Immeasurable Joy: Being One Meditation of a “Bodhisattva Vaibhāṣika”

Abstract

1. Ein buddhistisches Yogalehrbuch and an Elusive Yogaśāstra

2. Briefly on the Immeasurables

3. The Immeasurables in the Yogalehrbuch

4. The Theory of Practice

Opening the preface to joy, we first encounter an appeal to authority and an explanation of why she55 is to come after (anantaraṃ) compassion. The goal is to coordinate the two, with the suggestion that the former is the remedy for certain problems resulting from the latter. Although the precise nature of their relation is not altogether clear (to me at least), the sense of it all, it would seem, is that because compassion involves the disposition to remove the pain of another (duḥkhāpanaya), itself a remedy for malice (vihiṃsā), she can, by her focus, lead a yogin to themselves experience pain,56 jealousy (īrṣya) and a lack of delight (aprīti) for the painless and pleasurable state of this other, as well as dissatisfaction (arati) with their own.57 Joy is the remedy because her manner is enjoying (anumodanākāra, prāmodyākāra), being the disposition (āśaya) to enjoy others and so rejoice with them (cp. Guenther 1957, p. 164; Maithrimurthi 1999, pp. 134–37).Joy is theorised by the Blessed One after compassion. Now, as to their potential50 + + + + + + + + + + + +. For what reason is the theory of joy after compassion? Namely, it is (1) after the remedy for malice, for the purpose of visualising the remedy for jealousy51 and dissatisfaction;52 (2) after the remedy for delight in another’s pain, for the purpose of visualising the remedy for lack of delight in another’s pleasure; (3) after attention to the manner of aversion, for the purpose of manifesting attention that is consistent with the manner of enjoyment;53 or (4) after attention to the disposition to remove pain, for the purpose of manifesting attention to the disposition for welfare, pleasure and enjoying.54

Parallels for all elements of this passage are to be found in the *Vibhāṣā, on which basis it can be parsed into four discrete formulae, defining joy by her essence (svabhāva), basis (āśraya), object (ālaṃbana) and ground (bhūmi). Their identification is significant, representing (together with those from the prefaces of the other three immeasurables) the only attestations in Sanskrit of the kind of wording used by the *Vibhāṣā, which regularly applies these and indeed many more categories to several states of absorption, albeit in a different order to that encountered here and often with a detailed exegesis under each.68 Supposing the author relied directly on some version of the *Vibhāṣā, we can say that he was highly selective in doing so, only quoting the definitions of greatest relevance to his theory of practice. Such differences could just as well indicate that he drew upon another source, such as the yogaśāstra(s), which had already done the work of creating the digest we read here. One can therefore only guess as to why these four categories were finally chosen. Doubtless they were considered sufficient, and by definition fundamental, presumably reflecting a pragmatic concern with the utility of the text and the practice of the immeasurables it serves to example. Notwithstanding this apparent concision, there is still much contained in these pithy expressions and appreciating their significance will demand no small degree of consideration.atha kiṃsvabhāvā muditā tad ucyate •60 sauma(nasy)e(ndr)i[ya]svabhāvā61 sā tu sānuparivartā sasaṃprayogā parigṛ(hyamānā kāmāvacarā catuḥ)skandhasvabhāvā • r(ū)pāvacar(ā) paṃcaskandhasvabhāvā62 • āśraye kāmadhātvāśrayā63 • ālaṃbane kāmadhātvālaṃban(ā)64 bhūmi(taḥ kāmadhātau dh)y(ā)nadvaye ca65 tatra sau(manasyend)[r](i)y(a)sadbhā(vāt||)66 YL 153r2-467Now, what is the essence of joy? Namely, her essence is the faculty of gladness. But including her accompaniments and conjunctions, her sphere is sensuality and essence four aggregates (or) her sphere is materiality and essence five aggregates. With respect to the basis, her basis is the realm of sensuality. With respect to the object, her object is the realm of sensuality. As regards the ground, (she is) on the realm of sensuality and the (first) two absorptions because there the faculty of gladness has actual being.

4.1. The Essence of Joy

4.2. The Joyful Yogin

4.3. The Object of Joy

A sentient being possesses neither essence (svabhāva) nor substantial existence (dravayasat), being but a conventional concept (prajñaptisaṃjñā) given to what is in truth a collection and composite of the five aggregates.120 When practising the immeasurables, there is hence no sentient being to whom pleasure is given, from whom displeasure is removed, who is enjoyed, nor indeed about whom one is apathetic. So imagined as the object of meditation, a sentient being is said to be the result of attention to resolution (adhimuktimanasikāra), not attention to reality (tattvamanasikāra),121 and for this reason the experience is considered a delusion (viparyāsa).122As regards the object, one only perceives the realm of sensuality, collections (saṃghāṭa), composites (sāmagrī) and sentient beings (sattva); that is to say, one perceives sentient beings of the realm of sensuality with five aggregates or two aggregates as the object. If the thought of a sentient being is of the same ground (svabhūmika, ekabhūmika), one perceives five aggregates. If the thought of a sentient being is of another ground (anyabhūmika) or if they are without thought (acittakatva), one perceives two aggregates.119

4.4. A Practical Ontology of Joy

5. The Practice128

Her practice: (the yogin) is enraptured by the pleasure of a very strong friend, in the same manner for a moderate and a weak, a neutral, and in the same manner he is enraptured by the pleasure of a very strong enemy.129

Then, for he whose thought is bound fast to joy and is resolving towards sentient beings according to these kinds, a lotus pond appears in his heart, bedded with golden sand and filled with beryl-stalked golden lotuses covered with jewels. He sees sentient beings sat atop them, decorated with various ornaments, joyous. For he who has so seen the entire earth, rapture arises. As per the manner of enjoying, (he wishes), “May sentient beings be joyful!”130

Further, for he whose thought is immersed in the practice of joy, an ocean of sentient beings affected by manifold pleasures appears before him. + + + decorated like wheel-turning rulers are seen. And from his heart a golden banner arises. + + + + + + + + +, goes out from the top of his head, fills the entire world, releases a shower of various luxuries and finally a shower of jewels, with which the sentient beings do homage to the Buddha, the Dharma and the Saṃgha. In his heart, a joyful woman of golden light arises, the dominant form of joy. She encourages him, “Well done! It has begun beautifully!” In like manner, sentient beings in this world and the next are gratified with pleasure. Having seen as far as the Paranirmitavaśavartin gods, who are pleasured by pleasure, rapture arises. As per the manner of enjoying, (he wishes), “May sentient beings be joyful!”131

Afterwards, he sees sentient beings pleasured by a pleasure that is yet to come. Then, his body arises in the form of Brahma and variously arranged moon disks of golden light go out from all his apertures. He sees sentient beings sat atop them, with a like colour and encased, as if by bejewelled spired halls. Likewise, the endless world in the second absorption. In like manner, the realm is completely the colour blue.132 As per the manner of enjoying, (he wishes), “May sentient beings be joyful!”133

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Or simply Yogalehrbuch, as the text has come to be somewhat affectionately known in tribute to Dieter Schlingloff, who, in his 1964 edition and translation, named it thus in lieu of an extant title in the manuscript. |

| 2 | The main witness of the text is contained within a single birch bark manuscript written in the Sanskrit language and a north Turkestani Brāhmī script of the seventh century (Sander 1968, p. 46), which was discovered in a monastic cave complex at Qïzïl, near Kučā, located in today’s Xinjiang, China. The manuscript is highly fragmentary and has been estimated to represent a little under half of the text (Schlingloff [1964] 2006, pp. 10–12). |

| 3 | Several related paper fragments from distinct manuscripts, all written in the same script, were discovered at various sites in and around Kučā. Their contents are not entirely identical to the main witness and are for this reason regarded as idiosyncratic versions of a common text (Hartmann 2006, p. xiv). |

| 4 | That the manuscript is written on birch bark (the more usual medium for eastern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan) as opposed to paper (common to Central Asia), together with certain scribal errors that suggest it was copied from an exemplar written in the Gupta Brāhmī script of the fifth century, led Schlingloff ([1964] 2006, p. 13) to conclude that the text was modelled after an earlier version originating in South Asia. The content of the text moreover corresponds to other “treatises on yoga” that originated among the Sarvāstivādins of “Kashmir” (Ruegg 1967, p. 157), which shows it was the direct descendant of that region’s tradition. |

| 5 | Namely, (1) practice on impurity (aśubhaprayoga), (2) mindfulness of breathing (ānāpānasmṛti), (3) practice on the elements (dhātuprayoga), (4) observations of the aggregates (skandhaparīkṣā), (5) perceptual domains (āyatanaparīkṣā) and (6) dependent origination (pratītyasamutpādaparīkṣā), the four immeasurables (apramāṇa) of (7) friendliness (maitrī), (8) compassion (karuṇā), (9) joy (muditā), and (10) equanimity (upekṣā), and the recollections of the (11) Buddha (buddhānusmṛti), (12) Dharma (dharmānusmṛti), (13) Saṃgha (saṃghānusmṛti), (14) precepts (śīlānusmṛti), and (15) divinities (devatānusmṛti). |

| 6 | ato ʼnantaraṃ dhātuprayogo yogaśāstropadiṣṭo ʼnusartavyaḥ iha tu prayogamātraṃ darśayiṣyāmaḥ, YL 128R3. (“Immediately after this [i.e., the mindfulness of breathing], the practice on the elements as detailed in the yogaśāstra(s) should be followed. Here, however, we will present the practice alone.”) Citations of the Yogalehrbuch are mostly given according to Schlingloff’s edition, with a capitalised “V” denoting the Vorderseite (recto) and “R” the Rückseite (verso). I have, however, chosen to indicate missing akṣaras, both in transcriptions and translations, with “+” rather than with “..” as was Schlingloff’s convention. Any editions of my own employ a small “r” for recto and a small “v” for verso. |

| 7 | This yogaśāstra apparently inspired the very title Schlingloff gave to the Yogalehrbuch: “Statt der theoretischen Einleitung, die den anderen Kapiteln vorangestellt ist, wird hier auf das Yogalehrbuch verwiesen” (Schlingloff [1964] 2006, p. 86fn2). Eric Greene similarly suggests that yogaśāstra is a possible equivalent for chan jing 禪經 (“meditation scripture”), though admitting that its occurrence in Buddhist Sanskrit literature is here unique and so not altogether clear (Greene 2021, p. 46). |

