Abstract

This article aims to analyze the role of migration in the process of the third demographic transition (TDT) in the context of key mediating determinants, such as migrants’ religiosity and economic conditions in the countries of origin and settlement. TDT refers to population changes resulting from migration as a demographic compensatory mechanism in countries with a low total fertility rate (TFR). The study is based on a network analysis of keywords in the scientific literature using the Scopus database and VOSviewer. The results point to three main research approaches to TDT—investigating quantitative population changes, the sociodemographic consequences of migration, and its effect on urbanization—and to the fact that economic and axionormative determinants are under-researched. This article contributes to TDT theory, pointing to the need for that theory to include cultural, economic, and axiological factors as key determinants influencing the permanence of TDT.

1. Introduction

Demographic changes have been an important element of broader modernization processes for a long time. Demographic transition theories, describing quantitative and qualitative changes in social structure, are set in the context of deep social, economic, and political transformations. Like other processes that accompany modernization, such as technological development, industrialization, or urbanization and the related internal and external migrations leading to changes in social and demographic structure, a demographic transition is one of the key dimensions of social transformations.

This article analyzes the role of migration processes in the mechanism of the third demographic transition. Based on a bibliometric analysis using VOSviewer 1.6.20 for Scopus-indexed articles, it presents the thematic evolution of topics (keywords) addressed in the literature, covering the relations between the processes of social dynamics that accompany international migrations. Involving a change of place of residence, migrations also lead to cultural change, which in turn can influence demographic trends, e.g., personal beliefs and religion can affect individual decisions on childbirth, and thus fertility rates.

The traditional (first) demographic transition (FDT) was defined in the literature as a lasting change in social structure from the “expansive” (prodigal) model, characterized by high total fertility and mortality rates, to a “restrictive” (frugal) model, in which a drop in mortality allowed for the stabilization of population size at lower birth rates (Szukalski 2005; Iglicka 2001). What is also not without significance is the development of science, including medicine and hygiene, which, combined with the improvement of material living conditions, has contributed to an increase in life expectancy (Mathers et al. 2015).

While FDT was shaped by social modernization, leading to a gradual decrease in death and, subsequently, birth rates and to an increase in population size (Caldwell et al. 2007), the second demographic transition (SDT), driven by postmodernization processes such as growing individualism, secularization, and a shift toward self-expression values, was marked by significant changes in family structures, such as parenthood postponement, a decrease in total fertility rate (TFR), and conscious family planning (Lesthaeghe 2014).

However, neither FDT nor SDT take full account of the contemporary demographic trends, particularly in the context of globalization and growing migration flows (Isański et al. 2023b), which led to the development of another theoretical approach—the third demographic transition (TDT). According to this approach, in developed countries it is migration that has been emerging as the main compensatory mechanism for low TFR (Coleman 2006). Migrants’ socially determined reproductive patterns are not homogeneous, however. Research has shown that after settling in the host country, not every group of migrants maintains a TFR as high as in the country of origin—in many cases, migrants adjust their procreation patterns to the host country’s dominant social and economic norms, which may lead to a decrease in this indicator (Gołata 2016). Moreover, according to what is known as the disruption hypothesis, migration can lead to a temporary decrease in TFR due to social disorganization (Thomas and Znaniecki 1920; Mucha 2019) resulting from the process of settlement (Kulu 2005). This decrease may also result from a subjective sense of downward social mobility within a generation, combined with upward social comparison mechanisms. These can be triggered, among other factors, by the financial and emotional costs of adapting to a new country, difficulties in having professional qualifications recognized, or the time required to meet local labor market expectations—such as degree nostrification, learning a technical or sector-specific language (Sorokin 2019), or facing ethnic penalties in recruitment processes (Heath and Cheung 2006).

Despite evidence showing that economic and religious factors are of significant importance for TFR, an analysis of research on TDT shows that these aspects have not been adequately addressed in the literature. This is a significant gap in research into the long-term effects of migration on population structures. Our contribution will therefore be to analyze the TDT and attempt to fill this gap by taking into account the under-researched economic and religious factors in the context of the long-term effects of migration on the demographic structure. TDT postulates that in developed countries characterized by a low TFR, it is migration that has become the main factor in demographic changes, transforming the social structure not only quantitatively, by increasing the size of a given population (Gu et al. 2021), but also qualitatively (Coleman 2006, 2009; Coleman and Scherbov 2005), by changing its racial, ethnic, and age structures. Authors have also observed effects of the demographic transition on social relations (Walaszek and Wilk 2022), economic conditions (Makarski et al. 2025), the increasing cultural diversity and transnationalism (Vertovec 2009), and the integration policies of countries (Deimantas et al. 2024), which makes TDT one of the key demographic issues of the twenty-first century. Nonetheless, these studies have limited capacity in giving a full picture of the changes in the social landscape as a result of TDT, because of the limited attention given to religious and economic factors. We argue that enhancing these studies with rigorous analysis of economic and religious factors would better explain the complexity of TDT processes.

1.1. Religion and Economics Intertwined

The dynamics of TDT not only influence population structure in terms of age and ethnicity but also translate into changes in the religious structure of societies. For example, research by PEW Social Trends (PEW 2017) indicated that differences in TFR and mortality rates influenced the number of people professing each religion in different continents. In sub-Saharan Africa, where Christianity and Islam are dominant, TFR is high for both religions (above 4.0), which contrasts with the low TFR in Europe (1.5 for Christians and 2.1 for Muslims). Moreover, differences in believers’ median age—the lowest being in Africa and the highest being in Europe—reflect the different stages in these regions’ demographic development.

European data concerning the drop in TFR in the years 1960–2022 also indicate a systematic decrease in the value of religion in different countries of Europe and in its mean value for EU27—from a level above 2.00 in Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Hungary, Austria, Finland, and Switzerland and above 3.00 in the Netherlands, Ireland, Poland, Portugal, and Slovakia in 1960 to a mean of 1.46 in 2022 (Eurostat 2023). TFR does not currently reach the replacement level (2.14) in any of the EU countries, except the Faroe Islands (2.71), which, in the long term, will lead to depopulation and the aging of societies (Espinosa 2024). In the face of these processes, migration is becoming the main factor stabilizing population size in Europe, but at the same time transforming its religious and cultural structure. The influx of migrants, especially from high-TFR regions, not only compensates for demographic shortages but also influences procreation patterns in host societies. In the context of TDT, this means that migration (and related mediating determinants) is not merely a compensatory mechanism but a factor shaping both demographic dynamics and structural changes, including those in the domains of religiosity and social integration (e.g., mixed marriages) (Domański et al. 2019).

Research indicates that population flows not only respond to the demographic deficit but also stem from economic disparities, the level of material security, and the policies of countries regarding the labor market and the systems of social benefits (Borjas 2014).

In this context, the effect of migration on TDT is shaped by factors such as the social policy of the destination country, particularly its natalist policy (Fluchtmann et al. 2023). OECD data show that in countries with a stable labor market, wide access to public services, and effective family support policy, migrants can maintain a relatively higher TFR, which contributes to a lasting demographic transformation (OECD 2024; Isański et al. 2021). In countries with limited social support and high costs of living, migrants often adjust their reproductive patterns to local realities, which weakens the potential of migration as a TDT mechanism (Adserà and Ferrer 2016). This was confirmed in the analyses by Okólski (Okólski 2021), which clearly indicated that the migration transition in Poland and other Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries was not only a response to demographic changes but also a result of long-term adaptation strategies associated with economic conditions and with the social policy of the host countries to which CEE economic migrants migrated (such as Germany, France, and the UK).

