Abstract

This article addresses the epistemic and political problem of self-referentiality in theology within the context of post-secular societies as a demand for public relevance of faculties of theology within the 21st-century university. It focuses on the epistemological emergence of public theology as a distinct knowledge, such as human rights, and ecological thinking, contributing to the public mission of knowledge production and interdisciplinary engagement. This study applies Michel Foucault’s archaeological and genealogical methods in dialogue with Michel de Certeau’s insights into the archaeology of religious practices through a multi-layered analytical approach, including archaeology of knowledge, apparatuses of power, pastoral government, and spirituality as a genealogy of ethics. As a result of the analysis, it examines the historical conditions of possibility for the emergence of a public theology and how it needs to be thought synchronously with other formations of knowledge, allowing theology to move beyond its self-referential model of approaching dogma and the social practices derived from it. This article concludes programmatically that the development of public theology requires an epistemological reconfiguration to displace its self-referentiality through critical engagement with a public rationality framework as an essential task for the public relevance and contribution of theology within contemporary universities and plural societies.

1. Introduction

This article explores the need for an archaeology of theological knowledge in the face of the challenge of epistemic self-referentiality in post-secular societies, where the public presence of religion reappears in an ambiguous and contested form. In this context, theological faculties face a growing demand to justify their public and academic relevance within 21st-century universities, which are characterized by an ideal of critical, ethical, and pluralistic rationality.

The central problem addressed is that theology, when confined to its confessional and institutional self-referentiality, becomes epistemically isolated and politically ineffective, reproducing forms of identity closure and losing the ability to contribute to public debate. While self-referentiality has been described by Niklas Luhmann (1984) as a legitimate mode of systemic functioning, the authors’ position here is that this characteristic can hide the historical and political conditions that shape knowledge, contrasting at the same time with proposals for an ‘outgoing theology’ [theologia in exitu]1 committed to listening and interdisciplinarity and social transformation. It is in this context that the task of an archaeology of theological knowledge arises, but at the same time, how this knowledge relates to power relations, and thus how relations are established with the genealogy of power in the context of theological knowledge production and the social practices that derive from or sustain it, also arises.

The aim of this article is therefore to outline elements that can contribute to the perception of the public relevance of theology based on the challenge of rethinking its epistemological foundations in dialogue with the public rationality that constitutes the basis of contemporary universities. However, this critique of self-referentiality does not imply a rejection of dogmatic theology itself. Instead, it draws attention to the dangers of theology becoming isolated within its own systems and losing the ability to address contemporary issues. In this sense, public theology is not proposed as a replacement for traditional theological approaches but as an epistemological complement to them. To this end, Michel Foucault’s archaeological–genealogical method is used to analyze theological knowledge-power in order to outline the need for an epistemological reconfiguration of theology, or more precisely, an archaeo-genealogy of public theology.

Although some contributions, such as Bernauer and Carrette (2016), address Foucault’s relation to religion, his reflections on religion and culture remain largely unexplored in the humanities. In this sense, there are works that correlate M. Foucault with theology, reflecting on the political positioning inherent in religious experience, not only in the formulation of an apparatus2 of control but also in the genealogy of ethics and political spirituality, offering a new critical hermeneutic for theology, as was the case with Tran (2011) and Chevalier, who particularly explored the possibility of an “anarchéologie” in the relationship between Foucault and Christianity (Chevallier 2024). The publication of the volume “Histoire de la sexualité: Les aveux de la Chair” (Foucault 2018b), dedicated to the study of Christian authors, also sheds new light on research on Foucault and theology. Carrette has also compiled Foucault’s writings on religion, opening up new possibilities for reading the French philosopher and the issues surrounding religion (Foucault 1999).

However, the French philosopher does not offer a precise theory of religion, but religion is intimately related to culture, and as such, its value for individuals and groups can undergo the same changes as a given culture, while elements of the religious phenomenon form part of the structures of a culture’s way of being, even when secularized, as is the case with Western culture, on which Foucault focuses his archaeological and genealogical exercise (Wuthnow et al. 1984, p. 162).

Furthermore, the analysis of the epistemological implications from the perspective of Michel Foucault’s archaeo-genealogical method aims to conceive a ‘critical hermeneutics’ of theology, as proposed by Bernauer and Carrette (2016, p. 4), and what this might become in the construction of a public theology in the context of the emergence of a commitment of theology to a public agenda.

To this end, this work operates with several facets of Foucauldian tools. The first, archaeological, describes the historical conditions that made theological knowledge possible in modernity. The second, genealogical, identifies the devices that structure the relationship between power and knowledge in their institutional practices, especially in theological faculties. The third focuses on the genealogy of pastoral power and its forms of subjectivation and how they have been used by political theology projects to legitimize political actors. Finally, the fourth level focuses on an ethical and spiritual reading of forms of resistance, proposing a ‘critical spirituality’ as a condition of possibility for public theology. For this purpose, this article also revisits an ‘unfinished dialogue’ between Foucault and Michel de Certeau, whose reflections deepen the archaeological task of revealing the persistence of religion as a structure of thought in modern discursive practice (Petit 2020).

The aim is to understand how the discursive and non-discursive practices of theology have been shaped by the relations between knowledge and power and by the historical conditions of possibility, highlighting the potential of theology to become a public and critical knowledge. To this end, we propose an archaeo-genealogy of theological knowledge-power with a view to constructing a public theology, taking into account the place of theology in contemporary universities, grounded in public rationality and effective contribution to the common good. This task does not aim to replace the model of confessional or dogmatic theology but rather to propose an alternative rationality for the production of theological knowledge from the place where it is located, namely within the contemporary university and its task of producing critical and public knowledge.

2. Self-Referentiality as an Epistemological and Political Problem

Theological self-referentiality is one of the main epistemological and political challenges for the constitution of theology as a field of public relevance within contemporary universities. It is a phenomenon which, by privileging hermeneutical self-referentiality and by closing itself off to its own traditions and categories, runs the risk of confining theology to its confessional dimension, thereby compromising its ability to dialogue with public rationality and to contribute to the critical formation of plural societies.

2.1. The Insufficiency of the Hermeneutics of Secularization

The notion of post-secular societies highlights the insufficiency of the theory of secularization as a linear decline of religion. Rather than disappearing, the religious phenomenon is reappearing in the public sphere in new forms of expression and engagement.

This return, however, does not imply the restoration of the theocratic model, nor the permanence of religion in the private sphere. What is emerging is a pluralist scenario in which different rationalities compete for legitimacy in defining the common good, which demands a revision of the classical division between public and private (Lambert 2000).

In this context, religion reappears in an ambiguous form: sometimes as a promoter of dialogue and public agendas, such as the ecological agenda, and sometimes as a vector of exclusion and identity closure. This dualization of religion poses a challenge to the theological field to develop a language capable of critically engaging with public rationality and contributing to the construction of democratic and pluralistic societies.

2.2. The Dualization of Religion and the Crisis of Public Rationality

The dualization of religion refers to the coexistence of two paradoxical movements typical of so-called post-secular societies: on the one hand, openness to pluralism and commitment to universal causes, as Jürgen Habermas recognizes when he values religious traditions as sources of meaning (Habermas 2009); on the other hand, the use of religion as a tool for closing off identity and justifying exclusionary and authoritarian projects. This tendency, accentuated in advanced modernity (Campiche 2010), calls for a complex concept of religion capable of reflecting multiple articulations with different social fields (Hervieu-Léger 1999).

Based on longitudinal research on values in Europe, Yves Lambert distinguishes three basic categories: the religious (meta-empirical realities), the axiological (ethical values), and the ideological (socio-political representations). According to him, religion does not operate in isolation but in conjunction with ideology and axiology, which allows one to understand the tensions between religion and politics not as a binary opposition but as the result of discontinuities between social structures and subjective experiences (Lambert 2000).