| 8 | Included in this genre of Central Asian yoga manuals are “meditation scriptures” (chan jing 禪經) and “visualisation scriptures” (guan jing 觀經) extant in fifth century Chinese translations (Yamabe 1999b, p. 39ff) as well as others in Tocharian dating from around the same period (Huard 2022, pp. 275–78). Many of these works have similarly uncertain authorship, with some evidence of the Indic heritage they often claim as translations, though likely redacted or indeed entirely written as “apocrypha” in Central Asia (Yamabe 2006). Most show the influence of Sarvāstivāda thought, sometimes reflecting Dārṣṭāntika views (Yamabe 1999b, pp. 76–80), such as the Seated Meditation Samādhi Scripture 坐禪三昧經 (T 614), translated by Kumārajīva in 402 CE, or indeed Vaibhāṣika doctrines, such as the *Yogācārabhūmi (Damoduoluo chan jing) 達摩多羅禪經 (T 618) of Buddhasena and Dharmatrāta (fl. fifth century), translated by Buddhabhadra (d. 429), whose series of meditations most closely resembles that of the Yogalehrbuch (Inokuchi 1966; Abe 2023, p. 437), and the Secret Essentials of Meditation 禪祕要法經 (T 613), also translated by Kumārajīva, albeit in most cases with the more or less explicit involvement of Mahāyāna rhetoric (Demiéville 1954, p. 352ff; Donner 1977). All, however, are of a shared purpose, serving to illustrate the practice of yoga by drawing on a common cosmology and imagery from the Buddhist imaginaire to represent the experience of meditation, which is often depicted in the art of the region (Yamabe 1999a; 2002; 2004; Howard and Vignato 2014). |

| 9 | karuṇāprayoganirdeśaḥ kriyate, YL 147R2. (“The theory of the practice of compassion is given.”) |

| 10 | One cannot proceed without mentioning the Yogavidhi, a commentary on sutra quotations concerning yoga that constitutes the first half of the manuscript upon whose latter the Yogalehrbuch was itself inked (Schlingloff 1964). Notwithstanding the fact that this work does not bear the title yogaśāstra, it is in any case too fragmentary to be of much use here and will not be considered further. |

| 11 | An observation communicated in person at a Reading Retreat we and other members of our project (An English Translation of a Sanskrit Yoga Manual from Kučā, funded by The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation), Chen Ruixuan, Constanze Pabst von Ohain, and Zhao Wen, held together at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München in 2019. |

| 12 | Tradition holds that the *Vibhāṣā was composed as a commentary on the Jñānaprasthāna, the latest of six fundamental works of the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma, at a synod held in Kashmir during the second century. Today, there exist several distinct and somewhat later witnesses of the text, collectively designated here by *Vibhāṣā, following the title given by Vasubandhu (fl. fifth century) in his Abhidharmakośabhāṣya (see, e.g., Abhidh-k-bh 1, 20ab, Pradhan 1967). These include two partial Chinese translations, the Vibhāṣā 鞞婆沙論 (T 1547) from Śītapāṇi in 383 CE and the Abhidharmavibhāṣā 阿毘曇毘婆沙論 (T 1546) from Buddhavarman in 437 CE, one complete translation, the Abhidharmamahāvibhāṣā 阿毘達磨大毘婆沙論 (T 1545) from Xuanzang in 656–659 CE, and a few Sanskrit fragments written in a northern Turkestan Brāhmī script of the seventh century, one from Kučā (Enomoto 1996, p. 135), held in the Pelliot Collection at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris (No. bleu 333), and three from Turfan (Dietz 2004, p. 62), held in the Sanskrithandschriften aus den Turfanfunden (SHT) at the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Staatsbibliothek, Berlin (SHT VI 1362, SHT VII 1703, SHT VIII 1830, Bechert 1989, 1995, 2000). No version is quite the same, with each diverging on many consequential issues and so offering a glimpse into regional iterations of the text (Willemen et al. 1998, p. 138ff). All were once encyclopaedic in scope, providing exegesis on the metaphysics (abhidharma) of another five earlier Sarvāstivādin works, the Saṃgītiparyāya, Dharmaskandha, Prajñāptiśāstra, Vijñānakāya, and Prakaraṇapāda, together with the teachings of untold (and often unnamed) schools, scholiasts and yogins (Silk 2000, pp. 286–87). Their purpose is to delimit, once and for all, the very entities (dharma) out of which reality is ultimately made and to classify the total range of conditions that determine their phenomenal appearance in any given moment of perception. |

| 13 | The observation of impurity (bujing guan不淨觀, *aśubhaprayoga) is in the *Vibhāṣā named as the first method a yogin adopts to develop mindfulness (smṛti), as opposed to the mindfulness of breathing (ānāpanasmṛti) and the practice on the elements (dhātuprayoga), which are however presented as acceptable alternatives (T 1545, p. 205a24–28). It is therefore likely no coincidence that these three open the Yogalehrbuch, indicating that the author was reliant on a scheme of practice considered normative to the Vaibhāṣika tradition. As Abe Takako pointed out to me, there are other groupings of practices given in the *Vibhāṣā; for instance, the observations of impurity, friendliness and compassion, and dependent origination are named together, albeit not obviously in a series and rather as distint means to respectively suppress that famous trio of defilments, greed, hatred, and ignorance (T 1545, p. 9c14-16). |

| 14 | (anut)taraṃ dānaśīlavīryaprajñā, YL 164V6 (“the highest giving, morality, vigour and wisdom”). This enumeration is only found in the Abhidharmamahāvibhāṣā, wherein it is attributed to the Kashmiri teachers and contrasted with the better-known listing of six perfections, which is ascribed to certain “foreign teachers” who added patience (kṣānti) and absorption (dhyāna) (T 1545, p. 892a26–892b25). The Abhidharmadīpa, a fifth century composition, written in defense of the Vaibhāṣika position, also records this addition of a further two perfections, affirming, however: vinayadharavaibhāṣikās tu vinaye catasraḥ pāramitāḥ paṭhanti | Abhidh-d 195 (Jaini 1959). (“But the Vaibhāṣika Bearers of the legal code say there are four perfections in the legal code.”) To what legal code (vinaya) this refers is at once interesting and inexplicable, suggesting that the Vaibhāṣikas, rather than the Sarvāstivādins, the monastic institution (nikāya) with which they are presumably affiliated by (as is normally understood) ordination, had their own lineage, which to my knowledge is a notion otherwise unattested. |

| 15 | (tata) [ā](ś)[r](a)ye balavaiśāradyāveṇikasmṛtyupasthānamahākaruṇā[dh]i(patirū)[pā]ṇi dṛśyaṃte, YL 161R6–V1. (“Then in the body (of the yogin) are seen the dominant forms of the (ten) powers, (four) fortitudes, (three) special stations of mindfulness, and great compassion.”) Elsewhere, these 18 qualities are said to constitute the “body of qualities” (dharmaśarīra), which the yogin himself comes to embody (YL 165V4–R1). His becoming a Buddha has been labelled “‘mahāyānist”, with the notion, in particular, of great compassion (mahākaruṇā) considered as such (Ruegg 1967, p. 161; Hartmann 2013, p. 47). But the listing of the 18 special qualities (aveṇikadharma) of the Buddha first arises as an explanation of the dharmaśarīra in the *Vibhāṣā (see T 1545, p. 160c1–5, p. 624a13–15; T 1546, pp. 70c29–71a2, p. 104a1–3), which also becomes the object of Mahāyāna critique in the *Mahāprajñāpāramitopadeśa 大智度論 (T 1509) (Lamotte 1970, pp. 1625–27, 1697–99). In more than one Mahāyāna text, dharmaśārīra rather holds the sense of “dharma relic”, most likely denoting an object inscribed with the textual formula for dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda), which was thought to be the essence of the teaching, consubstantial with the Buddha, and so a surrogate for his corporal relics (Radich 2007, pp. 463, 706). Great compassion, moreover, though no doubt characteristic of Mahāyāna thought, is also defined in the *Vibhāṣā at length as a characteristic of a Buddha and more specifically in the section that details the four immeasurables (apramāṇa), where it is differentiated from compassion (karuṇā) on several grounds (T 1545, p. 428a5–c26; summarised in Lamotte 1970, pp. 1705–9). |

| 16 | YL 140R6–V2, 147R2–4, 153V2–4 (a new edition of which is presented below), 155V6–R1. |

| 17 | I refer to both the author of the text and the yogin whose practice it describes in the masculine gender, following the convention used by the Yogalehrbuch. |

| 18 | This text contains many critiques of the views in the *Vibhāṣā. It is known in two complete Chinese translations, the Abhidharmakośābhāṣya 阿毘達磨倶舍釋論 (T 1559) by Paramārtha in the sixth century and the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya 阿毗達磨俱舍論 (T 1558) by Xuanzang in the seventh century, in one partial palm leaf Sanskrit manuscript from Tibet (Pradhan 1967), and in several Sanskrit fragments from the region of Turfan (Dietz 2004, p. 62). |

| 19 | This text was composed as a Vaibhāṣika response to the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya and in particular to the Sautrāntika views presented by that work. It is known in one complete Chinese translation made by Xuanzang under the title Abhidharmanyāyānusāra 阿毘達磨順正理論 (T 1562) and in several Sanskrit fragments from Sengim, near Turfan (Dietz 2004, p. 62). |

| 20 | It is not clear who composed this work, although it was also written in defense of the Vaibhāṣika position, likewise against the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya (Jaini 2001). It is known to one partial palm leaf Sanskrit manuscript from Tibet, which includes its commentary, the Vibhāṣāprabhāvṛtti (Jaini 1959), and to three Sanskrit fragments from Turfan (Dietz 2004, p. 62). |

| 21 | aśubhānāpānasmṛti=dhātuprayogaḥ smṛtypasthānaparīkṣaḥ skandhaparīkṣaḥ āyatana-[pa]rīk(ṣa)ḥ pratītyasamu /// SHT I 623r5–7 (Waldschmidt 1965). (“Impurity, mindfulness of breathing and the practice on the elements, observation of the stages of mindfulness, observation of the aggregates, observation of the perceptual domains, (observation of) dependent origination.”) This fragment was previously ascribed to the Sarvāstivādins on the basis that this group was predominant in the region (Schlingloff [1964] 2006, pp. 26–27; Bretfeld 2003, p. 171) and has been used as evidence that the Yogalehrbuch was also circulating in Turfan (Yamabe 1999b, p. 64). It occurred to me that this text may represent something of a yogaśāstra, for it here lists the scheme of practice, which is a form of meta-analysis one would expect from a text concerned with the theory of yoga. |

| 22 | ime aṣṭadaśaprakārāveṇikabuddhadharmāḥ|| ekavidhaṃ tāvad=dharmaśarīraṃ (…) SHT I 623v7–r2. (“These are the eighteen kinds of special qualities of the Buddha, which are of one kind to the extent they are the body of qualities.”) |

