1. Introduction: Becoming Divine in a World of Stories

Across the globe, anime fans gather around stories that, on the surface, appear fantastical, tragic, or heroic. Yet within these narratives drawn in ink, imagined in color, and carried across screens, many encounter something deeper: a presence, a question, a wound. They do not merely watch anime; they listen for echoes of a hidden or reimagined God. For some, anime becomes one of the last cultural spaces where the divine is not only remembered but is still becoming.

This article begins from a quiet yet radical hypothesis: that anime, as a narrative and aesthetic form, becomes a space where the sacred emerges as a story, as a process, as becoming, not as a static doctrine. Story itself is never still; it moves, breaks, heals, and transforms. When it stops unfolding, it collapses into mere description. But the sacred, like a story, is dynamic. It suffers, chooses, and grows. In this movement, divinity is not only revealed, it is created.

The present analysis focuses on five anime series that foreground theological and symbolic questions through fractured cosmologies and characters who approach the sacred through memory, sacrifice, care, and refusal: Puella Magi Madoka Magica, To Your Eternity, Sunday Without God, Code Geass, and The Promised Neverland. These works do not offer fixed images of God but invite the viewer into a journey of co-creation where divinity is found not above or beyond, but within the story itself. Characters such as Madoka, Mujika, Emma, and Ai function as feminine-coded divine figures, whose roles echo motifs from both mythic archetypes and feminist theologies (

Christ 2003;

Gross 2009). They are not merely symbolic representations, but thresholds through which viewers may encounter a sacredness that is compassionate, relational, and in process.

Rather than asking whether anime “teaches” theology, this article asks how anime activates theological experience and how, in this activation, it reimagines both the world and the God still becoming within it.

2. Methodology

This study proceeds from the idea that theology is not merely the systematization of divine attributes, but the lived process of becoming divine. The concept of theosis, drawn from Eastern Christian traditions (

Stăniloae 2010, p. 516), envisions humanity not as passive before the divine but as invited into active participation with it into a transformative relationship that reshapes both creature and Creator. In the cosmos of anime, however, theosis (

Lossky 2014) is not mediated through institution or creed. It occurs through sacrifice, memory, grief, and care. It manifests in the child who becomes eternity so others may live, or in the wounded rebel who chooses love over vengeance.

In such narratives, the boundary between theology and philosophy begins to blur. Anime does not argue the existence of God in abstract terms, it evokes divinity through absence, rupture, and longing. It stages ontological wounds in worlds where metaphysics is no longer trusted, yet transcendence persists in symbolic form. Questions once posed in scholastic treatises, “What is justice?”, “What is the soul?”, “What survives death?”, resurface in the bodies of magical girls, dying gods, and timelines reconfigured by sacrifice.

While theology has often been understood as the rational articulation of divine truths within specific doctrinal systems, this article adopts a broader, symbolic view. In line with narrative theology and process thought, theology is here conceived as an encounter with the sacred mediated through story, symbol, and transformation. This necessarily opens the term to plural interpretations, Religious, feminist, and post-metaphysical, each offering distinct, yet intersecting, approaches to understanding divinity as becoming.

The methodological framework of this article combines symbolic analysis, narrative theology, and philosophical reflection, drawing particularly on process thought (

Griffin 2017), archetypal psychology (

Jung 2014), and feminist spirituality (

Christ 2003;

Gross 2009). The study focuses on five anime series: Puella Magi Madoka Magica, To Your Eternity, Sunday Without God, Code Geass, and The Promised Neverland, each selected for their engagement with theological themes such as divine absence, co-suffering, memory, care, and spiritual transformation. These works are interpreted not merely as cultural products, but as living texts—aesthetic and affective spaces where viewers are invited into a theological encounter.

Philosopher and theologian Raimon Panikkar offers a framework well suited to this symbolic/theological reading of anime. His concept of the cosmotheandric reality proposes that divinity, humanity, and the cosmos are not separate orders of being, but interwoven dimensions of one unfolding process (

Panikkar 1993). This vision resonates deeply with anime’s metaphysical imagination, where gods are not external rulers but participants in the world’s suffering and renewal. In such narratives, divinity is not encountered from outside, but emerges from within: in grief, in memory, in the act of choosing life for another. Panikkar’s emphasis on relational ontology and the permeability between sacred and profane realms supports the study’s core hypothesis—that theology is not a system to interpret anime, but a horizon activated through it.

From a symbolic/theological perspective, meaning in anime arises through layered, emotionally charged images rather than through systematic doctrines. Paul Ricoeur describes symbol as that which “gives rise to thought” (

Ricoeur 2009)—a double discourse that gestures toward realities otherwise inexpressible. Similarly, Mircea Eliade (

Eliade 2017) interprets myth and symbol as sacred forms that reconfigure ordinary time and space. In this reading, anime offers not theology by proposition, but theology by parable. Characters such as Madoka, Emma, or Mujika serve as symbolic mediators of the sacred, not because they represent doctrinal truths, but because they enact the divine in motion.

