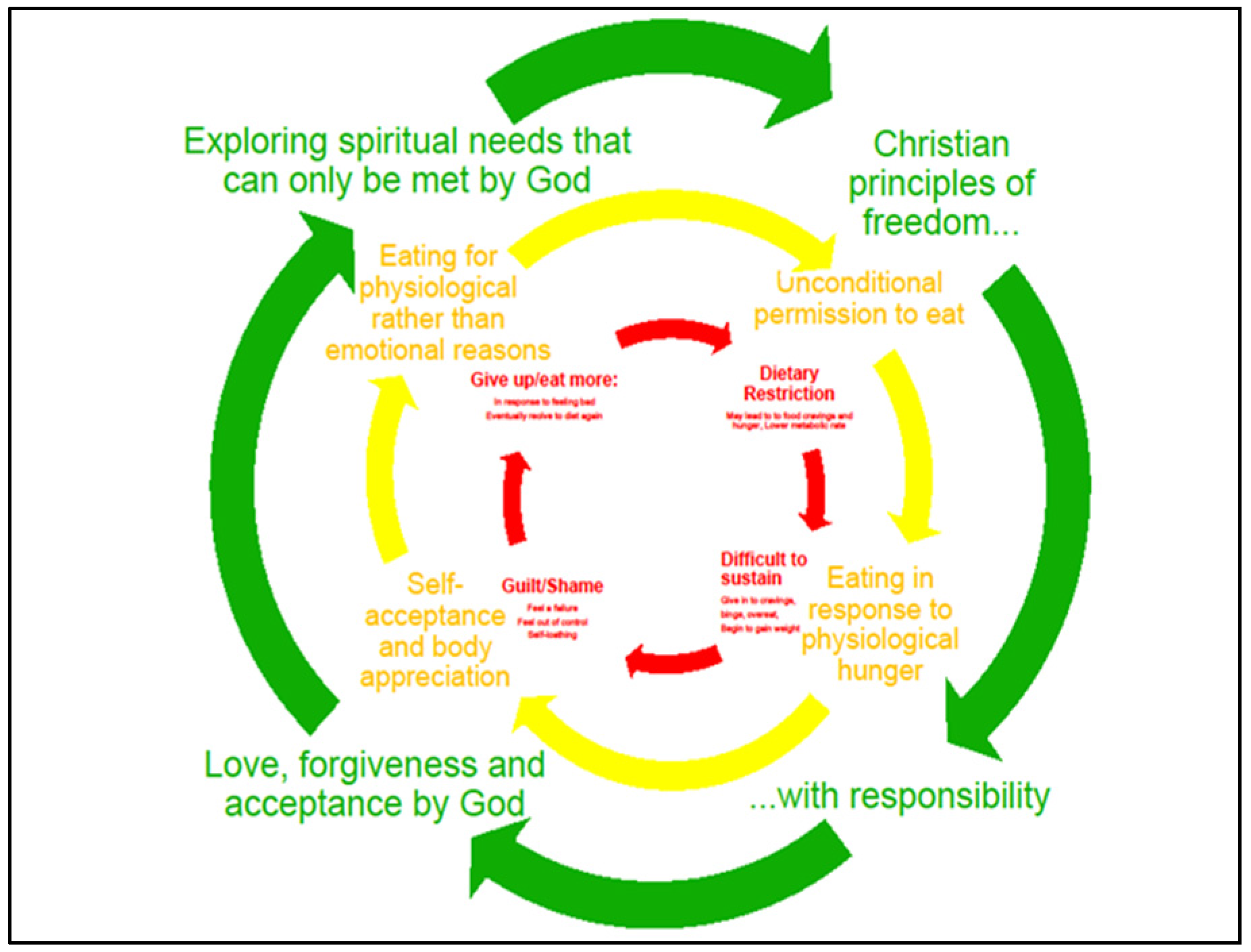

| To introduce intuitive eating versus dietary restriction | Dietary rules can be unhelpful, find out what yours are and consider whether they help or hinder you. What are the alternatives? (self-talk, reframing, cognitive dissonance, regulate negative emotions, behaviour substitution, habit reversal and formation, health consequences, emotional consequences, self-assessment of affective consequences, action planning). | The diet and weight regain cycle The evidence for finding what approach suits you The evidence for intuitive eating | Freedom with responsibility “Everything permissible but not everything is beneficial” |