| 23 | T 1858, p. 155c12–18. |

| 24 | A shallow dig did not expose much in the way of bibliographical details on this work. The present Taishō edition contains nine scrolls, but a concluding note to the text records the existence of an older version in six scrolls, as well as others, described in the Kaiyanlu 開元錄 (see T 2154, p. 541a10–11) as having five, seven, and ten (T 1525, p. 273c15–17). The latter may correspond to that noted in the Lidai sanbao ji 歷代三寶記 (T 2034, p. 86a16), which was transcribed in Luoyang by the monk Senglang 僧朗 (fl. sixth century). |

| 25 | These parallels are discussed below with the new edition I give for the theory of practice of immeasurable joy. One would have perhaps expected the same of the *Mahāprajñāpāramitopadeśa, though, as Étienne Lamotte observes: “Ici et contrairement à son habitude, le Traité s’ écarte de sa méthode ordinaire consistant à exposer d’abord les théories sarvāstvādin pour leur opposer ensuite le point de vue du Mahāyāna. C’est peut-être parce que les deux Véhicules sont d’accord sur un point essentiel: dans la méditation de bienveillance, etc., personne ne reçoit, personne n’est satisfait, et cependant un mérite naît dans la pensée du bienveillant par la force même de sa bienveillance (Kośa IV, p. 245). Les quatre immesurables sont des souhaits purement platoniques: il ne suffit pas de vouloir (adhimuc-) que les êtres soient heureux, exempts de souffrance ou joyeux pour que ce vœu soit réalisé.” (Lamotte 1970, p. 1240). |

| 26 | I would like to thank Chen Ruixuan for pointing out this appellation to me. To those familiar with the “paths” and “schools” of Buddhist history, the combination of these two epithets will no doubt be curious, for it is indeed quite unique, encountered only once as an ascription to a certain “Bodhisattva Vaibhāṣika Āryacandra”, the translator of the Tocharian Maitreyasamitināṭaka (A Play about a Meeting with Maitreya), who is named in chapter colophons to a 10th century Old Uyghur rendering of the text, the Maitrisimit nom bitig, attested in three manuscripts from the region of Turfan (MaitrSängim II, 14, v17–30; 20, v15–28). It should be noted that “Bodhisattva” is never encountered in colophons to the earlier eighth century Tocharian manuscripts, which rather name Āryacandra as Vaibhāṣika alone (A 258 b3 (THT 891), A 265 (THT 898) a1; A 297 (THT 930) a8; A 299 (THT 932) a7; A 302 (THT 935) b7 (Pinault 2022)). Reflecting on the significance of these epithets, Jens-Uwe Hartmann argues that Vaibhāṣika is not strictly partisan in intent but “steht hier vermutlich als Synonym für Sarvāstivāda”, and that Bodhisattva, too, is likely not an emblem of any specific Mahāyāna predilection, seeing as the Maitrisimit, and indeed the Yogalehrbuch, he suggests, both “einen Buddhismus repräsentiert, bei dem nicht nur Schulzugehörigkeiten keine Rolle (mehr) spielen, sondern bei dem auch die Grenze zwischen Hīnāyāna—wenn dieser Begriff provisorisch erlaubt ist—und Mahāyāna zu verschwimmen beginnt” (Hartmann 2013, pp. 43–47). Their combination, however, strikes me as quite revealing of Buddhist identity in this milieu of Central Asia, with “Bodhisattva” signalling that Āryacandra had made a vow for awakening, and was as such considered to be on the sublimest of paths, and “Vaibhāṣika” marking his adherence to that particular philosophical branch of the Sarvāstivāda school. He is more specifically said to be versed in the Nyāyānusāra (Hartmann 2013, pp. 43–44), a text written in staunch defence of the Vaibhāṣika position against its opponents, and this suggests there was a (neo-)Vaibhāṣika identity both in South Asia, where the Nyāyānusāra was composed, as well as in Central Asia from at least around the seventh century, as several manuscript fragments of the latter work were discovered in the region of Turfan (Dietz 2004, p. 62). One can therefore only assume that this “Bodhisattva Vaibhāṣika” was a salient social category, meaning that the pursuit of the Bodhisattva path through methods premised on Vaibhāṣika theory was normative and even estimably marked. Many yoga manuals that were likely current in the region represent something of a response to the *Vibhāṣā, both incorporating the ontology and the practice it advocates whilst seeking to go beyond it, often by the inclusion of Mahāyāna thought, and the Yogalehrbuch belongs to this general trend, forwarding the Bodhisattva ideal, albeit in terms that more or less conform to the *Vibhāṣā and without the inclusion of any Mahāyāna rhetoric. This latter connection requires greater elaboration than can be presented here. Concerning the presence of the Bodhisattva ideal in the Yogalehrbuch and other Central Asian yoga manuals, see Yamabe (2009). |

| 27 | Full reeditions of the four prefaces will be presented in a forthcoming volume to be published together with our project’s translation of the Yogalehrbuch. |

| 28 | Specifically in reference to a simile found in the Saṭṭipathānasutta, in which a monk is to divide up his body into the four elements (dhātu), earth (pathivī), water (āpo), fire (tejo) and wind (vāyo), just as a butcher does the hide of a cow (DN II, 294, Rhys Davids and Carpenter 1903). In the Yogalehrbuch, this is transformed into a vision of a blade emerging from the navel of the yogin to cut up his own body (āśraya) into the six elements (as per the Sarvāstivādin scheme) of earth (pṛthivī), water (ap), wind (vāyu), fire (tejas), space (ākāśa) and consciousness (vijñāna) (YL 160V1–2). |

| 29 | See Maithrimurthi (1999, pp. 13–34) for a lengthy discussion of the terms apramāṇa and brahmavihāra. |

| 30 | For instance, in the Mettāsahagatasutta: Samaṇo āvusogotamo sāvakānaṃ evaṃ dhammaṃ deseti || || etha tumhe bhikkhave pañcanīvaraṇe pahāya cetaso upakkilese paññāya dubbalīkaraṇe mettāsahagatena cetasā ekaṃ disaṃ pharitvā viharatha || tathā dutiyaṃ, tathā tatiyaṃ tathā catutthaṃ || iti uddhamadho tiriyaṃ sabbadhi sabbattatāya sabbāvantaṃ lokaṃ mettāsahagatena cetasā vipulena mahaggatena appamāṇena averena avyāpajjena pharitvā viharatha || || SN V, 115–116 (Feer 1898). (“Friends, the ascetic Gotama teaches the Dhamma to his disciples thus: ‘Come, bhikkhus, abandon the five hindrances, the corruptions of the mind that weaken wisdom, and dwell pervading one quarter with a mind imbued with lovingkindness, likewise the second quarter, the third quarter, and the fourth quarter. Thus above, below, across, and everywhere, and to all as to oneself, dwell pervading the entire world with a mind imbued with lovingkindness, vast, exalted, measureless, without hostility, without ill will.” (Bodhi 2000, pp. 1607–8)) Cf. T 99, p. 197b20–26. For variations on the formula in Sanskrit and Chinese sources, see Maithrimurthi (1999, pp. 35–39). |

| 31 | na nibbidāya na virāgāya na nirodhāya na upasamāya na abhiññāya na sambodhāya na nibbānāya saṃvattati, yāvad eva brahma lokupapattiyā, DN II, 251 (Rhys Davids and Carpenter 1903). |

| 32 | For a summary of the immeasurables in works of Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma, see Dhammajoti (2010); for both Sarvāstivādā and Yogācāra treatises, see Abe (2023, pp. 240ff). |

| 33 | In a rather lenghty explanation of why the immeasurables are otherwise called the abodes of Brahma (brahmavihāra), for which many reasons are given in order that the practices be placed firmly on the Buddhist path, the *Vibhāṣā highlights the immeasurables as the foremost among four means (constructing (1) a stupa for the Buddha’s relics or (2) a monastery in a previously unestablished location, (3) uniting a divided monastic community, and (4) practising the brahma abodes) to obtain the utmost merit of Brahma (brāhmapuṇya) (T 1545, pp. 425b09–426c27). |

| 34 | Bhikkhu Anālayo (2022, p. 214ff) argues that the immeasurables were originally conceived as boundless radiations but due to a literalist reading of a simile in which a monk is said to cultivate friendliness despite being carved up by a bandit, they later came to be directed towards other beings. This is encountered first in the Dharmaskandha, an early work of Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma, in which one takes one’s mother, father, brother, sister and other relations as the object; see Dsk 26r1–27v10 (Dietz 1984; Matsuda 1986); T 1537, pp. 485a26–488b13 (summarised in Dhammajoti 2010, pp. 175–76). |

| 35 | Their being “immeasurable” is due to (1) perceiving immeasurable sentient beings, (2) remedying immeasurable defilements, (3) generating immeasurable merit, and (4) generating immeasurable fruits (T 1545, pp. 420c13-29, 726c20-22). These four are also found in the Nyāyānusāra (T 1562, p. 768c26–29), as are the first, third, and fourth in the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya (T 1558, p. 150b20-22) (cf. Dhammajoti 2010, p. 166). Four reasons are also found in the Yogalehrbuch, which Schlingloff reconstructs as follows: ā(śrayāpramāṇata)yāpramāṇā ālaṃban(āp)r(amāṇatayā) + + + .(āpramāṇatayā puṇ)y(a)-prasavāpramāṇatayāpramāṇeti, YL 145V6–R1. (“They are “immeasurable” due to (1) the immeasurability of the body, (2) the immeasurability of the object, (3) the immeasurability of the + + +, and (4) the immeasurability of the generation of merit.”) Only two correspond to those named in other works, which of course leads one to question whether the reconstruction of the first is at all accurate. |

| 36 | |

| 37 | In the *Vibhāṣā, both the disposition (yi 意, āśaya) and manner (xingxiang 行相, ākāra) of each immeasurable are similarly defined, with friendliness being for the provision of pleasure (yule 與樂, sukhopasaṃhāra), compassion the removal of pain (baku 拔苦, duḥkhopanayana), joy enjoyment (xiwei 喜慰, prāmodya) or enjoying (qingwei 慶慰, anumodana), and equanimity apathy (shezhi 捨置, mādhyastha) (T 1545, pp. 421a18-19, 422a4-22). These take on typical expressions, as first encountered in the Dharmaskandha: sukhitā bata satvā iti evaṃ manasikurvvataḥ, Dsk 26r7 (“One attends thus: “Beings are pleasured!”); duḥkhitā bata satvā iti, Dsk 26v9 (“Beings are pained.”); modāntāṃ (sic) bata satvā iti, Dsk 27r5 (“May beings be enjoyed!”); ihaikatyasya satvā bhavanti, Dsk 27v4 (“Beings are of one kind.”). Much the same is found in later treatises (e.g., Abhidh-k-bh 8, 38abc; Abhidh-d 428) and indeed in the Yogalehrbuch, an example of which, in the case of joy, will be shown below. Schlingloff ([1964] 2006, p. 117) also notes some parallels in the Visuddhimagga of Buddhaghosa (fl. fifth century). |