This symbolic/theological framework is also grounded in narrative theology. Drawing on Paul Ricoeur, narrative is understood as a mediating form between experience and meaning—a structure that configures time, constructs identity, and enables ethical imagination. Anime, with its ruptured timelines and metaphysical dilemmas, enacts what Ricoeur calls “refiguration”: the reinterpretation of reality through symbolic story. George W. Stroup reinforces this orientation by insisting that theology is not first a system of ideas but rather a confession carried through a story (

Stroup 1984). In anime, theological insight is not explained—it is lived and suffered, evoked through character, memory, and transformation.

To situate this symbolic reading within broader academic discourse, a VOSviewer co-occurrence map was created based on a targeted search in the Scopus database using the terms film and divine (5 July 2025). The top 100 results were analyzed by keyword density, thematic clusters, and chronological distribution. The resulting maps (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) reveal a growing scholarly emphasis on narrative, media theology, divine embodiment, and gendered expressions of the sacred, confirming the interpretive relevance of this study.

The philosophical/theological horizon guiding this work is thus one of emergence, vulnerability, and shared transcendence. Rather than asking whether anime is “theological” or “philosophical,” this study questions whether traditional categories can still hold the mystery that shimmers through these animated worlds and the viewers who meet God there as a calling.

Scholarly interest in the intersection of religion and media has grown significantly in recent decades, with numerous studies investigating how myth, transcendence, and sacred motifs are represented in film, television, digital culture, and even anime (

Buljan and Cusack 2015;

Barkman 2010;

Plumb 2010;

Afanasov 2019;

Tan 2020). Among these, scholars such as Ford contend that media do not merely reflect our existing notions of God, but actively shape and reshape contemporary divine imaginaries, framing God in terms of sound, image, and digital code (

Ford 2015). While prior work has largely focused on religious motifs as representational content, fewer studies explore how specific media forms, particularly anime, enact theology by staging the interplay of sacrifice, memory, longing, and relational transcendence.

