Alevis and Alawites: A Comparative Study of History, Theology, and Politics

Abstract

Islamists, both Muslim and Western, have had a way of absorbing the point of view of orthodox Islam; this has gone so far that Christian Islamists have looked with horror on Muslim heretics for teaching doctrines which are taken for granted coming from St. John or St. Paul.---M.G.S. Hodgson1

1. Introduction

2. Intra-Muslim Diversity and Those Beyond the Pale: Alevis and Alawites in Islamic Context

3. Distinctive Features of Alevi and Alawite Traditions14

Historical Origins and Sociocultural Characteristics

4. Theology and Metaphysics: Gnostic Dualism Versus Mystical Monism

4.1. Comparative Eschatologies

4.2. Figures of Veneration

4.3. Communal Structures and Religious Leadership

4.4. Ritual Practices and Gender Inclusivity

4.5. Religious Holidays and Commemorations

5. Parallel Histories of Persecution and Marginalization

5.1. The Mamluk and Ottoman Periods

5.2. The Modern Era: A Time of Paradox

6. The Alevi–Alawite Political Rapprochement in the Wake of the Syrian Civil War and After

7. Conclusions and Epilogue

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | For the Alevis’ unequivocal rejection of a Shiʿi identity, see (Shankland 2012, pp. 210–28). By contrast, while some Alawites—particularly among the religious elite—emphasize affinities with Shiʿism, whether due to political considerations or personal conviction, lay Alawites frequently distinguish themselves from mainstream Imami Shiʿis. Indeed, medieval Alawite texts often refer to Imami Shiʿis as ẓāhiriyyat al-shīʿa (“the external Shiʿis”) or muqaṣṣira (“the deficient ones”), underscoring a significant doctrinal distance. See (Friedman 2010, p. 200; Bar-Asher and Kofsky 2002, p. 112). Formally as well, neither group has historically maintained institutional ties or mutual recognition with Imami Shiʿism in matters of religious authority or legal tradition. |

| 3 | While “Alevi” and “Alawite” became the commonly used names by outsiders in the 19th and early 20th centuries, respectively, there is evidence suggesting that both terms were used as emic self-appellations by group members for centuries. For early uses of the term “Alevi”, see (Karakaya-Stump 2019, p. 34, n. 18; Gülten 2016, pp. 27–43; Akın 2023, pp. 18–50). For early uses of the term “Alawite”, see (Alkan 2012, pp. 23–50). |

| 4 | The metaphorical and nonconformist approach to religious formalities found among Alevis, and among the kindred Bektashi Sufi order, is most poignantly illustrated in their poetry and in Bektashi jokes. The following excerpt from a poem by the Bektashi poet Rıza Tevfik, frequently performed by Alevi musicians, is a good example:

For Bektashi jokes, see (Svendsen 2012). For a rare attempt to justify Alevis’ allegorical interpretation of sharia on the basis of relevant Qurʾanic verses, see (Öztoprak 1990, esp. 1–38, 66, 102–30). For the allegorical interpretation of sharia in the Alawite tradition, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 130–43; Bar-Asher and Kofsky 2002, pp. 66–67, 82–83, 114–7). |

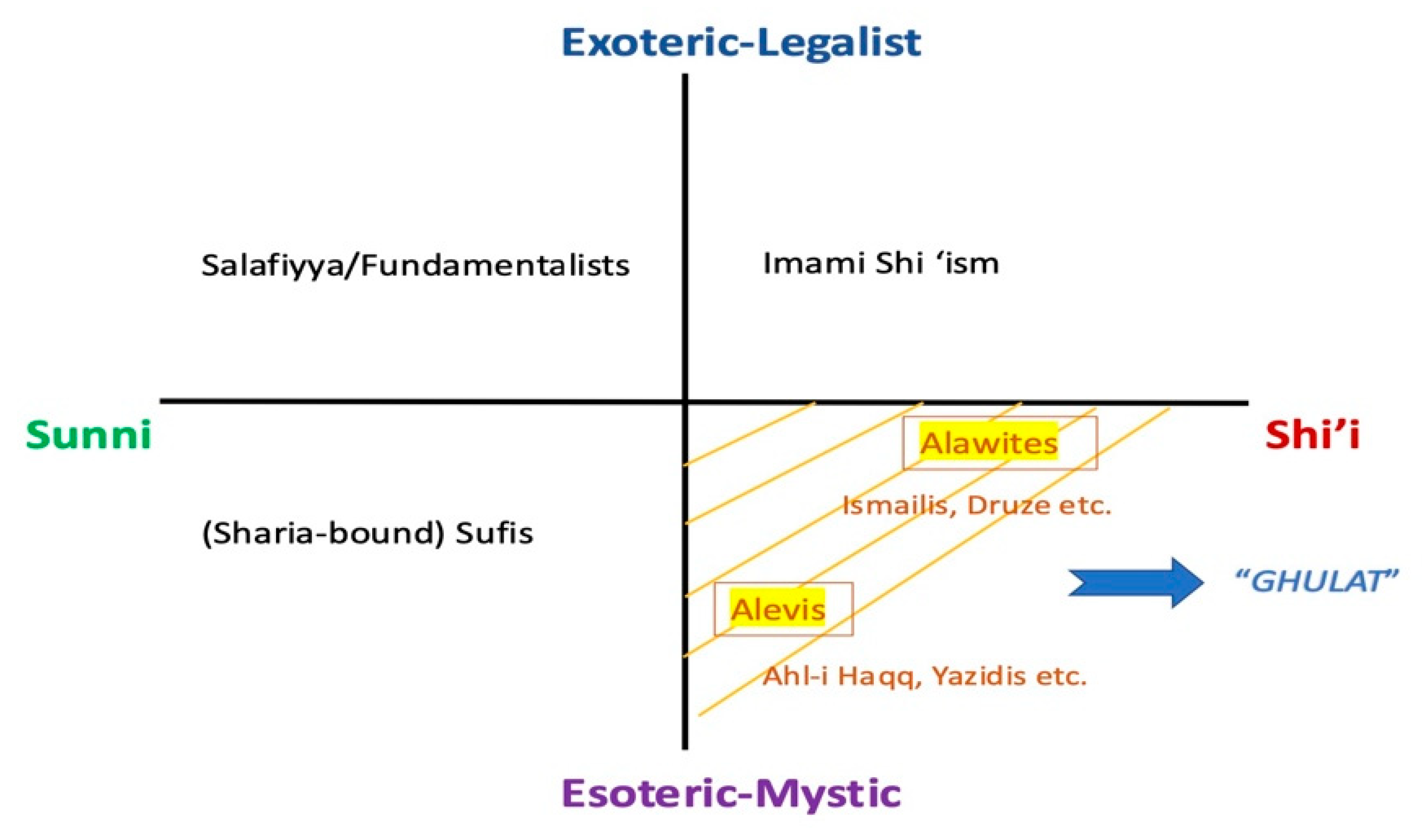

| 5 | For discussions of the term ghulāt and its semantic and historical development, see (al-Qadi 1976, pp. 295–319; Hodgson 1955, p. 8; Asatryan 2017). Since medieval times, some Muslim heresiographers have conveniently attributed the origins of the ghulāt to a subversive plot allegedly orchestrated by an insincere Jewish convert, aiming to undermine Islam from within by introducing corrupt innovations (bidʿa). On this narrative, see (Barzegar 2011, pp. 207–31). |