| 38 | Precisely who belongs to this grouping alone is defined: 上品親者。謂自父母軌範親教, 或餘隨一可尊重處智慧多聞同梵行者。T 1545, p. 421c23–24. (“A strong friend is namely a father and mother, teacher, instructor or certain others of honourable standing who are wise and learned fellow brahmacārins.”) |

| 39 | T 1545, pp. 421c18–422a21 (summarised in Dhammajoti 2010, pp. 176–77). Taking friendliness (maitrī) as the paradigm, the *Vibhāṣā directs a yogin to first begin with a strong friend (such as a parent or teacher) and to formulate the disposition: “How may I cause this kind of sentient being to acquire pleasure?” (云何當令此有情類得如是樂。 T 1545, pp. 421c25–26). However, the rigidity of his mind prevents him from doing so easily, with bad intentions ever arising (even towards a great benefactor), and good intentions hard kept, “like throwing a mustard seed on the tip of a needle” (如以芥子投於錐鋒。 T 1545, pp. 421c29–422a1). Only when the seed sticks can he eventually take the remaining six kinds, in order, continuing with a middling and then a weak friend, a neutral, and finally a weak, middling, and strong enemy. The same method is applied to compassion and joy. For equanimity, the yogin is to follow a different course, beginning first with a neutral, followed by a weak friend, etc., and ending with a strong enemy. This is because, we are told, it is easiest to feel indifferent towards an individual to whom one has no personal relation, rather than a friend (whom one loves) or an enemy (whom one hates). This is done until the seven kinds are apprehended in the abstract “all sentient beings” (sarvasattva), “as if generally observing a forest” (如總觀林。 T 1545, p. 422a21). This scheme is not found in earlier works, but it does come to be reproduced in others, such as the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya, the Śrāvakabhūmi (Maithrimurthi 1999, pp. 207, 220), and the Nyāyānusāra (Dhammajoti 2010, pp. 177–78), as well as in those which comment on it, such as the *Maitreyaparipṛcchopadeśa (T 1525, p. 262b3-15). |

| 40 | It is asked, in the case of friendliness (maitrī): “What kinds of pleasure conferred on sentient beings does one perceive?” (緣何等樂與有情耶。 T 1545, pp. 423a6-7). Some suggest that one perceives the representations of pleasure (lexiang 樂相, *sukhanimitta), such as drink and food, vehicles, clothing, and so forth, and wishes that all sentient beings acquire the pleasure derived from such items (T 1545, p. 423a16-18). This appears to be a reference to the view of the Dharmaskandha, in which it is said one is to grasp certain signs of pleasure, such as warmth when cold, cold when hot, food when hungry, or the pleasure personally felt of the third absorption, and to resolve (adhi√muc) to give such feelings unto others (T 1537, pp. 485c07–86a13). The authors of the *Vibhāṣā would, however, appear to agree with another account: 大德說曰。先加行時緣曾所見諸有情樂。以憐愍心起勝解想。欲令一切欲界有情。平等皆得如是樂具。由此因緣皆受勝樂。此中意說。諸瑜伽師居近村城阿練若處。於日初分著衣持鉢。入近村城如法乞食。於所經處見諸有情純受勝樂。謂乘象馬輦輿等行。眾寶嚴身僮僕侍衛音樂讚詠。陳列香花受極快樂。如諸天子見諸有情唯受劇苦。謂無衣服頭髮蓬亂身體臭穢。手足皴裂執破瓦盂巡行乞匃。飢窮苦逼如諸餓鬼。見是事已速還住處。收衣洗足結跏趺坐。柔軟身心令其調適。離諸障蓋有所堪能。憶想先時所見苦樂。於有情類等起憐愍。欲令皆受所見勝樂。 T 1545, p. 423a26-b11. (“The Venerable One (likely one of two Dārṣṭāntikas, Dharmatrāta or Buddhadeva) teaches: “When one first practises, one takes the pleasures of sentient beings one has seen as the object, and out of pity gives rise to a resolute conception (*adhimuktisaṃjñā), wishing that all sentient beings in the sphere of sensuality equally attain such items of pleasure, for reason of which they all experience the highest pleasure.” Here, the intention is that a yogācāra residing in the araṇya (wilderness) near to a village or a city, in the morning dons his robe, takes up his alms-bowl, and enters the village or the city, as per the law on begging for food. Passing through these places, he sees sentient beings only experiencing the highest pleasures, such as travelling by carriage, elephant, horse, palanquin, etc., their bodies adorned with many jewels, with slaves and escorts, music and praise, displaying fragrances and flowers, and experiencing immense satisfaction. Just as princes see sentient beings only experiencing severe displeasures, without clothes, with dishevelled hair, smelly bodies, wrinkled hands and feet, clasping broken pots, going about begging, and afflicted by hunger, like a hungry ghost, he, having seen such things, quickly returns to his residence, removes his robe, washes his hands and feet, and sits in paryaṅka (cross-legged). With a pliant body and mind, he focuses. Free from hindrances, he becomes capable. Recalling and imagining the displeasures and pleasures he previously saw, he gives rise to pity towards the kinds of sentient beings, wishing to make them experience the pleasures that were seen.”) |

| 41 | T 1545, pp. 420c13–423b26 (summarised in Dhammajoti 2010, pp. 169–72); T 1546, p. 315b19–28; T 1547, p. 491b9–16. These passages will be treated further below. |

| 42 | Around 56 folios of the manuscript are extant (YL 115r1–171r1), of which the immeasurables, representing but four of fifteen practices, make up approximately 40% or 22 folios (139v5–163v6). |

| 43 | There is still much to be done in juxtaposing the Yogalehrbuch and the *Vibhāṣā, which may reveal further correspondences. But, it would appear that this affinity is not true of all practices. An important contribution was recently made by Abe (2024, pp. 14–15) in this regard, who has shown that the presentation of mindfulness of breathing (ānāpānasmṛti) in the Yogalehrbuch is minimally technical and tenuously related to the *Vibhāṣā. |

| 44 | Most of the 15 practices described in the text are said to be practised after (anantaraṃ, samantaraṃ) the last and therefore form a continuous series, with the expression here separating one practice from the next and so functioning as something akin to a chapter division (Schlingloff [1964] 2006, p. 116). However, the prefaces of the first and the second, the practice on impurity (aśubhaprayoga) and mindfulness of breathing (ānāpānasmṛti), and the final four recollections (anusmṛti) do not include this expression. In the case of the first, this could be due to the highly fragmentary state of the manuscript, but this practice, together with the second and the third of the text, the practice on the elements (dhātuprayoga), was regarded by the Vaibhāṣikas as the starting point for any practice of yoga, as noted above. Although the *Vibhāṣā affirms the canonical order of the immeasurables, the notion that they are immediate (wujian 無間, anantaraṃ) is a sticking point that comes to be ultimately negated on the technical basis that the four would co-arise and as such not be discretely identifiable states (T 1545, p. 422c21-26). |

| 45 | Several ailments are listed in the prefaces for most practices in the Yogalehrbuch, for which both Schlingloff ([1964] 2006, pp. 116–17) and Cousins (2022, pp. 138–39) provide useful tabulations. Many of those listed for the immeasurables have parallels in the *Vibhāṣā and other works of Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma; friendliness, for instance, is said to be a remedy (pratipakṣa) for malice (vyāpada), YL 147R1; 慈對治斷命瞋, T 1545, p. 420b16; compassion for striking and torture (daṇḍakaraṇa), YL 147R2; 悲對治捶打瞋, T 1545, p. 420b16-17; cf. karuṇā tāḍanapīḍanābhiprāyavartino dveṣasya pratipakṣo, Abhidh-d 427; and equanimity for craving (lobha) and sensual passion (kāmarāga), YL 155V3, cf. 捨以無貪善根為自性對治貪故。 T 1545, p. 420c5-6. Of the manners (ākāra) and dispositions (āśaya) still extant in the manuscript, friendliness is the disposition to provide welfare and pleasure (hitasukha[o]pa(saṃhārāśaya), YL 139r1-2), compassion attention to the disposition to remove pains (duḥkhitāpanayāśayamanasikāra, YL 153V1), and joy the manner of enjoyment (prāmodyākarā, YL 152V1, anumodanākāra, YL 153R5) and the disposition for the welfare, pleasure and enjoying (of others) (hitasukhānumodanāśaya, YL 153V2). |

| 46 | At the close of the mindfulness of breathing (ānāpānasmṛti), we read the following: tataḥ sarvaṃ jñeyaṃ yogācārāśraye ʼntardhīyat(e)| YL 127V6-v1 (“Then, all that is knowable dissappears into the body of the yogācāra.”). Or at the close of immeasurable compassion (karuṇā): ante ca sarvaṃ nābhyāṃ jñeyaṃ nirudhyate| YL 152R3. (“And at the end, all that is knowable is suppressed into the navel.”) |

| 47 | This title is mentioned only once as an epithet of the yogin in the practice of compassion (YL 150V6). |

| 48 | After a description of the cosmic tree under which the Bodhisattva, Siddhartha Gautama, first made his vow and thereafter attained awakening, we read: ta)t(o) ʼsya hṛdaye strī samutpadyate suvarṇavarṇā(vadātavastraprāvṛtā| sapaṭṭasuvarṇamā)lāv(a)b(a)ddh(ā) s(ai)n(aṃ) pr(o)tsāhay(ati|) tv(a)m (a)pi tāv(at) + + + + + + (sāv ātmānaṃ praṇamya bo)dhāya praṇidhānaṃ karoti, YL 151V6–R2. (“Then a woman arises in his heart, golden in colour, clad in white robes, and with a silken cloth and golden necklace bound to her. She exhorts him: “You (will) likewise + + + + +.” + + he bows himself before her and makes a vow for awakening.”) |