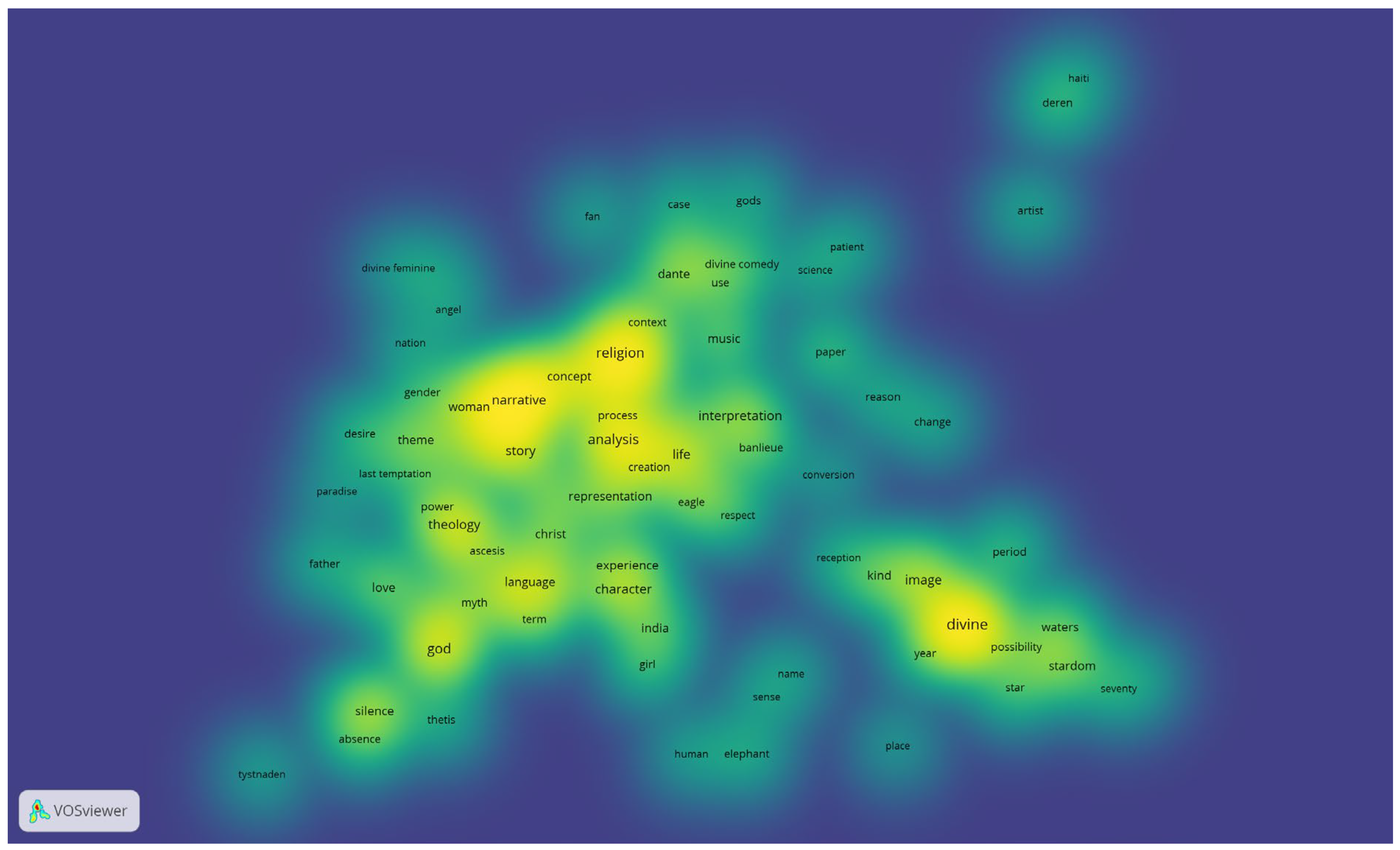

To visualize the current state of research at the intersection of religion, film, and representations of the divine, I conducted a targeted literature exploration using the Scopus database. On the 5 July 2025, I searched for the keywords “film and divine”, which yielded 254 results. I sorted the results by relevance and selected the top 100 documents for analysis. Using VOSviewer, I generated a co-occurrence map based on the text data extracted from these sources. The minimum threshold for keyword co-occurrence was set at five, and the top 100 most frequent terms were included in the visualization. The resulting map (

Figure 1) reveals four major conceptual clusters, highlighting distinct but interconnected domains of scholarly interest. The red cluster focuses on

narrative,

gender,

and theological representation, emphasizing symbolic storytelling, feminist theology, and the use of narrative as a space of religious reflection. The green cluster gathers around

apophatic and mythological theology, with frequent associations with silence, absence, love, and divine mystery—suggesting a turn toward the experiential and ineffable aspects of God. The blue cluster centers on

divine imagery,

media aesthetics,

and reception, foregrounding the role of visual culture and perception in shaping spiritual meaning. Finally, the yellow cluster reflects

marginal artistic and cultural expressions as sources of religious insight. Positioned at the intersection of these clusters, this study contributes a symbolic/theological reading of anime that synthesizes narrative structure, mythic motifs, and theological process. By framing anime as a site of theosis—where divinity is not depicted but

becoming—the article bridges narrative theology and lived reception, expanding the range of media through which contemporary theology can be both practiced and perceived.

A time-overlay visualization of the keyword network (

Figure 2) illustrates how the scholarly conversation around film and the divine has evolved over the last decade. Earlier studies (in blue and green) focused on classical theological and symbolic categories such as

god,

theology, and

representation, while more recent research (in yellow) has shifted toward audience-centered engagement, contextual analysis, and embodied motifs such as the

divine feminine. This article draws upon both layers: it engages with enduring theological questions (e.g., theosis, absence, and myth), while also responding to newer academic trajectories that foreground reception, narrative experience, and contemporary reinterpretations of the sacred. In doing so, the study positions anime not as peripheral entertainment, but as a vital space for exploring the divine becoming through story.

A density visualization of the same co-occurrence network (

Figure 3) highlights the areas of the highest thematic concentration in current scholarly discourse. The most intense zones (in yellow) cluster around

religion,

narrative,

theology,

god, and

divine—revealing a sustained focus on symbolic analysis, classical theological motifs, and religious representation in film. Notably,

story,

myth, and

image also emerge as conceptually rich nodes. This reinforces the centrality of aesthetic and narrative structures in contemporary discussions of the sacred. The present study enters into this dense space while shifting the emphasis toward

theological process,

divine becoming,

gender inclusion, and

viewer participation—themes that appear peripherally yet are crucial to understanding how media and film animate spiritual imagination today.

3. Becoming Divine in Anime Worlds: Case Studies

In this section, we explore how the divine is imagined, embodied, and enacted within selected anime narratives. Each case study, drawn from Puella Magi Madoka Magica, To Your Eternity, The Promised Neverland, Sunday Without God, and Code Geass, presents a distinct pathway to godhood or sacred agency. These are not tales of omnipotence or classical theism, but of transformation, refusal, memory, and ethical authorship. Through their struggles, sacrifices, and symbolic actions, these characters illuminate how divinity is not only transcendent, but also immanent, crafted through love, resistance, and the will to heal what was once broken. This chapter offers philosophical and theological reflections on these “becomings” as modern myths of the sacred.

3.1. Transcendence and Compassion: The Divergent Godhoods of Puella Magi Madoka Magica and to Your Eternity

In Puella Magi Madoka Magica, Madoka Kaname’s transformation into a god-like being unfolds through a final sacrificial wish: she rewrites the metaphysical laws that condemned magical girls to despair. Her ascension is instantaneous and absolute, she becomes the Law of Cycles, a silent, unseen presence who rescues others but ceases to exist within ordinary time. In contrast, To Your Eternity follows Fushi, an immortal being who begins as a featureless orb and learns the world and himself through countless deaths, loves, and memories. His ascent is not a leap but rather a slow walk through the sorrow. He becomes divine not through omnipotence, but through endurance.