| 6 | See, for example, (Moosa 1988), in which a number of distinct groups are subsumed under the category of “Extremist Shiites”, reflecting a reductive interpretation of their theological conceptions of divinity. By contrast, some contemporary scholars have sought to reclaim and deploy the term ghulāt in a more analytically self-aware and neutral manner. See, for instance, (Friedman 2010, p. 3). |

| 7 | A notable example of the ahistorical use of syncretism as a taxonomic tool in relation to the groups in question is (Kehl-Bodrogi et al. 1997). |

| 8 | For a discussion of the pitfalls associated with uncritical and ahistorical uses of the concept of syncretism in Alevi-Bektashi studies, see (Karakaya-Stump 2019, pp. 13–14; Stoyanov 2010, pp. 261–72). For a broader critical examination of the concept of “syncretism”, including its intellectual genealogy, analytical limitations, and potential utility, see the selection of articles in (Leopold and Jensen 2004), as well as the introduction to (Shaw and Stewart 1994). See also (Maroney 2006), which offers insightful case studies demonstrating a more historically grounded application of the term in specific contexts. |

| 9 | Among the Alevis—and, to a much lesser extent, the Alawites—their relationship to Islam, or the perceived lack thereof, remains a subject of ongoing debate. In the case of the Alawites, this debate tends to be confined largely to online platforms and social media, whereas among the Alevis, it has also taken the form of polemical exchanges in published books and articles. For example, see (Bulut 1997), which advocates for a conception of Alevism entirely divorced from Islam, and the polemical response in (Aktaş et al. 1998), where a group of Alevi authors reject the idea of an Alevism severed from Islam or its Islamic elements. |

| 10 | For the idea of divine manifestation in Alawite and Alevi traditions, see (Olsson 1996, pp. 167–83, esp. 178–79; Eyüboğlu 1990, pp. 237–38, 245–46). |

| 11 | For a comprehensive exploration of the historical Sufi origins of Alevism, see (Karakaya-Stump 2019). |

| 12 | For a comprehensive and synthesized account of Alawite history and doctrine, see (Friedman 2010). |

| 13 | For the development of sharia-centered Imami Shi‘ism, see (Hodgson 1955; Stewart 1998). |

| 14 | The following discussion of Alevi and Alawite religious beliefs and rituals draws not only on the existing secondary literature, but also on my own fieldwork and conversations with community members—spanning over three decades in the case of Alevi–Bektashi communities, and several years with Alawite communities. Citations, however, are confined to published sources. This is partly due to the impracticality of naming the many individuals I have engaged with over the years, and partly—especially in the case of the Alawites—out of respect for the community’s general preference for anonymity. |

| 15 | While the Kizilbash/Alevis and Bektashis are nearly identical in their beliefs and rituals, they historically diverged in terms of organizational structure and political orientation. Since the abolition of the Bektashi order in 1826, however, the two groups have largely converged in these areas as well, particularly within Turkey. It is also worth noting that earlier generations of scholars often referred to the Kizilbash/Alevis reductively as “village Bektashis”. For an overview of the complex historical relations between the Kizilbash/Alevis and the Bektashis, and their more recent convergence, see (Karakaya-Stump 2019, Chapter 3). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | Karakaya-Stump (2019) The Kizilbash-Alevis in Ottoman Anatolia, especially Chapters 1, 2, and the Conclusion. Specifically on the radical dervish groups that formed the historical backbone of the Kizilbash/Alevi communities—most notably the Abdals of Rum—who were integral to the late medieval renunciatory currents within the broader Sufi framework, see (Karamustafa 1994, especially Chapter 6). Also see (Eyüboğlu 1990, pp. 213–300; Dönmez 2004, pp. 53–67). |

| 18 | For the conceptualization of Kizilbashism as a latter-day ghulāt movement, see, for instance, (Tucker 2014, pp. 191–92). |

| 19 | For a basic list of venerated figures in the Alevi–Bektashi tradition, see (Saltık 2004). |

| 20 | On the formation of the Kizilbash movement and the resilience of the Alevi communities in Anatolia, see (Karakaya-Stump 2019, especially, esp. Chapters 4 and 5). |

| 21 | On Muhammad ibn Nusayr and the naming of the original community, see (Friedman 2010, p. 11). |

| 22 | On medieval Alawite theologians succeeding Muhammad ibn Nusayr, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 13, 39, 47–48, 71). |

| 23 | On Khasibi, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 17–30). |

| 24 | For the public statement regarding the desecration of Khasibi’s tomb by the Federation of Alawites in Europe, see (Federation of Alawites in Europe 2024). According to Nibras Kazimi, an Iraqi writer who conducted fieldwork in Syria and visited Khasibi’s shrine in the summer of 2006, the shrine is attributed by the local Sunnis to Sheikh Yabruq, a Rifa‘i sheikh. According to Kazimi, the Alawites themselves accept this identification in order to conceal the true identity of the person entombed at the site out of fear of Sunni retaliation. See (Kazimi 2010, p. 60, n. 74). |

| 25 | On the Alawites’ settlement in the coastal regions of the Levant, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 41–42, 47–48). |

| 26 | For the early history of the Alawites, see (Massignon 1913–1936; Halm 1960; Friedman 2010, Chapter 1). |

| 27 | This is, of course, not to suggest that Alidism or Shiʿism and Sufism were insular movements. On the contrary—despite ultimately evolving along distinct socio-historical trajectories—both traditions share religious ideas rooted in the complex and intertwined histories of early Sufi and Alid movements, with ongoing contextual intersections continuing to shape their development over time. Marshall Hodgson, in this regard, aptly observed that the Sufis were the “evident successors” to the Ghulāt in regard to broad questions such as “the spirituality of the soul and the possibility of its communion with God”, despite the absence of any “immediate connection” between the two (Hodgson 1955, p. 8). For the broader issue of the multifaceted relationship and mutual influences between Shiʿism and Sufism, see (Hodgson 1977, pp. 369–85, 445–55, 463; Shaybi 1991; Nasr 1970). On the absorption of Shiʿi elements into Sufism during the post-Mongol period, see (Bausani 1968, pp. 538–49). For Sufi influences on the Alawite tradition specifically, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 53–55). |

| 28 | On Alawite gnostic dualism and the concept of docetic divine manifestation, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 72–88; Olsson 1996, esp. 177–79; Erdoğdu-Başaran 2021a, esp. 955–58). |