| 49 | About to follow the Buddha and his disciples through the gate to the city of nirvāṇa, watching them slowly disappear behind a bank of clouds (abhrakuṭa)—as nirvāṇa cannot be represented—a doorkeeper then warns the yogin that those who enter will never leave. The body of the yogin then transforms into the dharmaśarīra of the Buddha, resplendent with its 18 qualities, after which we read as follows: kṛtsnaṃ (satvasamudraṃ) + + + + + + + + + (dṛ)śyate| evam apāyasthānā bandhanabad(dh)ā (nā)nāduḥkhapīḍitāḥ + + + + + + + kathayanti ca paritrāyasva kāruṇikāsmāṃ nārhasi p(arinirvāṇanaga)r(aṃ gantuṃ| mahākar)u(ṇādhipa)tirūpaṃ cāsya yathoktaṃ hṛdaya u(tpadyate|) hastābhyāṃ ca ta(m anugṛhya kathayati| u)ts(ṛ)jya duḥkhitāṃ kva gaṃtum icchasīti| tasyopekṣā dūrībhavati| (ka)ruṇāvakramati| YL 162R4–6. (“An entire ocean of sentient beings + + + + + + + + + is seen. Just so, those in bad states, bound by bonds and crushed by various pains + + + + + + +. “Save us compassionate one!” they say, “You ought not enter the city of parinirvāṇa!” The dominant form of great compassion, as described, arises in his heart. Clutching him with both hands, she says: “Having abandoned the suffering, where do you wish to go?” His equanimity recedes, compassion takes over.”) |

| 50 | Schlingloff ([1964] 2006, p. 149) reconstructs tadsāma(rthya)ṃ, which he translates as “deren Funktionen”. However, I would here follow the Vaibhāṣika distinction made between the function (kāritra) of an entity (dharma), which denotes its actual causal efficacy and being (bhāva) in a given moment, past, future or present, from its potential (sāmarthya), which pertains to its timeless essence (svabhāva). Although this notion is first found in the *Vibhāṣā, it notably appears in the latest translation of Xuanzang alone, and only finds detailed exposition in the Nyāyānusāra of Saṃghabhadra, of whom it is understood by some to be the innovation (Dhammajoti 2015, pp. 147–49). As noted above, both texts were known to Sanskrit manuscripts in Central Asia in the seventh century, and it is thus entirely conceivable that the theoretical distinction in question was well-known to the author of the Yogalehrbuch. |

| 51 | In one Sarvāstivādin work, the *Abhidharmahṛdaya 阿毘曇心論經 (T 1551), attributed to *Dharmaśreṣṭhin 法勝 (fl. third century CE), we read: 喜眾生,如是想轉嫉對治喜根名喜。 T 1551, p. 857b4-5. (“Enjoying sentient beings: insofar as the remedy for the proliferation of jealousy is the faculty of gladness (saumanasya), it is called joy.”) |

| 52 | Cp. 喜若習若修。若多修習。能斷不樂。 T 1545, p. 819b21-22 (“If studied and practised repeatedly, joy is able to remove dissatisfaction (arati).”); 修行喜心下中上成就離不樂心, T 1525, p. 263b-2. (“Practising joy below, in the middle, and above, when perfected, removes dissatisfaction.”) |

| 53 | Cp. 喜謂慶慰作意相應喜根為性。 T 1545, p. 726c17-18. (“Joy is said to be conjoined (saṃprayukta) with attention to enjoyment (prāmodyamanasikāra) and to be gladness (saumanasya) in essence (svabhāva).”) Here and throughout, I use “to enjoy”, “enjoying” and “enjoyment” in their original causal sense in English, i.e., “to make joyous”, “to gladden”. |

| 54 | karuṇānaṃtaraṃ mudit(ā n)irdiṣṭā bhagavatā| atas tatsāma(rthya)ṃ + + + + + + + + + + + + kimarthaṃ ka(ruṇānaṃtaraṃ) m[ū]ditānirdeśas tad ucyate vihiṃsāpratipakṣānaṃtaram īrṣyāratipratipakṣāviṣkaraṇārthaṃ| paraduḥkh(a)prītipratipakṣānaṃtaraṃ vā parasukhāprī-(ti)pratipakṣāviṣkaraṇārtham| nirvidākāramanasikārānaṃtaraṃ vā prāmodyāk(ārā)nukūla-manasikāradyotanārtham| duḥkhitāpanāyanāśayamanasikārānaṃtaraṃ vā hitasukh(ā)nu-modanāśayamanasikāradyot(a)nārtham| YL 152R6–V2. |

| 55 | For reasons that will later become clear, I refer to all immeasurables in the feminine, reflecting both their grammatical gender as well as their appearing personified as women in the practice described in the Yogalehrbuch, as indeed we have already seen an example of above in the case of great compassion (mahākaruṇā). |

| 56 | As part of a discussion in the *Vibhāṣā concerning why a yogācāra is not harmed when practising the immeasurables, we read: 復次住悲等定雖不可害。而出定時身有微苦。 T 1545, p. 427a24–26. (“Further, even though one cannot be harmed while practising compassion, etc., when one emerges from practice, one’s body has a little pain.”). This is visualised in the Yogalehrbuch as follows: karuṇārtasya bhruvor madhye kṛṣṇataptaṃ piṭaka(m utpadyate|) YL 148V1. (“For he who is pained by compassion, an inflamed black blister appears between the eyebrows.”) |

| 57 | In the Nyāyānusāra, we read: 謂別有貪是惡心所,於有情類作是思惟:云何當令諸所有樂彼不能得,皆屬於我。喜能治彼,故是無貪,此與喜根必俱行故。 T 1562, p. 769a25–28. (“It is said that greed specifically is a bad mental state in which one thinks: “Why should I create pleasures for those who cannot obtain them when all belong to me?” Joy can remedy this because it is non-greed, and in this case must go togther with the faculty of gladness.”) |

| 58 | The *Vibhāṣā specifically aims to justify and coordinate the scriptural order of the immeasurables against certain yogācāra who would seek to practise otherwise. It does so by citing other yogācāra who suggest that the sequence derives from the character (xiang 相, lakṣaṇa) of each immeasurable, such that one must first wish to confer pleasure on other sentient beings out of friendliness and then remove their pain out of compassion before one can feel joy in their enjoyment and finally abandon all affection for them out of equanimity (T 1545, p. 422b15-28). |

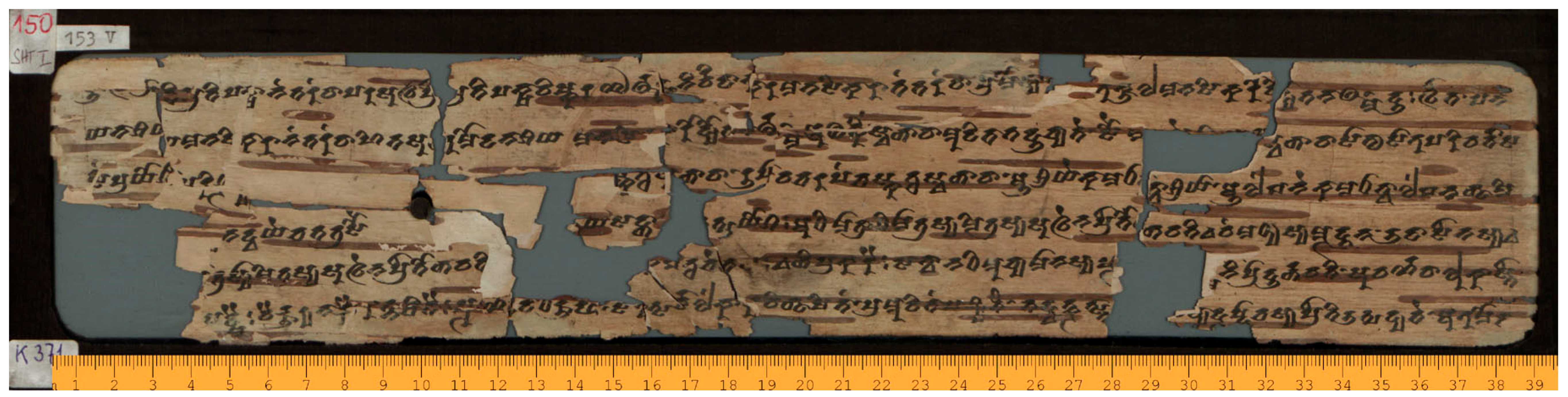

| 59 | Ink on birch bark, written in the Sanskrit language and north Turkestani Brāhmī script, type a (seventh century), from Qïzïl, Xinjiang, China. Currently held in the Sanskrit–Handschriften aus den Turfanfunden (SHT) collection at the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Staatsbibliothek, Berlin (SHT 150/2.39). Image from the International Dunhuang Programme (www.idp.bl.uk). A facsimile can also be found at (Schlingloff 1966, p. 31). |

| 60 | Such punctuation marks are to be understood as something akin to a comma. Schlingloff employed the daṇḍa (|) to represent them throughout his edition, but this symbol is used elsewhere with a stress more akin to that of a full stop. |

| 61 | Cf. sauma(na)[s](y)e(t)i [sa] svabhāvā (“Sie ist ihrem Wesen nach aus Frohsinn bestehend”) (Schlingloff [1964] 2006, p. 150). The new reconstruction is the more favourable. First of all, what Schlingloff read as [sa], of which only the upper part of the akṣara is preserved, is perhaps better read as [ya], which is in any case a reading confirmed by the parallels identified in the three Chinese translations of the *Vibhāṣā: 喜以喜根為自性。T 1545, p. 420b20 (“Joy takes the faculty of gladness as its essence”); 喜是喜根, T 1546, p. 315a29; 喜根性 T 1547, p. 491b1. The same formula is cited in the *Maitreyaparipṛcchopadeśa: 喜心體者,謂喜根是 T 1525, p. 263a7. |

| 62 | 若兼取相應隨轉, 則欲界者四蘊為自性, 色界者五蘊為自性。 T 1545, p. 420b20-21. (“Including the conjunctions and accompaniments, when of the realm of sensuality, their essence is four aggregates and when of the realm of materiality their essence is five aggregates.”) The parallel in the Abhidharmavibhāṣā is the same in meaning but closer in wording to the Yogalehrbuch, placing accompaniments (huizhuan 迴轉, anuparivarta) before conjunctions (xiangying 相應, saṃprayoga): 取其迴轉相應共有法, 體是四陰五陰,欲界是四陰、色界是五陰。 T 1546, p. 315a29-b2. The Vibhāṣā and the *Maitreyaparipṛcchopadeśa retain a slightly different reading: 取彼共有法相應法,欲界色界五陰性。 T 1547, p. 491b1-2 (“Including the co-arising (anuparivarta) entities and conjoined (saṃprayoga) entities, the essence is five aggregates in the realm of sensuality and the realm of materiality”); 此四無量共心展轉五陰為體。 T 1525, p. 263a13–1. The reason for this difference is treated in further detail below. It should be noted that this expression in the *Vibhāṣā is to be construed together with the preceding definition of the essence. |