These differences are not merely narrative—they reflect divergent theological architectures: divinity as sacrificial transcendence versus divinity as evolving immanence. The comparison reveals not just different models of godhood, but different spiritual grammars. Madoka’s godhood is mythic and apocalyptic; Fushi’s is organic and relational. Their stories embody two theological poles: the apophatic silence of the transcendent and the kenotic compassion of the immanent.

Both characters echo classical divine attributes—omnipotence, omniscience, and impassibility—but do so in narratively transformed ways. Madoka renders omnipotence as redemptive finality; Fushi renders it as the endless capacity to grow, remember, and restore. Their attributes are not static traits but symbolic movements, shaped by sacrifice, care, and memory. The divine, in each case, is not explained but experienced, felt through character, form, and loss.

Their journeys, viewed through the lens of narrative theology, also diverge in structure. Madoka’s path is shaped by the hero’s journey, culminating in cosmic self-erasure: she becomes not a sovereign deity, but a metaphysical law, hope itself. Her divinization occurs through transcendence, through the breaking of causality and temporal finality. Fushi, by contrast, is no redeemer outside time. His divinity grows slowly, through each form he adopts, each death he survives, each connection he cannot let go. His apotheosis is not ascension, but attachment. He becomes divine not by escaping humanity but by going deeper into it.

In Madoka, we meet the God of impossible hope—the one who breaks time for the sake of justice. In Fushi, we meet the God of patience and repair—the one who walks beside us, wounded but still creating. Fans recognize both. Some long for Madoka’s purity; others are comforted by Fushi’s tears. Yet in both, they rediscover an ancient yearning: not for omnipotence but for a God who knows them: one who watches without abandoning (Madoka) or remembers without fleeing (Fushi).

These animated theogonies reveal that anime does not merely depict gods—it enacts divinity in motion. Fushi, in particular, embodies ontological becoming in its purest form. Born without identity or intention, he is becoming through contact, memory, and suffering. His story is not about asserting power or rewriting systems but about growing in depth through every encounter. In Heideggerian terms, Fushi is Dasein unfolding through time—but unlike humans, his telos is not death. It is continuity, the expansion of care, the long memory of love. He is what he has encountered. He does not transcend death like Madoka, nor does he resist it. He outlives it—bearing the scars of others as extensions of himself.

Table 1 crystallizes the fundamental contrast between two modes of divinization: Madoka’s godhood emerges through sudden transcendence, breaking cosmic order in a single act of redemptive erasure, while Fushi’s unfolds through time, shaped by love, memory, and mortality. Whereas Madoka becomes a metaphysical law—an abstract, distant redeemer—Fushi remains relational and embodied, a divine figure who evolves with every life he touches. Their contrasting forms of divinity reflect deeper theological tensions between transcendence and immanence, as well as purity and persistence, and suggest that anime, far from reinforcing a singular image of God, offers a plural and processual vision of the sacred.

Through this juxtaposition, we see how anime constructs plural models of the sacred, staging divine becoming not as a single theological claim, but as a question offered to the viewer. In that open space between transcendence and immanence, silence and touch, and finality and continuity, anime becomes a vessel of holy imagination.

3.2. Refusal and Renewal: Emma and Mujika as Dual Christ Figures in the Promised Neverland

In The Promised Neverland, salvation does not arrive through one messianic figure, but through two: Emma and Mujika, whose actions, human and divine, mirror the ancient Christian vision of Christ as both fully human and fully divine. Their stories unfold not through miracles or ascension, but through ethical resistance, care, and embodied solidarity.

The world of The Promised Neverland is governed by a god-like, primal force that demands children as offerings to maintain balance. This system reflects an ancient sacrificial logic: to survive, someone must be left behind. It is the theology of blood, scapegoats, and justified death. Emma refuses this premise entirely. She insists on saving every child—even the weakest, the slowest, those deemed “acceptable losses.” Her gospel is simple: “No one gets left behind.” She rejects utilitarianism, the politics of fear, and all redemptive violence. She refuses the bargain, refuses the god, and in doing so, becomes a new kind of Christ—not crucified but courageous, not ascended but embedded. Her divinity arises not from nature, but from unshakable commitment: strategic, maternal, uncompromising.

If Emma disrupts the logic of sacrifice, Mujika undoes its very necessity. Called the “Evil-Blooded Girl,” Mujika carries in her body the possibility of peace: her blood allows demons to survive without consuming humans. She is a living alternative to death—not a warrior or prophet, but a quiet, nourishing presence. Mujika does not lead or command; she offers herself as a healing force. Where Emma resists, Mujika redefines. She is salvation not by action, but by being—non-coercive, non-violent, fully available.