To fully understand the mechanisms of TDT, it is necessary to take a broader perspective both on the geographical scope of analyses and on the mediating factors that may determine whether migration really leads to lasting changes in the population structure as part of TDT. A particularly important aspect of this process is the role played by the phenomenon of religion, religiosity, and economic factors, such as labor demand, wage gap, remittances, and the system of benefits. They shape the social structure because demographic changes are strictly connected with cultural identity, social norms, and procreation patterns, both among the native population and among migrants, as well as with the economic conditions in the countries of origin and settlement. Considering the above context, the article aims to present a bibliometric analysis of the role of migration in the process of TDT, with special focus on mediating variables. It recommends broadening the theoretical perspective on TDT by including religious and economic determinants as factors shaping both demographic dynamics and integration processes in host societies.

1.2. Research Questions

In view of the above, we argue that it is therefore legitimate to pose the following research questions:

- How have the definitions and operationalizations of TDT evolved in research to date?

- What are the trends in the thematic areas of TDT that can be observed over time?

- Are there any other mediating determinants that influence the effectiveness of migration as a TDT mechanism which have not been given sufficient attention?

- What is the main geographical focus of current TDT research, and which areas require more research?

1.3. Fundamental Theoretical Framework

This article is based on the theoretical foundations of the TDT theory, according to which contemporary demographic changes are no longer determined exclusively by birth and death rates and changing marital patterns, but are increasingly shaped by migration flows, including international migration (Coleman 2006, 2009). It seems insufficient, however, to assume that migration automatically compensates for a low rate of natural increase in population. The mere presence of migrants in the host society does not necessarily mean permanent demographic change because the characteristics of migration and its effect on population structures can differ depending on the social, economic, and cultural contexts (Gołata 2016; Kulu 2005; Sorokin 2019). To better understand the mechanisms of TDT, it is necessary to consider the mediating determinants that influence the effectiveness of migration as a demographic factor. Two areas seem crucial: economic and cultural factors (above all, religious ones) that influence migrants’ reproductive patterns and their adaptation to host societies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Direct and indirect determinants of TDT.

The present article also draws on several supplementary theoretical frameworks that make it possible to explain why migration alone is not a factor sufficient to cause permanent demographic changes:

Economic theories of fertility (Becker 1981; Caldwell 1982; Caldwell et al. 2007)—stating that reproductive decisions are strictly linked to economic conditions, child-raising costs, and employment stability.

The NELM theory (Stark and Bloom 1985)—stressing that migration is not only an individual decision made in response to wage differences but a strategy of households, enabling economic and demographic risk management. In the context of TDT, this means that the impact of migration on demographic processes depends on economic conditions in the host country and on migrant families’ adaptation strategies.

The post-materialism theory (Inglehart 2020)—emphasizing that in developed countries, changes in social values (self-fulfillment, autonomy) may reduce willingness to have children.

The theory of religion as a vehicle of pro-family attitudes (McQuillan 2004)—asserting that religion influences procreation decisions not only through faith itself but also through the social norms it shapes. In religious communities, the normative value of family and strong gender roles may promote higher TFRs, which is particularly visible among migrants from certain religious backgrounds.

Post-secularism and the assimilation of religious migrants (Berger et al. 1999; Berger 2014)—although migrants from religious communities initially have higher TFRs, with time their reproductive patterns gradually adjust to the host country’s norms. However, religiosity can slow down the pace of this adjustment, with the result that in some Western societies migrants’ TFR in the first and second generations remains higher than the mean for the native population (e.g., Muslim communities in France, Orthodox Jews in Europe) (Potančoková et al. 2018). Synthesizing the economic, cultural, and religious perspectives outlined above enables a more nuanced conceptualization of TDT—one that views migration not as a simple compensatory mechanism for low fertility, but as part of a complex interplay between demographic behavior, institutional context, and value systems.

2. Methodology

The study involved a bibliometric analysis aimed at determining dominant trends and identifying gaps in TDT research. This method was considered the most appropriate as it enables a systematic and quantitative identification of dominant themes and research gaps within the dispersed, interdisciplinary literature on TDT. It also offers the advantage of visualizing conceptual relationships, supporting a deeper interpretation of field-specific developments (Kirby 2023; van Eck and Waltman 2017). Scopus-indexed research publications served as an empirical basis for the analysis. The database was chosen due to its broad thematic scope, the high quality of bibliometric data included, and its reputable standing in academia, particularly in the field of social sciences.

The publication search process was iterative and involved between ten and twenty verification trials testing different search strategies. Initially, we applied broad general queries about TDT; then, we narrowed them down to terms strictly related to migration, TFR, and structural changes in the population. We used combinations of various expressions linked with TDT, including “fertility transition”, “demographic shifts”, “population replacement through migration”, and “long-term fertility patterns”. The database search was conducted between 3 and 28 February 2025. Ultimately, it yielded a set of 326 research articles, which was deemed a sufficient sample for an in-depth bibliometric analysis. This number ensured thematic saturation of the field and allowed for stable clustering results in VOSviewer, as bibliometric research typically recommends a minimum of 200–300 sources to generate meaningful keyword and citation networks (Kirby 2023; van Eck and Waltman 2017). The sample includes publications from a wide temporal range, encompassing both foundational and contemporary works on the subject of TDT.

VOSviewer

The analysis of the collected bibliometric data was performed using VOSviewer software. We applied the default normalization settings of this tool (association strength). This normalization method is widely used in bibliometric research, as it adjusts for the varying frequency of keyword occurrences and highlights the relative strength of conceptual links. It was selected to ensure the comparability of term co-occurrence and to enhance the interpretability of cluster structures (Kirby 2023).

The search was based on logical operators (Boolean search) (Sutton et al. 2023), which made it possible to eliminate the articles that were only tangentially related to the concept of TDT. The search did not cover the full text of articles but only their key elements, which ensured greater precision and narrowed the results down to relevant publications.

In this way, we identified author and index keywords. The minimum number of occurrences for a keyword to be included in the analysis was set at five. The analysis used different methods available in VOSviewer, including co-occurrence analysis, co-citation analysis, bibliographic coupling, and co-authorship analysis. Eventually, to perform thematic clustering, we applied the Louvain modularity algorithm, which enabled the most accurate reproduction of the structure of relations between the concepts investigated (van Eck and Waltman 2017). This made it possible to create a network map that showed the dominant thematic clusters as well as key terms and their interrelations.

A potential limitation of the present study lies in the exclusive reliance on publications indexed in the Scopus database, which may have affected the overall comprehensiveness of the literature analyzed. To address this concern, an additional verification was conducted using the Web of Science (WOS) database. The comparison confirmed that, while WOS contains important demographic works, the vast majority of them are also indexed in Scopus. Consequently, Scopus was deemed the most suitable source for this bibliometric analysis due to its broader thematic coverage and a higher number of directly relevant publications on TDT, migration, and fertility-related topics.

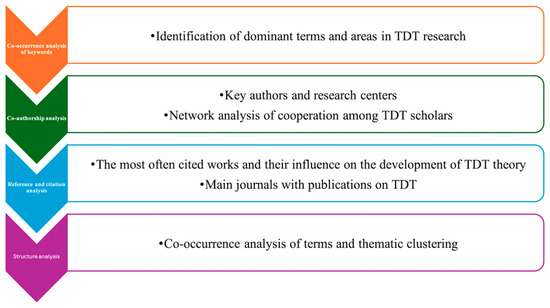

The structure of the bibliometric analysis of studies on TDT is presented in Figure 2, which illustrates the key stages of the study, including the analyses of keywords, co-authorship, and citations.

Figure 2.