| 63 | The two earlier translations of the *Vibhāṣā correspond precisely to what we read here: 所依者依欲界。 T 1546, p. 315c13-14; 依者,依欲界。 T 1547, p. 491b17. The latest translation, however, reads: 此四無量所依者。唯依欲界身而得現起。 T 1545, p. 421a17-18. (“The basis of the four immeasurables: (they are) are to be produced (utpatsyante) based solely on a body (āśraya) of the realm of sensuality.”) This differs slightly from other versions which do not supply the term for body (shen 身, āśraya, kāya), regarding which more will be said below. In the *Maitreyaparipṛcchopadeśa, the same is phrased in question and answer fashion: 依止何處者?依止欲界 T 1525, p. 263a24-25. (“In what location are (the immeasurables) based? (They are) based in the realm of sensuality.”) |

| 64 | 所緣者。唯緣欲界。T 1545, p. 421a20 (“As regards the object, (one) only apprehends the realm of sensuality”); 緣者,盡緣欲界。 T 1546, p. 315c15; 緣者【。。。】緣欲界者, T 1547, p. 491b18-22; 觀何法者?謂觀欲界, T 1525, p. 263b8. |

| 65 | 地者。。。喜無量在三地。謂欲界初二靜慮, T 1545, p. 421a1–4; 地者。。。喜在三地,欲界、初禪、二禪。 T 1546, p. 315c3-5. (“As regards the grounds… immeasurable joy is on three grounds; namely, the realm of sensuality and the first and second absorptions.”) The Vibhāṣā names seven grounds, which are in the other two later versions given only in relation to friendliness, compassion and equanimity: 地者七地,欲界依未來、禪中間、根本四禪。 T 1547, p. 491b16-17. (“As regards the grounds, there are seven grounds: the realm of sensuality, not-yet-arrived, intermediate absorption and the fundamental four absorptions.”) More on this difference will be said below. |

| 66 | Cf. tatra sau(manasyaṃ [dv](a)y(a)sadbhā[v]aṃ|| (“Hierbei [bedingt] (der Frohsinn) das Vorhandensein der Zweizahl”). As Schlingloff ([1964] 2006, p. 150fn6) notes, the reconstruction here is uncertain. One passage from the two latest versions of the *Vibhāṣā, though constituting an alternative explanation for the object (ālaṃbaṇa) of joy, would appear to provide a solution: 喜無量緣欲界及初二靜慮。所以者何。喜無量喜慰行相轉, 唯三地中有喜受故。 T 1545, p. 421b6-7 (“Immeasurable joy perceives the realm of sensuality as well as the first and second absorptions. What is the reason? Immeasurable joy operates with enjoying (anumodana) as her manner (ākāra) because it is only on three grounds that there exists (sadbhāva) the feeling of rapture (prīti)”); 喜緣欲界初禪第二禪。所以者何?喜行歡喜行,欲界初禪第二禪有喜根故。 T 1546, p. 315c25-27 (“Joy apprehends the sphere of sensuality, the first absorption and the second absorption. What is the reason? Joy operates with the manner of enjoying because it is only in the sphere of sensuality, the first absorption and the second absorption that the faculty of gladness (saumanasyendriya) exists”). See also: kāmadhātau prathame dvitīye ca dhyāne sā caitasikī śātā vedanā saumanasyendriyam, Abhidh-k-bh 2.7. (“In the sphere of sensuality and the first and second absorption, the mental factor and feeling of joy is the faculty of gladness.”) |

| 67 | It is incumbent upon me here to thank both Chen Ruixuan and Habata Hiromi for their comments and corrections on the edition presented here. Any errors that remain are my own. |

| 68 | To give but an excerpt of all the categories under which the four immeasurables are defined in the *Vibhāṣā, we have, in order, their essence (svabhāva), characteristic (lakṣaṇa), and why they are called immeasurable (apramāṇa), their realm (dhātu), ground (bhūmi), basis (āśraya), manner (ākāra), and object (ālaṃbana), their relation to the stations of mindfulness (smṛtyupasthāna), kinds of knowledge (jñāna), and grounds of concentration (samāhitabhūmi), the three times (adhvan), their conjunction with the faculties (indriyasaṃprayoga), etc. (T 1545, pp. 420b08–421c8; T 1546, pp. 315a17–316a22; T 1547, p. 491a26–c20). |

| 69 | T 1545, p. 308a20–28. |

| 70 | An example of which is given below in the case of the faculty of gladness. |

| 71 | atha kiṃsvabhāvā muditā tad ucyate • sauma(nasy)e(ndr)i[ya]svabhāvā, YL 153r2. |

| 72 | 問此四無量自性是何。 T 1545, p. 420b11; 問曰:無量體性是何? T 1546, p. 315a20; 問曰:無量等有何性? T 1547, p. 491a28. |

| 73 | For example, in the case of compassion, we may reconstruct: atha kiṃsva(bhāvā karuṇā tad ucyate avihiṃsāsvabhāvā vihiṃ)sāpratipakṣe(ṇa), YL 147v2–3. (“Now, what is the essence of compassion? It is said her essence is non-harmfulness due to counteracting harmfulness.”) Cf. YL 147R2–3 (Schlingloff [1964] 2006, p. 134). This corresponds to the position of other unnamed figures cited in the latest translation of the *Vibhāṣā alone: 有作是說。慈無量以無瞋善根為自性對治瞋故。悲無量以不害為自性對治害故。 T 1545, p. 420b18-20. (“There are those who make the claim: “Immeasurable friendliness has the good root of non-hate (adveṣa) as its essence due to counteracting hate (dveṣa) and immeasurable compassion has non-malice (avihiṃsā) as its essence due to counteracting malice (vihiṃsā).”) Of interest is that Saṃghabhadra affirms the same in his Nyāyānusāra (T 1562, pp. 768c29–769a13) and not the stance given in the two later versions of the *Vibhāṣā, which rather tell us: 慈悲俱以無瞋善根。為自性對治瞋故 T 1545, p. 420b11-12; 慈悲是無恚善根,對治於恚 T 1546, p. 315a21. (“Friendliness and compassion have the good root of non-hate as their essence due to counteracting hate.”) This latter is the more common. It is cited in the *Maitreyaparipṛcchopadeśa: 慈悲心體者,不瞋善根是。何以故?以對治瞋法故。 T 1525, p. 262c26-27 (“The essence of friendliness and compassion is the good root of non-hate because they counteract hate”); it is also the position generally stated in later works too: adveṣasvabhāvā maitrī. tathā karuṇā adveṣasvabhāvā, Abhidh-d 437 (“The essence of friendliness is non-hate. Likewise, the essence of compassion is non-hate”); adveṣasvabhāvā maitrī api karuṇā Abhidh-k-bh 8, 29c (“The essence of friendliness and compassion is non-hate”). The Vibhāṣā presents an entirely different view: 慈悲護,無貪, T 1547, p. 491a28-29. (“Friendliness, compassion and equanimity are non-greed (alobha).”) Such variances again make clear that the author of the Yogalehrbuch did not rely on any *Vibhāṣā available today but most likely another version, or indeed the yogaśāstra(s), whose own exposition notably corresponds to an alternative stance given only in the Abhidharmamahāvibhāṣā and the Nyāyānusāra, versions of which were present in Central Asia in the seventh century. What we are to conclude from this is not obvious, although the similar timeframe in which the manuscript of the Yogalehrbuch and the latter two works were penned could well be significant. |

| 74 | T 1545, p. 420c1-11. |

| 75 | The *Vibhāṣā defines the faculty of gladness as follows: 喜根云何。答依順樂觸所生心悅。平等受受所攝。是謂喜根。 T 1545, p. 732c2-3 (“What is the faculty of gladness? It is the mental delight that is produced upon an associated pleasurable contact. It is the same as feelings and is included in feelings; this is the faculty of gladness”); see also T 1546, p. 274c12-13. It is named as one of twenty-two faculties (indriya): the five sensual faculties of seeing, hearing, smell, taste and touch, the faculties of female, male, life, and mind, the five feelings of pleasure, displeasure, gladness, sadness and apathy, the good faculties of faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom, and the three pure faculties of what is known, to be known, and both (T 1545, p. 728c10-13). There was some debate among Sarvāstivādins concerning which of the twenty-two were to be considered real (Cox 2004, pp. 570–71), with only seventeen regarded as such (including the faculty of gladness) and five considered subsumable under others. For instance, the female and male faculties are classed as part of the faculty of touch (T 1545 730a29–730c5). |

| 76 | Other taxonomical methods were used by the early Sarvāstivādins, such as twelve perceptual domains (āyatana) or eighteen perceptual elements (dhātu), to relate oneself and the world (Dhammajoti 2015, p. 30ff). |

| 77 | These are two of six causes (hetu) named in the *Vibhāṣā, which are distinguished by the number of aggregates (skandha) in which they are included: 問此六因幾是五蘊攝幾非五蘊攝。答二唯四蘊攝除色蘊謂相應遍行因。三通五蘊攝謂俱有同類異熟因。一通五蘊及非蘊攝謂能作因。 T 1545, p. 108b21-24. (“Which of the six causes are included in five aggregates and which are not included in five aggregates? Two alone are included in four aggregates, excluding the aggregate of materiality, namely, cause by conjunction and by omnipresence. Three are included in all five aggregates, namely, cause by co-arising, identity, and ripening. One encompasses five aggregates up to what is not included in the aggregates, namely, the efficient cause.”) |