Together, Emma and Mujika enact a dual Christology. Emma is the human Christ, walking through suffering to liberate the oppressed. Mujika is the divine Christ, the Logos made flesh not to judge, but to nourish. One leads the exodus; the other heals the wilderness. One challenges the law; the other changes the hunger that sustained it. As we can see in the second table, whereas Madoka Magica offers a transcendent messiah who saves through cosmic erasure, The Promised Neverland roots salvation in the soil of the present. Emma does not ascend. Mujika does not dominate. Both remainwith the broken, the hunted, and the hungry. Their divinity is not manifested through power but through refusal and restoration.

The comparison table (

Table 2) between these three figures clarifies this further:

3.2.1. Starving the Death: The Philosophical and Theological Act of Refusal

Emma and Mujika do not defeat death in the traditional heroic sense. They do not vanquish it, glorify it, or promise to transcend it. Instead, they starve it—slowly, tenderly, and defiantly, by rendering it unnecessary.

In the theological architecture of The Promised Neverland, death is not merely a natural end but a system of exchange, a constructed economy built on the illusion of necessity. Within this structure, hunger is made sacred, sacrifice becomes law, and blood is transformed into currency. Death is sanctified through repetition; its rituals justify suffering, and its logic becomes unquestionable.

Emma and Mujika interrupt this sacrificial economy not by overthrowing it with superior force, but by refusing its terms altogether. Through complementary yet opposite gestures, they disarm the theological and philosophical foundations of death itself.

Mujika’s blood is not a weapon, it is a quiet argument against necessity. When she shares her so-called “miracle blood” with demons, she does not coerce or conquer. She transforms. Her offering is not only a plot point; it marks an ontological rupture: a world where survival no longer depends on consumption, and life no longer necessitates death. In her, the Eucharist is rewritten. No longer a commemoration of sacrificial death, it becomes a celebration of nourishment without violence, a new metaphysics of life given, not taken.

Philosophically, Mujika challenges biological determinism. She suggests that nature, however monstrous, can be rewritten through gifts, not aggression. In this way, she enacts a form of ontological pacifism, a redefinition of being in which to live no longer requires one to consume another. She reprograms the appetite of the world.

Emma, by contrast, offers no miracle. She offers refusal. She starves death not by offering alternatives, but by withdrawing her consent. She refuses to participate in a logic that weighs lives against one another. She dismantles the philosophical traditions that normalize sacrifice: rejecting utilitarianism, which permits the few to die for the many; rejecting contractarianism, which trades security for exclusion; and rejecting political realism, which normalizes violence as necessary. In place of these, Emma practices a messianic ethics of unconditional inclusion. She will not build a better world at the cost of even one child. Her leadership is strategic, determined, and maternal, but never transactional. She does not kill for peace. She fasts from death.

Together, Emma and Mujika enact a theology of immanence—not a flight to another world, but a transformation within this one. They do not eliminate death; they refuse to feed it. Mujika rewrites the biology of consumption. Emma rewrites the ethics of sacrifice. Their combined gesture dissolves the sacred economy of blood and interrupts the metaphysical foundations of a world where killing is sanctified. Their divinity is not earned through power or purity, but through the persistent refusal to make death holy.

3.2.2. Escape as Consequence, Not Reward

At the end of The Promised Neverland, Emma and Mujika do not perish. They do not ascend. They walk together with others into a new world. This is not a reward for obedience. It is not divine compensation for a pious heart. It is the logical conclusion of their refusal to sacrifice. Their salvation is not granted from above but built from below. It is the fruit of an alternative ethics. They escape not because they were willing to die, but because they refused to. The new world they enter is not a paradise bestowed by divine favor, but a world made livable by dismantling the structures of death that defined the old one. Emma undoes the logic of exclusion. Mujika undoes the physiology of violence. Together, they make peace possible.

Theologically, their exit is not a transcendence of the world, but its reformation. Unlike Madoka’s cosmic erasure of pain through metaphysical transformation, Emma and Mujika remain grounded. Their divinity is embodied, shared bread, tired feet, open hands. They do not become gods above, they become architects within. Philosophically, this is a shift from a metaphysics of sacrifice to a praxis of immanence: holiness not as suffering but as solidarity. In this light, their final step is not resurrection, it is rewriting. Not reward, but release. Not miracle, but culmination. They do not become divine by dying well. They become divine by ensuring that no one else has to.

3.2.3. Feminine Divinity and the Theological Imagination

Recent theological discourse has increasingly emphasized feminine representations of the divine, both in historical cosmologies and in contemporary cultural media (

Christ 2003;

Gross 2009). While classical theism often associates God with masculine-coded power—sovereignty, judgment, and transcendence, many symbolic traditions, both Eastern and Western, portray the sacred feminine through compassion, justice, generativity, and relational power.

Within anime, characters such as Madoka, Emma, and Mujika reimagine this sacred femininity not as goddess archetypes in the doctrinal sense, but as theological figures who mediate life, peace, and moral transformation. Each of them refuses domination. Each offers presence, care, and the dismantling of systems built on violence. Their divinity is not based on omnipotence, but on incarnate resistance, maternal strength, and world-renewing love. They invite a re-reading of the divine not as a rule but as a relationship. Not as control, but as care. In this way, anime becomes not only a medium for theological imagination, but a space where the sacred feminine takes form, not as dogma, but as an ethical presence.