The notion of ‘public religion’ proposed by José Casanova (1994) helps to understand the reconfiguration of relations between religion and society. However, perhaps it proves insufficient to deal with the complexity and constitutive ambiguity of the religious presence in contemporary societies. By privileging the integrative aspect of the religious phenomenon, the category tends to mitigate the effects of its political instrumentalization and the forms of identity closure that characterize contemporary reality. By uncritically adopting this notion, theology runs the risk of reinforcing a normatively positive image of public religion without taking into account its structural ambivalences.

In this scenario, self-referential theology, when it operates as an epistemic immunity, can foster polarization and reinforce political messianism, as Carl Schmitt described in his notion of ‘state of exception’, conceived as divine intervention, and through the formulation of state sovereignty as a secular version of papal infallibility, legitimizing authoritarian power structures as ‘uniformisation’ (Gleichschaltung) to eliminate dissonance (Schmitt 1996, p. 42).

2.3. The Institutionalization of the Epistemic Self-Referentiality of Theological Faculties

For the most part, the presence of theological faculties in contemporary universities is not the result of full recognition as scientific knowledge on an equal footing with other academic disciplines. On the contrary, this permanence is essentially due to the concordats and diplomatic agreements signed between national states and historic churches, which guarantee the institutional protection of theology, albeit on the margins of the modern and critical epistemological model of the human sciences.

This legal and political structure has consolidated an institutionalized self-referentiality that often operates without requiring conformity to criteria of public rationality. The concordats do not exactly oblige theology to submit to the methodological, critical, and intersubjective requirements that govern the scientific field, which, in many cases, allows it to function as a transposition of seminary theology into the university space, maintaining institutional purposes, clerical formation logics, and a strictly confessional rationality.

This state of affairs is most evident in southwestern Europe, where theology has been formally excluded from public higher education systems and relegated to confessional institutions. France, Spain, and Italy exemplify this process, which resulted from liberal and secular reforms between the 19th and 20th centuries (Baubérot 2000; Chadwick 1990). The exceptions are, in particular, legal arrangements: Portugal, with the creation of the Universidade Católica Portuguesa under the 1940 Concordat (Holy See 1940); Malta, with the maintenance of the Faculty of Theology as part of the public university since the 1988 Concordat, reaffirmed in 1993 (Holy See 1993); and the Alsace–Moselle region of France, where the Napoleonic Concordat of 1801 is in force and was not revoked after the Treaty of Versailles (Baubérot 2000; Prost 1997).

The German model, adopted by the University of Strasbourg, is the most consolidated. Here, theology is recognized as a scientific discipline under the regime of the State Church Law. The Catholic and Protestant theological faculties operate as ‘res mixta’ under dual governance: state (in terms of university funding and regulation) and church (in terms of doctrinal orthodoxy and clergy training) (Wissenschaftsrat 2010). While this configuration ensures institutional stability, it also runs the institutional risk of reinforcing the self-referential logic of theology and does not necessarily make feasible its openness to public rationality, interdisciplinary critique, and wider academic debate. Moreover, this model has been the target of recurrent criticism from parts of the university and civil society, especially in a context of budgetary austerity, due to the low number of students enrolled and the high cost of maintaining theological faculties. Such criticism calls into question their academic and financial viability and reinforces the contemporary challenge of transforming theology from a regime of confessional exception to a space of public dialogue that actively and recognizably contributes to the plural construction of knowledge. This is not a matter of the individual abilities of distinguished theologians, but rather a structural problem concerning the way theology is integrated into the contemporary scientific and university systems.

The Wissenschaftsrat’s Criticism of Theological Faculties (2010–2011)

Even the most well-established models for integrating theology into public universities today face pressures related to their academic and financial sustainability. The steady decline in the number of students enrolled in theology courses, coupled with the decline in religious vocations and the low employability outside the church context, raises doubts about the viability of these programs, especially in performance and productivity-driven systems.

This situation has led to debates about the closure or merger of theological faculties with other fields, such as philosophy or religious studies, and to critical evaluations by accreditation agencies, which point to shortcomings in interdisciplinarity, internationalization, and dialogue with other scientific fields. Against this background, the German Council of Science and Humanities (Wissenschaftsrat)—the German government’s main advisory body on science and higher education—published a report in 2010/2011 that reaffirms the importance of theological faculties for ethical education and interreligious dialogue but also offers sharp criticism of their current structure, especially on issues that may be related to the problem of epistemic self-referentiality. The main points include the following (Wissenschaftsrat 2010):

- The need for interdisciplinary openness, encouraging dialogue with human and social sciences such as philosophy, sociology, and the history of religions;

- The tension between academic autonomy and ecclesiastical supervision, which compromises scientific freedom in the name of doctrinal orthodoxy;

- The inclusion of Islamic theologies in the German theological academic community in recognition of the religious diversity in German society;

- Resistance to modernization, with closed corporate practices and fear of losing ecclesiastical control.

Despite their institutional role, and the excellent work carried out by various theologians, theological faculties continue to occupy a peripheral and often tolerated position, without fully integrating the epistemological principles of the public sciences. The maintenance of an operationally closed logic, legitimized by concordats or regimes of exception, perpetuates a self-referential view of the religious phenomenon that does little to confront the contemporary dualization of religion—between openness to pluralism and identity closure.

Rather than offering theology the conditions for a critical and mediating role in the pluralist public sphere, the institutionalization of self-referentiality accentuates its difficulty in positioning itself in the face of the ambivalences of the religious in contemporary society.

2.4. The Limits of Systemic Self-Referentiality in Niklas Luhmann

Niklas Luhmann (1927–1998) defines epistemic self-referentiality [Selbstreferentialität] as the capacity of social systems to generate meaning and validate knowledge through their own operations without recourse to external legitimation (Luhmann 1995).

From Luhmann’s perspective, social systems such as science, politics, and law are operationally closed and self-referential systems. This means that each of these systems defines and organizes itself according to its own internal codes and rules and is able to determine what is relevant or true based on its own communicative operations (Luhmann 1984). Science, for example, operates by defining the validity of knowledge on the basis of internally established criteria without the need for legitimation from outside this specific system (Luhmann 1989). This self-referential autonomy allows the system to constantly adapt, reproduce, and modify itself according to its evolutionary needs (Luhmann 1995). For science, this means that knowledge is continuously constructed through observations and theories that are internally related and that the scientific system uses its own operations to distinguish between information that is included and excluded from the field of knowledge (Luhmann 1984). Self-referentiality thus becomes the key to the self-reproduction of systems and the continuous construction of a self-validating body of knowledge.

For the German sociologist, epistemic self-referentiality does not lead to the ‘self-sufficiency’ of self-referential systems, which would imply a detachment from concrete reality and a lack of sensitivity to external influences. The point for Luhman is not that systems cannot be influenced by the environment but that responses to external stimuli are always processed according to the system’s internal rules (Luhmann 1997) and, therefore, do not exclude the possibility of interaction with the environment but define how this interaction is understood and integrated into the system’s logic. Self-referentiality guarantees the consistency and continuity of systems, allowing them to adapt to changes in the environment without losing their functional identity (Luhmann 1995). Thus, contemporary society should be understood as functionally differentiated, where different social systems are self-referential and do not communicate with each other directly but only through ‘structural coupling’ [Strukturelle Kopplung] (Luhmann 1997). Self-referentiality thereby does not imply complete isolation but rather the creation of meaning from an endogenous perspective without merging their internal logics (Luhmann 1995).

Structural couplings enable systems to interact functionally while preserving their operational autonomy. Each system interprets external influences through its own internal logic without merging with others. For example, science and politics may be coupled when scientific research informs policy decisions, yet both maintain distinct criteria of validation. Such couplings are essential for coordinating differentiated systems in contemporary society, allowing interdependence without compromising specificity.

Like any other system, theology organizes itself and defines its epistemological limits through a self-referential logic. In this way, theology would be a construction that operates internally, responding to the environment in a way that is filtered through its own criteria, thus guaranteeing its continuity and consistency over time.