Structure of the bibliometric analysis of studies on TDT.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Thematic Links in the Scopus Database (n = 326)

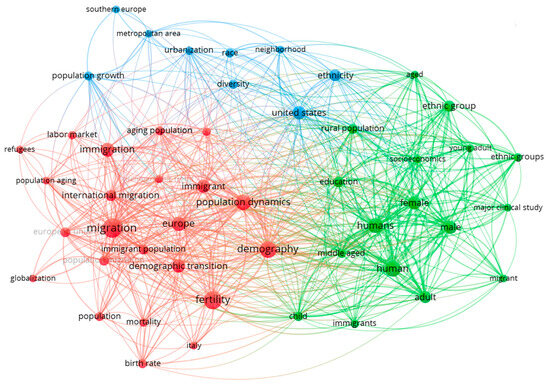

What emerged from the results are three thematic clusters—Migration (red), Human (green), and Urbanization (blue)—covering the key aspects of TDT (Figure 3). These clusters were named after the terms with the highest values of total link strength (TLS), namely those that most often co-occurred with other terms across the analyzed literature. As opposed to “Links”, indicating the number of unique connections with other terms, TLS measures the total strength of these connections.

Figure 3.

Analysis of thematic links in research on TDT.

3.1.1. RED: Migration

The red cluster (Migration1) includes key terms such as “migration” (30 occurrences, 93 TLS), “fertility” (26 and 79, respectively), “demography” (22 and 124), “population dynamics” (19 and 128), and “Europe” (16 and 85). The network of links indicates that the main aspects of TDT concern population changes resulting from international migration, TFR, and demographic structure. It should also be noted that areas strictly associated with TDT are very clearly visible in this cluster.

The Most Frequent Terms

The strong (numerous) links between migration, population dynamics, and demography indicate a broad context of the structural changes resulting in population from migration processes. The co-occurrence of these terms suggests that what is particularly important in research on TDT is the analysis of migration flows and their effect on the demographic composition of societies.

The next important term in this cluster is fertility, which shows the significance of studies concerning the effect of migration on TFR. The relationship between migration and TFR may reflect the differences in birth rate between migrant groups and those of the host countries and the differences in age structure between these populations.

The presence of the term “Europe” indicates that a considerable proportion of analyses concern migrations in the European continent, which supports earlier observations concerning the regional orientation of research on TDT. The high strength of the links shows that Europe is an important research area, where changes in the level of migration, TFR, and demographic structure are particularly visible.

Cluster-Unique Term

The analyzed cluster includes the term “refugees”, which is absent from other clusters. The presence of this term indicates researchers’ interest in forced migration and its consequences for demographic and social structures. In particular, studies address differences in the dynamics of settlement between refugees and other migrant groups and their effects on demographic indicators, including TFR and age structure.

Cross-Cluster Links

The links between clusters indicate that migration is strongly correlated with the second cluster we analyzed—labelled “Human” and marked by the color green (see Figure 3). Our bibliometric analyses show that the links between clusters indicate that migration is strongly correlated with the second cluster we analyzed—labelled “Human” and marked by the color green (Human). Particularly significant links are between the terms “humans”, “ethnic group”, “socioeconomics”, and “education”, which suggests that migration has an impact not only on changes in the population’s size but also on its ethnic diversity, education level, and social structure. Strong links with the terms “male” and “female” point to studies on issues that include gender differences in migration processes and on their consequences for the labor market and demography.

As far as links within the blue cluster (Urbanization) are concerned, migration is strongly linked with the concepts of “urbanization”, “metropolitan area”, and “population growth”, which attests to the fact that migration is seen as one of the key factors influencing the development of cities and their demographic structure. The term “United States” indicates frequent analyses of migration in the American context, while “Southern Europe” suggests that this region has been particularly intensely explored in research on the consequences of European migration processes.

3.1.2. GREEN: Human

The green cluster (Human) covers the aspects of ethnic diversity, age structure, gender, and socioeconomic status. The most frequent terms include “human” (21 occurrences, 176 TLS), “humans” (18 and 167, respectively), “female” (14 and 138), “male” (13 and 134), “ethnic group” (10 and 69), and “child” (7 and 68). The network of links indicates that what has received special attention in the context of TDT is gender, ethnic, and generational differences and their effects on social structures.

The Most Frequent Terms

The central term, “human”, refers to general studies on the characteristics of the population as a whole, whereas the term “humans” indicates analyses concerning specific individuals or human groups. Strong links between these terms suggest that studies cover both explorations of broad demographic processes and more detailed analyses of social differences between individuals.

Another important issue is gender differences, demonstrated by the high strength of the links between the terms “female” and “male”. Strong links between these and other terms from the same cluster indicate that studies analyze the influence of gender structure on access to education, the situation in the labor market, and the use of social services.

Another significant research area is ethnic structure, as evidenced by the presence of the term “ethnic group” and its numerous links. This attests to scholars’ interest in ethnic diversity issues in the context of migration and demographic changes. Additionally, the term “child” points to age structure analysis, including studies on TFR, family structure, and generational processes.

The Unique Aspect of the Cluster

The distinctive element of this cluster is the strong connection with social categories including gender, age, and ethnic differences, which are not as strongly present in other clusters. While in the red cluster (Migration) the dominant terms are ones associated with population movements and the classic determinants of TDT (e.g., “migration”, “fertility”, “mortality”), and in the blue cluster (Urbanization) the main emphasis is placed on the spatial distribution of the population, the green cluster (Human) is mostly focused on identifying the sociodemographic characteristics that define populations in the context of global changes.

Cross-Cluster Links

Links between clusters indicate that the Human cluster is strongly correlated with terms from the Migration (red) cluster. The links with “demography”, “population dynamics”, and “fertility” are particularly significant, which suggests that studies on social structure are strictly associated with analyses concerning qualitative changes in the population2.

In relation to the Urbanization (blue) cluster, the Human cluster is linked through the terms “urbanization” and “ethnicity”, showing that many studies analyze the spatial distribution of the population in the context of ethnic diversity and social divisions. The strong link with the term “United States” indicates that a large proportion of studies concern the social and demographic dynamics in the USA, especially in the context of migration and urbanization.

3.1.3. BLUE: Urbanization

The most frequent terms in the blue cluster (Urbanization) include “urbanization” (12 occurrences, 94 TLS), “population growth” (10 and 78, respectively), “ethnicity” (9 and 72), “United States” (15 and 84), “neighborhood” (7 and 65), and “diversity” (6 and 60). The network of links shows that the key aspects of TDT in this cluster are urbanization processes, population distribution, and ethnic structures in the regional context. The most frequent term is strongly linked with “population growth” and “neighborhood”, which suggests that studies in this area are focused on the spatial distribution of the population and demographic growth rates in the context of cities.

The second important issue in this cluster is ethnicity, which points to the analysis of ethnic diversity in cities and regions. Links with the terms “diversity” and “United States” suggest that some studies concern the ethnic characteristics of the population in the USA, where urbanization and migration strongly influence social structures.

Also strongly represented are concepts associated with the urban space and its social effects, as evidenced by the usage of the terms “neighborhood” and “metropolitan area”. The strong link with spatial analysis suggests that what plays an important role in urbanization research is spatial analysis methods which make it possible to study population distribution patterns and city structures.

The Unique Aspect of the Cluster

The element distinguishing this cluster is the presence of the term “neighborhood”. This suggests that what is particularly significant within this cluster is analyses concerning local social structures and the effect of migration and urbanization on their formation, especially in the context of specific urban and regional spaces.

Cross-Cluster Links

Urbanization shows numerous and strong links with terms from the red (Migration) cluster, particularly “migration”, “international migration”, and “population dynamics”. This points to the analysis of the impact of migration on urbanization processes and on the development of the demographic structure of cities. The strong link with “aging population” suggests that studies also include the issues of population aging in the context of urbanization.