| 78 | sā tu sānuparivartā sasaṃprayogā parigṛ(hyamānā kāmāvacarā catuḥ)skandhasvabhāvā • r(ū)pāvacar(ā) paṃcaskandhasvabhāvā, YL 153r2-3. (“But including her accompaniments and conjunctions, her sphere is sensuality and essence four aggregates (or) her sphere is materiality and essence five aggregates.”) This sort of analysis is already found in early works of the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma, such as the Prakaraṇapāda in relation to absorption (T 1542, p. 746a27-b12), the immeasurables (T 1542, pp. 747c25-748b11), and other such entities that pertain to meditation. However, the specific formulation here cited by the Yogalehrbuch is somewhat central to the ontology of the *Vibhāṣā and is indeed first encountered at the very beginning of the work in the definition of metaphysics (abhidharma) itself: 問阿毘達磨自性云何。答無漏慧根以為自性一界一處一蘊所攝。一界者謂法界。一處者謂法處。一蘊者謂行蘊。若兼相應及取隨轉三界二處五蘊所攝。三界者謂意界法界意識界。二處者謂意處法處。五蘊者謂色蘊乃至識蘊。 T 1545, p. 2c23-28. (“What is the essence of abhidharma? It takes the faculty of pure knowledge (*anāsravaprajñendriya) as its essence, which is included in one perceptual element, the element of thoughts, one perceptual domain, the domain of thoughts, and one aggregate, the aggregate of conditions. Including the conjunctions and accompaniments, then three elements, the elements of mind, thoughts and mental cognition, two domains, the domains of mind and thoughts, and five aggregates, the aggregate of materiality as far as the aggregate of cognitions, are included.”) Such analysis is commonly applied to entities involved in absorption, such as non-hate (adveṣa), which is the essence of friendliness (maitrī) and compassion (karuṇā) (T 1545, p. 420b11-14), and non-greed (alobha), which is the essence of equanimity (upekṣā) (T 1545, p. 420c5-7), the practice on impurity (aśubhaprayoga) (T 1545, p. 206c11–20), the eight liberations (vimokṣa) (T 1545, p. 434b23-26), the eight abodes of overcoming (abhibhvāyatana) (T 1545, p. 438c6–9), and the ten abodes of totality (kṛtsnāyatana) (T 1545, p. 440b11-23). Similar phrasing is partially reproduced in later Sarvāstivādin works available in Sanskrit. Although this is not true of the immeasurables themselves, we can take the abodes of totality as an example. In the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya, these are described as follows: daśānāṃ kṛtsnāyatanānām aṣṭāv alobhasvabhāvatvād dharmāyatanena | saparivārāṇi tu pañcaskandhasvabhāvatvān manodharmāyatanābhyām | Abhidh-k-bh 1, 27. (“Eight of the ten domains of totality, due to having the essence of non-greed, are with the domain of thoughts. But together with their companions, they have the essence of five aggregates and are with the domains of mind and thoughts.”) Commenting on this, Yaśomitra (fl. seventh century) writes in the Abhidharmakośabhāṣyavyākhyā: katamāny aṣṭau pṛthivyaptejovāyunīlapītalohitāvadāta-kṛtsnāyatanāni tāni ca alobhasvabhāvāni apadekṣyante alobho ’ṣṭāv iti alobhaś ca dharmāyatane ’ntarbhavati tena tatsaṅgrahaḥ saparivārāṇi tu pañcaskandhasvabhāvatvān manodharmāyatanābhyāṁ kiṁ saṅgṛhītāni tasyālobhasya parivāro ’nuparivartirūpaṁ rūpaskandho vedanāsañjñe vedanāsañjñāskandhau cetanādayaḥ samprayuktā jātyādayaś ca viprayuktāḥ saṁskāraskandhāḥ vijñānaṁ cātra kalāpe vijñānaskandha iti pañcaskandhasvabhāvāni tāni bhavanti, Abhidh-k-bh-vy 56. (“What are the eight? The domains of the totalities of earth, water, fire and wind, and blue, yellow, red and white; these are said to be the essence of non-greed. Eight are non-greed: Non-greed manifests to the domain of thoughts but including these (eight) together with their companions, their essence is five aggregates, with the domains of mind and thoughts. What is included? The company of non-greed is accompanying materiality, which is the aggregate of materiality, the conjunctions of feelings and conceptions, which are the aggregates of feelings and conceptions, intentions, etc., and the disjunctions of birth, etc., which are the aggregate of conditions, and cognition, which in this here bundle is the aggregate of cognitions; these are the essences of five aggregates.”) Expectedly, perhaps, one example from the Abhidharmadīpa more closely reproduces the language of the *Vibhāṣā when defining absorption (dhyāna): samādhisvabhāvaṃ khalu paramārthena dhyānam | saparivāraṃ tu gṛhyamāṇaṃ pañcaskandhasvabhāvam | Abhidh-d 405. (“The essence of concentration, in the ultimate sense, is absorption. However, including its companions, its essence is five aggregates.”) |

| 79 | Commenting on the definition of the essence of joy, the *Vibhāṣā writes: 問若喜無量以喜根為自性者。品類足說當云何通。如說。云何喜無量。謂喜及喜相應受想行識。若彼所起身語二業。若彼所起心不相應行皆名為喜。豈有喜受與受相應。答彼文應說。謂喜及喜相應想行識。不應言受而言受者是誦者謬。復次彼論總說五蘊為喜無量自性。雖喜受與受不相應。而餘心心所法與受相應。故作是說亦不違理。 T 1545, p. 420b22-c1. (“If immeasurable joy takes the faculty of gladness as her essence, how is the Prakaraṇapāda (see T 1542, p. 718b25-c4) to be interpreted? Thus, it says: “What is immeasurable joy? Namely, joy and the feelings, concepts, conditions and cognitions conjoined (saṃprayukta) with joy, and what has co-arisen (samutthitaṃ) as the two activities of body and speech or as conditions disjoined from mind; all are called joy.” How is it that the feeling of joy is conjoined with feelings? This text should say: “The feeling of joy and concepts, conditions and cognitions conjoined with joy.” It should not say “feelings”, this word being an error in transmission. Moreover, this treatise generally says: “The five aggregates are the particular nature of joy”. Even though the feeling of joy is not conjoined with feelings, because the mind and other mental states are conjoined with feelings, what is said is not in error.”) See also T 1546, p. 315b2-9, T 1547, p. 491b-7. The quoted passage, which the *Vibhāṣā here corrects, is repeated verbatim in the Chinese translations of the Saṃgītiparyāya (T 1536, p. 392b12-14) and the Dharmaskandha (T 1537, p. 487a28-29), and is partially found in one Sanskrit fragment of the latter: api khalu muditā muditāsaṁprayuktā ca yā vedanā saṁjñā saṁskārā vijñānaṁ tataḥ samutthitaṁ /// —ttaviprayuktāḥ saṁskārā iyam ucyate muditā, Dsk 27r7-8 (Matsuda 1986). |

| 80 | Abhidh-k-bh 2, 23cd. |

| 81 | The Dharmaskandha lists the entities that co-arise with joy (muditāsahagata), such as the mind (citta) and mental cognition (manovijñāna), intention (cetanā), mental determination (abhisaṃskāra), attention (manasikāra), and resolution (adhimokṣa). T 1537, p. 487c8–14. A parallel passage for friendliness (maitrī) is attested in a Sanskrit witness: tathā samāpannasya yac cittaṃ manovijñānam idam ucyate maittrīsahagata(ṃ cittaṃ | yā cetanā saṃceta)nā abhisaṁcetanā cetitaṃ cetanāgataṃ cittābhisaṁskārā manaskarmma idam ucyate maittrīsahabhuvaṃ karmma (|) yaś cetaso ’dhimokṣo ’dhimuktir adhimucyanatāyam ucyate maittrīsahabhuvo ’dhimokṣaḥ (|) yad a(*pi tathā samāpannasya) vedanā vā saṃjñā vā cchando vā sneho vā manasikāro vā smṛtir vvā samādhir vvā prajñā vā itīme ’pi dharmmā maittrīsahabhuvaḥ (|) tat sarvva ime dharmmā maittrī cetaḥsamādhir iti vaktavyāḥ (|) Dsk 18r1-2 (Dietz 1984). (“For one so engaged (in the practice of friendless), mind and mental cognition are said to be the mind which co-arises with friendliness; intention (etc.,), what is intended, what concerns intention, mental determination, and attention are said to be action which co-arises with friendliness; and the resolve, resolution, and resolving of thought are said to be resolve which co-arises with friendliness’ Likewise, feeling, ideation, desire, love, attention, memory, concentration, and wisdom are phenomena which co-arise with friendliness. It should be said that all these phenomena are friendliness and concentration in thought.”) |

| 82 | Conjunction (saṃprayoga), or a conjoined cause (saṃprayogahetu), is itself a real entity (dharma) that governs the causal relations between the mind (citta) and other mental entities (caitasikadharma) and serves to explain how one simultaneously feels, conceives of, etc., one object (ālaṃbana) perceived by one perceptual basis (āśraya), such as the eye (cakṣus), at one time (kāla) (T 1545, pp. 79c06–80a17; summarised in Dhammajoti 2015, pp. 27, 175–77). This notion is already found in early works of the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma, such as the Prakaraṇapāda (T 1542, pp. 747b23–748b11). |

| 83 | It seems that the doctrine of momentariness was first elaborated in the *Vibhāṣā, though taken for granted and so not the subject of lengthy debate (Rospatt 1995, pp. 20–28). |

| 84 | An accompaniment (anuparivartaka) is a real entity and a kind of co-arising cause (sahabhūhetu). It is used to explain, on the one hand, the relations of the material world (rūpa), constituted by the co-mingling of the four great elements (mahābhūta), air, earth, fire and water, and, on the other, the relations between the mind and two kinds of non-mental entities that are said to be the accompaniments of mind (cittānuparivartin). First are the aforementioned conditions disjoined from mind (cittaviprayuktasaṃskāra) which determine the momentariness of all conditioned entities and are classified under the aggregate of conditions (saṃskāraskandha); this aggregate initially accounted for the role of intention (cetanā) in perception but was expanded in early works of the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma to include non-mental entities disjoined (viprayukta) from the mind but which co-arise with it (Cox 1995, pp. 66–74). Second are acts of body and speech that accompany mind (cittānuparivartakakāyavākkarman), which are of two kinds, restraint by absorption (dhyānasaṃvara) and pure restraint (anāsravasaṃvara), both co-arising with the mind in absorption, which itself entails the non-doing of (i.e., restraint from) certain immoral acts (T 1545, pp. 81b04–82b23; summarised in Dhammajoti 2015, pp. 174–79). For this reason, we similarly read the following: 問隨轉自性是何。答四蘊五蘊。欲界無色界四蘊無隨轉色故。色界五蘊有隨轉色故。 T 1545, p. 82b14-16. (“What is the essence of accompaniment? Four or five aggregates: four in the realm of sensuality and the realm of immateriality (ārūpaydhātu) because there is no accompanying materiality; five in the realm of materiality because there is accompanying materiality.”) |