In this sense, in a functionally differentiated society, theology would have a specific role and would not mix directly with other systems, such as science or politics, except in structural couplings. Thus, theology is part of a differentiated system, namely the religious system, which deals with questions of ultimate meaning and offers answers to existential uncertainties that cannot be satisfactorily addressed by other social systems.

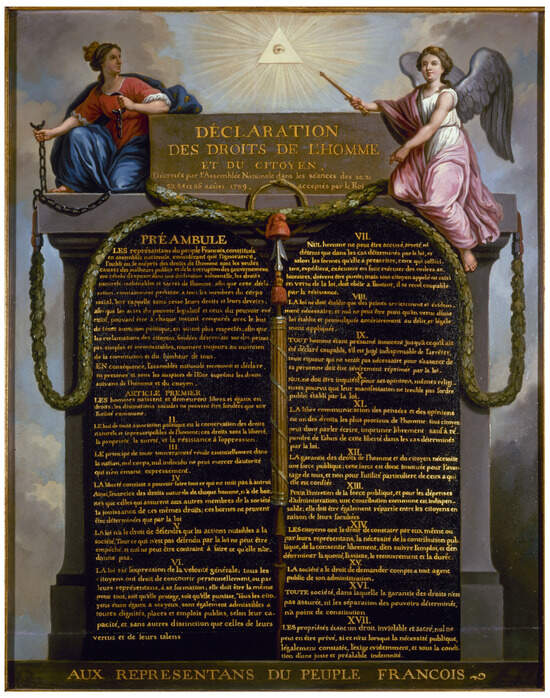

However, to the extent that theological knowledge can be found in modern universities, it is located in the university system, which functions as a link between the religious system and the scientific system of society. In addition to the procedural requirements that imply such a place, there is a fundamental element that is epistemological recognition by the scientific system, which, in terms of the modern university, implies thinking and producing theology according to the criteria of public rationality. With the rise of modern epistemology, theology was relegated to the margins of public universities due to its dependence on Revelation, as a structuring category of its discursive practice. Its institutional survival often depended on concordats with the state, which secured its formal place without guaranteeing epistemological recognition (Harrison 2015; Davie 2002). Movements such as the Enlightenment and the French Revolution promoted a vision of education divorced from religious world view as essential to the formation of rational and free citizens (Chadwick 1990).

In this context, the historical presence of theological faculties in medieval universities and their incorporation into modern universities was only possible through these agreements with modern states, and in a number of contexts, they still suffer, to some extent, from a lack of effective epistemological recognition of the scientific fields that make up the academic community.

The question that arises, therefore, goes beyond its existence in public or private universities, which would be institutional forms of structural coupling between religious and scientific systems, but is linked to the recognition (or not) of theology as knowledge accepted by the scientific community and the consequent professionalization (or not) of its epistemic subject, namely the theologian, on an equal footing with any other researcher in terms of his contribution to the public task of producing knowledge for the common good and critical awareness.

In this case, the concept of self-referentiality is not sufficient to promote the effective integration of theology into the set of disciplines, since it favors the epistemic isolationism of theology, which reinforces the intensification of the privatization of faith, and even the actions of religious communities in public arenas, with the aim of strengthening an identity bloc logic, rather than a commitment to a pluralist project of society, as can be seen in a series of emerging radical speeches (Teixeira et al. 2022).

This is precisely where the criticism of self-referentiality comes in, from the distorting effect it can potentially have on the notion of academic autonomy, leading precisely to academic isolation, where the study of theology is limited to an internal, hermetic approach, disconnected from the “signs of the times” (Pope Francis 2017, n. 1). Francis criticizes the tendency of a theological discourse that does not engage with the challenges and needs of the contemporary world, remaining closed in intestinal discussions or in the repetition of formulas. This results not only in a pastoral disconnection but also in a lack of interdisciplinary dialogue, which translates into an approach that ignores the complexity of the contemporary world and fails to respond to the urgent questions of the present, especially the growing conviction in which the “planet is a homeland and that humanity is one people living in a common home”: “Recognizing this interdependence ‘obliges us to think of one world with a common plan’” (Pope Francis 2017, n. 4, d). This common plan demands a translation for a common language, which, for theology, can mean translating into a public language to foster the cross-disciplinarity between different fields of knowledge, as well as believers from different traditions and non-believers.

In this sense, Luhmann’s analysis does not take into account the relationship between the production of scientific knowledge and scientific policies, insofar as this involves analyzing the political issues involved in the formation of the university system, on the one hand, and the movement to accommodate theology through diplomatic tolerance that benefits from it, on the other.

Although Niklas Luhmann’s theory of social systems offers a sophisticated descriptive model for understanding the autopoietic and self-referential functioning of differentiated social systems, it proves inadequate for explaining the dynamics that characterize the dualization of religion in contemporary societies and its impact on theology. It does not allow the problematization of the tensions and ambiguities inherent in the public presence of religion, which oscillates between a logic of pluralistic openness and identity closure. Similarly, theological self-referentiality, conceived as a legitimate operation of systemic closure, as described by Luhmann, can become a mechanism for preserving the identity of the religious system but without offering critical instruments for assessing when such closure ceases to be a functional condition and turn into an epistemological isolation, critical immunity, or even the basis of exclusionary and ideological practices.

2.5. The Proposal for a Theology That Goes Forth and the Problem of Self-Referentiality

The pontificate of Pope Francis has centered on the call for a “Church going forth”, which presupposes the production of a theology going forth [theologia “in exitu”] (Pope Francis 2023, n. 3). This perspective calls for a theology that renounces self-sufficiency and institutional comfort to engage with the world and its urgent challenges. Francis, as a pastor of existential and geographic peripheries, urges theologians toward an incarnate, compassionate presence. This movement unfolds ad extra, in ecological reflection through Laudato si’, and ad intra, through synodality as a practice of listening and unity in diversity. In both directions, theology must transcend its hermeneutical boundaries.

Francis reiterates the need for a theologia in exitu—a theology willing to leave its comfort zone and risk encounter. In Evangelii Gaudium, he prefers a church “bruised and dirty” from engagement over one “sick from closure” (Pope Francis 2013, nn. 49, 20). This spirituality, rooted in the face of the other, calls theologians to “walk with the people” and respond to the concrete challenges of humanity (Pope Francis 2015b). In Laudato si’, theology becomes a prophetic voice for ecological conversion and human dignity, engaging in transdisciplinary dialogue toward the common good and the goals of the 2030 Agenda (Pope Francis 2015a, n. 201). The whole proposal of synodality is not only a method of governance but a true spirituality of encounter, listening, and discernment. The Synod of the Amazon was an example of this practice, placing the voices of traditional communities, often ignored by hegemonic speeches, at the center. The Amazon itself, as a complex reality, is presented as a locus theologicus (Pope Francis 2020, n. 57).

At the opening of the International Theological Congress of the Dicastery for Education and Culture in December 2024, Francis invited theologians to “help theology to rethink the way it thinks”, where rethinking is linked to “moving beyond simplification” to face the complexity of reality. This requires that theology be “fermented” by interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity, which calls for theology to be an “open house” and for “theology to be accessible to all” (Pope Francis 2024).

Francis’s theology of going forth is often invoked to respond to the theoretical maturity of these commitments—to help think and discern reality and not be limited to sterile debates but closely linked to the concrete needs of humanity, embracing the complexities and contradictions of contemporary life. In this sense, for Francis, the place of the theologian is fundamentally at the frontier (Pope Francis 2015b).