| 29 | Given the relative paucity of Alevi–Bektashi literature that systematically articulates doctrinal positions, most studies on Alevi theology necessarily rely on poetic, hagiographic, and oral sources. For discussions of the doctrine of the Unity of Being (vahdet-i vücûd) within the Alevi–Bektashi tradition and its monistic conception of the divine primarily grounded in the poetic corpus, see (Karamustafa 2016, pp. 608–9; Oktay 2020, esp. 440; Çift 2009; Eyüboğlu 1990, pp. 213–54, 288–95). For a rare prose exposition of the Alevi–Bektashi understanding of vahdet-i vücûd from an internal perspective, see (Rexheb 2016, pp. 147–50). While some scholars, most notably Ahmet Yaşar Ocak, have argued that Alevi–Bektashi cosmology is more accurately described as a doctrine of wahdat al-mawjūd (unity of the existent) rather than wahdat al-wujūd (unity of being), and, therefore, is closer to a form of materialist polytheism than to Sufi theosophy, this interpretation appears both conceptually and historically problematic; see (Ocak 1998, esp. 122, 129, 135, 259). The term wahdat al-mawjūd is not known to have originated as a self-ascribed theological category within any established mystical or doctrinal tradition. Rather, its usage appears to function primarily as a polemical construct, employed either to accuse certain mystics or groups of collapsing the distinction between Creator and creation (thereby undermining the doctrine of tawḥīd), or by some Sufi thinkers to distance themselves from perceived heretical formulations through an artificial contrast. Functionally, then, the term operates as a rhetorical straw man, used either to caricature so-called “heterodox” cosmologies or to create a foil against which wahdat al-wujūd is framed as “orthodox”. |

| 30 | The notion of Hakk’la Hak olmak is one of the most frequently cited ideas among Alevis, both in everyday religious conversation and in recent popular publications, highlighting its fundamental role in Alevi teachings and self-perception. See (Korkmaz 2003, pp. 184–86; Birdoğan 2003, pp. 275–80). See also (Rexheb 2016, pp. 141–47; Eyüboğlu 1990, pp. 213–28, 239–43, 246–47, 250–53). |

| 31 | For a discussion of the concept of ḥulūl, see (Ay 2015, pp. 1–24). |

| 32 | On Hallaj’s high standing in the Alevi tradition, see (Andersen 2024, pp. 207–31; Rexheb 2016, pp. 43–48). |

| 33 | For discussion of the Alawites’ rejection of mystical union with the divine, particularly in contrast to figures like Hallaj, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 54, 62; Erdoğdu-Başaran 2021a, pp. 955–58). |

| 34 | For details of the Alawite cosmology, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 24, 72–95; Erdoğdu-Başaran 2021a, pp. 956, 958–62; Bar-Asher and Kofsky 2002, pp. 33–35). |

| 35 | For the Alevi–Bektashi understanding of ʿAli and the trinity of Hakk-Muhammad-ʿAli, see (Baba Rexheb 2016, pp. 107–9; Birge [1937] 1994, pp. 132–40; Erdoğdu-Başaran 2021b, pp. 1217–37, esp. 1126–233; Keskin 2017, pp. 121–47). |

| 36 | Bar-Asher and Kofsky (2002, pp. 7–41). Similarly, in an earlier Alawite theological treatise from the tenth century by Muhammad ibn ʿAli al-Jilli, the notion that ʿAli and Muḥammad—or maʿnā and ism—constitute a unity is unequivocally rejected; see (Erdoğdu-Başaran 2021a, 960). |

| 37 | |

| 38 | For the concept of devir, see (Birge [1937] 1994, The Bektashi Order, pp. 120–25). For details and samples of poetry based on this notion, known as devriye, see (Gölpınarlı 1992, pp. 70–82). For a brief discussion of the difference between reincarnation (Ar. tanāsukh) and devir, see (Aşkar 2000, pp. 85–100, see esp. 99–100). For the general Alevi understanding of death and afterlife, also see (Doğan 2022). |

| 39 | On the Alawite understanding of reincarnation, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 105–10; Bar-Asher and Kofsky 2002, pp. 62–66). |

| 40 | For motifs of reincarnation in the Alevi–Bektashi tradition, see (Gölpınarlı 1977, pp. 93–95; Birge [1937] 1994, pp. 129–31). |

| 41 | For a contemporary Alawite exposition of the doctrine of reincarnation, see (Eskiocak 2000). For a medieval articulation of the same belief within an Alawite treatise, see (Bar-Asher and Kofsky 2002, p. 64). |

| 42 | On the saintly figure of Hızır/Hıdır in the Alevi and Alawite traditions, respectively, see (Çınar 2020, pp. 63–74; Türk 2010, pp. 225–42). Also see (Kreinath 2014, pp. 25–66). |

| 43 | (Friedman 2010, pp. 16–42, 93). For a chronological list of medieval Alawite doctrinal texts, see Appendices 1 and 2 in the same volume. |

| 44 | For a basic overview of the Alevi–Bektashi hagiographies and their content, see (Şahin 2020, pp. 87–102). |

| 45 | Some of the most important published collections of Alevi–Bektaşi mystical poetry include Gölpınarlı (1992), Arslanoğlu (1992), Koca (1990), Ergun (1944), and Gölpınarlı and Boratav (1943). For samples of Alevi poetry in English translation, see (Koerbin 2011). Although poetic forms are not entirely absent in the Alawite tradition either, they do not appear to occupy as central or formative a position in its literary and theological culture as they do in Alevism. |

| 46 | See note 19. |

| 47 | |

| 48 | This appears to be the case at least within the Haydari branch of the Alawites, though possibly not in the Kalazi branch. |

| 49 | For a basic comparison of religious organization in the two traditions, see (Türk 2012), the section titled “Dini Lider”. For the Alawites’ initiation and instruction process, also see (Friedman 2010, pp. 210–22; Yıldız 2018, pp. 1–12). |

| 50 | Alevis have faced charges of sexual immorality from hostile outsiders due to their gender-mixed communal rituals; see Imre Adorján, who discusses this in (Adorján 2004, pp. 123–36). Such accusations, including those concerning the practice of orgies, are among the most common and crude strategies of othering, especially when employed against religious minorities. For examples of similar charges of sexual immorality in different historical and religious contexts, see (Grant 1997, pp. 161–70; Shek 2010, pp. 13–51, esp. 41). |

| 51 | On women in the Alawite tradition, see (Çelikdemir and Över 2017, pp. 611–48). On women in the Alevi tradition, see (Karakaya-Stump 2018, pp. 31–43), as well as other relevant articles in the same volume. |

| 52 | There is a substantial body of both popular and scholarly literature on Alevi ritual practices, particularly the communal ritual of the cem and its various components, including music and semah. For example, see (Yaman 1998; Markoff 1993, pp. 95–110; Güray 2019, pp. 97–117; Attepe 2017). There are also a few published historical texts of Bektashi origin—known as erkânnâme—that describe the cem ritual in detail; one example is (Seyfeddin 2007). |

| 53 | On the Alevi cultural revival and the increasing public visibility of Alevism, see (Şahin 2005, pp. 465–85). |

| 54 | For Alawite ritual practices, existing scholarship primarily relies on a book by Sulaiman al-Adhani (b. 1834), a Nusayri renegade who converted first to Christianity and then to Judaism. His book, Kitāb al-Bakūrat fī Kasf Asrār al-Dīyānāt al-Nusayriyah, was published in Beirut in 1863. However, Alawites dispute the accuracy of this source; it should, therefore, be used with great caution, particularly given the author’s pronounced hostility toward the Alawite tradition he ultimately abandoned. |