The Urbanization cluster links with the green (Human) cluster through the terms “ethnicity”, “rural population”, and “United States”, which suggests that studies analyze both internal migrations and ethnic differences in urban structures in the region of North America. The presence of strong links with “rural population” may point to the analysis of contrast between urban and rural areas in the context of demographic changes.

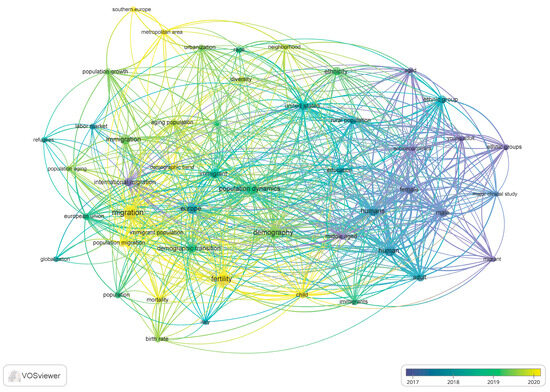

3.2. Analysis of Temporal Links in the Scopus Database (n = 326)

The analysis of temporal links in the network suggests an evolution of TDT-related research interests. The colors indicate the time range in which a given term occurs in the literature, with dark blue nodes representing older/earlier publications and yellow and green nodes more recent publications (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Temporal analysis of thematic links in research on TDT.

3.2.1. Early-Stage Research Themes (Up to 2017)

The earliest publications on TDT (up to 2017) concentrate on themes such as “human”, “ethnic group”, “socioeconomics”, “female”, “male”, and “education”, which indicates an early interest in social and demographic structure in the context of TDT. These concepts are particularly present in the Human cluster, which suggests that studies on gender, ethnic, and socioeconomic differences constituted one of the first currents of analysis in this area.

3.2.2. The Breakthrough Period (2018/2019)

The strong links between the terms “population growth”, “Europe”, and “demographic transition” suggest that between 2018 and 2019 scholarly publications increasingly addressed demographic change in Europe in connection with long-term migration effects. This concentration of co-occurring terms suggests that, during this period, literature on the TDT began to focus more prominently on migration as a central factor shaping population structures and social dynamics—a perspective that had not been strongly emphasized in the earlier literature.

3.2.3. The Latest Trends (After 2019)

Recent studies (since 2019) combine terms that were only peripherally explored before, thus indicating a change in the direction of analyses. The topics associated with the Human cluster disappear, which suggests that issues concerning sociodemographic characteristics cease to function as a separate line of research and get absorbed by other areas of analysis.

Their disappearance is accompanied by an increase in the significance of terms such as “metropolitan area” and “diversity”, which used to have a marginal role in research on TDT. This attests to the growing interest in the effect of demographic processes on the structure of cities and in changes regarding the social diversity of populations.

4. Discussion

Existing studies on TDT have defined this process in different ways, depending on the research approach, which is reflected in the structure of thematic clusters. Each of the clusters presents TDT through a different lens, highlighting different mechanisms and consequences of this phenomenon.

4.1. How Have the Definitions and Operationalizations of TDT Evolved in Research to Date?

The Migration cluster paints a picture of TDT as a process of quantitative demographic changes in which migration plays a compensatory role for low TFR and rapidly aging population. In this approach, the key factor in TDT is international migration as a mechanism stabilizing population dynamics, particularly in developed countries, with what has been termed a demographic deficit. The operationalization of TDT in this approach was based on the analysis of indicators such as TFR, mortality rate, population dynamics, and migration flows. Studies focused on the effect of migration on maintaining a stable population size and age structure, especially in aging societies. This stems from the fact that population aging and the long-term decline in fertility rates generate increasing burdens on social welfare and health care systems, and migration is perceived as an important factor making it possible to temporarily relieve those burdens and ensure the demographic stability of the host country (Lamnisos et al. 2021).

The Human cluster frames TDT as a qualitative population transformation process, encompassing changes in its sociodemographic structure such as shifts in age distribution, gender balance, and ethnic composition. From this perspective, migration not only changes the population’s size but also influences its internal heterogeneity and social structure. Operationalization in this cluster was based on indicators concerning the division of the population according to age (“young adult”, “child”, “middle age”), gender differences (“male”, “female”), ethnic structure (“ethnic groups”), and access to education (“education”). Studies focused mainly on the effect of migration on the population’s sociocultural diversity and integration processes in host societies, one of the reasons being that the growing social diversity generates both development opportunities but also new integration challenges that have a significant impact on the sociopolitical stability of host countries (Abu Nawas et al. 2022). The complexity of the relationships between social groups, stemming from their forced coexistence, often leads to challenges regarding social cohesion and cultural integration, requiring a deeper understanding of adaptation, education, and diversity management processes (Bhattarai and Yousef 2025).

The Urbanization cluster frames TDT as a spatial relocation process in which migration shapes urbanization dynamics and settlement structure. From this perspective, TDT is not limited to change in population size but also includes changes in the spatial distribution of the population and the influence of this distribution on the development of cities and regions. In this approach, operationalization included indicators associated with urbanization (“urbanization”), population distribution in metropolitan areas (“metropolitan area”), and the structure of neighborhoods (“neighborhood”). Studies focused on the analysis of how migration influenced the development of cities, spatial segregation, and the transformation of metropolitan areas (Buonomo et al. 2024; Randolph 2024).

To sum up, studies to date have approached TDT from three perspectives: as a process of quantitative changes in the population compensated for by migration (Migration), as a qualitative sociodemographic transformation influencing age structure, gender structure, and ethnicity (Human), and as a spatial relocation and urbanization process (Urbanization). The operationalization of these approaches used different indicators, which shows that TDT is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, analyzed in various demographic, social, and spatial contexts.

The explanation of this state of affairs may lie in the evolution of factors shaping the demographic processes and the changing role of migration in the global population ecosystem. For a long time, research on TDT focused mainly on analyzing demographic processes within countries, but the events of recent decades, especially the migration crisis in Europe and North America, have significantly changed the directions of analysis.

However, the causes of migration should be sought also in the structural factors that shaped human mobility even before the escalation of conflicts and political crises. The economic crisis of 2008 (the Great Recession) caused an increase in unemployment and deepened economic disparities, which particularly influenced migration dynamics in Europe. Its outcomes varied—while in Greece and Spain unemployment rates rapidly increased, the German labor market improved, which translated into the directions of internal migration. In the USA, recession led both to an increase in migration between states and to an influx of new migrants from Latin America (Jauer et al. 2019).

Additionally, migration in Europe was shaped by the expansion of the European Union in 2004 and 2007, which opened Western European markets for workers from Central and Eastern Europe. After the crisis of 2008, this phenomenon intensified when countries such as Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria experienced economic difficulties, which induced many citizens to migrate in search of more stable employment conditions (Fel et al. 2023).

Apart from internal migration in the EU, in 2015 Europe faced another challenge—the mass influx of refugees from outside the Union. Germany, Austria, and Greece received hundreds of thousands of applications for asylum, mainly from refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, and North Africa, which strengthened the perception of migration as not only an economic phenomenon but also a humanitarian and political issue (Bermudez and Roca 2024).

Another significant factor behind increased migration was the policy of free movement of people in the EU, which enabled the fast movement of people between regions affected by the crisis and countries with more stable economies. In consequence, migration from the south of Europe (Spain, Greece, Italy) to northern EU countries (Germany, formerly the UK, and Scandinavian countries) became one of the main demographic trends after 2010. Similar processes were taking place in the USA, where the influx of migrants from Latin America intensified as a result of violence perpetrated by gangs as well as economic and political crises, especially in Mexico, Venezuela, and the countries of Central America. This phenomenon was particularly visible after 2014, when the USA began to record a growing number of juvenile migrants crossing the border, and 2018 saw the beginning of mass migrant groups travelling on foot through Mexico towards the USA (Gómez Johnson and Gil 2022).