3.3. The Silence of God and the Power of Desire: Sunday Without God

While Emma and Mujika embody a divinity forged through refusal, solidarity, and systemic transformation, other narratives approach the sacred from a different angle—one marked not by ethical resistance, but by metaphysical absence. If The Promised Neverland offers a vision of God present in human action and non-sacrificial change, then Sunday Without God confronts us with a world in which God has granted every wish and then abandoned creation. And yet, even in this theological void, something sacred stirs. In the figure of Ai Astin, a young gravekeeper born after the departure of the Creator, we encounter a new kind of divinity, one that does not begin with transcendence or strategic refusal, but with the radical courage to rebuild meaning from the ruins of belief itself.

In Sunday Without God, the creation myth follows the Judeo-Christian pattern, until the seventh day. God creates the world, blesses it, and then, overwhelmed by human desire and the fullness of heaven and hell, repents. On Sunday, He abandons the world. Yet the wishes already made remain. People, fearing death, had once wished not to die. And so, immortality spread across the land: bodies that could not decay, souls that could not rest. Later, humanity longed once more for an end, and from this second wave of collective desire, the Gravekeepers were born: emotionless, pure beings who bury the undead so they may finally find peace.

Thus, desire in this universe is not a moral failing—it is a theological mechanism. The divine responds not through revelation or intervention, but through wish-fulfillment. Reality bends to longing, and longing shapes ontology. Death and life, as well as order and collapse, all follow the arc of desire. The world’s tragedy lies not in God’s wrath, but in His surrender to human want—and in the vacuum that follows. God does not destroy the world. He simply leaves it as it is, corrupted by the wishes He once granted.

Among the Gravekeepers is Ai, a twelve-year-old girl named for love. She is different. Unlike the others, she weeps. She doubts. She chooses. She carries both humanity and mystery. Her journey is not to replace God, but to respond where God has ceased to act. She does not assert divine power, she begins to restore divine presence. She buries the undead, comforts the forgotten, even revives those lost in metaphysical loops. And in each act, she resists the silence left behind. Her father, first known as Hampnie Hambart, then revealed as Kizuna Astin, embodies a distorted image of God: immortal, pained, searching for meaning. He longs not for salvation, but for death. Once he finds his daughter, his only desire is closure. He is crucified, yet briefly resurrected, only to leave behind memory. Ai buries him, not as a worshipper, but as a witness. Not to glorify, but to let him rest. He is a God emptied of hope; she is its renewal.

3.3.1. Desire as Theological Act

In this world without divine law, desire becomes sacred. Not merely in the emotional or erotic sense, but in the ontological sense—desire as that which configures being. The undead remain because they wished not to die. The Gravekeepers exist because people wished to regain the ability to die, so God granted their wish again. The children of Class 3-4 create a time-looped paradise to relive a single joyful summer day. Ai, through her unspoken but active love, breaks the metaphysical logic of this loop, freeing Alice from his scripted death and Dee from her disembodied curse. This is not magic, it is theology. A world shaped by prayer-like longing, where articulation is power.

Ai’s transformation begins when she stops acting out an inherited role (“to bury the dead”) and instead chooses a new purpose: to bring peace to the living, even if it requires breaking the order she was born to uphold. Her shift recalls the Gospel moment when Jesus asks the blind man, “What do you want me to do for you?” (Matthew 20:32), not for information, but to affirm that transformation begins with voiced desire. Likewise, Ai’s desire reopens the closed world. Her actions do not undo God’s abandonment, but they answer it. In a universe bent by wish and weariness, she chooses neither despair nor nostalgia. She chooses care.

3.3.2. A Theology of Repair

If Madoka’s divinity is apocalyptic, erasing and rewriting the cosmic laws of despair, and Fushi’s is evolutionary, growing slowly through memory and sorrow, then Ai’s is something quieter, more grounded: it is restorative. Her divinity does not descend from the heavens or emerge from metaphysical transformation. It takes root in absence, in the silence left when God leaves, and grows through gentle, persistent acts of care.

Ai does not ascend. She does not overcome death through miracle or omnipotence. Instead, she meets death as it lingers, unresolved, and buries it with tenderness. She is not a savior in the messianic sense, nor does she preach a new law. Yet her role is no less theological. She is a midwife of meaning, a quiet architect of the sacred in a world that has forgotten how to name it.

The world of Sunday Without God begins with abandonment. God creates the cosmos, but on the seventh day, overwhelmed by human wishes and the overflowing of heaven and hell, He repents, and departs. But divine absence does not erase desire. The wishes God once granted remain, echoing through reality and reshaping it. People wished not to die, and so they became immortal. Later, they wished for death again, and from this longing emerged the Gravekeepers, emotionless figures who bury the undying. Even God’s departure becomes theological: it is a response to the overwhelming volume and contradiction of human longing. And in this broken aftermath, Ai is born—not as a replacement for God, but as a response to what remains.