| 55 | On Muharram fast in Alevi tradition, see (Yaman 2011, pp. 216–20). |

| 56 | (Friedman 2010, pp. 152–73). Mihrājān is celebrated in late October according to the Gregorian calendar and in mid-October according to the Julian calendar. For this reason, it is colloquially referred to as the Festival of Mid-October. |

| 57 | In recent years, growing familiarity with, and rapprochement toward, the Alawite community in Turkey has been accompanied by a modest yet noteworthy trend among Alevis of publicly acknowledging the event of Ghadir Khumm, particularly via social media platforms. Nevertheless, such expressions remain limited in scope and fall short of reflecting the theological centrality and richly elaborated ritual observances that characterize the commemoration of Ghadir Khumm within the Alawite tradition. |

| 58 | For the emotive and moral significance of the Muharram fast for the Alevis, see (Godzińska 2009, pp. 229–33). |

| 59 | For the Alawites’ docetic interpretation of Husayn’s martyrdom in Karbala, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 126–27, 158–9). |

| 60 | For Ibn Taymiyya’s fatwas and their impact, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 187–97; Talhamy 2010, pp. 175–94). For their broader context, also see (Irwin 1986, pp. 95–98). |

| 61 | For these and other oppressive Mamluk policies against the Alawites, see (Friedman 2010, pp. 56–62; Irwin 1986, pp. 110–2). See also (Winter 2016, pp. 61–72). |

| 62 | (Winter 2016, p. 67). Also see (Friedman 2010, pp. 62–63). For the persistent condition of the Alawites as “exceptionally poor”, see (Olsson 1996, pp. 167–68). |

| 63 | Nuh al-Hanafi appears to be a real historical figure, even though he is not mentioned in the standard biographical sources. There is, however, a certain Nuh Çelebi who reportedly served as the chief financial officer (defterdar) of Damascus following the Ottoman conquest of the region in 1516, though it remains unclear whether the two were in fact the same person; see (Tansel 1969, p. 205). On Imadi and his works, see (Köse 1988). The collection of Imadi’s fatwas was later abridged by Muhammad Amin IbnʿAbidin (d. 1836); this abridgment is the version available today: (IbnʿAbidin 1883). Nuh al-Hanafi’s fatwa in question appears on pp. 102–3. See also (Talhamy 2010, pp. 175–94, esp. 181–82); however, Talhamy neither provides a complete citation nor a specific page number for the fatwa. Note should also be made of other narrative sources from the early period of Ottoman rule in Syria, in which various so-called “heterodox” communities are strongly condemned. One example is the extremely negative portrayal of the Druze and the Nusayris/Alawites in the writings of Ibn Tulun al-Dimashqi (d. 1546), one of the best-known chroniclers of the Mamluk–Ottoman transition in and around Damascus; see (Nissim 2016, pp. 1–24, esp. 17–18). According to Nissim, Ibn Tulun “expressed the spirit of contemporary ʿulamāʾ and serves as a mouthpiece for many of them, since many wrote only sporadic treatises”, and “in many cases, these works did not survive and at best we know their names only”. This type of contextual evidence lends further credence to the likelihood of similar direct or explicit official condemnations of the Alawites—texts that may not have survived—and supports the plausibility of a period of persecution preserved in Alawite collective memory and affirmed by Alawite historians; for the latter, see most notably (al-Tawil 1924, pp. 331–36). |

| 64 | Concerning the fiscal discrimination against the Alawites under Ottoman rule, see (Douwes 2000, pp. 142–3; Winter 2016, pp. 70–71, 83–111). |

| 65 | See (Karakaya-Stump 2019, pp. 275–89). For the full text of Hamza Efendi’s fatwa, see also (Tansel 1969, 35n). |

| 66 | Regarding the persecution of the Kizilbash/Alevis and the broader social impact of the fatwas that sanctioned it, see (Karakaya-Stump 2019, pp. 277–81). |

| 67 | For nineteenth-century Ottoman centralization and its impact on the Syrian provinces in general—and the Alawite community in particular—see (Douwes 2000, pp. 153–210; Alkan 2012; Winter 2016, pp. 161–217). For Ottoman policies toward the Alevis and other non-conformist religious communities in Anatolia, and the impact of missionary activity on them, see (Deringil 1998; Karakaya-Stump 2002, pp. 301–24). |

| 68 | For details of the Ottoman state’s coercive measures and military operations against non-Sunni minorities in the 19th century, see (Deringil 1998, Chapter 3; Akçin Somel 1999/2000, pp. 178–201; Akpınar 2015, pp. 215–25). |

| 69 | For instances of local Sunni resistance to the conversion of Alawites to Sunnism, see (Ürkmez and Efe 2010, pp. 127–34). |

| 70 | For instances of Sunni resistance to the inclusion of Alawites in local administrative councils, see (Winter 2016, pp. 209–11). |

| 71 | Ibid., especially the Introduction and Conclusion, as well as pp. 57, 60, 68, 73, and 117. For broader claims regarding Ottoman tolerance toward religious minorities and political pragmatism, see (Barkey 2008; Karpat and Yıldırım 2010; Adanır 2003, pp. 54–66). These works, however, appear prone to a kind of optical illusion in their overall portrayal of the Ottoman politics of difference, largely due to their emphasis on the empire’s non-Muslim subjects at the expense of dissenting Muslim groups such as the Alevis and Alawites. Unlike Jews and Christians—whose incorporation into the Ottoman polity was facilitated by provisions of Islamic law granting them a protected, albeit subordinate, status as “people of the book”—the Alevis and the Alawites lacked any formal legal protection and were classified as apostates subject to capital punishment under Sunni jurisprudence. Another troubling feature of these studies is their tendency to favor pragmatism as the primary explanatory framework for Ottoman policy. By replacing religious fervor with political pragmatism as the presumed timeless operating principle of Ottoman governance, they risk substituting one form of essentialism for another and reinforcing a false binary between religious and political domains. For a broader critique of the increasingly popular use of “pragmatism” as an explanatory category in Ottoman historiography, see (Dağlı 2013, pp. 194–213; Karakaya-Stump 2019, Chapter 6). |

| 72 | (Goldsmith 2015, pp. 141–58, esp. 142–50; Wieland 2015, pp. 225–43; Zırh 2013, pp. 69–76; Eran 2015, pp. 43–57). Needless to say, Alevi and Alawite long-standing political affiliations, especially with the left, are not merely strategic or circumstantial, but are also deeply rooted in affective experiences such as grief over historical persecution, pride in narratives of resistance, and aspirations for a more egalitarian future. These emotions form a powerful affective framework that resonates with the ideals of leftist movements. |

| 73 | Regarding the Alevis’ and Alawites’ continued marginalization under the Turkish Republic, see (Lord 2018, Chapters 1–5; Açikel and Ateş 2011, pp. 713–33; Dressler 2015, 445–51; Bora 2015, pp. 180–7). |

| 74 | For the intensification of Sunnification and sectarian policies under AKP rule, see (Lord 2018, Chapters 5–6; Sandal 2019, 473–91, esp. 6–12; Karakaya-Stump 2017, pp. 53, 67; Karakaya-Stump 2022). |