As a result, the role of migration in TDT (González and González-González 2018) models was broadened—from the treatment of migration exclusively as a population-stabilizing factor to analyses of its long-term consequences for labor markets, integration policy, and the spatial reorganization of cities. Themes in the Human cluster, shown in Figure 3, became particularly important, since the migration crisis revealed that demographic processes could not be analyzed in isolation from their social consequences. The influx of people with different cultural and educational characteristics influenced age, gender, and ethnic structures of the population in host countries, giving rise to new challenges associated with integration, social identity, and disparities. Moreover, the increased heterogeneity of societies forced a revision of educational policies, the labor market, and health care systems, which was reflected in research on TDT. This process also revealed the significance of adaptation mechanisms in multicultural societies, including the changing patterns of social relations and sense of belonging.

At the same time, notions represented within the Urbanization cluster became more prominent, because mass migration not only changes population structure but also shapes spatial dynamics. The influx of people into urban areas contributed to the intensification of urbanization processes, the deepening of spatial segregation, and increased pressure on the infrastructure of cities, where migrants settled more often than in non-urbanized areas.

4.2. What Trends in the Thematic Areas of TDT Can Be Observed over Time?

The analysis of temporal links showed how research trends associated with TDT evolved over just a few years. In early studies, researchers focused, above all, on sociodemographic characteristics, analyzing social structure through the lens of gender, ethnicity, and education levels (Coleman 2006). The transitional period brought an increased interest in migrations, their demographic consequences, and transformations in the structure of the European population, which were also reflected in the existing literature (Iontsev and Subbotin 2018; Lichter et al. 2007). Latest research reveals the emergence of new directions of analysis, including special interest in urban areas and problems stemming from the growing diversity of urban populations. Researchers began to notice cities as areas particularly sensitive to migration processes and their social consequences, such as increasing ethnic and cultural diversity (Ananta et al. 2016; Bao and Chen 2019).

This evolution of interests suggests a shift of the center of gravity in research from general demographic and ethnic analyses towards issues associated with the social consequences of migrations, social integration, and urbanization. The increase in significance of urban issues and social diversity indicates scholars’ growing awareness of the complexities of contemporary societies and the need to integrate different research perspectives (White 2024). Changes of this kind are a response to real problems faced by today’s societies: aging population, fast urbanization, and increasing cultural and ethnic diversity (Han and Hermansen 2024; Tarvainen 2018).

In view of the above, it is reasonable to ask if there are other, underemphasized mediating determinants so far, that influence the effectiveness of migration as a TDT mechanism?

Economics

As noted earlier, existing studies on TDT treated migration as a mechanism compensating for low TFR in developed countries, but they rarely included economic factors influencing the effectiveness of this process. The bibliometric analysis revealed that aspects such as the economic security of individuals, elaborate social welfare systems, and employment stability are not sufficiently considered in studies as mediating determinants of TDT. What seems important is the reference to the NELM theory, which emphasizes that migration decisions are made at the household level rather than individually. In the context of TDT, this means that migration is not only a mechanism compensating for a low rate of natural increase in population but also a strategic tool that allows households to adjust to changing socioeconomic conditions. While models proposed by Becker (Becker 1981) and Easterlin (Easterlin 1975) focus on individual determinants of fertility, Becker’s approach in particular emphasizes the role of opportunity costs in shaping reproductive decisions. These costs refer to the potential benefits individuals forgo when choosing childbearing over alternative uses of their time and resources, depending on the economic and social context of different generations. In contrast, the NELM theory emphasizes that migration can serve as a mechanism influencing these processes by improving household economic conditions and financial stability.

The above-mentioned theories complement the understanding of TDT, stressing that the effectiveness of migration as a demographic transformation mechanism depends not only on migration policy and the situation in the labor market but also on the adaptation strategies of households, which may react to the changing economic and social conditions in different ways (Isański et al. 2023a). Countries with a stable labor market, a well-developed family policy, and wide access to social services can contribute to a higher TFR among migrants, which means that migration not only compensates for the low rate of natural increase in population but also creates conditions for permanent demographic transformation. A contemporary analysis of migrations to Poland revealed that, in Poland, migrants initially maintained a higher TFR than the local population, but in the long term their reproductive patterns became similar to the host country’s norms, which suggests that the effectiveness of migration as a TDT mechanism depends also on integration and adaptation processes (Isański et al. 2021, pp. 385–87). In countries with uncertain economic conditions, high costs of living, and limited social benefits, migrants may avoid permanent settlement or adjust their reproductive patterns to the local realities, which weakens the potential of migration as a TDT mechanism (Isański et al. 2023a, pp. 6–7).

At the same time, as shown by the experience of developed countries, family-friendly policies, such as parental leave, nurseries, and tax exemptions, may prove to be insufficient in the long-term formation of procreation decisions because they do not solve young adults’ key problems, such as the economic instability present in specific countries as well as globally, the lack of stable employment, and difficulties in finding the right partner. As a result, although support systems can partly alleviate the economic barriers to having children, in countries with high economic uncertainty and with changing social norms they are not a sufficient incentive to increase fertility rates, which means their effect on TDT processes remains limited (Lesthaeghe and Zeman 2024).

Moreover, the postmaterialism theory (Inglehart 2020) states that changes in societal values within developed countries may negatively influence people’s willingness to have children, which means that even in a stable economic environment migrants may adopt the demographic patterns of the local population. This effect can be linked with broader cultural and social processes that translate into a decrease in TFR. Lesthaeghe and Surkyn (Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 1988, p. 3) stress that cultural and ideational values are not merely a passive reflection of economic conditions but themselves shape life and demographic decisions.

One of the key mechanisms behind the decline in TFR is the shift of individuals’ priorities from material needs to “higher order” needs, such as self-fulfillment or individualism (Inglehart 2020), which Lesthaeghe and Meekers refer to as the process of departure from “familism” and traditional family norms (Lesthaeghe and Meekers 1987, p. 226). The research conducted by Frejka and Westoff showed that in Western Europe the decrease in TFR was strongly linked with a growing secularism and a declining influence of religion on everyday life (Frejka and Westoff 2008, p. 6).

In the context of migration, this means that migrants settling in countries with high levels of secularization and individualism gradually adopt the values of the local population, which leads to a convergence of fertility patterns. Schnabel notes that in countries with a high level of secularization, both religious and non-religious people are characterized by lower values of TFR, which suggests that the social context of the place of settlement has an effect on procreation strategies regardless of individual beliefs. A similar phenomenon is observed in the USA, where progressing social changes lead to a gradual decrease in TFR in successive generations of migrants despite a higher level of religiosity compared to Europe (Schnabel 2016, p. 2).

The convergence of fertility patterns clearly suggests that migrants’ TFR is a result of adaptation processes in a new environment rather than an independent determinant of TDT. Migrants’ TFR is not a static factor but a part of the dynamic process of interaction with the cultural and social context of the country of settlement. If migrants in the first wave of migration have a higher TFR, their presence does temporarily support a higher TFR in the place of settlement, even if in the long term a convergence with the local population occurs. An analysis of migrations to CEE indicated the migrants initially had higher TFRs than the local population, but with time their reproductive patterns adjusted to the norms of the host country (Schnabel 2016, p. 10). It should be noted, however, that migration does not always lead to the full convergence of fertility patterns. In some cases, it can even reinforce traditional family values, which means that the effect of migration on migrants’ TFR is not homogeneous and depends on the sociocultural context (Isański et al. 2023a).

