Spirituality and Religiosity—Do They Always Go Hand in Hand? The Role of Spiritual Transcendence in Predicting Centrality of Religiosity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Spirituality

1.2. Religiosity

1.3. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.2. Sex Differences

3.3. Measurement Invariance

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, Rolf. 2022. Gender and Survey Participation: An Event History Analysis of the Gender Effects of Survey Participation in a Probability-Based Multi-Wave Panel Study with a Sequential Mixed-Mode Design. Methods, Data, Analyses 16: 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, Anton A. 2014. Psychologie der Spiritualität [The Psychology of Spirituality], 2nd ed. Beltz: Weinheim. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, Arndt, Thomas Ostermann, and Peter F. Matthiessen. 2005. Role of Religion and Spirituality in Medical Patients: Confirmatory Results with the SpREUK Questionnaire. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 3: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Carey, Jeremiah. 2018. Spiritual, but Not Religious?: On the Nature of Spirituality and Its Relation to Religion. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 83: 261–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Fang Fang. 2007. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling 14: 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Paul T., and Robert R. McCrae. 1992. The five-Factor Model of Personality and Its Relevance to Personality Disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders 6: 343–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmrich, Sarah, and Stefan Huber. 2019. Multidimensionality of Spirituality: A Qualitative Study among Secular Individuals. Religions 10: 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Robert A., and Raymond F. Paloutzian. 2003. The Psychology of Religion. Annual Review of Psychology 54: 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genia, Vicky. 1997. The Spiritual experience index: Revision and reformulation. Review of Religious Research 38: 344–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, Charles Y. 1962. On the Study of Religious Commitment. Religious Education 57: 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2022. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Peter C., Kenneth I. Pargament, Ralph W. Hood, Jr., Michael E. McCullough, Judith P. Swyers, and Bernard J. Zinbauer. 2000. Conceptualizing Religion and Spirituality: Points of Commonality, Points of Departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 30: 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan. 2003. Zentralität und Inhalt. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jach, Hayley K., and Luke D. Smillie. 2019. To Fear or Fly to the Unknown: Tolerance for Ambiguity and Big Five Personality Traits. Journal of Research in Personality 79: 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, George A. 1955. The Psychology of Personal Constructs. Vol. 1. A Theory of Personality. Vol. 2. Clinical Diagnosis and Psychotherapy. Oxford: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, Rex B. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2008. Concerns about Measuring ‘Spirituality’ in Research. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 196: 349–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, Neal M. 2008. Aging in the Church: How Social Relationships Affect Health. West Conshohocken: Templeton Foundation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lace, John W., Luke N. Evans, Zachary C. Merz, and Paul J. Handal. 2020. Five-Factor Model Personality Traits and Self-Classified Religiousness and Spirituality. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 1344–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Shanshan, Meir J. Stampfer, David R. Williams, and Tyler J. VanderWeele. 2016. Association of Religious Service Attendance With Mortality Among Women. JAMA Internal Medicine 176: 777–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Todd D., William A. Cunningham, Golan Shahar, and Keith F. Widaman. 2002. To Parcel or Not to Parcel: Exploring the Question, Weighing the Merits. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 9: 151–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, William R., and Carl E. Thoresen. 2003. Spirituality, Religion, and Health. American Psychologist 58: 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Jordan W., Adam E. Tratner, and Melissa M. McDonald. 2022. Men Are Less Religious in More Gender-Equal Countries. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 289: 20212474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, Paul S., David J. Plevak, and Teresa A. Rummans. 2001. Religious Involvement, Spirituality, and Medicine: Implications for Clinical Practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 76: 1225–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, Delroy L., Richard W. Robins, Kali H. Trzesniewski, and Jessica L. Tracy. 2004. Two Replicable Suppressor Situations in Personality Research. Multivariate Behavioral Research 39: 303–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piedmont, Ralph. 2005. The Role of personality in understanding religious and spiritual constructs. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 253–273. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont, Ralph L. 1999. Does Spirituality Represent the Sixth Factor of Personality? Spiritual Transcendence and the Five-Factor Model. Journal of Personality 67: 985–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedmont, Ralph L. 2001. Spiritual Transcendence and the Scientific Study of Spirituality. Journal of Rehabilitation 67: 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont, Ralph L. 2004. Spiritual Transcendence as a Predictor of Psychosocial Outcome From an Outpatient Substance Abuse Program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 18: 213–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piedmont, Ralph L. 2012. Overview and Development of a Trait-Based Measure of Numinous Constructs: The Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments (ASPIRES) Scale. In The Oxford Handbook of Psychology and Spirituality. Edited by Lisa J. Miller. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 104–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedmont, Ralph L. 2014. Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments (ASPIRES) Scale. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Edited by Alex C. Michalos. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 258–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedmont, Ralph L., and Jesse Fox. 2023. Hope and the numinous: Psychological concepts for promoting wellness in a medical context. Medical Research Archives 11: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedmont, Ralph L., and Marion E. Toscano. 2016. Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments (ASPIRES) Scale. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Edited by Virgil Zeigler-Hill and Todd K. Shackelford. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, Jarosław. 2018. Transcendencja Duchowa. Perspektywa Psychologiczna. Warszawa: Liberi Libri. [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski, Jarosław, Katarzyna Skrzypińska, and Magdalena Żemojtel-Piotrowska. 2013. Skala Transcendencji Duchowej. Konstrukcja i Walidacja. Roczniki Psychologiczne 16: 451–85. [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski, Christina, Betty Ferrell, Rose Virani, Shirley Otis-Green, Pamela Baird, Janet Bull, Harvey Chochinov, George Handzo, Holly Nelson-Becker, Maryjo Prince-Paul, and et al. 2009. Improving the Quality of Spiritual Care as a Dimension of Palliative Care: The Report of the Consensus Conference. Journal of Palliative Medicine 12: 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Yves. 2012. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 48: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydz, Elżbieta, and Anna Wieradzka-Pilarczyk. 2017. Religious Identity Status and Readiness for Interreligious Dialogue in Youth. Developmental Analysis. Journal for Perspectives of Economic Political and Social Integration 23: 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassilis, and Antonio Muñoz-García. 2008. Individual Differences in Religion and Spirituality: An Issue of Personality Traits and/or Values. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucier, Gerard, and Katarzyna Skrzypińska. 2006. Spiritual But Not Religious? Evidence for Two Independent Dispositions. Journal of Personality 74: 1257–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnell, Tatjana. 2012. Spirituality with and without Religion—Differential Relationships with Personality. Archiv Für Religionspsychologie/Archive for the Psychology of Religion 34: 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, Tatjana. 2020. Spirituality. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Edited by Virgil Zeigler-Hill and Todd K. Shackelford. Cham: Springer, pp. 5162–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaba, Ted, and Wiebke Bleidorn. 2018. Individual Differences in Personality Change across the Adult Life Span. Journal of Personality 86: 450–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, David B., Jody L. Newman, and Dale R. Fuqua. 2010. Further Evidence Regarding the Validity of the Quest Orientation. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 29: 334–42. [Google Scholar]