She carries no prophecy, only a shovel. And yet she utters the most radical theological sentence in the series: “If God has abandoned the world… then I will make it.” This is not simply a declaration of will, but a fundamental shift in theological posture. In a reality emptied of divine order, Ai does not mourn the silence, she inhabits it. She does not collapse under its weight, she answers it. Her tsukurimasu, her “I will make it,” becomes a sacred verb: an act of creation not from power but from care.

The theology Ai enacts is not one of transcendence or law. It is a theology of hands, of presence, of repair. She does not proclaim belief. She lives it. She tends to what others abandon. She makes sacred space not through a miracle, but through memory. In this, her acts resonate with philosophical echoes: with Sartre’s insistence that meaning must be made, not received; with Nietzsche’s demand to revalue all values in the absence of metaphysical grounding; and with Kant’s call to moral duty even without divine sanction. And yet Ai’s answer surpasses philosophical autonomy. She does not will a new world into being through dominance or solitude. She builds it from the fragments of love.

Her labor recalls tikkun olam, the Jewish call to repair a broken world, but Ai answers this call without commandment. She does not act because she is told to. She acts because something in her refuses to leave the world unmended. Her theology is tactile: the shovel that buries, the smile that comforts, the resolve that refuses to abandon the abandoned.

Where Madoka becomes divine by transcending despair, and Fushi by evolving through remembrance, Ai remains. She stays among the ruins. Her divinity is not metaphysical, not apophatic, not even mystical. It is existential. It is chosen. It is relational. She does not undo death. She honors it. She does not escape the world. She makes it livable. Her theology is not a rupture or a cycle—it is a continuation, a slow refusal to let the sacred decay in silence.

And yet, Ai’s path is not the only possible answer to a world in crisis. Her theology of repair speaks to those who choose to heal. But what of those who, faced with unhealable violence, decide instead to intervene, violently, sacrificially, strategically? What of the ones who choose to become monsters so others might live in peace? Where Ai offers a divinity of persistence, another anime offers a divinity of authorship, a rewriting of history through self-erasure. In Code Geass, we meet Lelouch vi Britannia: not a god of care but a god of consequence. Not the theology of repair, but of radical authorship, by which the divine becomes not what is remembered or tended to but what is willed into being at the cost of one’s own life.

3.4. Lelouch and the Authorship of Fate

If Sunday Without God mourns the absence of divinity and rebuilds the sacred from within the ruins, Code Geass envisions the divine not as lost, but as entangled. In this narrative, divinity is not tender, immanent, or restorative. It is structural: a metaphysical lattice of memory, power, and recursion. Here, God is not a sovereign being, but a total consciousness, the Collective Unconscious, an omnipresent archive of human pain, desire, and history. It is this field that Emperor Charles zi Britannia and Marianne seek to merge with, to suspend the march of time and usher in a world without conflict. This metaphysical union is named Ragnarök.

Yet in one of the most theologically charged moments in anime, Lelouch rejects this vision. In Episode 21 of Code Geass R2, standing before the spiral of ancestral consciousness, he utters a cry that cuts across all cosmic fatalism:

“God—Collective Unconscious—don’t stop the march of time. I want the day of tomorrow.”

This is not a denial of the divine. It is a refusal of a divine role that consecrates paralysis. Lelouch does not destroy God; he interrupts a metaphysical plan that would freeze history into a timeless equilibrium. Ragnarök promises an end to suffering, but only by suspending time, by fusing all minds into one, eliminating both conflict and possibility. This is not peace. It is stasis. It is theological totalitarianism disguised as harmony.

Lelouch’s refusal is philosophical and spiritual. He rejects the myth of bloodless perfection. Instead, he affirms history, messy, painful, and unfinished. His declaration echoes with existential and prophetic force: suffering must not be locked into sacred memory; it must be transfigured through action. If Madoka becomes divine through redemptive sacrifice, Fushi through remembrance, and Ai through gentle repair, Lelouch becomes divine through authorship. His Zero Requiem is not martyrdom. It is an ethical edit—a willing descent into monstrosity so that others may inherit peace. His godhood is not proclaimed. It is misrecognized. He becomes the villain so others may be free.

The Spiral of Memory: Imagining God as Genetic Time

The metaphysical heart of Code Geass is visualized not as a throne or temple, but as a glowing, spiral rope, a double helix of ancestral consciousness stretching toward the sky. In this imagery, the divine is neither external nor transcendent, but deeply encoded—like DNA. The spiral, with its biological and cosmological resonances, becomes a symbol of a God who is not above history, but within it. This God is memory: every soul’s trauma, longing, and vision woven together in eternal recursion.

Here, Code Geass offers a profound symbolic proposal: God is not a creator of history, but the sum of history. The divine is a genetic metaphysics, a spiritual genome co-written by every act of love, hatred, war, and yearning. And because it is constructed, it can be rewritten. This is precisely Lelouch’s task. He does not destroy the divine spiral. He edits it. And in doing so, he asserts a theology of temporal freedom.