Mateusz Łakomy (Łakomy 2024) warned against the oversimplified treatment of migration as a “substitute” for natives’ TFR. Postponing real actions aimed at increasing the TFR in anticipation of migration-related solutions may aggravate the problem of low TFR, resulting in demographic challenges intensifying rather than subsiding with time. These findings are consistent with the earlier assumptions that a simplified approach to migration in TDT, without reference to mediating factors, leads to excessive theoretical reductionism. This means, among other things, that the role of migrants’ TFR in TDT should be considered in a long-term perspective, including both the initial effect of maintaining the TFR and the subsequent adaptation processes, shaped by the sociocultural and economic contexts of both the country of origin and the country of settlement.

4.3. Are There Any Other Mediating Determinants That Influence the Effectiveness of Migration as a TDT Mechanism Which Have Not Been Given Sufficient Attention?

Values and Religion

The analysis of keywords revealed no terms associated with religion, value systems, or cultural norms, although the literature on migration repeatedly indicates their significant role in shaping migrants’ reproductive patterns (McQuillan 2004). Studies show that migrants from religiously conservative societies, where family values are strong, often have a higher TFR than the local population (Liu and Kulu 2025). The lack of references to this aspect in the analyzed studies suggests that the cultural and religious determinants of TDT remain under-researched, which is an important gap in the existing literature.

The long-term effectiveness of migration as a TDT mechanism may depend on whether migrants maintain their religious and cultural norms in the host country or adjust to the local demographic patterns (Young et al. 2025). In developed countries, where the dominant system of values is the postmaterialistic one (e.g., focus on personal autonomy, limitation of the number of children for the sake of career development), immigrants may gradually adopt these patterns, which weakens the long-term effect of migration on population growth (van der Kop et al. 2025).

From the theoretical perspective, the lack of references to these aspects in the network of TDT links points to the insufficient use of theories connected with the role of religion and social values in migration processes. In particular, the theory of religion as a vehicle of pro-family attitudes (Heaton 2011, p. 452) suggests that social norms shaped by religions may favor a higher TFR among migrants, which is particularly visible in the case of religious communities.

The effect of religion on fertility is complex and varies depending on religion and denomination. In traditional Catholic communities, pro-family norms are often deeply rooted, which leads to higher TFRs, while in Protestant contexts fertility rates can be more varied and dependent on the level of religious practice (van der Kop et al. 2025, p. 407). In research on developing countries it was found that Muslims more often had larger families than Christians, though these differences might disappear with the increase in the level of socioeconomic development (Heaton 2011, p. 452). In developed countries, such as Finland, the effect of religion on fertility turned out to be less clear, and differences between religious groups were relatively small (Kolk and Saarela 2024, p. 2).

Religion shapes procreation patterns both through social norms and through institutional control. Its impact is the strongest in a situation in which religious norms are clearly specified, consistently enforced, and combined with religious institutional support (Bhattarai and Yousef 2025). Where religious institutions have the strongest impact on everyday life, it is possible to observe phenomena such as a more restrictive approach to contraception and greater emphasis on a large family model. The study by Fehoko and Shaw (Fehoko and Shaw 2023) concerning Pacific Christian migrants in New Zealand found that they perceived offspring as a “gift from God” and that social and religious pressure to have children was considerably strong. In such societies, religion and religiosity not only shape fertility patterns but also influence procreation patterns.

Kolk and Saarela (Kolk and Saarela 2024) also observed that TFR was higher among individuals who married within their religious group, which suggests that religion worked not only at the individual level but also through social norms held within diasporas. In multireligious societies, an additional mechanism is observed—in conditions of religious competition, groups may strive for a higher TFR as a strategy for increasing the number of believers (Lutz et al. 2019). This is not a universal phenomenon, however. In Scandinavian countries, such as Finland, secularization processes contribute to the general decrease in TFR, and differences between religious groups become less clear (McQuillan 2004).

Religious conversions are another significant factor shaping the relationship between religion and fertility. Finnish research showed that individuals who had changed their religion had a TFR similar to that of the group they joined, which suggests that religion works as an adaptive mechanism (Kolk and Saarela 2024). In the French context, it was found that a significant factor was not self-reported religious affiliation but the level of religious practice—those who regularly attended religious services had a higher TFR than nominal Catholics. This means that religion and religiosity determine TFR not only through self-reported religious beliefs but also through engagement in religious practices and through the internalization of related norms (Baudin 2015).

To sum up, the effect of religion on procreation patterns is not homogeneous and depends on a number of factors, including the degree of institutionalization of religious norms, the scale of secularization in a given society, and the dynamics of religious competition (Stonawski et al. 2016). In societies with strong religious control, pro-family norms favor a higher TFR, but in countries with weaker influence of religious institutions, such as Finland or France, individual religiosity increasingly becomes a more significant predictor of TFR than religious affiliation itself (Bagavos 2019).

This process is dynamic—the theory of postsecularism and the religious assimilation of migrants (Baudin 2015) suggests that, with time, migrants’ reproductive patterns may gradually conform to the norms of the host country (Gołata 2016). However, the pace of this process depends the religiosity level of a given migrant—in strongly organized religious communities, such as Muslim or Orthodox Jewish communities in Europe, TFR in the first and second migrant generations remains higher than the mean for the native population (Potančoková et al. 2018). This means that even though the secularization of the host society favors a gradual convergence of procreation patterns, in some religious groups TFR may continue to be high for a long time, which results from the strength of community norms and institutional religious support. From the perspective of TDT analysis, this means that religiosity is a significant factor moderating the effect of migration on long-term changes in population structure in developed countries, influencing both the pace and the direction of changes.

4.4. What Is the Main Geographical Focus of Current TDT Research and Which Areas Require More Research?

The existing studies on TDT have focused mainly on developed countries, in which the processes of population aging and increased migration were most visible. Western and Northern Europe, especially the UK and Germany, were analyzed for ethnic changes and growing population diversity (Berger et al. 1999; Berger 2014). Nordic countries, such as Sweden or Norway, attracted researchers’ attention due to the increasing role of migration in compensating for workforce deficits and their effect on social mobility (Tarvainen 2018). The USA, as a country with a long history of immigration, was analyzed in the context of social disparities stemming from the expanding presence of ethnic minority populations (Lichter et al. 2007) and changes in family structures (Bao and Chen 2019). In Central and Eastern Europe, studies have focused on the problem of depopulation and the strategies of population policy in doubly aging societies (Iontsev and Subbotin 2018) (McQuillan 2004). Studies concerning South-East Asia have been devoted to the changing ethnic pattern and the impact of migrations on social structures, as in the case of Indonesia (Ananta et al. 2016). Finally, studies on secularization and religious changes in the context of TDT have focused mostly on Northern Europe (Kaufmann et al. 2012).

The network analysis of links shows a lack of clear representation of certain regions of the world, including CEE. This is despite countries such as Poland, the Czech Republic, or Hungary—after many years of negative migration balance—increasingly becoming migration destinations (Isański et al. 2023a). As observed by Okólski (Okólski 2021), this region is currently experiencing a migration transition that differs considerably from the patterns previously observed in Western Europe. It involves not only incoming labor migrants, but also the return of former emigrants and increased circular and temporary mobility. This complexity may partially explain the region’s under-representation in existing cross-national analyses.

5. Conclusions

Our analysis indicates that, to date, studies on TDT have focused mainly on quantitative changes in social structure in specific countries resulting from migration as a compensatory mechanism for low TFR, ignoring significant long-term factors involved in this process. At the same time, analysis of bibliometric data revealed an observable failure of investigators to sufficiently include measurable mediating variables, such as economic variables (e.g., labor market structure, employment indicators, migrants’ income level) and cultural or religious ones (e.g., religiosity indicators, religious practice level, the secularization level of societies), which might be correlated with changes in demographic indicators reflecting the structure of specific populations.