| 75 | (Karakaya-Stump 2014). Originally published in Turkish: “Gezi’yi Alevileştirmek,” Birdirbir, 18 March 2014. |

| 76 | Concerning overt and veiled sectarian attacks against Kılıçdaroğlu, see (Duvar English 2023; Köker 2023; Akkaya 2022). Also see (Karakaya-Stump 2025). |

| 77 | Regarding the position of Alawites during the French Mandate and Baʿath rule, see (Cleveland and Bunton 2013, pp. 202–8; Farouk-Alli 2015, pp. 27–45, esp. 33–42; Khalaf 1991, pp. 63–70; Fildis 2012, pp. 148–56). |

| 78 | Concerning the continued religious marginalization of the Alawites under Baʿath rule, see (Landis 2003). |

| 79 | On Sunni/Islamist opposition to the Assads’ rule (Cleveland and Bunton 2013, pp. 415–20; Kerr 2015, pp. 1–23, esp. 3–15; Goldsmith 2015, pp. 142–50; Taştekin 2015, pp. 25–32). |

| 80 | For a discussion of the armed Islamist insurgency of the late 1970s and early 1980s and its aftermath, see (Cleveland and Bunton 2013, pp. 422–4; Taştekin 2015, pp. 32–45; Kerr 2015, pp. 16–17). |

| 81 | On the sectarian nature of the Syrian Civil War, see (Taştekin 2015, pp. 45–109; Goldsmith 2015, pp. 154–7; Wieland 2015, pp. 225–43). |

| 82 | For a rare glimpse into the Alawites’ perspective on the Civil War, see (Glass 2014). |

| 83 | For examples of early reports concerning sectarian violence against the Alawites following the fall of Bashar al-Assad, see (Syrian Observatory for Human Rights 2025; Syrian Network for Human Rights 2025; Lemkin Institute for Genocide Prevention 2025; Christian Solidarity International 2025). |

| 84 | For a representative report on Turkey’s facilitation of jihadists’ crossings into Syria during the Syrian Civil War, see (Pamuk and Tattersall 2015). |

| 85 | For a representative report on such incidents, see (Cumhuriyet 2015). |

| 86 | For sample reports on the building of refugee settlements in Alevi-dense regions, see (Dağlar 2016; OdaTV 2016). |

| 87 | For discussions of the growing solidarity between Alevis and Alawites in the aftermath of the Syrian Civil War and sectarian violence in Syria, see (Sandal 2019, pp. 9–18; Karakaya-Stump 2017, pp. 11–12). |

References

- Açikel, Fethi, and Kazim Ateş. 2011. Ambivalent Citizen: The Alevi as the ‘Authentic Self’ and the ‘Stigmatized Other’ of Turkish Nationalism. European Societies 13: 713–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adanır, Fikret. 2003. Religious Communities and Ethnic Groups Under Imperial Sway: Ottoman and Habsburg Lands in Comparison. In The Historical Practice of Diversity: Transcultural Interactions from the Early Mediterranean to the Postcolonial World. Edited by Dirk Hoerder, Christiane Harzig and Adrian Shubert. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Adorján, Imre. 2004. ‘Mum Söndürme’ İftirasının Kökeni ve Tarihsel Süreçte Gelişimiyle İlgili Bir Değerlendirme. In Alevilik. Edited by İsmail Engin and Havva Engin. Istanbul: Kitap Yayınevi, pp. 123–36. [Google Scholar]

- Akçin Somel, Selçuk. 1999/2000. Osmanlı Modernleşme Döneminde Periferik Nüfus Grupları. Toplum ve Bilim 83: 178–201. [Google Scholar]

- Akın, Bülent. 2023. Alevi mi? Kızılbaş mı? Şia mı? ‘Alevi’ Sözcüğünün Tarihte Bugünkü Anlamıyla Kullanımına Dair Birtakım Yeni Mülahazalar. Alevilik-Bektaşilik Araştırmaları Dergisi 28: 18–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, Gülfer. 2022. Alevifobi Kalsın, Alevi Gitsin Diyorsun. May 23. Available online: https://gasteavrupa.org/2022/05/23/alevifobi-kalsin-alevi-gitsin-diyorsun/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Akpınar, Alişan. 2015. II. Abdülhamid Dönemi Devlet Zihniyetinde Alevi Algısı. In Kizilbashlık Alevilik Bektaşilik Tarih-Kimlik-İnanç-Ritüel. Edited by Yalçın Çakmak and İmran Gürtaş. Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, pp. 215–25. [Google Scholar]

- Aktaş, Ali, Hüseyin Bal, Nasuh Barin, İlhan Cem Erseven, Sadık Göksu, Burhan Kocadag, Murat Küçük, İsmail Onarli, Baki Öz, Cemal Şener, and et al., eds. 1998. Ali’siz Alevilik Olur mu? Istanbul: Ant Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Alkan, Necati. 2012. Fighting for the Nuṣayrī Soul: State, Protestant Missionaries and the ‘Alawīs in the Late Ottoman Empire. Die Welt des Islams 52: 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al-Qadi, Wadad. 1976. The Development of the Term Ghulāt in Muslim Literature with Special Reference to Kaysāniyya. In Akten des VII. Kongresses für arabistik und Islamwissenschaft Göttingen. Edited by Albert Dietrich. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 295–319. [Google Scholar]

- al-Tawil, Muhammad Amin Ghalib. 1924. Tārīkh al-ʿAlawiyyīn. Lazkiya: pp. 331–36. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, Angela. 2024. When the Meydan Becomes the Dar: The Martyrdom of Mansur al-Hallaj and the Cem Setting. Journal of Turkish and Ottoman Studies 11: 207–31. [Google Scholar]

- Arslanoğlu, İbrahim. 1992. Şah İsmail Hatayî ve Anadolu Hatayîleri. Istanbul: Der Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Asatryan, Mushegh. 2017. Controversies in Formative Shiʿi Islam: The Ghulāt Muslims and Their Beliefs. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Aşkar, Mustafa. 2000. Reenkarnasyon (Tenasüh) Meselesi ve Mutasavvıfların Bu Konuya Bakışlarının Değerlendirilmesi. Tasavvuf 1: 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Attepe, Arzu. 2017. Alevilerin Cem İbadetine Görsel Bir Bakış. Istanbul: Can Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Ay, Resul. 2015. Erken Dönem Anadolu Sufiliği ve Halk İslam’ında Hulûlcü Yaklaşımlar ve Hulûl Anlayışının Farklı Tezahürleri. Bilig 72: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Asher, Meir M., and Aryeh Kofsky. 2002. The Nuṣayrī-ʿAlawī Religion: An Enquiry into Its Theology and Liturgy. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Barkey, Karen. 2008. Empire of Difference: The Ottomans in Comparative Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barzegar, Abbas. 2011. The Persistence of Heresy: Paul of Tarsus, Ibn Sabaʾ, and Historical Narrative in Sunni Identity Formation. Numen 58: 207–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausani, Alessandro. 1968. Religion in the Post-Mongol Period. In The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods. Edited by John Andrew Boyle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 538–49. [Google Scholar]