In the introduction to the Apostolic Constitution Veritatis Gaudium on Ecclesiastical Universities and Faculties (Pope Francis 2017), these pastoral questions are given an epistemological translation and reaffirmed in the motu proprio Ad theologiam promovendam in which Francis stated about the transdisciplinary nature of theology:

“This relational dimension characterises and defines, from an epistemological point of view, the status of theology, which is driven not to close itself off in self-referentiality, leading to isolation and insignificance, but to see itself as part of a network of relationships, first and foremost with other disciplines and other fields of knowledge” [free translation].(Pope Francis 2023, n. 5)

Outgoing theology stands in contrast to a self-referential model that views theology as a “sacred science” concerned primarily with Revelation, directed to the priestly ministry, and placed above other forms of knowledge, as in Sapientia Christiana (Pope John Paul II 1979, III). Without ceasing to reflect its commitment to the theological tradition, an outgoing theology is called “from an epistemological point of view” to a transdisciplinary “relational dimension” to “know how to use the new categories approached by other knowledges” and to adopt the attitude of a “courageous cultural revolution”. Theology that goes forward urges the very ‘status of theology’ not to ‘close in on itself in its self-referentiality, which leads to isolation and insignificance’ (Pope Francis 2023, n. 5). This article addresses the criticism formulated by Pope Francis in his ecclesiastical teachings, in line with the principles of Catholic social teaching. Public theology, as proposed here, is not just a reflection on public issues but a theological discourse that emerges through public interaction. From this perspective, criteria of truth are not defined solely by internal coherence or dogmatic authority but also by the capacity of theology to illuminate, interpret, and transform the world in which it is situated. As a form of contemporary public knowledge, it requires theology to engage with the emerging semantics of a body of knowledge shaped by a complex group of relations that function as a rule for the epistemological conditions of its historical context. Here, the focus of public theology is on sharing the historical and discursive conditions that led to the emergence of knowledge considered scientific in modern times.

Michel Foucault’s methodological proposal, especially in the context of the archaeology of knowledge, offers a fruitful way to face the challenge of the dualization of religion in contemporary societies. Instead of interpreting religion solely as a functionally differentiated system, as Luhmann does, Foucault offers analytical tools and hypotheses that can help analyze religious formations as historically situated discursive practices intersected by relations of knowledge and power. His approach makes it possible to show the limits of problematizing religion through the lens of ideology and axiology and to understand it from the point of view of a ‘bundle of relations’ between knowledge whose rationality can be grasped through the order of speech of a given time.

3. The Task of an Archaeo-Genealogy of Theological Knowledge

Giorgio Agamben defines archaeology as the identification of “signatures” that shape how disciplines construct and perpetuate meaning. These marks, inherited from historical tensions, continue to structure contemporary regimes of truth (Agamben 2019, p. 44). Taking up and extending the archaeology proposed by Michel Foucault, Agamben emphasizes the relevance of this method for understanding the apparatuses that organize contemporary experience and the regimes of truth that accept or exclude certain practices of knowledge. In this sense, the archaeological task is not limited to a work of historical excavation but is presented as a critical method for thinking about knowledge—such as theology—in its constitutive relationship with the exercise of power and its possibilities for re-signification in the present.

While Luhmann describes knowledge systems as self-referential, Foucault shows that knowledge is always embedded in power relations that define what can be said and thought through mechanisms of control, exclusion, and disciplining of speech (Foucault 1971). There is no knowledge that is completely autonomous, because its conditions of possibility are historically determined by the power games that determine what can be said and thought at any given time.

From this perspective, social systems cannot be understood as operationally closed in an absolute way because each system is constantly traversed by an order of speech that determines what can and cannot be legitimated as knowledge. This order is not only contingent but is structured by power relations that determine which propositions are accepted because they are “in the true” (Foucault 2010, p. 224) and which are excluded. In a Foucauldian approach, the self-referentiality of a system such as the scientific system is ultimately an illusion because all knowledge is produced in a field of forces that includes political, economic, and cultural tensions that shape its historical conditions of possibility. Scientific practices cannot be separated from the social and political practices that allow them to operate.

In addition, Foucault pays particular attention to the discontinuities between different epochs, that is, the moments when forms of knowledge power are radically restructured by changes in discursive practices and their relationship to non-discursive practices. The production of knowledge is always traversed by practices of power and resistance, which cannot be explained solely by self-referential mechanisms that are purely internal to the systems.

In the specific case of theological knowledge, a fundamental problem in the structural coupling with modern universities lies in the divergence between two regimes of rationality: while the scientific system that governs the university is guided by a public rationality, contemporary theology remains largely referenced by a confessional rationality based on Revelation. This emphasis on Revelation as the ultimate criterion of truth can be interpreted as a symptom of the historical conditions of possibility that have shaped the place of the religious system in modern societies and partly explain its current epistemological marginality. Yet, historically, theology emerged as a public discourse intertwined with philosophy and public reason. The reduction of theology to fundamental theologies centered on Revelation reinforces epistemic self-enclosure, despite efforts to reinterpret Revelation in dialogue with modern experience (Rahner 1941, 1984; Ratzinger 1969; Latourelle 1966; Gutiérrez 1971; Libanio 1992; Tillich 1951–1963; Pannenberg 1961; Geffré 1972; O’Collins 2016; Theobald 2001, among others).

In their joint work Offenbarung und Überlieferung (Rahner and Ratzinger 1965), Karl Rahner and Joseph Ratzinger engage in a profound theological dialogue on the relationship between Revelation and Tradition, which is necessarily mediated not only by ecclesial forms but also through historical ones. Despite their differences, both authors converged in their understanding that Revelation is not merely a repository of fixed truths but a dynamic event that unfolds through the life of the believing community. This conception of a historically mediated and dialogical process anticipates the key issues later explored in Dei Verbum (Pope Paul VI 1965), offering a valuable foundation for modern reflections on public theology, particularly concerning the relationship between faith, reason, and historical consciousness. It is precisely this dynamism that positions 21st-century theology within contemporary universities, where it faces the epistemological challenge of achieving recognition not just through concordats, but throughout the scientific community. Theology must be translated into the language of public rationality to contribute to citizenship and the common good without abandoning its confessional roots (Tracy 1996). However, it does demand a rigorous translation and a broadening of its epistemological understanding so that it can fit better in the mission of modern universities to promote the formation of citizens’ critical conscience and contribute to the common good.

In contrast to the logic of self-referentiality, Francis used the metaphor of the polyhedron to describe theology as polyphonic—open to diversity yet united in dialogue and oriented to the common good (Pope Francis 2017, n. 3). Foucault similarly speaks of a “polyhedron of intelligibility,” where knowledge is structured by multiple, irreducible relations. The analysis of a field of knowledge requires taking into account the multiplicity of relations that make it up, forming a polyhedron whose faces are not given in advance and whose complexity cannot be completely reduced to a single point of view (Foucault 2001, p. 227).

On the same horizon, Michel de Certeau—identified by Pope Francis as a major influence (La Civiltà Cattolica 2013; IHU On-Line 2013)—proposed to think about an “archaeology of the religious” (archéologie religieuse) in which the religious element functions as a matrix of intelligibility. In L’écriture de l’histoire, he argued that modern historiography does not entirely break with the religious but rather reinscribes the experience of alterity and absence—God, the Other—into secular modes of knowledge (Certeau 1975, p. 121).

The task of an archaeology of theological knowledge thus acquires a critical and plural character. It involves reflecting on theology’s entanglement with knowledge, society, and power; identifying the multiple genealogies that shape its discourse; and overcoming epistemic self-referentiality to contribute to a public theology in dialogue with contemporary rationality—particularly as it emerges within the human sciences. As such, this article does not seek to deny the legitimacy of self-referential epistemological modes of dogmatic theology as a belief system. Instead, it highlights the epistemological risks of isolating theological discourse from broader societal dialogue, particularly when theology becomes a university discipline within a scientific system through concordats rather than epistemic consensus among various fields of knowledge, as was typical with the emergence of the human sciences. In this context, public theology is presented as an additional approach that allows theology to engage with the public sphere through epistemological openness and interdisciplinary interactions.

In this way, the archaeo-genealogical toolbox is employed here to illuminate the historical and relational conditions underlying the emergence of public theology through three complementary dimensions: (1) the archaeology of knowledge, (2) the genealogy of power apparatuses, and (3) the genealogy of ethics or processes of subjectivation—each contributing to the analysis of theology’s epistemic displacement.