Our contribution to the TDT theory consists in indicating that the effectiveness of migration as a driving force of TDT should not be analyzed in isolation from those measurable economic determinants and from the broadly defined world of values, religion, and religiosity. This is because ignoring these mediating variables leads to a simplified perception of TDT as a universal and unidirectional process, while its dynamics are strongly varied depending on spatial, social, and institutional contexts.

In the context of future research on TDT, it therefore seems important to expand the theoretical and empirical framework of analysis to include these economic, cultural, and religious mediating variables. Operationalizing these factors in the form of specific measurable indicators—such as migrants’ TFR, the level of maintaining fertility norms from the country of origin, indicators of change in religiosity levels in successive generations (e.g., frequency of religious practice, self-reported religious identity), economic indicators determining the settlement of migrants (e.g., employment stability, migrants’ median income compared to the native population, real estate ownership indices), and social integration indicators (e.g., mixed marriage rate, command of the language of the host country, participation in local social organizations)—will make it possible to more precisely define the limits and conditions of the effectiveness of migration as a mechanism shaping twenty-first-century demography, thereby allowing for a better understanding of the interactions between migration and long-term demographic changes in host countries.

The new scale of migration after 2004, particularly from CEE countries, offers a renewed perspective on the relationships between migration, religiosity, and fertility in Europe. Migrants from this region, often characterized by higher levels of religiosity and fertility, have made a significant contribution to demographic replenishment in Western European societies. In this context, both religiosity and migration emerge not merely as accompanying phenomena but as essential, though previously underrepresented, components that complement and enhance the theoretical framework of the TDT.

6. Limitations

While this article provides a synthetic overview of the evolution of TDT research based on a bibliometric analysis, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this method. By relying solely on keywords from publications indexed in a single database (Scopus), the study may not fully capture the empirical and theoretical depth of the broader scholarly landscape. Therefore, future research should complement bibliometric approaches with quantitative studies (e.g., based on survey or administrative data) and qualitative investigations (e.g., in-depth interviews with migrants or discourse analysis). Such methodological triangulation would allow for a deeper understanding of how migration influences demographic structures, religiosity, and fertility-related decisions. Moreover, it would support a more culturally grounded and context-sensitive development of TDT theory.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., J.I., M.O., B.D. and A.d.M.; methodology, B.D., J.K. and J.I.; software, B.D., J.K. and J.I.; validation, B.D., J.K. and J.I.; formal analysis, M.O.; investigation, A.d.M.; resources, J.I.; data curation, B.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K., J.I., B.D., M.O. and A.d.M.; writing—review and editing, M.O. and A.d.M.; visualization, J.K., B.D. and J.I.; supervision, J.I.; project administration, J.I.; funding acquisition, J.I. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article. Database based on Scopus search.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | A distinction should be noted: the capitalized terms Migration, Human, Urbanization refer to entire clusters, whereas the non-capitalized terms placed in quotation marks—“migration”, “human”, and “urbanization”—should be treated as keywords. |

| 2 | The use of qualitative in this context refers to non-quantitative features of demographic change (such as shifts in composition or structure), and not to the character of the research methodology. |

References

- Abu Nawas, Kamaluddin, Abdul Rasyid Masri, and Alim Syariati. 2022. Indonesian Islamic Students’ Fear of Demographic Changes: The Nexus of Arabic Education, Religiosity, and Political Preferences. Religions 13: 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adserà, Alícia, and Ana Ferrer. 2016. The Fertility of Married Immigrant Women to Canada. International Migration Review 50: 475–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananta, Aris, Dwi Retno Wilujeng Wahyu Utami, and Ari Purbowati. 2016. Declining Dominance of an Ethnic Group in a Large Multi-Ethnic Developing Country: The Case of the Javanese in Indonesia. Population Review 55: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagavos, Christos. 2019. On the Multifaceted Impact of Migration on the Fertility of Receiving Countries. Methodlogical Insights and Contemporary Evidence for Europe, the United States, and Australia. Demographic Research 41: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Luoman, and Feinian Chen. 2019. From the Classic to the Third Demographic Transition: Grandparenthood across Three Cohorts in the United States. In Grandparenting: Influences on the Dynamics of Family Relationships. New York: Springer Publishing Company, pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudin, Thomas. 2015. Religion and Fertility. The French Connection. Demographic Research 32: 397–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Gary Stanley. 1981. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter. L. 2014. The Many Altars of Modernity: Toward a Paradigm for Religion in a Pluralist Age. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH and Co KG. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L., Jonathan Sacks, David Martin, Abdullahi A. An-Na’im, Tu Weiming, George Weigel, and Grace Davie. 1999. The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez, Anastasia, and Beltrán Roca. 2024. The Impact of Intersecting Crises on Recent Intra-Eu Mobilities: The Case of Spaniards in the UK and Germany. International Migration 62: 145–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, Keshav, and Mahmoud Yousef. 2025. Demography, Language, Ethnicity, Religion, and Refugee Crises. In The Middle East: Past, Present, and Future. Edited by Keshav Bhattarai and Mahmoud Yousef. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 45–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjas, George J. 2014. Immigration Economics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buonomo, Alessio, Federico Benassi, Gerardo Gallo, Luca Salvati, and Salvatore Strozza. 2024. In-between Centers and Suburbs? Increasing Differentials in Recent Demographic Dynamics of Italian Metropolitan Cities. Genus 80: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, John C. 1982. Theory of Fertility Decline. Cambridge: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, John C., Bruce K. Caldwell, Pat Caldwell, Peter F. McDonald, and Thomas Schindlmayr. 2007. Demographic Transition Theory. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, David. 2006. Immigration and Ethnic Change in Low-Fertility Countries: A Third Demographic Transition. Population and Development Review 32: 401–46. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, David. 2009. Divergent Patterns in the Ethnic Transformation of Societies. Population and Development Review 35: 449–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, David, and Sergei Scherbov. 2005. Immigration and Ethnic Change in Low-Fertility Countries–Towards a New Demographic Transition. Paper presented at Population Association of America Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, PA, USA, March 31–April 2. [Google Scholar]