Lelouch’s line, “I want the day of tomorrow”, becomes more than narrative defiance. It is theological revolt. He refuses eternity. He insists on becoming. In rejecting Ragnarök, he embraces time as sacred: not a problem to be solved but a space in which healing, growth, and transformation can unfold.

This vision resonates with several intellectual traditions. From a Jungian lens, Lelouch confronts the archetypal depths of the Collective Unconscious, not to be absorbed by them, but to redirect them. In Deleuzian terms, the spiral is not a hierarchy but a rhizome, ever-branching, non-linear, relational. And from Bergson, Lelouch inherits a defense of durée réelle, real time, as the true vessel of creativity. He rejects the static eternal for the generative unfinished.

What Lelouch ultimately offers is not transcendence or refusal, but authorship. He takes on the role of theological editor, reshaping the divine not by invoking purity, but by wielding the impurity of history. His sacrifice is narrative, strategic, performative. He chooses to bear all blame and all hatred so that a new world may be born in his absence. He becomes divine not through adoration, but through anonymity.

In Lelouch, Code Geass imagines a theology of self-erasure through authorship. A God not adored, but necessary. A divine figure who does not save, but scripts the conditions for peace. His death is not for sins—but for structure. He does not atone. He alters. Where others embody hope, compassion, or care, Lelouch embodies the will to revise, an apocalyptic scribe of ethical renewal.

When Lelouch addresses the collective unconscious calling it “God”, he does not simply command; he speaks. His words carry the texture of both a plea and a proclamation: “Don’t stop the march of time. I want the day of tomorrow.” This moment is not a mere assertion of will, it is an invocation. He names the divine field and steps into it not as sovereign, but as a speaker, one who believes that speech, when uttered with intent, reshapes being itself.

Philosophically, this gesture draws on ancient traditions where speech is ontological. To speak is to create. To name is to act. This recalls the Judeo-Christian vision of the Logos: the divine Word that brings order from chaos, that writes reality into motion. In this frame, Jesus is not only the messenger of God, but the Word made flesh—the active speech act through which divinity participates in the world.

Lelouch mirrors this dynamic. He does not destroy the collective unconscious; he joins it. He enters it with the weight of suffering, memory, and moral responsibility. He speaks into the Godfield, not to silence it, but to realign it. His declaration affirms time, insists on futurity, and refuses metaphysical stasis. Like the Logos, his voice is not one of domination but of design, a voice that changes the structure of the world not by force but by narrative.

In Jungian terms, Lelouch descends into the archetypal substratum of human consciousness and returns not with divine command but with transformative presence. In philosophical terms, he enacts authorship: the radical power to rewrite meaning within immanence. And in theological resonance, his final gesture is an echo of divine speech—a human word that carries enough vision to set history in motion again.

Lelouch’s divinity is not in omniscience or metaphysical purity. It is in authorship grounded in suffering. It is in the ethical courage to step into silence and speak, not to dominate, but to participate. To name the world anew, and in that naming, to call tomorrow into being.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This article has traced how anime functions as a contemporary site of divine becoming, where theological imagination and philosophical reflection intersect, collide, and transform one another. Far from reducing theology to metaphor or entertainment, anime reveals how symbolic storytelling can articulate deeply rooted spiritual intuitions: about justice, sacrifice, memory, agency, and transcendence. Characters such as Madoka, Fushi, Emma, Mujika, Ai, and Lelouch do not claim divinity in any classical sense. Rather, they enact pathways of theosis, through sacrifice, through ambition, through love, through memory, through authorship.

The third table (

Table 3) synthesizes the six figures explored in this study, each embodying a distinct divine modality. Their theological gestures do not converge into a single dogma but emerge from tension and paradox: transcendence versus immanence, sacrifice versus refusal, memory versus creative authorship. While some reflect classical attributes of the divine, others disrupt or reconfigure them entirely, offering alternative visions of godhood rooted in relational care, existential ethics, or symbolic transformation.

What emerges here is not a new theology of doctrine, but a theology of participation, where divinity is not a state to be declared, but a vocation to be lived. This vision resonates not with static metaphysics, but with dynamic models such as Raimon Panikkar’s cosmotheandric unity or David Ray Griffin’s process theology, in which the divine is becoming, relational, and responsive. At the same time, it echoes post-metaphysical philosophical traditions—from existential ethics to depth psychology—which privilege narrative, experience, and symbolic integration over abstract absolutes.

Anime, shaped by Japanese religious pluralism and global cultural circulation, does not flatten theology into relativism. It recontextualizes it—transposing the sacred from the fixed sphere of institutional dogma into the open terrain of narrative encounter. In doing so, it does not oppose faith, but reveals how spiritual longing persists beyond doctrine, inviting one to rethink the categories of both theology and philosophy by allowing them to be rewritten through story.

Ultimately, anime stages more than mere representations of God; anime stages experiments in divinity: symbolic acts of theological and philosophical imagination in which meaning is not inherited, but made. In these animated theogonies, the sacred does not descend from above. It rises from within.