3.1. The Trajectory of Michel Foucault’s Archaeological Method

In order to outline an archaeology of theological knowledge, it is first necessary to understand some aspects of the first moment of Foucault’s analyses, corresponding to the trajectory of the archaeological method, and its relation to the second moment of his thought, when the refined elaboration of the genealogical method takes place.

In a broad sense, the archaeological analysis does not aim to search for an origin or a history of ideas but rather to systematically describe the birth of a discourse-object based on enunciative regularities between different types of knowledge in the same long period of time, which come to share an enunciative homogeneity, forming a kind of bundle of discursive relations. To understand this point of arrival for the archaeology of knowledge, it is helpful to elucidate its trajectory.

Foucault’s archaeological project in the 1960s is exemplified by History of Madness (Foucault 1961), where he explores how different periods constructed the perception of madness as a cultural and institutional phenomenon. In The Birth of the Clinic (Foucault [1973] 2003), he extends this analysis to medical discourse, showing how the shift from metaphysical to empirical observation in the late 18th century transformed clinical practice. This transition—from symptom to lesion, from theory to anatomical gaze—illustrates how knowledge is shaped by institutional practices. Ultimately, Foucault links this evolution to the emergence of biopower and the modern control of bodies through medical authority.

Finally, his last archaeological exercise, known as Opus Magnum, led to the publication of Les mots et les choses (literally words and things)3, whose subtitle also indicates the object of its excavation, namely An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (Foucault 1966). The book deals with the discursive formation that led to the emergence of this field of knowledge in the nineteenth century, which, according to the French philosopher, consisted mainly of the social sciences, psychology, and literature—from the opening to positivity of the finitude of the human being not only as a transcendental subject in Kantian philosophy but above all as an empirical object, making it possible to grasp him not only as the subject of his reflection but also as his own object. It is here that Foucault analyzes the formation of knowledge and its historical conditions of existence and the way in which discourses articulate words and things in modernity, no longer governed by the notion that words merely reveal and represent the already given meaning of things.

It is only in this 1966 book that the centrality of knowledge is acknowledged, through the intersection of its philosophical and empirical perspectives, between which a synchronic continuity is identified (for example, in the perspective of finitude that runs through biology, political economy, and philology in modernity) and a diachronic discontinuity (the reconfiguration of the relationship between words and things in the sphere of knowledge based on the change in the archaeological network in which they are found). The archaeology of knowledge in Les mots et les choses aims to identify the limits of what is thinkable in a given culture—in this case, Western European culture. To do this, Foucault turns to literature to show the extent to which an order of knowledge that does not belong to our cultural codes of apprehension provides an almost complete alienation. And yet these codes, which are completely different from those of their own, have a way of being understood in the archaeological soil in which they were built.

Foucault’s decision to pursue the archaeology of the human sciences was inspired by Borges’ fictional taxonomy, which revealed the self-referential nature of Western categories of thought. It refers to an entry on animals in a “certain Chinese encyclopaedia”:

‘animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies’.(Foucault 2008, Preface, p. XVI)

The philosopher commented on the impression the poem made on him when he realized that Western thought was in danger of thinking variations on the same thing. As said by the French philosopher:

“In the wonderment of this taxonomy, the thing we apprehend in one great leap, the thing that, by means of the fable, is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own, the stark impossibility of thinking that.”(Foucault 2008, Preface, p. XVI)

In this way, the archaeological task can be seen as a way of forming a theoretical toolbox to identify forms of self-referentiality.

Furthermore, in the preface to The Order of Things, Foucault makes it clear that his aim is not to tell a chronological history of the human sciences but to reveal the networks of thought that have shaped knowledge in different periods. He defines this as ‘archaeology’, as he digs beneath historical surfaces to find the underlying rules that organize discourses and forms of knowledge that are taken for granted by the subjects of the time. In this way, the French philosopher aims to identify the rules of speech that organize and legitimize what can be said and thought as scientific in a given period.

Michel Foucault’s archaeological task, then, was to progressively understand and describe what he called the episteme, that is, the set of historical rules that, at a given time, establish the conditions of possibility for a field of scientific knowledge, leading to the emergence of the so-called ‘human sciences’. The episteme is not simply a body of knowledge or a set of ideas; it is the invisible and underlying structure that determines what can be known, thought, and said at a given time, even before knowledge is organized into specific disciplines. Episteme can be understood as “a priori is what, in a given period, delimits in the totality of experience a field of knowledge, defines the mode of being of the objects that appear in that field” (Foucault 2005b, p. 158).

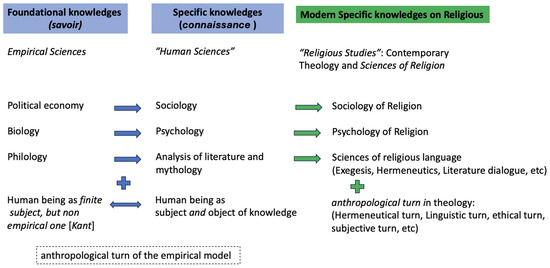

The archaeological method is based on the rules or historical a priori that define what knowledge is for each era. It is a ‘network of knowledge’ that connects all areas of knowledge and influences the forms of truth that are accepted in a period. The episteme is not conscious, but it is the background that shapes the knowledge of an era, allowing certain concepts to make sense while others do not. Each specific piece of knowledge (savoir) needs to relate to this network of foundational knowledge (connaissance).

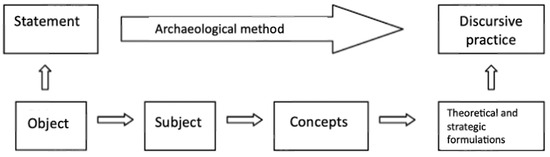

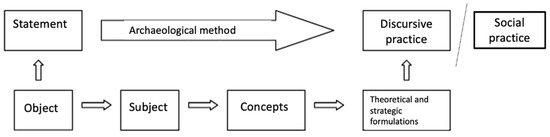

In The Archaeology of Knowledge (Foucault 1969), Foucault outlines a method for analyzing the historical conditions that make knowledge possible in different periods. Rather than seeking the origin of ideas or the intentions of authors, archaeology focuses on analyzing the discursive practices and regularities that govern the constitution of knowledge. This archaeology is structured around four elements—object, subject, concepts, and strategies—understood not as fixed entities but as relational functions within a discursive field. These are articulated through the statement (énoncé), the method’s basic unit, not a sentence but a discursive function that enables something to be said meaningfully within specific institutional and historical conditions. A statement does not exist in isolation: it is situated within a set of rules that determine who can speak (subject), what may be spoken about (object), with which conceptual tools (concepts), and under what strategic conditions or power relations (strategic formulations). The statement is the intersection of these four dimensions, allowing discourse to emerge meaningfully within a given historical configuration (see Figure 1). The archaeologist’s task is to describe this field of statements and to uncover the rules that govern their formation, transformation, and exclusion.

Figure 1.

Archaeological method Diagram adapted by the authors based on the methodological structure described by Gonçalves (2009).4

The object emerges within a statement, shaped by the discursive practices that define its properties and modes of existence. The subject is likewise positioned by the statement; there is no subject prior to it, only subject positions determined by what may be said. Concepts are mobilized and structured through statements, defining fields of reference, intelligibility, and regimes of truth. Finally, strategies determine the effects of statements, assigning them a role within a field of knowledge power and situating them in ongoing struggles and relations of force.