| Session 3: Are you really hungry? | |||

| To identify hunger and fullness | Do you eat when you are full? Activities to practice listening to your body signals of hunger and fullness (anticipated regret, behavioural rehearsal, anticipation of future reward, avoidance—changing exposure to cues for the behaviour, self-monitoring of behaviour, action planning and implementation intentions). | Hormonal regulation of appetite What is a healthy diet? | Created by God A time for everything |

| Session 4: Enjoying food again | |||

| To feel free to enjoy food | Practice eating attentively, enjoy what you are eating, stop when you have finished. Is it appropriate to feel guilty? (behaviour rehearsal, anticipating reward, restructuring of the physical environment, goal setting, habit formation, regulate negative emotions) | Evidence for eating attentively, reducing distractions mindful eating exercise | The blessings of God, he loves to give us good gifts |

| Session 5: Why else do we eat? | |||

| To understand impulsive responses to feel happier, to feel less bored, to reduce stress | To identify times when we eat in response to emotion (self-monitoring of behaviour, action planning and implementation intentions, emotional consequence, self-assessment of affective consequences, self-talk, reframing, cognitive dissonance) | Dopamine pathway | The reality of life in an imperfect world/why things went wrong |

| Session 6: What can we do instead? | |||

| To identify ways to tackle boredom, stress and low mood | Plan alternative approaches, set clear goals of what to do differently this week in response to a specific trigger (distraction, avoidance—changing exposure to cues for the behaviour, goal setting, behaviour substitution habit reversal and formation action planning and implementation intentions, problem solving and coping planning, regulate negative emotions, self-talk, reframing) | Evidence based physical activity and relaxation suggestions | Spiritual coping Hope in difficult times |

| Session 7: Leaving the past behind | |||

| To identify past hurts or habits that still influence our relationship with food today, to find healing in forgiveness | Practice forgiveness (self-monitoring, self-assessment of affective consequences, self-talk, reframing, cognitive dissonance, regulate negative emotions, problem solving and coping planning, behaviour rehearsal, self-affirmation) | Evidence of the impact of adverse child events Evidence for forgiveness | “Forgive us as we forgive others” |

| Session 8: You are loved and you are lovely | |||

| To understand the truth of who you are | You are valued and loved for who you are (self-affirmation, verbal persuasion to boost self-efficacy, identity associated with changed behaviour, social support-emotional, self-talk, reframing, cognitive dissonance, regulate negative emotions) | Body congruence Tips to build self-esteem | God’s love and acceptance |

| Session 9: Moving forward | |||

| To consolidate new attitudes and behaviours, to identify specific aspects of healthy living to work on | It takes time and practice, but we have supernatural help (conserving mental resources, self-affirmation, verbal persuasion to boost self-efficacy, identity associated with changed behaviour, social support-emotional, self-talk, reframing, cognitive dissonance, regulate negative emotions, goal setting, behaviour substitution, habit formation, action planning and implementation intentions, problem solving and coping planning, distraction) | Goal setting Habit formation Tips and ideas for a healthy lifestyle | New creation, with God’s spirit at work within us |

| Session 10: Pressing on/The future | |||

| To equip participants to be able to continue the Taste and See principles without weekly support | It won’t always be easy, but we can live in forgiveness and freedom (self-affirmation, identity associated with changed behaviour, self-talk, reframing, cognitive dissonance, regulate negative emotions, goal setting, behaviour substitution, habit formation, action planning and implementation intentions, problem solving and coping planning, distraction, anticipation of future reward, avoidance—changing exposure to cues for the behaviour) | Identifying and planning for lapses Evidence for behaviour change maintenance | Pressing on and managing failure |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lycett, D.; Patel, R.; Coufopoulos, A.; Turner, A. Protocol of Taste and See: A Feasibility Study of a Church-Based, Healthy, Intuitive Eating Programme. Religions 2016, 7, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7040041

Lycett D, Patel R, Coufopoulos A, Turner A. Protocol of Taste and See: A Feasibility Study of a Church-Based, Healthy, Intuitive Eating Programme. Religions. 2016; 7(4):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7040041

Chicago/Turabian StyleLycett, Deborah, Riya Patel, Anne Coufopoulos, and Andy Turner. 2016. "Protocol of Taste and See: A Feasibility Study of a Church-Based, Healthy, Intuitive Eating Programme" Religions 7, no. 4: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7040041

APA StyleLycett, D., Patel, R., Coufopoulos, A., & Turner, A. (2016). Protocol of Taste and See: A Feasibility Study of a Church-Based, Healthy, Intuitive Eating Programme. Religions, 7(4), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7040041