- Deimantas, Vytenis Juozas, Şanlıtürk, A. Ebru, Leo Azzollini, and Selin Köksal. 2024. Population Dynamics and Policies in Europe: Analysis of Population Resilience at the Subnational and National Levels. Population Research and Policy Review 43: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domański, Henryk, Bogdan Mach, and Dariusz Przybysz. 2019. Otwartość Polskiej Struktury Społecznej: 1982–2016 [Openness of Polish Social Structure: 1982–2016]. Studia Socjologiczne, 25–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, Richard A. 1975. An Economic Framework for Fertility Analysis. Studies in Family Planning 6: 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, Catalina. 2024. Total Fertility Rate in Europe in 2023, by Country. Hamburg: Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/612074/fertility-rates-in-european-countries/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Eurostat. 2023. Population Structure and Ageing. Luxembourg City: Eurostat—European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=365039andtitle=Population_structure_and_ageing%2Fpl (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Fehoko, Edmond S., and Rhonda M. Shaw. 2023. From Burdens to Blessings: A Pacific Perspective on Infertility and Assisted Reproductive Technologies in Aotearoa|New Zealand. In Sex and Gender in the Pacific. Edited by Angela Kelly-Hanku, Peter Aggleton and Anne Malcolm. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fel, Stanisław, Jarosław Kozak, Marek Wodawski, and Jakub Isański. 2023. Dilemmas Faced by Polish Migrants in the Uk Concerning Brexit and Return Migration. Christianity-World-Politics 27: 201–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluchtmann, Jonas, Violetta van Veen, and Willem Adema. 2023. Fertility, Employment and Family Policy: A Cross-Country Panel Analysis. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frejka, Tomas, and Charles F. Westoff. 2008. Religion, Religiousness and Fertility in the US and in Europe. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie 24: 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołata, Elżbieta. 2016. Estimation of Fertility in Poland and of Polish Born Women in the United Kingdom. Studia Demograficzne 169: 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- González, Alejandro López, and María Jesús González-González. 2018. Third demographic transition and demographic dividend: An application based on panel data analysis. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series 42: 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Johnson, Cristina, and Adriana González Gil. 2022. Violent Contexts and “Crisis” in Mexico-Central America and Colombia-Venezuela Cross-Border Dynamics, 2010–2020. In Crises and Migration: Critical Perspectives from Latin America. Edited by Enrique Coraza de los Santos and Luis Alfredo Arriola Vega. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Danan, Kirill Andreev, and Matthew E. Dupre. 2021. Major Trends in Population Growth around the World. China Centers for Disease Control CDC and Prevention Weekly 3: 604–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, JooHee, and Are Skeie Hermansen. 2024. Wage Disparities across Immigrant Generations: Education, Segregation, or Unequal Pay? ILR Review 77: 598–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Anthony, and Sin Yi Cheung. 2006. Ethnic Penalties in the Labour Market: Employers and Discrimination. Oxford: Oxford Brookes University. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, Tim B. 2011. Does Religion Influence Fertility in Developing Countries. Population Research and Policy Review 30: 449–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglicka, Krystyna. 2001. Migration Movements from and into Poland in the Light of East-West European Migration. International Migration 39: 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglehart, Ronald F. 2020. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iontsev, Vladimir A., and Alexander A. Subbotin. 2018. Current Scenarios for the Demographic Future of the World: The Cases of Russia and Germany. Baltic Region 10: 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isański, Jakub, Jaroslav Dvorak, Siim Espenberg, Michał A. Michalski, Viktoriya Sereda, Hanna Vakhitova, and Julija Melnikova. 2023a. From the Source to Destination Countries: Central and Eastern Europe on the Move (as Usual). In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Problems. Edited by Rajendra Baikady, S. M. Sajid, Jaroslaw Przeperski, Varoshini Nadesan, M. Rezaul Islam and Jianguo Gao. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isański, Jakub, Marek Nowak, Jarosław Kozak, and John Eade. 2023b. The New Parochialism? Polish Migrant Catholic Parishes on the Path of Change. Review of Religious Research 1: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isański, Jakub, Michał A. Michalski, Krzysztof Szwarc, and Renata Seredyńska. 2021. Fertility Potential and Child Benefits Questioned: Polish Migration in the UK and Changes of Family Policies in Poland. Migration Letters 18: 381–99. Available online: https://migrationletters.com/index.php/ml/article/view/1165 (accessed on 1 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Jauer, Julia, Thomas Liebig, John P. Martin, and Patrick A. Puhani. 2019. Migration as an Adjustment Mechanism in the Crisis? A Comparison of Europe and the United States 2006–2016. Journal of Population Economics 32: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Eric, Anne Goujon, and Vegard Skirbekk. 2012. The End of Secularization in Europe?: A Socio-Demographic Perspective. Sociology of Religion: A Quarterly Review 73: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, Andrew. 2023. Exploratory Bibliometrics: Using Vosviewer as a Preliminary Research Tool. Publications 11: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kolk, Martin, and Jan Saarela. 2024. Religion and Fertility: A Longitudinal Register Study Examining Differences by Sex, Parity, Partner’s Religion, and Religious Conversion in Finland. European Journal of Population 40: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulu, Hill. 2005. Migration and Fertility: Competing Hypotheses Re-Examined. European Journal of Population/Revue Européenne de Démographie 21: 51–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamnisos, Demetris, Konstantinos Giannakou, and Mihajlo Jakovljevic. 2021. Demographic Forecasting of Population Aging in Greece and Cyprus: One Big Challenge for the Mediterranean Health and Social System Long-Term Sustainability. Health Research Policy and Systems 19: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesthaeghe, Ron, and Dominique Meekers. 1987. Value Changes and the Dimensions of Familism in the European Community. European Journal of Population/Revue Européenne de Démographie 2: 225–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesthaeghe, Ron, and Johan Surkyn. 1988. Cultural Dynamics and Economic Theories of Fertility Change. Population and Development Review 14: 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesthaeghe, Ron, and Krystof Zeman. 2024. The New Fertility Postponement in Europe and North America and the East-West Contrast, 2010–19. Genus, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesthaeghe, Ron J. 2014. Second Demographic Transition: A Concise Overview of Its Development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA—PNAS 111: 18112–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichter, Daniel, J. Brian Brown, Zhenchao Qian, and Julie Carmalt. 2007. Marital Assimilation among Hispanics: Evidence of Declining Cultural and Economic Incorporation? Social Science Quarterly 88: 745–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Chia, and Hill Kulu. 2025. Competing Family Pathways for Immigrants and Their Descendants in Germany. International Migration Review 59: 411–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, Wolfgang, Gemma Amran, Alain Bélanger, Alessandra Conte, Nicholas Gailey, Daniela Ghio, Erofili Grapsa, Katherine Jensen, Elke Loichinger, and Guillaume Marois. 2019. Demographic Scenarios for the Eu: Migration, Population and Education. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Łakomy, Mateusz. 2024. Demografia Jest Przyszłością. Czy Polska Ma Szansę Odwrócić Negatywne Trendy? [Demography Is the Future: Can Poland Reverse the Negative Trends]. Warszawa: Prześwity. [Google Scholar]

- Makarski, Krzysztof, Joanna Tyrowicz, and Piotr Żoch. 2025. Demographic Transition and the Rise of Wealth Inequality. Warsaw: Foundation of Admirers and Mavens of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers, Colin D., Gretchen A. Stevens, Ties Boerma, Richard A. White, and Martin I. Tobias. 2015. Causes of International Increases in Older Age Life Expectancy. The Lancet 385: 540–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuillan, Kevin. 2004. When Does Religion Influence Fertility? Population and Development Review 30: 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, Janusz. 2019. The Polish Peasant in Europe and America and the Missing Ethnic Leaders. Przegląd Socjologiczny 68: 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2024. Society at a Glance 2024: Oecd Social Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okólski, Marek. 2021. The Migration Transition in Poland. Central and Eastern European Migration Review 10: 151–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEW. 2017. The Changing Global Religious Landscape. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/04/05/the-changing-global-religious-landscape/ (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Potančoková, Michaela, Sandra Jurasszovich, and Anne Goujon. 2018. Consequences of International Migration on the Size and Composition of Religious Groups in Austria. Journal of International Migration and Integration 19: 905–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, Gregory F. 2024. Does Urbanization Depend on in-Migration? Demography, Mobility, and India’s Urban Transition. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 56: 117–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, Landon. 2016. Non-Religion and Fertility Worldwide: Considering Contextual Effects. Paper presented at 2016 Annual Meeting Population Association of America, Washington, DC, USA, March 31–April 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin, Pitirim A. 2019. Social and Cultural Mobility. In Social Stratification, Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective, 2nd ed. Edited by D. Grusky. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 303–8. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Oded, and David E. Bloom. 1985. The New Economics of Labor Migration. The American Economic Review 75: 173–78. [Google Scholar]

- Stonawski, Marcin, Michaela Potančoková, and Vegard Skirbekk. 2016. Fertility Patterns of Native and Migrant Muslims in Europe. Population, Space and Place 22: 552–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, Anthea, Hannah O’Keefe, Eugenie Evelynne Johnson, and Christopher Marshall. 2023. A Mapping Exercise Using Automated Techniques to Develop a Search Strategy to Identify Systematic Review Tools. Research Synthesis Methods 14: 874–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]