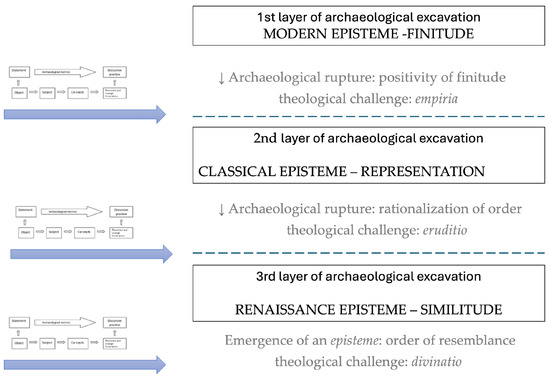

The French philosopher emphasizes discontinuities and ruptures that allow new rules for the emergence of a new understanding of what scientific knowledge is, at least in three periods. These epistemic configurations do not follow a linear progression but rather mark historical thresholds that redefine the historical conditions of possibility of knowing. Although Foucault did not analyze theology, the emergence of a new configuration in this set of rules obviously has repercussions for theology by changing the scenario of knowledge production in an era: (1) From Antiquity to the Renaissance, knowledge was organized around the principle of resemblance. Words aimed to reflect the relationships between things, understood as signs inscribed in a cosmos that could be deciphered. This way of knowing can also be associated with the ancient divination (Foucault 2005b, pp. 36–37, 65–66), a contemplative and symbolic mode that presupposes a world animated by divine traces, where meaning is revealed through analogies, correspondences, and signatures, in which nature is in the form of being deciphered by the human being, a mode of knowledge oriented toward the perception of beauty (thaumazein) in the order of things. It was the first theological challenge of transposing the narrative theology of the Semitic tradition into the rules of knowledge production elaborated by the ancient Greeks. Without this transposition, dialogue with the Greco-Roman world would not have been possible. (2) The Classical period (17th century until the transition to the 19th century), as named by Foucault and influenced mainly by Descartes, marks a rupture in which thought separated words from things in order to create a rational, unchanging order of representation. Language became a transparent medium to structure and classify reality. This period directly influences the second scholasticism, both Catholic and Protestant, in which one can identify a shift in the way the figure of God is associated with the rules of knowledge production. In this sense, God ceases to be analyzed through things and begins to inhabit the world of scholastic eruditio (Foucault 2005b, p. 37) characterized by a systematic and taxonomic approach to knowledge, a rationality in which erudition places the idea of God in an exercise of abstraction that aspires to universality and epistemic clarity. (3) In the Modern period, which replaces the classical episteme, knowledge is primarily structured by the emergence of finitude as a historical and epistemological condition. According to Foucault, this marks a radical shift: the archaeology of knowledge breaks with the philosophical narrative that interprets the birth of the human sciences as a progressive unfolding of the idea of human nature. Instead, the modern episteme is grounded in history itself, whereby the finitude of human nature is no longer seen negatively in contrast to the perfection of the divine infinite but rather becomes the central positive datum around which knowledge is organized. This regime is defined by the constitution of “man” as both subject and object of knowledge—a figure that arises not from the metaphysical continuity of the Enlightenment but from a series of discontinuous discourses: philosophical (notably in Kant) and empirical (philology, political economy, biology). In this configuration, empirical methods do not merely provide observational tools: they articulate the historicity and limits of human knowing. This period thus corresponds to the emergence of the modern ‘man’ as an empirical–transcendental figure, essential for the notion of finitude (Foucault 2005b, p. 357s). Thus, for scholastic theology, modernitas meant empiria, a challenge to think of the theological tradition beyond metaphysical eruditio about life, but from an analysis of finitude and its basic dimension of empiricism situated in the concrete conditions of human life, as a way of engaging with the positivity of finitude, the most decisive event in the modern order of knowledge (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Archaeological excavation layers.

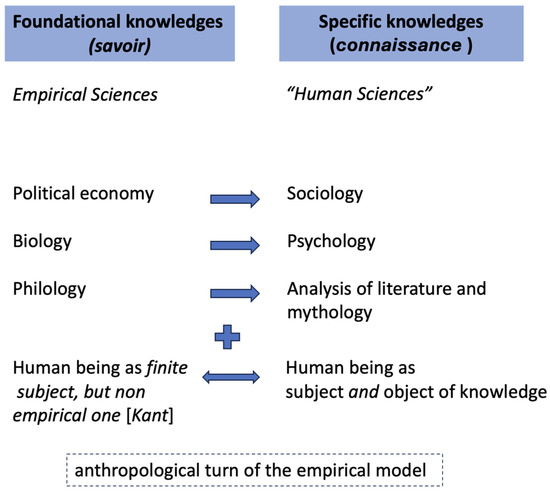

In this sense, the human sciences simultaneously become a specific knowledge in harmony with the set of foundational knowledges that shape the meaning of modern science. It means human sciences are scientific knowledge from their connection with the empirical basis of thought.

In other words, the human sciences emerged from the insufficient use of language from metaphysics in translating the empirical model to a cultural perspective. They were responsible for shaping the subjectivity of the modern individual. Human sciences emerged as an anthropological turn in empirical knowledge, transforming the human being not only into an object but also into a subject of their own knowledge.

If, at the empirical level, it is political economy (labor), biology (life), and philology (language) that discover finitude in a more radical manner, at the philosophical level, it is Kant’s philosophy that opens the way to a “finite subject” (Figure 3). In fact, Kant creates a transcendental field in which the finite subject (because it is deprived of the intellectual intuition of metaphysics), but which is not empirical (because it is not given in experience, as in the empirical sciences), determines in its relation to any objects the formal conditions of experience in general (Foucault 2010, p. 264) and thus carries out a synthesis between representations. In contrast, and without paying attention to this Kantian distinction between the empirical and the transcendental subject, modern philosophy—especially positivism, dialectics, and phenomenology—sought to identify in the empirical subject of the sciences of life, work, and language the transcendental conditions of experience, thus inaugurating modern anthropologism through the ‘confusion’ between the empirical and the transcendental. Modern man is thus, from his very origins, both an empirical and transcendental object of knowledge (as one who works, lives, and speaks) and, at the same time, a condition of the possibility of this knowledge (as a transcendental subject whose finite categories of space and time make it possible to grasp the object, first through sensibility and then through the intellect, thus effecting a synthesis between representations). The human sciences are thus characterized as an anthropological turn of the empirical model of knowledge as an analytic of finitude.

Figure 3.

The formation of human sciences.

3.1.1. The Relation Between Archaeological and Genealogical Methods

The genealogical method introduced by Michel Foucault deepens rather than ruptures his analysis of the historical conditions of knowledge and its entanglement with power, already evident in his 1970 inaugural lecture at the Collège de France, published as The Order of Discourse (Foucault 1971). As Domingues (2023, p. 347) observes, the analytics of power was already implicit in the archaeological phase, as the emergence and legitimation of knowledge depend on external—especially political—conditions. Genealogy builds on this by tracing how truth is historically produced through such entanglements.

Foucault himself clarified this in 1984, distinguishing archaeology’s concern with rules of formation from genealogy’s focus on intersecting and transforming discursive practices:

“The analysis I was proposing was archaeological insofar as it was not intended to capture what was hidden, but to bring to light the play of rules that determine the appearance of statements as singular events. But it was also genealogical, in that it was not concerned with reconstituting formal successions, but with detecting discursive formations as multiple practices that intersect, repeat, transform, and sustain one another” [free translation].(Foucault 1984, p. 14)

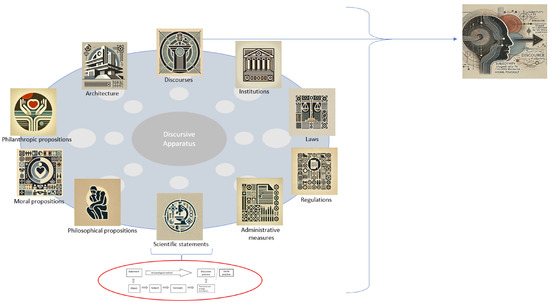

What was previously centered on the conditions of possibility for statements and discursive formations now also incorporates the relations of force that traverse and historically constitute those formations. Foucault’s metaphor of the ‘polyhedron of intelligibility’ illustrates this multidimensional character of knowledge power formations. The polyhedron, with its multiple, open-ended facets, illustrates the multiplicity of relations that compose any historical formation of knowledge power. For Foucault, understanding a historical event or process does not involve recovering its unique origin or a linear cause but tracing the multiple lines of force, knowledge, and practices that intersect in its constitution (Foucault 1994, p. 24). This relates to the concept of apparatus (dispositif), a network of discourses, institutions, norms, practices, and strategies that operate as mechanisms of power and knowledge in a society.