- Streib, Heinz, and Ralph W. Hood. 2011. ‘Spirituality’ as Privatized Experience-Oriented Religion: Empirical and Conceptual Perspectives. Implicit Religion 14: 433–53. Available online: https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2001069 (accessed on 3 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tart, Charles. 1975. Introduction. In Transpersonal Psychologies. Edited by Charles T. Tart. New York: Harper & Row, pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Yunping, and Fenggang Yang. 2018. Internal Diversity Among ‘Spiritual But Not Religious’ Adolescents in the United States: A Person-Centered Examination Using Latent Class Analysis. Review of Religious Research 60: 435–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, Tyler J., Shanshan Li, Alexander C. Tsai, and Ichiro Kawachi. 2016. Association Between Religious Service Attendance and Lower Suicide Rates Among US Women. JAMA Psychiatry 73: 845–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, Paul, Lucia Ciciolla, Michele Dillon, and Allison Tracy. 2007. Religiousness, spiritual seeking, and personality: Findings from a longitudinal study. Journal of Personality 75: 1051–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaden, David B., Cassondra L. Batz-Barbarich, Vincent Ng, Hoda Vaziri, Jessica N. Gladstone, James O. Pawelski, and Louis Tay. 2022. A Meta-Analysis of Religion/Spirituality and Life Satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies 23: 4147–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycka, Beata. 2007. Skala Centralności Religijności Stefana Hubera. Roczniki Psychologiczne 10: 133–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2005. Religiousness and spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, Brian J., Kenneth I. Pargament, and Allie B. Scott. 1999. The Emerging Meanings of Religiousness and Spirituality: Problems and Prospects. Journal of Personality 67: 889–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwingmann, Christian, Constantin Klein, and Arndt Büssing. 2011. Measuring Religiosity/Spirituality: Theoretical Differentiations and Categorization of Instruments. Religions 2: 345–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | Min. | Max. | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intellect | 343 | 3.00 | 15.00 | 7.27 | 2.94 | 0.49 | −0.393 | 0.85 |