| 85 | 又如所說。若身搖動成善惡性。花劍等動何不爾者。此亦不然。有根法異。無根法異。身是有情數攝。由心運動能表有善惡心心所法。花劍等不爾故。表無表決定實有。 T 1545, p. 635a7-11. (“Thus, it is said: “When the body moves it is good or bad in nature. Why are a flower, blade, etc., not so? They are not this way due to the difference in the presence or absence of faculties (indriya): a body includes indexes of sentience (sattvākhya), such that the movement of the mind can make known (vijñāpayitavya) a good or bad mind or mental state, but a flower, blade, etc., are not so.” Vijñapti and avijñapti are certainly real entities!”) We know this distinction was an issue for the author of the Yogalehrbuch, as the yogin is regularly said to apportion the world into indexes of sentience (sattvākhya) and indexes of insentience (asattvākhya), primarily in practices that involve the analysis of the self and other. Thus, as part of the practice on the elements (dhātuprayoga), when the yogin observes the six elements (dhātu) of earth, water, wind, fire, space and consciousness (another mapping of oneself and world), he first sees (paśyati) the four material elements that comprise his physical body (āśraya) and “Likewise the entire world as regards the bodies of all sentient beings and the indexes of insentience” (tadvat sarvasatv(ā)śr(a)y(e)ṣv as(at)v(ākh)y(eṣu ca kṛ)tsna(ṃ) lok(aṃ), YL 128R5–129V1). Similarly, he sees that his body is empty (śūnya) and “Just so the indexes of sentience and insentience” (evaṃ sarvasatvāsatvākhyam | YL 129V3). When practising equanimity towards the fiction of self (ātmaparikalpopekṣā), the yogin also divides up his own body (āśraya) with a knife and “Likewise separates out the entire ocean of sentient beings by apportioning the six elements as well as the index of insentience by apportioning five elements” (tadvad e(va ṣaḍdh)ātuvibhāgena kṛtsnaṃ satvasamudram avasthāpayanti asatvākhyaṃ ca paṃcadhātuvibhāgena, YL 160V5). I would like to here thank Abe Takako for pointing out that a similar distinction between materialities (rūpa) considered as sentient (sattvasaṃkhyāta) or insentient (asattvasaṃkhyāta) is also found in the Śrāvakabhūmi in the context of observing, in meditation, what is respectively within (adhyātma) and without (bahirdhā) the body (kāya) (Śr-bh II, 180–190, Śrāvakabhūmi Study Group 1998). |

| 86 | T 1545, p. 634c28-29. |

| 87 | These denote the first seven of the ten base courses of action (mūlakarmapatha): 三惡行者。謂身惡行。語惡行。意惡行。云何身等惡行。如世尊說。何者身惡行。謂斷生命。不與取。欲邪行。何者語惡行。謂虛誑語。離間語。麁惡語。雜穢語。何者意惡行。謂貪欲瞋恚邪見。應知此中世尊唯說根本業道所攝惡行。 T 1545, p. 578a21-26. (“There are three bad acts, namely, bad acts of the body, bad acts of speech and bad acts of mind. What are the bad acts of the body, etc.? Just as the Blessed One teaches: “What are the bad activities of the body? Killing, stealing, and sex. What are the bad activities of speech? Lying, maligning, offending and prattling. What are the bad activities of the mind? Greed, malice and false view.” One should here know that the Blessed One only said that these bad acts are included in the base courses of action.”) Good courses of action are simply defined by the negation of their negative counterparts, such as non-killing, non-lying, non-greed and so on (T 1545, p. 581a7-17). |

| 88 | In defense of avijñapti, whose apprehensibility and reality were denied by the Dārṣṭāntikas on both causal and phenomenal grounds, as a lie, essentially, like one who seeks to convince others that they are adorned with heavenly robes but are in fact naked, like the simile of The Emperors Clothes (T 1545, p. 634b23-c8), the Vaibhāṣikas resort to scripture: 如契經說。色有三攝一切色。有色有見有對。有色無見有對。有色無見無對。若無無表色者。則應無有三種建立。 T 1545, p. 634c14-17. (“According to scripture, all materials are included in three states of materiality: materials which are visible and obstructive, invisible and obstructive, and invisible and unobstructive. If there were no avijñaptirūpa, then the three kinds of states (bhava) would not be given.”) The latter is said to be invisible and unobstructive to the senses, insofar as it remains imperceptible and latent until it later materialises, such as when one wishes at one time to kill another but only later acts upon it, as was the case with King Ajātaśatru’s initial intention to kill his father and his later doing of the deed (T 1545, pp. 634b21–635a29). It is also said that avijñapti is unlike other kinds of materiality, which are knowable by either their colour (rūpa), their shape (saṃsthāna), or both, and so it is named as a specific kind of materiality that belongs to the domain of the thoughts (T 1545, pp. 634c29–635a7). However, these phenomenal properties allowed for other interpretations, particularly among certain groups of yogins of the middle of the first millennium, who attributed the same to the objects (viṣaya) of meditation and consequently renewed debates in scholastic circles on whether avijñapti should indeed be considered a real entity (Greene 2016b, p. 122ff). We shall have cause to turn to this issue again, for the phenomenology of vijñapti and avijñapti bears on the nature of certain objects described in the practice of joy. |

| 89 | Restraint by absorption is also presented as the non-doing of the seven immoral acts of body and speech (T 1545, p. 684c11-15). Several opinions are recorded in the Vibhāṣā as to why restraint by vow differs from restraint by absorption, with the former, for instance, said to be gross and the latter subtle, one to derive from vijñapti and the other avijñapti, and one to arise due to others, such as the monastic community (saṃgha), and the other due to one’s mind alone (T 1545, pp. 622b23–623c10). |

| 90 | The Vaibhāṣikas define two kinds of restraint as accompaniments. First is restraint by absorption, otherwise termed “restraint which co-arises with concentration” (dingjuyoujie 定俱有戒, *samādhisahabhāvasaṃvara), which may be impure (āsrava) or pure (anāsrava), insofar as it may be the result of the meditation of an ordinary person (pṛthagjana) who is not yet free of the passions (avītarāga) and has some delusion (viparyāsa), for instance, about the object of his resolution (adhimukti), like the skeleton of the practice on impurity or the sentient being of the immeasurables (see below). Second is pure restraint (anāsravasaṃvara), or restraint that co-arises with the path (daojuyoujie 道俱有戒, *margasahabhāvasaṃvara), which differs from the former in arising not as a result of the four elements of materiality but by the power of the pure mind of a noble one (arhat) who is totally free of the passions (vītarāga). Restraint by vow is said to not accompany the mind because it is enacted in the realm of sensuality and so does not belong to the concentrated ground (fedingjie 非定界, asamāhitabhūmi), a ground of cultivation (xiudi 修地, *bhāvanābhūmi), nor to the ground upon which the passions have been removed (lirandi 離染地, vītarāgabhūmi) (T 1545, pp. 82c07–84a29). A relevant passage in Sanskrit occurs in the Abhidharmakośabhāṣyavyākhyā: catuḥpaṃcaskaṃdhasvabhāvānīti. kāmāvacaram anuparivartakarūpābhāvāc catuḥskaṃdhasvabhāvaṃ vedanāsaṃjñāsaṃskāravijñānaskaṃdhasvabhāvam ity arthaḥ. ūrdhvabhūmikāni tu paṃcasvabhāvāni dhyānasaṃvaralakṣaṇarūpaskandhasvabhāvāt, Abhidh-k-bh-vy 634. (“The essence (of the grounds) is four or five aggregates—The meaning is that the sphere of sensuality, due to lacking accompanying materiality, is the essence of four aggregates, the essence of the aggregates of feelings, conceptions, conditions and cognitions. However, the higher grounds are the essence of five aggregates because of the essence of the aggregate of materiality which has the quality of restraint by absorption.”) |

| 91 | Cox has shown that bhāva, in early works of the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma, such as the Saṃgītiparyāya, and in one Gāndhārī fragment, which lays out several of that school’s positions, appears to denote the changing “mode of existence” of an entity through the past, present or future, as opposed to its unchanging essence (svabhāva), which is atemporal. However, the difference between the two was apparently not so clear cut. In the *Vibhāṣā, it is said that Dharmatrāta clearly distinguished bhāva (lei 類) from svabhāva (zixing 自性) along these lines, but the Vaibhāṣikas were themselves reluctant to fully adopt his view, despite many passages suggesting they in fact did, until it was properly formalised by Saṃghabhadra, in his Nyāyānusāra, for whom the difference lay in the efficacy (kāritra) of an entity being in time as opposed to the potentiality (sāmarthya) of its essence (Cox 2004, pp. 567–68; 2013, pp. 56–58). That the distinction between “essence” and “being” is upheld in the Yogalehrbuch, as indeed kāritra and sāmarthya seem to be, as noted above, may suggest an influence from these later speculations. |

| 92 | bhūmi(taḥ kāmadhātau dh)y(ā)nadvaye ca tatra sau(manasyend)[r](i)y(a)sadbhā(vāt||) YL 153r3–4. (“As regards the ground, (she is) on the realm of sensuality and the (first) two absorptions because there the faculty of gladness has actual being.”) This differs from the other immeasurables, whose grounds are rather said to be seven (saptabhaumā): on the realm of sensuality (kāmadhātau), the not-yet-arrived (anāgamye), the intermediate absorption (dhyānāṃtare), and the four absorptions (caturṣu dhyāneṣu) (YL 140V1, 147R4, 155R1). Although this corresponds to the affirmed position in the Vibhāṣā (T 1547, p. 491b16-17) and the Abhidharmamahāvibhāṣā (T 1545, p. 421a1–2), the latter also records another scheme to name ten stages, including the afore-listed seven in addition to four adjacent (sāmantaka) states (T 1545, p. 421a3–4), which are incidentally those affirmed in the Abhidharmavibhāṣā (T 1546, p. 315c3-4). The Maitreyaparipṛcchopadeśa (T 1525, p. 263a20–22) and the Abhidharmadīpa (Abhid-d 429) contrarily name six, excluding the realm of sensuality, which in this case corresponds to the view upheld in the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya (T 1558, p. 150c16-20), clarifying that the difference between the six grounds and the seven or ten grounds is due to the respective exclusion or inclusion of unconcentrated (asamāhita) practice on the ground of the realm of sensuality. Some therefore only viewed the immeasurables as a concentrated (samāhita) mode of practice to be realised on the ground of absorption (dhyāna). For further discussion of the relationship between the grounds and the four immeasurables in both Sarvāstivāda and Yogācāra treatises, see Abe (2023, p. 40ff). |

| 93 | There are numerous canonical presentations of what attributes characterise the four absorptions (Cousins 1973, pp. 122–25; Kuan 2005), and the *Vibhāṣā assembles most of these together in one listing: 謂初靜慮有五支。一尋二伺三喜四樂五心一境性。第二靜慮有四支。一內等淨二喜三樂四心一境性。第三靜慮有五支。一行捨二正念三正慧四受樂五心一境性。第四靜慮有四支。一不苦不樂受二行捨清淨三念清淨四心一境性。 T 1545, p. 412a21-26. (“Namely, the first absorption has five attributes: rough perception (vitarka) and fine perception (vicāra), rapture (prīti), pleasure (sukha) and one-pointedness of mind (cittaikāgratā). The second absorption has four: inner calm (adhyātmasamprasāda), rapture, pleasure and one-pointedness of mind. The third absorption has five: equanimity (upekṣā), correct awareness (samyaksṃrti), correct comprehension (samyaksamprajāna), feeling pleasure, and one-pointedness of mind. The fourth absorption has four: neither the feeling of sadness (daurmanasya) nor gladness (saumanasya), purity of equanimity (upekṣāpariśuddhi), and one-pointedness of mind.”) |