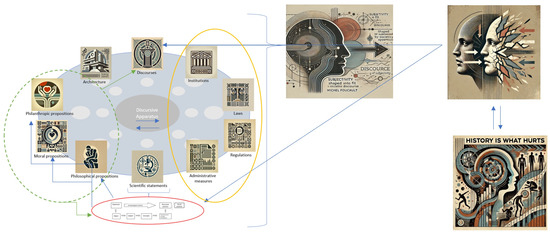

The genealogical method, which succeeds and complements archaeology, seeks to describe the emergence and transformation of these apparatuses, revealing how they organize conduct and produce subjectivities. While the archaeological method analyzes the historical conditions of possibility for statements and knowledge within a discursive formation, genealogy investigates the correlations of force and strategies of power that sustain and modify such formations across knowledge fields. The polyhedron of intelligibility is thus a powerful image (Figure 4) of this complex and dynamic analysis, one that resists reduction to a homogeneous totality and remains open to the multiple genealogies and apparatuses that shape regimes of truth and social practices.

Figure 4.

The metaphor of the polyhedron applied to the apparatus.

In the late 1970s, Foucault introduced the concept of governmentality (gouvernamentalité) to analyze the emergence of modern political rationalities. Foucault aimed to analyze how the state became “governmental,” that is, how a rationality for governing others and oneself emerged (Candiotto 2008, p. 90). This shift is traced from medieval advice to princes literature to early modern Stoicism, where spiritual counsel gave way to the arts of government (Foucault 2008, p. 281). This governmental rationality, however, does not emerge ex nihilo. Foucault identifies its deeper roots in Christian traditions of pastoral care, where governing individuals’ conduct—spiritually and morally—prefigures modern techniques of population management. This continuity becomes visible in his genealogy of pastoral power. This situation gave rise to a deep concern over “how one wishes to be spiritually guided on this earth toward salvation”—a transcendent issue that was, however, intimately tied to the immanent order of a Christianized society. In the sixteenth century, this became a structurally sensitive problem, as it threatened the cultural–religious unity that had sustained the social body. This tension encompassed a range of political questions inherently linked to the spiritual one: “how to be governed, by whom, to what extent, to what ends, and by what means?” (Foucault 2006, p. 282).

Foucault’s genealogy of pastoral power shows how Christian techniques of spiritual direction evolved into modern technologies for governing populations, emphasizing the production of truth and the constitution of subjectivities. This transformation is rooted in the emergence of centralized states and the religious upheavals of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, which reshaped the political and spiritual question of how people are to be governed—by whom, to what end, and with what means (Foucault 2006, p. 282). Rather than recovering the Stoic ideal of government as self-mastery, Foucault traces a distinctly Christian model of pastoral government: a form of power exercised by the clergy over a mobile flock, formalized after the Council of Trent through the creation of seminaries (Foucault 2008, p. 224).

Unlike Greek and Stoic traditions, where leadership was tied to territory and self-governance, and unlike Judaism, where God alone is shepherd of his people (Foucault 2006, pp. 358–59), Christian pastoralism implies guiding individuals toward salvation through structured obedience and confession (Foucault 2008, p. 168). Two central mechanisms define this model: total obedience—requiring the renunciation of personal will—and exhaustive confession, aimed at extracting inner truths (Foucault 2008, p. 196). These mechanisms converge in the practice of spiritual direction, in which truth is produced through verbalized self-examination under the interpretative authority of a director. This dual regime of truth—Revelation and confession—is institutionalized under surveillance (Foucault 2008, p. 8), producing subjects through subjection to knowledge they come to recognize as their own (Candiotto 2010, p. 85).

Foucault contrasts this with Stoic spiritual direction, where obedience is temporary and geared toward autonomy through alignment with logos, without requiring inner confession. In Christianity, however, obedience becomes an end in itself, embedded in a permanent asymmetry of power. He locates the origins of this model in the fourth century, particularly in the thought of John Cassian, who formulated the principles of endless obedience, unceasing examination, and exhaustive confession (Foucault 2018a, p. 262). Cassian urged disciples to “disclose [their thoughts] to their elder as soon as they arise […] and not rely on their own discernment” (João Cassiano 2004, Institutes, IV.9). Foucault identifies this nexus of truth production and self-renunciation as the “schema of Christian subjectivity” (Foucault 2018a, p. 280), later systematized in the Borromean model of spiritual direction, where the director becomes a “guardian angel” entrusted with the inner life of the penitent (Foucault 2001, p. 232).

3.1.2. The Relation Between the Archaeology of Knowledge and the Genealogy of Ethics

This historical configuration of subjectivity, grounded in the interplay between confession, obedience, and surveillance, prepares the ground for Foucault’s subsequent inquiry into the ethical dimension of subject formation—namely, the relation between the archaeology of knowledge and the genealogy of ethics.

Building upon the relation between knowledge, power, and subjectivation explored in the genealogical analysis of pastoral power, Foucault turns toward the ethical dimension of subject formation through the concept of spirituality.

Far from being limited to a religious or mystical dimension, spirituality in its Foucauldian sense refers to concrete practices of self-transformation that enable the subject to access truth and resist historical forms of subjection. This perspective inaugurates a mode of analysis in which care of the self—drawn from ancient philosophical traditions—is reinterpreted as a field of articulation between knowledge, power, and subjectivation. It is at this intersection that spirituality and genealogy converge: both seek to understand how the ethical constitution of subjects is inscribed within the meshes of power, and how it can simultaneously open breaches of freedom and the creation of new forms of existence.

This new interest is also tied to his diagnosis of the “decline of revolutionary desire in the West” (Candiotto 2020, pp. 111–12). This concern led him to reflect on the “religious origins of modern revolutions,” especially after reading The Principle of Hope by Ernst Bloch and analyzing the Iranian Insurrection of 1978. This event struck Foucault because it articulated a political agenda for social transformation with a strong spiritual dimension—without mediation by the traditional forms of Western Marxism.

Foucault identified in this phenomenon what he called political spirituality, understood as a practice of resistance and self-transformation through which the subject breaks with the subjection imposed by power apparatuses and constitutes itself as a subject of knowledge, belief, and action. It is a process of renouncing the condition of the dominated and enacting subjective insurrection: “To become other than what one is, other than oneself” (Foucault 2006, p. 21).

Rather than a form of traditional militancy, political spirituality constitutes an interior practice of freedom through which the subject breaks social and political subjection.

Later, Foucault developed the notion of spirituality as care of the self in his lecture course L’Herméneutique du sujet (1981–1982). Here, he broadens the concept: spirituality is no longer merely a political force of resistance but a set of individual ethical practices by which the subject transforms itself in order to access truth. For Foucault, spirituality refers to the set of transformative practices that constitute the subject as a necessary condition for the apprehension of truth (Foucault 2005a, p. 19).

This epimeleia heautou is not a nostalgic return to ancient ethics but a secularized form of spirituality, which is expressed in contemporary practices of resistance. Drawing on Greco-Roman traditions of self-transformation—such as Stoic and Epicurean exercises—Foucault demonstrates that access to truth requires an inner metamorphosis of the subject. It is through this trajectory that he elaborates a genealogy of ethics, shifting his focus from epistemology to practices of subjectivation. Here, care of the self becomes a practice of freedom, a mode of constituting the self through resistance. As he puts it, the genealogy of ethics involves “an ethical work on the self” (Foucault 2006, p. 49), in which truth emerges not as a given but as the effect of a new mode of being.