- Birdoğan, Nejat. 2003. Anadolu’nun Gizli Kültürü Alevilik, 4th ed. Istanbul: Kaynak Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Birge, John Kingsley. 1994. The Bektashi Order of Dervishes. Reprint. London: Luzac Oriental. First published 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Bora, Tanıl. 2015. Türk Sağı Nazarında Alevi: Üç Fragman. Birikim, 180–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, Faik. 1997. Ali’siz alevilik. Ankara: Doruk. [Google Scholar]

- Christian Solidarity International. 2025. Christian Solidarity International Issues Genocide Warning for Syria. Christian Solidarity International. March 11. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20250311175650/https:/www.csi-int.org/news/christian-solidarity-international-issues-genocide-warning-for-syria/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Cleveland, William L., and Martin Bunton. 2013. A History of the Modern Middle East, 5th ed. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cumhuriyet. 2015. Alevilerin Evleri Yine Işaretlendi. Cumhuriyet, June 28. Available online: http://www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/haber/turkiye/308903/Aleilerin_evleri_yine_isaretlendi.html (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Çamuroğlu, Reha. 1998. Alevi Revivalism in Turkey. In Alevi Identity: Cultural, Religious and Social Perspectives. Edited by Tord Olsson, Elisabeth Özdalga and Catharina Raudvere. Istanbul: Isis Press, pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Çelikdemir, Murat, and Gökben Över. 2017. Nusayrilikte Kadın. In Doç. Dr. Durak Aksoy Anısında: Hayatı, Eserleri ve Armağanı. Gaziantep: Gaziantep Üniversitesi, pp. 611–48. [Google Scholar]

- Çift, Salih. 2009. Bektâşî Geleneğinde Vahdet-i Vücûd ve İbnü’l-Arabî. Tasavvuf: İbnü’l-Arabî Özel Sayısı-II 9: 257–79. [Google Scholar]

- Çınar, Ali Abbas. 2020. Alevilerde Hızır Kültü ve Ritüelleri. Millî Folklor 16: 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Dağlar, Ali. 2016. Maraş’tan sonra Sivas Divriği: Alevi nüfusu yoğun ilçeye mülteci kampı hazırlığı. Diken, May 12. Available online: https://www.diken.com.tr/marastan-sonra-sivas-divrigi-alevi-nufusu-yogun-ilceye-multeci-kampi-hazirligi/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Dağlı, Murat. 2013. The Limits of Ottoman Pragmatism. History and Theory 52: 194–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deringil, Selim. 1998. The Well-Protected Domains: Ideology and the Legitimation of Power in the Ottoman Empire, 1876–1909. New York: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Doğan (Dede), Binali. 2022. Erkan-ı Evliya. Istanbul: Berdan Marbaacılık. [Google Scholar]

- Douwes, Dick. 2000. The Ottomans in Syria: A History of Justice and Oppression. London and New York: I.B. Tauris Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Dönmez, Mehmet. 2004. Alevilik ve Tasavvuf. In Alevilik. Edited by İsmail Engin and Havva Engin. Istanbul: Kitap Yayinevi, pp. 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, Markus. 2015. Turkish Politics of Doxa: Otherizing the Alevis as Heterodox. Philosophy and Social Criticism 41: 445–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvar English. 2023. Struggling with Kılıçdaroğlu’s ‘Alevi’ Declaration, Erdoğan Tells Him to Conceal Identity, Live It Privately. May 1. Available online: https://www.duvarenglish.com/struggling-with-kilicdaroglus-alevi-declaration-erdogan-tells-him-to-conceal-identity-live-it-privately-news-62315 (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Eran, Mehmet. 2015. Örtük politikleşmeden kimlik siyasetine: Aleviliğin Politikleşmesi ve Sosyalist Sol. Birikim, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Erdoğdu-Başaran, Reyhan. 2021a. Er-Risâletü’l-Numâniyye Eseri Doğrultusunda Nusayrî-Alevî İnancında Tevhîd İlkesinin İzahı. Mezhep Araştırmaları Dergisi 14: 948–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğdu-Başaran, Reyhan. 2021b. Yazılı Alevi Metinlerinde Allah Tasavvuru. Pamukkale Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 8: 1217–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun, Sadeddin Nüzhet. 1944. Bektaşi edebiyati antolojisi: Bektaşi şairleri ve nefesleri. Istanbul: Maarif Kitaphanesi. [Google Scholar]

- Eskiocak, Nasreddin. 2000. Yaratıcının azameti ve kur’ân’daki reenkarnasyon. Istanbul: Can Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Eyüboğlu, Zeki. 1990. Bütün Yönleriyle Bektaşilik. Istanbul: Der Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Farouk-Alli, Aslam. 2015. The Genesis of Syria’s Alawi Community. In The Alawis of Syria: War, Faith and Politics in the Levant. Edited by Michael Kerr and Craig Larkin. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Federation of Alawites in Europe. 2024. Statement to the Public by the Federation of Alawites in Europe. Ehlen Dergisi, December 26. Available online: https://ehlendergisi.com/index.php/2024/12/26/statement-to-the-public-by-the-federation-of-alawites-in-europe/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Fildis, Ayşe Tekdal. 2012. Roots of Alawite-Sunni Rivalry in Syria. Middle East Policy 19: 148–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Yaron. 2010. The Nuṣayrī-ʿAlawīs: An Introduction to the Religion, History, and Identity of the Leading Minority in Syria. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, Charles. 2014. In the Syria We Don’t Know. The New York Review, November 6. Available online: https://www-nybooks-com.us1.proxy.openathens.net/articles/2014/11/06/syria-we-dont-know/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Godzińska, Marzena. 2009. Ritualized Emotions: Muharrem Mourning in Alevi and Bektashi Groups in Turkey. In Codes and Rituals of Emotions in Asia and African Cultures. Edited by Nina Pawlak. Warsaw: Elipsa, pp. 229–33. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, Leon T. 2015. Alawi Diversity and Solidarity: From the Coast to the Interiors. In The Alawis of Syria: War, Faith and Politics in the Levant. Edited by Michael Kerr. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 141–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gölpınarlı, Abdülbâkî. 1977. Tasavvufʾtan dilimize geçen deyimler ve atasözleri. Istanbul: İnkılâp ve Aka Kitabevleri. [Google Scholar]

- Gölpınarlı, Abdülbâkî. 1992. Alevî bektaşî nefesleri. Istanbul: İnkılâp Kitabevi. [Google Scholar]