| Ideology | 343 | 3.00 | 15.00 | 10.48 | 3.71 | −0.54 | −0.796 | 0.92 |

| Private practice | 343 | 3.00 | 15.00 | 8.78 | 3.85 | 0.001 | −1.254 | 0.94 |

| Experience | 343 | 3.00 | 15.00 | 7.48 | 3.25 | 0.34 | −0.59 | 0.93 |

| Public practice | 343 | 3.00 | 15.00 | 7.92 | 3.75 | 0.351 | −1.11 | 0.91 |

| Centrality (total score) | 343 | 15.00 | 75.00 | 41.93 | 15.57 | 0.019 | −0.93 | 0.96 |

| Transcendence proper | 343 | 11.00 | 44.00 | 27.89 | 8.14 | −0.169 | −0.78 | 0.92 |

| Spiritual openness | 343 | 16.00 | 44.00 | 34.66 | 5.66 | −0.659 | 0.27 | 0.84 |

| Spiritual transcendence (total score) | 343 | 28.00 | 88.00 | 62.54 | 12.39 | −0.35 | −0.32 | 0.92 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intellect | — | ||||||||

| 2. Ideology | 0.66 | — | |||||||

| 3. Private practice | 0.69 | 0.78 | — | ||||||

| 4. Experience | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.82 | — | |||||

| 5. Public practice | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 0.73 | — | ||||

| 6. Centrality (total score) | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.89 | — | |||

| 7. Transcendence proper | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.71 | — | ||

| 8. Spiritual openness | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.60 | — | |

| 9. Spiritual transcendence (total score) | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.93 | 0.85 | — |

| Variable | t | df | p | Mean Difference | SE Difference | Cohen’s d | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intellect | −0.72 | 340 | 0.47 | 0.31 | 0.43 | −0.11 | −1.16 | 0.53 |

| Ideology | −2.28 | 340 | 0.023 | 1.22 | 0.54 | −0.33 | −2.28 | −0.17 |

| Private practice | −2.52 | 340 | 0.012 | 1.4 | 0.56 | −0.37 | −2.5 | −0.31 |

| Experience | −2.61 | 340 | 0.009 | 1.23 | 0.47 | −0.38 | −2.15 | −0.3 |

| Public practice | −1.83 | 340 | 0.068 | 1.0 | 0.55 | −0.27 | −2.08 | 0.07 |

| Centrality (total score) | −2.29 | 340 | 0.023 | 5.17 | 2.26 | −0.33 | −9.61 | −0.73 |

| Transcendence proper | −3.51 | 340 | 0.001 | 4.09 | 1.17 | −0.51 | −6.38 | −1.79 |

| Spiritual openness | −1.75 | 340 | 0.081 | 1.44 | 0.82 | −0.26 | −3.06 | 0.18 |

| Spiritual transcendence (total score) | −3.11 | 340 | 0.002 | 5.53 | 1.78 | −0.45 | −9.03 | −2.03 |

| Model | Χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without age control | |||||||

| Configural | 800.56 | 336 | 0.936 | 0.09 | 0.046 | — | — |

| Metric | 812.69 | 350 | 0.936 | 0.088 | 0.048 | 0 | −0.002 |

| Scalar | 825.55 | 364 | 0.936 | 0.086 | 0.049 | 0 | −0.002 |

| Structural | 841.46 | 374 | 0.936 | 0.085 | 0.064 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| With age control | |||||||

| Configural (with age) | 875.09 | 368 | 0.931 | 0.09 | 0.056 | — | — |

| Metric (with age) | 887.39 | 382 | 0.931 | 0.088 | 0.057 | 0 | −0.002 |

| Scalar (with age) | 900.11 | 396 | 0.931 | 0.086 | 0.057 | 0 | −0.002 |

| Structural (with age) | 924.18 | 411 | 0.93 | 0.085 | 0.069 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