Thus, political spirituality, care of the self, and the genealogy of ethics become interconnected: resistance to subjection, inner transformation, and the constitution of free subjects are three dimensions of the same movement of freedom production. As Foucault notes, “all the great political, social and cultural upheavals could only effectively take place in history from a movement that was a movement of spirituality” (Foucault 2018c, p. 23). Therefore, the genealogy of ethics reveals the inseparability of self-transformation and world transformation.

Spirituality as care of the self may serve as the basis for a political practice that does not aim merely to reform external structures but to reshape subjectivity itself in critical relation to historical forms of power.

Given the complex and intrinsic relationship between knowledge and power, when there is an abuse of power, it calls for a genealogy of ethics—as a way of subverting knowledge and inverting power into a force of resistance. This is especially relevant when subjectivity is challenged by what wounds it historically—by the painful nature of historical processes.

To illustrate this complex dynamic, knowledge, like a river, carries evolving ideas and theories. Power, like riverbanks, shapes and channels this flow. Over time, however, knowledge erodes and reshapes power, creating new paths and possibilities. This illustrates how knowledge influences and redefines power, generating new truths that guide and transform action when rooted in a genealogy of ethics. Subjectivity arises both from adherence to norms and from the potential for resistance when faced with abuse, making it a dynamic and historical process. In other words, knowledge continually reshapes the structures that once confined it, producing new regimes of truth that reconfigure power.

This new mode of knowledge can emerge either through a spirituality conceived as a renewed consciousness that comes from caring of the self, where ethical transformation enables access to truth, or as a form of political spirituality inscribed in a collective agenda of resistance and social reconfiguration; both trajectories constitute distinct yet convergent expressions of a genealogy of ethics, in which subjectivation becomes the site of epistemic and political innovation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The metaphor of the polyhedron applied to the genealogy of ethics.

It is precisely within this relationship—between spiritual transformation and genealogical critique—that the production of theological knowledge takes place, always conceived as the second act of a first existential or spiritual experience. In dialogue with Foucault’s archaeological project, Michel de Certeau identifies spirituality as a kind of Trojan horse inserted into theological discourse: it destabilizes doctrinal closures from within and exposes their entanglement with structures of abusive power. This becomes especially urgent in the face of history’s wounds—those open traumas that, through institutional negligence or as by-products of power apparatuses, infiltrate the daily lives of individuals and communities.

3.2. The Archaeology of the Religious and the ‘Genealogy’ of Ethics in Michel de Certeau

In Heterologies, Michel de Certeau describes Michel Foucault’s archaeology as driven by a paradoxical experience of absence and fascination with what he calls ‘the black sun of language’ (Certeau 1986, p. 171). This image refers to a blind spot, an opaque source of light that both generates and obscures meaning, a place where language is revealed in its radical otherness but also in its essential opacity.

For Certeau, this ‘black sun’ expresses the condition of Foucault’s archaeological project: a language that excavates the rules of knowledge formation but finds no ultimate foundation, only a field of games, ruptures, and silences. It is a knowledge that operates without a founding subject, without a transcendental origin, but which is paradoxically structured around this central absence. Foucault, according to Certeau, becomes the ‘historian of disappearance’ because he explores the negativity at the heart of Western knowledge, exposes the flaws in the fabric of speech, and illuminates an absence—the death of God, the death of man, the eclipse of full meaning—that underlies modernity (Certeau 1986, pp. 171–72).

This notion has direct implications for the unfinished task of an archaeology of the religious, which would allow a theology of difference to overcome its self-referentiality. The black sun suggests that all theological language is pervaded by an original emptiness, an irreducible otherness that prevents any systematic or totalizing closure. The theology of difference inspired by this vision does not seek to fill the void with new dogmatic syntheses but to inhabit the gap and to welcome the otherness of God and the other as sources of meaning that escape attempts at totalization.

By emphasizing the black sun as an image of Foucault’s archaeological language, Certeau invites theology to recognize that its own language is always in danger, always on the threshold between word and silence, between Revelation and absence. The Mystic Fable that Certeau explores in his later work is an expression of this tension: speech that is aware of its own inadequacy and yet continues to narrate, to invoke, and to translate the ineffable (Certeau 1995, p. 109).

Certeau thus shows how modern history does not completely break with the religious model; it transforms the religious experience of otherness and absence (God, the other) into a historiographical practice that deals with the past as an absent other. For Certeau, the historian becomes the one who replaces the theologian: someone who deals with traces and remnants and, on the basis of them, writes a narrative with an ordering and normative function. His proposal for an archaeology of the religious thus has a critical function: it makes visible this return of the repressed, that is, the persistence of an underlying theological structure in the way historical knowledge is narrated and organized.

Certeau emphasizes the question of otherness, which, as it is known, is virtually absent from Foucault. He is interested in the experience of those who write history, in the relationship between enunciation and absence, and in the symbolic processes inherited from religion, especially how the symbolic processes of recognizing otherness affect social practices despite the discursive practices of normative theology. History is a field for excavating the traces of otherness that are absent from historiography, with social practices being a privileged site for this absent presence of otherness that is repressed from the point of view of discursive practice.

Michel de Certeau does not present a systematic concept of ‘genealogy’ along Foucauldian lines but offers contributions that allow a genealogical reading of his historiographical method (Certeau 1975, pp. 14, 107–8, 314). In several passages, Certeau focuses on the historical shifts in ethics, religion, and knowledge, showing how discursive and institutional practices emerge, transform, or are marginalized over time. However, the French Jesuit points to the establishment of an epistemological incompatibility between theology and the emerging human sciences in the 19th century, since the latter operated with an ethical primacy of speech, while theology remained with a dogmatic primacy, which hindered dialogue and led to the distancing.

Rather than a formal theory, Certeau address a genealogy of ethics as a shifting field of meaning in which ethical discourse emerges not from doctrine but from situated, embodied practices that function as interpretative operators of modern social life. From the 17th century onwards, Christian ethics was confronted with social and political critiques that displaced it from its normative position and replaced it with a dialectic of uses and conflicts of power, especially with regard to the control of religious behavior. Between the 17th and 18th centuries, a rupture between religion and morality was consolidated, allowing the emergence of an autonomous social ethics responsible for organizing collective practices and relativizing inherited belief systems. This autonomy culminated in the Enlightenment with the primacy of ethics over faith, strongly influenced by Rousseau, who privileged morality over dogma. In the 18th century, ethics became associated with the ideal of progress and democratization, taking on the role of guiding the improvement of societies. Religious practices were reinterpreted in terms of a new social order in which ethics determined behavior and replaced the old religious frameworks. In this context, Christian ethics was absorbed and reorganized by the logic of the ‘duty of the state’, which linked moral meaning to the social position held and the functions performed. This reorganization also led to a split between piety and morality: morality became a public language, while piety was relegated to the private sphere. Popular culture, in turn, is reinterpreted as an instrument of public utility, incorporating religious and social practices into the ethical language of modernity. In The Writing of History, Certeau presents a certain ‘genealogy’ of ethics in which it becomes a pragmatic linguistic device in which ethical speeches organize social meanings, legitimacies, and ways of life. It is a practical, situated, and historical ethics that functions as a key to understanding human behavior within the concrete conditions of modern society. In place of obedience to dogma, an ethics emerges as a language of practice, articulated with the apparatuses of the state, with discourses of progress, and with mechanisms of control and self-formation. This ethics replaces dogma as the epistemic axis of the human sciences and functions as a criterion of intelligibility for modern experience (Certeau 1975, p. 19, 152f).

The place of theology seems to have been left empty by the human sciences. Theology is seen as an institution for the enunciation of meaning that remains tied to a dogmatic order, a semantics that is identified either with ideology or with private convictions that are incompatible with scientific analysis. The so-called human sciences, on the other hand, are developing into forms of knowledge whose project and method, based on statutes, social tasks, and conflicts, reorganize the meaning of existence. The primacy of ethics for Certeau is not a kind of principle of moral superiority but rather an operative capacity to produce meaning from everyday life. This primacy relegates theology to a marginal or reactive position, requiring it to reconcile itself with the devices of meaning production inherent in modernity.