- Gölpınarlı, Abdülbâkî, and Pertev Nailî Boratav. 1943. Pir Sultan Abdal. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Robert M. 1997. Charges of Immorality against Religious Groups in Antiquity. In Studies in Gnosticism and Hellenistic Religions: Studies Presented to Gilles Quispel on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Edited by R. van den Broek and M. J. Vermaseren. Leiden: Brill, pp. 161–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gülten, Sadullah. 2016. Osmanlı Devleti’nde Alevî Sözcüğünün Kullanımına Dair Bazı Değerlendirmeler. Alevilik Araştırmaları Dergisi 11: 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gümüş, Burak. 2007. Die Wiederkehr des Alevitentums in der Türkei und in Deutschland. Konstanz: Hartung-Gorre Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Güray, Cenk. 2019. Çubuk ve Şabanözü Bölgeleri Alevi Köylerindeki Cem Geleneklerine Müzik Açısından Bir Bakış. Türk Kültürü ve Hacı Bektaş Veli Araştırma Dergisi 89: 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Halm, Heinz. 1960. Nuṣayriyya. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, Marshall G. S. 1955. How Did the Early Shiʿa Become Sectarian? Journal of the American Oriental Society 75: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, Marshall G. S. 1977. The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- IbnʿAbidin, Muhammad Amin. 1883. 1300 AH/1883 CE. Al-ʿUqūd al-durriyyah fī tanqīḥ al-fatāwā al-Ḥāmidiyyah. Cairo: al-Maṭbaʿah al-ʿĀmirah al-Mīriyyah. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, Robert. 1986. The Middle East in the Middle Ages: The Early Mamluk Sultanate 1250–1382. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya-Stump, Ayfer. 2002. Alevilik Hakkında 19. Yüzyıl Misyoner Kayıtlarına Eleştirel Bir Bakış ve Ali Gako’nun Öyküsü. Folklor/Edebiyat 29: 301–24. [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya-Stump, Ayfer. 2014. Alevizing Gezi. Jadaliyya. March 26. Available online: http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/17087/alevizing-gezi (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Karakaya-Stump, Ayfer. 2017. The AKP, Sectarianism, and the Alevis’ Struggle for Equal Rights in Turkey. National Identities 18: 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya-Stump, Ayfer. 2018. Kadın ve Toplumsal Cinsiyet Çalışmaları Perspektifinden Alevi-Bektaşi Tarihi ve Tarih Yazıcılığı: Bazı Ön Değerlendirmeler. In Hakikatin Darına Durmak: Alevilikte Kadın. Edited by Bedriye Poyraz. Istanbul: Dipnot Yayınları, pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya-Stump, Ayfer. 2020. The Kizilbash-Alevis in Ottoman Anatolia: Sufism, Politics, and Community. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya-Stump, Ayfer. 2022. Cemevlerini Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı’na Bağlama Girişimi: Aleviliği Devletleştirme Hamlesi. 1+1 Express, November 23. Available online: https://birartibir.org/aleviligi-devletlestirme-hamlesi/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Karakaya-Stump, Ayfer. 2025. Mezhepçiliğin Gündelik Hâlleri ve Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu Vakası. Alevilerin Sesi. Available online: https://alevilerinsesi.eu/doc-dr-ayfer-karakaya-stump-mezhepciligin-gundelik-halleri-ve-kemal-kilicdaroglu-vakasi/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Karamustafa, Ahmet T. 1994. God’s Unruly Friends: Dervish Groups in the Islamic Later Middle Period, 1200–1550. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karamustafa, Ahmet T. 2016. In His Own Voice: What Hatayi Tells Us about Şah İsmail’s Religious Views. In L’ésotérisme Shiʿite: Ses racines et ses prolongements/Shiʿi Esotericism: Its Roots and Developments. Edited by Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Karpat, Kemal, and Yetkin Yıldırım, eds. 2010. The Ottoman Mosaic. Seattle: Cune Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kazimi, Nibras. 2010. Syria Through Jihadist Eyes: A Perfect Enemy. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kehl-Bodrogi, Krisztina. 1993. Die ‘Wiederfindung’ des Alevitums in der Türkei: Geschichtsmythos und kollektive Identität. Orient 34: 267–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kehl-Bodrogi, Krisztina, Barbara Kellner-Heinkele, and Anke Otter-Beaujean, eds. 1997. Syncretistic Religious Communities in the Near East: Collected Papers of the International Symposium ‘Alevism in Turkey and Comparable Syncretistic Religious Communities in the Near East in the Past and Present’. Leiden and New York: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, Michael, ed. 2015. Introduction: For ‘God, Syria, Bashar and Nothing Else’? In The Alawis of Syria: War, Faith and Politics in the Levant. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Keskin, Ahmet. 2017. Hakk-Muhammed-Ali Dedim: Şah Hatâyî Şiirinde Estetik Bir Dinamik Olarak Niyaz ve Kaynakları. Alevilik-Bektaşilik Araştırmaları Dergisi, 121–47. [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf, Sulayman N. 1991. Land Reform and Class Structure in Rural Syria. In Syria: Society, Culture, and Polity. Edited by Richard T. Antoun and Donald Quataert. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Koca, Turgut, ed. 1990. Bektaşi Alevi Şairleri ve Nefesleri. Istanbul: Maarif Kitaphanesi. [Google Scholar]

- Koerbin, Paul V. 2011. ‘I Am Pir Sultan Abdal’: A Hermeneutical Study of the Self-Naming Tradition (Mahlas) in Turkish Alevi Lyric Song (Deyiş). Ph.D. dissertation, University of Western Sydney, Penrith, NSW, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz, Esat. 2003. Ansiklopedik alevilik-bektaşilik terimleri sözlüğü, 3rd ed. Istanbul: Kaynak Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Köker, Levent. 2023. Kılıçdaroğlu’nun Alevîlik hamlesi ve ‘kimlik siyaseti’. Medyascope, April 22. Available online: https://medyascope.tv/2023/04/22/levent-koker-yazdi-kilicdaroglunun-alevilik-hamlesi-ve-kimlik-siyaseti/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Köse, Saffet. 1988. İmâdî. In Türkiye diyanet vakfı İslâm ansiklopedisi. Istanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı. [Google Scholar]

- Kreinath, Jens. 2014. Virtual Encounters with Hızır and Other Muslim Saints: Dreaming and Healing at Local Pilgrimage Sites in Hatay, Turkey. Anthropology of the Contemporary Middle East and Central Eurasia 2: 25–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, Joshua M. 2003. Islamic Education in Syria: Undoing Secularism. Providence: Watson Institute for International Studies, Brown University. [Google Scholar]

- Lemkin Institute for Genocide Prevention. 2025. Red Flag Alert for Syria: Genocidal Sectarian Violence Against Alawites. March 12. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20250312152048/https:/www.lemkininstitute.com/red-flag-alerts/red-flag-alert-for-syria:-genocidal-sectarian-violence-against-alawites (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Leopold, Anita Maria, and Jeppe Sinding Jensen, eds. 2004. Syncretism in Religion: A Reader. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, Ceren. 2018. Religious Politics in Turkey: From the Birth of the Republic to the AKP. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Markoff, Irene. 1993. Music, Saints, and Ritual: Samāʿ and the Alevis of Turkey. In Manifestations of Sainthood in Islam. Edited by Grace Martin Smith. Istanbul: Isis Press, pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Maroney, Eric. 2006. Religious Syncretism. London: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Massignon, Louis. 1913–1936. Nuṣayrī. In Encyclopaedia of Islam. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Moosa, Matti. 1988. Extremist Shiites: The Ghulat Sects. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. 1970. Shiʿism and Sufism: Their Relationship in Essence and in History. Religious Studies 6: 229–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim, Chaim. 2016. Between Mamluks and Ottomans: The Worldview of Muḥammad Ibn Ṭūlūn. ATINER’s Conference Paper Series TUR2015-2167; Athens: Athens Institute for Education and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Ocak, Ahmet Yaşar. 1998. Osmanlı toplumunda zindiklar ve mülhidler (15.–17. Yüzyıllar). Istanbul: Türk Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- OdaTV. 2016. Konteyner Kentlerde Amaç Alevi Asimilasyonu Mu? April 27. Available online: https://www.odatv.com/guncel/konteyner-kentlerde-amac-alevi-asimilasyonu-mu-93418 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Oktay, Zeynep. 2020. Historicizing Alevism: The Evolution of Abdal and Bektashi Doctrine. Journal of Shiʿa Islamic Studies 13: 425–59. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, Tord. 1996. The Gnosis of Mountaineers and Townspeople: The Religion of the Syrian Alawites, or the Nuṣayrīs. In Alevi Identity. Edited by Tord Olsson, Elisabeth Özdalga and Catharina Raudvere. Istanbul: Swedish Research Institute, pp. 167–83. [Google Scholar]