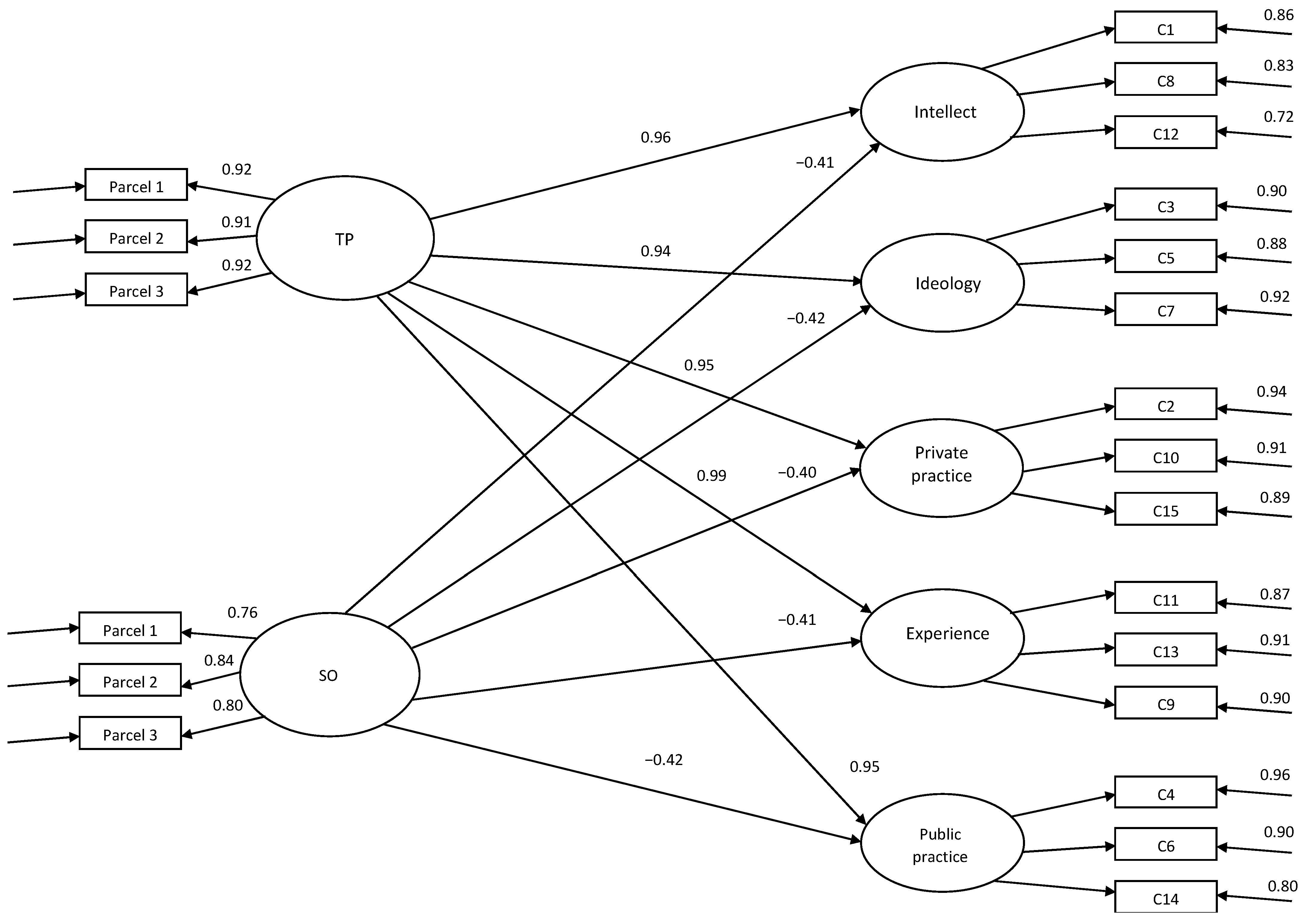

| Predictor | Outcome | β | SE | CR | p | 95% CI | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| TP | Intellect | 0.96 | 0.11 | 13.139 | <0.001 | 1.225 | 1.655 |