- Öztoprak, Halil. 1990. Kur’an’da hikmet tarih’te hakikat ve kur’an’da hikmet incil’de hakikat, 4th ed. Istanbul: Can Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Pamuk, Hümeyra, and Nick Tattersall. 2015. Turkish Intelligence Helped Ship Arms to Syrian Islamist Rebel Areas. Reuters, May 21. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/world/exclusive-turkish-intelligence-helped-ship-arms-to-syrian-islamist-rebel-areas-idUSKBN0O61L1/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Rexheb, Baba. 2016. Islamic Mysticism and the Bektashi Path. Chicago: Babagân Books. [Google Scholar]

- Saltık, Veli. 2004. İz birakanlar ve Alevi ocaklari. Ankara: Kuloğlu Matbaacılık. [Google Scholar]

- Sandal, Nükhet A. 2019. Solidarity Theologies and the (Re)definition of Ethnoreligious Identities: The Case of the Alevis of Turkey and Alawites of Syria. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 48: 473–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfeddin, Muhammed ibn Zülfikârî Derviş Ali. 2007. Bektaşi ikrar ayini. Translated by Mahir Ünsal Eriş. Ankara: Kalan Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Shankland, David. 2012. Are the Alevis Shiʿite? In Shiʿi Islam and Identity: Religion, Politics and Change in the Global Muslim Community. Edited by Lloyd Ridgeon. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, pp. 210–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Rosalind, and Charles Stewart, eds. 1994. Syncretism/Anti-Syncretism: The Politics of Religious Synthesis. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shaybi, Mustafa Kamil. 1991. Sufism and Shiʿism. Surrey: LAAM. [Google Scholar]

- Shek, Richard. 2010. The Alternative Moral Universe of Religious Dissenters in Ming-Qing China. In Religion and the Early Modern State: Views from China, Russia, and the West. Reissue ed. Edited by James D. Tracy and Marguerite Ragnow. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 13–51. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Devin J. 1998. Islamic Legal Orthodoxy: Twelver Shiite Responses to the Sunni Legal System. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov, Yuri. 2010. Early and Recent Formulations of Theories for a Formative Christian Heterodox Impact on Alevism. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 37: 261–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, Jonas. 2012. Bektaşi Demiş: Orthodox Sunni, Heterodox Bektasian Incongruity in Bektasi Fikralari. Master’s dissertation, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Syrian Network for Human Rights. 2025. Daily Update: Extrajudicial Killings in the Wake of Events in the Coastal Region from March 6 to March 17. March 17. Available online: https://archive.md/20250317165402/https:/news.snhr.org/2025/03/17/daily-update-extrajudicial-killings-in-the-wake-of-events-in-the-coastal-region-from-march-6-to-march-17/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. 2025. Amid Ongoing Massacres and Violations: Thousands of Missing People and Hundreds of Unidentified Bodies Reported in Syrian Coastline. March 22. Available online: https://www.syriahr.com/en/358387/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Şahin, Haşim. 2020. Alevi-Bektaşi Tarihinin Yazılı Kaynakları: Velâyetnâmeler. Türkiye Araştırmaları Literatür Dergisi 16: 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, Şehriban. 2005. The Rise of Alevism as a Public Religion. Current Sociology 53: 465–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhamy, Yvette. 2010. The Fatwas and the Nusayri/Alawīs of Syria. Middle Eastern Studies 46: 175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansel, Selahattin. 1969. Yavuz Sultan Selim. Ankara: Milli Eğitim Basımevi. [Google Scholar]

- Taştekin, Fehim. 2015. Alacakaranlıkta ortadoğu: Suriye: Yıkıl git, diren kal! Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, William F. 2014. The Kūfan Ghulāt and Millenarian (Mahdist) Movements in Mongol-Türkmen Iran. In Unity in Diversity: Mysticism, Messianism and the Construction of Religious Authority in Islam. Edited by Orkhan Mir-Kasimov. Leiden: Brill, pp. 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Türk, Hüseyin. 2010. Nusayrîlerde Hızır İnancı. Türk Kültürü ve Hacı Bektaş Veli Araştırma Dergisi 54: 225–42. [Google Scholar]

- Türk, Hüseyin. 2012. Arap Aleviliği ile Anadolu Aleviliğinin Benzer ve Farklı Yönleri. In II. Uluslararası tarihten bugüne alevîlik sempozyumu (23–24 Ekim 2010). Edited by Aykan Erdemir, Mehmet Ersal, Ahmet Taşğin and Ali Yaman. Ankara: Cem Vakfı Ankara Şubesi. [Google Scholar]

- Ürkmez, Naim, and Aydın Efe. 2010. Osmanlı Arşiv Belgelerinde Nusayrîler Hakkında Genel Bilgiler. Türk Kültürü ve Hacı Bektaş Veli Araştırma Dergisi 54: 127–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wieland, Carsten. 2015. Alawis in the Syrian Opposition. In The Alawis of Syria: War, Faith and Politics in the Levant. Edited by Michael Kerr. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 225–43. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Stefan. 2016. A History of the ‘Alawis: From Medieval Aleppo to the Turkish Republic. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yaman, Mehmet. 1998. Alevîlikte cem. Istanbul. [Google Scholar]

- Yaman, Mehmet. 2011. Alevîlik: İnanç, edeb, erkân. Istanbul: Demos Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, Harun. 2018. Nusayrîler Arap Alevîleri’nde Amcalık Kurumu. Alevilik Araştırmaları Dergisi 8: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zırh, Besim Can. 2013. CHP, Aleviler ve Stockholm Sendromu. Birikim 287: 69–76. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karakaya-Stump, A. Alevis and Alawites: A Comparative Study of History, Theology, and Politics. Religions 2025, 16, 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081009

Karakaya-Stump A. Alevis and Alawites: A Comparative Study of History, Theology, and Politics. Religions. 2025; 16(8):1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081009

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarakaya-Stump, Ayfer. 2025. "Alevis and Alawites: A Comparative Study of History, Theology, and Politics" Religions 16, no. 8: 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081009

APA StyleKarakaya-Stump, A. (2025). Alevis and Alawites: A Comparative Study of History, Theology, and Politics. Religions, 16(8), 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081009