| SO | Intellect | −0.41 | 0.17 | −5.965 | <0.001 | −1.327 | −0.671 |

| TP | Ideology | 0.94 | 0.12 | 13.318 | <0.001 | 1.423 | 1.914 |

| SO | Ideology | −0.42 | 0.23 | −5.127 | <0.001 | −1.643 | −0.734 |

| TP | Private practice | 0.95 | 0.12 | 14.327 | <0.001 | 1.54 | 2.029 |

| SO | Private practice | −0.40 | 0.22 | −5.527 | <0.001 | −1.661 | −0.791 |

| TP | Experience | 0.99 | 0.1 | 14.607 | <0.001 | 1.23 | 1.612 |

| SO | Experience | −0.41 | 0.15 | −6.013 | <0.001 | −1.238 | −0.629 |

| TP | Public practice | 0.95 | 0.19 | 13.082 | <0.001 | 1.533 | 2.074 |

| SO | Public practice | −0.42 | 0.22 | −5.796 | <0.001 | −1.746 | −0.864 |

| Predictor | Outcome | β | SE | CR | p | 95% CI | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| TP | Intellect | 0.96 | 0.106 | 13.8 | < 0.001 | 1.25 | 1.67 |

| SO | Intellect | −0.41 | 0.162 | −6.19 | < 0.001 | −1.32 | −0.687 |

| Age | Intellect | 0.04 | 0.046 | 0.96 | 0.337 | −0.046 | 0.134 |

| Sex | Intellect | −0.09 | 0.146 | −1.81 | 0.071 | −0.549 | 0.022 |

| TP | Ideology | 0.93 | 0.13 | 12.7 | < 0.001 | 1.39 | 1.89 |

| SO | Ideology | −0.42 | 0.23 | −5.16 | < 0.001 | −1.64 | −0.736 |

| Age | Ideology | 0.05 | 0.052 | 1.23 | 0.217 | −0.038 | 0.168 |

| Sex | Ideology | 0.004 | 0.164 | 0.074 | 0.941 | −0.309 | 0.333 |

| TP | Private practice | 0.93 | 0.124 | 13.9 | < 0.001 | 1.48 | 1.97 |

| SO | Private practice | −0.40 | 0.217 | −5.57 | < 0.001 | −1.63 | −0.782 |

| Age | Private practice | 0.13 | 0.054 | 3 | 0.003 | 0.056 | 0.268 |

| Sex | Private practice | 0.02 | 0.141 | 0.463 | 0.644 | −0.211 | 0.341 |

| TP | Experience | 0.98 | 0.101 | 13.9 | < 0.001 | 1.21 | 1.6 |

| SO | Experience | −0.40 | 0.155 | −6.00 | < 0.001 | −1.23 | −0.625 |

| Age | Experience | 0.05 | 0.041 | 1.11 | 0.268 | −0.035 | 0.125 |

| Sex | Experience | 0.01 | 0.114 | 0.324 | 0.746 | −0.187 | 0.261 |

| TP | Public practice | 0.93 | 0.138 | 12.7 | < 0.001 | 1.48 | 2.02 |

| SO | Public practice | −0.42 | 0.221 | −5.83 | < 0.001 | −1.72 | −0.853 |

| Age | Public practice | 0.14 | 0.055 | 3.2 | 0.001 | 0.068 | 0.285 |

| Sex | Public practice | −0.009 | 0.145 | −0.222 | 0.824 | −0.316 | 0.251 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borawski, D.; Lipska, K.; Wajs, T. Spirituality and Religiosity—Do They Always Go Hand in Hand? The Role of Spiritual Transcendence in Predicting Centrality of Religiosity. Religions 2025, 16, 724. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060724

Borawski D, Lipska K, Wajs T. Spirituality and Religiosity—Do They Always Go Hand in Hand? The Role of Spiritual Transcendence in Predicting Centrality of Religiosity. Religions. 2025; 16(6):724. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060724

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorawski, Dominik, Katarzyna Lipska, and Tomasz Wajs. 2025. "Spirituality and Religiosity—Do They Always Go Hand in Hand? The Role of Spiritual Transcendence in Predicting Centrality of Religiosity" Religions 16, no. 6: 724. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060724

APA StyleBorawski, D., Lipska, K., & Wajs, T. (2025). Spirituality and Religiosity—Do They Always Go Hand in Hand? The Role of Spiritual Transcendence in Predicting Centrality of Religiosity. Religions, 16(6), 724. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16060724